Bill Cheng's Blog, page 132

February 3, 2013

Mary Badham and Gregory Peck on the set of To Kill a...

Mary Badham and Gregory Peck on the set of To Kill a Mockingbird (1962). The two kept in touch after filming, and she continued to call him Atticus until the day he died.

jeffandkaren:

When I was 12 I read a book. It was called American Gods. It was about magic...

When I was 12 I read a book. It was called American Gods. It was about magic and religion in America. The book took place in Wisconsin. I lived in Wisconsin. I had never read a book about Wisconsin. I reread it about 20 times since. In the book, the main character had several adventures. He went to fictional places and fought battles. One of those places was called ‘The House on the Rock.’ It was a big house on the side of the highway. Inside were violins that played themselves, the world’s largest carousel, and a room filled with Santa dolls. There was the ‘infinity room,’ which jutted 30 feet out over a bluff. Its floors were made of glass. The driveway was lined with stone dragon statues, and the roof had Chinese-style tiling.

When I read about The House on the Rock, I knew that the author had never been to Wisconsin. Wisconsin had snow and fast food restaurants. We had farms and more farms. The population was 95% white. Nobody would build a place like that here. When I reread the book, I would imagine living somewhere that The House could exist.

Six years later, my class took a field trip to see Frank Lloyd Wright’s home. Our bus left at dawn. We crossed our state to the far western corner, a place I’d never been before. On the way, my teacher started talking about a special detour, but I was listening to music and missed what she said. I was staring out the window when I saw the first dragon.

I never read the preface. Not once during the rereads. The author had never said the house was fictional. But I assumed. The violins had robotic arms, which allowed them to play. The Santas scared my best friend. The carousel was not as big as I imagined. When I found the infinity room, I started crying. Afterwards we ate in the café. I don’t remember how the food tasted.

dragonsplash:

blaze-ferrari:

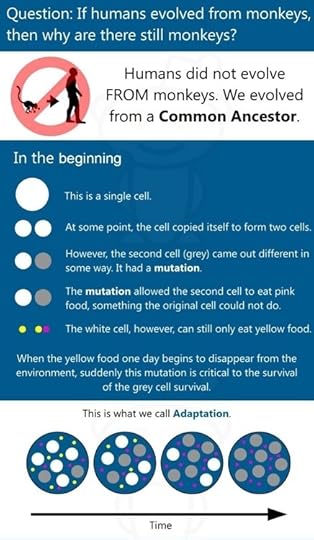

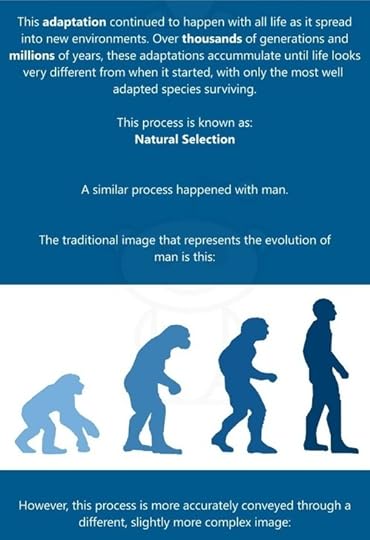

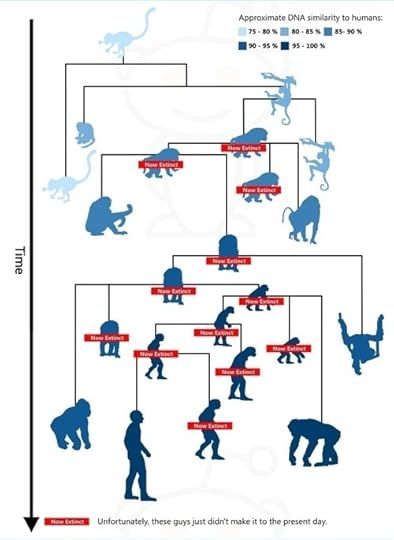

Evolution Simplified

This...

February 2, 2013

Happy Birthday, James Joyce!

February 1, 2013

theparisreview:

“[A]s far as I know, no sport has a more...

“[A]s far as I know, no sport has a more expansive vocabulary than football. And no sport has taken so many common words, stripped them of their original meanings, reinscribed them and fed them back into the English language as entirely different entities.“

Read more from Ariel Lewiton on the poetics of football here.

myimaginarybrooklyn:

Queens Library’s Langston Hughes Community Library and Cultural Center will be...

Happy Birthday, Langston Hughes (born on this date in 1902), we’re busy keeping your memory alive!

Hometown love!

myimaginarybrooklyn:

Post These Letters, Jeeves. Thanks, Old...

Post These Letters, Jeeves. Thanks, Old Bean.

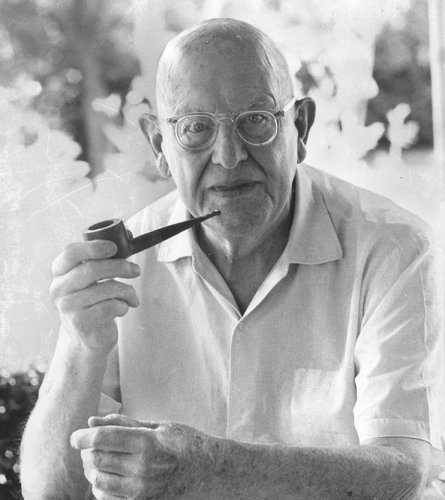

‘P. G. Wodehouse: A Life in Letters’

Writing to his agent in 1935, the comic novelist P. G. Wodehouse (1881-1975) proposed an essay about literary criticism that he planned to call “Back to Whiskers.” This piece is still worth rooting around to find.

His argument, Wodehouse declared, was that “the soppiness and overenthusiasm of modern literary criticism is due to the fact that critics are now clean shaven instead of wearing full-size whiskers.” He pined for the “brave old days when authors and critics used to come to blows.” Bring back, he cried, “the old foliage and acid reviews.”

Wodehouse was among the best-paid and best-loved writers in the world during the 1930s, a British institution, and he could afford to have a sense of humor about critics. He had found that “jolly old Fame” suited him.

His deliriously funny novels about the foppish and “mentally negligible” aristocrat Bertie Wooster, the imperturbable valet Jeeves and an enormous Berkshire pig named the Empress of Blandings, among other characters, were best sellers. He’d written Broadway musicals with Jerome Kern. He was fresh from Hollywood, where he’d composed screenplays and palled around with Mary Pickford and Edward G. Robinson. Oxford University had awarded him an honorary doctorate.

But things turned for Wodehouse during World War II. Imprisoned by the German Army, he recorded a series of radio broadcasts, intended to be funny and inspiring to those back home, that backfired badly. That his voice was on Nazi radio outraged his countrymen. He later admitted his “ghastly blunder,” but it took many years for people to forgive him.

Nearly as bad for Wodehouse, the world had changed. In his excellent biography “Wodehouse: A Life” (2004) Robert McCrum noted: “As George Orwell pointed out, Wodehouse became associated in the public mind with the wealthy, idle, aristocratic nincompoops he often wrote about, and made an ideal whipping boy for the left.”

This long, slow, painful shift in Wodehouse’s fortunes and reputation provides much of the heft and drama in “P. G. Wodehouse: A Life in Letters,” a definitive new collection of his correspondence edited smartly by Sophie Ratcliffe, a young Oxford academic. Wodehouse was an assiduous letter writer, often composing several a day, and there are missives here to everyone from family and friends to people like Ira Gershwin, Evelyn Waugh, Arthur Conan Doyle, Agatha Christie and George Orwell.

Wodehouse was not, alas, a very good letter writer. He isn’t reflective. He tends to ramble on numbly about his taxes, or his pets, or his daily schedule, or his fluctuating weight. The effortless humor that buoys his fiction (“Bicky rocked like a jelly in a high wind”) is largely absent here. He’s a bit of a wheeze.

I found myself cursing this book about halfway through its 602 pages; it felt like a concrete block tied to my ankle. My family cursed it too, because reading it I couldn’t help pick up some of the pre-World War I slang that Wodehouse adored and deployed. I found myself calling people “old bean” or “old fright.” Things suddenly seemed “ripping.” I announced my plans to “biff about in old clothes.” Kill me, I said, if I can’t stop.

If you shake “P. G. Wodehouse: A Life in Letters” hard enough, however, good things do fall out of it, like subway tokens from the pockets of a fuzzy old overcoat.

Wodehouse — it is pronounced WOOD-house — was a self-made man, and he never took his success for granted. He wrote constantly, wherever he was, often as many as 4,000 words a day. About being a jobbing writer, he learned he had to stick up for himself. “One has to beg for one’s money as if it were a loan,” he said about the freelance life, “instead of being one’s rightful earnings long overdue.”

His portraits of the famous are sometimes terrific. H. G. Wells, at a lunch, “sat looking like a crushed rabbit.” Wodehouse groaned at the enormous fireplace in Wells’s house, with letters carved around it that spelled: “TWO LOVERS BUILT THIS HOUSE.” He later, mockingly, put a similar fireplace in one of his Wooster novels.

Wodehouse was a deep admirer of Orwell, who wrote an essay in his defense after the radio debacle. But Orwell wasn’t his type. After Orwell’s death Wodehouse wrote: “He struck me as one of those warped birds who have never recovered from an unhappy childhood and a miserable school life.”

He could be very dense about politics. As late as 1939 he suggested that “the world has never been farther away from a war than it is at present.” He did not like change. About Cambridge University he said in 1962: “I think they’re all wrong making the standards so high.” He thought admissions should be based on “charm of manner.”

In the 1950s and ’60s the literary world began to baffle him. After reading Norman Mailer’s novel “The Naked and the Dead” (1949) he wrote: “Isn’t it incredible that you can print in a book nowadays stuff which when we were young was found only on the walls of public lavatories.”

He began to be less sanguine about his own critics. “Now I am like a roaring lion,” he said in 1953. “One yip out of any of the bastards and they get a beautifully phrased page of vitriol which will haunt them for the rest of their lives.”

The world came back around to P. G. Wodehouse, however. Upon his 80th birthday a notice appeared in The New York Times from writers including John Updike, Lionel Trilling, W. H. Auden, Nancy Mitford and James Thurber. He was measured for Madame Tussaud’s. He was knighted in 1975, the year he died.

The best place to meet this man is in his novels or in Mr. McCrum’s biography, not here. But even in this arid book he seems, to borrow one of his favorite locutions, like an awfully good chap.

I was introduced to the Jeeves books by a friend of a friend of a friend— ostensibly a stranger— at a party. It was a rough time in my life and she told me that whenever she was feeling down, she reads Wodehouse. I do the same thing now. And for that I am grateful.

noseinabook:

Books That Changed Me

thegirlandherbooks:

Hey Bookporners!

lothlorienlady wants to...

Hey Bookporners!

lothlorienlady wants to invite us all to participate in her new project: Books That Changed Me.

A blog where people can submit stories about books that have touched them in some way.

I think this is a beautiful project and I’ll participate for sure ^_^

Hope you join and spread the word!

Quien Es Esa Chica - Bookporn Team.

Really, really cool!

January 31, 2013

Vertigo App

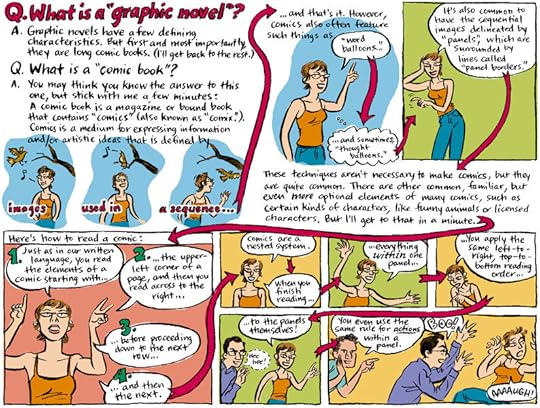

I’ve been re-reading Neil Gaiman’s Sandman series. Since all my old comics are in my parents’ basement, I’m using the Vertigo app (powered by ComiXology) on the iPad and re-purchasing each issue one by one. The app is great. It has a feature where it can focus in on one panel at a time before fluidly moving onto the next panel with a touch which is great for someone like me.

You see, I never really learned to read a graphic novel.

When I’m reading a graphic novel, I feel like two areas of my brain are trying to activate at once— one region to process the images and the other to process the text. It’s overwhelming and I find that more often than not, the image-center cedes power to the text-center. As a consequence I glean only the most essential information from the corner of my eye— who is in the panel? what are they doing?— before racing to the next letterbox or dialogue bubble.

For me, the text sets the pace. I imagine that’s the case for most people. After all, that is the most explicit way in which the narrative in this medium unfolds. And that is a damn shame!

I can’t find a creative commons example to show you but this is from the first panel of the first page of Sandman #1.

Let’s take this layer by layer: On the foreground is a metal gate, abutted on the left by a pillar and the grotesque of some stone dragon-looking thing. Beyond the gate is what is probably a turn of the century motorcar leading up to a nasty looking villa. The front of the villa is pocked with these splintery bushes. The villa itself is made up of several narrow looking gables. Centered is a raised rectangular structure with a round ovoid window— shimmering— like a cyclop’s eye. The structure is flanked on both sides by two nasty looking prongs like devil ears. Behind the villa you can see the tops of trees cracking through the sky and a pair of birds taking off toward the upper-right of the panel.

The panel was penciled by Sam Kieth and inked by Mike Dringenberg. It’s quite beautiful and quite deliberate in its layout and detailing and tone.

With the app, my eye is finally being trained not to anticipate the next panel but to better absorb the information presented to me.

I don’t know if there is a lesson here for eBooks, but it does make me wonder about the craft of writing for graphic novels. The standard maxims of show don’t tell probably don’t apply in the same ways, and one is likely mindful of how redundant some information is, or the pacing of your words.

I don’t know. I wish I did.

penamerican:

US Department of State Unveils Arabic Open Book Project

Earlier today, US Secretary of...

:

US Department of State Unveils Arabic Open Book Project

Earlier today, US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton unveiled the Open Book Project (remarks, project page, press notice), an initiative to expand access to free, high-quality educational materials in Arabic, with a particular focus on science and technology. These resources will be released under open licenses that allow their free use, sharing, and adaptation to local context.

The initiative will:

Support the creation of Arabic-language Open Educational Resources (OER) and the translation of existing OER into Arabic.

Disseminate the resources free of charge through project partners and their platforms.

Offer training and support to governments, educators, and students to put existing OER to use and develop their own.

Raise awareness of the potential of OER and promote uptake of online learning materials.