Mark D. Jacobsen's Blog, page 2

June 30, 2024

Day 12: If You Want Infinite Variety, Stay With One Place

In her profound defense of monogamy, Joni Mitchell cites a striking quote from an Esquire magazine article: “If you want endless repetition, see a lot of different people. If you want infinite variety, stay with one.” Mitchell writes, “What happens when you date is you run all your best moves and tell all your best stories—and in a way, that routine is a method for falling in love with yourself over and over. You can’t do that with a longtime mate because he knows all that old material. With a long relationship, things die then are rekindled, and that shared process of rebirth deepens the love.”

That feels wise and true, both in relationships and other domains of life.

I encountered the quote while immersed in books about nature, place, and belonging, partly to prepare for my trip and partly because I’m weaving this thread into my next book. It’s impossible to separate belonging from place, but in our modern world, we are so disconnected from place that we don’t even comprehend our disconnection.

I can’t help but think about how Joni Mitchell’s wisdom applies to place.

If you want endless repetition, see a lot of different places. If you want infinite variety, stay with one.

What would it mean, if that were true?

It’s a salient question, as we give up Yosemite Valley in favor of returning to Truckee.

—When it comes to place, I have lived the spectrum of faithful exclusiveness to rampant promiscuity.

I spent the promiscuous years flying C-17A Globemaster III cargo planes around the world for the United States Air Force. Most trips lasted two to three weeks. We departed Washington state, typically stopped on the east coast for gas and cargo, and then ping-ponged around Europe, Asia, and the Middle East until it was time to come home. Most of my flying was 2004 to 2008, at the height of the Afghanistan and Iraq wars. Both countries had the gravitational attraction of black holes; we were lucky to fly anywhere else.

Still, we did travel. I flew to 21 countries in those four years. I spent dozens of nights in Germany and Spain, both major hubs for U.S. airlift at the time. My first deployment—a hardship tour, I know—was to Frankfurt. These were rewarding but exhausting years. Missions typically lasted twenty to thirty hours, hotel to hotel. I awoke in a different city and time zone each night. My body lost its circadian rhythm entirely. I usually slept in blocks of four to six hours, sometimes at night, sometimes in daylight, always hoping they would set me up properly for my next flight. Sometimes they did; when they didn’t, flights were excruciating. Occasionally my body crashed; I once slept 20 hours straight.

During these years, I practically lived on the road. I tallied 230 days away from home one year. At first I felt the thrill of adventure, but over time, I felt a dreary sameness about every new location I visited. Each overseas military base offered different versions of the same features: a commissary, a base exchange, restaurants, and a market where local merchants sold souvenirs and hand-made goods. Cities without bases were marginally more interesting. We stayed in the best hotels the government would pay for, picked famous restaurants that sometimes offered neatly-packaged cultural experiences, and piled into crew vans to hit the most famous tourist attractions. In Ghana, we went to a modest museum and wandered through a local market marveling at skinned animals hanging from hooks in the summer heat. In Athens, we squeezed in a trip to the Parthenon. Full days off were rare, but we took advantage of them, driving hours in rental cars to Rothenberg or Brussels.

I’m grateful for all these experiences, and mindful that many people would do anything to have similar opportunities. But over time, such travel wears thin. My travels were a succession of one-night stands, novel and thrilling at first, but then dreary in their unfulfilling repetition. With each departure, I left nothing but a vacant hotel room.

—I have had richer travel experiences, of course, typically while off-duty. My wife and I favored quiet getaways nestled in nature: the Olympic Peninsula, Mendocino, Point Reyes. Two years in Jordan gave us the chance to truly learn a place. We left with memories, friends, and a new language. We also traveled extensively to other countries in the Middle East, which was wonderful for learning the region but also left me with that weary morning-after feeling from my whirlwind C-17 days.

During these years, two things taught me that a much deeper sense of embeddedness in place might be possible. First, we saw and experienced how deeply rooted Jordanians and Palestinians were in their land. Generations lived together. They knew their lineage, their ancestral homes, particular houses and olive groves.

Second, I began to encounter masterful books by authors who knew particular places and landscapes with astonishing intimacy. These books were an acquired taste—protracted meditations that entailed sitting still, observing, listening. They demanded of the reader the same qualities that the authors internalized. A few early influences spring to mind, like Annie Dillard‘s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, inspired by a year in Virginia’s Roanoke Valley, and Dakota by Kathleen Norris.

As I’ve gotten older, my reading tastes have shifted further in this direction. Mary Oliver‘s poetry and essays, crystallizing the beauty and wonder of the forests she roamed; Wendell Berry‘s works, doing the same for rural America and for Kentucky in particular; Barry Lopez’s 500-page Arctic Dreams. In Desert Solitaire, another work of meditation on landscape, Edward Abbey writes, “If a man knew enough he could write a whole book about the juniper tree. Not juniper trees in general but that one particular juniper tree which grows from a ledge of naked sandstone near the old entrance to Arches National Monument.” Those dazzling lines express the same love that Joni Mitchell evokes: the infinite variety of a single thing.

—I have been writing this post off-and-on since my trip began, not sure where it would fit. Now we are returning to Truckee. One place, chosen over a multitude of places. It’s a pleasure to wake up in our meadow—I think of it as our meadow now—and make our morning drive to the Dark Horse Coffee Roastery. Hannah, who has a long background managing coffee shops, strikes up a conversation with the head roaster. He joins us at our table for a few minutes. Our first thread of human connection, weaving us into the tapestry of this place. Hannah texts a friend who lives nearby. We make plans for dinner and a hike together the following weekend. Another thread of connection.

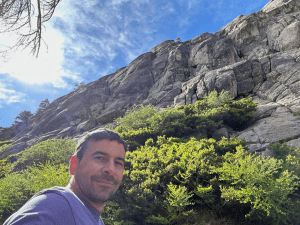

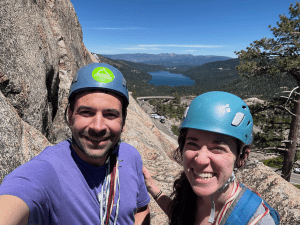

After our morning writing session, we drive to Donner Summit. I find it harder and harder to write about these climbs because the novel has quickly become routine.

I’ve read that the lives of highly successful people often look rather boring, because they have structured their existence around the disciplined pursuit of their craft. Our afternoons at Donner Summit are beginning to have that feel. We park in the same gravel turnaround, put on the same harnesses, equip ourselves with the same gear, and make the same hike to the base of the same wall. I know most of the climbs on this face now: the route names, the cracks, the belay spots, the notches where one can easily climb over the imposing roof atop the slab. I enjoy this intimate familiarity. We are building a relationship with this place.

We climb Kindergarten Crack again, repeating a climb we made before our adventure in Yosemite. It’s not the masterful performance I’m hoping for. My awareness seems dulled by a brain fog, and I need to hang on the rope to rest at the same spot I did last time; it’s not a hard move but it feels intimidating, and I wear myself out summoning the courage to commit to it. Later, I struggle to find good placements to build a belay anchor.

Our progress is painfully slow. But this is the nature of building a real relationship: forward progress through ups and downs. The intoxicating novelty has worn off, and now we’re just working, trying things, learning, discussing what we can do better.

—All of this holds lessons for my eventual homecoming to Montgomery, Alabama. It’s not the place I would have chosen for myself, but it’s the place I have. I haven’t met many Montgomery residents who love the place, even those who’ve lived there for decades. We swap stories about the unlikely ways we arrived in the city, and we all marvel at the fact we’re still there. Somehow, life pinned us in place. Although we daydream of moving elsewhere—and maybe someday we will—a deep, patient love flows like a subterranean river. In a city where every step forward seems matched by a step back, we each feel a quiet calling to make the city better than it would otherwise be.

I keep reading authors of particular places because they teach me how to love a place: how to see, how to learn the names of things, how to weave together the history, geography, biology, and sociology of a place into a coherent and meaningful understanding.

We will likely only be in Truckee for a few more days, but our return is giving me the opportunity to practice faithfulness to a place. The disappointment I felt yesterday at leaving Yosemite Valley has faded. I’m happy we’re here.

June 29, 2024

Day 11: The Anguish of Our Finitude

Yesterday, aboard the bus shuttling tourists from the parking lot to the Mariposa Grove, a big red LED display display the date and time. I’d barely looked at a calendar since our trip began. The date startled me. It struck me, all at once, that our trip was half over.

That thought has sat heavy with me since then. Twenty-four days of unhurried time, between jobs, with no major commitments hanging over me, is an incredible gift. When we set out 11 days ago, time felt infinite. My ambitions are always sweeping, and I had a long list of achievements I hoped to realize: daily blogging, finishing a draft of my book, leading my first multi-pitch climbs, climbing some classics in Yosemite Valley, and then climbing the three most famous peaks in Tuolumne Meadows. All of that, of course, would be in addition to lazy afternoons reading in alpine meadows or by quiet rivers, spending time with Hannah, and showing Sam around Yosemite Valley.

Now, for the first time, I feel the rush of time. I’m on a clock. With just 11 days before driving back to Idaho to drop off the van and catch our flight, I need to make choices, and those choices entail tradeoffs. I cannot do everything. I cannot be careless or wasteful with the rushing hours. Even here, on a timeful vacation, Hannah and I must make choices about the life we want, the way we want to be in the world.

—Early in our fledgling relationship, Hannah and I read Irvin Yalom’s Existential Psychology, a doorstop book and foundational text from an earlier era. Every morning we met at Prevail Coffee to discuss Yalom’s exploration of four existential dilemmas all human beings face: death, freedom, isolation, and meaninglesness. The usual light fare for an early dating relationship.

Yalom believed that “death anxiety” lay at the heart of human experience. He writes, “Death anxiety is the mother of all religions, which, in one way or another, attempt to temper the anguish of our finitude.” In his book, Yalom traces this anxiety through every stage of human development, from infancy to old age.

At first, I was skeptical about the grip of death anxiety on my life. I don’t want to die anytime soon, and the risk weighs heavily on me every time I rock climb, but I also don’t have the suffocating fear of death that many people seem to. Perhaps that is one of climbing’s unusual gifts: it keeps an awareness of mortality front and center, in the purifying light, instead of leaving it to skulk in the shadows.

But as the book went on, Yalom made his case that death anxiety isn’t always explicit. Our deepest fear is not necessarily of dying, but of finitude, and this fear manifests in ways that seemingly have little to do with death. Ambition is one manifestation that resonates deeply. I feel an unquenchable thirst to learn, create, grow, achieve. I want my life to count for something, and I can’t help but measure its worth by tallying the things I’ve done and made.

My midlife passage, which I described in Eating Glass, included a painful reckoning with this deeply-rooted impulse. When I don’t achieve, who am I? When all becomes still, what is my worth? In what way has my fierce ambition blinded me to other sources of goodness, beauty, and worth in my life? I emerged from that self-confrontation a little bit wiser, more settled in spirit, and more attuned to the centrality of relationships and simple pleasures, but I still grapple daily with ambition’s role in my life. A life of desperate grasping after achievement leads to misery; on the other hand, healthy ambition plays a constructive role in fueling personal growth and our contributions to the world.

Now, in the heart of this vacation, I’m grappling with my finitude. My inability to do and become everything that I once hoped.

—The day starts out rough. We are camped at an RV park outside in Fresno. The evening heat was so severe that we couldn’t cool the van below 80, and the stove malfunctioned because of a perceived temperature error. We only slept an hour or two in the stifling heat.

We wake at 5am, drive Sam to the airport, then drive straight back to the RV park to sleep a couple more hours.

Once we are up for good, we drive to an Urgent Care clinic. We have survived a week of rigorous rock climbing and hiking without serious injury, but a minor scrape on Hannah’s finger—obtained while fishing cams out of cracks—has become infected. Half her finger is swollen white and pink. Fortunately, the doctor sees her quickly and prescribes antibiotics.

Our itinerary up to this point was well-established, governed by Sam’s flights and our days allocated to Yosemite. Now that Sam has departed, Hannah and I are on our own. We can go anywhere.

This leads to the most difficult decision of our trip: leaving Yosemite Valley behind. Before our trip, I had imagined wandering into Camp 4, the legendary focal point of Yosemite’s climbing scene, and finding experienced partners who could lead us up some of Yosemite’s classic climbs. I hopefully packed an extra-long rope, ascenders, ladder aiders, and other gear I’d never needed before. With imagination, determination, and the right mentor, we could make a leap forward in our climbing ability, tackling epic climbs I never would have dared to think possible.

It’s hard, letting that vision go, but we have to make choices. The crowds, traffic, and heat in Yosemite have been getting to us, and we’ve missed peak climbing season. But we both loved Truckee: the cool clean air, the milder temperatures, our cozy coffee shop mornings, the climbing at Donner Summit that is right at the edge of our growing abilities. Until this morning we had never considered going back—there were so many new places I wanted to explore—but Hannah and I agree it’s the right move.

This is one of life’s many tradeoffs: exploring widely, or settling deep into a place, paying ever-closer attention to its offerings, and internalizing its rhythms.

This decision also involves an important tradeoff related to our climbing. My vision for Yosemite entailed following on routes: finding an experienced partner to guide us up climbs that exceeded our own abilities. There is nothing wrong with this; I’ve climbed with more experienced partners before, taken classes, and had wonderful experience following guides up the Grand Teton and Looking Glass. However, returning to Truckee will demand something harder: I will lead the climbs, which means operating at the fringe of my comfort zone, pushing myself in challenging new situations, and gaining the skills and confidence to lead progressively harder climbs. The climbs won’t be as epic as those in Yosemite, but I will really, truly be learning.

This is the long, slow, disciplined path to mastery. When we return to Yosemite someday, it will be with real skills.

—We spend the rest of the day driving. A major construction project has begun on I-80, and we hit four major slowdowns. We have no choice but to take it in stride.

Returning to Truckee feels like coming home. I’ve stored coordinates for our favorite campsites, so dispersed camping has become easy and routine. Our favorite meadow is occupied, but we settle in a secluded dirt turnout not much farther.

We are back. We cook dinner, prep the van for the coming night, and drift peacefully to sleep beneath familiar trees and distant mountain peaks.

June 28, 2024

Day 10: Rest at Sentinel Dome and Mariposa Grove

The day after our almost-Half Dome hike, we are tired and sore. It is Sunday. A day of rest.

I want to make the day meaningful for Sam, given his short time in California, but we agree not to return to the Yosemite Valley floor. We’re ready to be away from the traffic and the crowds. We also don’t have the energy for any big adventures. Instead, we decide to wind our way up out of the valley on Highway 41, back towards Fresno.

We do a short hike up Sentinel Dome, which is the best reward-to-effort hike in Yosemite Valley. At only 2.2 miles and 500 feet of elevation gain, it nonetheless offers a 360-degree panoramic view of Yosemite Valley. It is the perfect recovery hike to stretch out our sore muscles without overdoing it.

Afterwards, we visit the Mariposa Grove of Giant Sequoias. The more one knows, the more one sees. I keep trying to get smarter on forest ecosystems—with novels like Richard Powers’ The Overstory and nonfiction books like Peter Wohlleben’s The Hidden Life of Trees—but I can’t seem to hold onto the details. They flow right through me like water, and I find myself simply marveling at big pretty trees like everyone else.

Developing the eyes to truly see a place like this is a lifelong effort, requiring extensive time and patience. The forest won’t yield its secrets on a quick drive-by. On my way out, the sequoias challenge me to keep reading, learning, looking, listening. I will see more next time.

In the evening we stay at a RV campground, where we do laundry, take well-earned showers, and watch Valley Uprising, the best single documentary about Yosemite’s climbing history.

And that is all for today, a day of rest.

June 27, 2024

Day 9: Half Dome (Almost)

Yosemite’s Half Dome might be the most iconic hike in the United States. This soaring granite batholith, which is second only to El Capitan on Yosemite’s impressive skyline, looks as if a divine scimitar has cleaved it in half; its southeast side slopes up to a summit like any other dome, but its northwest face is a sheer vertical wall that plunges back to the valley floor. Half Dome rouses the imagination and practically begs to be climbed. George G. Anderson first ascended it in 1875, barefoot and without modern climbing equipment, by drilling holes in the granite and placing iron spikes. Over the decades, those holes evolved into a set of cables that park rangers raise every spring to help day hikers clamber up the final 400 feet to the summit.

Ascending the Half Dome cables to the summit is an intimidating lifetime achievement for many hikers, but it takes tremendous effort just to get there. AllTrails clocks the roundtrip trail at 16.5 miles, with 5,305 feet of elevation gain. Even without the cables, this would be the hardest hike I’ve ever done, excepting a 23-mile up-and-down of Pike’s Peak when I was 25 years younger.

This is the one must-do hike during Sam’s visit.

—Unfortunately, Half Dome’s reputation entices more hikers than can safely ascend and descend the precarious cables. In 2010, Yosemite began requiring permits, which are assigned via lottery. The park issues only 300 permits per day. I’ve read that during peak seasons the probability of winning the lottery is around 15%.

We only have two full days in the park, Saturday and Sunday, the hardest days to win the lottery. Nonetheless, we try. Hannah, Sam and I each dutifully pay $10 to enter Saturday’s lottery. When none of us win, we try again for Sunday. No luck.

The summit is out, then. That’s unfortunate, but it doesn’t deter us. We’ll do as much of this hike as we can. I hiked the first three miles of this trail several years ago, with my family. The twin waterfalls, Vernal and Nevada Falls, make this a world-class hike even without Half Dome.

—We get a later start than I hoped, but since we’re not summiting, I don’t feel rushed. When we arrive on the valley floor, we encounter our first setback: all the roads near the trailhead are closed for construction. We drive to Yosemite Village, two miles away. Our plan is to catch the purple shuttle back to Curry Village, but when we arrive at the bus stop with our daypacks and trekking poles, we learn that the purple line is shut down. Our options are to take the green shuttle the long way around, requiring 50 minutes, or walk. I’m a little shocked at what feels like disastrous logistics planning in support of the construction; somehow, I expected park management to be as pristine as the wilderness.

We opt to walk, which means our 16.5 mile hike has just become 20.

—The trailhead is located on the far side of a footbridge that crosses the Merced River, which we’ll be following upwards for most of the day. The trail is initially paved to facilitate the throngs of hikers, but it also climbs steeply, as if resolved to shake as many of them loose as quickly as possible. Many turn around at the first scenic overlook, beneath Vernal Falls. After that the crowds begin to thin, and the trail turns to dirt.

The diversity of tourists here makes a striking and happy contrast to Truckee. Nobody likes crowds of tourists, but I’m legitimately happy to see people of all shapes, sizes, and skin color enjoying Yosemite. We hear a dozen languages. Elderly people and small children share the path with intrepid hikers outfitted with cutting-edge gear. I’m not sure why they flock here and not places like Truckee; Yosemite isn’t any less expensive. Possibly it’s just awareness; Yosemite is legendary, while most people have probably never heard of places Truckee or Yosemite’s lesser-known but equally gorgeous sibling, King’s Canyon.

I’m impressed by how many people continue the hike past the overlook. We soon reach the trail’s most spectacular stretch, steep stone stairs winding past Vernal Falls. My daughter remembers these stairs with fear. They feel more dangerous than they are, a fleeting brush with mortality, which left a lasting impression. A refreshing spray hangs in the air, cooling our bodies and wetting the stone. Bright rainbows twist and play at every angle.

At the top of the falls, hikers warm themselves and eat snacks on the bright granite. The squirrels are hopelessly domesticated, fat and fearless. We know better than to feed the wildlife, but Hannah feeds them anyways; they’re already ruined.

—From Vernal Falls, it isn’t much more of a hike to Nevada Falls. We make another steep climb, this time out of the spray, to a spectacular overlook. A footbridge crosses the Merced, right where it hurls itself down the steep cliffside with unimaginable force. I look for a sign I remember, which warned tourists, “If you go over the falls, you will die.” I don’t see it. Maybe the park service’s refreshing candor has fallen out of fashion. That’s a pity; I’ve read that the leading cause of death in Yosemite is tourists falling in the river from this trail. That doesn’t surprise me, given the number of people I’ve seen jumping over guardrails for selfies.

The upper reaches of the falls is where my family and I turned around before. It feels like a natural ending place, flat, expansive, with a feeling of summiting.

It’s hard to believe we’re only halfway, measured by both distance and elevation. We’re tired. I’m concerned about Hannah, who has never done anything this strenuous. She’s been strong and consistent thus far, but sooner or later, she’ll hit a wall. And Sam, for all his hiking prowess, has little experience with hikes this long or at such high elevation. His hydration consists mostly of Mountain Dew, his lifelong vice of choice, with occasional gulps of water at my insistence.

We take our time eating lunch. We take naps. I still feel unrushed. We have all day.

—The next stretch of trail is hard. It gets harder, and then it gets miserable.

The majestic views of Yosemite Valley, and the refreshing waterfalls, are gone. We hike a long flat stretch of forest trail, coming around Half Dome from the back side. Then the ascent starts. We have 2,000 feet to gain this way, trudging up meandering forest switchbacks. Everything hurts. Our prolonged rest gave our muscles time to seize up.

Our breaks become more and more frequent. I ignore mileage but check my watch altimeter every minute or two. We need to gain 2000 feet but are only ascending 50 to 75 feet between breaks. Time flows by. At first I insist we can take our time, saying we can rest as often as needed. But as the afternoon rolls past, I start to watch the clock. I’m meticulous about safety, but of all things, I forgot to pack the headlamps. Sunset will bring a precipitous drop of temperatures and then absolute darkness. We discuss options and turnaround criteria.

Hannah gradually approaches her limit. Eventually, an hour before our hard turnaround time, she makes the decision to wait on the trailside while Sam and I finish the hike. Sam and I forge ahead. I’m still checking my altimeter. We can’t climb the Half Dome cables without a permit, but we plan to climb the subdome. Not long after we part ways from Hannah, we break into the open and see Half Dome and the subdome looming above us. I’m still wary of time. The subdome looks brutal in its own right, with 400 feet of elevation gain on steep switchbacks.

And then, suddenly, we’re at an end. At the base of the subdome, a sign warns that permits are required to go further. That’s it. We’re done, 400 feet lower than expected. There isn’t anything to do; I’m not interested in defying the rules. Yosemite’s rangers have seen it all, and I don’t expect they’ll have any qualms about hitting us with the advertised $280 fine.

It’s disappointing to be this close, watching those little toy figures above us inching their way up the cables to the summit. But we’ve done what we can. Maybe someday we’ll return.

—Over the years, I’ve learned that I never need to save much for the descent. Descending takes care of itself. Gravity does most of the work. I only need a little water, and no food. The main challenges are knee pain and blisters. Still, I’m not sure if the same will hold true for Sam and Hannah.

The descent is mostly monotonous trudging. I’m amazed how long the trail goes, how much ground we covered on the way up. I didn’t realize.

We stop for water at Little Yosemite campground, near the top of the waterfalls. The moment Sam stops, he gets severe cramps and feels nauseated. Dehydration is almost certainly a factor. We force him to drink water, and this time he acknowledges that would be a good idea.

Then we continue on. Somewhere along the way, the sun disappears behind Yosemite’s tall granite walls. It gets cooler. Hours pass, and still the trail goes on.

When we reach the valley floor—the supposed end of our hike—we still have to find our way those two miles back to our car. We walk a mile to Curry Village, then mercifully catch a green line shuttle direct to Yosemite Village.

—Outdoor enthusiasts talk about Type 1 vs Type 2 fun. Type 1 fun is “enjoyable while it’s happening.” Type 2 fun “is miserable while it’s happening, but fun in retrospect.” (There is also Type 3 fun, which isn’t actually fun at all, even in retrospect)

This was good old-fashioned Type 2 fun. For someone without much experience hiking, Hannah’s performance was incredible. Sam is happy. By the end of the hike, I never want to hike again. In a few days, I’ll be eager to go again.

June 26, 2024

Day 8: Yosemite and Friends

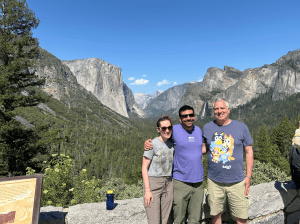

We wake early at the Love’s truck stop, drink coffee, and then drive to Fresno Yosemite International Airport to pick up my friend Sam. Our journey is entering a new phase.

Sam and I have been friends for more than 25 years, since I began attending a church youth group he helped lead. After I graduated, our mentoring relationship evolved into a friendship. We corresponded via lengthy emails, and on my visits home from the Air Force Academy we took hours-long walks around the parks and beaches north of Seattle. We could talk for hours about anything and everything. I was drawn to his intellectual curiosity, encyclopedic knowledge, and quirky sense of humor. We accompanied each other through major life events like marriage and the births of our children. We also accompanied each other through many shared interests, like Antarctica and Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s The Lady of Shalott.

We still correspond almost daily, although we’ve shifted from emails to lengthy asynchronous voice recordings in which we recount the books we’re reading, the outdoor adventures we’re undertaking, or the ups and downs of our lives.

Sam loves the outdoors and hiking, but his work and family commitments have kept him in the greater Seattle area for most of his life. He has developed an extraordinary intimacy with the stretch between Edmonds and Lynnwood; he knows every beautiful spot for a quick walk of any duration, every amusing piece of graffiti, and every arcane bit of urban lore. He has also adopted a disciplined but flexible approach to exploring the Cascade and Olympic mountain ranges, ticking off every notable hike as trail conditions and weather allow.

The first time I visited Yosemite Valley, I thought “Sam would love this.” We made a tentative plan for summer of 2020, but the pandemic upended that. Now, finally, it’s time.

—This entire trip is an experiment in a different way of living. For as long as I can remember, I’ve felt like an awkward composite of two selves: the Air Force pilot-technologist-entrepreneur and the spiritual writer on a lifelong pilgrimage. For these three weeks, I’ve resolved to give the latter free rein. In this seam between major chapters, I have the opportunity to be someone new, to live a different kind of life, to test out possibilities I might cultivate later.

Trying to design a dream life is an illuminating exercise. In 8th grade, my English teacher tasked us with describing a dream “pod” in which we might like to live. Much later, while reading a book about healing from relationship wounds, I encountered a similar exercise that entailed envisioning a dream house. It was a way of using creativity to circumvent reason, to get in touch with deeper impulses.

My imaginative dream life has stayed remarkably consistent over the years, and takes the form of what I call The Forest House. I sit outside this remote mountain cabin in the mornings, writing and meditating and watching the deer go by. In the early afternoon I go for long walks or other outdoor adventures. These long, slow days satisfy my deep need for solitude and meaningful, cerebral, focused work.

But in the evenings, this solitude is transformed. My dream life is, as the poet David Whyte calls it, a well peopled solitude. I light candles and switch on the party lights, casting my patio on a warm yellow light. My forest house looks like a Thomas Kincaid painting. Friends drop by. I uncork a bottle of wine. We talk for hours, pausing to grab blankets when a chill settles. When the cold becomes intolerable, we migrate indoors, light a fire, and pour more wine. In the wee hours of the morning, my guests slip away one by one, leaving me to the next morning’s solitude.

Friendship needs to be a pillar of the well-lived life. It is in dangerously short supply today, especially for men. This is one reason why my daydreams of escape into the mountains will never entirely satisfy. I want a life rooted not just in good places, but among good people. Even Thoreau, who we imagine living alone at Walden Pond, valued friendships, entertained visitors, and didn’t dwell far from human society. One commenter suggests he was a bit like “a child pitching a tent in his parents’ backyard.”

So after a week of idyllic solitude, Hannah and I are glad Sam can join us. I’m eager to share Yosemite Valley with a friend.

—It doesn’t take long for reality to rear its ugly head, when we hit a 1.5-hour traffic jam entering Yosemite’s south gate. I try to keep my irritation in check. At least the conversation is good, as we catch up on the months since we last saw Sam in Washington state.

Then we’re through the entrance and on our way. We pass through Yosemite’s famous tunnel and are rewarded with the sudden, overwhelming spectacle of the entire valley: El Capitan looming over the Valley floor, Half Dome peeking out behind Glacier Point in the distance, Bridalveil Falls pouring unfathomable volumes of snowmelt into the thick trees below. Sam snaps a photo that, in black and white, looks uncannily like an Ansel Adams. Amazing, the gifts modern technology bestows on us. The Tunnel View parking lot is packed, but it’s hard to complain when we’re part of the problem.

Our next stop is El Cap meadow, where climbers and tourists gather to gawk at the monstrous 3,000′ granite dome dominating the park. Sam, like Hannah and I, has seen all the documentaries, read all the books, and is conversant in the decades of climbing history that have unfolded here. The more one knows, the more one sees. I’m learning, slowly, and point out iconic features like the boot flake and great roof.

From the meadow it’s only a short walk to the base of El Cap. We crane our necks and give ourselves over to vertigo, looking upward at the frozen ocean of granite. Two haul bags sit at the base of the Nose, arguably the most famous rock climb in the world. We hear two climbers somewhere up on the first pitch, calling out to each other. I’m surprised they’re starting up this late in the evening. I catch the word “shitshow.”

We turn right and follow a steep ascending trail along the wall’s base. We’re beneath the Dawn Wall now, although I regrettably don’t know where the route actually starts. At one point, we scramble up onto a gentle slope of granite, where it seems that El Capitan has begun melting into the valley floor and then hardened again. We sit for a while enjoying the view, imagining what it would feel like to be up there, lost in the granite sea. I can at least say I’ve climbed “on” El Capitan, even if climbing it remains a distant dream.

—Our van is crowded enough with Hannah and me. With Sam, it’s simply hilarious.

We find a satisfactory parking spot on a dirt road just outside Yosemite National Park, but nobody wants to go outside because of the mosquitos. We play musical chairs while cooking dinner: chicken stir fry tonight, which requires two pots and a frying pan. It’s a lot for our little 1-burner stove and limited counter space.

We talk as we cook at and eat dinner, reliving the day’s adventures. Sam is as mesmerized by Yosemite Valley as I hoped he would be. It feels good to share this with him, as if Yosemite Valley was ever a possession of mine that I have to give.

June 25, 2024

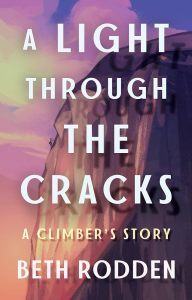

Reflections on Beth Rodden’s “A Light Through the Cracks”

One of my inspirations is rock climber Tommy Caldwell. I briefly recount his story, and its influence on me, in my book Eating Glass.

Caldwell’s story is one of growing through severe hardship, discovering new inner strength, and leveraging that strength to tackle a seemingly impossible challenge: free climbing the Dawn Wall of El Capitan in Yosemite Valley. Caldwell’s ordeal began in 2000 while climbing in Kyrgyzstan. Armed terrorists kidnapped him, two friends, and his sort-of-girlfriend, professional climber Beth Rodden. For six days they endured severe privation and forced marching. They didn’t know if they would live or die. At one point, the terrorists marched another prisoner out of sight and executed him. Their ordeal only ended when Caldwell shoved a captor off a cliff, enabling them to escape to a friendly military camp and back to U.S. protection.

The next year, Caldwell accidentally sawed off his left index finger with a table saw—an injury that would have ended the careers of most climbers. Caldwell came back with a vengeance, climbing harder than ever and knocking out one history-making climb after another. Then, in 2010, he divorced. In his memoir The Push, Caldwell writes candidly about Beth’s unhappiness, her emotional distancing, an affair, and an agonized back-and-forth season about whether the marriage could be saved. In the end, it couldn’t. Instead of succumbing to his anguish, Tommy directed his pain into a new project: climbing the Dawn Wall.

The documentary chronicling Caldwell’s life and ascent, The Dawn Wall, is one of my favorite movies. It came at a time when I needed it. I was dealing with challenges in my own life, and I found Caldwell’s relentless striving deeply appealing. I had given up climbing eighteen years earlier, after a near-miss that could have killed me. The film made me wonder how much I was letting fear rule me, both in climbing and life. What if I, like Tommy, possessed strength I could scarcely imagine? What might I be capable of?

In the past years since watching The Dawn Wall, climbing has become an important part of my life again, a source of community, and an arena for developing strength. I’ve faced and overcome fears and advanced further than I ever thought I could. I have Tommy to thank for that.

—Given the personal importance Tommy’s story holds for me, I immediately took note when Beth Rodden released her own memoir, A Light Through the Cracks. Rodden is a titan of climbing in her own right, with a long list of historical achievements, which alone would make the book worth reading. But she was also Tommy Caldwell’s wife and lived through many of the same hardships.

The best literature, in my view, does not take sides; it portrays three-dimensional characters, human, well-meaning, imperfect, finding their way through the world. That brings them into inevitable conflict and tragedy but also brings opportunities for goodness and redemption. That was the mindset with which I approached Rodden’s book. Much of the climbing world treated her harshly after the divorce, but I was eager to understand her story.

A Facebook post from Rodden set the tone for how I received this book. She posted several photographs, including an endearing scanned photo of herself and Tommy, barely more than teenagers. She acknowledges there was a time she never wanted to remember these moments again. But now, she wrote, she sees “two kids, doing their best, young and eager, learning how to adult together.” The compassionate tone hinted at a deeper story beneath the divorce, and the possibility of at least partial healing.

I needed to believe in that moment. Over the past two years, my own 19-year marriage had unexpectedly ended. There was so much I didn’t understand. Beth’s book and story, I hoped, would somehow speak to mine.

—The Light Through the Cracks is a very good book. Rodden is raw, brutal, and honest. It is surreal, re-living Tommy Caldwell’s well-told captivity story with her incredible gift for detail. Rodden’s version is visceral, nightmarish, and intensely physical. The horror of her captor squeezing up against them for warmth at night, and his public masturbation throughout their forced march; the lack of a discernible “thud” after their captors execute another prisoner behind a nearby boulder; the embarrassment of menstruating during their rescue, the congealed mess when finally peeling off her filthy clothes.

It didn’t take me long to realize that this is not a book about climbing at all, not at the heart. It’s a book about Rodden’s deep trauma, her reckoning with her deepest wounds, and her journey to healing and the reinvention of her life.

Rodden brings the same unflinching honesty to every dimension of her life. She does not shy away from the dark places but turns them over carefully, exposing them to the light. She writes about her struggles to feel attracted to Tommy, their lack of sexual chemistry, and her sense of being overshadowed by him (and by men in general) in the climbing world. Even so, she is unfailingly courteous to Tommy; one senses he has done nothing wrong, apart from being cheerfully unable to comprehend the depth of her struggle. She writes honestly about her affair, her guilt, and her feeling of being trapped between the “good girl” impulses that have always served her so well and her desperate yearning for a new kind of life.

The theme of embodiment emerges from every page of the book. Few us are comfortable in our bodies, especially women. Female athletes have long faced pressure to appear sexy. Climbers face additional challenges, and have a long and unfortunate history with eating disorders. The arch-nemesis of climbers is gravity, and a desire for incremental performance gains can drive toxic weight-loss behaviors. Rodden explores all of this: the way she carries her traumas, her ruthless disciplining of her body, its subsequent breakdowns, the way her sense of self-worth becomes entangled with body image and performance.

By the end of the book, Rodden escapes this destructive spiral. Pregnancy and childbirth, more than anything else, give her a new appreciation for the goodness of her body and help her to reimagine her relationship with both her body and climbing. A short, free Reel Rock documentary, This is Beth Rodden, provides a wonderful overture of the book’s themes on this point. She also finds constructive challenge and healing in her new relationship.

I’m glad Rodden waited as long as she did to write this book, because it gave her time to complete a dramatic life transformation. This is a woman who has grown through her midlife journey into someone tougher, wiser, and just as fearless. She has learned to relax her definition of achievement, pursue healing from her traumas, value friendships in a new way, and enjoy the simple pleasures of ordinary life outside of climbing.

The book also satisfied my hope for at least some insight into her post-divorce relationship with Tommy and his wife Becca. One senses they have put hard work into maintaining a positive relationship. Beth’s description of her friendship with Becca is particularly heart-warming. None of this could have been easy for anyone—I’m sure it still isn’t—but I found these passages hopeful as I navigate my own post-divorce life.

—Writing such a raw memoir is not easy, and releasing it into the wild is even harder. I know, because I wrote a raw memoir of my own. Eating Glass is about navigating feelings of personal failure, and along the way it becomes a much larger meditation on living a meaningful life. To this day, I fret over its rawness, the risk of oversharing, the critical ways it might be received. Occasional e-mails from readers assure me that the book speaks powerfully to those who need it.

Tommy Caldwell expressed uncertainty about writing his own memoir, The Push, in a 2023 podcast with Finding Mastery (31:00). He acknowledged that writing the memoir helped him understand himself and his experiences better, but he “was uncertain whether he was any better off for it.” It made him “darker” and “a little bit more angstful.” He was glad he wrote the book but also wondered if there is a “little bit of wisdom in blind optimism.” A listener senses that he will always look back on the book with mixed feelings.

I suspect Beth Rodden has similar anxieties about her book, so I just want to say loud and clear: its unflinching honesty is the source of its power. The highest praise I can give is that I told my 14 year-old daughter, a fiercely driven athlete, that I want her to read it.

I have to wonder what Tommy thinks about this. It’s one thing for Beth to lay it all out there; it’s another thing for him to see private details of his life in print. I’ll circle back to what I said about good literature, about the complexities of well-meaning people doing their best in life. If anything, the book heightened my respect for him. It’s possible to hold the humanity of both individuals, appreciate their honest humanity, and recognize that they walked very different life journeys in processing their captivity in Kyrgyzstan and everything thereafter.

As I conclude, it strikes me that I’ve written very little about Rodden’s rich descriptions of her formidable climbing career. Maybe that’s because the book fulfilled its purpose. Rodden’s career is impressive, but she puts it in the much larger context of a life.

Day 7: Routines and Departures

After our rest day —the day of plumbing and then a quiet riverside afternoon—we are ready to get back into action.

For an adventure trip on the open road, it’s amusing how quickly we have adopted routines. We love our coffee shop mornings and our afternoons climbing at School Rock. Today we see no need to deviate from that routine.

Travel always reminds me of the value of routines. The word routine has a negative edge, connoting dreary repetition or boredom. But at their best, routines are essential to helping us live the lives we want. The word derives from “a way, a road, space for passage” and suggests a “customary path for animals”, perhaps to drink water. Good routines are efficient, repeatable processes for reliably doing the tasks we consider important. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve appreciated the ability to create home routines that sustain my passions. On a good day, I wake up around five, brew a cup of coffee, and write until it’s time to wake up my children or prepare for work. That routine helps me complete one of my most meaningful and important tasks before most of the world rises. My afternoon and evening routines include exercise, time with my kids, and time with Hannah. I’ve repeatedly read that the lives of highly successful people often look quite boring, because their entire lives are structured around routines that support their calling. Stephen Wolfram comes to mind, who has taken this to an extreme; it looks over-the-top, and yet one senses he has designed exactly the life he wants.

A trip like this upends routines. We wake up in different places each day, and at different times. Our sleep quality varies with our campsite and itinerary. It’s after seven by the time we make it to the coffee shop, and my journaling has taken me out of the flow of writing my book. We eat intermittently throughout the day at odd times. Every day holds a different schedule. The rewards of this lifestyle include novel experiences, adventure, and delight at the unexpected. Yet our vagabond existence also comes with tradeoffs: tremendous time given to daily chores, a growing sense of fatigue, a severe decline in productivity. I partly came here to write, but I’m writing less than I did at home.

So we naturally develop new routines, structuring our vanlife days to swiftly deal with chores and maximize the things we care about: reading, writing, talking, climbing, resting in nature.

—Those routines are about to be disrupted, however: today is our last day in Donner Pass. This evening we will drive to Fresno, where we will stay the night at a Love’s truck stop to facilitate picking up my friend Sam from the airport in the morning. Then it’s off to Yosemite Valley.

Before leaving, we make one last trip to School Rock. On our previous two trips, we climbed Kindergarten Slab. Today we take on a new two-pitch climb, Kindergarten Crack, which begins by following a crack up a dihedral. Unlike the previous climb, this pitch is vertical. It isn’t hard climbing, but climbing anything vertical on trad gear is still a mind game for me. But it’s important to do something new, to keep pushing my limits outward, to ensure that our routines don’t lead to complacency. Within the daily framework we have established here, I want to keep growing.

The climb is uneventful. I feel good; I’m learning. What spooked me a few days ago now feels at least somewhat routine. Halfway up the climb, we belay next to another pair of climbers. I love chatting with strangers at our little improvised outpost 75 feet up a rock face, as if it’s the most natural thing in the world. Hannah and I both dream about trying “big wall” climbing someday and spending a night in a porta-ledge, a kind of hanging tent for multi-day climbs. This brief belay stop is enough for today.

—After our climb, we start our long descent down Highway 80 toward Sacramento and then Fresno. The pristine alpine environment transforms with each passing mile. The temperature rises. The pure blue sky becomes hazy with dust. This isn’t the California of postcards; it’s the inhospitable white space on the map between San Francisco Bay and the Sierras.

Still, it’s California. I introduce Hannah to In’N’Out Burger. Afterwards, we stop by Winston Smith Books in Auburn, a lovely independent bookstore. Continuing on my nature kick, I pick up a first edition hardcover of Arctic Dreams by Barry Lopez. Hannah finds a copy of Jack Kerouac’s The Dharma Bums, inspired by a discussion of the book in Kim Stanley Robinson’s High Sierra: A Love Story. Kerouac wrote the book after spending time in the Sierra Nevada and Cascades with the outdoorsman and poet Gary Snyder.

As we leave the mountains behind, we talk about the accessibility of wilderness. We’re both enchanted with Truckee, but the population enjoying this area is almost all white and affluent, with high representation from Silicon Valley. I spot three Tesla cybertrucks, a vehicle I’ve never seen in person before, amidst the Jeeps and luxury SUVs and other Teslas. I wonder about the barriers preventing other demographics from enjoying such a beautiful place. Basic supply and demand play a huge role. Wilderness as beautiful as Donner Pass is scarce, and what’s scarce inevitably becomes expensive. The median property value in Truckee was $675,000 in 2020, then nearly doubled after the pandemic. I can’t get upset at the demand, because I’m a part of it; I’m a reasonably affluent tech-minded professional who dreams of living in a place like Truckee. Perhaps the problem is on the supply side. Perhaps we have a crisis of wilderness scarcity, just as we do of housing scarcity.

The economics of California’s wild places are very different from Alabama, which lacks the concentrated grandeur of California’s mountains but has abundant forest, hundreds of small lakes, and a much smaller population vying for a place outside. I have learned to love this about Alabama: the multitude of campsites, the ease of making last-minute travel plans, the accessibility of the outdoors to all demographics. If the state’s wilderness lacks majesty, it at least offers everyone a place.

We pull into Love’s Truck Stop just after sunset. It has been a long time since I’ve seen such a big sky. It has its own kind of beauty, with the bold lights of the travel stop glowing hazily through the dust of the flat, empty landscape beyond. We’re at the opposite end of the socioeconomic hierarchy now. In the parking spot beside us, a leather-faced man sleeps in the driver’s seat of a battered blue pick-up truck. What I assume are his worldly possessions are wrapped in trash bags in the truck bed, presumably to protect them from rain. An emaciated trucker with a cigarette dangling from her mouth sets her pet possum loose in the dog park; when it escapes into the parking lot, perhaps drawn onward by some primal instinct to fulfill its destiny as roadkill, she leaps the fence and drags it by the tail back to the dog park, where she stuffs it into a zippered handbag.

There is something beautiful about all this too, this crossroads where the lives of so many human beings briefly intersect. This is my first time overnighting at a travel stop. It has its own subculture, and I take the time to slow down, look, and try to appreciate everything happening around me: the 24/7 bustle, the hundreds of families pouring through on their roadtrips, the rows and rows of semi trucks that serve as the arteries and veins of modern civilization. It’s a modern-day caravanserai, an American silk road.

June 24, 2024

Day 6: The Earned Life, or, There Will Always Be Plumbing

I have been in remote areas without Internet or cell service for the past two days. Rather than try to catch up, I’ll continue to post a day at a time, lagging my actual travels.

My trip entails a delicate balance of being and doing, and we’ve been doing quite a lot over the last three days. We decide to take a rest day.

We spend the morning in the usual coffee shop. We enjoy this morning ritual. Hannah likes slow starts, and this is my time to write. I’m supposed to be relaxing, but I’m churning out words at a crazy rate. I’m normally a ruthless editor of my own work. I whittle successive drafts down to sparse, pure essence of my original idea. My final drafts are usually half the length of the first. Now I’m barely editing at all—an experiment in letting go. Hannah tells me she prefers this style. It’s freer, looser, more approachable.

Afterwards, we seek out a deli where I have faint memories of eating the best sandwich of my life. I find a familiar photo on Yelp: the Full Belly Deli. We drive there and order sandwiches (the sandwich is the Dirka Dirka on jalapeno cheddar bread, and yes, it’s still good). Our plan is to find a quiet lakeside, eat our lunch, and spend the afternoon reading and talking.

As we head out to the van, I freeze. Something is wrong. Liquid is dripping out the bottom.

—Plumbing problems are one of my triggers. The original wound came one night in Jordan, when on a whim I decided to fix a dripping cap in my radiating heater. I rotated it a quarter turn, righty-tighty. The slow drip turned into a rapid drip. Oh no! Was it threaded backwards? Was this a Jordanian thing? I turned the valve a quarter turn back to the left. The drip turned into a steady stream. Then the whole thing came apart in my hands, and water gushed across the marble floor of my fifth-floor apartment. It was late at night, in a foreign country. I had no idea how to find a plumber.

My wife and I raced to find every pot in the apartment. We rotated pots under the gushing water, while I made frantic phone calls in babbling, broken Arabic to our building manager.

A plumber eventually arrived. He worked quickly and deftly. In minutes, he’d fixed everything. He stood up and wiped his hands on his pants.

“I spent several years working with the Americans in Iraq,” he seethed. “You Americans think you can fix everything.”

—According to the Enneagram, my greatest fear is being “being useless, helpless, or incapable.” Nothing does this more than plumbing.

On another occasion, I cracked a toilet tank while making an easy ten-minute replacement of toilet hardware. We had to replace the entire toilet.

Recently, compounding problems under my kitchen sink threw me into an abyss of rumination. I knew I should be able to fix this myself, but all I could think of was that day in Jordan, turning the cap the correct direction and watching a slow drip explode into a midnight crisis. It upended the orderly rules of the world, reversed logic. I was in a maze-like world where cause no longer matched effect. If I couldn’t trust myself tighten a cap, how could I fix anything?

I called a plumber. He charged $250 to tell me that he could fix it next week for $1200. Even I have my limits. I threw the plumber out (nicely) and started watching YouTube. A week-long saga ensued, with multiple Home Depot runs to buy armfuls of fittings I didn’t quite understand, and later putty, trying to make mismatched parts fit without dripping. Turning my curbside water off and on—what I thought was a sensible precaution—caused hammering that blew an underground valve and turned my front yard into a marsh.

And now this: my van, my escape pod, my portal into mountain life.

Plumbing has followed me here.

—A frenzy of troubleshooting ensues. I call my dad. I’m 44 years old, but dad still knows everything. I send him photos and videos. A cap is leaking under the the vehicle, below the shower. Back in the van, I find half an inch of water pooled in the bathroom. That’s frightening, indicative of a more serious problem. Where is the water coming from? We run some experiments and conclude the toilet is leaking, although we’re not sure if it’s the fresh water supply or the outflow.

My calm, cool persona cracks. I fall into the pit of self-loathing. I didn’t come out here for plumbing. I hate vans. I hate travel. I want to be in a tent—a fantasy of escape, nested like a stacking doll within the escape fantasy I’m already living.

My dad thinks I can fix this. I’d rather pay someone than spend an afternoon dealing with this, but the nearest RV servicer I can find is 30 miles away. This is supposed to be our day.

“Let’s take a break,” Hannah says.

—We make a stressful drive north on Highway 89, deep into Tahoe National Forest, away from RV service shops and from cell reception. We spend twenty minutes trying to find a quiet lakeside spot along Prosser Reservoir, but can’t public access. We return to the highway and keep driving, but no spot looks appealing. My phone indicates that we’ll cross the Little Truckee River in seven miles. I’m not comfortable driving that far into the forest with a malfunctioning van, but we do it anyway. My last bar of cell phone service vanishes.

We finally cross the river, and the spot is indeed heavenly: a convenient gravel turnoff, with secluded copses of trees along the banks of a shallow, babbling river. We set up camp chairs in the shade and eat our sandwiches. I listen to the silence. Gradually, the dark emotions drain away.

We run a few more experiments. The leak seems minor, it isn’t continuous, and it only manifests when the van is parked at certain angles. We can probably live with it. We’ll stay here for the night, broken plumbing and all.

—A delightful afternoon ensues. Time slows down. I plow through another pages of Macfarlane. Hannah alternates between Love & Will and climber Beth Rodden’s new memoir, about which I will write soon. We have leisurely conversations. The goodness of the day washes over me.

A phrase keeps surfacing in my mind: the earned life. It’s the title of a book by Marshall Goldsmith.

The earned life. I want life to be easy. I’m continually searching for ways to simplify, to eliminate complexities, to carve out time and space to live in a state of permanent fulfillment. It will never be that easy. Life never ceases presenting challenges, twists, and turns. There will always be plumbing.

A well-lived life has to be continually earned, over and over again, moment by moment.

As the sun goes down and Hannah and I button up the van for the night, I feel content. We have earned this afternoon together.

June 21, 2024

Day 5: Sketched Out

My wilderness journey thus far has been a tale of escalating adventure: arrival, settling in, hiking, rock climbing. The words have come easy. Today is different. It is a day of labored progress, creeping self-doubt, and persistence.

Our itinerary repeats the day before. We wake up beside the same concealed meadow, break camp, and head into town for several hours of writing at the Dark Horse Coffee Roastery. Then we head back to Donner Summit to repeat yesterday’s climb. By doing the same climb twice, we can focus on skill-building and efficiency. We aim for smoother climbing, faster belay transitions, and completing the climb in two pitches instead of four. If we’re fast enough, we’ll have time to knock out a second route.

I feel good, driving up to the summit. Yesterday’s anxiety has melted away; having done the climb once, I feel good about repeating it. As we gear up at our van, we are already incorporating lessons learned: leaving excess gear behind, bringing walkie talkies in case the wind is howling, using a better technique to coil and carry our rope.

It is another gorgeous day. I still can’t believe I’m here, in this gap between lives old and new. Hannah and I still feel exhilaration from yesterday’s successful climb. It’s a good day to get on the rock again, for continual improvement, for pursuing mastery, even if it’s just on a baby route.

—My biggest challenge when I lead trad is running out of gear. As I climb, I place protective devices like cams or nuts in cracks, then clip the rope though them with slings and carabiners. If I fall five feet above a piece, I’ll theoretically only fall about ten feet—five to the piece, and then five past it before the rope goes taut. If the top piece pops, it means a terrifying fall to the next piece down. This incentivizes a new trad leader to “sew up” routes by placing gear often. If I place cams every two feet, falls will always be small. The pieces also back each other up.

Unfortunately, gear is finite. I carry two full sets of cams plus an assortment of nuts, which is a lot. Still, I run low on gear on every trad route I climb. A climber needs to end each pitch with at least three good pieces, to build a triple-redundant anchor for belaying the other climber up to join them. Those pieces need to be the right sizes to fit the cracks at the intended belay spot. This is one reason I’m so anxious about the unknown; I don’t know what size of cracks await. It would be highly inconvenient to arrive at the belay without the necessary gear.

This is why Hannah and I needed four pitches yesterday to complete a two-pitch route. We wanted to stay within sight and earshot of each other, but I also wanted to create belay anchors while I still had adequate gear clipped to my harness.

To improve as a trad climber, I need to place protection less often. This means longer runouts and the potential for longer falls. Doing this safely requires developing an exquisite ability to evaluate risk. This route is less than vertical, which means there are long stretches where a fall is highly unlikely or would just mean a short tumble. The safe and efficient thing to do, counterintuitively, is to cruise through without placing protection.

—The first pitch starts strong. I move efficiently, placing gear where needed, forcing myself to avoid placements when unneeded. I feel healthy and strong. Movement over rock always feels good, a comprehensive exercise of body and mind, like yoga. I pass the ledge where we belayed yesterday. Good. I’m doing better.

Something changes after that: brain fog, unease, difficulty. I struggle to find the right way to protect my next move. I remove one cam after another from my belt loops, hunt for a good placement, and then trade it for another size. My headspace is suddenly different from yesterday: I feel less confident, more fearful. I eventually find a good placement, but my nerves remain abuzz.

It’s hard to pin down why I feel “sketched out” at some times and not others. Yesterday was the scarier climb: my first multi-pitch trad lead, my first time on this route and in this location. I felt sick with anxiety beforehand, but once I started, I felt great the whole way. Today everything is familiar, so why the nerves? I suspect it’s because I’m pushing myself harder, expecting more of myself. This is yet another case where climbing mirrors life.

—Later, sitting down to write, I feel the same sense of being “off”—a headspace not quite right, a simmering anxiety. The writing has flowed naturally thus far. Despite my nerves, I’ve felt good about sharing these posts. I’m ignoring the howling demons, writing what I want, with no expectation of an audience.

Not today. Something has changed. The thought of writing feels wearisome. I’m feeling something I hoped to avoid on this trip: pressure. The writing takes time, but at least it’s time I enjoy. Sharing online entails less enjoyable tasks: copying into WordPress, reformatting, adding hyperlinks, sifting through photos, posting, sending an email version to my mailing list, sharing links on Facebook and Instagram. Every time I share, I’m reminded why I hate social media. And yet the only way I’ll ever break through my current barriers as a writer is to share, to dispatch messages in bottles. Social media is the devil’s bargain every creative has to reckon with. It’s a bit like placing gear, I suppose, doing it just enough to stay alive but not so much that I find myself bogging down.

The sense of pressure springs directly from the strength of my commitment to writing. Just like this climb, I suppose. I’m sketched not because of inexperience, but because I’m consciously trying to become better.

—Climbing while sketched is a necessary part of the sport. Just like writing while sketched, or running a business, or committing to a relationship.

At day’s end, after we return to our van and enjoy a dinner of ravioli and meat sauce with a bottle of Cabernet, we watch the wonderful documentary Fourteen Peaks, about Nepali climber Nirmal Purja’s record-shattering effort to climb all 14 peaks taller than 8000 meters in just seven months. Nirmal is a larger-than-life character, charismatic, bold, passionate. He repeatedly emphasizes the need for courageous leadership in precisely those moments when our nerves are fraying.

I don’t dare compare myself to a veteran mountaineer like Nirmal Purja. But I can at least take his lessons, apply them in my own small way.

— I set up my first belay station thirty feet higher than yesterday, which is something, at least. I could probably go higher, but there isn’t much gear left on my harness. I build an anchor and prepare to belay Hannah up. We miscommunicate, and she nearly starts climbing before she’s on belay—a dangerous goof. We both catch her mistake immediately, but it’s enough to rattle her nerves.

I set up my first belay station thirty feet higher than yesterday, which is something, at least. I could probably go higher, but there isn’t much gear left on my harness. I build an anchor and prepare to belay Hannah up. We miscommunicate, and she nearly starts climbing before she’s on belay—a dangerous goof. We both catch her mistake immediately, but it’s enough to rattle her nerves.

She climbs on. We’re orderly and efficient at the belay station, but neither of us feels the joy we did yesterday. We’re too focused on process and technicalities to savor the views. Again, the price of improving.

The second pitch goes much better. My nerves settle down. I’m feeling confident again. My placements feel solid and safe. I use less gear than yesterday. I very nearly make it to the top, but once again, I run low on gear. I sigh and build an anchor, which means we’ll need to make a third pitch. Not ideal, but better than yesterday.

When Hannah arrives at the belay station, we’re both in good spirits again. We take our time there, enjoying the views. This whole trip is, in our shared vocabulary, a dance between being and becoming—of enjoying the present moment without expectations, and striving to grow. Today’s climb embodies that tension.

June 20, 2024

Day 4: Expanding Boundaries

Location: School Rock, Donner Summit

I feel sick with dread as we chug up the winding mountain road west of Truckee. I am about to do something hard, something I’ve never done before, something that fills me with fear.

The fear feels incongruous with everything else in my life. It is a gorgeous day, the best kind of California day, with brilliant sunshine and fresh mountain air and temps hovering in the 70s. There isn’t a cloud in the sky. Before our trip I was worried about California’s notorious wildfires and the consequent smoke, but I can see to the horizon in every direction: Donner Lake gleaming blue far beneath us, great cracked walls of granite rising out of the evergreen trees all around.

It feels good to be in an adventurer’s paradise. During our morning in the Dark Horse coffee shop, where I did my day’s writing, we watched them file through one after another: puffy down jackets, hiking boots, unkempt hair. They drank their coffee and scrutinized guidebooks before embarking on their adventures of choice.

On our long, winding drive towards the summit we pass hard-working cyclists. We wave. Climbers work their way up cracks. Everyone is happy, wind-blown, bathed in sunlight and mountain air. The vehicle turnarounds are full of Jeeps, trucks, and vans with off-road tires, adorned with solar cells and jerry cans. It’s Mad Max in photographic negative, a mechanized utopia.

But my sense of foreboding grows as we approach the summit. I’m about to lead my first multi-pitch trad climb, a major milestone in my climbing journey.

The only way to get better at hard things is to do hard things. It’s a truth I hate to admit. If we want to expand our limits, we have to continually step over the line of everything we’ve done before. I think of Sam Gamgee’s famous words to Frodo in The Fellowship of the Ring: “If I take one more step, it will be the farthest away from home I’ve ever been.” Expanding our limits always means a step into the unknown, where anything might happen.

—

This day has been a long time coming. I’ve had the raw climbing ability to do multi-pitches for years. In theory, I also have the skills. Two years ago I took a multi-pitch climbing class in North Carolina, which taught me everything I needed to get started. A year later, I hired a guide to take me up two routes on Looking Glass Rock. The next step was to “tie into the sharp end”, as climbers say, and lead a climb of my own.

The problem is that I live in central Alabama. The nearest climbing gym is 90 minutes away, the nearest crag twice that. The hills of northern Alabama hold some wonderful climbing, but the walls are all single-pitch, meaning no taller than a single rope length. To find multi-pitch climbs, I must travel even further, to North Carolina. The climbing there is different and unfamiliar; my skills aren’t quite matched. I live too far away to practice. The end result is a plateau of my climbing skills as flat and featureless as Alabama itself.

One of my goals for this trip is to break through that barrier. We chose Donner Pass as our first destination for a specific reason: the aptly-named School Rock. I couldn’t ask for a better first multi-pitch. The impressive-looking slab contains a row of relatively easy two-pitch routes. It’s only two minutes from the highway, and after each climb, climbers can simply walk off the back and down a gully. Even better, perched as it is near Donner Summit, the views are extraordinary. For a beginner route, it feels like an epic mountain adventure.

My fear seems silly. This is as easy as it gets. The bold, frightening route I’ve picked out for myself is called Kindergarten Slab. My guidebook rates it as 5.3; if that’s right, then it’s theoretically the easiest vertical route I’ve ever climbed. Further to the right is Kindergarten Crack, and a little ways after that is Junior High. Meaning: I’m at the bottom of the bottom of the multi-pitch learning curve. At least we’re skipping Nursery School Slab, which is full of kids on top rope.

Despite the low grade, climbing is climbing, and a mistake can kill you. Fears circle like bats. Climbers talk about differentiating between rational fears and irrational fears, but it’s often hard to know in the beginning which are which. I fret over all the things that can go wrong. This is a “trad” route, which means there are no bolts in the rock to clip the rope into as I climb. Instead, I’ll be placing cams and nuts in cracks. Falling on a bad placement could pop a piece, extending a fall. If I use up my pieces too early, I’ll find it hard to protect the upper reaches of a pitch. I also have Hannah to think about, a much less experienced climber. My life is in her hands, and hers in mine.

If something goes wrong partway up, getting down again won’t be trivial; there are no rappel stations to facilitate a rapid descent. Once I leave the ground, the safest and easiest way to get off the rock is to reach the top.

—All of this raises the question: why climb? Meditating on this question is part of my ritual encounter with fear. First comes the anxiety, then the reflection, then the thought that perhaps it’s time that I quit. Maybe climbing has already given me everything I need. But each time this happens I eventually overcome my fears and start the climb, and rediscover the sport’s rewards all over again.

Many of us are familiar with the concept of flow, of being so immersed in something that we lose our sense of time and our awareness of the world around us. Unfortunately, the concept has often been reduced to a productivity hack, a tool for getting more done. It is indeed critical for productivity, and I have largely tried to structure my working life around the achievement of flow states. But when I read Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s marvelous book Flow, which introduced the concept, I was surprised to discover that he wasn’t writing about productivity at all; he was writing about happiness.

“It is by being fully involved with every detail of our lives, whether good or bad, that we find happiness, not by trying to look for it directly,” Csikszentmihalyi writes. Flow is a state of immersion and participation in life itself. Challenge and expansion are essential to these moments of optimal experience. “The best moments in our lives are not the passive, receptive, relaxing times . . . The best moments usually occur if a person’s body or mind is stretched to its limits in a voluntary effort to accomplish something difficult and worthwhile.”

Climbing, at its best, is a pure expression of optimal experience—the crystallized essence of the conditions that create flow. And the continual process of encountering and transcending limits brings a feeling of vitality that carries over into other domains of my life.

There is a yin-yang quality to the two major aspects of this trip: climbing and writing. My fears as I drive up to School Rock mirror my fears about my writing. Writing daily reflections, and sharing them online, awakens the same primal sense of danger. I don’t know why. But doing hard things requires doing hard things. Writing requires writing. Climbing requires climbing.

—When we arrive at the turnoff near Donner Summit, other climbers are gearing up nearby. I verify we are in the right place. Then I pull out my guidebook. The guidebook’s pictures are good, and I immediately identify the wall. That alone is enough to dissipate some of my fear. Knowledge is power. It is the uncertainty I fear above all else.

We hike to the base. The climb feels intimidating but it also looks very doable. Alongside my anxiety rises a new feeling: confidence. This climb is asking me trust that confidence: my years of climbing, the skills I’ve acquired and that Hannah and I practiced relentlessly in the weeks prior to this trip. It’s the same thing that my three-week writing project is asking of me: to trust myself.

We gear up and double-check each other. Then I start the climb.

The climbing isn’t hard. I could do this whole route in ten minutes on top-rope. But leading is a different animal, especially trad leading. I feel compelled to protect every move where a slip would be consequential. I climb slowly, placing abundant gear.

Pushing our limits can be messy. Most of my forays into the unknown are highly embarrassing, at least at first. It’s a necessary stage in building competence. One model depicts four stages of competence: unconscious incompetence, conscious incompetence, conscious competence, and then unconscious competence. I’m somewhere between stage 2 and 3, sewing up the route with too much gear, knowing that developing competence will take practice and time.

I build a belay anchor earlier than planned, then belay Hannah up to me. When she arrives, we are both beaming. Something miraculous has happened during that first pitch: my fears have mostly dissipated. I feel vibrant and alive. I’m realizing that an imperfect performance is still good enough, that we can still climb safely, that I have the skills and flexibility to adapt. We feel intoxicated by the sunshine, the wind, the exposure. We’re really doing this!

I build a belay anchor earlier than planned, then belay Hannah up to me. When she arrives, we are both beaming. Something miraculous has happened during that first pitch: my fears have mostly dissipated. I feel vibrant and alive. I’m realizing that an imperfect performance is still good enough, that we can still climb safely, that I have the skills and flexibility to adapt. We feel intoxicated by the sunshine, the wind, the exposure. We’re really doing this!

Our hours practicing in the garage and at Sand Rock pay off at the belay station. We are slow but safe, meticulous, and orderly. When we’re ready, I start up the next pitch, and we do it all again.

—It feels exhilarating, topping out. Our performance was laughable. It took us almost four hours to complete the easiest climb on this face and it somehow took us four pitches to compete a two-pitch route—an extra safety precaution so we could always see and hear each other, given our novice skills. But we did it.

At the top I make a list of lessons learned, things we need to do better, skills we need to practice. It’s a lifelong habit, rooted in my training as an Air Force pilot: the flight isn’t over until the debrief is complete. It’s how we get better.

We hike down the gully back to our van, clean up, and sit in camp chairs overlooking Donner Lake below. We have taken one more step. Our world is larger.