Stuart Harrison's Blog, page 2

March 30, 2014

The Flyer Sequel Update

I was hoping to include the cover art for the sequel to The Flyer in this post, but it hasn’t arrived yet, though the designer is working on it. The editor has returned the manuscript, and I’ll finish going through it this week, then it will go to the formatter. Publish date looks like being the third week of April. The book is called : We Should Dance, which is a change from the working title of The Mayfly Season. Both refer to the fact that life is short and sometimes difficult, therefore it should be lived to the full. (Life isn’t always a party, but we should dance anyway).

though the designer is working on it. The editor has returned the manuscript, and I’ll finish going through it this week, then it will go to the formatter. Publish date looks like being the third week of April. The book is called : We Should Dance, which is a change from the working title of The Mayfly Season. Both refer to the fact that life is short and sometimes difficult, therefore it should be lived to the full. (Life isn’t always a party, but we should dance anyway).

In other news, last week I rewrote the blog posts about my journey to becoming an author, adding the final instalments to conclude the story, though they are not on my website. Sometime in April I will make the entire narrative available as a FREE ebook available at Amazon, Kobo etc. I’ll post here when it’s published. I just need to get it edited and have the artwork done.

Right now, I’m about to start work on the third instalment of the Pitsford Series (which is the name I’ve given the series beginning with The Flyer). Publication of number three is planned for late May.

Finally for now, one of the four books I published after The Snow Falcon has appeared as an ebook on Amazon. I wasn’t aware that it was happening, as the rights holder, Harper Collins, didn’t communicate with me, which is a bit strange. Anyway, the book is Lost Summer, and is available from Amazon and Kobo.

March 12, 2014

The Flyer Sequel

Time for an update on progress of the sequel to The Flyer. I’m happy to say that the  book is very nearly finished, by which I mean I have two chapters to write, neither of which are very long. It’s possible I could cross the line tomorrow, or maybe the day after and since there’s a cyclone expected here at the weekend I may as well work. Providing the house doesn’t get blown away of course. Fingers crossed.

book is very nearly finished, by which I mean I have two chapters to write, neither of which are very long. It’s possible I could cross the line tomorrow, or maybe the day after and since there’s a cyclone expected here at the weekend I may as well work. Providing the house doesn’t get blown away of course. Fingers crossed.

I thought I’d give a few teasers about what the book is about. I say ‘the book’ because though I’ve had a working title from the start I’m not sure If I’ll stick with it. I have a few others ideas scribbled on post-its around my desk. Once I do figure it out I can brief a cover designer. From brief to completion can take a couple of weeks so I need to get on to that to stay on schedule for my April release date. That means the kind people who offered to read the manuscript can expect it to arrive in their inbox very soon. As I’ll be busy rewriting and editing while you read, I’m afraid what you’re going to get is the hot-off-the-keyboard absolutely uncorrected version which will be rife with spelling errors, missed words, occasional inconsistencies in narrative and other cock-ups. Sorry about that. I’m looking for any kind of actual story feedback at all, but primarily I just want to know if you like what you read, and especially whatever you can tell me about any bits you didn’t like.

So, back to what the story is actually about. It takes up pretty much where The Flyer ended, with William and Elizabeth returning to England after their meeting in France in 1920. They reunite with Christopher who’s recovering at Pitsford from his self-inflicted war wounds. As William and Elizabeth prepare to announce their engagement an event that I won’t reveal here makes it important to know what William has been doing since the end of the war. At this point the story switches to America and is related from the point-of-view of a new character. Her name is Mona Curtiss and she is a seventeen year old country girl from a poor Illinois farming family. She dreams of escaping her life to go to California where the fledgling silent movie industry has produced stars like Mona’s favourite, Mary Pickford. One Sunday as Mona chafes against the restrictions of her small-town life, and having avoided going to church with the rest of her family, she is sitting in the shade of the porch of her home when she hears an unfamiliar sound. She goes out to the field and shielding her eyes against the sun she sees the first real airplane of her life. It is flying so low that she can see the pilot in the cockpit, looking down at her as she looks up. She waves and to her surprise the biplane comes back and lands in the field and once the noisy engine has stopped the young pilot climbs down to the ground and flashes her a grin. He flicks out a cigarette and tells her his name is Nick and he is with the flying show coming to town. As far as Mona is concerned he’s just about the most exciting thing that has happened in her young life, and he’s good-looking too.

This book alternates between England and America and follows the fortunes of both the original characters and some colourful new ones. In America the story begins in Illinois and the northern states where William and Nick have teamed up to become barnstormers performing air-shows in front of the populations of small towns. It moves on to Florida and eventually New Mexico and California where Mona gets her introduction to the picture business. Amid the daring and the glamour there are tangled love affairs, jealousies and rivalries that sometimes lead to violence and tragedy, and through it all, Elizabeth and William struggle with the powerful feelings they have for one another while fate seems determined to keep them apart.

I think that gives a little flavour of the kind of story it is. Like The Flyer it is essentially a love story, but I think it’s fair to say the sequel is faster-paced and has a few more twists and turns along with some quite different settings. I’ve enjoyed writing it and I’m slightly surprised that I managed to stick to my schedule of go-to-whoa in five weeks without (I hope) making too many compromises in the quality of either the writing or the story. In fact over the past few days I’ve been considering writing the third part of the series more or less straight away, something I was intending to do later in the year. I’ve become quite interested in early Hollywoodland (as it was known then – it was actually a real estate development originally) and I’d like to write some more about it. I also touched lightly on Oswald Mosley and the rise of the fascist movement in Europe during the 30′s and I think that’s something I’d like to weave into the next episode too. It would feature the next generation of characters, and of course I’ve laid the foundations for all of that already.

Anyway, stay tuned for more information soon. And a title.

February 27, 2014

Sequel to The Flyer to be released in April

I suddenly realised today that it’s the end of the month, and I haven’t posted anything for a while now. The reason is that I’ve been writing at a frenetic pace to produce a sequel to The Flyer. Right now I’m sitting on 80 000 words, which for those not familiar with the idea of measuring book length by words, means I’m about two-thirds done. The interesting thing here is that it’s taken me three weeks to get to this point, and I’ll be finished in another two. After that I’ll edit and rewrite before sending the manuscript to the editor I use in the UK, which means the finished book will be available to buy sometime in April.

It’s worth noting that by contrast I spent two years writing The Flyer, including research. The Snow Falcon took about nine months, not including the thirty-odd years of prior experience that was an essential part of the process, especially the two years immediately prior which I’ve been writing about in my ongoing blog posts. (I intend to sit down and finish that very soon, by the way.) My point though, is that the as yet untitled sequel to The Flyer has been written in what is for me record-breaking time and it doesn’t stop there. Not only will I release the sequel in April as an e-book (though it will be available in print from Amazon as well), but there will be a third instalment of the series later in the year. As well that I intend to release four other full length novels this year. They will form part of a different series that I’ll be writing under a different name. More on that another time. So, during 2014 I’ll be writing and releasing six full length novels, which is more than I wrote in five years beginning with Snow Falcon and ending with Aphrodite’s Smile.

To accomplish this I’m going to have to stick to a very disciplined work regime which includes writing a novel at the rate of five thousand words a day. That’s roughly 12-15 pages of a standard printed paperback. it takes a lot of concentrated effort to maintain that kind of output. It means spending at least six hours a day at the keyboard, working to a reasonably fleshed-out story plan. The plan is essential because working like this I don’t have the luxury of writing three four or five drafts as I normally would. I’ve only got time to do two drafts and if I’m going to keep to schedule I can only spend a couple of weeks on the second draft versus five on the first. I doubt that very many people could keep up that level of working while still producing a decent book at the end of it, and that’s the key issue. Will the work be good enough? I mean, if The Flyer took two years to write and the sequel will take that many months, what does that say about the quality of the writing?

Well, it’s not quite as straight-forward as that. The Flyer was a difficult story to write partly because of the research involved, and much of that research is applicable to the sequel so there’s a time-saving there. I’m also using the same principle characters and a big part of writing any novel is figuring out the characters. It’s a lot easier in some forms of genre fiction such as thrillers where the plot is far more important than the characters whose motivations tend to be simpler and the conflicts they face primarily external rather than partially internal, which is the case with The Flyer, for instance. So there was another time-saving there when I came to writing the sequel. Even with those caveats though, two months is a very short time to write a full length novel and still maintain the quality, which for me has always been the goal. It begs the question though, what is quality anyway? Who judges it? Of course the answer is the reader, and it will be readers who judge whether the sequel measures up.

I am my most rigorous critic as can probably be said about most writers. I’m never really happy with my own work, I always think there’s more I could do to improve a book I’m working on. The danger with being too hard on myself is that it can result in a lack of confidence that means I’m reluctant to release books, and so my output dwindles. On other side of the coin I spent two years of my life writing The Flyer, which I know is a good book, a view confirmed by readers, and yet I haven’t been able to find a publisher for it. The reason for that failure has more to do with the state of the publishing industry than anything else and I don’t intend to go into that here. However it’s fair to say that with e-book technology and online stores such as Amazon, publishing has undergone a huge change and that process will continue. Writers can now publish their own work quite easily and readers are buying it. There has been much talk in the industry about perceived quality, mostly negative talk by publishers who are dismayed to find that they no longer decide what the public wants, and neither do agents or critics, but rather it is the readers themselves. This is the Internet, which has given ordinary people a voice they have never had before. Readers want quality, of course, but they decide what represents quality.

Readers also want content. I’m a reader myself, obviously. I read a lot. When I find an author I like, I want more. When I find characters and fictional ‘worlds’ that I like, whether that means a particular era or setting or background or whatever, I want more of that too. hence the popularity of series’ as opposed to stand-alone novels. This is why I’m continuing the series I started with The Flyer, which I always intended to be at least a trilogy. It’s also why I’ll be writing another series too, (thrillers) and explains why I’m planning to release six books this year.

Am I happy with the quality of the sequel to The Flyer? I’m two-thirds of the way through and the answer is that yes, I am. I hope readers will be too. In my next post I’ll tell you a little bit about the story. In the meantime, I’d love to hear from anyone who would be interested in reading an advance draft (as a word document that I’ll email to you) before the manuscript goes to the editor so that I can get some feedback. In return I’ll send you a print version of the finished novel direct from Amazon when it’s released. Let me know via the contact form. Thanks.

January 25, 2014

The Pursuit of Happiness (Part 17 of how I realised my dream of becoming a novelist)

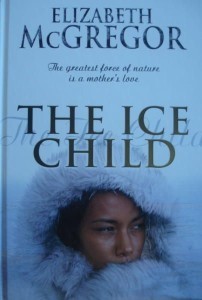

A few days before the first meeting of the writers group that I’d joined, I went to Waterstones in Dorchester. There on the shelves were copies of several of the novels written by the author who was going to be running the group. A real published author. Her name Elizabeth McGregor and in a few days I would meet her.

Somehow everything that had happened over the preceding couple of years seemed to come together right there, like it was the vanishing point on the horizon where rail tracks merge into a single, finite destination. Until that moment it had never seemed to get any closer, always something I struggled towards, but that often didn’t seem real. True, I wasn’t actually any closer to becoming a published author myself, but the fact that somebody else had made it, and that I was going to actually meet her and attend her writing group lent my dream a new validity. Perhaps it was really achievable. For the first time since leaving New Zealand I felt as if this was progress. Elizabeth McGregor and her group represented a door to the actual world of publishing. I entertained a brief fantasy where we would become friends and she, having agreed to read my novel would mentor me and eventually introduce me to her agent who would then secure a publishing deal.

Of course, I was getting ahead of myself. Besides, I wasn’t that confident about the novel I was writing. Some days I felt good about it, even excited as the story continued to take shape. Other days I read what I’d written and was plunged into despair because it was utter shit. Who was I kidding? The characters felt wooden, the scenes pedestrian and I as I struggled to find the heart of the story it was like wading through mud, or like being buried under an avalanche of words that piled up over my head like so much dead kindling. The thought of the group terrified me. Who would be there? They were probably all far better qualified than me, literary types who were more widely read than I was, who had been working on their novels for much longer than I had and had probably already published the odd short story or whatever. I didn’t even have a degree. I’d never published a thing in my life, even though I’d once told people differently, mostly girls I met at parties. I’d once worked for the summer on the Isle of Man, spending the evenings pulling pints behind a bar and the days tapping out short stories on a portable typewriter that I’d bought from a second-hand shop. The stories were about failed marriages and sex. I was twenty-one and though I didn’t know anything about marriage and not a lot more about sex, I showed the stories to a young woman on reception in the hotel where I was working in an attempt to impress her. I was a fake and as soon as I turned up at this group everyone would know it.

Despite my misgivings, I knew that I wouldn’t pass this opportunity up. I bought one of Elizabeth McGregor’s books and spent the next day reading it from cover to cover. The reviews on the back cover were impressive. The writing was described as ‘compelling’ and ‘impressive’ by the Telegraph and a literary magazine. I found the novel depressing because it was apparent from the first page that Elizabeth McGregor was a far better writer than I would ever be. Her descriptions of people and places were spare but immediately evocative. She painted pictures with a few deft brushstrokes, mood and light suggested through subtle blending on the palette, whereas I used a housepainters brush to daub broad swathes of colour straight from the can. Nevertheless, at the back of my mind I wondered a little bit about the story. It was described as a psychological thriller and though I wasn’t entirely sure what that meant, I had the feeling that the story was less about what actually happened and more about the internal machinations of the characters. I supposed that was why it had the psychological tag and why the story felt less like a thriller and more sort of dense and intelligent, but also, I had to admit, just a tiny little bit slow. Even tedious. It was further evidence of my own crude intellect, I thought, rather than a failing of the novel. I’d often felt this way about novels that were described as ‘literary’.

The meetings were held at the author’s home, at seven p.m. on Wednesday evenings. When I’d phoned the number on the ad the woman who answered sounded matter-of-fact and quite chatty with an accent that was hard to place, but vaguely southern England. I arrived at six-fifty-five because punctuality had always been a thing for me. The house was a fairly ordinary semi in a street of identical semis that looked as if they’d been built a quarter of a century ago. I was vaguely disappointed, having imagined something with a driveway and gates, one of the Georgian houses that I’d often admired in Dorchester. There were one or two cars parked at the kerb. A cigarette glowed behind the windscreen of one and smoke wafted out the open window. Another aspiring author, I thought. Maybe I wasn’t the only one who was feeling slightly nervous. I waited a couple of minutes before grabbing a folder of work that I’d brought along. When I spoke to her on the phone, Elizabeth had urged me to bring something I’d written.

“It’ll give me a chance to see what sort of writing you do,” she said.

I’d agonised over what to take. I mean, I’d had a complete novel rejected, so did I take that? Three hundred and fifty typewritten pages for her to cast her eye over. Maybe she would become engrossed by the story, barely pausing to make dinner. At night, sitting up in bed, she’d turn to her husband with a slightly astonished expression, sounding perhaps even the tiniest bit envious.

“My God, this is amazing!” she’d say. “Of course it needs work, it’s rough around the edges, but I think he really has something.”

“Who is it?” her husband would ask. (I imagined him as a professor of something at the university, though I was fairly sure there wasn’t a university anywhere nearby)

“He’s the one I told you about. The one who came here from New Zealand with his wife and their baby after his business went broke or something like that.”

You can see why I’d always wanted to write novels. I was constantly making them up in my head anyway.

Anyway, in the event I decided that particular fantasy was fairy unlikely to eventuate, so I’d brought along about twenty or so type-written pages from my novel-in-progress. I was fairly nervous about doing this, but I thought the opening scenes were actually quite good and did manage to strike the tone and feel I wanted for the entire book, and some positive feed-back would be a huge boost for me.

I rang the doorbell, conscious that the smoker I’d noticed had taken my cue. I heard a car door open and close behind me and glanced over my shoulder as a youngish man, early twenties I thought, crossed the street.

“Hello!” The woman who opened the front door beamed at me with a very slightly wild look in her eyes. She exuded nervous energy as she shook my hand and ushered me inside. “Oh, you’re Stuart then. You can hang your coat there if you like, then come through and meet everyone. They’re not all here yet. There’s some nibbles and something to drink. Kate, that’s my daughter will show you. And Ken’s in the kitchen. My husband,” she added, already looking over my shoulder to the young man behind me.

While Elizabeth repeated herself I went through to the living room where a group of chairs had been arranged in a semi-circle around one in the middle facing out. I counted ten chairs in total, though there were only two other people there besides myself. They were middle-aged women, one who seemed a bit surly and the other very nervous. As we introduced ourselves she smiled, never looking me in the eye and when I offered my hand she looked at bit startled, staring at it for so long I wondered if there was something objectionable sticking to my fingers. I was saved by the arrival of a pretty pre-teen girl with long dark hair who offered me a cocktail sausage from a plate.

“Dad’s got wine in the kitchen if you want some,” she said politely.

“Thanks.”

I wandered through in the direction she indicated, hoping that there might be other drinks on offer too, something strong and lots of it. I wished I’d thought to bring something. The man in the kitchen shook my hand.

“Ken,” he said. “Fancy a glass of wine?”

“Stuart. Yes, thanks.”

He handed me one of the mismatched glasses. He seemed pleasant, about my own age and down-to-earth. Not at all professorial. We chatted about nothing for a few moments before the young man who’d followed my arrival appeared. He was given a glass of wine and we drifted back to the living room where he told me he worked in an electronics shop in the town and was interested in Science Fiction. He mentioned the names of some authors I’d never heard of, occasionally looking up when somebody new arrived. They were nearly all women, mainly ranging in age from roughly mid-thirties to late middle-aged. All of them exuded the same slightly earnest, bookish manner that made me think of libraries and tea groups. Another man arrived, a few years older than me, perhaps in his mid-forties. Something about the way he dressed and his general manner reminded me of my Geography teacher at school from twenty-five years ago.

The last to arrive was another young man in his twenties at which the science-fiction fan I’d been speaking to looked hugely relieved and the two of them gravitated to one another and immediately formed an alliance that would last for as long as they attended the group, which actually turned out to not be very long. It was clear that whatever they’d expected, this wasn’t it. At the end of that first evening I heard them arranging to go to the pub and there was no disguising their eagerness to get away, nor the them-and-us attitude that they’d already developed with all the smug condescension of the young. I was a bit hurt that they didn’t ask me to join them, even though by the end of the evening I felt no more affinity with them than I did with anyone else there.

That first evening was an awkward affair, though in retrospect it couldn’t have been anything else. Elizabeth, who became Liz to us all, was surprisingly nervous about the whole thing. The snacks and wine were a token of social convention, but there was a bit too much of a feel of tokenism about it. I could imagine Liz telling her husband she didn’t want to make a fuss, just a glass of something from Tescos and some of those sausages on a stick or whatever, and that’s exactly what was served, but I couldn’t help thinking she would have been better to offer everyone a glass of bubbles as a kind of celebratory introduction which would have struck a different note. Or else she could have left out a trolley with glasses and scotch and some ashtrays, which seemed more writerly to me. As it was I felt less like I was at a meeting of writers, and more like I had stumbled into a meeting of the organising committee for the local fete. Only much later did I realise that Liz had started the group because she wanted to meet other writers herself, but when she put the ad up in the library she had no idea who would turn up, or if in fact anyone would actually come. She had put out ten chairs because that’s how many phone calls she’d received, but her great fear was that only one or two would be taken, the rest remaining empty, yet another rejection when a writer’s life is already full of rejections, as I’d already begun to discover for myself.

Once everyone had taken a seat, to start the evening off Liz asked us to introduce ourselves and say a little about why we were there. I’d ended up on the extreme left of the semi-circle which made me the last to speak. One by one the others offered a brief biography of themselves, which included some standard traits-in-common, primarily that everyone there was an avid reader of books. I was relieved to learn that they weren’t all teachers of English Literature at universities or that they worked for prestigious magazines or in some other profession connected with the world of publishing, and neither were they all exclusively readers of what I’d loosely thought of as literary works. Most read popular fiction and liked a variety of genres, authors and styles. They all had different backgrounds. Housewives, schoolteachers, shop workers, accountants; there was no common thread there. They shared another trait too, which I realised as they each explained why they’d decided to attend a writer’s group. Not surprisingly, they wanted to become published authors, mostly of novels, but at least one I remember of poetry. What did surprise me was that I couldn’t see evidence that they’d brought their work with them. I was conscious of my manila folder containing crisp pages of typewritten, double-spaced prose. Whereas one or two others had a handwritten page or two torn from a lined pad, most hadn’t brought anything. I’ll admit to feeling a bit smug about this, like the obnoxious swot at who sits at the front of the class and brings teacher an apple.

During these introductions Liz asked somebody how they actually went about writing and this provoked a general discussion.

“Sometimes I get up at two in the morning because I’ve had a great idea and I just have to write it down,” the young science-fiction fan offered. “I might not write for days or weeks other times. It depends how I’m feeling. I have to be in the mood. I can’t just sit down and write like it’s a job or something,” he added as if writing was the antithesis to anything that might be considered work or a job, which he clearly thought of as contemptible.

Others voiced their agreement. “I often think of things when I’m doing the ironing,” one woman said. “I should write them down because the trouble is I forget.”

“It’s difficult isn’t it?” another sympathised. “I’ve got dinner to make and housework and things to do, so I don’t get much time for writing.”

A common theme emerged, which was that most people didn’t have much time to do any actual writing, and when the urge took them it was often at an inconvenient time.

When it eventually came to my turn to speak, I was very conscious that the way I thought about trying to become a novelist was quite different from the others. I explained very briefly how I’d moved back to England from New Zealand after a career in sales had imploded, and that I’d made the move with the express purpose of trying to write a novel. I told them I’d written one novel already, which had been universally rejected by everyone I sent it to, but I was working on another.

“The thing is, to me this is a job,” I said. “We all have jobs because we have to make a living, and the way I see it writing novels is no different. It just happens to be the job I want to do. So I treat it that way. I work from nine until three or four every day and during that time I try to meet a minimum word-count. It doesn’t matter if I don’t feel like it on any particular day. I do it anyway. I don’t see how it’s going to happen otherwise.”

I could sense that nobody agreed with me. One or two looked a bit bemused, as if I’d just made some outrageous statement that nobody could really take seriously, but most seemed a little bit hostile for some reason.

“You can’t force something like writing,” one of them said. “It doesn’t work like that. It’s creative. You make it sound like going to the office and doing some tedious job.”

“Yes,” somebody agreed a bit snottily. “I’m sure that’s not how writers really work. You can’t create art by treating it like a common job.”

“I’m sorry, I think you’re labouring under a misapprehension,” I said. “I’ve read interviews with working writers, and without exception they produce books by working exactly the way I do. They have a set routine where they write for a period of hours a day, because if they didn’t do that, the books wouldn’t happen. And whether it’s art or craft, popular novel or work of literature, that’s how it’s done. It happens bit by bit, page by page, rewrite by rewrite and it’s sheer hard bloody work and if you think you can do it when the muse strikes you, you’re deluded. And the proof is right here.”

I gestured with my manila folder of typewritten pages and as I looked around at them with their empty hands the point couldn’t have been any more eloquent.

There was a bit of a stunned silence. It wasn’t the first time in my life that I’d shot from the hip and managed to make myself unpopular and I didn’t suppose it would be the last. I knew I could have put my position across a little more tactfully, but I had put everything on the line to try to achieve something I’d dreamed of doing all my life. Dale had put her faith in me, and she and Mac were relying on me to make good. I lay awake nights worrying about the future, thinking about money as much as about the book. I was used to people thinking I was a bit mad for doing this, but no matter what they said I was proud of myself because I was trying as hard as I knew how. I was belting out my word count every day, forcing myself to write when it felt as if there was nothing there, and by the time I stopped I was often dizzy and cross-eyed from the effort. Even though I felt like I was drowning half the time, reaching out for something that I felt was just beyond my outstretched grasp, I told myself that if I kept at it I’d find it in the end.

I hadn’t known until then how much I wanted to talk to people who were going through what I was. I wanted to share stories of the struggle and the sheer hard work, of forcing myself to rewrite the same chapter over and over, not even sure what was wrong or what I was looking for, just knowing that it wasn’t right. Not yet. But these people who’d gathered in Liz’s front room weren’t even writing. They were waiting for the muse to strike, for the prefect moment to arrive when that novel would burst out from them in a creative torrent of brilliance. It was bullshit. It was a fairy story and it made me furious that they had the gall to sit there and tell me I was the one who was doing it wrong.

I was ready to get up and leave before I got thrown out. Then Liz cleared her throat and everyone l ooked at her. It was Liz’s group after all, though we’d all momentarily forgotten that. She smiled in the kind of tactful, apologetic way that doesn’t come easily to me.

ooked at her. It was Liz’s group after all, though we’d all momentarily forgotten that. She smiled in the kind of tactful, apologetic way that doesn’t come easily to me.

“Actually, Stuart is quite right,” she said. “That is the way it’s done.” And she ought to know, I thought, because nobody else there was a published author.

She held out her hand for my folder. “Can I take that?” she asked.

I could’ve kissed her.

January 20, 2014

The Pursuit of Happiness (Part 16 of how I realised the dream of becoming a novelist)

To my slight surprise, by the end of summer The Snow Falcon was beginning to feel like a real, actual novel. In the first draft the central character was an ex IRA hitman on the run who finds redemption in a story involving an injured wild falcon and an emotionally damaged mother and child. When I began the re-write I ditched the hitman aspect and opted to make my character emotionally damaged himself, not as a result of violence in a war-zone (which I knew nothing about) but because of the repercussions of a troubled childhood.

As I wrote the second draft I found this theme of people being formed by early life experiences applied to all my main characters. Everything they did and how they interacted with each other was rooted in their own particular histories. There were no straight out good guys and bad guys. They were flawed characters who made both good and bad decisions, sometimes selfish, sometimes selfless and often falling somewhere in between. They were struggling to do the right thing, but often coming up short. In other words, every one of them was instantly recognisable because they seemed like people anywhere. They were real.

As I wrote the second draft I found this theme of people being formed by early life experiences applied to all my main characters. Everything they did and how they interacted with each other was rooted in their own particular histories. There were no straight out good guys and bad guys. They were flawed characters who made both good and bad decisions, sometimes selfish, sometimes selfless and often falling somewhere in between. They were struggling to do the right thing, but often coming up short. In other words, every one of them was instantly recognisable because they seemed like people anywhere. They were real.

There was a time somewhere around the onset of autumn when I felt like I experienced a kind of epiphany. I suddenly and unexpectedly felt that everything was changing, that the stars were lining up for me on this writing thing. I had a routine that I stuck to with a sort of puritan zeal. I went up to my room at 8.30 every weekday morning, sat at my desk and meditated for about fifteen or twenty minutes. I’d never done this before but at some point it had felt like it was worth a shot and so I closed my eyes and tried to relax by imagining myself sitting cross-legged on top of a hill with my hands in my lap, palm up, absorbing the rays of the sun through the top of my head, the light energy then suffusing throughout my entire body. I could see this light energy in my minds-eye and it made me feel as if I was literally glowing and getting physically lighter and at the same time expanding. It was a strange experience, and elusive in the sense that I couldn’t always get there because my mind was running off in a hundred different directions all the time. Random thoughts about the story I was writing popped up, or something about Mac or Dale or a bike ride, what we were having for dinner. Whatever. It was like being in a maze and being able to see the central point I was trying to get to, but all the time I kept taking these detours.

I tried to explain it to Dale. “Imagine you’re looking straight ahead all the time, so your eyes are totally focused, but the ground sort of shifts under your feet, very subtly tipping you this way and that and then your focus slides towards that direction without you even being aware of it.”

The explanation was due after Dale unexpectedly appeared at the door one morning and found me having a nap, as she drolly remarked. Usually I would have heard her coming, but this time I hadn’t, so I’d had to explain what I was doing. I was slightly embarrassed because at that time to me meditation was synonymous with a diet of lentils and salad leaves along with crystal healing and other New Age stuff practised by slightly odd and earnest people. I can’t even remember now what prompted me to try it, but it probably had something to do with a ticking clock and dwindling finances.

Dale’s reaction was typically pragmatic. “If it works, great.”

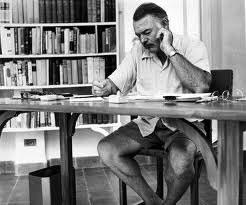

Probably just as well I didn’t tell her about the part where I spoke to all the dead writers whose books I’d ever read and loved and asked them to give me a break and a bit of a helping hand, just channel some of the creative talent they’d possessed my way. Hemingway was one that I particularly called on. Maybe I didn’t let on about that exactly, but one evening over dinner I did tell Dale something interesting about Hemingway.

“You should read one of his books,” I told her. I slid a copy of For Whom The Bell Tolls across the table. “You could start with this.”

“What’s it about?” she wondered, looking dubiously at the thickness of it.

There really wasn’t much point in telling her the story revolved around the Spanish civil war, though like any great war story the themes are much deeper and more universal. Dale wasn’t a reader of novels full stop. On the rare occasion that she did have one by the bedside, it took her such a long time to get through it I couldn’t fathom how she could remember what it was about from one week to the next. I sometimes wondered if we weren’t an odd match. Here was I, trying to become a novelist, married to a woman who didn’t read. How could we talk about books and plots and character and all the rest of it? Well, the answer is we don’t and never have and actually it suits me. I’ve learnt that just as kids benefit from the differing traits of both parents, the typically male and typically female (which can exist in either sex by the way, before I’m accused of being anti-gay parents, which I’m not), so it seems that in all aspects of life there is something to be said for the adage that opposites attract. Negative needs positive and vice-versa. It’s the constant interaction between two polarities, continually trying to achieve balance that seems to be the nub of existence. The result isn’t a constant state but a vacillating wobble between directions. A vibration somewhere in the middle ground.

Anyway, I’m digressing. Dale and I get along without having a common interest in books and writing. I’ve found that when I’ve talked to other writers, I don’t really want to talk to about books and writing with them either. I’m happy to keep it all in my head, which is probably the same for other writers too. It’s the ideas that matter in the end, what lies behind it all.

So getting back to Hemingway, I realised I wasn’t trying to persuade Dale to read one of his books. I wanted to talk about the man himself. “He was a real macho kind of guy,” I told her, showing her his photo on the inside cover. Bushy grey beard, squat head and broad features. It was a photo taken later in life. “He wrote about the civil war and bullfights and before that about the First World War. He was an ambulance driver, which gave him first-hand experience.”

As I spoke I could see her eyes glazing over. She was thinking about the sauce she’d made or something. The thing I wanted to tell her though was that Hemingway had this reputation as a big game hunter, a game fisherman, an adventurer, which were all traits shared by his characters and his novels were alive with people like that. But here was the thing; Hemingway’s early childhood couldn’t have been more different from the person he became.

“For the first few years of his life, his mother dressed him as a girl, grew his hair long and called him Ernestine.”

When I read this fact about the great man, I started reading all of his books again and I saw them in a completely different light. I’m not trying to write an essay about Hemingway here so I won’t get diverted into discussing his portrayals of male and female characters and the way he writes about sex. The point I was making to Dale was that authors, like everyone else, are driven by the influences that formed us, some obvious and others less so.

When I read this fact about the great man, I started reading all of his books again and I saw them in a completely different light. I’m not trying to write an essay about Hemingway here so I won’t get diverted into discussing his portrayals of male and female characters and the way he writes about sex. The point I was making to Dale was that authors, like everyone else, are driven by the influences that formed us, some obvious and others less so.

As I rewrote the Snow Falcon, Michael was emerging as this isolated, lonely figure with a troubled past. The whole town is against him, but outwardly he just continues stubbornly on his path, though he’s not even sure what he’s doing. He’s attracted to his neighbour and she to him, but both of them, for different reasons, deny the attraction. In Susan’s case this affects her relationship with a cop who is basically a good man but can’t stomach the thought of losing for a second time the woman he’s always loved. It’s Susan’s troubled ten-year old son who becomes the focus of this conflict. Then there’s Ellis, a character who started out not really having much of a role in the story, but inexplicably came alive, along with his wife, Rachel. Ellis needs money in the mistaken belief that if he had some he could fix his broken marriage. A rare falcon might provide him with that money, but after Ellis takes a shot at the falcon and wings it, it’s Michael who finds it first. The story of Ellis’s losing battle against resentment and jealousy and how he always manages to do the wrong thing was becoming an essential part of the overall plot. His long-suffering wife, lonely and looking for a way to escape how her life had turned out was becoming drawn to Michael, which made put her into subtle conflict with Susan who was drawn to him through her son.

Right at the centre of the emerging book was Michael. It was his past that was the key to his actions and to everything else in the story. It was why the townspeople didn’t want him around, but it went deeper than what he did, it was about why he did it. That was what he was trying to figure out. In the story, he owns an empty building that his dad ran as a hardware store when Michael was growing up, and for Michael this is the where the heart of the story lies. He has to face the truth that lies buried deep down inside so that he can live with himself. The story of the boy and the falcon illustrate his journey to redemption. In scenes of winter mountains and spruce forests, of snow and ice and wild flowers emerging when spring arrives, I had started to bring these different threads together so that all the characters had their own redemptive journeys to fulfil by the end, though the constant ever-growing threat of Ellis threatens to derail them all.

All the stars were lining up, like I said earlier. I began to feel excited, like I was actually on the verge of something, though I could hardly allow myself to believe it. It sounds as if I planned this novel out meticulously. All these intersecting lives and strands of plot, with metaphors and themes wherever you look. It wasn’t like that though. After I finished meditating I’d pick up the story where I left it the day before. I’d write new scenes more often than try to polish existing ones, churning out words at a fantastic rate. Four, five six thousand a day sometimes. A lot of them got deleted in subsequent drafts, but this was the only way I could tap into the creative stream, where the story and all of the nuances flowed up from some unconscious reservoir. But even though the stars were lining up, it didn’t happen overnight. I never stopped thinking about the story even when I was sleeping. I dreamed scenes and wrote them the next day. And all the time that I was writing and thinking about writing, I had thoughts about my dad who I hadn’t seen for more than twenty years. He lived less than two hours away by car. We had driven through the town where he lived on our way to the village where I spent the first few years of my life.

In the book, Michael begins fixing up the old hardware store and by doing so confronts memories of his childhood and his dad in particular. One day I wrote a scene that I hadn’t planned. Michael’s parents are long dead, but he hadn’t spoken to his dad for many years prior to the event that killed him. What memories he allows himself are bitter, angry ones. So why is he fixing up this store? And why when he’s driving into the mountains to train the falcon, does he remember something that seems at odds with his perception of his dad? Michael has taken to bringing Jamie on these trips. Jamie is Susan’s troubled, silent ten-year old son, and while she worries about letting them be together, they remain largely silent, the falcon the only real point of contact between them, except what lies underneath. It’s Jamie who sparks the memory, reminding Michael of himself.

I’m posing these points as questions, because at the time I was writing the novel I didn’t realise what I was also doing was dredging up my own past. They say writing is cathartic and certainly it was for me. When I mentioned my dad to Dale she always urged me to contact him.

“Just a phone call. What harm can it do?”

I didn’t know why I didn’t call. Or maybe I did, deep down, I just didn’t want to admit it or have to think about it.

In any event my thoughts were diverted elsewhere for a time at least, when Dale came home from Dorchester one day and showed me an ad she’d seen for a writers group.

“It’s run by a published author. Why don’t you call?”

“I will,” I agreed, though the idea made me a bit nervous. A real published author. I assumed I’d have to show this author my stuff, maybe other people in the group too. What if they thought it was no good? I had invested everything into this. Money, time, our family’s future, my sense of who I was. That last consideration outweighing everything else. Joining a group could force me to face unwelcome truths. Did I want to do that?

So in the end I didn’t make the call.

No, that’s not true. I did. A week later on a midweek evening I drove into town and began a very interesting experience.

December 27, 2013

The Pursuit of Happiness (Part 15 of how I realised my dream of becoming a novelist)

I looked ahead to where the path joined what looked like a farm track to climb towards a ridge. Beyond that there was only the blue of the sky, devoid of clouds, and my brain was boiling. Dave was in front as he always was, pedalling steadily, and, I realised, pulling away from me. One minute he would be twenty feet ahead and every atom of my being would be focused on keeping up with him, on keeping those pedals turning despite the pain in my thighs and calves, and my laboured gasping as I tried to suck in enough air. Then something would catch my eye, maybe a fox trotting along a hedgerow or a buzzard soaring overhead or a vista of undulating countryside that suddenly opened up as we rounded a bend or crested a hill. I’d slacken off the pace just for a few seconds to absorb whatever had caught my attention and when I remembered Dave, he’d have pulled away from me, stretching the gap from twenty feet to fifty yards and I would have to put on a burst of what felt like superhuman effort to catch him again. I rarely did. Eventually he’d realise what had happened and he would slow down. I could see him, idling along with no apparent effort as he waited for me to catch up.

enough air. Then something would catch my eye, maybe a fox trotting along a hedgerow or a buzzard soaring overhead or a vista of undulating countryside that suddenly opened up as we rounded a bend or crested a hill. I’d slacken off the pace just for a few seconds to absorb whatever had caught my attention and when I remembered Dave, he’d have pulled away from me, stretching the gap from twenty feet to fifty yards and I would have to put on a burst of what felt like superhuman effort to catch him again. I rarely did. Eventually he’d realise what had happened and he would slow down. I could see him, idling along with no apparent effort as he waited for me to catch up.

“Alright?” he’d say.

“Fine.”

And on we’d go. He had a much better bike than me. That’s what I told myself, anyway. The ride we were doing that day was one we’d only done once before. I remembered that half way around the route I’d begun to have serious doubts about whether I could make it all the way. It covered forty miles over paths and bridleways that were marked on the map, but appeared to have been largely forgotten. In parts we’d had to ride through nettles and weeds that came up to the handlebars, jolting and bumping over unseen pot-holes and exposed tree roots, even having to resort to dismounting and lugging our bikes over our shoulders at one particularly steep climb where the path simply vanished. It was less like a ride than an assault course. When we’d arrived back in the village I was exhausted, stung and bruised. Every muscle ached. I slept for twelve hours solid that night. So when Dave had suggested doing the same route again a few weeks later, inwardly I groaned while outwardly I attempted to match his enthusiasm.

He showed me the map. “Remember that bit where we had to carry the bikes? I think I found another way we could go there.” He traced an alternate route around a wood. “It’s a bit longer, but it should be easier.”

A bit longer. Great. On the other hand I couldn’t face that climb again, carrying what felt like half a ton of steel on my back.

The ridge we were approaching was about half way along the route. It was a hot day with almost no wind and I was drenched with sweat and steeling myself for the climb. I refused to look again in case the reality of how steep the track was and how distant the ridge appeared to be put me off entirely. Instead I thought about the view once we got there, and every biker’s reward, the long downhill slope towards a hamlet that I remembered on the other side.

The climb was gruelling and the only thing that kept me going was my determination to keep up with Dave. When we’d begun these rides together he would often have to wait for me at the top of hills and I hated knowing he was watching me gasping and groaning the last hundred yards or so. He never said anything but he couldn’t disguise the slightly amused look in his eyes. It had become a point of honour for me to reach those pinnacles along the way no more than a few seconds behind him. On this occasion I managed it. While Dave surveyed the view, one foot on the ground still sitting in the saddle, I got off and unceremoniously discarded my piece-of-crap- made-in-bloody-China bike. My arse was killing me. I was wearing proper bike shorts, but as far as I was concerned there wasn’t near enough padding in them, even though I looked like was wearing one of Mack’s nappies. My head felt like it was cooking as I ripped my helmet off and threw it into the grass and guzzled water from one of the two bottles I carried.

Once I’d recovered a bit I had to admit the effort had been worth it. The ridge we’d reached was high enough to allow a view for miles in every direction across the heart of the Dorset countryside. We were surrounded by farmland defined by hedgerows and woods. Fields of grass and ripening wheat made a patchwork of greens and golds among the folds and contours of the land. Larks trilled high above us, fluttering specks in the air, while rooks complained and flapped around the tops of some distant trees. A church spire emerged from a far-off canopy of green, betraying the presence of a village beside a stream that ran through a valley marked on the map. To the south was Tolpuddle, where the martyrs had come from. I’d seen the sign beside the road one day. In the early eighteen hundreds a group of farm workers had formed a society to protest at the lowering of wages that happened as a result of mechanisation. This was at the time of the birth of the union movement and though unions weren’t illegal the men had sworn an oath, which, according to an obscure law, meant they had broken the law. They were tried and sentenced to seven years transportation to Australia as convicts, though popular support meant their sentences were later repealed.

From that ridge, looking over countryside that hadn’t changed much in a hundred years the Tolpuddle martyrs didn’t seem so long ago. I was reminded that this was Thomas Hardy country too. He was born several years after the Tolpuddle case, but a nearby village called Puddletown was the inspiration for the town of Weatherby in Hardy’s novel Far From The Madding Crowd, which I’d read at school. I mentioned it to Dave, though he’d never read any of Hardy’s novels.

“How’s your book going, then?” he asked.

“Pretty well, actually.”

“What’s it about?”

I described the basic premise of a man who returns to his hometown after an absence of years. Nobody wants him there because of an event in the past that saw him serve a prison sentence. An early scene where he visits the graves of his parents tells us that they are dead, but also that Michael has confused feelings about them. He disliked his father and hadn’t spoken to him for years before he died. As the novel progresses it becomes clear that the events of Michael’s childhood were the catalyst for the events that occurred later, which ended his marriage and resulted in his loss of contact with his daughter. It’s these inward issues that preoccupy Michael rather than the hostility that the people of the town feel towards him, but both themes come together when he finds an injured falcon in the mountains.

It was sort of a long answer to Dave’s question.

“So it’s not like a thriller then?”

“No.” I wasn’t really sure what genre it fitted into. “It’s a drama, I suppose,” I told him. Was there even such a genre? Did it mean anything to call it a drama? In many ways it was a love story, because there was a strong plot-line about Michael’s neighbour, a woman who lived with her young son, both of whom had issues of their own to deal with. But calling it a love story seemed to ignore everything else that it was about. In fact the novel was about three or four sets of characters who all represented the town and the their attitudes in various ways, and who all had their own issues arising from their pasts, and all these storylines came together in the central story of Michael’s struggle to come to terms with his feelings of guilt, remorse and anger. Hard to capture that in a word or two.

“Do you think it’ll get published?” Dave asked. “I mean really?”

“I don’t know,” I answered honestly.

“What will you do if it doesn’t? Will you get a job?”

“I’ll have to.”

“There’s not much around down here,” he said, which he knew because he’d spent several months unsuccessfully looking for a job after he was made redundant from his last position.

“No luck then?”

“No chance. It’d be different if we went back to Birmingham or somewhere like that, but I don’t fancy that.” He hesitated. “You know what I’d really like to do?”

“I’d like to go and live in Spain.”

I was surprised. He’d never mentioned it before. “What would you do there?”

“We could get work as sort of travel consultants. You get employed by these companies who sell holidays to Brits and you’re job is to meet them when they arrive and sort of look after them, give them information about what to do and where to go and all that sort of thing. I’ve looked into it.”

I tried to picture Dave doing a job like that. It wasn’t hard. He was a friendly, sociable person and he liked to do be busy and active, especially outdoors. I knew he’d had some kind of management job before I met him, but I got the impression he hadn’t liked it much.

“Sounds great,” I said. “What about the language?”

“We’d soon pick it up, but we’d be dealing with Brits most of the time anyway. The money’s not great, but I worked out if we sold the house and were careful we could manage until something better turned up. I think it’s a case of just doing it and worrying about the details later.”

He talked enthusiastically about the climate, about the relaxed lifestyle and how different it was from England.

“The people are different there. They seem a lot happier. It’s all about being outside, eating good, fresh food; biking, walking, the sea…” He made an expansive gesture. “All that kind of thing. It’s all a bit depressing here sometimes.”

Dave’s wife worked as a teacher, a job she didn’t enjoy. I could see them living this other life he described. “What about the kids? How do they feel?” I wondered, knowing they were at that early teenage point where they might be reluctant to move. Dave’s face fell.

“That’s the problem,” he said. “It’s their schoolwork.” He talked about the difficulty of moving them just when the elder one was approaching his exam years. There were international schools in Spain where they could follow the same curriculum, but the cost would make things difficult. He mentioned other issues they’d have to deal with, like selling the house in a stagnant market, his wife giving up the security of her job and so on.

The more he talked about the negatives, the more his enthusiasm waned.

“Do you ever regret what you did?” he asked me eventually. “You must have had a good life in New Zealand. When you talk about the weather and the beaches, having barbecues and living outdoors more and all that, it sounds great.”

“I suppose it is a pretty good lifestyle there,” I said. “The climate’s not as good as Spain, but it’s better than here.”

“So why did you leave?”

The question surprised me. He knew it was because I wanted to write a novel and I always told people I felt I needed to be close to the London publishing scene to have a decent chance at it. It was only partly true. It was also a convenient way of escaping a failed business and I had felt the need to reconnect with the place where I was from. But as I explained some of those things, I realised that Dave wasn’t really listening.

“Aren’t you worried it will all go wrong though,” he said. “I mean, what if you don’t get published? You’ll have nothing.”

“You want to know if it’s been worth the risk, is that it?” I said, getting the drift.

“I suppose so. I keep thinking about Spain and wondering if we don’t do it now, maybe we never will. Maybe I’ll get a job and that’ll make it harder.”

“Because then you’ll have more to give up?”

“Yeah. It’ll be riskier then, won’t it? And the housing market might pick up. I mean, when the best time to sell? How do you know?”

Dave was asking all the questions Dale and I had asked ourselves back in New Zealand. I told him that there are no real answers, at least not the kind he meant which were to do with security and money. “It’s got nothing to do with any of that stuff. For me, it’s not even about writing a novel, even though that is what I’ve always dreamed about.”

“Why did you do it then?”

“Because I couldn’t face the idea of getting a job and going back to how I was living before. Getting up every day, going to work at something I didn’t care about, paying the mortgage, just the same old stuff. Plus Dale was pregnant so the whole family thing was about to happen and I could just see my life stretching out in front of me and I didn’t like the way it looked very much.”

As we talked I looked around. From my perspective, Dorset looked pretty good. I loved the countryside and the fact that it was criss-crossed with paths and bridleways, and on that day at least, the weather was pretty good. The difference between Dave and me was that I was there because I wanted to be there, and I was doing something I wanted to do. In reality I could have stayed in New Zealand and tried to write my novel there, but I realised it wasn’t so much about whether one place was better than another and juggling all the variables like lifestyle and climate, cost of living or whatever else; sometimes it’s just about change.

“It’s the price we pay for our comfortable lifestyle isn’t it?” I said at one point. “The jobs, the houses and cars and TVs and all the other stuff we surround ourselves with, they tie us down. Life is predictable and safe. And limiting.” Limiting was the key thing. “If I stay here long enough, I’ll be back in that situation again. I’ve broken out for now, just like you want to break out and go to Spain. But if you do go and you end up staying long enough, maybe you’ll start feeling the same way again.”

It was really change that Dave wanted, I thought. It was change that I’d wanted too. Not just the change from doing a job I didn’t particularly like to writing novels, something I was pretty sure I would like, but a change of routine, of rhythm, of surroundings and experiences. That was what Dave wanted and I told him that for what it was worth, I’d never regretted our move for an instant.

“Our lives become prisons of our own making,” I said, philosophising with what felt like a line I’d heard somewhere else, but was happy to claim as my own. “I suppose that’s why people dream about uprooting and living somewhere else. What we really want is new experiences. It’s easy to say, but if I was you, I’d go to Spain.”

Eventually I picked up my piece-of-crap bike and we continued our ride. From the ridge where we’d been whiling away the time, we rode down a long, rutted slope towards a patch of woodland that gave way, briefly, to a tiny village. I knew that soon we’d hit a difficult stretch and even though Dave had figured out a way around the worst part, we still had some hard riding ahead. I didn’t care though. I loved those rides. I loved the vistas of fields and woodland, the villages with thatched cottages and churches that had been standing for centuries, and knowing that Thomas Hardy had probably walked some of these same paths (though I didn’t like his books much) and that the Tolpuddle martyrs had met in one of these buildings to swear a secret oath. I would never have taken those rides and experienced those things if we hadn’t left New Zealand and if I hadn’t met Dave.

When I thought about our conversation later, it seemed to me that over recent years when I’d felt disillusioned and vaguely unhappy about life, it was probably because I was bored as much as anything else. I wondered if things would be different if I’d moved every few years, the way I had when I was in my late teens and early twenties. It was only as I got older, when I started having a career instead of a job, a house with a mortgage instead of a flat, that I began to feel this oppressive weight settling over me. I tried to imagine a life where change was constant, where Dale and I, along with Mac and whatever other kids were in our future, would uproot and move on at regular intervals, living in new countries, meeting new people, having new experiences. It seemed exciting, but also, I had to admit, it might be a bit wearying after a while. Could people even live like that? Didn’t kids need stability and continuity? Besides, how would it even be possible, unless I really was making a living as a novelist? Surely some kind of portable job like that would be essential. But I realised even that wasn’t true. There are jobs and ways of making a living anywhere, it just requires thinking outside the square. The one thing you have to give up to live like that is security, I thought. That’s what it comes down to. Security or Freedom.

As for Dave, he never stopped talking about going to Spain, even after he landed a job about a month later running a local tourist attraction.

December 23, 2013

The Pursuit of Happiness (Part 14 of how I realised my dream of becoming a novelist)

Nothing worth having comes easily. There are a lot of different ways of saying it, but like most clichés it is absolutely true. The more pain, effort and struggle it takes to achieve something, the more worthwhile it will prove to be. I used to think it was an apt way of thinking about the struggle I went through to write my first published novel, with success being the worthwhile payoff at the end of it all. It wasn’t until much later that I realised that though the success was great, the real reward was actually more meaningful and had nothing to do with money. It was about the things I discovered about myself along the way, so in my case it really was the often difficult and sometimes painful journey, rather than the ultimate destination that meant the most.

During the s ummer of 1997 I’d been playing around with a story about a character called Michael, who returns to the town where he grew up after an absence of many years. I knew he was a loner, but that was about as far as I’d got other than to picture a remote setting surrounded by wintry mountains. Re-reading the Goshawk after twenty-five plus years had made me think about a pair of kestrels I’d raised and trained when I was about fourteen, which gave me the idea of using a falcon in my novel, so I took Dale and Mac to a falconry centre in Dorset to remind me of what it was all about. Seeing the falcons flying after a lure swung by a trainer brought back a flood of memories, so I tried to explain my idea to Dale.

ummer of 1997 I’d been playing around with a story about a character called Michael, who returns to the town where he grew up after an absence of many years. I knew he was a loner, but that was about as far as I’d got other than to picture a remote setting surrounded by wintry mountains. Re-reading the Goshawk after twenty-five plus years had made me think about a pair of kestrels I’d raised and trained when I was about fourteen, which gave me the idea of using a falcon in my novel, so I took Dale and Mac to a falconry centre in Dorset to remind me of what it was all about. Seeing the falcons flying after a lure swung by a trainer brought back a flood of memories, so I tried to explain my idea to Dale.

“Michael has come back to his hometown, okay. He keeps to himself. There’s some kind of issue he’s dealing with, something that troubles him. Then he finds an injured falcon and he decides to try to kind of nurse it back to health and train it so that it can learn to fly again…”

As I talked, I was half-watching a falcon diving from hundreds of feet above the field we were standing in to try to grab the lure that was tied to the end of a line being swung in an arc through the air by the trainer. I imagined a scene like this in my novel.

“So you’re writing an animal story?” Dale said, and I could tell she was a bit surprised because it was a bit of a departure from the haunted houses and creepy villagers that had featured in my last attempt at a novel.

She was right though. She’d hit on the issue that was rapidly deflating the excitement I’d been feeling for the past few days. I didn’t want to write an animal story and as soon as I realised that, I understood that actually that wasn’t what I had in mind.

“It’s not about the falcon,” I said. “I mean it’s partly about the falcon, but really it’s about Michael and who he is. The falcon is kind of like a metaphor.”

“For what?”

I had to think about that. “For what’s wrong with him. His issue.”

“So, what is wrong with him?”

It was a reasonable question, but I was annoyed. “Jesus! I don’t know. I haven’t got it all worked out yet.”

I wasn’t really annoyed with Dale, though that’s the way it came out. Her questions made me realise that I didn’t have the answers, which meant I was excited about a book I really didn’t know how to write. I didn’t have a story, I had an idea and a few scenes in my head and that wasn’t enough. I sulked for a bit because it was easier than admitting I didn’t know what I was talking about. We trudged around the centre a bit more, showing Mac the hawks and falcons, though he was more interested in the ice-cream he had managed to smear all over his face. I found myself wishing Dale was the kind of person who would understand what I was trying to get at, then we’d sit down under a tree and have a discussion about themes in great novels that we’d read. We’d take them to bits and analyse what made them work and somehow out of that discussion Dale would come up with some ideas and suggestions and I’d start to get a better feeling for how the story could take shape.

There were a couple of problems with this imagined scene. Firstly Dale wasn’t much of a reader and never had been. It hadn’t mattered to me much when we first started going out together, in fact I’d never really thought about it. She had other qualities that attracted me, like the fact she had a hugely outgoing personality, something I’ve never been able to claim, lots of friends (ditto – I had a few), she loved outdoorsy stuff like jet-skiing, biking and so on – stuff I’d always sort of wanted to do but never had until I met her. As I thought about all of this it occurred to me that we were complete opposites. It also occurred to me that while I was wishing Dale was somebody other than who she was, which I knew I didn’t really wish at all, she might very well be having similar thoughts about me.

“Sorry,” I said.

She was on her knees, feeding Mac more ice-cream while he beamed and waved his arms around with enthusiastic appreciation.

“What for?”

“You know…” I knelt down beside her and kissed her and I took my turn at giving Mac some ice-cream. “Lucky bugger.”

“Why? You can have an ice-cream if you want.”

“Ha ha, you’re hilarious. I mean he’s lucky because he doesn’t have to worry about anything does he? Give him an ice-cream and he’s happy. That must be the best thing about being a kid don’t you think? You can just have a good time and let your parents do all the worrying.”

Dale took my hand and squeezed. “It’ll be alright. You’ll work it out.”

“We’re running out of time. If I don’t get it right, we’re screwed. We’ll have to go back and I’ll have to try to find another job, which I’ll hate, and I’ll spend the rest of my life thinking I’m a failure.”

“Hasn’t happened yet. We’ve got enough money to last another year, more or less.”

“Less, actually.”

I was glad that Dale didn’t seem as worried as I was. I knew I should be glad that I was lucky enough to have somebody so supportive. And I was glad. But I also felt a little ungenerous twinge of resentment. I felt that I had this enormous weight on my shoulders to write this book and find a publisher and save us from disaster, and instead of making me feel better, Dale’s support added to the pressure. It was ridiculous and I knew it, but it didn’t change how I felt. It was like her faith in me gave me even more to live up to. I lay awake at night thinking about it. Moving to England to try to write a novel had been my idea. All mine. I remembered telling Dale that somebody had to write novels for a living, so why not me? What was so outlandish about the idea anyway? Especially given that it had always been my dream. She could have asked why I hadn’t done it already then, given that I was thirty-seven at the time. She could have asked to see all the uncompleted novels I kept locked away somewhere, the books of notes, the plans, the characters, the snatches of dialogue I planned to use someday. She didn’t though, which was lucky because I hadn’t done any of that. I loved novels and I’d read a lot of them and always thought I’d like to write one, but the truth was I hadn’t done any writing since I was about twenty-one when I spent six months living on the Isle of Man, but even then I’d only really bashed out some short stories in an attempt to impress a girl I liked.

So every day after breakfast and Teletubbies with Mac, I went to my room and wrote. I realised that this was all my doing and I couldn’t expect any help from Dale, so I stopped talking about the book. I told her how it was going. If I felt I’d had a good day, I told her and she was pleased for me, and if I’d had a bad day I told her that too and she’d ask if I wanted to talk about it and I’d say not really.

“It isn’t that I don’t want to exactly, it’s more that I don’t know how to. It’s hard to explain.”

What I meant was I didn’t understand the story I was writing. I was just writing, letting the words pour out of me, trying to paint pictures of the scenes I saw in my head and at the end of the day I’d have a lot of words, sometimes four or five thousand, never less than three. I wrote good scenes and bad scenes, but the problem with it all was it didn’t really seem to be going anywhere. I still didn’t really know what it was about. At one point I had the idea that Michael was an IRA hitman on the run from his former friends who were intent on killing him. That explained why he was a loner and suspicious of people, and they were suspicious of him because he was taciturn. I decided he hadn’t returned to his hometown, but had been relocated a place he’d never been to before. Saving and training the falcon was a metaphor for healing himself, it was about his past, and all the time his old mates were closing in.

I pretty much wrote an entire draft of that story, and then one day I decided that it wasn’t right and I knew I’d have to start again. The funny thing is, it wasn’t a bad story. In many ways it wasn’t so very different from the novel I eventually wrote, but there was a crucial difference. I’d created a cast of characters to populate the story and one of the things I’d discovered was that I liked writing characters from their individual points of view. Whatever their role was in the story I looked for something in their make-up, in their past experiences, that made them who they were and explained why they behaved the way they did. It was the actions of the characters that created the story, but just as importantly it was why they acted the way they did that seemed to make the story breathe and come alive. The only character who I really didn’t understand was Michael. Nothing he did rang true to me. I invented a past for him, but it didn’t feel right. I just couldn’t put my finger on why.

At this point I still didn’t have a title. It was set in New Zealand in the alps, around a town called Queenstown which is a winter ski resort. The falcon was a New Zealand falcon, which is the only falcon native to the country. Then one day I bought a Sunday paper and in the magazine supplement was an article about a woman in England who trained falcons. I can’t remember much about the article, but I still have the full-page colour photograph of a very attractive blonde woman holding a very big and strikingly beautiful, almost white falcon on her fist against the background of the Y orkshire moors. The falcon was a Gyr, an arctic breed which is the biggest and reputedly the swiftest of all falcons, and by ancient lore fit only for an emperor. They are sometimes known, because of their colouring and habitat, as snow falcons.

orkshire moors. The falcon was a Gyr, an arctic breed which is the biggest and reputedly the swiftest of all falcons, and by ancient lore fit only for an emperor. They are sometimes known, because of their colouring and habitat, as snow falcons.

That day I pinned that picture to the wall above my desk and I wrote the title of my novel for the first time. The Snow Falcon. I changed the location to Canada and I began thinking about Michael again.

December 21, 2013

End Of Year Update

I’ve just written episode 14 of my ongoing blog, put I won’t post it for a couple of days yet. In the meantime I wanted to let you know that I’ve been working on a novel for the past few months and I’ve just about finished the second draft. I’d hoped to have it done and dusted by Christmas, but I’m a bit behind. It should be finished by March though, at which time It’ll go off to the publishers, though an ebook version will be available more or less straight away.

This novel is set in New Zealand, which is a first for me. It’s a crime story that revolves around a mayoral election in Auckland, the country’s biggest city, and draws on the backdrop of the legalised prostitution scene there. So it’s sex, politics and murder, always a good mix, with a collection of interesting and complex characters and a plot that mixes mystery with thriller.

I chose to set this one in New Zealand because this country is much more on the world-map these days. There are films, music and books making it big on the international stage, written and made by Kiwis, and I wanted to add my point-of-view to the mix. The Auckland and surrounds I’ve portrayed features some of the suburbs and areas that have a distinct flavour of their own, whether upmarket or grunge, and I’ve made the sub-tropical weather that the north sometimes gets a particular motif in the book, which gives it a slightly exotic feel of palm trees and the islands, of muggy heat and afternoon deluges, which is different from the way the country is often perceived overseas. Anyway, more about that in the new year.

Other plans next year include making print versions of the revised version of Snow Falcon, The Flyer and a re-worked version of what is now the Black Sun Anthology widely available. More on those plans as they come to fruition.

In the meantime, the posts will keep coming. For those in the northern hemisphere, have a great Christmas and New Year and stay warm, and for us in the southern hemisphere, ditto but stay cool and don’t forget the sun-screen.

December 14, 2013

The Pursuit of Happiness (Part 13 of how I realised the dream of becoming a novelist)

On a hot day in June, we decided to go to Bournemouth because somebody had told us there was a really nice beach there. When we arrived half of southern England was there too.

“This is nice,” I said to Dale with only a trace of irony. I wish I’d taken a picture of her face, but this was before everyone had phones with cameras. In 1997, which is not really that long ago, most people didn’t have mobile phones, and the Internet and email were still pretty much unheard of outside the offices of big corporates. I’m digressing though. Dale was staring at the sea of bodies, looking a bit gobsmacked.