Twenty-One Words Can Be a Book

I had planned tonight to write a few words about the work of Stephen Nelson and to say a few words about the importance of paper, how a specific presentation of a poem, even one only moderately visual, can lead to an experience deep and more resonant than some of the many web-based experiences we have with words. And I say this as a writer primarily for the screen.

I had planned tonight to write a few words about the work of Stephen Nelson and to say a few words about the importance of paper, how a specific presentation of a poem, even one only moderately visual, can lead to an experience deep and more resonant than some of the many web-based experiences we have with words. And I say this as a writer primarily for the screen.But my night escaped from me. I lived through a wonderful dinner party, with carefully prepared and delicious food (I am a man of the senses), and filled with conversation both humorous and provocative, and not necessarily in a sensual way (I am a man of the mind), so by the time I made it back to the house lit by little Christmas lights in each of its windows the night was late, probably too late to write enough about Stephen's two books of poetry.

So I opted to write about a tiny book of poetry by Jonathan Jones, one that arrived here only today and one that demonstrates the importance of paper and how a specific presentation can lead to an experience deep and more resonant than some of the many web-based experiences we have with words. And this is a book and a poem that needs this presentation because it part of the writing. The two are inseparable. The words can be reproduced alone, but the words alone are not the poem.

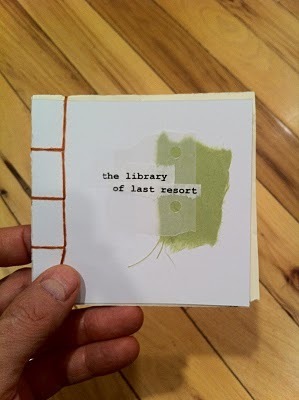

And the book is called the library of last resort, which gives us a hint that this is a poem about the importance of the paper book, words on paper, the physical act of reading.

The book is a tiny handmade paperback released in a severely limited edition (I have number 3 of 6). It is sewn together by hand, includes at least four different kinds of paper and includes tape (an archival no-no of severe gravity), tears, and wrinkles all of which seem to be integral to the text.

The book opens with two sheets of abstract markings on paper vellum (a gauzily transparent medium, that allows text and markings beneath these pages to glow through them). The third sheet of vellum provides the first line of actual text:

museums control the airThis is a quizzical statement, but not quite opaque. Museums are entities that preserve and display objects, institutions that assume that artifacts give evidence of and thus give meaning to our lives. Museums are about physical objects, not about the air, which cannot be controlled or stored in any real way. But if museums don't do their work, if the world becomes totally virtual, then all that would be left for museums would be the air around us, vague, impermanent, always changing.

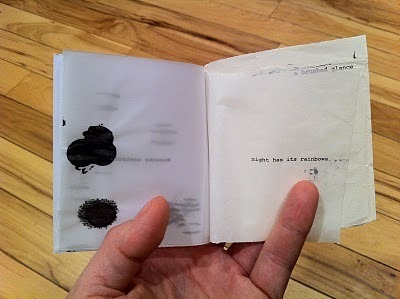

One page of two ink blots on vellum intervenes and then the next line of the poem appears.

night has its rainbowsEverything seems to have its way of being, so night cannot have its rainbows, but poetry and the imagination allow for more possibility, including the possibility of metaphor. There may be many kinds of nights and many kinds of rainbows, enough so that there is some night that can have rainbows, and maybe (just) the physical object of a book can be one of these nights, one reliquary for these phantoms of light.

Then the next page is a wrinkled and taped sheet of simple office bond, with a single phrase, surrounded by the slight dirtiness of toner:

a brushed glanceMaybe a quick glance, just a quick once-over. Or, possibly, the brush as writing or painting instrument, and the writing of a phrase on a page in such a way that we glance over its brief physical self, stuck in the upper right-hand corner, and find something remarkable in its tiny meaningfulness.

The next sheet (not page, for every piece of this poem appears on the recto of a sheet of paper; the verso is always left blank, but not always blank) is almost a tissue paper and includes two words:

abstract zeroIt seems to me that zero is always abstract because it is impossible to identify nothing, but here (it seems to me) this phrase means that a poem can move us to a point of understanding zero, and the emptiness and fullness of zeroness. Or the opposite: that we need to avoid this zero.

Then a sheet of vellum saying,

the human integralwhich brings us back to numbers, suggesting that the human is the real thing (an integer), that the human is integral to art and poetry and life, and hinting (it seems to me) that the human is connected to the concrete over the virtual. And this point seems solidified by the next and last sheet:

Vellum, with three rows of four fingerprints, evidence of the human and the physical, and using a number that suggests some completeness (12 as a basic counting block of our lives), but one that is a little bigger than the human (ten, as in the number of ones fingers or toes, discounting the possibility of polydactyly for the moment). That the poem, the physical poem, can be just a bit bigger than the human, something bigger than us its creators.

And that's the whole poem, read through tonight, an entire book read, consumed, processed, interpreted, and presented out into the night because I couldn't hold it in.

_____

[Jones], Jonathan. the library of last resort. the sticky pages press: [Brussels], 2010.

Published on December 13, 2010 20:59

No comments have been added yet.