Geof Huth's Blog, page 41

January 12, 2011

water(words

, it is the complexity of the simple that holds us in place. Only in the face of beauty do we stop. Otherwise, we move, always moving past everything. Beauty is a transformation, as when ink is written into letters of the air with a calligraphic brush, which is what Shinichi Maruyama does: writes sculptures of ink and water into the air.

, it is the complexity of the simple that holds us in place. Only in the face of beauty do we stop. Otherwise, we move, always moving past everything. Beauty is a transformation, as when ink is written into letters of the air with a calligraphic brush, which is what Shinichi Maruyama does: writes sculptures of ink and water into the air.Water Sculpture from Shinichi Maruyama on Vimeo.

Art work by Shinichi Maruyama

Composited by Tetsushi Wakasugi

Part of their beauty is their movement, captured in extreme slow motion: how a blade of water holds together and simultaneously pulls itself apart, letting droplets escape from the edge.

Part of their beauty is their stasis: frozen in place, these pieces suggest letters, seem more like manifestations of the phonemes released by a voice, more like true language (which is of the air) than print. These are kinetic pieces of asemic writing, and they stops only by the snapping of a camera or the halting of gravity.

The letter c rests above, as watery as an ocean but seemingly made of light.

(This sculptor found today on NPR by Nancy.)

ecr. l'inf.

Published on January 12, 2011 20:10

January 11, 2011

Tax, Taxation, Taxonomy

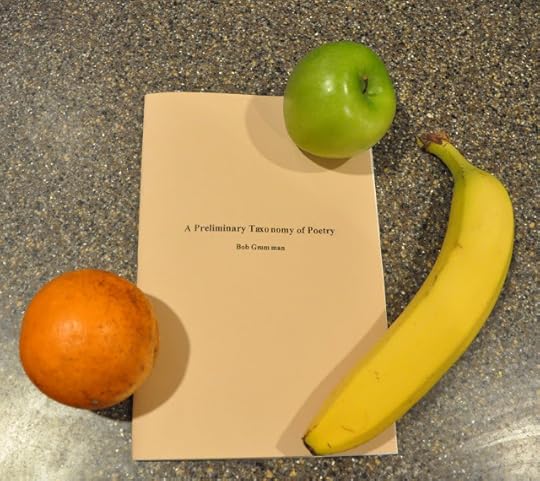

An Apple, an Orange, a Banana and Bob Grumman's A Preliminary Taxonomy of Poetry (2010)Bob Grumman has released a new book, really a chapbook, entitled A Preliminary Taxonomy of Poetry, and it combines the two halves of Bob's intellect into one. The first of these is an interest in clear thinking, in making distinctions even if only for distinction's sake, an interest in definition and categorization. And the second is its opposite, though it is the second that Bob rarely sees. The second is a tendency to simplify distinctions by setting rules that are not in evidence in the facts, a tendency to muddle things a bit, to wander.

An Apple, an Orange, a Banana and Bob Grumman's A Preliminary Taxonomy of Poetry (2010)Bob Grumman has released a new book, really a chapbook, entitled A Preliminary Taxonomy of Poetry, and it combines the two halves of Bob's intellect into one. The first of these is an interest in clear thinking, in making distinctions even if only for distinction's sake, an interest in definition and categorization. And the second is its opposite, though it is the second that Bob rarely sees. The second is a tendency to simplify distinctions by setting rules that are not in evidence in the facts, a tendency to muddle things a bit, to wander.And I love both these halves of Bob, even though, or probably because, they both can annoy me and enchant me, because their annoyance is often a possibility for illumination and because their enchantments lead me terribly astray. These two halves of Bob are the two halves of his visual poetry as well. He creates some of the most considered visual poetry, a poetry interested in the word and new senses of syntax, and he sometimes creates with this intellect visual poems that seem to care little about their visual presentation. Then he will create visual poems almost totally inscrutable from a verbal point of view but which are still among the most beautiful visual poems around. His best work is among my favorite being created these days.

So there's the context for this, a little accounting of my point of view, which might be only an accumulation of my own biases. I've left a few things out. I've known Bob for just under 25 years. He is my oldest visual poetry friend. And we almost never agree on anything. We come to visual poetry with much different ideas. As a matter of fact, when Bob says "visual poetry" he means something considerably narrower than I mean when using the same term. We are not sympatico in that way.

Why Taxonomy?

Bob opens the booklet with "A Defense of the Taxonomization of Poetry," which is an impassioned defense for taxonomies and the effort it takes to produce them. Part of the reason for his passion is that Bob has suffered through a few sometimes heated arguments over the years from poets, especially visual poets, who are themselves passionate in their opposition to taxonomies. These people see a taxonomy as the equivalent of an autopsy that produces no results. In this opening section, Bob does a reasonable, though quick, job of directly disputing the ideas of the critics of taxonomy, but he provides only no justification for taxonomy at all, except to say that "an effective taxonomy" allows "the clarification of discussion."

This is a big weakness to me. In the face of enormous criticism of taxonomy, Bob undermines the arguments of his opponents, but not in a way that argues the case for his own. All of his arguments are negative. None are positive. The one above is actually my reversal of his refutation of his detractors. Bob needs to prove how his taxonomies do something valuable. What he does is insist that they do something value without clarifying that values or giving any evidence of it.

Upper Levels of the Taxonomy

This taxonomy of Bob's is the most formal he's ever created. It begins with the Universe of the taxonomy (in this case "Matter"), and narrows down from there:

Domain: LifeImmediately, I'm thrown into a quandary, one of definitional confusion and doubt. Is Poetry really divided into Matter (instead of its opposing universe: Mind) or into Life (instead of Non-Life). Even if stored inside a human, aren't poems really only inanimate? and are they not more things of the mind rather than of matter? A poem on a page is not so much the poem as a poem accepted into a mind. This is a serious issue, one that needs justification in the taxonomy.*

Kingdom: Human Life

Phylum: Mentascendancy ("the pursuit of meaningfulness")

Class: Art

Order: Literature

Family: Poetry

At the Level of Prose and Poetry

Bob divides all literature into two main families, Poetry and Prose, and this might be a satisfactory division, though I would have, at least, discussed dramatic works and addressed the question of apparent hybrid forms, such as the verse novel and verse play. Here, Bob posits that "poetry is intended to be read slowly, read into rather than through: connotations, sounds, rhythms, flesh being emphasize rather than denotation only." In general, the general direction of this definition is fine, but it's too absolute and doesn't take into account such facts as the inclusion of doggerel in the family of poetry, or that fact that many prose works depend on all the effects mentioned by Bob and also do not depend on denotation alone. This definition is complicated by Bob's paragraph that consists of this sentence: "Literary prose is simply literature that is not poetry," which seems to assume that any works that depend on denotation alone (or, let's say, principally) are thus prose. This situation is quickly complicated again by Bob's not-quite-stated-but-clearly-implied point that poetry is text that includes flow-breaks, the most well known of which is the linebreak. Whatever poetry or prose is or isn't isn't clarified here.

Flow-Breaks

Bob, next discusses, flowbreaks (I'm discarding the hyphen): 1. the linebreak, 2. variable indentation, 3. interior line-gap (which is simply a caesura), and 4. the intrasyllabic linebreak. Here is the genius of Bob Grumman. He sees and defines topographic features of poetry that others have virtually ignored and he sees how they fit together into one set of poetic tools. My only problem with this is that one of his examples of an intra-syllabic linebreak is really intersyllabic, and the the fact that a line breaks within a word or a syllable doesn't make it significantly different from a traditional linebreak. What he should have used as his fourth category of a flowbreak was an instance of visual tmesis, which would be a different form of flowbreak.

Types of Poetry

This lengthy discussion has brought us only to the saddle-stapled middle of the chapbook, which is where Bob divides poetry into three classes: linguiexclusive poetry (poetry dependent on words alone) and pluraesthetic poetry (poetry that mixes "expressive modalities," such as the verbal and the visual. This distinction is solid, though I have questions with the subsubtypes of poetry Bob identifies.

Linguiexclusive Poetry

Bob divides linguiexclusive poetry into three subsubtypes: orthological, xenological, and language. The first is fairly standard poetry (subdivided yet again into categories), the second is poetry that breaks with the conventions of normal sense and syntax in various ways, and the third subsubtype is both confusing and unnecessary. All of its pieces should appear under xenological. Bob has divided to use a term here ("language poetry") that already has a meaning, though a taxonomically unhelpful one, and he gives it a new sense to no particular purpose.

The definition he gives is "Language poetry is poetry in words [that?] seem to be used with almost maximum communicational responsibility. Language is at the center of such poetry, not semantics or sound." This definition does not seem at all helpful to me, and I cannot imagine a poetry without semantics that still focuses on language.

Pluraesthetic Poetry

In discussing the types of pluraesthetic poetry, I'll skip any discussion of the fact that Bob redefines "visual poetry" for his own uses, because it is important for him to do it here in order for "visual poetry" to fit neatly into his definition of poetry. Bob, however, also distinguishes mathematical poetry and flowchart poetry ("poetry that uses the symbols of computers or other flow-charting in significantly expressive ways") from visual poetry, but I do not. Mathematical poems add mathematical features that visualize the poetry, so I consider them visual poems, and to have a category for flowchart poetry assumes that process symbols are textual and thus not visual. I'd argue, again, that they are not orthodox text, so these poems are also visual poems.

Also, Bob's definition remains indefensible: "poetry that uses mathematical symbols that actually carry out mathematical operations." These mathematical operations are not actual; they are apparent. That is a big different. Duck cannot be divided by yellow in any mathematical way, though it could in a metaphoric way that has nothing to do with math directly.

For reasons I don't understand, Bob distinguishes between "cyber poetry" and "hypertextual poetry," which is not a distinction. Hypertext poetry would be a subset of cyberpoetry. But the real taxonomic distinctions in the category would be between non-interactive and interactive digital poetries, not by the types of computer languages used in the coding of the poems.

Bob leaves out of his poetry videopoetry, which might have some overlap with cyberpoetry that Bob will have to work out.

Numbering

Finally, since Bob is presenting a complex nested taxonomy, he should design a numbering system that allows the user to determine their level in the taxonomy and, thus, be able to identify relationships more easily. At points I was briefly confused because I did not understand what certain headings were subsets of. Even the traditional outlining system once taught in school to students drafting essays could work here, but I think, given the number of levels in play, something direct though a little more complex, such as the number system in the Historical Thesaurus of the Oxford English Dictionary, would work better.

Coda

Bob's "Final Comment" includes this unsupportable statement: "I think no members of any other vocation care less about what they do than poets." I'd say this is an unprovable statement, so it's opening "I think" saves it, but I also believe everything after those first two words is false. Poets, in my experience, care more about poetics than about poetry. They are more likely to read someone writing about poetry than to read the poetry. They prefer, for instance, blogs on poetics over blogs that reproduce poetry. Poets are thinking people, even when guided by the heart, the spleen, the bone. But sometimes that interest in how poetry works does not extend to an interest in categorization. A general interest is not equivalent to an interest in taxonomy.

At the end of this, I realize that I'd like to see the next draft of this book. I like the idea of seeing how poetry can fall into categories, though I'm sure those categories will dissolve into one another. And I'm happy that Bob has made this book and glad that he has. But he still needs to prove how these defined categories could help us think about poetry. I don't see it, even though I like the effort to make these categories and the entertainment of the results of that effort.

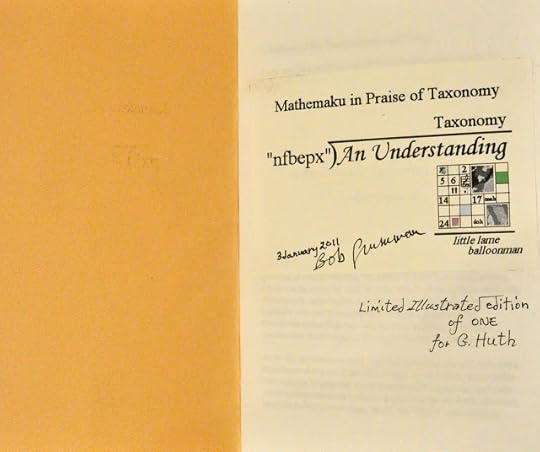

Finally, my thanks to Bob for giving me a special limited edition of one of the book, with a copy of one of his mathemaku pasted in. I've filled my copy with pencil marks of various kinds and notes to myself, but it is still a perfect copy. And I used pencil because I'm an archivist.

Bob Grumman's "Mathemaku in Praise of Taxonomy" Pasted into Geof Huth's Copy of APreliminary Taxonomy of Poetry

Bob Grumman's "Mathemaku in Praise of Taxonomy" Pasted into Geof Huth's Copy of APreliminary Taxonomy of Poetry_____

* Making such distinctions are part of my life. When working in archives and records management, one has to determine how to categorize records from non-records, as well as categorize records by type. Today, I demonstrated to a member of my staff why the State Police's collection of shells fired from every firearm placed for sale in New York State did not constitute records, but were instead a reference collection and, thus, non-records. I then explained that I could not determine if tissue blocks (tissue samples) kept by a government agencies were records or not without knowing the purpose for which they were created. My life is defined by making distinctions. It's part of my professional practice.

Grumman, Bob. A Preliminary Taxonomy of Poetry. The Runaway Spoon Press: Port Charlotte, Fla., 2010.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on January 11, 2011 18:45

January 10, 2011

If I Show, Will You Peep?

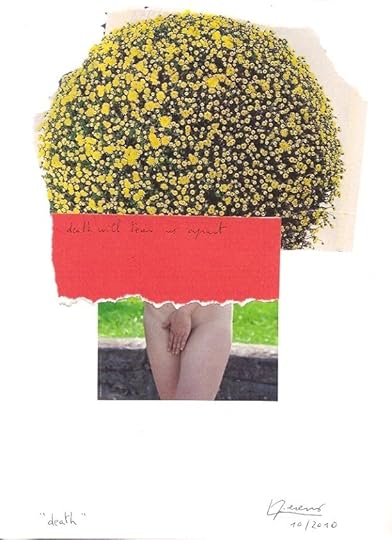

Luc Fierens, "death" (October 2010)

Luc Fierens, "death" (October 2010)This beautiful visual poem above by Luc Fierens is the first of many visual poems that will appear in the issue on International Visual Poetry in the online journal Peep/Show in the coming days. Peep/Show grows slowly over time into its full form, so return to its site until everything appears.

Subtitled "A Taxonomic Exercise in Textual and Visual Seriality," Peep/Show displays for us only sequences of work, and in the selection about to come, you'll see many ways to make visual poems and many kinds of sequences. The idea for this issue came from the editors, Anne Gorrick and Lynn Behrendt, who are constantly imaging new ways into the serial.

These two friends of mine asked me to curate the issue, which I did by asking ten visual poets over the globe to send in sequences of between seven and ten items. They chose the pieces, but I chose them. My confidence was in the poets. This issue is a selection of "International" visual poetry because it includes no North Americans. But there are poets here from South America, Europe, Australia, and Asia.

So you know what to look forward to, here are the visual poets, and their respective countries, arranged in alphabetical by first name.

Ayşegül Tozeren (Turkey)

Cia Rinne (Sweden, but living in Germany)

Helen White (United Kingdom, but living in Belgium)

Keiichi Nakamura (Japan)

Klaus Peter Dencker (Germany)

Luc Fierens (Belgium)

Marcelo Sahea (Brazil)

Satu Kaikkonen (Finland)

Suzan Sari (Turkey)

Tim Gaze (Australia)

Pay this issue some heed as it reveals itself. It is there for you to look at.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on January 10, 2011 19:23

January 8, 2011

In a Sense of Blue

Maggie Nelson, Bluets (2009)

Maggie Nelson, Bluets (2009)When I turned on this computer to write these words of blue, the computer screen, for just a second, opened to a field of blue, and it felt like blindness. A medium blue, it was not a sea always sculpting itself out of blue or receding from the shoreline in ever-darkening bands. It was a blank, a nothingness, the mind filled past suppression with what it couldn't take in over and over again.18. A warm afternoon in early spring, New York City. We went to the Chelsea Hotel to fuck. Afterward, from the window of our room, I watched a blue tarp on a roof across the way flap in the wind. You slept, so it was my secret. It was a smear of the quotidian, a bright blue flake amidst all the dank providence. It was the only time I came. It was essentially our lives. It was shaking.

Maggie Nelson, in her book Bluets , presents something else, something not just a wash of blue, though she is focused on blue in all its shades and connotations, and blue takes its vengeance out upon her, and we receive the glow that results. It is hard to say exactly what this book is. It is a sequence of 240 numbered paragraphs or sentences, prose, a fragmented personal essay, but clearly a poem, clearly poetic. It exists as small satellites of thought around the planet of blue. Some of the satellites orbit close to the idea of blue and others orbit at such a distance that they come within sight of that blue only briefly.

But everything comes out of blue, and blue guides the book. Insofar as thinking is never linear even when focused on a single topic, it is no surprise or disappointment that the book ranges over topics, starting with blue, but concerned with a lost love, with a friend who's become quadriplegic, with perception, with writing, with desire and sadness.

And this is a sad book, though one leavened with some insight gained over time, one enhanced by a sharp intellect, and a keen interest in searching not just for blue objects but also for blue facts, trivia about blue, connections between blue and everything it colors.

Bluets is a powerful work of art, a beautiful blue and glinting mosaic that seems to be many things at once and that is made out of many things as well. The book remains unromantic about romance, about love, lost or made, but it is filled with desire, desire for the color blue, desire for contact, desire for sex, and it is explicit in its details about sex, using (for instance) the term "making love" in place of the word "fuck" only once in 95 pages.

The issue of confessionalism never leaves the realm poetry, and it comes to us full force in this book. Maggie Nelson confesses her life to us, her loves, her sex, her genitals and those slipped into her, the terror and tenderness of caring for a physically crippled friend, her weeping, her emptiness at the empty explanations of her ex-lover. It is not her whole life or even a river leading out of that life, but it is a significant tendency, or set of tendencies, of her life. We learn, as we always must, that we cannot expunge the self without deleting the body, that even the most aloof of texts carries the self of the creator within it, for it remains an expression of that self. In this book, this expression is a wrenching revelation.42. Sitting in my office before teaching a class on prosody, trying not to think about you, about my having lost you. But how can it be? How can it be? Was I too blue for you. Was I too blue. I look down at my lecture notes: Heártbréak is a spondee. Then I lay my head down on the desk and start to weep. —Why doesn't this help?

This morning, up until 2 am reading this book and writing, I wrote a brief note to my friend Tom Beckett, who made me aware of this book, and this inarticulate sequence of sentences I sent him is probably all I can valuably say about this book:

As my poety friend Anne Gorrick says, "The best work leaves me the most inarticulate." So it is that I am inarticulate now.But I wasn't ready for it.

I ordered it. It arrived on a day that seems like today but was yesterday. I started reading it immediately.

I read slowly.

It is so painful to me. So beautiful. I'm not strong enough for a book like this.

I saw the film Shutter Island last night for the first time and learned that all of its tropes (its jittery editing, its saturated color, is echoing music, its ornate storytelling) served the final purposes of the film. Everything is of a piece, even if it is in pieces. But I was hit hardest during the credits when the final song began. It was a mix of two tunes, "This Bitter Earth" performed by Dinah Washington and Max Richter's "On the Nature of Daylight," a mashup and so an original work by Robbie Robertson, whose work as music supervisor for the film was astounding. The lyrics are almost nothing more than spoken for most of the song, but at times Washington's voice turns into a note of a bird's song and the violins come in in waves to and over the shore of her voice.

I purchased that song last night and listened to it as I wrote a poem to H.L. Hix and as I read Bluets, going back and forth between the two activities, because writing is just a version of reading. This spliced song, beautiful to the point of aching, became the soundtrack to this book, beautiful to the point of aching. Both when I stopped reading the book this early morning and when I finished reading the book later this morning, after a shortened slumber, I shook, my body shook. Maggie Nelson's words made me shake. Somehow, I'd become human through those words, which seems good enough praise to me.

The book is covered now by my penciled notations (underlines, brackets, check marks, words), and I was sure to make note of every quotation from Emerson, who always speaks to me. Everything is of a piece, even if it is in pieces.

_____239. I am writing all this down in blue ink, so as to remember that all words, not just some, are written in water.

Nelson, Maggie. Bluets. Wave Books: np, 2009.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on January 08, 2011 11:35