Man Martin's Blog, page 119

August 6, 2014

Did Lower Testosterone Lead to Civilization?

Although humans have been around for 200,000 years, they didn't develop the makings of modern society -- culture, art and advanced tools -- until about 50,000 years ago...The journal Current Anthropology finds that human skulls changed shape at about that same point in time -- physical changes linked to declining testosterone levels. The researchers say that suggests lower levels of the male hormone could have helped bring about modern civilization. - CBS News

Although humans have been around for 200,000 years, they didn't develop the makings of modern society -- culture, art and advanced tools -- until about 50,000 years ago...The journal Current Anthropology finds that human skulls changed shape at about that same point in time -- physical changes linked to declining testosterone levels. The researchers say that suggests lower levels of the male hormone could have helped bring about modern civilization. - CBS NewsThere was a time I would've just wanted to smash your head in, I mean it. I'm sorry, but that's just the way it was. Smashing heads in was like my favorite food or something. Just about the only reason I'd even tolerate your company was if we were smashing in the head of something else together. Like a mastodon. It's a total rush smashing in a mastodon head. Don't get me wrong, I still would love to smash me a mastodon head, and even looking at your head right now, there's a part of me that thinks, boy, it'd be fun to smash that in. I can just hear that sound - kngorscch - kind of crunchy and goopy at the same time when you smash in a head, you know?

But, I don't know, I don't enjoy smashing in heads any less than I used to, but now there's these other things, too. And it's so much better. Like, my mate for example. It used to be, I just wanted to mate with her, then as soon as I was done, I'd go off looking for heads to smash in. It was like, I had to go off because if I stuck around, sooner or later, I'd notice she had a head, then, kngorscch. But the other afternoon, after I finished mating, I hung around a little. She asked me about my day and if I'd smashed any good heads lately, and it felt great. Then she told me about her day, and I actually listened awhile before I realized if I stuck around any longer, I'd have to smash her head in.

Like you take that cave painting we did. Do you think we could have done that if we'd been busy smashing heads in? Definitely not. I'd have been like, "Why'd you screw up that bison? You gave it six legs! A bison has at most three to five legs!" And I'd have smashed your head in. Now, you know what? That screwed-up bison is my favorite part of the whole painting. Seriously, dude.

Anyway, that was just something I wanted to get off my chest. I think I'll pick up this big rock and get up and walk around a little bit. No, don't get up. Sit right where you are. I'm just going to carry this big rock - boy, it's heavy, too, ha-ha - over here behind you. La-de-da-tumty-tum-tum. Just stay right where you are. Right. Where. You. Are.

Published on August 06, 2014 04:01

August 5, 2014

Life is so Much Easier

If Ben Franklin wanted to watch TV,

If Ben Franklin wanted to watch TV, he had to start by cutting down a tree.Thanks to technology, life is so much easier than it used to be. These days, if my daughter wants to send a text, she just whips out the ol' phone and - boop-beep-boop-beep-boop- text sent. (Of course, phones don't actually go boop and beep anymore, but I had to do something to signify action being taken.) If I want to send a text, I just say, "Spencer, send a text for me," and - boop-beep-boop-beep - done.

But think about my grandmother. If she wanted to send a text, she had to get out some yarn and do needle-point. It took hours for Meemaw to created a simple text like, "WTF" or "LMAO." And no spell-check, forget about that. If she needle-pointed CUL7R instead of CUL8R, it either stayed that way or she had to re-do the whole thing.

Or you take GPS. I love my GPS; I used to get lost all the time. Do you think my great-grandparents had GPS when they were traveling to Montana in a covered wagon? Hecks no. It was a covered wagon. For GPS, you had to depend on strangers. They'd ask some settlers along the way or some friendly-Indians, "Do you know the way to the Conestoga Pass?" And everybody would stare at each other, and someone would say, "Recalculating... Recalculating..." and sooner or later - if you were lucky - they might say, "Turn around when possible," or if you were really, really lucky they might say, "Five hundred miles and you have reached your destination. On left."

And streaming TV, whoa! These days I can turn on TV anytime I want and watch Orange is the New Black, which features an average of one simulated lesbian sex scene per 1.5 episodes. Talk about convenience. Like Ben Franklin, he was pretty smart, right? But if he ever thought, "I'd like to watch a simulated lesbian sex scene on streaming TV," you know what he'd have to do? Well, first of all, he'd have to write his own episode to get some people to act it out for him. Then he'd have to get one of his buddies to invent a camera for him so he could film it. But that's not all. Then he'd have to chop some wood, grind glass, and maybe dig up some lumps of coal so he could build a TV to watch it on. But no so fast, buddy! There's only one simulated lesbian sex scene per 1.5 episodes - and if he happened to write an episode without a simulated lesbian sex scene, he'd have to start the whole process all over again.

So just be grateful you're not Ben Franklin but you can turn on TV anytime you want and every 1.5 episodes see a simulated lesbian sex scene.

Published on August 05, 2014 04:16

August 4, 2014

Are You Hearing This, Honey?

This is especially frustrating because I happen to

This is especially frustrating because I happen tobe an excellent listener.A study shows that men find women who listen to them sexier than women who don't listen.

I am not doubting the conclusions of this study, but it sounds like the sort of thing concocted by men who were getting tired of being ignored by wives and girlfriends.

I cannot tell you how many times I have posed a question to my darling wife only to have it hang there in space like a levitating potato waiting for a reply that never came. Sometimes I will repeat the question; others I will decide I didn't need an answer that badly in the first place. In case you think I am making this up, this has been witnessed by outside observers. I once asked Nancy a question in the presence of her sister Donna. Donna looked at Nancy waiting for her reply, then looked at me - is she going to say something? - then back at Nancy again, and then at me. Finally, the suspense was too great. She asked the question again herself.

It isn't as simple as just repeating the question because sometimes Nancy is making up her mind how to answer, and if you jump in with the question too soon, she's likely to be irritated. This may be a congenital trait. Her father can be extraordinarily slow at framing his words. I have heard Obama throw in some pretty weighty pauses as he carefully chooses his next word, well, compared to Nancy's dad, Obama is a piker. He will begin a sentence and then come to a complete standstill as he searches his data banks for the precise phrase or adjective he wishes to employ regarding, say, the mutilation and repair of garden hoses. A few words deeper into the sentence, and he will hit another roadblock. I am not proud to admit this, but I've taken to silently counting to see how high I can get before the next word comes out. I've gotten as high as 17. Not the most respectful thing to do, but it fills the idle moments of conversation with Dad.

But back to the main point which is Nancy's - and as I suspect from this study, many women's - failure to listen to their significant others with sufficient absorption. This is especially frustrating for me because I happen to be an excellent listener. I make it a practice not only to go "uh-huh" at intervals but to nod my head in agreement or at least acknowledgement. When I'm really at the top of my form, I can even isolate key phrases and say them back as questions, as if in disbelief. "A garden hose?" For example, Nancy left for the week and said several things to which I did an outstanding job listening. I not only said, "Uh-uh," and nodded my head, I sometimes said, "Got it," or "Right." It was something I was supposed to do or not do while she was gone. Either turning something off, or turning it on, or else possibly not turning it off. I'm pretty sure it either had to do with the dog, the washing machine, or the dishwasher. I'm ninety-percent sure it had something to do with water. It definitely did not relate to electricity, except in the most tangential way. Whatever it was, she seemed to think it was pretty important.

Maybe it was something to do with the garden?

Published on August 04, 2014 03:58

August 1, 2014

Why English is Such a Mess: The Final Chapter, People

English would be fine, except people keep

English would be fine, except people keepusing it to talk.Why is dough pronounced doe and tough pronounced tuff? Why is it one mouse, two mice, but not one house, two hice? Why isn't one grain of rice, a rouse? Why do people say, "Pardon my French," when they swear? Why is Leicester pronounced Lester? Why is it wrong to carelessly split an infinitive and why can't we use no double negatives? In short, why is the English language such a mess? Over the next few blogs I will explore this question.

When you get right down to it, the main reason English is so fouled up, is it keeps being used by people. Language would be fine if we could only just leave it alone, but people keep using it to talk. This leads to no end of trouble.

To start with, everytime someone does something unusual, we just turn his name into a new word. And almost always it's a word for something bad. Barney is a nice friendly dinosaur and Barney Rubble was a very friendly and helpful neighbor, but does Barney make it into the lexicon to mean friendly? No, he does not. Whose names turn into words? The Marquis de Sade, Judge Lynch, Leopold von Sacher-Masoch, and Joseph Guillotine. At this rate, every possible baby name will become unusable because of the unsavory behavior of some fore-bearer. How many little Caligulas, Adolphs, or Judases do you run into?

Admittedly, some of these eponymous words aren't so bad: pasteurize, mesmerize, and tantalize. Sandwich comes from the Earl of Sandwich who supposedly invented it to leave one hand free for dice-throwing. And then there's Sir John Crapper who helped pioneer the flush-toilet. And sideburns from General Burnsides, which brings up another way we screw words up: metathesis.

Metathesis is when we transpose sounds - like the way some people say, "noo-cue-lar" for "nuclear," or kids say "pa-sketti" for "spaghetti." Metathesis is like making a funny face, if you do it too often, every once in awhile it sticks that way. Like sideburns, or butterfly - which is a completely nonsensical name for an insect until you know it was originally and more logically a flutter-by. We may ridicule people for saying "aks" instead of "ask," except "aks" was the way it was originally pronounced before it metathesisized into "ask," and it seems on its way to metathesisizing back again.

Metathesizing isn't really a word, but it's just another way we mess things up; we take things we think are prefixes and suffixes off words to make other words, only the prefixes and suffixes weren't really prefixes or suffixes at all, and we're accidentally creating whole new words.

This is called back-formation. For example, some people take conversation and make a verb out of it, conversate. That may sound silly to you now, but a lot of the words you use all the time were back-formed (there's an example right there) from other words. Everyone knows butler gave us buttle, and burglar gave us burgle, but did you know gambler gave us gamble, and foggy gave us fog? But that's different you say, those are actual words, or at least their back-formation was logical and neccessary. Well, they weren't words until people thought they were. And their creation was no more logical than making ham out of hammer or mug out of muggy.

And on top of that, even when we don't change the pronunciation of the word, we keep changing its meaning. You can laugh at someone for saying irregardless, but why don't we laugh at inflammable? Oversight, does that mean to fail to notice something or to pay it extra close attention? Nice used to mean weak or stupid, but now it's something good. Literally is fast on its way to meaning not literally. And moot, can someone please tell me what moot means? Does it mean worthy of discussion or completely irrelevant?

And we can't even leave the dead languages alone, but are forever digging them out of their graves and rearranging their parts. Monopoly literally means "one many." What kind of nonsense is that? And sophomore means "wise fool," and preposterous is "before-after."

Honestly, English is such a mess, sometimes I almost think we're making this stuff up.

Published on August 01, 2014 08:04

July 31, 2014

Why English is Such A Mess: Part Ten, The Americans

Mispelling has been a problem

Mispelling has been a problemfor Americans from the very begining.Why is dough pronounced doe and tough pronounced tuff? Why is it one mouse, two mice, but not one house, two hice? Why isn't one grain of rice, a rouse? Why do people say, "Pardon my French," when they swear? Why is Leicester pronounced Lester? Why is it wrong to carelessly split an infinitive and why can't we use no double negatives? In short, why is the English language such a mess? Over the next few blogs I will explore this question.

Why, for heaven's sakes, can't the English use English? The fact they spell color, "colour" is the least of it. I do a double-take when I read about some Brit being sent to gaol or having to fix a flat tyre. Gaol? Tyre? And the way they pronounce "controversy." God, can't they hear how silly they sound?

Separate people by a few thousand miles of salt water, and some changes are bound to take place, especially since the colonists were exposed to whole new things the English didn't have words for. Sometimes, they adapted a Native-American word: raccoon, moose, and squash - and sometimes they used an English word, only made it more specific. In America corn refers to corn on the cob. In England, until pretty recently, corn could be any grain.

English-speaking Americans, already using a corrupted dialect, got to mingle with the corrupted dialects of immigrants from all over Europe. From the Cajuns - a corruption of Acadian, ie Canada, we get boocoo, (beaucoup), and levee, and bayou - and from Pennsylvania Dutch, kindergarten, stoop, and cookie (they call it a biscuit in England). From the Spanish we get rodeo, stevedore, and barbecue.

The jury's is still out where we get the expression, "okay." That it stood for "Old Kinderhook," seems unlikely. It may be from Scottish - "och aye" - or Lakota - "hokaheh" - or Choctaw "okeh" - or West African, "waw key." My favorite etymology is it comes from President Andrew Johnson who initialed papers, "OK," and when asked why, explained it stood for "Oll Korrect."

The fact is, that while we beat the British in the Revolution, they're still more than a match for us when it came to spelling. We can barely get our heads around, "I before E except after C or sounding like A as in neighbor and weigh. Oh, except for weird. And their. And Keith." We're stumped that St. John rhymes with engine, and Wooster is pronounced Worster, and could never learn to spell "Foshay," the way they do in England, which is Featheringshaugh.

When it comes to English, let's face it, you can't beat the English.

Take for example this little note Wellington jotted off one day:

"I see that the fire has communicated from the haystack to the roof of the château. You must however still keep your men in those parts to which the fire does not reach. Take care that no men are lost by the falling in of the roof, or floors. After they will have fallen in, occupy the ruined walls inside of the garden, particularly if it should be possible for the enemy to pass through the embers to the inside of the House."

Pretty nifty, huh? Did you notice how he slips in the future-perfect tense "will have fallen" not to mention the subjunctive, "if it should be possible"? I bet you didn't even know there was a future-perfect tense. Bear in mind, he whipped off this little missive during the heat of battle at Waterloo, when he might have been excused for forgetting the circumflex on château.

Compare that to a journal entry by George Washington written in perfectly calm reflection at his own desk in Mount Vernon:

"Went a hunting with Jackie Custis and catched a Bitch Fox after three hours chace - founded in ye CK. by J. Soals."

"A hunting" might be acceptable 18th-Century English, but what about chace, and founded, and catched? Catched?

No wonder the founding fathers were so big on simplified spelling. Noah Webster's dictionary came out about 50 years after Johnson's version across the pond. Noah's had a couple of things Johnson didn't - for example, the letter J. It also had center instead of centre, plow instead of plough, neighbor instead of neighbour, donut instead of doughnut, and tung instead of tongue.

Okay, the spelling of tung, didn't stick. But next time you and your neighbor pull off the thruway and stop at your favorite Kwik-Mart to check your tire pressure and maybe get a donut, just be glad you're an American.

Assuming you are American.

Published on July 31, 2014 08:46

July 30, 2014

Why English is Such a Mess: Part Nine, The Grammarians

"Or is it supposed to be 'Thou wilt not...?"Why is dough pronounced doe and tough pronounced tuff? Why is it one mouse, two mice, but not one house, two hice? Why isn't one grain of rice, a rouse? Why do people say, "Pardon my French," when they swear? Why is Leicester pronounced Lester? Why is it wrong to carelessly split an infinitive and why can't we use no double negatives? In short, why is the English language such a mess? Over the next few blogs I will explore this question.

"Or is it supposed to be 'Thou wilt not...?"Why is dough pronounced doe and tough pronounced tuff? Why is it one mouse, two mice, but not one house, two hice? Why isn't one grain of rice, a rouse? Why do people say, "Pardon my French," when they swear? Why is Leicester pronounced Lester? Why is it wrong to carelessly split an infinitive and why can't we use no double negatives? In short, why is the English language such a mess? Over the next few blogs I will explore this question.Anyone can make a mistake, but to really foul things up, you need an expert.

In 1589, William Bullokar wrote the first book on English grammar, which was a start, but other experts spotted the defects right away. For one thing, Bullokar had written it in English, which was the sort of mistake you'd expect from an amateur, but his successors corrected this by writing their English grammars in Latin, which anybody could see was a much more sensible approach.

By the 1700's you couldn't throw a brick without hitting an expert in English grammar. Grammarians are like lawyers. If there's only one, nothing much happens - it takes two or more on opposite sides to really get the ball rolling, and once you have a sufficient quorum, they can brings things to a complete standstill.

The reason for the profusion of these experts was a crying need to "fix" the English language, not fix in the sense of "repair," but in the sense of pin down, keep from moving. English had gone from, "Hwæt! We Gardena in geardagum," to "Whan that Aprill, with his shoures soote the droghte of March hath perced to the roote," to "What light through yonder window breaks," in just a few hundred years. Anyone could see that if this precipitous rate of change were left unchecked, English was capable of mutating into anything; why, someday people might be writing nonsense like. "lmao" or "C U L8R" or maybe just smiley faces and stuff. This had to be prevented.

The only catch was, if you're rooting around for official rules for a language that has no official rules, where do you turn? The answer, other languages. For example, mathematics. In many languages, such a Spanish, you can pile on as many negatives as you please without changing the meaning one iota. No me cuenta algo, "they don't tell me anything," means just the same as, No me cuentan nada, "they don't tell me nothing," which means the same as No me cuentan nunca nada, "they don't never tell me nothing;" although admittedly the last one starts to sound a little petulant.

But in English, if you say, "They don't tell me nothing," some wise-ass is bound to point out, "Well, that means they do tell you a little something." The reason two negatives make a positive in English is because that's what they do in mathematics.

Mathematics is all well and good, but the go-to source for the early English grammarians was Latin. Latin is a dead language, which makes it a perfect model for a living one. The problem with something so sprightly and fluid as a spoken language is it won't hold still long enough to get a really good look at, unless you wait for it to be in its coffin.

For example, you're not supposed to end a sentence with a preposition. Maybe that rule makes sense to keep us from saying, "Where are you going to?" instead of just "Where are you going?" but what if you need to ask, "What's this book about?" Are you really supposed to say, "About what is this book?" Ending a sentence with a prepostion is perfectly grammatical in most Germanic languages, and English is a Germanic language, but you can't do it in Latin, so you're not supposed to do it in English either.

Latin is also where we got the peculiar rule to never, ever split an infinitive. The reason you're not supposed to split an infinitive in English is because in Latin, you can't. The infinitive "to go" is two words in English, but in Latin it's just vadere. You can't say, "to boldly go" in Latin unless it was something like va-boldly-dere, whatever the Latin word for boldly would be, which I do not intend to look up. But in English you can split the infinitive, only you may not.

May and can is another one.

These words were used pretty much interchangeably until the 1600's when some grammarian decided can, which comes from a root meaning, "having the knowledge to do something," referred to ability, and may, from a root meaning "having the power to do it," referred to permission. But it is not grammatically wrong to say, "Can I go to the bathroom?" when asking permission. Do you hear that, Mrs. Othmar, my third-grade teacher? There's nothing grammatically wrong with it.

Anyway, the grammarians sought to help us out and bring order to the mare's nest of English language, and to a large extent they have given us useful rules to follow. But keep in mind, English is not math, and it's not Latin, but its own unique thing, and if some petty snoot wants to sneer at you for perfectly sound English that doesn't happen to conform with some arbitrary injunction set down four hundred years ago by some self-appointed expert, use the retort Winston Churchill made when someone tried to correct his grammar, "This is the sort of thing up with which I will not put!"

Published on July 30, 2014 08:34

July 29, 2014

Why English is Such a Mess: Part Eight, the Crusades

There was bound to be trouble.

There was bound to be trouble.

Why is dough pronounced doe and tough pronounced tuff? Why is it one mouse, two mice, but not one house, two hice? Why isn't one grain of rice, a rouse? Why do people say, "Pardon my French," when they swear? Why is Leicester pronounced Lester? Why is it wrong to carelessly split an infinitive and why can't we use no double negatives? In short, why is the English language such a mess? Over the next few blogs I will explore this question.

Whenever the One True Religion of an All-Good All-Powerful God runs into another One True Religion of an All-Good All-Powerful God, there's bound to be trouble. In the case of Jerusalem, it was claimed as sacred to the All-Good All-Powerful God of at least three different One True Religions, so you can just imagine the bloodshed.

The first Crusade was launched in 1096, on that everyone pretty much agrees, and they went on until 1291 give or take a couple of hundred years. Exactly how many Crusades there were is hard to say. Between seven and nine major crusades, and a lot of little ones. Like the Crusade of Louis IX, is he supposed to get credit for two Crusades or just one big Crusade? It's all very complicated.

Anyway, this brought English-speakers and a lot of other Europeans into contact with Arabic languages. Not surprisingly, we gained a lot of words had to do with military matters - a Saracen military commander was an amir, from which we get admiral. The "d" probably got stuck in there because people thought the rank meant we were supposed to admire him. Darsina, which was Arabic for manufacturer, became arsenal, and of course the ḥashāshīn, which wasn't really a religious sect, but a nickname for one, like "Quaker" or "Mormon," gave us assassin.

Check is such an Anglo-Saxon-sounding word, it's hard to believe it comes from, shah, king. An exchequer works for the king handling the petty cash drawer and the Christmas fund and what-not, and is entitled to write checks. In chess, we say, "check," when the king's in a pickle, and when he's completely cornered, it's "checkmate," from shah mat - the "king dies."

The Muslim world was way ahead of Western Europe in things like algebra and chemistry and gave us words like, well, algebra and chemistry. Zero, of course, is Arabic as are cipher, and azimuth, and zenith, and algorithm.

Then there were all those thing Westerners didn't have words for because Westerners had just never seen them - things like jasmine, harems, guitars, gauze, hashish, aubergines, tangerines, oranges, sugar, sherbet (and also syrup and sorbet) saffron, and gerbils.

The Crusades were a dark spot in history, but they did serve to enrich English culture and language in many ways. The last of the Crusades was 1296, I think I said, or maybe it was really closer to 1396, or it might have been 1456, but that was absolutely the last one, really. It took awhile, but we finally learned our lesson, I'm glad to say, and the West and the Middle East have been at perfect peace and haven't given each other a lick of trouble ever since then, thank goodness.

Published on July 29, 2014 06:16

July 28, 2014

Why English is Such a Mess: Part Seven-B, The French, The Freaking French

William the Conqueror begins introducing words to EnglishWhy is dough pronounced doe and tough pronounced tuff? Why is it one mouse, two mice, but not one house, two hice? Why isn't one grain of rice, a rouse? Why do people say, "Pardon my French," when they swear? Why is Leicester pronounced Lester? Why is it wrong to carelessly split an infinitive and why can't we use no double negatives? In short, why is the English language such a mess? Over the next few blogs I will explore this question.

William the Conqueror begins introducing words to EnglishWhy is dough pronounced doe and tough pronounced tuff? Why is it one mouse, two mice, but not one house, two hice? Why isn't one grain of rice, a rouse? Why do people say, "Pardon my French," when they swear? Why is Leicester pronounced Lester? Why is it wrong to carelessly split an infinitive and why can't we use no double negatives? In short, why is the English language such a mess? Over the next few blogs I will explore this question.So in the last episode, William the Bastard became William the Conqueror and comes over to be king of England. Even then, he might not have had that much impact on the language if the English lords had been able to get with the program and just deal with it, but oh, no, they had to go and make a fuss. And every time one of the Anglo-Saxon lords made a fuss, naturally, W the C had to have him rubbed out, and then he'd bring over a Frenchman to replace him, and then another lord would make a fuss about that, and he'd get rubbed out and a Frenchman would replace him. And this went on until just about everybody who was anybody was French.

The next sentence is so peculiar, I'm going to write it twice.

For hundreds of years, the official language in England was French.

For hundreds of years, the official language in England was French.

Everything that went on at the royal court - including the words "royal" and "court" - was conducted in French. Most of the hoity-toity set didn't even know English. The upshot was that if you were an Anglo-Saxon during this period, assuming you weren't rubbed out, you learned you some French as fast as you could learn it. When English re-emerged after this hundreds' years dousing with French, it was entirely transformed. For comparison's sake, here's the opening lines of Beowulf again, which as you will recall, are written in Old English, before the Norman Conquest:

Hwæt! We Gardena in geardagum, þeodcyninga, þrym gefrunon, hu ða æþelingas ellen fremedon.

What the freak, right? I mean, what the freakin' freak?

But now, here's the opening from Canterbury Tales:

Whan that Aprill, with his shoures soote the droghte of March hath perced to the roote And bathed every veyne in swich licour, of which vertu engendred is the flour...

I mean, that's much better, right? It's still goofy as heck, but you can hope to pick out a word here and there. In fact, after you study it for a while, you can actually read it. It's just the spelling really. It looks like it was typed by someone wearing oven mitts, or who'd gotten his hands on too much of that switch liquor, whatever that is. What's even more amazing is that Canterbury Tales was written only about 300 years after the Norman Conquest. English had changed that much.

In addition to making English more like English, the Normans introduced French as a prestige vocabulary. If you were going to plead your case to the local magistrate, you better not drag any of your dirty, vulgar Anglo-Saxon in there, but be sure to use your dainty, polite Norman French. If someone's trying to impress you, he won't say, "Go to the boss and get the work papers to fill out" (Anglo-Saxon) but "Proceed to the administrator and obtain the employment documentation for completion" (Norman French). Both sentences mean exactly the same thing, but French-derived vocabulary has a strong snob appeal for English speakers.

This applies to other fields as well. We like to use Greek or Latin words for our scientific vocabulary. If you go to your doctor - a good Latinate word from the root "to teach" - and say a perfectly sensible Anglo-Saxon sentence like, "My fingers is swole!" he'll diagnose - (from the Greek, "to know") it as "digititis," and you'll think, "Now, I'm getting somewhere," except what he said means exactly the same thing as my fingers is swole.

This even goes as far as the dinner table. I would be appalled (Norman French, "to turn white") if my darling wife told me we were having sliced pig for supper. Instead of the Anglo-Saxon word, she uses the more appetizing pork which comes from French. A cow is the animal in the field: chewing cud and pooping, but she changes her name from Anglo-Saxon to the Norman French beef when she's on the table. Chicken still gets to be chicken whether it's in a pen or a red-and-white bucket, but sometimes goes by the Norman-French equivalent, poultry. For some reason fish is fish and only fish whether it's in the water or breaded and fried. Maybe the French poisson, "fish," looks too much like poison to be very appetizing.

Norman French is also why we have so many dirty words. Or rather, it's why the dirty words in English are so much dirtier than the dirty words in other languages. Merde in French, is no more than a mild oath. I knew a Panamanian grandmother who called her grandchildren - affectionately - mierditas. Our Anglo-Saxon equivalents - the vulgar connotation of the language combined with the thing itself makes some words dang near unprintable.

Consider; I can say feces, excrement, and elimination - all Norman French. But I would blush to write a simple synonym that starts with s and rhymes with "pit." The s-word is Anglo-Saxon, therefore dirty. But would you stepped in something you thought was an Old English turd, would you really feel better to know it was Norman French excrement?

Fornicate, copulate, coitus, and sexual intercourse are all Norman French and all mean the same as the f-word, which is Anglo-Saxon, and therefore too naughty for this blog. (Roy Blount, Jr. also points out that the f- word happens to have a very ugly sound, like a boot being pulled out of mud.)

"Pardon my French," is kind of a joke because the person never says it after using Norman French, but Anglo-Saxon.

Published on July 28, 2014 14:04

July 27, 2014

Why English is Such a Mess: Part Seven-A, The French, the Freaking French

"Oh, that old thing?

"Oh, that old thing? That's just a Bayeux Tapestry."Why is dough pronounced doe and tough pronounced tuff? Why is it one mouse, two mice, but not one house, two hice? Why isn't one grain of rice, a rouse? Why do people say, "Pardon my French," when they swear? Why is Leicester pronounced Lester? Why is it wrong to carelessly split an infinitive and why can't we use no double negatives? In short, why is the English language such a mess? Over the next few blogs I will explore this question.

At this point English is about to get really messed up.

I don't know much about Edward the Confessor, but he must've been a real piece of work; before he died he managed to convince three people - two of them named Harry - that they should each be the king of England. Evidently, if you had dinner at Edward's place, sooner or later, he'd take you aside and say, "I got no kids, no heirs. You know who I want to be king of this joint when I kick it? You, bubby. I love you like a son, I mean it."

Before you go thinking these three guys were just a bunch of callous opportunists looking to glom onto a vacant throne, keep in mind, in a situation like this, when there's three people in the running, your chances, not of winning, but survival are only 33%. These guys each seriously thought he should be king of England.

"I just love being a horse."

"I just love being a horse."The story starts when Edward died and his brother-in-law Harold Godwinson assumed the crown. Meanwhile, though, another Harry, Harald Hardrada - (his last name means something like "hard head") - decided he should be king of England. Harald H. had finally given up after years of trying to conquer Denmark, when Tostig Godwinson, Harold G's brother (the other Harry, are you keeping track of this?) said, "Hey, why don't you be king of England. I'll throw my support behind you. The other Harold, I know he's my brother and all, but he's kind of a loser when you get down to it. I mean, just look at him." So Harald H. and Tostig set sail for England, arriving in the north, and Harold G. marches up to meet them.

Is that guy eating pizza?It only takes two battles to decide the matter, Harald and Tostig win the first round at Fulford, but Harold Godwinson prevails at a place called Stamford Bridge, and Harald and Tostig are killed.

Is that guy eating pizza?It only takes two battles to decide the matter, Harald and Tostig win the first round at Fulford, but Harold Godwinson prevails at a place called Stamford Bridge, and Harald and Tostig are killed.This occasioned great rejoicing among the Anglo-Saxons. For starters, there was one less Harry to keep track of, which made matters a whole lot simpler. Secondly, historically, Harald symbolized the last of the Vikings, so you can imagine the veterans slapping each other on the shoulder and saying, "We've symbolically killed the last symbolic Viking and symbolically the symbolic age of Vikings is symbolically over. Huzzah!" But then, just when they thought there was nothing but smooth sailing ahead, they learn William the Bastard has invaded England from the south.

Now you're going to have to cast your mind back to Part Two of this series, The Romans. The Romans never conquered all that far north, preferring to focus on shipping lanes, especially in the Mediterranean, remember? And the British Isles lie almost exactly at the midpoint where the Roman sphere of influence leaves off, and the Germanic people pick up, remember? Up to now, most of the folks invading England - Angles, Saxons, Jutes, Danes, and whoever else, were all Germanic. But William the Bastard came from just below the imaginary line of Roman influence, and spoke a Romance language: French.

"Bonk"Well, it wasn't French-French, it was Norman French. Normandy was so named because it was settled by Normans, ie North-men, ie Norse-men, ie Vikings. So after Harold defeated Harald, the symbolic last Viking, he had to face the descendant of another Viking, William the Bastard, only William wasn't speaking Old Norse, but some agglutination of Old Norse and Old French, got it? Jesus, I swear, history would be so much simpler if people quit invading each other and just stayed put.

"Bonk"Well, it wasn't French-French, it was Norman French. Normandy was so named because it was settled by Normans, ie North-men, ie Norse-men, ie Vikings. So after Harold defeated Harald, the symbolic last Viking, he had to face the descendant of another Viking, William the Bastard, only William wasn't speaking Old Norse, but some agglutination of Old Norse and Old French, got it? Jesus, I swear, history would be so much simpler if people quit invading each other and just stayed put.Anyway, someone had put it in William's head that if he conquered England, people might start calling him William the Conqueror instead of William the Bastard. So now the remaining Harold marched down, leaving many of his troops behind. He met William at Hastings where the future conqueror had thrown up a wooden fort. This was only a few weeks after the defeat of Harald the Hard-Headed.

Activities started around 9, on October 14, 1066. It was over in one day.

William sails back to Normandy, "Honey, I'm ho-ome," and his wife, Matilda, is like, "How was work today, honey?" And William's like (big grin) "Guess who has two thumbs and rules England? This guy!" And he points at himself with both thumbs, and she's like, "Darling, I knew you could do it!" And she hugs him, and starts talking about what she'll wear for his coronation.

Harold gets it.

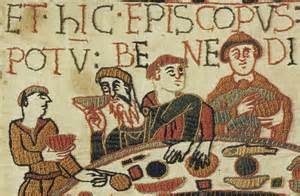

Harold gets it.Ka-Pweeng!I got a feeling Matilda was pretty obnoxious after her husband conquered England. She was probably one of those people who brags in a way that makes it sound like she's complaining. "Oh, there's so much to do, I can't even tell you how busy I am. We've got to change all the monogrammed towels from William the Bastard to William the Conqueror, and I've got to design a crown, and then there's all these people we'll be ruling - and not just the people, there's chattels, too. Oh, dear, and some of the people are chattels. it's all so complicated." Or else she'd be like, "Oh, that old thing? That's just a Bayeux Tapestry. It's a little thing I knitted Billy when he conquered England."

See, Matilda and her ladies in waiting decided to make a little tapestry to commemorate the victory, only once they got started, they just couldn't seem to stop. It's two-hundred-thirty feet long. There's lots of action and ships and people bonking each other with clubs, a comet goes by, and some people cook a meal, but the high-point as far as Matilda was concerned was the spot where Harold Godwinson gets it in the eye with an arrow. Matilda was a bloodthirsty so-and-so.

October 14, 1066 is one of those days when history pivots on its axis. Harold was at a disadvantage, having marched all those miles and having fought two battles already, but things could easily have gone the other way. There's no reason William couldn't have gotten an arrow in his eye, and then we'd still be speaking who knows what, but not what we speak today, whatever that is. The effects of the Norman Conquest are so profound, I can't squeeze them into today's blog, so we'll have to do more tomorrow.

Published on July 27, 2014 08:48

July 26, 2014

Why English is Such a Mess: Part Six, The Vikings

Clearly, This Guy is not a Real VikingWhy is dough pronounced doe and tough pronounced tuff? Why is it one mouse, two mice, but not one house, two hice? Why isn't one grain of rice, a rouse? Why do people say, "Pardon my French," when they swear? Why is Leicester pronounced Lester? Why is it wrong to carelessly split an infinitive and why can't we use no double negatives? In short, why is the English language such a mess? Over the next few blogs I will explore this question.

Clearly, This Guy is not a Real VikingWhy is dough pronounced doe and tough pronounced tuff? Why is it one mouse, two mice, but not one house, two hice? Why isn't one grain of rice, a rouse? Why do people say, "Pardon my French," when they swear? Why is Leicester pronounced Lester? Why is it wrong to carelessly split an infinitive and why can't we use no double negatives? In short, why is the English language such a mess? Over the next few blogs I will explore this question.There are a lot of misconceptions about Vikings. People think they were a bunch of blood-thirsty marauders who wore helmets with horns and went around raping and pillaging. The time has come to put a stop to this nonsense. The Vikings did not wear helmets with horns. If you think Vikings had helmets with horns, you're just living in a fool's paradise.

When it came to the other stuff, the Vikings were all over it: raping wives and daughters, burning crops, and carrying off livestock - and any other permutation of the preceding nouns and verbs you care to name. One thing the Vikings loved was a good monastery. A monastery was like ice cream to Vikings, especially if it had priceless works of religious art and stuff.

Rape and pillage is all well and good, but sooner or later, you want a regular job. The Vikings eventually decided instead of raping other men's wives and daughters and stealing their crops and livestock, they'd just move in, have their own wives and daughters, crops and livestock, and thereby cut out the middleman. After this, they stopped being Vikings and began being Danes.

When the Danes started moving in, it was a good thing and a bad thing. It was a bad thing if you happened to occupy the real estate they had an eye on, but it was a good thing because it was marginally better being neighbor to a Dane than an out-an-out Viking. With a Dane, you could hope to reason with him. You could say more than, "Take my wife, please, but don't stab me with that... arggghhh." The catch is, if you were going to talk with a Vik- excuse me, Dane, you had to be able to talk.

What the Danes spoke was Old Norse, only, naturally, they didn't call it that, and I don't know what they did call it, so don't ask. The catch was, Old Norse was very, very similar to Old English, but not exactly. Think of a Mexican talking to a Brazilian, something like that. You can make yourself understood provided you aren't too persnickety about grammar.

The heading on this blog promises to answer why we say "mice" instead of "mouses" and "geese" instead of "gooses." A better question is why there aren't more even more wierd-o plurals. Why don't mothers - excuse me, mothern - say, "Children put on your shoen before you ride the oxen, or you might poke out your eyen." The fact is, that's exactly what an Anglo-Saxon might have said, in an admittedly bizarre set of circumstances.

Old English had several sets of words, each with its own rules for pluralizing. Some, you just added a good old -s to the end, like microwave ovens and emoticons, and some you changed the vowel sound of, like men or mice and geese, and some you added an -n to, like oxen and children and brethren. But it used to be, there were a lot of words in each of these groups, but after the Danes, not so much. If your Danish neighbor asked you, "How much do you want for those horses of yours?" you wouldn't say, "That's horsen, you dolt, you're using the wrong declension," unless you wanted to see him forget his manners and go all Viking on your ass.

At the end of the day, the grammar of Old English simplified and became less synthetic and more analytic. In short, it mattered less what form a word took, than its position in the sentence. This process of simplification when one language comes in contact with a related, but different, one, is called rubbing. And when it comes to rubbing, no one did it better than the Danes, with or without horned helmets.

Published on July 26, 2014 03:55