The Sound of Doors Slamming (Part Six of How I Became a Novelist)

Nobody enjoys rejection. One of my early teenage memories is of approaching a girl I liked at a disco to ask her to dance. The excruciating walk across the expanse of the community hall between records, through the spectrum of coloured lights cast on the dusty floorboards which foiled my attempts at invisibility. All the girls on one side noticing my approach, whispering to e ach other, waiting to see who I had in my sights. Conscious of the boys behind me, grinning and nudging one another, eager to witness somebody’s humiliation so long as it wasn’t their own. Finally I was there, irreversibly committed. I attempted a confident smile which somehow became a terrified grimace. Her eyes, which I saw up-close were an even more startling shade of blue than I had realised, widened, conveying a silent plea which I understood was meant to spare me, but it was too late. The words I had imagined speaking with casual ease fell from my mouth like bricks.

ach other, waiting to see who I had in my sights. Conscious of the boys behind me, grinning and nudging one another, eager to witness somebody’s humiliation so long as it wasn’t their own. Finally I was there, irreversibly committed. I attempted a confident smile which somehow became a terrified grimace. Her eyes, which I saw up-close were an even more startling shade of blue than I had realised, widened, conveying a silent plea which I understood was meant to spare me, but it was too late. The words I had imagined speaking with casual ease fell from my mouth like bricks.

“Do you want to dance?”

Following this, several seconds of silence as I unconsciously held my breath, as did the rest of the room, or so I imagined. Time slowed to a crawl. My heart thudded.

“Sorry, me and my friend are going outside,” she said with vague pity.

Of course they were. Only then did I realise that the agony of the walk there was nothing compared to the return, weighed down by the humiliating burden of rejection, the silence like an unbearable shriek, every step taken with limbs that behaved as if they belonged to somebody else. I prayed for the DJ to play a record and was sure I caught him watching my walk of shame with a glint of malicious amusement. He waited until I reached the company of my friends where I could look forward to being mercilessly mocked, before he put a record on the turntable. It was Jimmy Cliff singing I Can See Clearly Now, which seemed like an ironic choice to me.

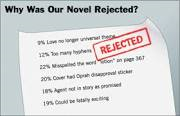

The first novel I ever submitted to literary agents reminded me of that occasion at the disco. I can vividly recall watching through the window when the postman arrived each morning. As he delved into his bag my heart would race and my breath catch in my throat. I prayed for an ordinary, everyday business-sized envelope containing a letter from somebody eager to represent me. What I dreaded was something much larger and fatter, something big enough, in fact, to contain the first three sample chapters of my novel which I had submitted to fifteen agents carefully chosen from the Writers and Artists Yearbook for 1997. I was pretty confident that at least one of them would love what I’d written. Fifteen times I was proved wrong. Fifteen times I heard the thud of my manuscript being returned as it hit the floor in the hall. On some days I suffered the double or even triple humiliation of hearing not one, but a series of thuds. Inside there was always a form rejection letter. Regrettably my novel wasn’t considered appropriate for this agency blah blah. The echo of that girl from more than twenty years earlier rang in my ears.

agents carefully chosen from the Writers and Artists Yearbook for 1997. I was pretty confident that at least one of them would love what I’d written. Fifteen times I was proved wrong. Fifteen times I heard the thud of my manuscript being returned as it hit the floor in the hall. On some days I suffered the double or even triple humiliation of hearing not one, but a series of thuds. Inside there was always a form rejection letter. Regrettably my novel wasn’t considered appropriate for this agency blah blah. The echo of that girl from more than twenty years earlier rang in my ears.

“Sorry, me and my friend are going outside – and the book you’re going to write one day won’t be any good either.”

They say that rejection is something an author has to come to terms with, to accept as an inevitable part of the journey to becoming published and I have found that no truer words have been spoken. I’m in a new phase of my writing career now and I’m experiencing the blunt force of rejection again, but I’m older and wiser and probably a bit battle hardened, so it doesn’t hurt so much these days. Seventeen years ago, however, it felt a bit like the sky was falling.

By the time the rejections began coming in, it was early spring. Dale and I sat down over dinner and a glass or ten of wine to take stock. The plan appeared to be unravelling a bit. Our money was dwindling at a constant rate, Mac was already six months old, and it didn’t look as if a publishing contract would materialise anytime soon. I needed to have another go, I told Dale. I’d recovered from the initial kicking to my ego and after a sober analysis of my novel I concluded that there were issues. What it came down to was that the manuscript I’d sent out wasn’t really part of a finished novel. I had written what amounted to a corrected first draft. It had taken me about three and half months, and I thought if I spent the same amount of time again on rewrites, I might have something worthwhile at the end if it all. There was a problem, however, inasmuch as I was no longer at all sure that I wanted to write horror novels. I’d never really chosen horror as a genre anyway, it just sort of turned out that way as I unconsciously expressed how I felt about the village we had ended up in. Nothing had worked out the way I’d imagined it would, and my unconscious mind had worked all my tangled fears and disappointments out through a story about a young couple who found themselves pitted against a range of malevolent forces. I’ve since learned that writing is often unintentionally cathartic.

I decided that rather than rework my novel, I would attempt something completely different, and this time I’d take more time to ensure I got it right before I sent it out. Having made that decision, I thought it would be a good idea to make a fresh start in other regards too. I didn’t really like the cottage we were living in, or the village, or the postman, or the pub along the road with its regular trio of unfriendly patrons. When I suggested to Dale that we should move, she agreed, and we began looking straight away. It soon became clear that there was nowhere nearby where we wanted to live, so decided to just pack up and look further afield, which is how we found ourselves leaving the village a week later with the car loaded with all out possessions, Mac strapped into his seat in the back, and no clear idea of where we were heading. It was a repeat of what had brought us to England, and to Devon four or five months earlier. We were running away from another failure, chasing that elusive rainbow, or at least I was, though I was oblivious to this at the time.

As we passed the pub for the last time, the landlord happened to come outside. He saw the laden car and me behind the wheel and he must have guessed we were leaving and to my surprise he raised his hand to wave. As I automatically returned the gesture, it struck me that he had never meant to be unfriendly, rather it was simply that people who live in places like that, who have probably spent most of their lives there, are by nature very reserved. They had never mocked me as I’d imagined. If anything they were bemused by my presence. I spoke with a funny accent (having picked up a New Zealand twang during my years living there) and (as the postman would have told everyone) I was trying to be a writer. I know now that people regard novelists as oddities. They spend all day making up stories in their heads, which doesn’t seem like a real job. Somebody once asked what kind of books I write and when I talked about the genres I have dabbled in he looked puzzled.

“You mean they’re all lies then?” he wondered, grasping that I was talking about fiction.

It turned out he’d never read a novel in his life. I imagine that the landlord of the pub and his friends hadn’t either. In retrospect I think they found me perplexing. A man should drive a tractor or build a barn or even run a pub, occupations that were of some practical use. What was the point of writing books? And as I looked in the rear-view mirror and saw him go inside again I also heard him add to that; Especially ones that, according to the postman, nobody wanted to read.