Mark D. Jacobsen's Blog, page 7

September 1, 2020

What I’m Reading: August 2020

The book cover images are hyperlinks through Amazon.com’s affiliate program. Purchasing through these links provides modest support for this blog.

The Good Neighbor by Maxwell King

[image error][image error]I have happy but indistinct memories of watching Mr. Rogers when I was a toddler. I did not give Mr. Rogers much thought in the 30+ years that followed. In the past few years, however, Fred Rogers has surfaced again and again in my reading–not in books about childhood education, or even books targeted at adult nostalgia, but in serious books about character. These treatments revealed an aspect of Mr. Rogers that I had never recognized, or at least had taken for granted: he was a man of deep and authentic character and power, traits which emerged through a lifetime of disciplined spiritual formation.

Mr. Rogers has drawn widespread attention in recent years, with the documentary Won’t you Be My Neighbor? (which I have not yet seen) and the Tom Hanks film A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood (which I have). Arriving between these films was The Good Neighbor, the first and only book-length biography of Rogers. The ever-humble Rogers had long resisted a biography, but towards the end of his life recognized that it was an important part of sustaining his lifelong mission and ministry among children.

You pretty much know what you are getting, plunging into a biography of Fred Rogers: 320 pages about a good and decent man, faithfully married to one woman, who spent more than 30 years carrying out a vocation that he arrived at early in life. It is a biography conspicuously free of vice, conflict, or explosive revelations. For that reason, it sometimes felt like the author needed to stretch for material–recounting numerous summaries of particular TV episodes, touching conversations, or Fred singing It’s You I Like to some guest or another. Yet the book is never boring, and I found plunging into the cool waters of Fred Roger’s life deeply refreshing. Even when repetitive, the book felt like a meditation on decency; it was a welcome alternative to almost every other source of media I consume.

As a writer and entrepreneur, I enjoyed learning more about Fred’s creative process and discovering that, in addition to being a natural TV presence, he was an extremely prolific and talented artist, musician, and entrepreneur. He was deeply rooted in strong values, to include vehement opposition to marketing to children, which meant the viability and success of his shows was never guaranteed. Because of his values Fred Rogers and to work twice as hard to realize and sustain his dream of nurturing young children through television, but that same commitment to values is what allowed him to pull it off.

Fred Rogers has drawn so much interest in recent years largely because his decency, goodness, and faithfulness to a sense of calling are so sorely absent in modern times. Civility has become the foremost casualty of our political climate, while hatred, division, and mockery are now celebrated as virtues. In his Afterword, King touches on critics who believe that Fred Rogers ruined a generation of children through excessive coddling. Yet for those who are not quite ready to surrender kindness and compassion as vices, Fred Rogers’ life still gives us hope that a better way is possible. As David Books writes in an op-ed about Rogers, “moral elevation gains strength when it is scarce.”

Atlas Shrugged by Ayn Rand

[image error][image error]Speaking of kindness and compassion being vices…

I have had Ayn Rand’s 1,088-page magnum opus on my shelf for years but finally summoned the energy to read it, helped along by a friend who agreed to read it simultaneously.

Atlas Shrugged is one of the most complex, profound, powerful, and disturbing books I have ever read. I have seldom read a book that required me to think so deeply, or one that evoked such a broad range of emotions. For those reasons, its standing as a classic is well-deserved. With that said, it is a work of mad genius–literally. Rand’s genius flashes through repeatedly, but she strikes me as a deeply disturbed person whose self-righteous hate, by book’s end, reaches a fevered pitch of insane obsession. The book’s shortcomings are severe, and I find it frightening the degree to which policymakers reach for the book as a basis for policy.

The novel focuses on a small, heroic band of industrialists who are responsible for most of the economic process in the United States. Heroine Dagny Taggart runs operations for the Taggart Transcontinental Railroad; she must repeatedly outmaneuver her inept brother Jim Taggard, who consistently makes disastrous decisions that sacrifice the railroad on the altar of social good. Hank Rearden is a steel magnate who underpins nearly the entirely industrial economy, but who is widely despised for his windfall profits. As the novel unfolds, these productive capitalists who sustain so much of the United States find themselves under relentless attack by “looters” who regulate, steal, undermine, sabotage, condemn, and otherwise seek to destroy them–all in the name of social progressivism, brotherly love, altruism, and other perverse vices. In response, the enigmatic “destroyer” John Galt vows to stop the motor of the world. The book is an extended reflection on what would happen if the world’s most productive capitalists essentially went on strike. It flows directly out of Rand’s underlying philosophy: reason is supreme, self-interest is the highest virtue, and altruism is an evil that diminishes human dignity.

The book has extraordinary power, and Rand’s imagination and prose can be breathtaking. A family member recommended the book to me after my painful experiences founding and leading an innovation team within government, which put me in constant conflict with entrenched defense bureaucracy. Parts of the book spoke to my soul; as I watched Dagny Taggart pull off one miracle after another to outmaneuver ignorant bureaucrats and drive progress, my heart soared with recognition. One of the most spectacular moments in the book comes when Dagny rides a new rail line for the first time, a line she has struggled against all odds to build.

The character drama can also be rich, complex, and nuanced. Early on, Hank Rearden gives his wife Lilian a precious gift–a bracelet, the first object he made with a new kind of steel he has developed. The value of this gift is predictably lost on Lilian, but a profound turning point arrives early in the novel when Dagny spots the bracelet on Lilian’s wrist at a party. The three-way interaction between these characters is extraordinary, with insinuation and subtlety making for a far more powerful story than raw action or melodrama ever could.

Rand’s critique of misguided social values is poignant and insightful. She rightfully defends the dignity of the human individual and the centrality of reason. She powerfully demonstrates the risk that charity or altruism can actually undermine human dignity. She offers a devastating critique of political, social, and economic groups who seek to tear down the very builders of the prosperity they enjoy. There is a kernel of truth to Rand’s savage distaste for “looters.” And in fiction, it is a valid technique to use hyperbole–to push a point to imaginative excess, to make the point stark and clear, to burn an impression into the reader’s mind. 1984 did this masterfully.

The problem is that I’m not so sure Rand intended to be hyperbolic. Atlas Shrugged is a 1,100 page obsessive diatribe against a straw man. By book’s end it has been pitchforked, dismembered, beheaded, burned, urinated on, and kicked a few times for good measure.

A straw man is “an intentionally misrepresented proposition that is set up because it is easier to defeat than an opponent’s real argument.” It is hard to see Atlas Shrugged‘s argument as anything but that.

Over and over again, foolish business executives make disastrous decisions to sacrifice profit in the name of the public welfare. I have encountered many inept bureaucrats in my life, as well as many purveyors of leftist ideologies I consider dangerous. However, I have never met this species of corporate executive who is hellbent on doling out his company’s profits to others. These characters are so commonplace in the book that it is hard to take the critique seriously.

Atlas Shrugged presents a false dichotomy between two types of characters: a tiny productive caste of industrial barons, and vast hordes of soulless looters who would tear them down. Most of us, when we are young, love good vs. evil stories. As we mature, we have to learn that the world does not simply consist of good guys and bad guys; the line between good and evil runs through every human heart. That is difficult to grasp because it makes the world a far more complex and difficult place, which demands much more careful moral reasoning. However, Atlas Shrugged leaves no room for this subtlety; Rand’s small cadre of noble industrialists are the only characters exhibiting any virtue, while the unwashed masses have no redeeming qualities. Rand’s critique smacks of profound hubris and a deep hatred for most of humanity.

When I look at the world, I do not primarily see noble monopolies driving human progress while parasitic startups try to loot their wealth. That certainly happens sometimes, but the conventional wisdom about monopolies is that they risk becoming looters; monopolies tend to underperform and use political connections, cash reserves, or other forms of market power to block the rise of promising competitors.

The behaviors Rand detests are observable in almost any company or individual. Even the most productive companies leverage government to their benefit. When COVID19 hit, every business was trying to get tax breaks or subsidies, big or small. The savviest business operators are also the first in line to apply for government relief after natural disasters. We are all self-interested. Even those of us who value hard work and like earning our keep usually take advantage of every legitimate opportunity to come our way; that is part of what it means to work hard.

If the vices Rand detests are found at every strata of modern society, so are the virtues she cherishes. In the real world around 600,000 Americans start new small businesses each year, while millions more are educating themselves and trying to build their futures. Yes, a small percentage will be among society’s most productive, but the rest are not simply looting; many are trying in their own way.

As for the tension between self-interest and altruism, many scientific disciplines–to include evolutionary biology and game theory–have converged on the notion that instincts for both self-interest and cooperation are deeply encoded into our DNA, that both can align, and that both are necessary for human happiness and flourishing. Rand’s moral universe is far too black-and-white to tolerate this level of complexity.

Finally, Rand’s moral universe leaves no room for inequality of opportunity and the way this rigs the game. Heroes like Dagny Taggart and Hank Rearden, as well as villains like Jim Taggart, appear as fully-formed adults from the vague primordial soup of the author’s imagination. In this world, there are only self-made men and looters. It does not matter to Rand–does not appear to occur to her, in fact–whether the deck was stacked in favor of her heroes from the beginning. This is the fundamental issue at the heart of right-left debates about white privilege, structural racism, government redistribution, and social welfare programs. Rand’s critique cannot serve as the basis for real-world policy when the chief argument of her ideological rivals is missing entirely.

There is room for vigorous debate about all these issues, but we cannot simply wave them away. Towards the end of the book, one of Rand’s characters rails against “some barefoot bum in some pesthole of Asia” and the “mystic muck of India”, contrasting them with entrepreneurial individuals–presumably white Americans–who use reason to build advanced technology. That diatribe made no allowance for overt oppression that keeps some people subjugated to the benefit of others. If we allow evils like plantation slavery or King Leopold II’s Congo Free State into the universe, Rand’s critique looks more brittle.

As a work of fiction, the book’s value sags and then collapses around two thirds of the way through. It would have been stronger at half the length. The last few hundred pages are painfully tedious. The first rule of storytelling is “show, don’t tell“, but Rand can’t help herself. By book’s end, a character makes a 60+ page speech that reads like a rambling university essay, telling the reader exactly what she meant to express through fiction in the previous 1,000 pages. Rand comes across as a woman possessed.

Overall, Atlas Shrugged is a powerful and engaging book. It contains forceful, important critiques. Rand is right about a lot. But at the end of the day, Atlas Shrugged is an adolescent fantasy. High fantasy novels give shy teenagers access to entire worlds in which they wield swords or bows, slay monsters, woo princes or princesses, possess magic abilities, and discover forgotten birthrights. Atlas Shrugged does much the same thing for savvy entrepreneurs who feel maligned by the world, abused by incumbent powers, or made to feel ashamed of their gifts and aspirations. It is a fantasy in which the geniuses are finally recognized for who they are, and their despised enemies finally get their due. I love a good fantasy as much as the next person, but at the end of the day, fantasy is fantasy. The real world demands more of us.

Reboot: Leadership and the Art of Growing Up by Jerry Colonna

[image error][image error]Jerry Colonna has carved out a fascinating niche for himself as one of the most beloved CEO coaches of our time. The founder of Reboot, Jerry does not teach strategy, tactics, or organizational design; he is more like a spiritual guru and therapist who guides leaders on journeys of radical self-enquiry. Jerry is a voice in the wilderness for lonely executives who silently carry the burden of leadership and do not know where else to look to nourish their souls.

Jerry is a delightful anomaly. In a business world where concerns of the soul are carefully kept out of sight and relegated to other domains of life, he feels perfectly comfortable asking CEOs to bare their souls. He writes frequently of “brokenhearted warriors”, language that might make us shift uncomfortably in our seats but also appeals to something deep within us. He references poetry, Buddhist philosophy, and vision quests. In his podcast he cuts right through the protective bubble wrap of social etiquette, asking his guests deeply personal questions.

All of those peculiarities make Jerry a treasure for the modern business world. We need more of what he brings. In addition to being an experienced founder and investor, Jerry is a kind, thoughtful soul who overflows with gratitude for both his own journey and the opportunity he has to help other CEOs on their own journey.

Reboot is an extended reflection on Jerry’s own journey and lessons he has learned from coaching other CEOs. It is well-written, engaging, sometimes unfocused, and frequently beautiful. The book is a gentle introduction to Jerry’s style of coaching, and is sure to provoke thoughts and reflections about one’s own journey. It also points a hopeful way forward for how we can address soul-deep needs in the challenging domains of business and leadership.

Perennial Seller: The Art of Making and Marketing Work That Lasts by Ryan Holiday

[image error][image error]Ryan Holiday is one of my favorite authors–not just because he writes insightful books about Stoicism relevant to modern life, but because he is a serious craftsman. Holiday takes the art and craft of writing seriously.

That is why I loved his book on creating and selling work that lasts. Like many creative types, I have always felt an instinctive tension between craftsmanship and marketing. I have bruised feelings from living in a world in which artless or dishonest hacks strike it rich, get funded, or find wide readerships, while the honest, dedicated craftsmen go unrecognized. As I have grappled with my own writing career (more specifically, my failure over 20 years to get one going), I knew this was a self-limiting belief that I needed to overcome if I was ever going to make it. Some cursory Googling led me right back to Ryan Holiday, to this book which I hadn’t known existed.

Although probably lesser known than his other books, Perennial Seller is the best book I have read on marketing for creatives. The book begins with a passionate appeal for craftsmanship. Holiday starts with the premise that there is no substitute for doing the hard work of writing the best books we are capable of writing. Yes, we can probably make a living by churning out a lot of average material, but the books that endure are masterpieces that serious writers carefully labored over. Craftsmanship is the foundation on which everything else is built. From there, Holiday goes on to write about positioning, marketing, and platforms. If you are a creative who struggles with marketing, you won’t find a better book to help you find your way.

The Hard Truth: Simple Ways to Become a Better Climber by Kris Hampton

[image error][image error]Kris Hampton is the voice behind The Power Company podcast, which I enjoy listening to while training for climbing. He has distilled 26 blog posts and essays into a new book aimed to kick the reader’s ass into overcoming self-limiting thoughts and behaviors.

This is a book specifically for climbers (mainly plateaued intermediate climbers)–but for those who climb, it also speaks to life. This was a fun book that any climber will enjoy. I appreciated the frank tone. It could have used better editing, but was otherwise a solid read.

August 28, 2020

7 Models of Bureaucratic Innovation

Over the last ten years, government has at least theoretically embraced the idea of “innovation.” New innovation organizations are popping up like mushrooms. Poor private sector; every time they think they have figured out how to work with government, some new organization appears on the scene to shake things up.

This widespread culture shift toward innovation is generally a good thing. However, time and again, I have seen innovation organizations appear that do not have a clear purpose, business model, or theory of innovation. Despite good intentions and strong support, many of these organizations struggle to create enduring value. Some hold a plethora of glitzy events without ever moving money, developing prototypes, or running experiments. Others write proposals and build prototypes but never scale these early concepts into wide-scale adoption. So much innovation activity dissipates like water into sand, while government rumbles on as it always has. I suspect similar dynamics occur in many large companies attempting to become more innovative.

Over many years pondering these challenges, I have developed some basic models of common innovation approaches. These models can:

Help you intentionally develop a theory and strategy of innovation for your organization

Suggest reasons your strategy might not be working

Help you understand where your organization fits in a broader landscape

The models are simple by design and hardly comprehensive, but they offer a basic scaffolding for deeper thought about your own unique situation. No one model is right or wrong.

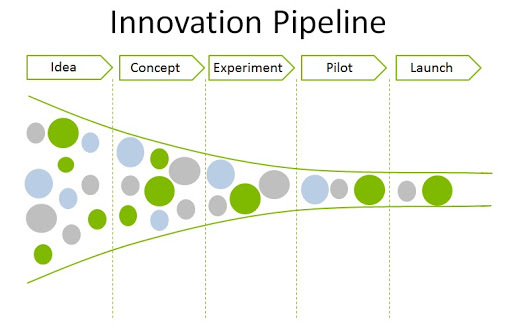

The Core: Innovation Pipelines

Innovation is a process of discovering and implementing value-adding changes for customers. These might include physical technologies–like new hardware or software–or social technologies like strategies, processes, workflows, or ways of organizing.

Customers could refer to literal paying customers of a product, but they could also be stakeholders within an organization or community who stand to benefit. In my defense work, my customers were usually warfighters who needed every tactical advantage on the battlefield.

Systematic innovation efforts involve an innovation pipeline. Above is just one example I plucked off of Google, largely because of its simplicity. You can divide out the stages many different ways, but a pipeline generally includes the following:

Idea generation: Gather as many ideas as possible, good or bad; we deliberately keep a wide aperture.

Prioritization and filtering: Prioritize ideas in accordance with our organizational needs, resources, and values. Identify the ideas worth pursuing.

Refinement: Explore both problems and solutions, widening the aperture again to consider both from every possible angle. Turn the idea into a viable concept, which represents an educated hypothesis about a potentially valuable innovation.

Experimentation: Commit progressively more resources to experimentation, learning, and iteration. Test and refine the hypothesis to see if this idea is worth scaling.

Scaling: Scale the most promising ideas into wide-scale execution. This might mean releasing a new product, changing a policy, etc.

Software introduces some modifications, since you can take early ideas into production immediately and then iterate in place, but you get the general idea; if your goal is actually implementing change at scale, then you need a start-to-finish pipeline.

The goal

The ideal innovation pipeline would look something like this:

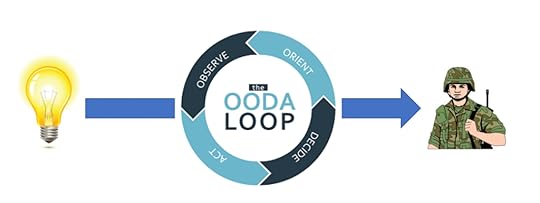

Assuming your organization is in a competition with adaptive adversaries, you need to act quickly. Whatever your pipeline looks like it should run fast. You need a faster OODA loop than your opponents, which includes observing your environment, educating your judgment, making decisions, and then acting swiftly and decisively.

You want to identify and implement value-adding changes for your customers with the greatest speed and efficiency possible.

Model 1: The Status Quo

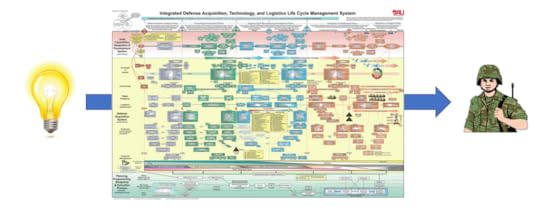

If you are in a large organization like the Department of Defense, your innovation pipeline looks more like this:

The chart in the middle is an actual diagram of the DoD’s acquisition process, which I chose mainly because it is so easy to pick on. The details aren’t important. This box, whatever it contains, represents all the convoluted bureaucracy that stands between a promising idea and scaled implementation. This is how we get to $10,000 toilet seat covers and $800,000 ammo rounds that are too expensive to fire.

Innovation does actually occur in this model. In fact, it occurs all the time.

That box includes a vast network of research labs, prototyping initiatives, and means of production. It includes systematic processes for every step of the innovation pipeline to include soliciting ideas, developing requirements, assessing feasibility, conducting experiments, doing limited-run production, testing, evaluating, and incorporating feedback. The system has delivered F-22s, aircraft carriers, and nuclear submarines. All those little boxes on the chart exist for a reason: in theory (!!!), they illuminate and/or reduce risk.

Every organization has its own version of this chart, which expresses how value-adding changes are realized and executed.

Before you found a new innovation organization, you need to know why this incumbent innovation process is not meeting your needs.

Many defense innovators would probably struggle with that question.

I will save my full answers for another day. For now, it’s enough to say that this pipeline works very well for certain kinds of problems but very poorly for others. It is intolerably slow when dealing with fast-evolving technologies like software, computation, or machine learning.

The impetus for more speed and agility largely drives government’s search for for alternative innovation models.

Model 2: The Idea Factory

This model rests on a hypothesis about what is wrong with the current innovation pipeline: senior management need help finding the right ideas.

When I assisted with founding the Defense Entrepreneurs Forum, this was our basic belief. We knew our senior leaders were sharp, dedicated, and talented professionals. We also knew they were swamped with hard problems and did not necessarily have the time or energy to solve all those problems themselves.

We believed that an organization of dedicated young military professionals could apply their collective brainpower to some of these problems and help generate solutions. The first DEF conference included two-day long “ideation” sessions, in which teams went to work on a curated set of problems. This culminated in pitches to a panel of general officers and investors.

With years of hindsight, I believe we misdiagnosed the problem. Our innovation model looked something like this:

Can you see the problem? Our model mostly addressed the earliest stage of the pipeline: injecting the right ideas into the funnel. While it’s true that an outsider can generate a truly novel idea, this stage is rarely where innovation gets jammed up. Ideas are cheap; the hard part is the other 99%, which is the execution that follows. Several of our presentations on the last day of DEF were cringeworthy, because in two days of ideation, teams simply couldn’t delve into the practical details necessary to walk an idea down the pipeline into execution. The most successful pitches came from innovators who had been working on a pet idea for years.

There is nothing wrong with brainstorming ideas, but these ideas will most likely be dead on arrival unless the innovation pipeline includes onramps that can get promising ideas to the next stage. Here are some ways to improve on the model:

Connect promising innovators with senior leader champions. The hard part is identifying the right senior leader up front. Placing a senior leader or two on a judging panel is unlikely to bear fruit, because the odds that a particular idea falls within that leader’s scope is minimal. Ideas need the right champion to move forward.

Award prize money. The intent here is to give innovators resources to carry their idea forward. Cash prizes give innovators the most agility, but by themselves, they provide little to no connective tissue with the rest of the innovation pipeline; the idea will only make it a little further before it dies.

Protect innovators to keep them with their projects. On a few occasions, I have seen general officers reach down to hand-select an innovator to keep him or her with a project; this is every innovator’s dream, but it is ad hoc and not scalable. The fact that GOs must reach down from on high to protect an innovator is not a solution; it is evidence of systematic brokenness.

Have established processes to connect promising innovators with organizational resources. This is the best solution, but the hardest for an entrenched bureaucracy like DoD to implement. Ideally, organizations would have built-in infrastructure to advance good ideas (and the innovators standing behind them) to the next stage of the pipeline. That would include budgeted funds, labs, tools, access to structured venues to meet with senior leaders, and–most importantly–talent. The best example I have seen of DoD building onramps was MGMWERX giving pitch competition winners access to Air Force-funded Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) funds in order to put a private sector company on contract.

Despite the shortcomings, this model can be an inexpensive way to cast a wide net, solicit ideas, and give unconventional innovators a voice. It is often the best that grassroots innovators can do.

Model 3: The Brain Trust

This model usually seeks to improve on Model 2. It begins with the recognition that grassroots innovators need senior leader champions to get very far. For that reason, a senior leader who wants innovation might create a “brain trust” of savvy employees who report directly to him or her. In the chart below, all this brainpower is nestled within that leader’s cell on the org chart.

This model improves on Model 2 by committing organizational resources to innovation. In theory, these innovators are given adequate top cover to focus on driving progress. Leading innovation is no longer a volunteer role slapped on top of their day jobs, but the thing they are paid to do day in and day out. The sustained commitment to innovation gives these individuals opportunities to actually tackle execution, and to do so with the boss’s support. The Chief of Naval Operations’ Rapid Innovation Cell (CRIC) comes to mind as a good example; the CNO was able to pull highly qualified talent from the Navy, including key members of DEF.

However, this model also has several challenges. First, for all the intellectual firepower these individuals have, they still comprise just one cell on the org chart. Their ability to work across the entire pipeline might be limited. Brain trusts can be very good at setting experiments or prototypes into motion, but DoD is absolutely terrible at crossing the valley of death between prototypes and production. Second, the survivability of the brain trust is highly dependent on the specific boss; the odds of getting two highly supportive, hard-charging bosses in a row are low. Third, a pool of brilliant employees with tremendous initiative will not go unnoticed, especially when they work in a higher headquarters; the temptation to poach these individuals for various initiatives and projects is high. Innovators may be torn in different directions and may not have adequate white space to focus on core innovation efforts. Finally, it is a key tenet of the literature on innovation in large organizations that innovative teams often need to be distanced from the core enterprise; it is the only way to avoid an incentive system overwhelmingly skewed against experimentation. Brain trusts that work directly for a mainstream headquarters may not be adequately insulated, and may find themselves outmaneuvered at every turn by entrenched interests.

Model 4: The Dedicated Innovation Organization

This model takes organizational resourcing to another level. Instead of relying on volunteers or placing a few key individuals under the protection of a supportive leader, this model involves creating specialized organizations to execute innovation. These organizations receive mandates, budgets, and other resources to own as much of the innovation pipeline as possible.

This model arguably encompasses much of DoD’s new innovation ecosystem. These organizations attract individuals who are passionate about innovation and who are eager to break out of old ways of doing business. They have enormous potential, but are also the most likely to struggle with a lack of clarity about their purpose. The best example I can give is my own DIUx; it struggled during its first year, which led Secretary of Defense Ash Carter to replace the leadership and reboot the entire organization. DIUx (later renamed DIU) later found a better operating model, but that took time. More on that in a moment.

As these shiny new innovation organizations seek to go “innovate”, they tend to land on similar activities, like industry days, collider events, design thinking sessions, ideation days, problem curation, road shows, tech scouting, hackathons, and pitch competitions. These activities can be valuable in their own right. They are fun. They make for great publicity. They feel like innovation.

The problem is that they are nearly all early-stage activities in the innovation pipeline. They are largely aimed at scooping up ideas, assessing feasibility, demonstrating technology, or–for the most mature organizations–advancing a prototype.

This is all good, but it brings a few problems. First, these organizations face deep structural challenges in crossing the valley of death between prototyping and production. Most ideas will die before they are fielded. Second, DoD’s vast number of organizations doing early-stage scouting can create real problems for industry. On the one hand, it is good that private companies have an unprecedented number of opportunities to do business with the government. On the other hand, a company executive could spend every week of the year going to tech demonstration events that never result in contracts being awarded. That gets old very, very fast.

Dedicated innovation organizations need to realize from the outset that crossing the valley of death will be their biggest challenge. Yes, they can have a lot of fun before they fall off the cliff. But if their goal is to create value-adding change for customers, they must solve transition. That means going beyond fun ideation sessions. It means doing the nasty, hard, thankless work of cleaning out the plumbing on the right side of the chart.

Model 5: VFR Direct

One way of dealing with the system is navigating around the system entirely. I call this VFR Direct, the aviation term for navigating straight to a location using your own eyeballs, without relying on instruments or air traffic control.

VFR Direct is where I have spent most of my time in my career. In this model, innovation teams essentially bypass the bureaucracy and use every tactic, technique, and hack at their disposal to get a capability directly to the end user. In my case, as a software developer, this has often meant writing and distributing my own software. As a solo developer I wrote useful programs, shared them with my peers, and created my own website to distribute them. Word spread, and my capabilities found their way into widespread use.

Later, we built Rogue Squadron on this model. Our team benefited from a central funding source, high trust from DoD leadership, and little day-to-day interference, which allowed us–as we said–“to skate where the puck was going.” Our expert team was so attuned to new developments in the drone market that we could leverage new capabilities within weeks or even days of their release, or even plan new capabilities based on expectations of where the drone sector was going. We built relationships directly with warfighter units, built capabilities at their request, and delivered capability the instant it was ready. We built our own web infrastructure for managing and deploying software updates, so we could push code changes in moments to our users across the globe. We crossed the valley of death–for a time–by playing by an entirely different set of rules.

I love this model and always will. This is where I personally thrive, and I believe government needs more teams like this given the accelerating pace of technological change in today’s world. The philosophy of Mission Command is premised on setting intent but allowing for decentralized execution by trusted units. In today’s world, that should apply just as much to capability developers as to infantry. But I digress…

This model does have obvious shortcomings. The bureaucracy theoretically exists to illuminate risk, whereas VFR Direct runs the risk of hiding it (although I believe this distinction is often false in practice–the subject for another article). This model can also obfuscate the ownership of risk because it is sometimes less clear who is signing off on risks.

Furthermore, it is the team’s ability to operate outside of the parent organization that allows it to move so quickly and with so much agility. The downside is that the team has little institutional support when needed. DoD is not structurally capable of providing sustained resources to teams that operate outside its close supervision. These teams must continually take calculated risks by operating outside of normal conventions. They run the risk of antagonizing the establishment and face serious sustainment challenges.

Teams operating on this model also have a complexity ceiling, because more complex projects require more engagement with broad stakeholder groups.

The sweet spot for VFR Direct innovation is probably fielding urgent, niche, time-sensitive capabilities while waiting for the establishment to catch up.

Model 6: Fast Track Innovation

The most mature innovation organizations take ownership of the entire innovation pipeline, from early-stage idea collection to long-run fielding and sustainment. This is very, very hard to do.

One approach is to build an innovation organization around legitimate fast-track authorities that allow for quickly maneuvering through the bureaucratic maze.

After its reboot, DIU focused its business model around Other Transactional Authorities–an acquisition authority originally created to help NASA move quickly in the Space Race. OTA contracts can be fast and lightweight, bypassing much of the red tape that constrains more traditional acquisition processes. This introduces risk in some areas but reduces risk in others–especially if, like me, you believe that speed is its own source of advantage and that moving slowly introduces tremendous, often unrecognized risks. DIU built its own process called the Commercial Solutions Opening, which packages OTAs in an easy package that the private sector can understand and work with.

AFWERX built its own fast-track model around Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) grants, which allow government to put small businesses on contract and then progressively add resources as an idea proves its value. AFWERX’s innovation was not so much its use of the SBIR, but the sheer number of them it doled out. In one day in 2019, the Air Force awarded 51 proposals in 15 minutes or less. The SBIR initiative showed a new commitment to placing small bets, which is generally considered good practice when planning for uncertain futures.

This general approach strikes me as the most promising for accelerating government innovation, but it is not a panacea. I will explore this in future articles, but even fast track authorities are not usually enough to cross the valley of death. DoD has an ever-increasing number of contracting vehicles and funding mechanisms for prototyping, but at the end of the day, programs can only be implemented and sustained if they are programmed into the defense budget. That Byzantine process has a five-year lead time, and funding flows through the very program offices that these rapid innovation organizations are often trying to work around–and often compete with. This puts rapid innovation organizations in a difficult dilemma: if they have an antagonistic relationship with program offices, their experiments will never see the light of the day. However, if they coordinate with program offices from the beginning, they will have to make numerous compromises that will gradually funnel them into the same mindset and behaviors that they were originally founded to escape.

This Faustian bargain is the dirty secret at the heart of defense innovation: to scale beyond prototypes, you have to become just like the thing you sought to avoid. This is where reform efforts must be targeted; nothing will ever really change otherwise.

Model 7: The Coalition Model

For years, I only had the above six models in my repertoire. Over time, I gradually realized that I needed another. This capstone model encapsulates most of my day-to-day experience as an innovator.

The Coalition model acknowledges that there are wonderful people to be found everywhere in that vast, bleak Borg cube of defense acquisition, with its incomprehensible acronyms, endless arrays of office symbols, and soul-sucking processes.

We are all in this mess together, and getting any damned thing from one end of the pipeline to the other is a pick-up game that requires a coalition of hardened fighters.

There are brilliant inventors churning out ideas at the grassroots. There are savvy, insightful commanders trying to move chess pieces around the board to get the best ideas into execution. There are passionate staff officers working in headquarters who want to see change. There are brilliant people working in the program offices who hate the constraints they are under but will use the full envelope of their authority to do the right thing. There are dedicated and loyal civil servants deep within the notorious “frozen middle” who are absolutely essential to getting ideas resourced, approved, and into the field.

When you really delve into a specific problem or solution space, you quickly figure out who the power players are. You find each other on the sidelines of conferences. You meet at dive bars on business trips to plan strategy. You text each other during 75-person telecons, because at the end of the day, you know the five of you will be the ones actually driving change.

My most successful experiences with large-scale innovation came through these kinds of coalitions. A few examples:

Rogue Squadron began when high-level officials in the Office of the Secretary of Defense saw our value, supplied us with resources, and then trusted us to do the right thing; they provided the rails within which we operated, ensuring we stayed compliant and approved.

Later, we built an extraordinary partnership with a major Combatant Command headquarters. We built effective alliances with a rock star team of staff officers, civilians, and contractors at the headquarters, who shouldered the brunt of the “bureaucratic warfighting” and left Rogue Squadron free to keep developing and delivering capability at blistering speed.

DoD recently announced five new trusted quadcopters built for the Army, which will soon be available to the entire government. This extraordinary program emerged from a novel partnership between a forward-leaning Army program office and DIU. The Army program office brought institutional support and requirements, while DIU brought its contracting authorities, private sector relationships, and domain expertise.

Conclusion

Any model is a simplification of a more complex reality. These models are no different. Undoubtedly there are many ways to divide up the complex landscape of innovation activities across an enterprise as vast as DoD, but these models make sense to me and emerged through years of practice and reflection.

If you are a leader of innovation, think about your own conceptual models. Consider where you might fit. Any conceptual framework will not fit reality perfectly, but it can at least give you a scaffolding to build on as you find your own way forward in your own unique context.

August 25, 2020

The World Does Not Rest On Your Shoulders

In my last two posts, I shared two hard truths about taking responsibility: The World Owes You Nothing and The Cavalry Ain’t Coming. I emphasized that there is no substitute for the hard, grinding work of creating change, and innovators should not look to the horizon for a miraculous rescue.

Today’s hard truth is almost an inversion of the last two: the world does not rest on your shoulders.

I squirm, writing that.

Of all these hard truths, that one might be the hardest for me. I cannot say I have fully internalized it. I am preaching to myself as much as to you.

My expectation of disaster

I was once Aircraft Commander for a C-17 mission supporting a Secretary of Defense visit to three South American countries. We were to shadow his business jet from airport to airport in case it had maintenance issues, and personally carry him and his entourage to an austere airfield the business jet could not reach. This was what military officers call a “no-fail” mission. The logistics were complex. We spent weeks coordinating details like passports, visas, landing fees, instrument approaches and departure procedures, and fuel services.

The individual who processed passports and visa requests at our base was one of the most difficult government employees I have ever met. He made so many mission-impacting mistakes and lost so much paperwork that we started a spreadsheet to track incidents. He was always acerbic and always denied responsibility. He could not be fired and we could not work around him.

Days before this no-fail mission–during my daily, paranoid checkups on his work–I learned he had mailed the entire crew’s passports to the wrong office, which meant we would have none of the visas needed to enter the three countries where SECDEF was traveling. I spent the next three days on the phone with embassies and agencies across Washington D.C. We worked out a convoluted plan that involved a forward-leaning bureaucrat (the hero we all need!) driving all over Washington D.C. to obtain visas, then hand-carrying passports to a base where we would be making a fuel stop en route to South America. We pulled it off–barely. Had it not been for our paranoid attention to detail and concerted effort to create a solution, we would have fumbled one of our most important missions of the year.

This is an especially egregious example, but I have had experiences like these over and over in my career. So many times when I have trusted the system to work, it let me down. Support agencies have lost my paperwork, forgotten to write my annual performance reports, nearly ruined my promotion boards, and screwed up geographic moves for me and my family.

The problems compounded when I started leading aircrews and teams. Every C-17 pilot can relate; the flight crew is the last line of defense in an incredibly complex orchestration of agencies that have a role in mission success. Aircraft Commanders spend a disproportionate amount of their energy monitoring this symphony and then swooping in to fix impending disasters: the passengers are late, the wrong cargo shows up to the jet, diplomatic clearances aren’t properly coordinated, headquarters planned your flight to a closed airfield. You quickly learn to expect disaster. You learn to trust no one but yourself and (usually) your crew.

This expectation occurs in a context where the vast Air Force mission enterprise is doing exactly what it was trained and built to do.

When you lead change, things gets even harder.

Now you are stretching the organization out of its familiar patterns and rituals. You are introducing new workflows and tools, trying new tasks and behaviors, attempting to use support functions in novel ways. Nobody is fully trained for this. Everyone is learning together–including you. Oversights, mistakes, and inadequate work are endemic. You are juggling a thousand details, and because you as the change-maker are carrying so much risk, one dropped ball could sink your entire effort.

Over the years, these experiences have left an indelible imprint on me.

There are very few people I trust completely.

Everything rests on my shoulders, I think.

And that belief is dangerous.

Life in the paradox

At first, this might seem to contradict my last two posts. Haven’t I been writing that leading innovation requires taking ultimate responsibility?

Yes. But.

It would be handy if a single set of principles could offer sure guidance through all the messy ambiguity of life. However, real life generally embodies paradoxes: two apparently irrreconcilable propositions that are both absolutely true. You must work hard but not overvalue work. You must strive for success but anticipate and make your peace with failure. You must be generous in relationships but also set boundaries. You must give your children sound instruction but also let them learn from their mistakes. A well-lived life entails constantly navigating these paradoxical tensions.

This is no different.

When you lead innovation, you must take ultimate responsibility for the outcomes you wish to achieve. You must learn to rely on your own resources, creativity, ingenuity, and hard work. You should not expect others to carry your burdens or swoop in to rescue you.

At the same time, however, you cannot carry this burden alone.

If you try, you will not last long.

Resolving the paradox

Creating change in entrenched systems is hard. Incredibly hard.

Hundreds or even thousands of people have labored for years to make the system what it is. The system is the emergent outcome of financial investments, sales histories, defeats, victories, legal battles, and untold expenditures of time and energy. Previous generations built this cathedral brick by brick, with all its majesty and all its imperfections. Intrapreneurs just as passionate as you put their blood, sweat, and tears into shaping, sanding, and polishing it to perfection.

And here you are. One person. Standing in defiance.

There is nobility in that. That is how any great change or creative work begins–in moments when, as Steinbeck wrote, “a kind of glory lights up the mind of a man.” An inspired leader has a fleeting glimpse of a different future, with no idea how to make it real in the face of such overwhelming odds, but takes the first step in faith anyway.

Now you are in the arena, and your adversary is so much stronger. The combined might of that vast system will be brought to bear on you.

This will not be a quick or easy battle. You will quickly realize that you must settle in for the long haul, that you need allies, that this one battle will likely unfold into a campaign lasting years–perhaps even generations.

You will need to fight tirelessly, but you will also need to manage your energy and your health. You cannot possibly comprehend all the million details that will be need to be resolved, nor the alignment of forces that will need to occur to make lasting change. You will also discover that althrough your basic intuitions might be right, your grasp of the details is incomplete or even profoundly wrong. Your ideas must evolve, often through rigorous testing and profound challenge.

To lead change, then, you need other people. You need a team. You need allies. You need to synchronize your efforts with many others who are fighting similar battles in other places. You might even need enemies.

You also need to recognize that by stepping forward in opposition, you are opening yourself to forces beyond your control. Think about Martin Luther nailing 95 theses to a church door, Rosa Parks refusing to give up a bus seat, or Billy Mitchell using an airplane to sink a Navy ship. The contexts were extremely different, but in each case, an individual picked a fight that would reverberate through the halls of power and ripple across vast swaths of society. These acts challenged institutions, cultures, ideologies, and norms. The reformers had no way of knowing precisely how incumbent forces would respond, but one thing was certain: the response would be big, and it would be beyond their ability to control.

Reform often requires surrender, then–not giving up, but yielding ultimate control to forces and processes far bigger than ourselves.

If we persist in believing that this burden falls entirely on our shoulders, we place impossible expectations on ourselves. We will be broken–either in one fatal blow, or through the accumulated weight of unmanageable challenges.

The hard challenge

Living with this tension is hard–and one of my biggest personal challenges.

The paradox plays out every day. In my various innovation projects, I have been the chief “vision owner” and have spent thousands of hours mastering complex implementation details. I believe my personal ownership of wide-ranging details is what makes me effective and allowed my previous initiatives to make it as far as they did.

At the same time, I place impossible expectations on myself. My time leading Uplift Aeronautics shattered my mental health, which set me on a long journey of soul-searching and healing. I approached Rogue Squadron with more wisdom and balance, and we built a stellar team and coalition, but I still repeatedly found myself stumbling under the burden. Especially as our team grew, I struggled every day with where to maintain personal control and where to surrender that control to forces outside myself. There was rarely a clear answer; it was all tradeoffs. I have entrusted control to others and watched disaster ensue; I have also entrusted control and watched colleagues achieve feats I never could have imagined.

Navigating the paradox is a deeply personal journey that every innovator must make. You are ultimately responsible, and yet the weight is not on your shoulders alone. It is your determination and hard work that will create change, but forces beyond your control are in play. You must be detail-minded and self-reliant but also trust and lean on a broader community.

Image taken from Apple’s classic 1984 ad –which, incidentally, was recently subject to a brilliant recreation by Epic Games as part of its legal battle with Apple.

August 21, 2020

Dogfights, AI, and Bureaucracy

The big Air Force news this morning is that an Artificial Intelligence algorithm easily defeated a human F-16 pilot in simulated aerial dogfighting in a 5-0 sweep. The three-day AlphaDogfight trials were hosted by DARPA.

I am not particularly surprised. I have never been a fighter pilot, but dogfighting–like many aspects of flying–strikes me as an exercise in precise energy management and control systems theory; the precise and timely application of proper control inputs will conserve energy and maximize the probability of ending up at the right time place at the right time. That is the kind of bounded task at which machine learning should excel (managing the complex, ambiguous, and open-ended environment in which dogfighting might occur is another story).

However, I have always worried about the ability of the DoD bureaucracy to manage AI algorithms. Our acquisition processes were designed for hardware; we spend years building, testing, certifying, and fielding a widget. Then we spend years sustaining it while we build the next version.

Software completely upended this paradigm, because in the modern world, software is released into production in the earliest stages of the lifecycle and new changes are released into production continuously–sometimes hundreds of times per day. Software obliterates the distinction between Research and Development (R&D) and Operations & Maintenance (O&M). It compresses requirements generation, design, building, testing, evaluation, and fielding, and sustainment into a tight circle rather than a linear process.

DoD has had severe struggles adapting to the world of software. A tireless assault by insurgent software factories–like Kessel Run, Space CAMP, the Defense Digital Service, Kobayashi Maru, Tron, BESPIN, and my own Rogue Squadron–has begun transforming the system. These organizations are making progress but it’s a bit like trying to steer the Titanic, and we all have scars. We certainly aren’t there yet; a lot of “agile” is still just agile BS. DoD rarely practices Continuous Integration and Delivery, and many DoD systems are still updated only intermittently–after new approvals processes–by handy-carrying memory sticks or even 1970s floppy disks.

AI algorithms strike me as an even harder challenge, because algorithms that continuously learn could literally change hundreds of time per second. If large parts of DoD still require lengthy approvals processes for new software versions, how on earth will we manage constantly evolving algorithms? Especially given how opaque and mysterious many algorithms are? One of the fundamental challenges with evaluating machine learning algorithms is that they are rarely explicable; results are achieved by manipulating parameter weights in models. They rarely rely on logic, heuristics, or features that can be articulated to mere mortals. They also have bizarre failure modes: they can be brittle, overfit to particular training sets, or trained on data that does not accurately represent the real world. This means that algorithms require human oversight, but DoD lacks the knowledge, skills, tools, and processes to manage AI effectively.

I am so concerned about this that I wrote a short story a few years ago, specifically to help DoD leaders understand the issues in play. In Fitness Function, bureaucratic inefficiencies throttle the vast potential of AI–and ensure overmatch by a near-peer competitor. If you are interested, you can read it online at CIMSEC or download a free copy.

Image courtesy of Breaking Defense

The Cavalry Ain’t Coming

In my last post, I shared a hard truth: the world owes you nothing . Today I continue the series with another, related hard truth that innovators must learn.

As a young Air Force officer, I constantly raged against the machine. So much felt broken. Over the years I learned to manage my anger (somewhat) and tried to focus on creating solutions, but that introduced a new problem: I did not have the requisite authority. All I could do was pin my hopes on senior ranks, and perhaps someday join those ranks myself. Maybe I could acquire the influence to make a difference.

When I was a Major, the Chief of Staff of the Air Force visited my SAASS class for a group discussion. This was a man I had followed throughout my career, admired, and even revered. Over and over again, he deflected our questions about the entrenched problems the Air Force faced. He insisted he was powerless to change them. At one point, in a misguided effort to offer encouragement, he said, “This is why we need you to study and learn, so you can tackle these problems.”

The bottom fell out of my universe.

I had been laboring up through the ranks so I could finally have enough influence to make a difference. Now I saw the lie behind the game: I had been living in a hamster wheel. Our most senior leaders felt just as trapped as I did. If the highest-ranking Air Force officer was looking to a new generation of Majors to solve problems beyond his control, we were doomed. The whole thing was a vicious circle.

That was a critical moment in my career when I embraced a hard truth: the cavalry wasn’t coming. No savior-general would step in and reverse our fortunes. Magical decrees would not deliver sweeping reform. We were all in this together, regardless of our rank. We had to find our own way out of this mess, with whatever resources were at our disposal.

It is the same in any organization, any government, any social institution, any athletic pursuit, or artistic endeavor. Whenever we face a monumental challenge, we desperately want rescue. We want to find the senior leader champion, the investor, the journalist, or the key influencer who will change everything.

But this is the hard reality: the cavalry ain’t coming.

It is on us.

Life is not a Deus Ex Machina

A deux ex machina is a plot device typically attributed to Greek theater. The playwright would ensnare his or her characters in ever-worse complications until all hope of resolution seemed lost. Then, at a critical moment, divine intervention would occur; human actors playing gods would be elevated or lowered onto the stage. The Latin phrase deux ex machina literally means “god from the machine.”

The device continues to drive many works of fiction. When all hope seems lost, the Cavalry rides into the rescue.

I think of Gandalf promising Aragorn, “Look to my coming on the first light of the fifth day.” The Battle of Helm’s Deep rages throughout the night, hope fades, and then in a moment of a desperate, final defiance Aragorn and Theoden ride out to meet the enemy. We expect a death worthy of legends, but at that very moment, Gandalf appears at the head of an army–which turns the tide of the battle.

If only life worked like that.

Occasionally it does, but only rarely.

The deus ex machina is a dangerous plot device that, if not carefully handled, leaves readers feeling cheated.* The best stories are those in which heroes take full responsibility for their actions and must find their own way out of their dilemmas. Think about Mark Watney and his colleagues in The Martian. Their every action introduces unforeseen consequences that ratchet up the stakes, but in the end, it is their ingenuity and teamwork that brings the story to a successful resolution. Stories like this satisfy us as readers but they also resonate with our own life experiences.

Chris Gardner–the man whose story was dramatized in The Pursuit of Happyness—described watching a Western with his mother when he was a child. As the film approached its climax the hero was alone, with no horse or sidekick, running low on ammunition. His eyes searched the horizon. He saw nothing but tumbleweed and cactus.

“See that,” Gardner’s mother told him. “The cavalry ain’t coming.”

She wanted Gardner to understand that the hero would have to save himself. Gardner says that the hero did indeed save himself, but:

his resolve and ingenuity did not kick in until he accepted that no cavalry had been sent to bail him out. He had to become his own cavalry.

He goes onto say that “the cavalry ain’t coming” is a state of mind and an attitude. It requires “taking stock of where you are, understanding how you got there, and then figuring out the steps necessary to get to where you want to be.”

(hat tip to Marelisa Fabrega, whose post on the same theme introduced me to this wonderful anecdote)

My own search for the cavalry

If you are leading change, founding a startup, or trying to create a great work of art, you must be attuned to this longing for rescue. Your alarm bells should sound any time you find yourself, as Gardner says, “gazing hopefully out to the horizon.”

When I founded and led the Syria Airlift Project, I was constantly hoping for rescue. I hoped to get on the radar of Jimmy Carter and Richard Branson. I pitched to the CEO of one of the biggest drone companies in North America. A team member spoke with Staffan de Mistura, the UN Special Envoy for Syria. We got our work in front of Samantha Power, the U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations. A colleague briefed the project to the Chief of Staff of the U.S. Air Force. In each case, I desperately hoped that the support of a high-level patron would change our fortunes. Speaking with these leaders was an important line of effort, but in retrospect, it was amazing how little tangible benefit any of these engagements brought us.

Nearly all of our growth came from modest, incremental steps forward. We would attend one conference and successfully recruit one volunteer. Our engagement with a CEO would yield a few thousand dollars worth of sponsored equipment and an ongoing relationship. A meeting with a politician would bring five new introductions, one of which brought up a remote opportunity of connecting with an aid organization in Jordan. Much of our time was spent relentlessly fighting for every single source of advantage. One advisor wisely told me that we needed to treat every single ally, partner, or donor–no matter how modest–as a million-dollar investor. Our hope of success rested with the accumulation of these small advantages.

My experience leading Rogue Squadron, an agile software development team in the Department of Defense, was similar. We had one deus ex machina when an early champion secured a large amount of funding, but even that introduced a ton of new complications to be solved. For the three years that followed, we worked tirelessly for every ounce of support. We interviewed up to 40 candidates for every open position. We spent months or even years courting other DoD organizations before they offered support. We spent a year tirelessly undoing a contracting mistake and writing our own replacement contract. Our battles were never-ending.

We are all in the same boat

My experience is not unique. If you are an entrepreneur founding a startup, your key currencies are funding and talent. Among your chief responsibilities are building and capitalizing a winning team, so you are constantly on the lookout for the individual people and the deals that will secure your future. It is all too easy to pin your hopes on a particular investor, a key customer, or a media event.

If you are an intrapreneur working inside a large organization, your key currency is influence. To succeed, you need to build a coalition of stakeholders who will help approve and execute your idea. It is tempting to pin all your hopes on a particular briefing to a particular leader. If I can just pitch to her, you think, everything will change. That can be true to an extent, but is sobering when you realize that your senior champion is just as entangled in red tape as you are. In most cases, your pitches will only yield incremental advantages. The responsibility still rests on your shoulders to stitch those little victories into a campaign plan that will yield success.

If you are an artist, nobody but you can do the hard work of creating a masterpiece–and then helping it succeed in a busy, distracted world. No publisher or publicist can substitute for your own relentless effort to create and promote excellent work that finds a loyal audience.

Even if you do receive a windfall of support in the form of a cavalry rescue, this will likely introduce as many new complications as it solves. Just ask any founder who lost control of their company to aggressive investors, or any government intrapreneur whose sleek idea was transformed into an unwieldy behemoth by institutional support.

The good news

Abandoning the hope of a cavalry rescue does not mean relinquishing the hope of success.

On the contrary, it means taking responsibility, using your creativity and imagination, and applying unceasing energy to the task before you. This mindset is really an extension of what I previously wrote, about getting over the idea that anyone owes you anything. Just as you should not plan on extensive support from within, you should not plan on rescue from without.

As you take responsibility, you find a few things:

You have more authority than you think. There is usually something you can do at your level–whether that’s writing a paper, planning an event, creating a mockup, or meeting with stakeholders to learn more about a need. Once you start, magic can happen.

Leaders are hungry for competent problem-solvers. Senior leaders are too busy to own execution of new ideas. They have even bigger problems than you do, and less time. So when an employee shows up with both vision and an ability to execute, leaders take notice. Finally an employee who can help solve their problems! This lays a foundation for a strong partnership that can multiply your chances of success.

Relentless execution becomes a habit. As you internalize the mindset of executing at your level, it gets easier. You intuitively take stock of the resources available and the opportunities at hand. Your default posture becomes one of preparedness and action, rather than passive acceptance.

Like-minded allies will find you. There are others like you. As you show responsibility and a commitment to action, you will find each other. You will help each other. Collaborations will emerge, ideas will be tested, and new opportunities will take shape.

You will enter a continuous learning loop. You don’t learn much when the cavalry rides in to save you, or a champion gives you everything you dreamed of. However, when you have to draw on your own resources, you struggle. You learn. You fight for every ounce of support, and if it’s not forthcoming, you ask you yourself why. Your ideas are ruthlessly tested. If they aren’t good enough, you feel pain. That learning might be more valuable than your wished-for rescue.

Take responsibility. Execute at your level. Learn to be your own cavalry. That is how hard things get done, whether you are a CEO or a day-one employee.

P.S. I actually loved this scene in The Two Towers. It is high fantasy, and sometimes a skilled writer can make the device work. Still, the point stands.

August 18, 2020

The World Owes You Nothing

One of the hardest lessons to learn as an innovator is that the world doesn’t owe you anything–even if you feel like it should.

This is more complex than “don’t act entitled.”

In most large organizations, a significant number of employees are happy to carry out business as usual. They file its reports, comply with its requirements, operate through its processes, and attend its scheduled meetings. They are, in other words, doing exactly what the organization has asked them to do. These people fulfill vital functions. However, carrying out routine instructions does not necessarily require a lot of imagination, creativity, or strenuous uphill boulder-pushing.

A smaller number of employees regularly identify inefficiencies in the organization’s programming or see opportunities to do better. Of those, only a subset can envision and articulate positive, actionable ways to improve. Only a fraction of those have the determination and stamina to actually execute. Those are the true intrapreneurs.

If you are in this subset–a rare leader of change–then you have embraced a sacred and difficult responsibility. You will spend far more energy than many of your peers, will fight the bureaucracy at every turn, will take personal and professional risk, and will go above and beyond your formal job responsibilities without compensation. You will do all this not for yourself, but to create positive change in an organization you believe in.

The organization absolutely should owe you something. It should owe you support, respect, resources, and help clearing blockers.

Your desire for support isn’t necessarily about self-interest or ego satisfaction; it is about your legitimate and rightful need for assistance on your dangerous, difficult quest to improve the organization. The ideal organization would identify its most promising intrapreneurs, promote them, and equip them with the tools needed to create positive change.

The hard truth

Unfortunately, we do not live in a perfect world.

The minute we expect our organizations to give us the assistance we think we deserve, we will be disappointed.

There are several reasons why organizations do not give intrapreneurs what they hope for:

Organizations are programmed for stability, not change. This tension is built into the universe; to grow, organizations need to standardize processes. That is true even of the most innovative organizations, which is why scaling innovation organizations is so hard. As a changemaker, you will always be cutting against the grain. By definition, you are operating outside (or trying to change) the processes that you wish were helping you.

Resources are always scarce. Even if your ideas are brilliant, your organization is juggling numerous priorities with limited resources. One of the frustrations of being a leader is that you know you are underresourcing critical needs, but you have so many critical needs that you have no choice.

It is difficult to identify the best innovators (and innovations) a priori. Even if you have a proven track record, it is hard for your bosses to know whether your idea deserves more resourcing. Many “innovators” offer more heat than light, and even the best innovators have mixed track records. I have suggested or implemented dozens of improvements in my career. Some were knockout successes, some failed, some proved to be lousy ideas, and many had mixed results. It is often a good leadership tactic to place small bets at first, then scale resourcing as an idea proves its value.

Many organizations are broken. It is sad but true. Many organizations are so dysfunctional that it is simply foolish to expect them to do the right thing. One clear sign of brokenness is when all stakeholders want to execute an idea but cannot find a way. At that point, the “bureaucracy” has taken on a life of its own, beyond anyone’s control.

The mindset shift

Regardless of why your organization isn’t supporting you, don’t dwell on it.

Reframe. Start with the idea that your organization is a blank slate where nobody owes anyone anything. You are nobody special; you are just one voice in a sea of voices. Your ideas exist in a cloud of other ideas. The responsibility for differentiating yourself, building support for your ideas, and executing change rests primarily on your shoulders. Any help you receive is a generous and unexpected gift for which you can express gratitude.

Adopting this kind of thinking has a few benefits.

It keeps you humble. All of struggle to tame our egos, and our legitimate need for support can quickly bleed into an egocentric sense of entitlement. The premise that the world owes us nothing continually nudges us back.

It emphasizes your agency, directing your attention to things under your control. Any mental or emotional energy spent wishing things were different is unproductive. Wishful thinking does not create change, generate resources, or advance your goals. Far better to allocate your precious attention to factors under your control.

It replaces negative emotions with positive ones. Disappointment, frustration, outrage, bitterness, and hurt will erode your health and happiness. These feelings inevitably arise, but if you can develop a habit of capturing and reframing them, you will be happier and have more productive energy. If the world owes you nothing, then any good that comes your way–no matter how feeble–is something to be grateful for. A default posture of gratitude will also help you identify opportunities in any situation.

It positions you for healthier relationships. The emotions you cultivate will spill over into your working relationships. If you are stressed or angry, those emotions will tinge everything (don’t ask me how I know). On the other hand if you are consistently positive, grateful, and optimistic, you will bring vital energy into relationships. Those same emotions will also spill over into your relationships outside of work. Incidentally, if you bring positive energy into working relationships, you are actually more likely to generate the support you need.

The case of entrepreneurs

The same principle holds true for entrepreneurs working outside the constraints of an existing organization. You founded your startup, wrote your novel, or created a social action campaign because you believe you have a winning idea–and maybe you do. However, for your idea to take flight, you will need a tremendous amount of support from other stakeholders. These might be customers, investors, regulators, volunteers, supporters, or other allies. Entrepreneurs only rarely find the tidal wave of support they are hoping for. Most have to relentlessly fight for every last bit of support.

This brings you to the same inner crossroads. On the one hand, you can harbor resentment or frustration that more support has not materialized. On the other hand, you can start with the premise that the world owes you and your idea nothing. You can build on that foundation, take responsibility, and act to grow the support you need.

Conclusion

Mental reframing does not change your material situation. You still want support, and are still getting less than you hoped for.

However, your attitude makes all the difference in the world.

If you believe the world owes you something, you will ruminate over your hurt and anger. These negative emotions will sap your energy without doing anything to improve your situation, all while potentially damaging key relationships.

On the other hand, starting with the premise that the world owes you nothing lays a foundation for action and growth. You quickly push past negative emotions into the realm of action. You take responsibility for your situation, search out ways to improve it, and take steps to grow the support you need. You direct your energy into productive steps, and along the way, you find abundant opportunities to be grateful.

Photo by Andrew Neel on Unsplash

August 14, 2020

Finding Your Temple

“Now the general who wins a battle makes many calculations in his temple ere the battle is fought.” – Sun Tzu

Effective leaders must spend time in the temple.

Too many leaders live moment-to-moment in the battlefield grind: leading employees, triple-checking positions, monitoring logistics, compulsively checking the news or consuming a dizzying feed of blogs, podcasts, and reports. New taskers bombard them hourly. Subordinates line up at the door with problems or questions. The Urgent swamps the Important. We expend 100% of our energy just holding things together. Maybe more. We burn out without moving the needle.

Not Sun Tzu.

Sun Tzu tells us that an effective leader retreats into silence and solitude. He hides himself among the walls of smooth, cool stone. Tree-dappled sunlight pours through high arched windows, into an empty vaulted space that draws his eyes and heart up into the heavens. The general drinks deep draughts of this rich silence in order to replenish his soul.

Sun Tzu’s general knows that he can do more for his army or nation by withdrawing from the relentless daily grind in order to think. In that white space of interior silence, he can assess patterns, consider whether all that expended energy will amount to a victory or something else, plan major course changes that nobody in the ranks has time to even imagine. It is in that quiet sanctum that a general can look up from the tactical and imagine entirely different futures.

In his temple a general also finds the space to heal her own soul, thoughtfully consider the fundamentals that matter most, and lay plans for the future. She emerges revitalized, strong, clear-minded, at peace with herself and the world.

Why you need a temple

If you are an intrapreneur who seeks to lead change you must learn to spend time in the temple, or you will be destroyed. That is because your driving purpose is to work against a machine vastly larger and more powerful than yourself.

Your breakdown not happen immediately.

When things are going swimmingly, you will feel electrified and alive and ready to take on the world. The MVP is coming together nicely. Your leaders and stakeholders are delighted. You are failing fast, failing forward, failing often. You are learning. You are like Captain Kirk in his captain’s chair, passing cool orders to your team, watching them execute, feeling the thrill of leadership and intoxicated with the potential of what your new initiative might become.