Geof Huth's Blog, page 44

December 25, 2010

Solstice on the Seventh Christmas

This is the seventh year in a row that I've celebrated Christmas here at dbqp with a look at a piece of work by Jack Kimball. Every Christmas at dbqp has done the same, for it is a tradition at this blog, even in the waning days of blogdom, and a tradition I don't want to lose.

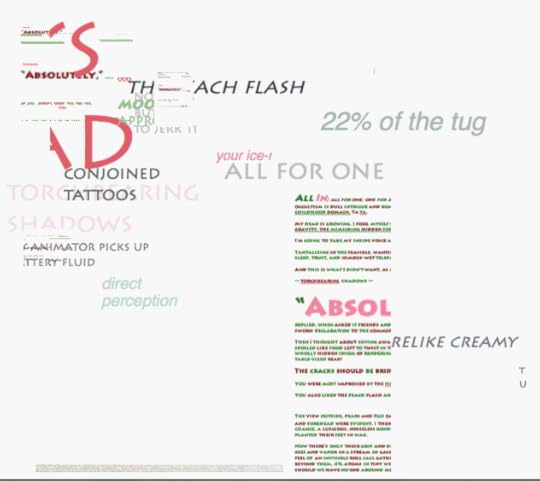

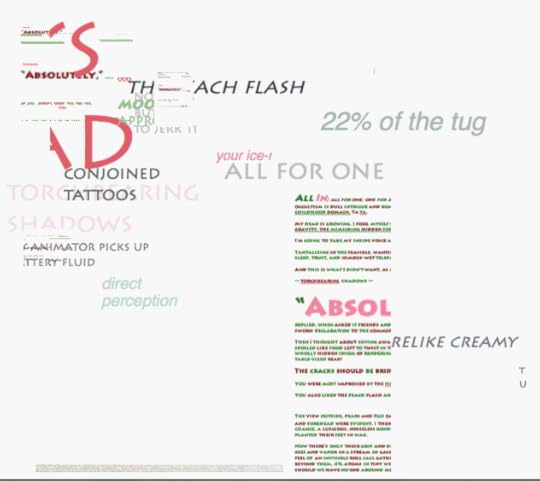

Jack Kimball, "Happy Solstice from Jack Kimball" (December 2010)Jack tells me that this is not a Christmas poem, even though (or, possibly, because) he knew I'd be posting it on Christmas day. In a note, he told me, "This is an attempt to exercise within while exorcising purely Xmas imagery. It's Solstice first and last."

Jack Kimball, "Happy Solstice from Jack Kimball" (December 2010)Jack tells me that this is not a Christmas poem, even though (or, possibly, because) he knew I'd be posting it on Christmas day. In a note, he told me, "This is an attempt to exercise within while exorcising purely Xmas imagery. It's Solstice first and last."

So what we have here is a solstice poem, but not one made because Jack's druidical or pagan tendencies. Instead, this poem is a response to Christmas, not so much a solstice celebration as an anti-Christmas celebration. An attempt to erase the commercialism of this time of year, an attempt to look outside to watch the snow come, but not really, because this is only incidentally a poem about the season of the year.

Instead, the poem is one about our lives, about the contemporary world and its inescapable enticements, about the chaos of our world of technology and human activity. It is about the assumed responsibilities we have within this culture, and it only glancingly refers to the weather outside (not yet frightful around here). But the poem refers to Christmas with hints of its commercialism and with its red and green letters. Things are not always what they seem to be or say they are, and in this piece Christmas is inescapable. It is like fighting a war against war: There is no hope it will disappear.

We are, in some ways, slipping into a new dark age. I've come to understand that this is not a new Age of Reason. The ability for politicians to argue political points has devolved into the assignment of epithets. Science is ignored in favor of faith, which is a manner of blind devotion. Even people I agree with, I find, argue not intellectually, but emotionally. And much of what feeds this fire of willful ignorance is a moneyed culture, and a culture of money, that desires a culture that does not question the development of obscene wealth for a few. Christmas is a symbol of this, about the valuing of riches over thinking, even more than it is the simple exchange of evidence of the simple fact of love, even more (of course) than it is the celebration of the birth of the Christ child, somehow one third of God in a seemingly monotheistic religion.

I, of course, celebrate Christmas but not as a Christian. I renounced Christianity in high school and saw no need to replace it with another impossible set of beliefs. I am not a spiritual man, nor a religious man. I am a realist. When it is winter, I do not require the arrayed mythologies of a culture frozen in place. Instead, I look for the reality of winter: the cold hard wind, short days and long nights, the sight and sifting and piling up of snow.

There is no snow here right now, though some may come tomorrow. So, in place of overseeing the accumuation of snow, and in my spare time from celebrating my friend mIEKAL aND's birthday, which is today, I spend a little time watching the swaths of text in Jack Kimball's little marquee poem slide back and forth, and up and down, never stopping, never even pausing, moving so much they the words are difficult to understand, but understanding that that is the world I live in.

Merry birthday, mIEKAL. Merry birthday, Jesus. And thanks for the presents. They were small in number but large in intent.

ecr. l'inf.

Jack Kimball, "Happy Solstice from Jack Kimball" (December 2010)Jack tells me that this is not a Christmas poem, even though (or, possibly, because) he knew I'd be posting it on Christmas day. In a note, he told me, "This is an attempt to exercise within while exorcising purely Xmas imagery. It's Solstice first and last."

Jack Kimball, "Happy Solstice from Jack Kimball" (December 2010)Jack tells me that this is not a Christmas poem, even though (or, possibly, because) he knew I'd be posting it on Christmas day. In a note, he told me, "This is an attempt to exercise within while exorcising purely Xmas imagery. It's Solstice first and last."So what we have here is a solstice poem, but not one made because Jack's druidical or pagan tendencies. Instead, this poem is a response to Christmas, not so much a solstice celebration as an anti-Christmas celebration. An attempt to erase the commercialism of this time of year, an attempt to look outside to watch the snow come, but not really, because this is only incidentally a poem about the season of the year.

Instead, the poem is one about our lives, about the contemporary world and its inescapable enticements, about the chaos of our world of technology and human activity. It is about the assumed responsibilities we have within this culture, and it only glancingly refers to the weather outside (not yet frightful around here). But the poem refers to Christmas with hints of its commercialism and with its red and green letters. Things are not always what they seem to be or say they are, and in this piece Christmas is inescapable. It is like fighting a war against war: There is no hope it will disappear.

We are, in some ways, slipping into a new dark age. I've come to understand that this is not a new Age of Reason. The ability for politicians to argue political points has devolved into the assignment of epithets. Science is ignored in favor of faith, which is a manner of blind devotion. Even people I agree with, I find, argue not intellectually, but emotionally. And much of what feeds this fire of willful ignorance is a moneyed culture, and a culture of money, that desires a culture that does not question the development of obscene wealth for a few. Christmas is a symbol of this, about the valuing of riches over thinking, even more than it is the simple exchange of evidence of the simple fact of love, even more (of course) than it is the celebration of the birth of the Christ child, somehow one third of God in a seemingly monotheistic religion.

I, of course, celebrate Christmas but not as a Christian. I renounced Christianity in high school and saw no need to replace it with another impossible set of beliefs. I am not a spiritual man, nor a religious man. I am a realist. When it is winter, I do not require the arrayed mythologies of a culture frozen in place. Instead, I look for the reality of winter: the cold hard wind, short days and long nights, the sight and sifting and piling up of snow.

There is no snow here right now, though some may come tomorrow. So, in place of overseeing the accumuation of snow, and in my spare time from celebrating my friend mIEKAL aND's birthday, which is today, I spend a little time watching the swaths of text in Jack Kimball's little marquee poem slide back and forth, and up and down, never stopping, never even pausing, moving so much they the words are difficult to understand, but understanding that that is the world I live in.

Merry birthday, mIEKAL. Merry birthday, Jesus. And thanks for the presents. They were small in number but large in intent.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on December 25, 2010 19:15

December 20, 2010

Looking at Writing without Looking

Karri Kokko Explains His "Writing Without Looking" from Geof Huth on Vimeo.

During a discussion over Skype from Helsinki, Finland, visual and other poet Karri Kokko explains his booklet "Writing without Looking," as he shows pages from the book to Geof Huth, who videotapes and comments from Schenectady, New York, on 20 December 2010 (21 December in Helsinki).

My friend Karri Kokko and I spoke tonight via Skype, and one of the topics we discussed was his "Writing without Looking" booklet, which is part of a larger project where Karri writes asemically without watching what he writes. During our discussion, but not this video, I wrote a couple of pieces in this manner myself, trying to learn what this kind of writing feels like. It is remarkably disconcerting.

This video contains no great discourse on this form of writing. It is simply the chatting of two friends, with Karri's distant voice a bit too quiet and my voice definitely too loud.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on December 20, 2010 20:07

December 19, 2010

December 16, 2010

Films Watched in November 2010

November was a big month for me, so far as the watching of films was concerned, but as I added missing data to this list tonight I noticed that I had forgotten to post the lists of films I've watched in the months of August, September, and October. I'll save those for later. I may actually end the year having watched 365 films, as planned, but it will be close, and I'm running out of time in more ways than I can count.

November 1, 2010

1. The Perfect Human (13 min, Jørgen Leth. 1967)

2. Trumbo (96 min, Peter Askin, 2007)

November 5, 2010

3. Not I (14 min, Neil Jordan, 2000)

4. Rough for Theatre I (17 min, Kieran J. Walsh, 2000)

5. Ohio Impromptu (11 min, Charles Sturridge, 2000)

6. Checking Beckett: Putting Beckett on Film (52 min, Pearse Lehane, 2003)

November 7, 2010

7. Waiting for Godot (120 min, Michael Lindsay-Hogg, 2000)

November 10, 2010

8. Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown (90 min, Pedro Almodovar, 1988)

November 14, 2010

9. You Can't Take it with You (126 min, Frank Capra, 1938)

November 15, 2010

10. The Running Man (100 min, Paul Michael Glaser, 1987)

November 17, 2010

11. Julien Donkey-Boy (94 min, Harmony Korine, 1999)

November 21, 2010

12. Alice in Wonderland (108 min, Tim Burton, 2010)

November 23, 2010

13. Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 1 (146 min, David Yates, 2010)

November 24, 2010

14. Robin Hood: Men in Tights (104 min, Mel Brooks, 1993)

November 25, 2010

15. Surrogates (88 min, Jonathan Mostow, 2009)

November 26, 2010

16. Jack and the Beanstalk (10 min, Edwin S. Porter, 1902)

17. Dream of a Rarebit Fiend (7 min, Edwin S. Porter, 1907)

18. The Thieving Hand (6 min, Vitagraph Company of America, 1908)

19. Impossible Convicts (3 min, G.W. "Billy" Bitzer, 1905)

20. When the Clouds Roll By (Food-Induced Nightmare Sequence, 8 min extract, Victor Fleming, 1919)

21. Beggar on Horseback (Dream Fantasy Wedding Sequence, 7 min extract, James Cruze, 1925)

22. The Fall of the House of Usher: A Film Version of Poe's Story (13 min, Melville Webber and J.S. Watson, Jr., 1926-1928)

23. The Love of Zero (15 min, Robert Florey and William Cameron Menzies, 1928)

24. The Tell-Tale Heart (24 min, Charles F. Klein, 1928)

25. Tomatos Another Day (7 min, James Sibley, Jr., and Alec Wilder, 1930)

26. Unreal News Reels Nos. 1 and 2 (6 min, Joseph Cornell, 1930s-1970)

27. The Children's Jury (9 min, attributed to Joseph Cornell, ca 1938)

28. Thimble Theater (6 min, Joseph Cornell, completed by Lawrence Jordan, ca 1930s-1970)

29. Carousel-Animal Opera (6 min, Joseph Cornell, completed by Lawrence Jordan, ca 1930s-1970)

30. Jack's Dream (4 min, Joseph Cornell, completed by Lawrence Jordan, ca 1930s-1970)

27 November 2010

31. Six Men Getting Sick (1 min, David Lynch, 1966)

32. The Alphabet (4 min, David Lynch, 1968)

33. The Grandmother (34 min, David Lynch, 1970)

34. The Amputee (5 min, David Lynch, 1974)

35. The Cowboy and the Frenchman (25 min, David Lynch, 1988)

36. Lumière (1 min, David Lynch, 1995)

37. Meshes of the Afternoon (14 min, Maya Deren and Alexander Hamid, 1943)

38. At Land (15 min, Maya Deren, 1944)

39. A Study in Choreography (4 min, Maya Deren, 1945)

40. Ritual in Transfigured Time (15 min, Maya Deren, 1946)

41. Meditation on Violence (12 min, Maya Deren, 1948)

42. The Very Eye of Night (15 min, Maya Deren, 1958)

43. Witch's Cradle (11 min, Maya Deren and Marcel Duchamp, 1943)

44. Bambi Meets Godzilla (2 min, Marv Newland, 1969)

45. Son of Bambi Meets Godzilla (2 min, Eric Fernandes, 1999)

46. The Imaginarium of Dr Parnassus (123 min, Terry Gilliam, 2009)

28 November 2010

47. The Bucket List (97 min, Rob Reiner, 2007)

48. The Runaway Jury (127 min, Gary Fleder, 2003)

49. The Rainmaker (135 min, Francis Ford Coppola, 1997)

50. Confessions of a Shopaholic (104 min, P.J. Hogan, 2009)

30 November 2010

51. Looney Lens: Anamorphic People (2 min, Al Brick, 1927)

52. Out of the Melting Pot (3 min, J. Ganz Studio, 1927)

53. H20 (3 min, Ralph Steiner, 1929)

54. Surf and Seaweed (13 min, Ralph Steiner 1929-30)

55. The Furies (3 min, Slavko Vorkapich, 1934)

56. Prohibition (4 min, Slavko Vorkapich, 1929)

57. Maytime (4 min, Slavko Vorkapich, 1937)

58. Light Rhythms (5 min, Francis Bruguière & Oswell Blakeston, 1930)

ecr. l'inf.

November 1, 2010

1. The Perfect Human (13 min, Jørgen Leth. 1967)

2. Trumbo (96 min, Peter Askin, 2007)

November 5, 2010

3. Not I (14 min, Neil Jordan, 2000)

4. Rough for Theatre I (17 min, Kieran J. Walsh, 2000)

5. Ohio Impromptu (11 min, Charles Sturridge, 2000)

6. Checking Beckett: Putting Beckett on Film (52 min, Pearse Lehane, 2003)

November 7, 2010

7. Waiting for Godot (120 min, Michael Lindsay-Hogg, 2000)

November 10, 2010

8. Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown (90 min, Pedro Almodovar, 1988)

November 14, 2010

9. You Can't Take it with You (126 min, Frank Capra, 1938)

November 15, 2010

10. The Running Man (100 min, Paul Michael Glaser, 1987)

November 17, 2010

11. Julien Donkey-Boy (94 min, Harmony Korine, 1999)

November 21, 2010

12. Alice in Wonderland (108 min, Tim Burton, 2010)

November 23, 2010

13. Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 1 (146 min, David Yates, 2010)

November 24, 2010

14. Robin Hood: Men in Tights (104 min, Mel Brooks, 1993)

November 25, 2010

15. Surrogates (88 min, Jonathan Mostow, 2009)

November 26, 2010

16. Jack and the Beanstalk (10 min, Edwin S. Porter, 1902)

17. Dream of a Rarebit Fiend (7 min, Edwin S. Porter, 1907)

18. The Thieving Hand (6 min, Vitagraph Company of America, 1908)

19. Impossible Convicts (3 min, G.W. "Billy" Bitzer, 1905)

20. When the Clouds Roll By (Food-Induced Nightmare Sequence, 8 min extract, Victor Fleming, 1919)

21. Beggar on Horseback (Dream Fantasy Wedding Sequence, 7 min extract, James Cruze, 1925)

22. The Fall of the House of Usher: A Film Version of Poe's Story (13 min, Melville Webber and J.S. Watson, Jr., 1926-1928)

23. The Love of Zero (15 min, Robert Florey and William Cameron Menzies, 1928)

24. The Tell-Tale Heart (24 min, Charles F. Klein, 1928)

25. Tomatos Another Day (7 min, James Sibley, Jr., and Alec Wilder, 1930)

26. Unreal News Reels Nos. 1 and 2 (6 min, Joseph Cornell, 1930s-1970)

27. The Children's Jury (9 min, attributed to Joseph Cornell, ca 1938)

28. Thimble Theater (6 min, Joseph Cornell, completed by Lawrence Jordan, ca 1930s-1970)

29. Carousel-Animal Opera (6 min, Joseph Cornell, completed by Lawrence Jordan, ca 1930s-1970)

30. Jack's Dream (4 min, Joseph Cornell, completed by Lawrence Jordan, ca 1930s-1970)

27 November 2010

31. Six Men Getting Sick (1 min, David Lynch, 1966)

32. The Alphabet (4 min, David Lynch, 1968)

33. The Grandmother (34 min, David Lynch, 1970)

34. The Amputee (5 min, David Lynch, 1974)

35. The Cowboy and the Frenchman (25 min, David Lynch, 1988)

36. Lumière (1 min, David Lynch, 1995)

37. Meshes of the Afternoon (14 min, Maya Deren and Alexander Hamid, 1943)

38. At Land (15 min, Maya Deren, 1944)

39. A Study in Choreography (4 min, Maya Deren, 1945)

40. Ritual in Transfigured Time (15 min, Maya Deren, 1946)

41. Meditation on Violence (12 min, Maya Deren, 1948)

42. The Very Eye of Night (15 min, Maya Deren, 1958)

43. Witch's Cradle (11 min, Maya Deren and Marcel Duchamp, 1943)

44. Bambi Meets Godzilla (2 min, Marv Newland, 1969)

45. Son of Bambi Meets Godzilla (2 min, Eric Fernandes, 1999)

46. The Imaginarium of Dr Parnassus (123 min, Terry Gilliam, 2009)

28 November 2010

47. The Bucket List (97 min, Rob Reiner, 2007)

48. The Runaway Jury (127 min, Gary Fleder, 2003)

49. The Rainmaker (135 min, Francis Ford Coppola, 1997)

50. Confessions of a Shopaholic (104 min, P.J. Hogan, 2009)

30 November 2010

51. Looney Lens: Anamorphic People (2 min, Al Brick, 1927)

52. Out of the Melting Pot (3 min, J. Ganz Studio, 1927)

53. H20 (3 min, Ralph Steiner, 1929)

54. Surf and Seaweed (13 min, Ralph Steiner 1929-30)

55. The Furies (3 min, Slavko Vorkapich, 1934)

56. Prohibition (4 min, Slavko Vorkapich, 1929)

57. Maytime (4 min, Slavko Vorkapich, 1937)

58. Light Rhythms (5 min, Francis Bruguière & Oswell Blakeston, 1930)

ecr. l'inf.

Published on December 16, 2010 20:59

December 15, 2010

Books Read in November 2010

November 2010 wasn't a bad month of reading, but most of these publications are quite short. I did read twenty-five publications this month, five short of my goal. I still may make 365 for the year, or one a day.]

November 1, 2010

1. Jones, Jonathan. thwart. the sticky pages press: Brussels, 2010.

November 5, 2010

2. Walser, Robert. Answer to an Inquiry. Translated by Paul North. Illustrated by Friese Undine. Ugly Duckling Presse: Brooklyn, 2010.

November 6, 2010

[Numbers 3 to 5 were read while waiting for a table in the lunch room of Harney & Sons in Millerton, New York.]

3. Gorey, Edward. The Eclectic Abecedarium. Pomegranate: San Francisco: 1983, 2008.

4. Gorey, Edward. The Utter Zoo and Alphabet. Pomegranate: San Francisco: 1967, 1995, 2010.

5. Gorey, Edward. The Sopping Thursday. Pomegranate: San Francisco: 1970, 1998.

November 7, 2010

6. Swensen, Cole. greensward. Ugly Duckling Press: Brooklyn, 2010.

7. 6 X 6 # 21: A Man Walks into a Bar. Fall 2010.

November 11, 2010

8. Agrafiotis, Demosthenes. Chinese Notebook. Translated from the Greek by John Sakkis and Angelos Sakkis. Ugly Duck Presse: Brooklyn, N.Y., 2010.

November 14, 2010

[Numbers 9 and 10 were purchased in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, in November 2010, and read almost immediately.]

9. Vicuña, Cecilia. Unravelling Words & the Weaving of Water. Translated by Eliot Weinberger and Suzanne Jill Levine. Graywolf Press: St Paul, Minn., 1992.

November 16, 2010

10. Perelman, Bob. Playing Bodies. With images by Francie Shaw. Granary Books: New York, 2003.

November 20, 2010

[Numbers 11 to 19 were read while visiting the recuperating Roy Arenella at his home in Greenwich, New York. I could see Robert Lax living there.]

11. Lax, Robert. The Love that Comes. Furthermore Press: Passumpsic, Vt., 1984.

12. Lax, Robert. A Poem for Thomas Merton. Journeyman Books: New York, 1969.

13. Lax, Robert. Just Mid Night. Furthermore Press: Davie, Fla., 1984.

14. Fisher, Roy and Ronald King. Scenes from the Alphabet. Circle Press Publications, 1978, 1984, 1996.

15. Lax, Robert. Thought. Journeyman Books: New York, 1966.

16. Lax, Robert. Clouds. Furthermore Press: Lyndonville, Vt., 1983.

17. Lax, Robert. Just Mid Night. Furthermore Press: Passumpsic, Vt., 1983.

18. Lax, Robert. At the Top of the Night. Furthermore Press: Passumpsic, Vt., 1983.

19. Lax, Robert. Arc. Furthermore Press: Passumpsic, Vt., 1984.

November 21, 2010

[Numbers 20 and 21 were purchased in Schuylerville, New York, just a little over the bridge from Greenwich, on the day I visited Roy, and I read them almost immediately.]

20. Palmer, Doug. Margaret's Experiences. OR: San Francisco, 1967.

21. Friefeld, Larry. The Importance of Swimming and Other Poems. Privately published: np, 1968.

[Chris Rizzo gave me number 22, a third edition of his little book of neologistic poems in Albany, New York, after a reading by Jay MillAr and other BookThug poets.]

22. Rizzo, Christopher. Naturalistless. Greying Ghost Press: Jamaica Plain, Mass., 2008.

[Number 23 is the smallest of the four publications Jack Crimmins sent me.]

23. Crimmins, Jack. Apricot: A Poem. Littoral Press: Oakland, Calif., 2007.

24. Gaze, Tim and Carol Stetser. A 'Soft Tissue'. Privately printed: Sedona, Ariz., 2010.

November 26, 2010

[Number 25 was my favorite book of the month. Essentially a collected poems of Picabia, it was a large and diverse book that took me, by far, the longest to read.]

25. Picabia, Francis. I Am a Beautiful Monster: Poetry, Prose, and Provocation. Translated by Marc Lowenthal. The MIT Press: Cambridge, Mass., 2007.

ecr. l'inf.

November 1, 2010

1. Jones, Jonathan. thwart. the sticky pages press: Brussels, 2010.

November 5, 2010

2. Walser, Robert. Answer to an Inquiry. Translated by Paul North. Illustrated by Friese Undine. Ugly Duckling Presse: Brooklyn, 2010.

November 6, 2010

[Numbers 3 to 5 were read while waiting for a table in the lunch room of Harney & Sons in Millerton, New York.]

3. Gorey, Edward. The Eclectic Abecedarium. Pomegranate: San Francisco: 1983, 2008.

4. Gorey, Edward. The Utter Zoo and Alphabet. Pomegranate: San Francisco: 1967, 1995, 2010.

5. Gorey, Edward. The Sopping Thursday. Pomegranate: San Francisco: 1970, 1998.

November 7, 2010

6. Swensen, Cole. greensward. Ugly Duckling Press: Brooklyn, 2010.

7. 6 X 6 # 21: A Man Walks into a Bar. Fall 2010.

November 11, 2010

8. Agrafiotis, Demosthenes. Chinese Notebook. Translated from the Greek by John Sakkis and Angelos Sakkis. Ugly Duck Presse: Brooklyn, N.Y., 2010.

November 14, 2010

[Numbers 9 and 10 were purchased in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, in November 2010, and read almost immediately.]

9. Vicuña, Cecilia. Unravelling Words & the Weaving of Water. Translated by Eliot Weinberger and Suzanne Jill Levine. Graywolf Press: St Paul, Minn., 1992.

November 16, 2010

10. Perelman, Bob. Playing Bodies. With images by Francie Shaw. Granary Books: New York, 2003.

November 20, 2010

[Numbers 11 to 19 were read while visiting the recuperating Roy Arenella at his home in Greenwich, New York. I could see Robert Lax living there.]

11. Lax, Robert. The Love that Comes. Furthermore Press: Passumpsic, Vt., 1984.

12. Lax, Robert. A Poem for Thomas Merton. Journeyman Books: New York, 1969.

13. Lax, Robert. Just Mid Night. Furthermore Press: Davie, Fla., 1984.

14. Fisher, Roy and Ronald King. Scenes from the Alphabet. Circle Press Publications, 1978, 1984, 1996.

15. Lax, Robert. Thought. Journeyman Books: New York, 1966.

16. Lax, Robert. Clouds. Furthermore Press: Lyndonville, Vt., 1983.

17. Lax, Robert. Just Mid Night. Furthermore Press: Passumpsic, Vt., 1983.

18. Lax, Robert. At the Top of the Night. Furthermore Press: Passumpsic, Vt., 1983.

19. Lax, Robert. Arc. Furthermore Press: Passumpsic, Vt., 1984.

November 21, 2010

[Numbers 20 and 21 were purchased in Schuylerville, New York, just a little over the bridge from Greenwich, on the day I visited Roy, and I read them almost immediately.]

20. Palmer, Doug. Margaret's Experiences. OR: San Francisco, 1967.

21. Friefeld, Larry. The Importance of Swimming and Other Poems. Privately published: np, 1968.

[Chris Rizzo gave me number 22, a third edition of his little book of neologistic poems in Albany, New York, after a reading by Jay MillAr and other BookThug poets.]

22. Rizzo, Christopher. Naturalistless. Greying Ghost Press: Jamaica Plain, Mass., 2008.

[Number 23 is the smallest of the four publications Jack Crimmins sent me.]

23. Crimmins, Jack. Apricot: A Poem. Littoral Press: Oakland, Calif., 2007.

24. Gaze, Tim and Carol Stetser. A 'Soft Tissue'. Privately printed: Sedona, Ariz., 2010.

November 26, 2010

[Number 25 was my favorite book of the month. Essentially a collected poems of Picabia, it was a large and diverse book that took me, by far, the longest to read.]

25. Picabia, Francis. I Am a Beautiful Monster: Poetry, Prose, and Provocation. Translated by Marc Lowenthal. The MIT Press: Cambridge, Mass., 2007.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on December 15, 2010 21:08

December 14, 2010

A Smaller Version of Me with a Head of Tissue Paper

Since writing is keeping me from writing.

Since writing is keeping me from writing.Since writing elsewhere is keeping me from writing here.

I realized tonight that I should point to a tiny piece of personal writing available elsewhere.

Nothing much, just a little remembrance of that object in my life that is most meaningful to me.

In a way, a gifted object.

This micro-essay appears in a project called "Object Lessons," which the poet H.L. Hix runs on his website.

Harvey is himself of interest: a poet who grew up in Middle Tennessee with my best friend from college, David Daniel, who may actually still be the poetry editor of Ploughshares, but I won't take the time to verify that at the moment.

Harvey has sent me a few of his books (and I'm sending him a stack of mine), and I'm surprised by one fact the most: all the translations he's done from Estonian.

Every language is a language made for poetry and capable of nothing more than making a poetry unique to that language.

Every event in a life is an event that could inhabit a poem.

I should make a poem sometime soon, but I've too much writing to do.

And maybe I don't have the right language for it.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on December 14, 2010 20:45

December 13, 2010

Twenty-One Words Can Be a Book

I had planned tonight to write a few words about the work of Stephen Nelson and to say a few words about the importance of paper, how a specific presentation of a poem, even one only moderately visual, can lead to an experience deep and more resonant than some of the many web-based experiences we have with words. And I say this as a writer primarily for the screen.

I had planned tonight to write a few words about the work of Stephen Nelson and to say a few words about the importance of paper, how a specific presentation of a poem, even one only moderately visual, can lead to an experience deep and more resonant than some of the many web-based experiences we have with words. And I say this as a writer primarily for the screen.But my night escaped from me. I lived through a wonderful dinner party, with carefully prepared and delicious food (I am a man of the senses), and filled with conversation both humorous and provocative, and not necessarily in a sensual way (I am a man of the mind), so by the time I made it back to the house lit by little Christmas lights in each of its windows the night was late, probably too late to write enough about Stephen's two books of poetry.

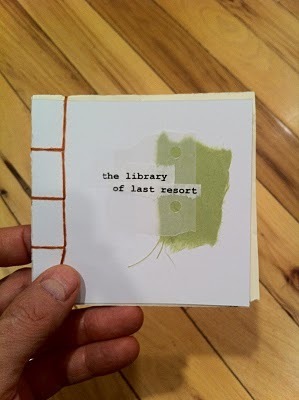

So I opted to write about a tiny book of poetry by Jonathan Jones, one that arrived here only today and one that demonstrates the importance of paper and how a specific presentation can lead to an experience deep and more resonant than some of the many web-based experiences we have with words. And this is a book and a poem that needs this presentation because it part of the writing. The two are inseparable. The words can be reproduced alone, but the words alone are not the poem.

And the book is called the library of last resort, which gives us a hint that this is a poem about the importance of the paper book, words on paper, the physical act of reading.

The book is a tiny handmade paperback released in a severely limited edition (I have number 3 of 6). It is sewn together by hand, includes at least four different kinds of paper and includes tape (an archival no-no of severe gravity), tears, and wrinkles all of which seem to be integral to the text.

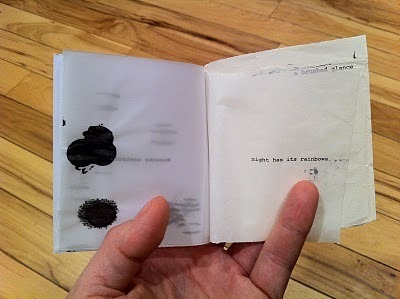

The book opens with two sheets of abstract markings on paper vellum (a gauzily transparent medium, that allows text and markings beneath these pages to glow through them). The third sheet of vellum provides the first line of actual text:

museums control the airThis is a quizzical statement, but not quite opaque. Museums are entities that preserve and display objects, institutions that assume that artifacts give evidence of and thus give meaning to our lives. Museums are about physical objects, not about the air, which cannot be controlled or stored in any real way. But if museums don't do their work, if the world becomes totally virtual, then all that would be left for museums would be the air around us, vague, impermanent, always changing.

One page of two ink blots on vellum intervenes and then the next line of the poem appears.

night has its rainbowsEverything seems to have its way of being, so night cannot have its rainbows, but poetry and the imagination allow for more possibility, including the possibility of metaphor. There may be many kinds of nights and many kinds of rainbows, enough so that there is some night that can have rainbows, and maybe (just) the physical object of a book can be one of these nights, one reliquary for these phantoms of light.

Then the next page is a wrinkled and taped sheet of simple office bond, with a single phrase, surrounded by the slight dirtiness of toner:

a brushed glanceMaybe a quick glance, just a quick once-over. Or, possibly, the brush as writing or painting instrument, and the writing of a phrase on a page in such a way that we glance over its brief physical self, stuck in the upper right-hand corner, and find something remarkable in its tiny meaningfulness.

The next sheet (not page, for every piece of this poem appears on the recto of a sheet of paper; the verso is always left blank, but not always blank) is almost a tissue paper and includes two words:

abstract zeroIt seems to me that zero is always abstract because it is impossible to identify nothing, but here (it seems to me) this phrase means that a poem can move us to a point of understanding zero, and the emptiness and fullness of zeroness. Or the opposite: that we need to avoid this zero.

Then a sheet of vellum saying,

the human integralwhich brings us back to numbers, suggesting that the human is the real thing (an integer), that the human is integral to art and poetry and life, and hinting (it seems to me) that the human is connected to the concrete over the virtual. And this point seems solidified by the next and last sheet:

Vellum, with three rows of four fingerprints, evidence of the human and the physical, and using a number that suggests some completeness (12 as a basic counting block of our lives), but one that is a little bigger than the human (ten, as in the number of ones fingers or toes, discounting the possibility of polydactyly for the moment). That the poem, the physical poem, can be just a bit bigger than the human, something bigger than us its creators.

And that's the whole poem, read through tonight, an entire book read, consumed, processed, interpreted, and presented out into the night because I couldn't hold it in.

_____

[Jones], Jonathan. the library of last resort. the sticky pages press: [Brussels], 2010.

Published on December 13, 2010 20:59

December 11, 2010

A Book for Our Age

John Bloomberg-Rissman's

Flux, Clot & Froth

is a modern-day epic, which is to say that it contains no adventures, no treks, no quests, yet mirrors the world it comes out of and all of its desires, and is huge in the way that an epic should be: inches thick when printed as a codex. The book is a memory of reading, a memory of a single synchronic slice of a civilization run through the consciousness of one poet. John has harvested whatever sequences of words interested him and he has melded these into a single frame, a giant canvas, its mirrored surface hidden from us by the deftness with which he has woven these various and dischordant texts into a single song, as if from a single source, in much the same way that a river is enriched by the tributaries feeding into it even if it seems but a single rolling force of water to our blindered eyes.

John Bloomberg-Rissman's

Flux, Clot & Froth

is a modern-day epic, which is to say that it contains no adventures, no treks, no quests, yet mirrors the world it comes out of and all of its desires, and is huge in the way that an epic should be: inches thick when printed as a codex. The book is a memory of reading, a memory of a single synchronic slice of a civilization run through the consciousness of one poet. John has harvested whatever sequences of words interested him and he has melded these into a single frame, a giant canvas, its mirrored surface hidden from us by the deftness with which he has woven these various and dischordant texts into a single song, as if from a single source, in much the same way that a river is enriched by the tributaries feeding into it even if it seems but a single rolling force of water to our blindered eyes.There is something hypnotic about this text to me, about the way that it fades in and out of focus, or from one focus to another, and always seeming to just one voice, his voice, though in various states and moods, coming at all. When I dip into it, I run over fifty pages at a clip wondering how I'd made it so far, and losing grip of the story, because there is none, because there are many, because I cannot hold onto the richness of the thing, how it is bigger and brighter than all of us, and eager to exceed our grasp.

So when John asked me to design the cover of his book, I did, though slowly, and awkwardly, making more errors in the construction of this cover than in almost anything I've ever made. (And error is a cornerstone of my poetics.) In the end, I'd devised a cover where the title is almost totally obscured, as is the author's name, a cover where the text is inscrutable in many ways: thrown into brambly piles of characters, obscuring the few recognizable forms, using almost nothing but letters that don't exist, a little rongorongo for the eye. You have to read the spine for the title, since the front cover is nothing but a reproduction of my feeling reading the book.

But this poem of John's is more than the poem itself. It is also a system of recording the sources of all the texts John has snatched from the river of words he read during its construction, and that system is both ingenious and beautiful. At the bottom of every page of the poem, in light-grey is the sequence of endnotes covered by that page. And if you buy volume 2 of the book, you will have the apparatus and be able to find all the sources of the poem, as well as nice little extras, like another poem. Volume 2 would be the essential disc of extras of this movie if this book were a movie, which it almost is. In this volume, you'll find an explanation of all the sources as well as the means to return to that place in the poem where any source is used. I used this to see how the words John appropriated from me were used in his text, and I was proud every time I saw what he'd done with my words.

Flux, Clot & Froth is a challenging book, but a rewarding one, a beautiful, an incantatory one. I sing its pages through my fingers to my eyes as I sleep.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on December 11, 2010 20:31