Mark D. Jacobsen's Blog, page 6

November 7, 2020

What I’m Reading: October 2020

The cover images below are hyperlinks through Amazon’s affiliate program. Purchasing through them will provide modest support to this site.

The Startup Community Way: Evolving an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem by Brad Feld

[image error] [image error]

Last month I read Startup Communities by venture capitalist Brad Feld. Only after I read the book did I realize that Feld and coauthor Ian Hathaway had just released this follow-up book. This is a better book, and in many ways a superset of the original. It builds on those earlier lessons, refines a few things, and goes into much more depth.

Like the earlier book, this is a book about creating entrepreneurial ecosystems in specific locations. It is the first book you should read if you are part of a community that wants to create an innovation community. Feld is honest about the challenges in building entrepreneurial ecosystems, but is also optimistic about the prospects of even a small group of committed entrepreneurs to create an entrepreneurial ecosystem.

The book is loosely structured around the science of complex adaptive systems. As someone passionate about complexity science, I was eager to see how they developed this idea. I was a little disappointed that the book did not take the idea beyond loose metaphor, but nonetheless, this is a good book. I am going to incorporate it into the Technology & Innovation course I teach in February, largely because there is so much interest inside government about how to create entrepreneurial ecosystems.

Beyond the Summit by Todd Skinner

[image error] [image error]

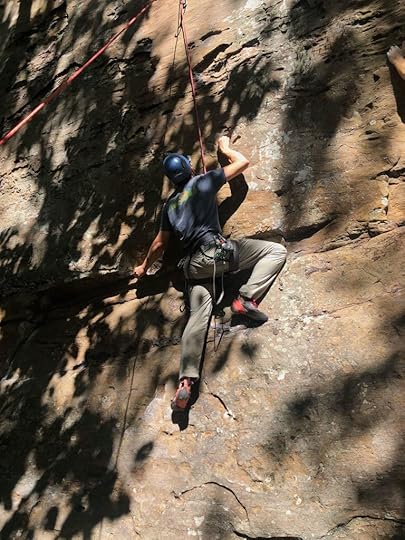

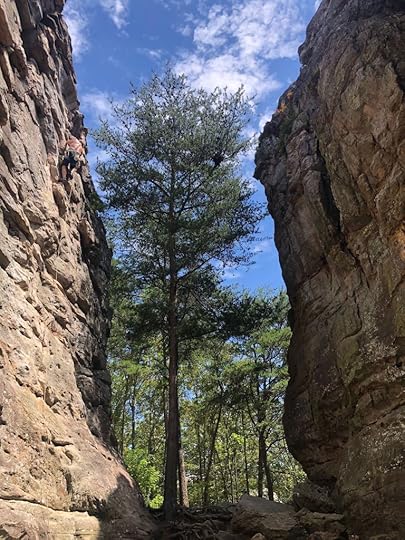

One of the things I love about rock climbing is that it’s such a wonderful training ground for life. It forces you to the edge of your abilities, because progress constantly requires taking one step further into fear and the unknown. Climbing well requires mental focus and self-mastery. Progress is visible and measurable. More than anything, defying gravity to scale a rock wall or mountain is a sublime metaphor for achieving hard goals.

That is why I was intrigued to discover this book by Todd Skinner, a climber legendary for making grueling first ascents that many deemed impossible. The book is marketed to business leaders, with a subtitle about “setting and surpassing extraordinary business goals.” I began reading with some trepidation, because a book framed this way could be either very bad or very good.

Fortunately, I found the book to be very good. Like most business or self-help books, the insights are mostly just conventional wisdom, but sometimes sitting with conventional wisdom is useful; the value comes not from novelty, but from reflecting deeply on that wisdom as one reads a book. The execution in this case is very good. I found myself continually reflecting on how Skinner’s insights might apply to my own life. The book also succeeds as a climbing memoir; Skinner and his team’s hard slog up Pakistan’s Trango Tower makes for riveting reading.

The book should appeal to anyone who liked The Rock Warrior’s Way by Arno Ilgner, one of my favorite books about climbing and life. My enjoyment of the book was marred only by the knowledge that Skinner’s climbing career ended in tragedy, a reminder that a life lived on the edge is not without risk.

Endymion by Dan Simmons

[image error] [image error]

Hyperion by Dan Simmons is hands-down my favorite science fiction novel. It is structured after the Canterbury Tales, with a group of pilgrims each narrating a different tale as they travel to the mysterious Time Tombs on the world of Hyperion. Each tale is masterfully written in a different style and genre, the various plots hinge on breathtaking feats of the author’s imagination, and the characters are rich and detailed. The universe that serves as a backdrop for these stories is vast, complex, and imaginative. These stories all converge in the sequel, The Fall of Hyperion. I recently listened to both on Audible, after reading them twice in the past.

Endymion is set almost three centuries later, following a civilizational collapse triggered by the events in the first two novels. I will not introduce the plot here, because I don’t want to spoil the first two books and you shouldn’t read Endymion anyway if you haven’t read Hyperion and its sequel. I’ll just say that if you have read those two books, Endymion is a worthy sequel. It is longer, slower-moving, focused on a smaller cast of characters on a more intimate journey. Much of the novel follows the key characters as they travel along the River Tethys, a river that spans numerous worlds joined by farcaster gates. That narrative structure aptly summarizes the book; Endymion is a river float through the vast universe that Simmons imagined, with all its diverse worlds, characters, and organizations. If that sounds appealing, check out the series.

The View from the Cheap Seats by Neil Gaiman

[image error] [image error]

I love Neil Gaiman’s stories, so was eager to listen to this collection of essays on Audible. Gaiman reads his own work, and his British-accented storyteller’s voice is a delight to listen to. He is a thoughtful, eccentric, and fascinating person, so I looked forward to hearing his thoughts on wide-ranging topics.

I did not read the product description closely, so had to adjust my expectations when I realized that the book mostly consists of book introductions, with a few speeches, reviews, and essays in the mix. Introductions, after all, are the parts of books that many of us skip (okay, I read them, but I’m a nerd that way). Furthermore, most of these pieces were about books, comics, authors, illustrators, and music artists I was unfamiliar with. For that reason, much of the book’s rich value went right past me.

With that said, many of the pieces did speak powerfully and directly to me. Gaiman’s defenses of books and libraries are charming, funny, and important. I loved hearing about his formative years as a child and young man, haunting libraries all summer and being mugged en route to the comic store with his hard-earned cash. His 2012 commencement speech Make Good Art, one of my favorite speeches, makes an appearance. His commentary on books and authors I have read was wonderful. I loved his piece about the dramatic impact of C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and G.K. Chesterton had on him; his reverence for Lewis is fascinating and countercultural, because he does not share Lewis’ Christian worldview. The conversations he relates with Stephen King are rich and funny, made even funnier by his Stephen King impersonation. His pieces about classic science fiction, fantasy, and horror authors helped me put them into a broader context of how those genres developed.

Many of the other pieces did not speak quite as directly to me, but I still found much to appreciate about them. Gaiman’s mastery of his craft shows through every essay. His language is simple, clear, and direct, which is a testament to his care and precision. He is good-natured, funny, and always able to see the goodness in a wide range of artists and their work, even their not-very-good work, which is part of their lifetime trajectory of becoming good artists. Most significantly, every piece in this collection demonstrates Gaiman’s lifelong commitment to storytelling. The collection might seem narrowly focused on specific creators and their creations, but that is because artistic creation is Gaiman’s entire world. That’s what makes him so good.

Power to the People by Audrey Kurth Cronin

[image error] [image error]

Audrey Kurth Cronin is a terrorism scholar who made a name for herself with her book How Terrorism Ends: Understanding the Decline and Demise of Terrorist Campaigns. I somehow stumbled across her new book Power to the People while looking for new books to round out the Technology & Innovation course I teach at SAASS.

I have only had time to skim the book at this point, but have already decided to include it in this year’s course. My course is built around complexity theory and emphasizes the reciprocal relationship between new technologies and social structures; we see many examples historically of how seemingly small technology changes can radically shape how human beings organize themselves economically and politically. I wanted a book that carried this idea forward into the future, particularly as non-state actors gain access to cutting-edge new technologies.

Cronin’s book looks like a great fit because she demonstrates how the proliferation of two technologies–dynamite and the AK-47–“inadvertently spurred terrorist and insurgent movements that killed millions and upended the international system.” After examining these cases in depth, the book examines emerging technologies like small drones, which I believe can have strategic impacts.

Solaris by Stanislaw Lem

[image error] [image error]

I wrestled with how to approach this review, because I feel a bit guilty. Solaris is a book that I should love. It is a science fiction classic. It is admired by some of my favorite science fiction authors. It is cerebral, intelligent, haunting, and philosophical, traits I generally like in books.

There were stretches of the book that captivated me. The story follows a scientist named Kelvin who travels to a research station on the strange, oceanic world of Solaris, and begins seeing haunting apparitions from his past. The suspense is subtle and psychological, as the mysteries of his fellow scientists–and their apparitions–unfold.

However, the suspense is intermittent, and I was mostly just bored. The book contains lengthy sections that are essentially literature reviews for imaginary scientific disciplines. I had to make myself finish this book–after putting it down several times. I generally do not finish books I don’t like, but I made an exception in this case because it’s short.

The post What I’m Reading: October 2020 appeared first on Mark D. Jacobsen.

November 3, 2020

A Survival Guide for the Next Four Years

It is election day, and I am sitting in my parked car at 7pm EST while my daughter is at swim practice. Polls are just beginning to close but it is too early to guess at the outcome. Rather than compulsively check my phone every five minutes, I am reflecting on how I will approach the world when I wake up tomorrow morning.

I have strong political opinions, and often wonder whether the greatest threat to the United States is the side I disagree with or polarization itself. It’s a close tie. As a military officer, I am bound to respect lawful civilian oversight of the military, which in some ways makes things easier. Publicly raging against elected political leaders is inappropriate, and God knows we don’t need more of that anyway. The best thing I can do, as a military officer sworn to support and defend the Constitution of the United States, is to be what an Air Force colleague of mine called a “radical moderate.” That does not mean being passive or drawing moral equivalencies, but it does mean starting with the equal dignity of every American and recognizing that the greatest challenge Americans face today is finding a way to continue living together.

That challenge will be especially salient come morning.

In the best case, half of the United States will weep with joy and relief. The other half of America will weep with grief and fear, or else burn with incandescent rage. The only thing that made the past year tolerable was hope—hope that somehow an election would dispel the shadow of fear we each live under. Tonight, for half of America, that hope will vanish for the next four years.

And that is the best case. Failing that, our nation may find itself in a kind of purgatory, waiting agonizing weeks or months for a contested result. In the worst case, we may lurch into a constitutional crisis that ratchets up our country’s stakes even higher.

Regardless of which outcome results, we will all wake up in the morning. We will pour our coffee and eat our breakfast. We will drag ourselves into work, and get the kids to school or in front of a Zoom session. We will somehow survive until the weekend. Thanksgiving will be around the corner, and then Christmas and other winter holidays. The world will keep turning.

The mess we’re in will still be here. COVID19 will still be ruining our lives. Our economy will still be in shambles. We will continue to have a crisis of trust in our political institutions, exacerbated by half of America’s rage at an election that failed to deliver. Innumerable crowds of peaceful protesters will continue to fill America’s streets, but rioters and right-wing paramilitaries will collide somewhere in the country, dominate headlines, and justify our seething contempt for the radical other. Health care will still be an unholy mess for damn near everybody, and we will continue to be gridlocked on major issues like abortion, immigration policy, and climate change. African Americans will continue to stagger beneath the crushing weight of racial inequity, while police officers will continue to feel like Vietnam Vets being spat on after homecoming. Facebook will remain a toxic brew, and we will daily contemplate unfriending people we love–or once loved. None of this change will tomorrow; in fact, tomorrow will probably be worse.

The sooner we can be honest about the world we are collectively facing, the sooner we can make serious choices about how we will live in it.

If tonight proves to be a night of celebration, by all means, go celebrate. Pop the champagne, cry tears of joy, and embrace your friends. If tonight proves to be a night of grief, then shed your tears, grieve, and call in sick tomorrow if you must. Do what you need to do. But once you come through the emotional turbulence, you will face the same question that we all will: how do we live for the next four years?

Some thoughts for the day after

I wrote recently about educating my children in communities on both sides of America’s partisan divide, which led a couple readers to comment on my optimism. I chuckled, because I am rarely taken for an optimist. If my writing is encouraging, it is because I write to encourage myself. I write to restore my faith, to find an intentional way to live for my values when so much about the world seems broken.

So with that as a preface, here are some half-baked thoughts to myself—and by extension, to my readers—about how to approach the next four years.

Remember that the American people look much better at the grassroots. If you read the news or spend any time on social media, our country looks like a dumpster fire. Those feeds are populated by combing the nation for the most egregious examples of outrageous behavior on either side, then fanning the flames of outrage. There is indeed much to be upset about, which we should not minimize. But if we actually go outside and spend time with Americans of all stripes, is is amazing how sensible and decent and similar everyone is, even those who are annoying or disagreeable or outrageous. We still have so much in common. If there is hope for this country, it is not to be found in one presidential candidate or the other but in ordinary American people.

Recognize that daily life goes on. One of my most striking observations in 2020, even amidst the chaos, is the degree to which ordinary life persists. This is partly due to the resilience of ordinary people, but also due to the strength of an open democratic society that has individual liberty, free markets, and so many interlocking institutions and organizations. National politics is gravely important, but it is only a piece of the story. We live most of our lives locally—except for the hours we spend dying inside while staring at glowing rectangles. I strongly believe that the future of America is in the local. Each of us must consider that means for ourselves.

Rediscover how to be magnanimous. The winning side will have every incentive to lord its victory over the other. Republicans could interpret their victory as a mandate to steamroll over their critics, while Democrats could use a victory to unleash vengeance for four years of hurt and rage. Contempt and vengeance have not served us well to date, and they will not serve us well going forward. I expect the national arena will remain a bloodbath, but every single one of us as citizens can choose to be magnanimous in our personal relations, whether online or in person. If our favored side wins, we will be in a privileged position to work towards reconciliation; we should be gracious in victory and extend a hand to our neighbor. If we are defeated, we also must be magnanimous, accepting that this messy, convoluted, infuriating democracy has spoken in ways we did not expect. Somewhere in that is a message we need to hear.

Take comfort in the knowledge that America includes a large exhausted majority. I worry deeply about polarization, but perhaps the country is not as divided as it seems. Despite our deeply felt political rivalries, most Americans are exhausted and want to overcome our toxic divisions. Despite the cloud hanging over our country this week, I have been heartened by an outpouring of calls among friends and family on social media to work together for the sake of our democracy. We will see if that goodwill can outlast the election results, but I am hopeful that it can. Bitter rivalries cannot last forever; even in the most terrible civil wars, exhaustion and devastation eventually overshadow fear and hatred.

Encourage both parties to tame their extreme wings. Our political system rewards extreme positions, and both mainstream media and social media ensure that extremism is broadcast loud and clear to the rival camp. It is human nature to minimize or explain away extremism on our side (“a few bad apples”) while amplifying extreme behavior on a rival’s side (“they’re all rotten”). The fact is, both ends of America’s political spectrum have exhibited dangerous and deplorable behavior. Even if we feel the extremism is skewed one way or the other, both sides need to address their extreme wings; otherwise, they will continue to fuel our fear and hatred and tear us apart.

Focus on repairing damaged political institutions. The most terrifying aspect of our present era is that our political institutions may no longer be adequate for negotiating our political differences. There are a number of reasons: our institutions have been under unprecedented assault from within the country, the civic culture that upheld those institutions no longer exists, and structural forces like social media and disinformation campaigns have strained those institutions to the breaking point. The infrastructure of democracy urgently needs an upgrade in the coming years.

Continue vigorously fighting out our very real differences in appropriate political channels. Our nation faces grave challenges. Our differences are real, important, and urgent. We absolutely must fight for what we believe is right. Certain positions, ideologies, and behaviors are deplorable and will face harsh judgment from history. I expect that my grandchildren will look at certain positions from our present day the way I look at Jim Crow-era laws and attitudes. We must keep up the fight, but that is precisely why we have political institutions: to structure our political bargaining in ways that ultimately strengthen our country instead of tearing it to pieces.

Fight with the same vitality for understanding, reconciliation, and healing. Entropy is the iron law of the universe. Left to themselves, human societies will tear themselves apart in animosity, fear, and hatred. Standing against these forces takes tremendous emotional and mental energy, expended through leadership, civic engagement, and ordinary dinner table conversations. This will not happen on its own; we must deliberately work for it. Even as we battle out our contentious political issues, we must keep human dignity front and center and hold each other’s humanity. We must proactively fight to maintain personal relationships across party lines.

In Conclusion

It is almost 10:00pm Eastern right now, and I beat the polls; I am finishing this piece with no idea what tomorrow will look like.

I’m home now, sitting on the couch with my dog curled against my side. My wife and three children are huddled around another computer, trying to divine the future from the bread crumbs of data trickling in. In a few minutes, I will crack a beer and relax.

I paused from writing in order to have a substantial conversation with my children about their anxieties, about the conflicting hopes and fears of their friends in California and Alabama, about how they will handle the range of possible outcomes when they go to school tomorrow. I did my best to tell them what I wrote here.

I should be anxious, but I feel an unexpected sense of peace. Voting this morning was the most uplifting experience I have had in a long time; my wife and I stood in the cold morning sunlight, shuffling forward in a socially distanced line that wrapped all the way around the church. I had never seen so many people out voting. Cars were parked anywhere they could squeeze in. The voters were as diverse as America itself: black, white, poor, rich, urban and sophisticated, barely able to speak English, young and hurried, shuffling along bent over canes and walkers. This beautiful line held Republicans and Democrats, people whose hopes and fears were diametrically opposed and yet somehow were all out here in the bright sunlight, courteous, polite, patient.

It is a heavy night, and tomorrow will be a heavy day. The Founding Fathers never claimed democracy would be easy. If nothing else, for all our bitter divisions, we are united in one thing: we are all part of this hard, messy, contentious dance called democracy. We will not take “no” for an answer, and when the world knocks us down, we will organize and mobilize and keep fighting for what we think is right. Somehow, out of all that creative energy, the wheels of American history turn.

We are Americans, and we believe deep in our bones that we can determine our future. We will keep doing democracy. We will not stop. Not tonight, not tomorrow, not ever.

The post A Survival Guide for the Next Four Years appeared first on Mark D. Jacobsen.

October 28, 2020

Life as Commitment: Remembering Steve Chiabotti

This has been a week for thinking about legacy.

If you have followed my recent writings, you know that I have been reading, thinking, and writing extensively about the midlife passage. Far from being a crisis or a regression, this is a rich time of reflecting on one’s life, settling restless questions of identity, and finding a north star for the rest of one’s life.

I am mesmerized by men and women who find their way through this passage into a sense of joyful vocation in the second half of life. They settle into themselves, find that one thing they were meant to do with their lives, and give themselves wholeheartedly to it.

All the authors I have been savoring recently—David Whyte, Jerry Colonna, Parker Palmer, Richard Rohr, David Brooks—describe life in two acts. In the first act we are, as Brooks writes, “ambitious, strategic, and independent.” We test our wings. We set out from home, try new things, build identities for ourselves. We work tirelessly and anxiously to acquire the elements of a well-lived life, which for most of us includes a spouse or partner, a career, a home, and children. This is a restless and exploratory season in which we remain “mobile and lightly attached,” which is partly out of necessity, given both our uncertainty about our own selves and our place in a dynamic, mobile world. We finally reach a place where, successful or not in our striving, we begin to question everything that has brought us here.

Then comes the middle passage, and for the fortunate and reflective among us, an arrival into the second act. For Brooks, the essence of this second act is commitment, which might be made to a vocation, a spouse or family, a philosophy of faith, or a community—and likely all of the above. He writes:

A commitment is falling in love with something and then building a structure of behavior around it for those moments when love falters.

Commitment entails making choices and living with them. Brooks writes that people who make such commitments “are not keeping their options open. They are planted.” Paradoxically, it is the very act of foreclosing options that allows us to live deeply and wholeheartedly. If first act living is a frenzied pursuit, second act living begins with surrender–not in the sense of giving up, but in the rich sense of giving oneself over to something larger. When we meet these people, we find that their lives have a kind of serenity. They know who they are, what they stand for, and what they are meant to do in the world. Their lives become “relational, intimate, and relentless.”

A life of commitment

On Friday, I attended a memorial event for Dr. Stephen “Chef” Chiabotti, a long-time professor at the school where I serve. Steve spent thirty years in the Air Force, culminating as Commandant and Dean of the School of Advanced Air & Space Studies (SAASS), which has a mission of educating strategists for the Air Force, Space Force, and nation. He spent sixteen more years at the school as a civilian.

Steve had a varied and successful career. In his first act, he was a pilot and found a deep sense of purpose as a flight instructor and then an academic instructor. During his years on Active Duty he also developed deep expertise in wrangling bureaucracy.

The midlife passage rarely means a decisive break with the past; for most, it means a ripening of capacities, relationships, skills and interests that we acquire in the first act. That was certainly true of Steve, who leveraged his expertise in teaching and navigating bureaucracy when he transitioned into his second act: committing to SAASS.

SAASS was where Steve made his home and hearth, and the memorial event was a testimony to his legacy. By planting himself in one small school for two decades, he shaped generations of Air Force leaders—providing them with a rich education, mentorship, critical thinking skills, wisdom, and intellectual humility at critical moments of their careers. More than 60 people joined via Zoom from across the world, a significant number of whom were general officers. Steve’s mastery of bureaucracy paid dividends in many of their lives; attendees shared story after story of Steve’s intervention in their careers to protect them and open up opportunities at decisive moments. Steve’s life was a powerful example of how the strategic skills one develops in the first act of life can be harnessed to serve second act purposes.

I personally was a beneficiary of Steve’s generosity and talent; after an eight-month gridlock in which multiple general officers could not break through an administrative logjam to get me into the assignment we knew was right, Steve cooked up a solution and made it happen. All the work I did at DIU flowed from that assistance.

I barely knew Steve outside of work, but it seems clear through others’ stories that he made equally strong commitments to his family, friends, and community.

Montgomery, Alabama is, to be candid, not the first place where most Air Force officers would choose to commit themselves. Steve did. By planting himself at SAASS, Steve made Montgomery his home, and he made his home a place of community.

His cooking was legendary, and cooking was an excuse to bring people together. Shaylyn Romney Garrett writes, “There’s a unique sort of bonding that is initiated when we provide sustenance to others.” She describes sharing meals as a universal human experience that joins people even across languages and cultures—an experience we have largely lost in our individualized Western culture. Steve pushed back on this relentless individualism, providing meals for innumerable SAASS events and frequently opening his home for good food and fellowship. I enjoyed his hospitality at his home more than once.

Steve was taken far too soon, just a few years into retirement at 69. I am sure I am not the only one who felt compelled to consider the passage of time, the uncertainty of our span on this earth, and the legacy we each will leave.

A well-lived life is a life of commitments, and Steve lived well. By committing himself to SAASS, to his family and friends, and to Montgomery, Steve left a powerful legacy—not merely a career, not merely a list of achievements, but generations of men and women who are better leaders and human beings for having known him.

The post Life as Commitment: Remembering Steve Chiabotti appeared first on Mark D. Jacobsen.

October 22, 2020

Raising Citizens in The Two Americas

My three children have received quite the education over the past year—and I don’t just mean school.

Like children across the world in the COVID19 era, they have received a practical education in adaptability, resilience, disaster management, self-directed play and learning, and managing their own emotions. During lockdown my ten year-old daughter wrote a poem and story that showed an astonishing depth of insight into the emotional roller coaster she was riding. Cloaked as it was in fiction, she herself did not fully recognize the powerful cry of her unconscious.

Some of their greatest learning, however, has been about political polarization. They spent the past six years in a public school in Silicon Valley, which is about as politically liberal as America gets. Their friends came from a wide variety of ethnic backgrounds, spoke numerous languages, and held passionate and deeply personal views about immigration. My children studied global warming in school and performed school plays about environmental stewardship. Instead of Columbus Day, they celebrated Indigenous Peoples’ Day. If anyone in their school or neighborhood voted for Donald Trump, it was a closely-guarded secret. Their school valued creativity, experiential learning, and the individual expression of each child.

In July we moved to Montgomery, Alabama, which is as politically conservative as Silicon Valley is liberal. Our children resumed their education in a small private, Christian school, which values classical education, tight haircuts, and grammar drills. Now it is the Biden supporters who are in the closet, while Trump-Pence signs adorn many lawns—usually alongside JESUS 2020 signs. On Columbus Day, my children brought home a book hailing Christopher Columbus as a hero. Their school celebrates patriotism, pledges allegiance to the flag, and advocates for individual responsibility and strong families.

Before our move, my wife and I wondered how such an abrupt transition would go, particularly during this time of toxic political polarization. We endlessly discussed how to educate our children, in what kind of school.

A few months into this new adventure, however, I have to say that I am incredibly grateful that my children are growing up with firsthand experience in both halves of the United States. At a time when our country has so thoroughly sorted itself into opposing camps, this is a rare and valuable opportunity that many Americans will never know. Our “foreign immersion” in different parts of our own country has been every bit as exotic as the two years we spent living in the Middle East.

The first and most striking reality my children encountered is that kind, loving, generous, and good people can be found anywhere, even when they hold radically different political perspectives from each other. After six years in Silicon Valley, my children had internalized a thoroughly dehumanized stereotype of “the other”; they only set foot in their new school with trepidation. They were delighted to discover a cadre of teachers who—just like their teachers in Silicon Valley—were warm, generous people who loved them, cared about their academic success, and more importantly wanted them to grow up to be thoughtful, compassionate people and good citizens. Now the “othering” process is playing out in reverse; my children frequently return home shocked at the latest dehumanizing stereotypes they hear about liberals and Democrats.

My delight in having a foot in two worlds does not mean that I draw moral equivalencies. My wife and I still have strong views on many issues, and we are utterly baffled and saddened by some viewpoints we encounter. Like most Americans, we are exhausted and demoralized by the erosion of our democracy, gridlocked political institutions, political toxicity, the collapse of civil discourse, and the celebration of corrosive extremism. We believe that democracy demands not the papering over of differences, but vigorous engagement with them. We believe that some political viewpoints are worth tirelessly fighting for, and others are worth tirelessly fighting against.

Yet we also believe that the messy, hard, contentious work of democracy must play out with civility and with a basic respect for individual human beings. Hard though it might be, we have to keep our common humanity in sight. Much of the outrage on both sides springs from a deep sense of fear and woundedness, as we all feel that the “other” is on a ruthless crusade to deny our basic humanity.

My children are carrying a lot right now. They feel personally invested in many political issues. My twelve year-old son, a passionate environmentalist, is baffled and almost hurt by the widespread skepticism of global warming here. My daughter comes home several days a week, processing her teacher’s prayers for political outcomes that would mortify her teachers at her previous school. I worry, sometimes, that they are carrying too much. So much easier, I think, if they lived ensconced in a single community of like-minded family, friends, and neighbors who affirmed each other’s beliefs in every conversation.

Easier, undoubtedly. But our family has never chosen to live easy.

My children are learning how to be citizens, with all the uncomfortable complexity that demands. They are learning about the great debates of our time, but they are learning about these debates from within communities of real, living, breathing people. Unlike the raucous invective that passes for discourse on social media, they are participating in human discussions. They can never take the easy way out–despising the other–because the other is a friend, teacher, or relative, in one world or the other.

Our dinner table has become a place of rich conversation. This week we have had sophisticated conversations about Amy Coney Barrett, about the fierce battles for the Supreme Court, about Republican and Democratic perspectives and tactics, about election year nomination blocking and court stacking. We have talked about abortion, about the meanings of “pro-life” to different political and religious communities, about the relative prioritization of issues, about single-issue voting and more comprehensive platforms. In the weeks before that our children watched Presidential and Vice Presidential debates, and in the days that followed we talked about different narratives they heard assessing the performance of each candidate. Racial equity issues are front and center here, and we discuss them almost every day.

I have no idea if we are doing it right. Perhaps our children, under the cognitive and emotional strain of so much dissonance, will later be easy prey for fundamentalists or ideologues, who promise easy answers. Maybe, exhausted, they will simply turn a blind eye to contentious political issues and withdraw into private, safe worlds.

Then again, maybe, just maybe, our children will learn to be American citizens.

Maybe they will grow up comfortable with complexity and uncertainty. Maybe they will learn to embrace the creative tension of holding another person’s humanity, and hearing others out without feeling personally threatened. Maybe they will learn to listen to the best possible arguments on an issue from multiple perspectives, then still have the courage and strength to stand by what they believe to be right. Maybe they can learn to do so with civility and respect. Maybe they can still be good friends and neighbors, even amidst profound disagreements about consequential, high-stakes issues.

I have to believe that about my children, because I have to believe it about the rest of us. Each day, as I navigate these thorny questions about how to educate my children, I am forced to look in a mirror. I must be alert to hypocrisy, ensure I am living out what I hope for my children. Striving to be a better parent is, I hope, making me a better citizen.

All of us in the United States are under tremendous strain. So many of us feel powerless, in the face of structural forces that seem to be tearing our country apart. But a democracy ultimately depends on its citizens, and the responsibility to be good citizens starts within each one of us.

As I am learning from my children, becoming a good citizen is an ongoing process that we can and must live out each day.

P.S. For my wife Wendy Luce Jacobsen’s rich perspective on finding hope in these times, you can read her writing at Healing Division.

The post Raising Citizens in The Two Americas appeared first on Mark D. Jacobsen.

October 18, 2020

Personal Branding vs. Our Whole Selves

Like most writers, I struggle with powerful internal demons that together constitute what Steven Pressfield calls Resistance—a malevolent, almost tangible force that resists our most noble and heroic efforts to rise to our fullest potential. Resistance paralyzes us with senses of fear and inability. Every good piece I have ever written only emerged after a difficult inner battle.

One source of struggle is the overwhelming pressure to brand oneself. One definition of personal branding reads:

The conscious and intentional effort to create and influence public perception of an individual by positioning them as an authority in their industry, elevating their credibility, and differentiating themselves from the competition, to ultimately advance their career, increase their circle of influence, and have a larger impact.

In other words, branding is how we communicate and present our value to the world. One of the first questions we encounter at cocktail parties is, “What do you do?” Each of us is obligated to have a ready answer. We usually encounter this concept in a professional context, but the world constantly asks to name our identity in a wide variety of other contexts.

I have always struggled to name my identity, and I grow less certain with each passing year. I have been extremely fortunate to have had a rich variety of experiences in my life. Officially, I am an Air Force officer and cargo pilot who no longer flies. I know Arabic and am a Middle East Foreign Area Officer, but have never worked a FAO job. I am an entrepreneur who founded two drone-related startups. I am a Political Scientist currently working as a professor. I am also, less officially, a writer of science fiction, fantasy, memoir, defense innovation pieces, and blog posts loosely aimed at helping leaders find a place of wholeheartedness from which to lead. I enjoy this rich complexity but also feel spread thin.

The pressure to name my identity is a constant source of anxiety. As I put together this website, questions of identity felt increasingly urgent. Do I use my own name as a web domain, or pick a catchy topic-specific name that is likely to drive more traffic? Do I create separate websites for each aspect of my life, or somehow integrate them into a single website? How do I write about diverse interests without alienating the majority of readers drawn by just one topic? Do I throw everyone on one mailing list or maintain multiple topical mailing lists? How do I present myself on a CV?

Lost in all this anxious thrash is the joyful magic of creation. Following my heart, writing what sings to me on any given day, never feels like enough. It must fit a strategy, fit a brand, avoid confusing my readers by straying too far from their expectations. Why the hell is a military officer quoting poetry and writing about inner journeys? And if he wants to write about inner journeys, why he is suddenly writing about social science or coding? I sit before the blank page, wheels spinning, stressing about identity management and market position rather than doing the thing I truly love: creating.

I share all this not to navel-gaze, but because I suspect I am not the only person who feels this way. Not everyone is a writer. Not everyone has the diversity of professional identities I have cycled through. However, each of us is a complex and multi-dimensional person with wide-ranging interests and a sense of self that bristles at being put in a box.

The pressure to name our identity

Why do we feel so much pressure to name our identities?

One class of incentives is economic. Strong economies are built on specialization and exchange, and we live in a time when the sheer range of possible specializations boggles the mind. Our distant ancestors might have specialized in hunting mammoths or picking fruit, but today a front-end web developer frets over which technology stack to specialize in. Most academics build successful careers by specializing in tiny slivers of human knowledge.

Freelancers might not be constrained by organizations, but they arguably face an even tougher problem: economic incentives to brand their own personal identity. It is not enough in today’s world to be a wise, emotionally intelligent, multi-dimensional thinker with a range of skills and experiences. The winners in the modern economy can state the value proposition of their professional lives in a sentence. Specialization sells. A blog entirely devoted to YouTube search engine optimization will probably outcompete a personal blog maintained by a polymath with diverse interests.

Social incentives also drive us to name identities. The human mind will do almost anything to avoid complexity, which is cognitively demanding and emotionally draining. Identities bundle complexity into digestible nuggets. They become shorthands for entire worldviews, which allows us to bin people into a comprehensible framework with almost no contextual knowledge. Social identities become in-group and out-group markers that allow rapid sorting of communities and relations.

Perhaps the deepest incentives to name identities lie within. We desperately want to know who we are. Most of us don’t. In our formative years we live out identities handed down from authority figures or culture. As we grow older, we experiment with alternative identities and begin to learn who we really are. Around midlife, we shed worn-out identities and grow into new ones. The ambiguity of these seasons can be disorienting and even painful. We are uncertain how to live in the world when we cannot even live comfortably within our own skin. Identity markers–even someone else’s identity markers–anchor us and promise to settle our uncertainty.

Crises of identity

Although these pressures to name our identities are inevitable and perhaps even necessary, they can lead to a number of stresses that challenge our full humanity.

First, the human soul yearns for spaciousness and freedom. Each of us is a multidimensional being, far too complex to pin down with mere labels. Identities reduce us, constrain us, hammer us into containers too small for the welling abundance within. Each choice we make about presentation seems to foreclose other opportunities. Establishing our presence in the world becomes a zero-sum game, in which we constantly worry over identity decisions and the opportunity cost of paths not taken.

Second, naming identities works against the magic of synthesis. Each of us wears multiple identities, and these identities can interact in challenging and sometimes profound ways. In the corporate world, Americans long drew a boundary between professional and personal identities. The collapse of that boundary has opened up a creative, engaging, and important space in which we can discuss emotional intelligence, empathy, wholeheartedness, and meaning in the context of work. Many scientific breakthroughs occur when scholars make lonely, uncertain expeditions into other disciplines to discover connections. One reason I love fiction is that it encourages an expansive way of understanding the world, drawing liberally from the human experience, history, knowledge, and imagination.

The pressure to name a narrow identity works against this ongoing process of creative synthesis. It pressures us into conformity—into cultural norms, genre tropes, the conventions of particular scientific disciplines, established ways of living and being. Living across identities requires intentionality, energy, and courage. It often means being misunderstood and alienated. Scientists, artists, and other creatives who work across identities often struggle to find the acceptance that they so earnestly seek.

Third, identities are malleable and highly uncertain to change. We marry and divorce. We undergo religious conversions and transformations. We experience job changes, sometimes radical ones. Old interests fade and new interests arise. A well-lived life involves a constant process of growth. Fixed identities curtail that freedom, creating drag on our ability to grow and change.

Identity transformations can thus become lonely and dangerous experiences. Religious transformations, although sometimes sorely needed, can feel like relational suicide. Scholars who want to change disciplines do so at the risk of their careers. Authors trying to cross genre lines sometimes write under pen names, deliberately fragmenting their identities in order to sell their work.

Fourth, shorthand identity markers are simplifications at best and outright lies at the worst. Consider how much baggage is packaged in a label like Democrat or Republican or Christian or Atheist, a slogan like “Black Lives Matter” or “science is real”, a genre like Science Fiction or Romance. When we tag ourselves—or others—with such a shorthand, we invoke a long and encumbered history, which might only loosely represent a unique individual. To the degree that our private beliefs differ from that prefabricated identity, we can feel great personal stress, pressuring us to drive our private beliefs into conformity, suppress them, or shed the identity entirely.

Holding identity in tension

Although I do not have easy answers for managing complex identities, here are a few principles. They all involve a creative tension between personal wholeness and the practical needs to mark identity.

Become conscious of the forces constraining identity. Understanding these forces is half the battle. It allows us to engage intentionally and deliberately with identity management, rather than being swept along by unconscious forces that constrain us.

Recognize there is no perfect answer to identity management. There are only tradeoffs. One website or three? Pen names or not? Different CVs for different communities? Religious label or not? All we can do is bring our best judgment to bear, make decisions, and move ahead. Stalling rarely helps.

Remember that you are more than your presentation to the world. Wholeheartedness demands fluidity, integration, expansiveness. Even if the world requires us to brand ourselves in particular ways, we must retain that wholehearted sense of integration within. We must not confuse our tactical presentation with the full breadth of who we are as individuals. We need spaces in our lives where we can unfurl our whole selves across the canvas, whether that is in our relationships, journals, arts, or somewhere else.

Know that resisting identity pinning requires a countercultural commitment. Not everyone will make this choice, but those who do should be clear-eyed about the implications. It will likely mean difficulties with all the things that branding is designed to solve, such as sales, quick connections with existing communities, or even understanding. It will mean a higher expenditure of energy. On the positive side, it will likely bring a sense of constructive chaos, of serendipitous collisions, of humming energy from unexpected directions. Every once in a while, it will bring a convention-shattering breakthrough.

Create space for others to live beyond their identities. Once we understand these dynamics within ourselves, it helps us create space for other people. For example, I felt severely constrained by the norms of my academic discipline when I was a PhD student. Now that I am a professor, I try to be more expansive in what I consider a valid research project. I am honest with my students about the opportunities and pitfalls of going in certain directions, but I want to err on the side of letting them follow their deepest instincts and pursue their deepest passions.

Remember that branding is malleable. These decisions seem so consequential in the moment. Yes, altering these decisions later can require time and energy, but people—like companies—rebrand all the time. Nothing is forever. You will always be yourself, and you can always find ways to alter how you present yourself to the world.

Look for points of intersection between identities. Magic happens when brave individuals dare to cross stovepiped identities. I have previously written about Jerry Colonna and David Whyte, who have carved out a unique genre to guide corporate executives on their inner journeys. I love eclectic novels like Helen DeWitt’s The Last Samurai, which draws on the author’s far-ranging interests and defies any kind of genre norms. I love the scientific community around complexity theory, built by renegade biologists, physicists, economists, and other scholars who saw something profoundly wrong with the prevailing methodologies and theories in their disciplines. Each of us has our own unique intersection of identities, which creates rich opportunities to give something new to the world.

Keep showing up. This last point is a personal reminder to myself. Anxiety about identity management can become an excuse to stall, to hide, to wait until we have everything figured out. In these moments, we need to continue participating with the world, learning, sharing, and giving. We will figure it out, and even if we don’t, it will be a wonderful ride.

Our rich, multi-dimensional lives will always stand in tension with the demands of society and the market to brand ourselves with specific identities. Managing these identities can be difficult and even painful, but the creative tension can also be a source of creativity and generosity to the world.

Photo by Mohamed Nohassi on Unsplash

The post Personal Branding vs. Our Whole Selves appeared first on Mark D. Jacobsen.

October 2, 2020

What I’m Reading: September 2020

All of us enter seasons, from time to time, when we feel we have lost our way. I have been in one of those seasons lately. My involvement in my last startup came to a turbulent, unexpected, and deeply disorienting end a few months ago. Add in a cross-country move, the alienation imposed by COVID19, and the unraveling of American democracy, and the result is an existential sense of dislocation.

Fortunately, my personal journey is hardly unique. This midlife disorientation is an almost universal part of the human experience, and some wise and good writers have done us the great service of acting as guides. Most of my reading list this month reflects time I have spent sitting at their feet.

Crossing the Unknown Sea, David Whyte

[image error] [image error]

I first encountered David Whyte in Jerry Colonna’s book Reboot, which I read last month. The notion of a poet who wrote about work caught my attention. I am so glad it did; this is one of the most beautiful and powerful books I have read in a long time. The prose is consistently gorgeous. This is one of those rare books I will return to again and again, just to savor the majestic beauty of individual sentences.

This was exactly the right book for me at this time in my life. Whyte writes of his own sense of dislocation, which led him to follow an inner call away from organizational leadership to pursue his dream of becoming a poet.

Whyte cuts right to the heart of the midlife passage, with all its profound questions about identity and purpose. For example, he writes,

To have even the least notion of what we want to do in life is an enormous step in and of itself, and it is silver, gold, the moon, and the stars to those who struggle for the merest glimmer of what they want or what they are suited to.

He also captures our deepest yearnings for a life half-glimpsed beyond the horizon:

Some have experienced fulfillment for only a few brief hours early on in their work lives and then measured everything, secretly, against it since.

I underlined dozens of such passages as I went, each of which sang to me.

Whyte recogizes that the pursuits of good work and good lives are inseparable. He emphasizes the nobility and glory in good work, validating our yearning for it. Yet he also recognizes the immensity of the challenge to find good work; it is a journey and a pilgrimage, not a destination, and “there is almost no life a human being can construct for themselves where they are not wrestling with something difficult.”

Perhaps the best we can do is learn to dwell in the deepest parts of ourselves, to listen to the quiet voice within that pleads to be heard but is so often drowned out by our ceaseless activity. To be truly alive, we must learn to live at what he calls our cliff edge, that dangerous but beckoning horizon we often fear to approach.

Whyte ultimately views the pursuit of good work as a living conversation between ourselves and the world. It is always a negotiation, always a mutual search and accomodation. You cannot find a better book to guide you into that conversation.

Essentials, David Whyte

[image error] [image error]

I was so enraptured by the first chapters of Crossing the Unknown Sea that I immediately ordered several more of Whyte’s books. The first was Essentials, a slim, pocket-sized volume of his best poems. The economy of his poetry stands in contrast to his rich prose, but it is perhaps even more powerful—a concentrated dose of all his heart and insight. Nearly every poem hit me with tremendous force.

Many of these poems articulate every step of the midlife passage, every hidden thought I have struggled to find my own words for. “Sweet Darkness” beautifully captures both the heartbreak and the hope of this passage. I hesitate to do violence to the poem by only quoting part of it, but you can read the entire thing here:

Time to go into the dark

where the night has eyes

to recognize its own.There you can be sure

you are not beyond love.The dark will be your home

tonight.The night will give you a horizon

further than you can see.

My throat also caught at Mameen, which crystallized my experiences of failure into something I can treasure:

Recall the way you are all possibilities

you can see and how you live best

as an appreciator of horizons

whether you reach them or not.Admit that once you have got up

from your chair and opened the door,

once you have walked out into the clear air

toward that edge and taken the path up high

beyond the ordinary you have become

the privileged and the pilgrim,

the one who will tell the story

and the one, coming back from the mountain

who helped to make it.

So many other poems touch on other related aspects of this journey through lostness and renewal. Equally powerful are the handful of love poems, which evoked a bright and deep appreciation for my wife as I read them. There is little more I can say, as the poems need to speak for themselves.

If I was stranded on a deserted island, Essentials is now among the books I would want with me. I have begun memorizing my favorite poems so I can always have them at hand.

P.S. Whyte is also a wonderful speaker. I enjoyed this webinar, which speaks to the pain and alienation of our COVID19 era.

Given, Wendell Berry

[image error] [image error]

I do not read poetry very often, but I picked up this volume years ago after a friend recommended I try Berry. I rediscovered it on my bookshelf one evening recently when I was feeling restless. Although it did not hit me with the force of Whyte’s poems, I did enjoy it.

In addition to being a poet, novelist, and essayist, Berry is a farmer and environmental activist. His writing has an earthy, simple goodness to it, evoking my memories of visiting my grandparents as a child on their small family farm. These are poems about birds and flowers, hills and streams, the changing of the seasons. They are intimately tied not just to landscape in general, but to specific places. Berry celebrated the local, which is perhaps countercultural in our transient, mobile world; as his Wikipedia entry puts it, “His writing is grounded in the notion that one’s work ought to be rooted in and responsive to one’s place.”

I read the book over several evenings, and found the poems a refreshing alternative to the stresses and pressures of our crazy times. They are a call to not forget who we are:

What I fear most is despair

for the world and us: forever less

of beauty, silence, open air,

gratitude, unbidden happiness,

affection, unegotistical desire.

More than an escape, these poems are a challenge to see and experience daily life at a much deeper level. Nearly every poem is a meditation on everday miracles that most of us, in our frantic desperation, would never take the time to see.

Startup Life: Surviving and Thriving in a Relationship with an Entrepreneur, Brad Feld

[image error] [image error]

I discovered entrepreneur, venture capitalist, and writer Brad Feld while researching mental health among entrepreneurs—a subject near and dear to my heart, after my scorching experiences over the past few years. Brad has built a remarkable career in the Boulder, Colorado startup ecosystem, but he is especially remarkable for working to dismantle the taboo around discussing mental health in the startup world. He has written numerous articles, appeared in a TechStars mental health series, and spoken candidly in venues like the Tim Ferriss podcast.

Startup Life, coauthored with his wife Amy Batchelor, is a relationship manual for entrepreneurs and their significant others. I had no idea such a book existed, and think it could be helpful for many founders. Much of the book mirrors general relationship and marriage advice available in other books, but it shows a unique sensitivity to the pressures of startup life; there are limits to how much founders can slow down in this arena and still survive, which in turn imposes unique strains on relationships.

I have been married long enough, and read enough relationship books, that I can’t say I gleaned too much new information. Nonetheless, I enjoyed the read. Brad and Amy are what make the book strong; they have such authentic voices, and seem comfortable with themselves and each other, and their humble example gives them unique credibility. Probably the most interesting aspects of the book to me were practical strategies and practices they have developed to keep their own marriage strong.

Startup Communities: Building an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem in Your City, Brad Feld

[image error] [image error]

Very different from Startup Life, Startup Communities is about building an innovation ecosystem in a particular locale. The style is again casual. Brad seems comfortable in his own skin; coming straight from my reading of Startup Life, I was impressed with his ability to shift between varied subjects to weigh in with informed perspective.

I was evaluating this book for possibly inclusion in the innovation course I teach. It caught my eye because so many government innovators right now want to create their own innovation ecosystems. I am usually skeptical of these efforts; government efforts to build innovation ecosystems often consist of creating a dazzling new building, then passively waiting for innovation to happen. I once saw Marc Andreessen give a talk in which he laid out the ingredients of an innovation hub like Silicon Valley: abundant capital, a critical mass of talent, a risk-taking culture, a nexus of companies and universities, and so forth. He said that when he describes these elements to government ecosystem-builders, they usually look at him blankly afterwards and say, “Okay, let’s say we can’t have any of those things… THEN how do we build an innovation ecosystem?” That story still makes me laugh because it rings so true.

This book reminds me of that talk. Brad focuses the book on his own home innovation hub in Boulder, Colorado. He pays special attention to the different kinds of stakeholders and their roles. He unapologetically believes that entrepreneurs need to be the driving force for innovation, and that everyone else—like government, investors, and universities—can only ever be in supporting roles, although these roles are important.

Some might find the focus on Boulder too narrow, but Brad’s goal is to use this specific example to show how innovation ecosystems might grow elsewhere. In his introduction he says:

I have a deeply held belief that you can create a long-term, vibrant, sustainable startup community in any city in the world, but it’s hard and takes the right kind of philosophy, approach, leadership, and dedication over a long period of time.

If that whets your appetite, the book is worth a read.

Faith: Trusting Your Own Deepest Experience, Sharon Salzburg

[image error] [image error]

This is another book I discovered through Jerry Colonna. In 2002 he was, in his own words, at the lowest point in his life. He was “at a point where, as St. Augustine wrote, my soul was a burden, tired of the man who carried it.” Three books helped him reboot his life: Let our Life Speak by Parker Palmer (which I reviewed in July), When Things Fall Apart by Pema Chodron, and Faith by Sharon Salzberg.

Salzberg aims to rescue the concept of faith from the necessity of believing specific religious claims. She writes, “whether faith is connected to a deity or not, its essence lies in trusting ourselves to discover the deepest truths on which we can rely.” The book is part memoir, part spiritual reflection, and part introduction to Buddhism, as Salzberg recounts her own story; a story “of knowing, even in the midst of great suffering, that we can still belong to life, that we’re not cast out and alone.”

This is a fine book, and well-crafted, although it did not resonate with me in the way that other books have. Perhaps I went in with too high of expectations, or perhaps I was spoiled by books like Whyte’s that spoke so precisely to my current journey. Most of the territory felt well-trodden. If I took one thing away from the book, it was a sense of validation about my own feelings of disconnection and encouragement to lean into the pain–not to deny it or run from it. One passage reads:

All of us go through times in our lives when we feel as if we are lost in a wilderness, caught in a violent storm. Exposed and vulnerable, we look for something or someone to help us through the upheaval. We look for a place of safety that won’t break apart no matter what we are experiencing. As many of us have discovered, the refuge we may have sought–in relationships, in ideals, in points of view–ultimately lets us down. We begin to wonder, Is there any refuge that is real and enduring?

That is exactly it. The pain of that question leads some people to “walk away”, in Salzburg’s words, which breeds cynicism. Salzburg sees cyncism as “a self-protective mechanism. A cynical stance allows us to feel smart and unthreatened without really being involved.”

A persistent willingness to engage those deep doubts is how we surpass cynicism to find new life. This is hardly easy. At one point in the book, Salzburg blurts out to a teacher, “Isn’t there an easier way?” That is the universal question, and the answer is invariably no.

The Bureaucratic Entrepreneur: How to be Effective in Any Unruly Organization, Richard Haass

[image error] [image error]

A reader of my blog recommended this book to me. I was amazed that I had never heard of it before. The book is about getting things done in government, and it was written by a man who can speak from experience; Haass was a special assistant to President George Bush Sr. and a senior director on the National Security Council.

I’ll admit that reading a book about government bureaucracy felt a bit dreary, after reading the invigorating, soulful books by Whyte and Salzberg. However, if we want to have an impact in this world, we cannot isolate ourselves from the messy, hard, and frustrating work of engaging with people, organizations, and the complex problems we all face together. Our soul work should lead us to a place where we are equipped to re-enter the world. This might be the best book you will find on how to meaningfully do that in government.

Haass begins with an honest recognition of how hard it is to work inside government. He notes that bureaucracy was once “championed by advocates of good government. It was a welcome inovation, one designed to add professional standards and checks and balances to institutions and processes all too commonly characterized by corruption, spoils, and patronage.”

Now, he writes, bureaucracy is viewed as part of the problem they were meant to solve:

No democracy can thrive for long amid the perceived failure of its governing institutions, for such failure breeds cyncism, alienation, and in, the end, desperation.”

He wrote those words in 1993; I can only imagine what he would think of government in 2020.

Rather than despair, Hass says that all of us in government have a responsibility to help close this gap. He develops the metaphor of a compass to guide policy entrepreneurs in their efforts to be more effective in getting things “done”—which means not just approved but implemented.

At the center of the compass is you. You must know your values, your strengths, your weaknesses, and your personal agenda. Effectively managing yourself is the foundation of your public service, competence, and ability to influence. Doing anything in government requires working together with diverse stakeholders, so the rest of the compass points to others; north is those for whom you work, south is those who work for you, east are those with whom you work, and west are those external stakeholders with whom you should work. Each chapter of the book is dedicated to a different compass point, and packed with strategies for effectively working in this human territory. The book is enriched by dozens of interviews with other policymakers.

To the best of my knowledge, this is the only book of its kind; Haass wrote it precisely because such a book did not already exist. Every part of the book rang true to my experience leading innovation at DIU, which often entailed messy entanglements in policy. The book is practical and wise, honest about the difficulties of government while still being optimistic. My only critique is that the book is beginning to show its age; the first edition was published in 1993, and the second in 1999. Haass’s examples will be old history for a rising generation, and it would be helpful to see Haass weigh in on the rapidly worsening dysfunction in government today. Nonetheless, I’d still recommend the book for anyone working in government policy.

The post What I’m Reading: September 2020 appeared first on Mark D. Jacobsen.

September 22, 2020

When Innovation Bites You in the Ass

Last year I gave a talk about innovation to an Air Force audience. I have done this many times before and knew the minefield I was stepping into. The Department of Defense has achieved the stunning feat of turning Innovation! into a hated buzzword, so every talk starts with a chasm between my audience and me. They sit with folded arms, peering suspiciously at me, almost daring me to try to impress them with technical jargon and Silicon Valley references and heroic admonitions to go ideate and think differently and disrupt, so they can quickly write me off as another expert practitioner of innovation theater.

Instead, I usually leap onto their side of the chasm. I ask them what the word “innovation” evokes, and we immediately begin a vibrant conversation about hypocrisy, hollowness, and the desire to vomit. Then I tell my own stories about trying to innovate within government, dwelling perhaps a little too long on the anger and hurt and frustration. I narrate my victories and defeats and show them my scars. It is my unique style; candid, curmudgeonly, too grim for the tastes of some of my colleagues.

Yet something magical usually happens; as we dive into the gritty reality of how hard it is to actually innovate within government, my audience comes alive. We finally name the frustrations and roadblocks each of them faces. And out of that conversation, at least some of the audience walks away inspired. Deep beneath all the accreted layers, we find that kernel of innovation that is still worth fighting for, that keeps us all going even when it is hard.

This time, though, I met my match. At the end of my talk one officer still had his arms folded over his chest, one boot propped up on a knee.

“I have a question,” he said, with a decisive tone that said this was not a question but a telling. His voice was that of a man who had stared into the innovation abyss. He began to tell his story.

The Maintenance Officer’s Tale

He was a maintenance officer who had once been stationed at an Air Force base in the Pacific. Nothing is so corrosive to airplanes as saltwater, and approaches and landings over the ocean subject airplanes to sea spray. For this reason, some bases in the Pacific regularly rinse airplanes after landing. As you might imagine, washing a four-engine jet aircraft is no small undertaking.

When this officer first arrived at the base, washing planes was an intensively manual process. Multiple maintenance troops had to operate the equipment and spray down the planes. An innovation naturally suggested itself. The group worked hard, fighting many battles, to have an automated aircraft washing system installed. It worked marvelously. A plane could land, taxi to a washing station, and be quickly rinsed back to health—all with little burden on the maintenance troops.

This new innovation worked so well, in fact, that higher headquarters decided the base no longer needed so many maintenance troops. It whittled down the force until those who were left found their time just as encumbered as before.

Then, because the Air Force had not invested appropriately in maintenance for the aircraft washing system, it broke. Funds were not available to repair it. Now the slashed, undermanned maintenance unit found itself working overtime, manually washing airplanes again.

A Perfect Anecdote

The officer had finished his story. A hush fell on the room.

The gauntlet had been thrown down.

“What,” he asked me, “do you make of that?””

I love and hate this anecdote, the way I might a particularly unsettling horror story. It is pitch-perfect, Kafkaesque, capturing so much in a few brushstrokes. Like a timeless myth, it contains a kernel of truth that I see replayed in so many other stories.

I thought of this story when a friend, who had just wrapped up his tour as a Battalion S3 (in charge of Operations and Training), described a failed effort to automate inventory management with RFID tags. The technology sucked, and he found it much easier to revert to making soldiers burrow through the warehouse with a clipboard, pencil, and inventory hardcopies.

I recall all the software tools that my colleagues and I built to automate manual processes in our flying Squadrons—which broke as soon as we left.

The implicit moral in this cautionary tale is that innovating is like opening Pandora’s box. In our efforts to improve things, we unleash terrible second-order effects that can undermine our best intentions. Don’t tamper with something that works, however imperfect. Automation is never to be trusted. Innovators are dangerous charlatans, and it will fall on the old guard to clean up their messes.

A Few Thoughts

The officer’s question was fair. What do we make of this?

I have thought long and hard on this question, and I can’t do much better than the tentative answer I suggested that day.

First, the anecdote does contain a valuable lesson. We need to pay attention. Change is hard, and many nascent innovations fail to live up to their promise or even cause damage. Good leaders must orchestrate the change process to mitigate risks even as they experiment with new ways forward.

With that said, we must not stop innovating.

Martin Luther King Jr., paraphrasing Theodore Parker, famously said, “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.” It was a call to stick with a fight for the long term, through all the ups and downs. The moral universe has its own peculiar logic; no matter how far human efforts might stray, they always steer back to moral right.

At the risk of trivializing the powerful sentiment in that quote, we might generalize it to any kind of change-making endeavor: The arc of innovation is long, but it bends towards improvement. Bad ideas go extinct, or else evolve into good ones. No organization, with its hundreds or thousands of independent, creative, aspiring members, will tolerate badness for long; it will always strive for the best solution according to some internal metric. And yes, organizations sometimes chase bad metrics, but that condition cannot last either. In the long-term, organizations must evolve towards The Right Answer or die.

I told this officer that if he stepped back to look at the problem he faced, automating a repetitive, labor-intensive process like washing airplanes was unquestionably the Right Answer. That is precisely the kind of task that machines exist for, and we have seen in other parts of society the tremendous benefits of freeing up human capital to focus on more interesting, demanding, value-adding tasks.

It was unfortunate that this officer and his colleagues found themselves working overtime, rinsing planes after their machine broke… just as it is unfortunate that my Army friend had such a negative experience with automating inventory management, and that hundreds of tangled PowerPoint and Excel-macro workflows across the DoD break every time their creators move to new jobs.

However, it was also unfortunate that early automobiles were notoriously unreliable, leaving their owners fuming as passerbys mocked them from horseback. In retrospect, that didn’t stop the long progression toward a world of safe, reliable vehicular transportation.

We have frequent glimpses of where the future is headed, because segments of human society are already several steps ahead of the rest of us. As Science Fiction author William Gibson said, “The future is already here–it’s just not evenly distributed.” We should not chase every fashionable new trend, but we should also pay attention when new trends show enduring value and catch on at scale.

Driving a positive innovation through might take years, decades, or generations. You might absorb pain now so that your successors might benefit. You will take your licks. However, if you are on the path towards the Right Answer, your efforts are not in vain. Rather, you are discovering firsthand that you are part of a story much larger than yourself.

The post When Innovation Bites You in the Ass appeared first on Mark D. Jacobsen.

September 19, 2020

Harnessing Your Discontent

Below is a guest post I wrote for my friend LTC Joe Byerly’s blog, From The Green Notebook. Joe and I got to know each other during the earliest days of the Defense Entrepreneur’s Forum, and since 2013 his blog has emerged as one of the best sources for mentorship in the profession of arms. I am honored to contribute something. Although the piece is specifically aimed at military service, the themes are relevant to anyone.

When I arrived at my first C-17A unit, I was chomping at the bit. Finally, after years of education and training, I was ready to join the fight. The September 11th attacks had occurred during my senior year at USAFA, and I had felt like I was missing out by not serving in Afghanistan and Iraq.

C-17 life could indeed be fantastic. The jet was amazing. I loved my coworkers, who were intelligent, mission-focused, dependable, and a lot of fun. My first C-17 trip was exhilarating: drinking German beer one day, and the next slipping on body armor, a helmet, and night vision goggles before descending into Iraq.

Yet I was also in for a rude awakening. The operations tempo came as a brutal onslaught. My office duties seemed designed purely to satisfy “the system’s” insatiable appetite for new PowerPoint products. Decisions from our C2 organization often seemed nonsensical. I saw colossal amounts of waste due to bureaucratic inefficiencies. As Iraq began its slow spiral into insurgency and then civil war, my naive idealism eroded. I felt confused, disoriented, and unhappy.

Discontent is a normal part of a military career. I have seen many, many servicemembers undergo a similar process of disenchantment. Some never recover; they descend into cynicism and bitterness, then escape at their first opportunity. Others, however, undergo a transformation. They still feel restless dissatisfaction with the status quo, but they find a kind of inner peace, reframe their journey as a positive quest, and channel their frustrations into a career-long effort to improve the institution.

I eventually realized that discontent is a two-edged blade. It is one of your most important assets, but you have to wield it well.

Read the entire piece at From the Green Notebook.

The post Harnessing Your Discontent appeared first on Mark D. Jacobsen.

September 15, 2020

It’s OK to Love Your Family and Yearn For Meaningful Work