Robert Levy's Blog, page 46

November 2, 2014

hedgerowdevil:

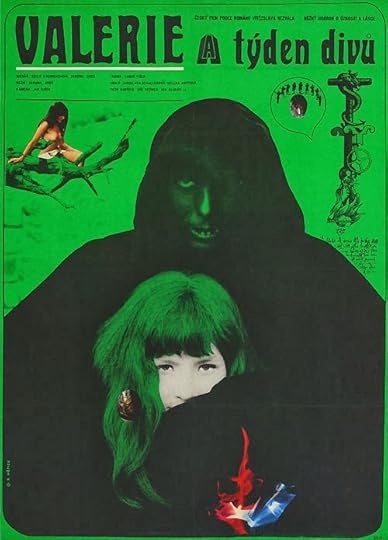

Valerie and Her Week of Wonders (Jamoril Jires,...

Valerie and Her Week of Wonders

(Jamoril Jires, 1970)

Blu-ray review.

This surreal coming-of-age fable drowns in a dense, drowsy fairytale vibe.

A young teenage girl spends her days dreamily wandering about her village, until that is she spots droplets of blood on the petals of a daisy. From then on, her world is taken up with the enticement of adulthood, which primarily takes the form of a vampire in a weasel mask.

A huge influence of Angela Carter and her 1984 film The Company of Wolves, which itself is an overripe sexual-awakening allegory set in a stylised storybook world. Valerie and Her Week of Wonders uses an Alice in Wonderland-like dream-logic and gorgeous, fantastical imagery in place of a conventional narrative. And 13 year old Jaroslava Schallerová is suitably ethereal as Valerie; taking the eroticism and the strangeness of her adventures in her stride.

As beautifully bizarre as it is entrancing.

October 31, 2014

October 29, 2014

Is the Giving Tree a Chump?

In May, the New York Times Book Review's “By the Book” column asked the author Leah Hager Cohen about the worst book she had ever read. Her answer? Shel Silverstein’s The Giving Tree. “I cannot understand why this book, which sentimentalizes entitlement, benightedness and contempt, became a classic of children’s literature,” she pronounced, with what I took to be self-righteous certitude.

I was astounded by her response. The Giving Tree? The beloved book of my childhood that I read to my own children today, stifling tears at its bitterly ironic message of ecological consumption and mindless greed? How could Silverstein’s parable be so woefully misinterpreted as a straightforward tale extolling the virtues of selflessness and sacrifice? Does anyone really think Silverstein intended his readers to happily accept that the tree, reduced to a mere stump at the story’s conclusion by the boy’s relentless taking, should truly be pleased by the boy’s actions, and that we should be as well?

Apparently so. One quick online search laid bare a vocal and passionate presence of The Giving Tree haters who virtually high-five one another over their shared disdain of the book. “This book reeks of the patriarchy,” a Goodreads member wrote in her one-star review. “Keep it away from your kids—especially your daughters.” A blogger on LiveJournal argued that it “romanticizes self-destructive and self-negating behavior in women… [T]he boy is a self-centered chauvinist who abuses the tree to the point of destroying it.” After reading similar accounts of deep loathing—mostly from women—I could no longer read the book in quite the same way, a shadow cast over my once unshakable interpretation. My own self-righteous certitude had been duly punctured.

This month marks the fiftieth anniversary of The Giving Tree. Published in 1964 by Harper & Row, the story of a boy and his tree (or is it a tree and her boy?) wasn’t an immediate success. Its sales grew steadily, however, and soon the book became a perennial bestseller. The Giving Tree has gone on to sell many millions of copies, with over ten million in print. Its cover illustration of the tree dropping an apple down to the boy has become its own iconic image, one you can find on cell phone cases and laptop decals that cleverly incorporate the Apple logo into the cover’s design. No less a cultural force than Bart Simpson has weighed in on the book, when, as part of a running gag on The Simpsons, he is made to write “the Giving Tree is not a chump” repeatedly on his classroom chalkboard in the opening credits of a 2002 episode.

Even those who fail to find irony in its pages are divided by The Giving Tree's intended effect. For every reader who chafes at the story as a sincere ode to unwavering self-sacrifice—gendered or otherwise—there is another who views the tree's boundless ability to give of itself as a virtue to be celebrated, if not imitated. This selflessness the tree exhibits is often seen as the very embodiment of the particularly Christian virtue of charity, or as an act of parental (specifically motherly) duty and ego suppression. Indeed, many first learn of The Giving Tree and its supposed message of self-sacrifice as a moral lesson in Sunday sermons and classrooms, a paragon of the principal that it is better to give than to receive.

But what does it really mean? It’s a question we often find ourselves clamoring to answer, as readers as well as filmgoers, television viewers and audience members, when we find ourselves unsteady in our own judgments, and haven’t already made up our minds. Silverstein, undoubtedly to his credit, refused to explain or excuse his work, especially this oft-discussed story. “It’s about a boy and a tree,” was all the author had to say by way of plot summation, as recounted in the 2007 biography A Boy Named Shel. “It has a pretty sad ending.” What are were we to do, then, with no concrete answers from the owner of the face on the notoriously anguished author photo on The Giving Tree's back cover? Perhaps it is as Oscar Wilde wrote in his preface to The Picture of Dorian Gray: “There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well written, or badly written. That is all.”

Still, I return to the undercurrent of irony I find so palpable in the story, a tone so seemingly absent in the eyes of so many of its readers. Part of The Giving Tree's lasting power rests in the tension between the cartoonish simplicity of the drawings—not much more than sketches, really, black ink minimally unfurled over stark white pages, only its cover in bold green and touches of red—and the brutal dismantling of the tree. The same is true of the story's words, whose ease of language isn't melodic so much as hypnotic. “Come, boy,” the tree repeatedly invites, to climb, to play, to take. In the end, the boy, now an old man seated upon the tree's stump, wears a ghost of a smile, his eyes shocked wide and haunted.

As for the issue of sentimentality that Ms. Cohen raises, does the adorability of the drawings ennoble the actions they depict? What does this say about other illustrated works such as Art Speigelman’s holocaust graphic novel Maus, or Barefoot Gen, Keiji Nakazawa’s manga series about a young Hiroshima survivor? Perhaps the concern arises because The Giving Tree is a children’s book and therefore susceptible to accusations of indoctrination, that kids—specifically, boys—will grow up to become takers. And if Silverstein didn’t intend for the book to be read as a skewed examination of gender roles, his cause is hardly helped by the fact that he was a notorious bachelor and a Playboy Mansion regular for many years.

In July, The Giving Tree became the answer to a different question in the “By the Book” column. Lynne Cheney cited it as the last book that made her cry, and added “I have to steel myself before I read it to my grandchildren.” Whether Ms. Cheney cries because she finds poignancy in the tree’s selflessness, or rather in its exploitation, is a question all its own. The child psychologist Bruno Bettelheim, in his 1976 landmark study of fairy tales The Uses of Enchantment, implored adults not to elucidate such stories to children, only to share them. “We grow, we find meaning in life, and security in ourselves,” he wrote, “by having understood and solved personal problems on our own, not by having them explained to us by others.” The meaning behind the book flared up yet again in the Book Review this month, when Anna Holmes and Rivka Galchen debated The Giving Tree’s merits in the Bookends column under the title “The Giving Tree: Tender Story of Unconditional Love or Disturbing Tale of Selfishness?”

We live in an age of questioning, however—Ask the author! Tweet the showrunner! Q&A after the screening with the director!—and one can’t help but wonder whether an artist’s license to traffic in ambiguity is slowly slipping away (just ask David Chase, who still makes headlines each time he reluctantly addresses the uncertain finale of The Sopranos). Perhaps as readers we’re trained to find parables in stories, even when they might not exist.

There’s no more asking about The Giving Tree, though; Silverstein died in 1999, and the farthest he seemed to have gone in terms of explicating anything close to his own intentions regarding the book’s message was to say that “It’s just a relationship between two people; one gives and the other takes.” In never satisfying our craving for explanation, Silverstein followed Bettelheim’s edict, thus ensuring that, for good or ill, The Giving Tree would keep on giving—and its ever-aging boy, taking—for many years to come.

October 28, 2014

books:

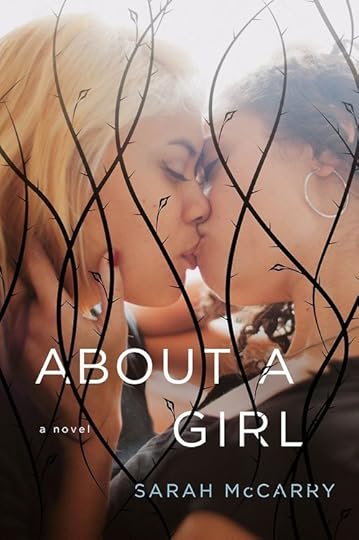

“It was hugely important to me that the cover accurately...

“It was hugely important to me that the cover accurately reflect the book’s two central characters, both of whom are girls of color (well, Medea is technically 3,000 years old, but she looks like a girl in the book), and the romance between them is a central focus of ‘About A Girl,’” McCarry said of the cover. “The extraordinary AIDS activist Pedro Zamora kissed his boyfriend on-screen (on MTV!) in 1994. I think 20 years later we should probably be able to handle girls kissing on a book cover.”

McCarry and Co. didn’t use a stock image to create the arresting cover, but, instead, worked with photographer Sandy Honig and models Lola Pellegrino and Kimmie David to create the photo.

(via 'About A Girl's Same-Sex Kiss Cover Should Be The Norm - MTV)

Very proud of these lovely and amazing words about my novel from...

Very proud of these lovely and amazing words about my novel from the lovely and amazing Joanna Rakoff:

"If you value sleep, you might want to think twice before you pick up The Glittering World: This deeply original, deftly plotted novel will keep you up until dawn, unable to tear yourself from its grasp. The Glittering World is that rare thing: A literary novel that reads like a thriller. A fairy tale for the modern era.”

— Joanna Rakoff, author of A Fortunate Age and My Salinger Year

October 25, 2014

sixpenceee:

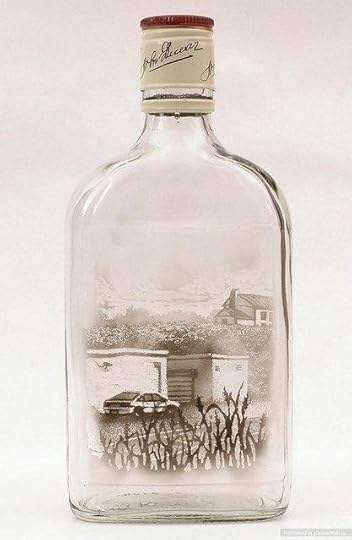

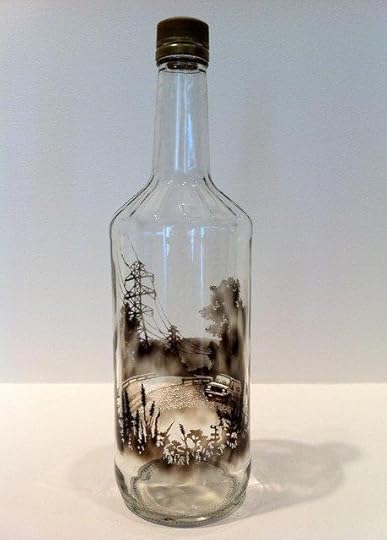

The Bottled Smoke Artwork of Jim Dingilian. He...

The Bottled Smoke Artwork of Jim Dingilian. He uses candle smoke to paint picture-perfect images on the inside of empty bottles. After laying a coat of soot on the lining of the bottles, the artist wipes and etches away with skewers and needles to construct the meticulously defined landscapes.(Masterpost of Creepy & Cool Art)

October 22, 2014

blkstiletto:

NYC Goth, Propaganda Magazine

source

October 16, 2014

Robert Levy’s The Glittering World is that rare and...

Robert Levy’s The Glittering World is that rare and wonderful kind of book that takes something old and makes it new again. Like those who disappear into the woods in this novel, once you step into these lush and mysterious pages, be prepared to return to your own world altered.

— Christopher Barzak, author of One for Sorrow

The Talented Mister Barzak, whose work I have long admired (his novels are revelatory, as is his recent short story collection Before and Afterlives), expertly hones in on the dark and contemporary fairy tale aspect of my book. In its own way, my novel is a postmodern retelling of Hansel and Gretel, and it took his kind words to make me remember why I decided to write it in the first place. Thanks, Chris!

maudelynn:

"Some people don’t sleep at night - I am one of...

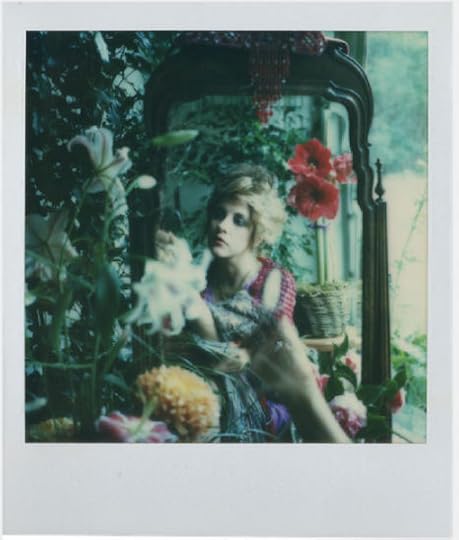

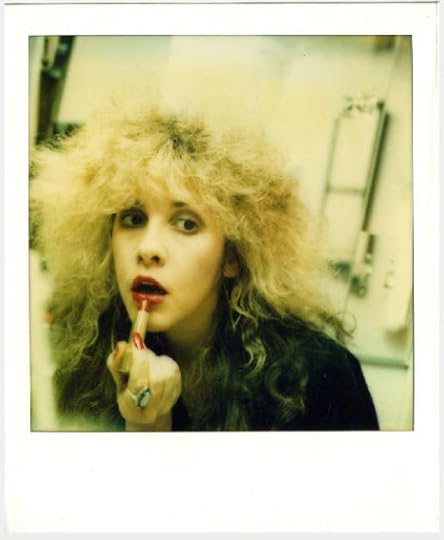

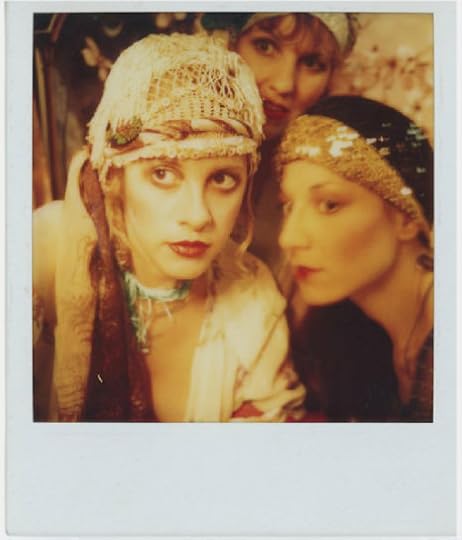

"Some people don’t sleep at night - I am one of those people. These pictures were taken long after everyone had gone to bed - I would begin after midnight and go until 4 or 5 in the morning. I stopped at sunrise - like a vampire… I never really thought anyone would ever see these pictures, they went into shoeboxes, where they remained. I did everything - I was the stylist, the makeup artist, the furniture mover, the lighting director. It was my joy - I was the model…" Stevie Nicks

Stevie Nicks Polaroid Selfies c.1976