Mark D. Jacobsen's Blog, page 3

June 19, 2024

Day 3: Why Do We Travel?

Location: Dispersed Camping on Highway 89, Donner Peak

Travel forces a reckoning with the question: what is it that we’re seeking?

If the great 20th century psychologists taught us one thing, it’s that unconscious impulses guide so much of our lives. We follow yearnings and impulses that we ourselves scarcely understand. A person can spend a lifetime sifting through the accreted geological layers of their own life, unearthing reasons and explanations, all of which are only hypotheses. We never find bedrock, just mystery and wonder the whole way down, into the substrate of which Annie Dillard so poetically writes.

I feel those impulses quite strongly, because I’ve committed so much time and effort to listening to them. I continually try to dial down the noise, to shut out distractions, to let that faint pulse be heard. It’s like searching for starlight in a sky irradiated with the light waste of industrial society. The faint glittering swath of the Milky Way does not yield itself to casual glances skyward; one must intentionally seek those rare spaces left in the world where ancient ways of seeing are still possible. One must shun every other light.

We live in a society that has invented and commercialized innumerable ways to protect us from the dangers and uncertainties of our own deepest stirrings. To listen, we must dismantle, create space. Antoine de Saint-Exupéry wrote, “Perfection is achieved, not when there is nothing more to add, but when there is nothing left to take away.” That is true of all crafts, not least writing, and it’s true of life. As we subtract the non-essential, we see and hear more. As our own inner callings become audible, they pose hard and vital questions about their origins, their meaning, and what they ask us of us.

It is those impulses that brought me here, away from my usual life, away from a cycle of striving and achievement. It was a near thing. Three weeks in the mountains was not my original plan. I’d applied for and been accepted into a Complex Systems Summer School at the Santa Fe Institute, the beating heart of complexity science, a kind of shining tower for my academic ambitions that I felt unable to achieve in traditional academia. It was a stepping stone towards a book I want to write, a magnum opus distilling two decades of studying war—another call from the soul. But something felt off in a way I couldn’t explain. Something deeper called. A time of letting go, of relaxing ambitions, of disappearing into a wilderness where anything or nothing might happen.

—Why do we yearn to travel? I ponder the question throughout my first full day in California.

It is everything I hoped. We awake in the forest, brew coffee, then drive down to the Boca Reservoir, where we set up camp chairs. I write for hours, at first freezing in my down jacket and then roasting when the sun breaks over the hills. Mountain life always entails a forceful surging between extremes. I alternate writing with reading, Hannah beside me. We periodically break the silence to share an author’s brilliant insight or gorgeous line of prose. Some conversations fall away; others take on a life of their own. We follow the thread back into eventual silence and a return to our books. We feel we’ve had a full, rewarding, and timeful day, and it’s not yet 1:00pm.

Enjoying a moment atop Donner Peak

In the afternoon, we drive up Donner Pass Road to the summit. Along the way we pass climbers, clinging to cracks in towering granite walls like brightly colored insects. It’s awesome and intimidating. We’ll be back here soon, making our own forays into the vertical. Today it’s a hike, beginning at the highway and progressing up steep winding switchbacks, across a short snowfield, and up through a stream of snowmelt to the summit of Donner Peak. The scenery is spectacular. It is, I hate to say, everything that Alabama is not.

The questions about why we travel surface as we descend back to Donner Lake and the town of Truckee. We need showers. This is no trivial matter. The van has small indoor and outdoor showers, suitable for quick sponge baths, but we’re conserving our finite water supply. The nearest truck stop is thirty miles away. We call gyms, asking if we can pay to shower. No. We pay $10 to enter a state park, disregarding signs notifying us that showers are for campground guests only. My brief foray into outlaw life ends when we enter the bathhouse and discover that the showers require tokens.

We give up and search for a campsite. A pullout in Tahoe National Forest leads us to a dirt road and on to a secluded meadow. The meadow is huge, invisible from the freeway, ours for the taking. It’s dreamlike, alive, the kind of meadow that would catch my breath in an open-world video game, speckled with bright flowers and aflutter with butterflies. We shower outside, unconcerned about being seen.

Anxiety creeps in as the sun sets. For all its beauty, the open meadow leaves me feeling exposed and vulnerable—some evolutionary instinct, I suppose, protecting me against predators that might be stalking me from the bushes. We have no cell service. Before bed we place a can of bear spray near our heads and ensure the van is ready to drive away.

I sleep well, despite my sense of vulnerability. Then, around 1:30am, we both awake to a loud thunk under the van. Five minutes later, it happens again. It is a heavy mechanical sound, like something striking the van’s exterior. Such an isolated sound can’t be a bear. A sneaking human? I jump when it happens again. Eventually, I take the dreaded step of yanking the sliding door open and stepping outside with a flashlight, fully expecting bear claws or human hands to reach out of the darkness. Hannah is in the driver’s seat, ready. I sweep the flashlight beam through the dark trees. It’s a scene from a horror movie, the suspenseful moment before all hell breaks loose. There is nothing. We’re alone.

Back inside, I systematically work through the van’s system. I’m a C-17 pilot again, running checklists, isolating systems. When I disconnect and reconnect the van’s batteries, the sound stops. A gremlin in the electrical system, then. We sleep.

—What is it that I’m seeking out here? What are any of us seeking?

It can’t just be simplicity. Van life, like the tiny house movement or its other minimalist cousins, makes promises of ultimate simplicity. Living small and mobile is not simple. Even the simplest task is hard. Backpacking, tent camping, or hotel stays aren’t any easier. Simplicity is a home, hot water, a kitchen, storage space.

I have a theory about this, after researching and daydreaming about simpler ways of living: the simplest way to live is the suburb. Humans are biologically programmed to conserve energy, and the suburb is the pinnacle of low-energy living. Cookie-cutter houses, straightforward appliances, small yards, easy access to schools and grocery stories and all the other essentials of living. Maybe it isn’t simplicity that I’m really after.

Travel offers beauty and wonder, to be sure. The Sierra Nevada mountains offer it in spades, and there’s no doubt that’s one of my major motivators. The mountains bring me to life in a way that nothing else does. That is Alabama’s one great deficiency for me. And yet beauty and wonder aren’t enough to sustain a whole life.

Adventure is another draw. I’m partly here to climb, to test myself, to expand my limits. That is another one of those elusive unconscious drives, which raises deep questions worth unpacking another time.

Many of us want to learn about places, people, and cultures different from our own. I share this desire, and yet I’ve never felt like my travels live up to my hopes in this regard. The way to know a culture is not to pass through, but to plant oneself in its cultural soil. Two years in Jordan gave me the opportunity to begin learning a culture. My other travels feel superficial, a mere window tour. I feel guilty, admiring mountain vistas when I don’t know the names of the trees, the geological processes that thrust these peaks up through the earth’s crust, the history of the peoples who lived here. As for getting to know a culture, the native populations of a town like Truckee are almost invisible; Hannah and I live among the countless other travelers, the vagabonds, the tribeless.

I wonder if what I’m seeking is simply novelty itself. Difference for its own sake. There is a long evolutionary story to tell here, anchored in the complexity science of which I’m so fond. Complex systems—human minds, civilizations, life itself—need novelty the way humans need oxygen. Novelty is the raw grist for evolution, the source of all new features and ideas and behaviors, the material we sift through and parse and separate and recombine to move ourselves and our world forward. Without novelty, there is only stagnation, a dreary sameness. Stagnant systems are dead systems. Chaos and complexity scientists have long known that life thrives at the edge of chaos, where an influx of novelty keeps systems fresh and adaptive. Thriving systems balance familiar, effective patterns with continual change.

—It’s an abstract way to think about camping in the mountains, but then, I’ve always been an abstract thinker. That’s my own personal way of developing familiarity with a subject that catches my interest: not merely observing the empirical details, but pondering the deeper structures, the mathematical scaffolding that lies beneath.

These abstract insights lead me right back to practical living. If novelty holds intrinsic importance, then it must do so for good and practical reasons. I can think of many. The novelty of travel allows me to experiment with being someone new. Novel experiences provide the raw material for my writing. Shared novel experiences allow Hannah I to grow our relationship, learn about each other, and build memories. Novelty seems to be important for revitalization. For me, rest does not entail passivity but rather active enjoyment of meaningful experiences.

But if complexity science teaches us the importance of novelty, it also teaches us the importance of stability. Systems thrive at that knife-edge. Many of us, myself included, daydream of travel as a permanent state of being. That’s a siren call, I think; a life of permanent novelty would prove exhausting and eventually unfulfilling. If we are wired for travel, we are also wired for homecoming.

In my reading of Landmarks this morning, I came across this lovely passage in which Macfarlane offers a tribute to his friend Roger Deakin, a writer who lived in the same home for forty years while also traveling extensively and indulging his love of wilderness:

“… his writing [showed] people how to live both eccentrically and responsibly, and by both dwelling well and travelling wisely, he resolved in some measure the tension between what Edward Thomas called the desire to ‘go on and on over the earth’ and the desire ‘to settle for ever in one place.'”

June 18, 2024

Day 2: Lifting Our Eyes Beyond Ourselves

Location: Boca Reservoir, Tahoe National Forest

This morning I am reflecting on the relationship between mankind and the natural world. Specifically, I am thinking about my own relationship to nature.

The first book I’ve selected for my three-week mountain trip is Robert Macfarlane’s Landmarks, a book about “the power of language to shape our sense of place.” Macfarlane compiles rich glossaries of words describing the subtle details of particular landscapes. These are dying vocabularies, on the verge of extinction because human beings have lost their connection to the land.

Language defines how we think; it filters what we can even see. A seemingly barren desert or moor springs to life when we can speak the names of all the variated lifeforms inhabiting it, the subtle hades of color, the contours and features of its geography. Human beings have largely lost their sense of enchantment with the world—the feeling of mystery, the awareness of incomprehensible forces shaping the world around them—but Macfarlane writes that the right language can restore intimacy with nature and re-ignite enchantment.

I read Macfarlane while sitting outside my van, in the biting cold before the sun breaks over the hills to the east, watching the mist rise off the Boca Reservoir west of Reno. Macfarlane’s writing always gives me much to think about, but this morning I’m thinking about his intense focus on the land itself. When he writes about nature, he writes about things outside himself. He almost recedes from view as an author, at least in this morning’s chapter. He is not so much a character in the book as the invisible cameraman filming the cinematic masterpiece.

It’s very different from how I write, and how I think about the world around me. Here I am, sitting in a gorgeous landscape I’ve dreamed about for months. I am watching sunlit ground slowly overtake shadow, while formations of birds soar silently past over the reservoir. I could spend hours walking the shoreline, enumerating the different species of life I find, even if I don’t know their names. But I struggle to turn my attention outward. The locus of my attention is so often inward, on my place in this landscape.

—Yesterday was the load-and-go day: a series of lessons from dad on operating the van’s systems, grocery runs to Costco and Walmart, transferring our belongings from suitcases to cramped storage lockers in the van. After that we made the seven-hour drive from Boise to Reno.

It was a good drive, easy and uneventful, full of rich conversation. Hannah is reading Rollo May’s Love & Will, which led to discussions about free will, determinism, and sources of hope for human beings who feel so little agency over their lives. May, writing in 1969, believed the invention of nuclear weapons broke something in mankind; humans lost all sense of control over their lives. I think May is wrong; I think humans have always felt this way.

At long last, just past Reno, we turned off I-80 in search of a campsite. On certain public lands campers can engage in “dispersed camping”, which is an elegant way of saying they can camp wherever they want. That is our plan for the next three weeks. We have no reservations, just a self-sufficient vehicle with all the life support systems of a small spaceship.

That doesn’t make it easy. I’m new at this. It’s simple in theory, but there’s a lot to learn.

Our arrival was exactly what I feared. I’d chosen Boca Reservoir based on a reddit thread about dispersed camping recommendations, but believe it or not, the Internet was wrong; the reservoir was serene and beautiful, but when we arrived we discovered that dispersed camping there was illegal. After a pause for dinner, we loaded up the van again and headed deeper into the forest, to a set of GPS coordinates I’d also unearthed on reddit.

This area looked more promising. Signs permitted dispersed camping. We saw tents through the trees. The paved road turned to dirt, but it was in good condition and we were clearly close. We continued up the road in search of a good spot. Things quickly got dicey, when the road narrowed and steepened. We found ourselves ascending a winding forested hill, with nowhere to turn off. The van had low clearance, and worse, had highly flammable Lithium batteries mounted behind the rear axle. The sun was getting low; it would be dark soon. I felt rising anxiety, wondering if we should reverse all the way down the hill before sunset or keep going in hope of a turnaround. My mind played vivid scenes of striking the batteries on a rock and burning my parents’ new van to cinders.

In the end, we found a place to turn around and pulled into a patch of dirt in an otherwise unremarkable expanse of trees. By this point, I was mentally and emotionally drained. I don’t like feeling incompetent. Hannah consoled me. We’re fine, she said. We’re here.

We buttoned up the van, shutting out the darkening forest, and went to sleep.

—Our first night of van life is a parable, I suppose, for the complex ways we interact with nature. I yearn for close contact with pure nature but it’s always mediated by human needs and the technologies of survival. Even our purest excursions into nature, such as backpacking, now rely on extraordinary technology: down jacket, boots, Gore-tex, water purifiers. We spend inordinate amounts of time meeting basic needs for water, food, and shelter. Even as we enjoy a landscape, we’re thinking about the logistics of moving safely through that space. On this trip I’m also thinking about state and local camping regulations, axle clearance, and Internet availability for GPS guidance.

Even in the heart of nature, it’s easy to lose sight of nature. We have ourselves to think about.

That becomes especially apparent when I write. When I write, there’s no hiding. Writing makes my thoughts transparent. I’m partly on this trip to find my voice, and I’m little appalled at where my voice wants to go: inward, to myself, to what my encounters with these places unearth in me. It is hard to let the places themselves be enough. I have a new reverence for the masters like Macfarlane, who can so effortlessly disappear in their writing.

Maybe that is one reason why it’s so healthy to enter the wilderness. The wilderness poses a continual challenge: to lift our eyes, to look beyond ourselves, to see a world more rich and immense than we can imagine. It is sometimes good to feel small, to sense our own unimportance in the bigger scheme of things.

June 17, 2024

Day 1: Escape and Commitment

Location: Birmingham-Shuttlesworth International Airport; Meridian, Idaho

Something is filling them, something

That is like the twilight sound

Of the crickets, immense,

Filling the woods at the foot of the slope

Behind their mortgaged houses.

Those are the concluding lines of Donald Justice’s brilliant poem Men at Forty. It is a hopeful and dignified characterization of the threshold at which we stand. Something good and noble is rising in us that will allow us to give back to the world: experience, confidence, a truer sense of self, a willingness to set aside the unimportant to focus on the vital and vitalizing. It’s true that we feel our limitations and the rush of time—”Men at forty // learn to close softly // The doors to rooms they will not be // Coming back to”—but this only creates the space for an expansiveness of soul.

That poem has resonated for years. My military retirement feels less like a career move than molting or metamorphosis: wriggling out of one skin into a new, larger life. Erik Erikson’s 1950 model of psychosocial development posited that human beings grow through eight stages. Each stage entails a developmental task, which the individual must complete or else face “stagnation and emotional despair.” In late middle adulthood, Erikson posited, we shift from “career consolidation” to “generativity”, one of my favorite words, which has earned its way onto my personal list of core values. For Erikson, it meant “Concern for establishing and guiding the next generation.” The word also denotes creativity, building, “the quality of being able to produce or create something new.”

So: midlife, renewal, a swelling sense of purpose, a recommitment to my writing, three weeks in the mountains to forge a new identity.

But about those mortgaged houses…

—Rewind one year, in the thick of the bad times. My wife and I are separated and waiting for the divorce papers to clear the court. Then she gets cancer (she is better now). I’m drowning financially, paying two mortgages and for a slew of home repairs after our long-term renters suddenly bail from our rental house (I eventually get repaid when we sell).

Everything seems to climax at once, right as we’re entering the infernal summer, a time when even native Alabamans say you should escape the state with your life. It’s miserable, sweltering, mosquito-ridden. Right at this moment, my home air conditioning goes out. The unit is old and failing, the HVAC technician tells me. He can re-fill it with coolant for a lot of money, but it will probably leak again, or he can replace the unit for an ungodly amount of money. I can’t afford the replacement so I pay for the band-aid fix. We limp along through that summer.

Fast forward to a week ago. The kids are out of school. I’m done teaching. Life is amazing. Hannah and I take the kids camping before they leave for Africa, then prepare for our three-week getaway in the California mountains. We’re only a few days out from the trip when Montgomery’s temperatures skyrocket and I have a dreadful realization: it’s getting really, really hot in my house. It feels exactly like last year. Our house sitter comes over to feel things out. He’ll be fine, he says. Given our upcoming trip, we decide to wait to replace the air conditioner until we return.

Now it’s the night before our trip. We’ve just dropped the kids at the airport. We return home late and pack our last things for a 0430 morning departure. We go upstairs to catch a few hours sleep, only to find that it’s 83 degrees. On that very night, the night before my celebratory escape into the mountains, my home HVAC system has completely died. A heat wave is forecast to begin the next day, with temps rising to the high 90s. We have four pets.

I’ve been through too much these last few years to feel rage. Instead we lie there hopelessly, unable to sleep, sweating in the heat, feeling a kind of despair at the universe’s cruel jokes.

Hence Donald Justice’s last line, with his 40-year old father gazing out at the woods and his great new destiny. He can only see it because he has momentarily turned his back on the house, the mortgage, the entangling commitments.

—I’m hardly the first person to daydream of escape into a commitment-free lifestyle in the mountains. The #vanlife movement exploded in popularity during the pandemic. The symbol of retreat today is not a $300,000 RV or a second home in Tahoe, but rather a Mercedes-Benz Sprinter Van, tricked out with a bed and kitchen. These vans are Instagram ready, enabling intrepid adventurers to celebrate #vanlife amidst spectacular vistas from exotic locales.

Nellie Bowles wrote in the New York Times, “Vanlife has been an influencer trend on Instagram for years. It usually involved a good-looking young couple in a van posting gauzy portraits of each other and sweeping scenes of the places they visited. The fantasy life they sold is freedom and simplicity, a radical reduction in burden — but not comfort. For these are not backpackers looking tired and worn, with massive calves and wild hair. Vanlife is an aesthetic trend, closer to the tiny-home movement, yet even richer, lusher and typically sexier.”

I find this movement fascinating. One day I search for the #vanlife hashtag on instagram. Bowles nailed it. Three of the top nine photos are of attractive young people posing in lush, exotic locations. In the first, a ripped, shirtless man and bikini-clad woman stand waist-deep in some jungle pool, kissing. In the second, a topless woman in cutoff jean shorts, shot from behind, surveys a field of vivid green grass. In the third, a nude woman stands calf-deep in crystal water, arms outstretched in a sun salutation. Above her bare ass, naked back, and outstretched arms, her van is parked on the shore. I couldn’t create a better parody of this hashtag if I tried.

The bullshit factor is so high, but I won’t lie; it doesn’t stop me from feeling the appeal. I yearn for escape. I want an escape pod that can sweep me and my family off on incredible adventures in the outdoors. I couldn’t afford a van, but I did buy a tiny converted cargo trailer that holds our camping gear and sleeps three. We’ve used it dozens of times. It’s exactly what we wanted it to be: a mobile base camp for family adventures, crammed into every open space of our calendar between work days, guitar lessons, and basketball practices. My life involves a continual shuttling between civilization and wilderness.

—And this is where I part ways with the Instagram-style #vanlife crowd. I’m not interested in selling a myth of eternal escape, even though that sounds superficially appealing. I do get it. I yearn to shed commitments. I’m tired of paying bills. I’m bored to tears with much of what passes for work. I’d love to erase events from my calendar for once, instead of continually adding them. It’s an appealing fantasy, hitting the road with a few loved ones in pursuit of wonder, joy, and adventure, with none of the work entailed.

But none of us live such commitment-free lives, even those who advertise otherwise. Those who try are destined for disappointment. A commitment-free life is a life without relationships, meaningful work, or a greater sense of purpose, as David Brooks has argued. We live lives of purpose and meaning by carefully choosing commitments that align with our values, and then leaning into those commitments with everything we have.

That means each of us lives in the tension between commitment and retreat. At times we give to people, projects, or causes outside ourselves; at other times we draw inward for times of refreshing. Each of us lives this balance differently, and different times and seasons of life call for re-adjustment. Rather than marketing escape, I’d much rather ask: how can real people best inhabit this tension between our commitments and our dreams?

—After all this, I’m almost embarrassed to admit that I’ll be living in a van for the next three weeks. Not just any van, but a really nice borrowed van, with solar panels and a stove and a sewer tank and every other amenity. Yes, I’m excited. Yes, I’ll post pictures on Instagram. Yes, I feel like I’m stepping into a dream, which is only possible because I’ve had opportunities and good luck that many people don’t. I feel both grateful and sheepish.

But I’m still that man in Donald Justice’s poem, standing between the dreamy woods and his mortgaged house. My air conditioner is still inoperative, and I spent a frantic day coordinating with HVAC service technicians from an American Airlines flight somewhere over the Rocky Mountains. I’m worried about my pets in the sweltering heat, and the gargantuan repair bill. I’m worried about my kids, who are currently on a plane to Africa. I am enjoying this quite moment on a patio, writing, but in a few minutes I’ll need to go deal with a litany of travel-related logistics. I’m also clear-eyed that these three weeks do not constitute my new life, but rather an interlude before I willingly embrace my next set of professional commitments.

But this is good. This is life as it is supposed to be, in all its multi-dimensionality. I don’t think Donald Justice was being prescriptive; he was acknowledging the tension each of us inhabits.

June 16, 2024

Day 0: A Hopeful Wilderness Journey

For the next three weeks, I will be blogging about my post-military retirement trip to the Sierra Nevada mountains. This first post explains the project. You can subscribe to my blog posts here (it’s free) and follow my author page on Instagram.

“Midway upon the journey of our life I found myself within a forest dark, for the straightforward pathway had been lost.”

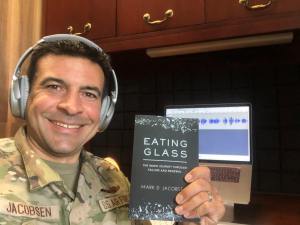

So begins Dante’s Inferno. The lines are quoted in almost every book I’ve read on midlife; Dante’s description captures the midlife passage with archetypal power. The Forest Dark. I personally spent years in that dark wood, that “forest savage, rough, and stern”, wondering how I got there and how I might get out again. I describe much of that journey in my book Eating Glass. I write about wilderness experiences, of deserts where prophets are forged, of hard lessons about acceptance and the release of control.

Dante’s Forest Dark is not a place we seek, but rather one we sleepwalk into. Dante describes himself as full of slumber “at the moment, in which I had abandoned the true way.” In midlife, we confront all the ways we have abandoned our true self. The dreaded forest gives a gift: consciousness. We wake up to life.

Yet there is another tradition of wilderness passages: the journey consciously chosen, the voluntary exile, the compulsion to lose and then discover oneself. The forest becomes a place to find wisdom, to train, to prepare for the next ordeal. The traveler is explorer and pilgrim.

—My upcoming three-week trip to the Sierra Nevada mountains is, I hope, in the latter category. I’ve already done my time with Dante, trudged through the hellscape of my own Inferno. Professional setbacks and a sense of lostness. Divorce. Learning to date again, feeling it go sideways. Supporting my children through the upending of their lives.

Now I’m on the other side of that first wilderness journey. I’m in a loving, healthy new relationship. Recently, while sitting around a campfire after a day of climbing and rock-jumping at a remote swimming hole, my children told me they are happy. It has been a really good year, they said, making an implicit contrast with the damnable year before. Professionally, it was a good year too. I ended my Air Force career in exactly the right teaching assignment, passing on everything I’ve learned about defense innovation to a new generation of entrepreneurs in uniform

Now it’s time for a more joyful kind of wilderness journey.

My years in Dante’s wood woke me up, taught me to listen. I read such good books during those years: about the soul, and unlived lives yearning for expression, and subconscious energy breaking through the surface with violent ferocity. Something within me is trying to be born.

I’m at a crossroads: down one path lies safety and stability in a continued government role, at the price of sameness. It’s a good path. Many of my colleagues choose it, for good reasons. But I’ve learned to trust my energy, and the compass needle points elsewhere. I need a new beginning, new challenges. A reinvention.

—I train hard in the weeks leading up to my wilderness trip. Older people remind me that I’m not old, but when I was young, 44 looked positively ancient. In any case, the wear and tear is getting real. A partly-failed shoulder surgery patched up some damage but also left me with a torn rotator cuff and a long rehabilitation process. I’m still getting strong again and testing my limits. I run and climb stairs. The better my fitness, the greater the adventures I might enjoy.

I’m also helping Hannah get ready. Before we met, she had never climbed–only dreamed of it. She devoured climbing documentaries, which is what brought us together in a chance coffee shop conversation. My friends and I had her on a rock wall just a couple weeks later. A year on, she’s making her first outdoor lead climbs and I’m teaching her multi-pitch climbing skills at mock belay stations in my garage. Also, we’re dating–another subplot in this great division of my life into Before and After.

We spend our last weekend in Alabama climbing at Sand Rock, our local crag, practicing multi-pitch skills on stubby rocks that probably don’t even need ropes. We move slowly, meticulously, practicing every step of our belay transitions until they’re perfect. Better to work out the kinks here, ten feet off the ground, than five hundred.

Our upcoming trip is supposed to be a joyful retreat, but as it draws closer, I feel immense pressure. Three weeks in the mountains is exceedingly rare for me, made possibly only because my children are overseas with their grandparents. I want my trip to count. I want it to mean something. It feels like my life depends on it.

—Life typically progresses in a continuous line. That line makes great big ups and downs, and sometimes careens in wild drunken loops, but the pen never lifts from the page. Each event sets the stage for the next. Skills compound, networks expand, we progress through adjacent jobs and friends. Momentum carries us downstream like a river, until one day…

“I felt like I was living someone else’s life.”

That’s another recurring line in books on midlife. One day, many of us wake up to realize we have abandoned something precious in ourselves. We could have everything in the world going for us, and yet we crave some kind of renewal.

That’s the puzzle I’ve been stuck on: how to lift the pen from the page. How to create a discontinuity.

Everyone in my professional life knows me as a defense innovator. That is true. I am a defense innovator, and I will still be a defense innovator when I descend from the mountains and begin my next job in a defense technology startup. I’m excited about an amazing opportunity ahead.

But I’m something else too. I’m a writer, with a deeply spiritual nature and a profound love of the natural world. I use words like “soul” and “belonging” that don’t compute in my professional circles. I read books by psychotherapists and meditations on landscapes. I use precious vacation time to make pilgrimages to Thomas Merton’s monastery and Wendell Berry’s town in rural Kentucky. I write as a way of perceiving, experiencing, and understanding the world. So much of my writing is an effort to answer my own biggest questions: how does one construct a well-lived life? How does one find a sense of belonging in the world? How do we reconcile our deepest human needs with our dehumanizing technological society?

I never really harmonized my personal writing with my military career, which is one reason I finally felt compelled to hang up the uniform. Military leadership demands a certain persona, especially as one advances through the ranks. The kind of writing I like to do demands almost the opposite qualities: a penchant for solitude, an inclination for observation over action, a temperament that asks hard questions rather than provides confident answers, a willingness to distill life experiences into narrative rather than bullet lists.

Collisions came with increasing frequency. The Air Force wanted and needed the Colonel, so I kept the writer quiet.

Now it’s time.

—So: military retirement. An interlude. Three weeks around Donner Pass, Yosemite valley, Tuolumne Meadows, and Bishop.

On the surface, it’s about getting outdoors for a few weeks. But it’s really about personal reinvention, which is very hard to do. It’s difficult enough overcoming twenty-two years of career momentum and social expectations. What makes this even harder is that I’m taking myself with me, with all my habits, self-doubts, and distractibility.

My strategy is this: for the next three weeks, I am going to live as that alter ego. No defense innovation. No coding. No military persona. No responsibility, real or perceived, to write the way a Colonel or technologist is supposed to write.

Instead, I will give that other persona free expression. I am attempting to craft a temporary new life, in the same way I might craft a short story. Hannah and I will be living in a van, going where the winds blow. We’re seeking a kind of simplicity, although that will entail its own complexities, like where to empty sewage or do laundry. My reading list encompasses soulful nature writing, like Robert Macfarlane’s Landmarks and Kim Stanley Robinson’s The High Sierra: A Love Story, and rich psychology books like Rollo May’s Love and Will. I am a do-er and Hannah as a be-er, so I expect our days to exhibit a healthy fusion of our natures: leisurely hours sitting in beautiful alpine landscapes, and rigorous hikes or ascents of rugged rock faces.

And writing. Writing, writing, writing. That is the heart of it all, my real motivation, the thing I’m trying to set free. I’ve spent two decades feeling wound up too tight, worried about readership and positioning and branding. I’ve never felt comfortable making the leap into writing because I don’t have a business strategy. Walt Whitman said, “I contain multitudes.” That celebration of eclecticism resonates powerfully. It’s a great way to live and a terrible way to craft a value proposition to buyers.

Enough of all that. My goal, in these three weeks, is to let go of that need for control–to live lightly upon the earth, to write for the love of it and for no other reason. I will write for myself.

And then I will share it.

Thats the catch, the terror-inducing crux of this long ascent. I’ve always had a paralyzing fear of sharing my personal writing, especially if I haven’t spent weeks rigorously editing and polishing. That has held me back for two decades. So my commitment, for these three weeks, is to write what I want and then share it. Whether anyone reads it, likes it, or hates it doesn’t matter. It’s all flint on steel, a shower of sparks, the hope of igniting something.

I only have a small readership, and I expect I’ll shake some of you loose, especially those who came looking for defense innovation writing. That’s fine; no hurt feelings. I’ll do more of that writing later in other forums. But I hope I’ll gain a few new readers as well. I give you absolutely no promises concerning what I will write about, except that it will be important to me. You can subscribe to these posts by e-mail (it’s free) and see shorter updates on Instagram. If this is too much, you can unsubscribe below or–better–switch to an infrequent newsletter, so you’ll know when I release new books.

What will happen after those three weeks? That’s a three-weeks-from-now problem.

June 12, 2024

“The Weight of Oceans” at Asimov’s SF

It’s been a long time since I’ve checked in here, but I’m delighted to announce that my new short story “The Weight of Oceans” is now available in the July/August 2024 issue of Asimov’s SF. You can subscribe through the website or find the issue in major bookstores.

It’s great to be published in Asimov’s again. I have a long history with the magazine, beginning with my receiving the Dell Award (known as the Asimov award in my time) for my writing while at USAFA. It only took me 20 more years to finally get published in Asimov’s, with my 2023 story The Repair.

It’s funny… I generally approach writing stories like an engineer or carpenter. I brainstorm ideas, sketch out characters, develop initial plotlines, and then set to work writing. The story always takes on a life of its own, but this initial engineering work provides a kind of scaffolding that gives the story shape. I’ve written many stories this way, but the only two stories I’ve sold to Asimov’s began with a completely different approach. Both originated as unplanned “freewrites”, in which I simply sat down with a notebook and started scribbling out a scene. With “The Repair”, I wanted to try writing a single cyberpunk scene. I had no plan for turning it into a story, nor any idea where that first scene would lead. Only over time did I discover what the story was actually about. It was a humbling and almost frightening lesson about the power of the unconscious to guide creativity.

“The Weight of Oceans” had even less thought behind it; I sat down to freewrite to warm up my creative muscles. Somehow, the image came to me of two women in a bar fight. I was in a fiesty mood and ran with it. The words kept flowing. I’d recently been telling a friend that the zeitgeist of contemporary science fiction often involves strong independent characters standing up to soulless and abusive capitalist machinery, so I decided to try taking this story in that direction. It was tricky, because as a military officer and political scientist who reveres capitalism’s achievements even as I detest its faults, I hold a much more nuanced view than many other SF authors do. Fortunately, I was pleased with the story that emerged. There was a particular moment during revisions when my impression went from “this is really weak, but I should just see it through” to “wow, this is actually pretty good.”

Ultimately, this story explores the common feeling that the world’s challenges are bigger than we can comprehend or manage. It asks how we can find hope and agency, when we are holding back… THE WEIGHT OF OCEANS.March 22, 2023

“The Repair” at Asimov’s SF

Twenty-two years ago, as a college sophomore, I took 1st runner up in the Dell Award for Undergraduate Excellence in Science Fiction and Fantasy Writing (then known as the Asimov Award). Sheila Williams (the editor of Asimov’s Science Fiction magazine) and Rick Wilber flew me and the other finalists out to a writing conference, where I sat by the pool and talked writing with Joe Haldeman, Sean Stewart, Kelly Link, Charles Sheffield, Nancy Kress, Daniel Keyes, Ted Chiang, Octavia Butler, Brian Aldiss, Neil Gaiman, and many others. The next year, I won the contest and went back. These were life-changing experiences for a young person with only distant dreams of being a writer. I realized that “making it” was well within reach and began submitting stories, without success.

I got busy after that, with my Air Force career and a young family. Writing came and went. In 2020, amidst the pandemic and a transition into a teaching job, I committed to writing more seriously. It has only taken 22 years, but with “The Repair,” I finally made it into Asimov’s.

The story began as an experiment, as I tried to stretch my usual style and write a cyberpunk tale with the atmosphere of Blade Runner. It took on a life of its own and grew into a commentary on cancellation, asking that classic speculative fiction question: “What if this continues?”

Asimov SF’s blog also ran an interview with me about the story.

I’m a little late getting this post up, but you might still be able to find the March/April issue on the shelves at your favorite bookstore. You can also order it at www.asimovs.com or purchase the digital issue via Amazon Kindle. Even better, you can subscribe!

May 25, 2022

My new article on prospects for drone delivery in Ukraine

I have a new piece out at War on the Rocks, titled The Dubious Prospects for Cargo-Delivery Drones in Ukraine. It draws on my 2014-2015 effort to develop a siege-breaking capability for Syria.

This was a tricky piece to write. As an innovator, I believe few things are impossible and I always want to encourage people who try hard things. I also earnestly want to see this paradigm realized. At the same time, two years in the trenches taught me just how hard the problem set is. If we want to build a capability like this, we need to be clear-eyed about the challenges that must be overcome. We must also invest properly in the requisite capabilities and organizational capacity.

I hope this piece will drive some healthy conversation and lead to much-needed investments in last-mile battlefield logistics.Coincidentally, Walmart announced yesterday a significant expansion of its experimental drone delivery service. The timing meant that I wasn’t able to comment on this development in my article. However, I think it reinforces my core message: that developing a scalable drone delivery paradigm requires tremendous organizational capacity and expertise. Walmart has been building this capability up over years, in partnership with companies experienced in drone delivery. They originally started in a single small town, use certified human pilots, only deliver to locations within 1.5 miles of participating stores, and require control towers to maintain visual line of sight with their drones. These are promising developments, but a model like this can’t easily be replicated from scratch in a warzone like Ukraine.May 24, 2022

What I Learned Self-Publishing a Book, One Year In

Friends often ask me how things are going with my book, Eating Glass: The Inner Journey Through Failure and Renewal, which I released in March 2021. For those unfamiliar, the book aims to help readers navigate the aftermath of a failure experience and find new life on the other side.

In this 5000+ word mega-post I’ll share some reflections, which might be relevant if you’re curious about my process as an author, curious about the book, or want to know what it’s like releasing a book of your own into the wild. There are no secrets here; I’ll share the good, the bad, and the ugly. I’m not claiming to be an expert; you should look elsewhere to learn about marketing. But based on data I’ve seen, my experience is pretty typical, especially for a newer self-published author.

Publishing this book was one of the most rewarding experiences of my life, but it’s extremely rare for a standalone book to gain financial success or a significant readership without being part of a much larger strategy. Eating Glass has consistently received glowing reviews from readers. Sales, however, have been lackluster; I’ve sold around 500 copies, mostly to people who know me. I knew this would be a difficult book to market but it hasn’t gained traction in any of the niches I expected it to. I will admit that I have not been nearly aggressive enough in marketing it, but it seems like every marketing attempt I’ve tried has failed to yield significant returns. I’m still trying to crack that code.

Fortunately I am being compensated in other ways—in deeply personal emails and phone calls from people who were moved by the book in the best possible way. The book had exactly the impact I hoped it would, on the people who needed it.

As I forge ahead, I’m doing three things: (1) Doing my best to not let the low sales get me down (2) Cherishing the positive feedback and (3) Putting on my entrepreneur game face, studying what’s working and what’s not, and taking pragmatic lessons on how I need to grow as an author-entrepreneur.

The Road to Publishing

I should back up and talk about my goals for the book. Eating Glass began as a series of cathartic reflections I wrote purely for myself, while navigating the aftermath of a startup failure. Over time, I saw the potential for turning them into a book that could help others. Even so, I agonized for months over whether or not I should publish such a vulnerable book. Maybe I was oversharing. Maybe I was in too raw of a place, and would look back on my experiences later with different eyes. Maybe I’d damage my reputation. Maybe the vulnerability on display would make others cringe.

I should back up and talk about my goals for the book. Eating Glass began as a series of cathartic reflections I wrote purely for myself, while navigating the aftermath of a startup failure. Over time, I saw the potential for turning them into a book that could help others. Even so, I agonized for months over whether or not I should publish such a vulnerable book. Maybe I was oversharing. Maybe I was in too raw of a place, and would look back on my experiences later with different eyes. Maybe I’d damage my reputation. Maybe the vulnerability on display would make others cringe.

In the end, I chose to publish two reasons: first, I was tired of being afraid, and needed to fully embrace my own journey. As I’ve written before, publishing the book was one of the most empowering experiences of my life.

Second, I wanted to help others. I wrote the book that I wish existed when I was struggling. Nobody, to my knowledge, had written anything quite like it. I also knew that I was hardly alone in my journey. I periodically read reflections from failed founders and other high achievers who suffered soul-shattering experiences. I knew the book would speak to them.

In the end, I wrote this book for people who needed it. Even if the world at large found the book mystifying, I would be satisfied if it spoke to the audience that needed it.

Positioning a Book About FailureOnce I made the decision to release the book, that still left numerous tactical decisions. How would I publish the book? How would I position and market it?

These were hard questions. I wanted to create an artistic masterpiece, but the tension between artistic quality and commercial felt real.

Too many artists blow off the business side of writing, and then pout when they don’t sell. I made this mistake with my self-published military SF novel The Lords of Harambee, which I’d spent a decade writing. I still think it’s a good book—certainly better than a lot of what gets published—but I only sold around 250 copies. I largely have myself to blame for that, because I designed my own cover (a huge no-no) and did almost no marketing.

My 2012 military SF novel.

This time, I wanted to set my book up for success. I researched extensively. I tried to get smart on balancing artistic integrity with commercial sales appeal. (For what it’s worth, Ryan Holiday’s Perennial Seller is the best I’ve found on this).

Still, this is a hard balance to strike. I repeatedly found myself facing decisions that would probably increase sales but undermine the book’s artistic integrity.

For example, the market is full of books with titles like “Fail Your Way to Success” or “Fail Big: Fail Your Way to Success and Break All the Rules to Get There.” If I ran market surveys or A/B testing to arrive at a title, the market would ask for more of the same. This is how you convince people to read a book about failure—by appealing to the deep, human thirst for guidance about how to succeed beyond your wildest dreams.

But this branding trivializes the painful reality of failure, which is the core of what I wanted to write about. Eating Glass was in many ways a reaction against this genre of pep talks. I designed every part of the book to convey to the reader that we would embark together on a serious, thoughtful journey through the underworld of a high-achieving life… from the title to the black matte cover with cool colors to the phrase “inner journey” in the subtitle. The word “renewal” promised an arrival and an inner transformation, but also suggested it would be subtle, perhaps wiser, and perhaps not quite like the “success” other titles promise.

If I was optimizing for commercial success, I also would have replaced Eating Glass with multiple smaller books targeted at different niche audiences. I would have written one short, practical book specifically for failed entrepreneurs and another for struggling graduate students. By focusing on niches, both would probably have outsold Eating Glass. But I was after something larger—a commentary on the universal human journey, with all its ups and downs, which spans an entire life through all its stages. The book’s most important but subtle themes, about growth from “first half of life” concerns into “second half of life” living, would have been lost.

In the end, Eating Glass is exactly the book I wanted it to be. I refused to compromise my vision for the book, but I was clear-eyed about the consequences of my choices. Eating Glass would probably not be a commercial success, but I hoped that it would be a hidden treasure for those who did read it. I hoped that struggling high achievers would pass old, dog-eared copies around when they met someone else walking a similar path. They would say, “Dude, you need to read this.”

Traditional vs. Self-PublishingMy next decision was about how to publish. I believed Eating Glass was high-enough quality to traditionally publish, so I put months of effort into writing a proposal, building a marketing plan, and sending query letters to literary agents. I built a platform—to include my website, blog, and mailing list—so I could show publishers that I was serious about helping Eating Glass reach readers.

I sent roughly a dozen query letters, in two batches separated by a couple months. A few wrote back form rejections, typically one or two months later. Many never wrote back at all.

This is pretty typical, and a dozen agents is not a large number. Authors routinely have to query far more than that, for far longer, before they get a lead. Becoming a writer takes a thick skin. With that said, I found this process infuriating, dehumanizing, and borderline abusive. There is no reason an agent or publishing house can’t take twenty seconds to send a form rejection letter, instead of leaving an author on the hook for months, until their hope slowly fades and then dies. The fact this is considered acceptable testifies to the power imbalance between writers and the publishing industry, and the desperation of most aspiring authors to be published.

I already have some deep life wounds related to rejection, so pitching a vulnerable book like Eating Glass wasn’t easy. The rejections (and silences) felt like a referendum on my life. I knew this dynamic would get even worse later, because even if an agent agreed to represent the book, I’d face another round as the agent pitched to publishers. The process would take years. And unlike most nonfiction books, which are sold based on a proposal and outline, Eating Glass was finished.

The more I researched and learned about the industry, the less sure I felt about the benefits of being traditionally published. Most of us view books through the lens of “survivorship bias.” We only know the books we see on the shelves at Barnes & Noble or on Amazon bestseller lists. The vast majority of traditionally published books never reach those shelves, or attain any level of fame at all. Furthermore, everything I’ve read says that in today’s world traditional publishers largely rely on authors to do their own marketing—and won’t even consider publishing your nonfiction book unless you already have a following of thousands.

After a few months of playing this game, I had to think carefully about my goals. I was frustrated and annoyed at the process. I had no desire to wait three years to hold a book that was ready for publication today. The agent dating game only fed my sense of rejection, when what I really needed to move forward was to embrace my story, get it out into the world, and move onto a new writing project. Furthermore, I was spending a huge amount of time building my own marketing plan. If a publisher wasn’t going to do much other than tell me to execute my own plan, why would I give them the lion’s share of my royalties?

What I really wanted was creative autonomy, agility, and the ability to tell my story the way I wanted. Self-publishing appeared increasingly attractive—not as a second-rate alternative to traditional publishing, but as a creative choice that gave me full control over my artistic vision and allowed me to work with agility and speed.

Self-publishing has become highly professionalized in the last few years if you do it right. James Altucher argues that the critical distinction today is no longer between traditional publishing and self-publishing, but between professional and unprofessional publishing. What he calls “Publishing 3.0” entails professional author-entrepreneurs leveraging freelance designers, editors, etc. to professionalize the self-publishing process.

I likely had enough access to my target markets—entrepreneurs, graduate students, creatives, and other high achievers—to reach them on my own. However, this would put a huge burden on me to market the book. Nobody would know it existed unless I told them.

Releasing the bookIn keeping with Altucher’s philosophy, I tried to self-publish Eating Glass in the most professional way possible. I hired a professional cover designer through Reedsy. The result was amazing and exactly what I’d hoped for. I did deviate from best practices by doing my own editing and typesetting, but these are areas where I already felt strong, and I still relied on a team of early readers to provide feedback. I went through multiple rounds of paperback proofs from Amazon KDP. When everything was ready, I went through the Air Force’s media review process—then released the book in March 2021.

Browsing cover designers for hire at Reedsy

My initial advertising mostly consisted of social media posts on Facebook and LinkedIn and my small mailing list. I figured I would start with friends and family, then start a more intentional marketing campaign later. (In retrospect, I should have had a much more ambitious marketing plan at launch)

Friends and family embraced the book with great enthusiasm. I sold a couple hundred copies during launch week. I received many kind notes and affirmations from friends. After my months of fear leading up to the release, I found this hugely rewarding. Over the next couple weeks, friends texted photos holding their newly arrived copies. Those were priceless.

However, once I exhausted my own immediate network, sales practically stopped. That was hard emotionally but also exactly what I expected; nobody will know a book exists—especially a self-published one—without marketing.

The warm receptionThe good news is that many people who read the book love it. Even as I struggle to sell books, I continue to receive kind, thoughtful notes from readers who feel deeply touched. They see their own experience reflected in its pages. “It’s like you’re reading my journals,” one reader wrote.

What I love is that each of these readers is on an entirely different journey. One recently left Los Angeles after a couple decades failing to build a successful career in the film industry. Another is an incredibly successful professional who struggles with hidden traumas that most people know nothing about. One is recovering from divorce, while another is a military NCO who has been on his own journey of healing from childhood trauma and combat PTSD. Eating Glass spoke to all of them, which is exactly what I hoped it would do. Something in the book speaks to a universal human experience.

For at least some readers, the book also has a timeless quality. One reader emphasized that he would return to the book again and again in his life, trusting he would continue to find new insights. Another reader told me the book now sits on a special bookshelf along with four or five other classics that he returns to continually throughout his life.

These personal notes mean the world to me. I have to think back to my original goal: Even if this book does not sell widely, I wrote it for those who need it. I love receiving individual notes affirming that the book has exactly the effect I hoped for. This is the success I want, although it is a very different metric than we usually think about. It is a metric about touching individual lives, not necessarily selling at scale.

The scaling challengeWith that said, I do want the book to sell widely. I have a message I want to share. I want to touch more lives. I have also invested thousands of hours in writing, with few readers and little financial return. This has entailed considerable opportunity cost, and it would really be nice to earn a return commensurate with my efforts.

However, scaling has proven to be an incredible challenge. I have tried a variety of methods to promote the book but none has made a significant impact. It is entirely possible that I just haven’t tried hard enough on any of these fronts; I will share more on that below. The book is also intrinsically difficult to market.

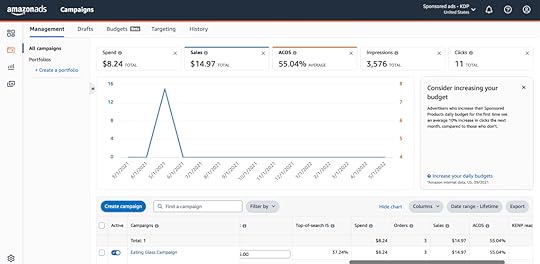

Amazon AdsOne of my first efforts was to use traditional advertising. I tried Amazon ads, which can be carefully targeted. I configured my ads to appear on the pages of books by authors who write on similar styles and themes—like Jerry Colonna, David Whyte, Parker Palmer, and Richard Rohr. I also configured ads to appear on the pages of other books about failure. The ads resulted in very few clicks and no sales. Because I only pay for clicks, and was receiving barely any, I stopped following the campaign. I just checked again, and apparently Amazon shoppers have seen my add 3500 times in the past year, clicked 11 times, and purchased 3 times. I suspect that because my click rate was so low, Amazon’s algorithm stopped showing my ads entirely.

I haven’t looked at this Amazon ad dashboard in a year, but apparently I sold three books a year ago.

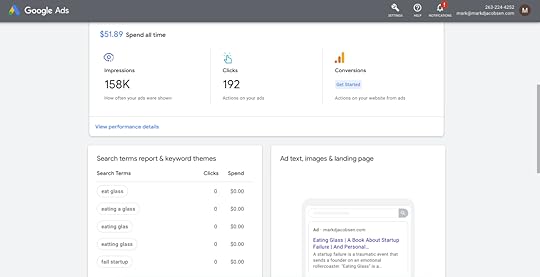

Google AdsLater, I tried using Google ads. I triggered these ads to appear for terms like “startup failure”, “founder depression”, and so forth, thinking these would lead to the exact niche I wanted to target. I was a little amused when, a few days in, Google’s dashboard informed me that most people were finding my ads by googling terms like “can you eat glass.” I did my best to exclude glass-eater terms but I’m not sure this ever fully worked; Google’s ad dashboard is highly opaque. By the time I was done experimenting, 158,000 people had seen my ads and 192 had clicked the link, which took them to my book’s Amazon page. However, zero of those 192 purchased the book.

The minimalist Google Ads dashboard, which didn’t provide enough information for me to determine who was clicking my ads.

A 1 in 1000 click rate didn’t sound unreasonable to me, but the zero sales were concerning. That could indicate two things: (1) something about the product page was turning people off or (2) the people seeing and clicking on my ads were not the people I was trying to target.

Option 1 was a possibility. The cover was (I thought) beautiful and the book had 4.9 stars with dozens of thoughtful reviews. However, the product description was focused on my personal journey. Perhaps that didn’t catch people’s interest? I rewrote the product description to emphasize the universal journey through hardship towards richer, wiser living. The new blurb focused on what the book could do for readers. I continued the ad campaign for another week but still sold no books.

Option 2 looked increasing likely. Maybe the glass-eaters were seeing my ads, not startup founders; when they realized that my book was not, in fact, a manual for how to eat glass, they bounced. Given that I was losing money on each click, I shut down the campaign.

BloggingI initially hoped my blog would gain readership if I shared blog posts on Facebook or LinkedIn, but almost every post only receives 1-2 likes. My suspicion is that the algorithms on these platforms significantly downweight posts that link to articles on external sites.

Blogging is hard work and it can take years to build a following. I have no doubt that if I blogged three times a week for years, I could build a following of thousands. The problem is that this becomes almost a full-time writing commitment, and what I really want to do is write books, not blog posts. The most successful blogs also have a tight focus on a specific theme, but I like to write across a range of interests—a common situation that prevents many aspiring writers from finding commercial success. My difficulties resolving these tensions have been the hardest aspect of trying to launch a writing career, and explain my erratic presence on the blog and social media.

Guest PostsGiven the small size of my own readership, I experimented with writing guest posts for other blogs with large readerships. For example, I am friends with the editor of From the Green Notebook, a wonderful blog about leadership and personal growth, which has over 17,000 email subscribers and a large social media footprint. I sent him a free copy of Eating Glass, which he read, loved, and reviewed on his mailing list. He also gave me the opportunity to write two different posts for his blog and mailing list. The net result of all this activity was around 10 book sales.

I also wrote a lengthy article for Failory, a site that specifically shares resources about startup failure. This is as close to my target niche as you can get, but I sold zero books after the article went live.

PodcastsI’m pretty good at connecting with live audiences, so webinars and podcasting seemed like a great way to draw people into my story. I did a book launch webinar with the Defense Entrepreneurs Forum and have done ten or so podcasts so far. The webinar drew perhaps 10 people, about half of whom were family.

Some of the podcasts presumably reached hundreds or thousands of people. Each of these engagements was a positive, intimate, and heartwarming experience. My podcast hosts loved my books, and we had sincere, authentic conversations. However, after the release of each podcast episode, I typically only sold a few books.

Forum ParticipationI have also actively engaged in relevant startup-centric forums for discussions about startup failure, impostor syndrome, burnout, and other themes my book addresses. The primary site I monitor each day is Hacker News (incidentally, my favorite place on the Internet), where a lot of entrepreneurs hang out. In addition to talking about coding, the site features surprisingly frequent and rich conversations about how to construct a well-lived life.

There is a danger of coming across as sleazy and self-interested in forums (repeated posts that say only “buy my book!”) so I have tried hard to make each post value-adding. I personally address the original poster’s issue, share a link to a free chapter, or even offer to send a free copy of the book to the original poster. When a conversation about loneliness appeared on Christmas, I wrote a post making the e-book free to anyone who wanted it for 48 hours.

I have similarly reached out to strangers on Facebook in groups focused on graduate student mental health.

Each of these engagements typically yields between 0 and 2 sales.

HackerNews also has a feature called “Show HN”, which allows users to showcase new creations that might be of interest to other HN members. These posts can go viral, generating a windfall of interest and support for compelling projects. I thought “Eating Glass” could do quite well, given the composition and interests of the readership. I spent weeks preparing my website with abundant free content. Unfortunately, my “Show HN” post failed to gain any traction and was swept downstream immediately. I sold no books.

Releasing an audiobookThe best thing I did for Eating Glass after its original publication was record an audiobook version and release it on Audible. Although not really a form of marketing, it created a second product that made the book accessible to those who might not have time to read. In a few months I have sold more than 100 copies of the audiobook.

Recording and post-processing my audiobook with Audacity

I recorded the audio myself. In keeping with Altucher’s philosophy of professional self-publishing, I spent considerable time researching quality microphones, tweaking settings, and setting up a recording space with good acoustics. By the time I had finished, I’d recorded every chapter two or three times to get the level of quality I wanted. I also did extensive post-processing, using automated filters and then doing the manual, painstaking work of removing breath noises and lip smacking.

The learning curve was steep, but in the end, I think the book sounds terrific. Listeners have commented on its professional quality. Now that I’ve done it once and developed a workflow, it will be much easier to do again for future projects.

Hitting my networksPart of my marketing plan was to reach out to networks I’m a part of, such as my high school alumni network, the USAFA alumni network, and a large national security listserv that I’m a part of.

My messages to the alumni networks led to a decent number of sales in the first weeks, probably all from people who personally knew me.

As for the national security listserv, the moderator loved the book and enthusiastically recommended it to the entire list. Net result? Possibly 1-2 sales, along with a personal email from one member about why most members of a national security-focused group would never read a book about personal reflection.

Personal outreachMy biggest line of effort has been reaching out personally to individuals who I think might like the book and sending them a free digital copy. When that didn’t yield the results I’d hoped, I switched to mailing physical copies along with handwritten notes on elegant, personalized stationary.

I have written to numerous failed founders who have taken the brave step of writing publicly about their experiences. I have written to venture capitalists who run mental health programs for their founders. I have written to psychologists who specialize in entrepreneur mental health, and CEO coaches who specialize in vulnerability. I have written to authors I cite and podcasters I listen to.

I like doing this kind of advertising more than anything else, because it is far more personal and feels more like a mutual exchange. I am writing people I respect, whose work I have read and loved. However, it can also be the most demoralizing form of advertising, because the rate of engagement still remains low, even among people I thought would absolutely love the book. I suspect the vast majority of these people are simply busy and overwhelmed. For every 20 notes I send, I might get two or three polite dismissals and one lead.

The rare winsThe key words here are “one lead.” That seems to be where the magic is found. I mentioned earlier that I put a great deal of work into reaching a friend’s mailing list of 17,000 but only sold 5-10 books. One of those 5-10 people was an Army NCO named Mike Burke who runs a podcast called Always in Pursuit, about leadership and vulnerability. He is the guy who now keeps Eating Glass on a special shelf with his other classics, and he quickly reached out to arrange a podcast interview. He now shouts about Eating Glass from the rooftops, so I sent him a box of free books to give away. I, in turn, get to tell you about how much I love his podcast and the way he is inspiring more authentic, introspective leadership in his listeners.

His enthusiastic support for my book led me to a few other supporters, each of whom led me to more. Compounding interest is at work here, but I have to fight for it aggressively.

Some of these leads have also led to enjoyable moments of connection. Dr. Michael Freeman, a psychologist and psychiatrist who focuses on startup founder mental health, read the copy I sent and sent a nice note. So did Dierdre Wolownick Honnold, a rock climbing hero I discuss in the book (although, embarrassingly, she informed me I’d made a couple factual mistakes when I told her story… another lesson learned, about fact-checking during editing).

Even as I consider how to generate more sales, I try to stay focused on these interpersonal relationships. I have to remind myself that Eating Glass achieved my original goals, and that each of these one-on-one moments of connection is its own reward.

My LessonsWhere do I stand today? A year after publishing Eating Glass, I have sold around 400 books and just over 100 audiobooks. I continue to sell 5-10 copies a month. People who read the book seem to love it; it has 4.9 stars on Amazon and receives heartfelt praise, but getting people to read it often feels impossible.

It is easy to get discouraged. This is the point where many writers quit, but the writers who succeed mine their experiences for lessons, learn, and get back to work. So what can I learn from all this?

As a writer, I have the privilege of making my own choices… but I also live with them. Eating Glass is exactly what I wanted it to be. I did not compromise my artistic integrity in creating the book I wanted. I knew from the start that I was making choices that would hurt its commercial viability, but I also knew it would speak deeply to the audience that needed it. Both predictions proved to be true.I think ‘failure’ is a negative emotional trigger. The science around advertising is fascinating. A single word can activate powerful subconscious forces that lead a consumer to buy or avoid a product. I can’t prove it, but I now strongly suspect that the word ‘failure’ is a negative emotional trigger that most consumers recoil from.Marketing experts are right: work that doesn’t fit neatly in a genre is a hard sell, and memoir is among the hardest genres to sell. Eating Glass sits between a personal growth book and memoir. That ambiguity enriches it but also makes it hard to position. Also, I may have branded it too much as a memoir. What’s become clear is that selling memoirs is hard, because people are most inclined to read memoirs of celebrities or people they know personally.Writers must fight for every reader. When I was running my nonprofit, an advisor who had expertise in fundraising told me that he had to court each individual donor personally, no matter how big or small their donation. That advice stuck with me. It’s tempting to wait for a magic bullet that will generate waves (Brené Brown, if you’re reading, you’re welcome to endorse my book!) , but most writers need to fight for the heart of every reader. Even if I’m only selling 1 or 2 books each time I engage with an audience, I should embrace that audience.Exponential growth is slow in the beginning. Almost every writer has to slog their way through years of slow growth before they reach a bend in the curve. This is normal. Breakout writers keep putting in the work.Writers need to be persistent and aggressive in marketing. I have admittedly fallen short here. I tend to market in intermittent waves, rather than maintaining a consistent pace. Successful writers spend as much time managing their business as they spend actually writing. This is my biggest growth area as a writer. It’s not too late for Eating Glass; there is a lot I still need to do.Building a writing career is a strategic enterprise that plays out over years. Writers often say that your next book is the best marketing for your current one. If you build a readership over years, hungry readers will look to your backlist. Professional writers to continually produce new work in order to grow a career. I won’t be able to assess the performance of Eating Glass for years or decades.Lessons for OthersReaders who have made it this far, and are considering publishing their own book, should know that my experience is pretty typical. According to Scribe Media, the average self-published digital only book sells roughly 250 copies in its lifetime. The average traditionally published book sells 3000 copies. These are not large numbers.

This doesn’t mean you shouldn’t publish a book; you should!

It just means that you should have realistic expectations about what publishing a book will or won’t do for you. A standalone book probably won’t make you a fortune or catapult you to fame, but it can serve many ancillary purposes: satisfy your thirst to create, give you pride in a difficult achievement, grow your skills and confidence, help you build relationships with readers, demonstrate your expertise, attract clients or customers to your other business services, or usher you into new relationships and communities.

Anyone considering self-publishing a book should also get smart both about the self-publishing process and the business of writing. One of the best places to start is with Joanna Penn’s website, The Creative Penn.

Once you publish one book, it becomes much easier to write a second. I learned a ton with Eating Glass. I know how to publish an e-book in minutes. I know how to hire freelance cover designers, typesetters, and editors. I know how to obtain ISBNs and make my books available for distributors to major bookstores through IngramSpark. Although I haven’t quite cracked the code on gaining value from paid ads, I know the basics of how to use them. With these skills in hand, publishing a second book will be much easier. I can see how highly productive author-entrepreneurs become engines for continually delivering new books and services.

In ConclusionIn summary, releasing Eating Glass was a milestone for me. It was one of the most empowering experiences of my life, and I love knowing that I have touched at least a few lives through the magic of writing. However, publishing a book is only one milestone in its journey, and it’s an even smaller milestone in an author’s career. I have to continually navigate feelings of hope, disappointment, and exhilaration, even as I have to keep doing the hard work of connecting the book with the world.

As I consider my lessons learned about publishing and marketing, two stand out. First, creators operate in a realm of exponential math and compounding returns, which is not necessarily intuitive. It is easy to get demoralized when our mailing list grows by 1 person a month, our posts only get one or two likes, or our sales numbers hover near zero. But each additional connection we make links us into an ever-deepening web of relationships and opportunities. As exponential magic goes to work, a rise might come any time. I’m learning that the hard part is staying committed to the work—to producing—regardless of what the numbers seem to indicate.

The second thing I’ve learned is the primacy of individual, personal relationships. That is where I’ve found my value as a writer lately, as I shared in my post about Messages in Bottles. That is what keeps me going. All of us want to make a difference with our lives, so there is no higher pleasure than receiving a note about how my words have positively influenced somebody. As long as I continue to receive occasional notes like this, I know I am succeeding.

The real magic is that these two lessons fit so well together. In a world of compounding returns, it is individuals who matter. A new relationship with a single reader is not merely an additive increment to a sales chart. A new reader is a unique individual with his or her own passions, perspectives, and community of relationships. Each new reader connects a writer to a much broader community and an entirely new web of relationships. That is exhilarating and scary, but it’s also… well, magical.

April 28, 2022

Life in Three Acts: Adventure, Tragedy, Comedy

I recently came across this excerpt from John Williams’ novel Augustus:

The young man, who does not know the future, sees life as a kind of epic adventure, an Odyssey through strange seas and unknown islands, where he will test and prove his powers, and thereby discover his immortality.

The man of middle years, who has lived the future that he once dreamed, sees life as a tragedy; for he has learned that his power, however great, will not prevail against those forces of accident and nature to which he gives the names of gods, and has learned that he is mortal.

But the man of age, if he plays his assigned role properly, must see life as a comedy. For his triumphs and his failures merge, and one is no more the occasion for pride or shame than the other; and he is neither the hero who proves himself against those forces, nor the protagonist who is destroyed by them.

Wow, that landed. Life in three acts: Adventure, Tragedy, Comedy.