Geof Huth's Blog, page 31

April 6, 2011

Why We Keep Our Failures Close (A Fifty-Seventh Letter to a Young, Imaginary Visual Poet)

Delayed? Yes, that's the word. And, yes, once again.

But there are two kinds of delay, as I see it. One is procrastination or forgetting, the simple act of allowing something not to happen but for no reason beyond laziness, a lack of interest or will, a desire that doesn't fill a body with action. The other is a delay required by some fact of life, which could be a family tragedy or, simply, the need to complete other work.

The latter is my reason, but maybe it is the worse one. If so, I am sorry. There's something about making that pushes me to make, and usually the things I make are poems. Fortunately, I define "poem" quite broadly being uninterested in being held back because something is defined out of my range of activity, and I'd say you should do. Worrying about definition can be a useful effort, and knowing what you're doing or what to call what your doing can be something useful for an artist. But you don't need to be a critic. You don't need to know how your work falls within the streams of contemporary making, and its best not to worry about the significance of your work, because you'll never know. Someone will do that for you after your dead. If your lucky. For the unlucky many of us, that determination comes long before we die, and in the negative.

And I don't know why you should worry about your bad work, or even why you should hide it. Good work is always produced through the process of editing. You edit out the bad parts, you edit out the bad poems, and people in general edit out the bad careers. Some people argue, and I think it's good advice, that poets should show only their best work. This might give people the illusion that you produce at an exceptionally high quality all the time, but who could really believe that.

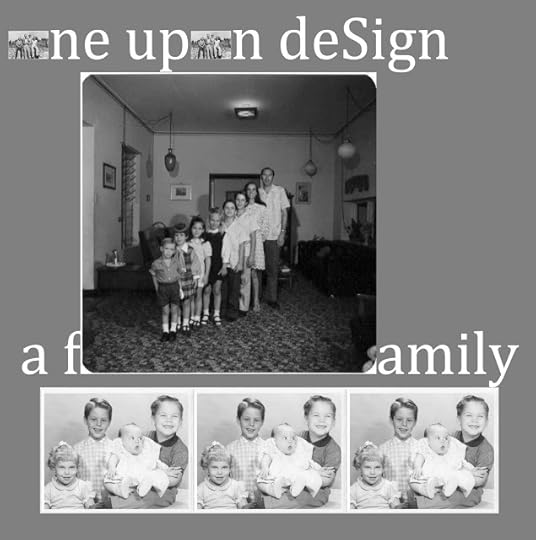

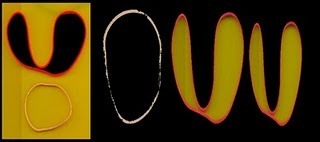

Take this old draft of a visual poem, actually the opening to a sequence that I never completed:

I don't think I've shown anyone this piece before, because it is such a mess. There is more wrong with it than right with it, because there's nothing right with it. My idea was to tell a vispoetic autobiography that used photographs from my family. And these photographs, of people who no longer exist though almost all are still alive, are all I still appreciate in this piece.

Although I tried to work an idea into something useful, I never did, but neither am I ashamed of this. I hate all my bad work--and I'm ironically good at producing it--but I keep them all. My poetics is one of production merely because production is the purest fact of creating, the inescapable necessity (meant in many ways), because production proves we're alive and creativity boils down only to the simple fact of our existence, evidence of that.

So I am not encouraging you to distribute all your bad work. I'm just saying don't be ashamed of it. Save it as evidence of the work your made yourself do. Each piece you create is evidence of some hardwon victory at creating something, evidence of something you learned, even if it was something you never want to do again. Don't try to publish each of these, but hold onto them. If nothing else, they can serve to control your vanity, which is something that all poets need, that all artists need.

Sometimes, we think we are special because we can make something others can't make. But vanity is a disease. It makes us complacent when we have to be resilient. And we become resilient by looking at our worst work every day.

So work on that, and save those deformed babies of yours. You won't find homes for them, but that is best for all of us.

ecr. l'inf.

But there are two kinds of delay, as I see it. One is procrastination or forgetting, the simple act of allowing something not to happen but for no reason beyond laziness, a lack of interest or will, a desire that doesn't fill a body with action. The other is a delay required by some fact of life, which could be a family tragedy or, simply, the need to complete other work.

The latter is my reason, but maybe it is the worse one. If so, I am sorry. There's something about making that pushes me to make, and usually the things I make are poems. Fortunately, I define "poem" quite broadly being uninterested in being held back because something is defined out of my range of activity, and I'd say you should do. Worrying about definition can be a useful effort, and knowing what you're doing or what to call what your doing can be something useful for an artist. But you don't need to be a critic. You don't need to know how your work falls within the streams of contemporary making, and its best not to worry about the significance of your work, because you'll never know. Someone will do that for you after your dead. If your lucky. For the unlucky many of us, that determination comes long before we die, and in the negative.

And I don't know why you should worry about your bad work, or even why you should hide it. Good work is always produced through the process of editing. You edit out the bad parts, you edit out the bad poems, and people in general edit out the bad careers. Some people argue, and I think it's good advice, that poets should show only their best work. This might give people the illusion that you produce at an exceptionally high quality all the time, but who could really believe that.

Take this old draft of a visual poem, actually the opening to a sequence that I never completed:

I don't think I've shown anyone this piece before, because it is such a mess. There is more wrong with it than right with it, because there's nothing right with it. My idea was to tell a vispoetic autobiography that used photographs from my family. And these photographs, of people who no longer exist though almost all are still alive, are all I still appreciate in this piece.

Although I tried to work an idea into something useful, I never did, but neither am I ashamed of this. I hate all my bad work--and I'm ironically good at producing it--but I keep them all. My poetics is one of production merely because production is the purest fact of creating, the inescapable necessity (meant in many ways), because production proves we're alive and creativity boils down only to the simple fact of our existence, evidence of that.

So I am not encouraging you to distribute all your bad work. I'm just saying don't be ashamed of it. Save it as evidence of the work your made yourself do. Each piece you create is evidence of some hardwon victory at creating something, evidence of something you learned, even if it was something you never want to do again. Don't try to publish each of these, but hold onto them. If nothing else, they can serve to control your vanity, which is something that all poets need, that all artists need.

Sometimes, we think we are special because we can make something others can't make. But vanity is a disease. It makes us complacent when we have to be resilient. And we become resilient by looking at our worst work every day.

So work on that, and save those deformed babies of yours. You won't find homes for them, but that is best for all of us.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on April 06, 2011 20:32

April 5, 2011

Reading Poetry and Paying for It

As people in the world of poetry know, the University of Chicago Press allows anyone to download one free e-book a month, though it is a book of its choosing. Since the press doesn't have to reproduce the book in any tactile form, these digital copies are reasonably cheap to distribute and represent only the loss of revenue, rather than the loss of revenue and the loss of the possibility of revenue that a hardcopy book represents. But why would the UCP release twelve books for free each month? Because, as it always is with gifts from a profit-making enterprise, because it is a way to make money. And today I learned just how this works.

Keeping in mind that I don't begrudge a press' making money, let me note up front that I spend plenty of money each year on books of poetry, or books somehow related to poetry. While working in the kitchen tonight, I thought to myself that I buy more books of poetry a year than most people buy books at all. And then I realized the ridiculousness of that thought. To compare my purchasing of books, which is rampant and undisciplined, which is evidence of my desire to drink the word (and the image of word) until the thought of drinking can no longer be made in my head--and that time never comes--with those of the general public is to assume there is some comparison that might be made. But there is not. Those of us like me are merely insane, insatiable when it comes to the written word. I've been enamored of that word since before I could read.

So I decided to download UCP's freely offered book of the month today: Charles' Bernstein's My Way. (I imagined, of course, Sid Vicious, though in the guise of Gary Oldman, singing a song.) The subtitle of the book is Speeches and Poems, which made me want to pull a copy down onto the hard drive of my computer. The idea there was alluring: the idea of the writer as everything about writing. Not just a poet, but a thinker, someone who could not, or would not, see the distinction between the poem based on theory and the theory from which the poem might flower. And in his preface to the book, in the first sentence even, Bernstein seems to make the point I'd wanted the book to make: "What is the difference between poetry and prose, verse and essays?" It's not even a statement. It's interrogative.

I couldn't just read the book, though. I had to download a free copy of Adobe Digital Editions first. This product appears to be an e-reader software for PDFs, and I could see Adobe's interest in developing such a product. It's its way of trying to control the market, to make the e-reader solutions bed PDF-based, which Adobe could then argue for on the basis that PDF is an open international standard. And the PDF is a good reading platform. It is one that can ensure the maintenance of the look and feel of a "real" book, but one that can still support digital text, text that can be copied out of a book and repurposed. Of course, there's no real need for the e-reader if that was one's only goal, because Adobe Reader, Adobe Acrobat, and any number of other PDF readers could allow a way to read the PDF I downloaded after downloading Adobe Digital Editions. This new product has one goal: DRM. Digital Rights Management. The control of UCP's intellectual property.

The reader also, I should add, provides a few other features not common in PDF software products: a left sidebar with the table of contents, a shelving area for your books, and the ability to bookmark pages. Otherwise, it's a regular PDF reader, just a little klugier. Let me make it clear that I read on a computer screen for hours a day, much more than I read in paper, which is sometimes also for hours a day.

But I found the process of reading this book remarkably uncomfortable. If I left the book as a two-page spread, I could not read the text comfortably. And flipping pages is PDFy. I wanted to swipe my mouse over the page to turn a page, but I could not. I had to use arrows, and the arrows on this interface are small and stuck in the corner. They work just as they do in Adobe Acrobat, but I find that unnatural. I want to hit a right arrow, so I can move to the right through the book, but I have to hit a down arrow (to move down into the book?). Anyway, when I enlarge the page to make the text readable, it becomes horribly pixelated, quite ugly, and I just could not read it. The text looks as if it has been PDF'd not from the original digital file, but from paper and then OCR'd. It was agony. I could read for about three minutes, and then I gave up.

And what did I do? I decided to buy Bernstein's Attack of the Difficult Poems, because social media (initiated by Bernstein himself) told me that this book was available for 30% off right now from UCP. And it was. Then I decided to get Girly Man, Bernstein's penultimate book of poems if my memory serves me, because I suddenly realized I'd never bought a copy, and this was also 30% off. So, finally, I decided to buy a copy of My Way. Three books for 30% off, so it's like getting one book for free. And that's how UCP made $56 from me today: by giving me a free book I could not read.

I didn't feel used. I was happy to have the books, though I have to wait for these to travel to me--I cannot read them immediately. But this process made me think about why the book might have been formatted as it was. As I fed my dogs in the basement, I thought about other e-readers I'd seen, and each of these simply let text flow over the screen, so text was totally digital, not held in place, not static. The text was set up so that one could enlarge the text and it would naturally fill the rectangle of the screen, not push out of that window the way Bernstein's book did. So I wonder if UCP decided on this method of presentation because it preserved the formatting of the poems in the book. No matter what form poems take on a page, they always make visual statements--even prose poems do. Visual form matters in poem, so if an e-reader merely allows text to grow and flow into and fill a screen the lines of a poem may be obscured and thus rendered useless.

So I wondered about a solution, and one came to me. E-readers should have two modes, which readers can toggle between during reading. One will present the paper-based formatting, which might be necessary for poems, photo books, and other more highly designed books. But the other mode has to be flowing text, because in the end reading the text is essential.

And then I thought: I have to read with on a booklike screen. I can't read on my landscape-oriented laptop. I need to read on a portrait-oriented device, or one that can be oriented in that way.

Otherwise, Charles Bernstein and the University of Chicago Press will get too rich.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on April 05, 2011 20:20

April 3, 2011

Books Read in March 2011

This has been a busy year, so I am way behind in my reading, having read about half the publications I'd planned to have read this year so far. Last month, I read a little bit more than I had so far, so there is at least some improvement.

March 5, 2011

1. Barwin, Gary. Four Panels. № Press: Calgary, February 2011.

2. Barwin, Gary. Six Panels. № Press: Calgary, January 2011.

March 6, 2011

3. Wahlgren, J. Michael. fr. Icebox. Pamphlet #13. Greying Ghost Press: np, [2010 or 2011].

4. Bernstein, Michael. Nanostars. Greying Ghost Press: np, [2010].

5. Behrendt, Lynn. This is the Story of Things that Happened. Dusie, np, 2011.

6. Behrendt, Lynn. Acquiescence. Dusie, np, 2011.

March 8, 2011

7. Kostelanetz, Richard. Minimal Erotic Fictions. C'est mon dada # 49. Redfoxpress: Achill Island, Ireland, 2010.

8. Helmes, Scott. Poems from Then to Now. C'est mon dada # 51. Redfoxpress: Achill Island, Ireland, 2010.

9. Agrafiotis, Demosthenes. Art X Art. C'est mon dada # 52. Redfoxpress: Achill Island, Ireland, 2011.

10. Stetser, Carol. Threads. C'est mon dada # 53. Redfoxpress: Achill Island, Ireland, 2011.

11. Boschi, Anna. Correspondence. C'est mon dada # 54. Redfoxpress: Achill Island, Ireland, 2011.

12. Nelson, Stephen. Flylyght. The Knives Forks and Spoons Press: Newton-le-Willows, Merseyside, U.K., 2011.

13. Nelson, Stephen. The Faithful City: Visual Poems. afterlight press: Hamilton, Lanarkshire, U.K., 2006.

March 15, 2011

14. Vassilakis, Nico. staring@poetics. Xexoxial Editions: La Farge, Wisc., 2011.

March 23, 2011

15. Armantrout, Rae. Money Shot. Wesleyan University Press: Middletown, Ct., 2011.

March 24, 2011

16. Yu, Julia. Goodnight, Dune. http://goodnightdune.com/. np: np, nd [read on 24 march 2011]

March 25, 2011

17. Howe, Susan. That This. New Directions: New York, 2010.

March 26, 2011

18. Malcontent 4, 1984.

19. Malcontent 10, 1985.

20. Malcontent 12, nd.

March 31, 2011

21. [Jones, Jonathan]. trees. the sticky pages press: Brussels, [2011].

ecr. l'inf.

March 5, 2011

1. Barwin, Gary. Four Panels. № Press: Calgary, February 2011.

2. Barwin, Gary. Six Panels. № Press: Calgary, January 2011.

March 6, 2011

3. Wahlgren, J. Michael. fr. Icebox. Pamphlet #13. Greying Ghost Press: np, [2010 or 2011].

4. Bernstein, Michael. Nanostars. Greying Ghost Press: np, [2010].

5. Behrendt, Lynn. This is the Story of Things that Happened. Dusie, np, 2011.

6. Behrendt, Lynn. Acquiescence. Dusie, np, 2011.

March 8, 2011

7. Kostelanetz, Richard. Minimal Erotic Fictions. C'est mon dada # 49. Redfoxpress: Achill Island, Ireland, 2010.

8. Helmes, Scott. Poems from Then to Now. C'est mon dada # 51. Redfoxpress: Achill Island, Ireland, 2010.

9. Agrafiotis, Demosthenes. Art X Art. C'est mon dada # 52. Redfoxpress: Achill Island, Ireland, 2011.

10. Stetser, Carol. Threads. C'est mon dada # 53. Redfoxpress: Achill Island, Ireland, 2011.

11. Boschi, Anna. Correspondence. C'est mon dada # 54. Redfoxpress: Achill Island, Ireland, 2011.

12. Nelson, Stephen. Flylyght. The Knives Forks and Spoons Press: Newton-le-Willows, Merseyside, U.K., 2011.

13. Nelson, Stephen. The Faithful City: Visual Poems. afterlight press: Hamilton, Lanarkshire, U.K., 2006.

March 15, 2011

14. Vassilakis, Nico. staring@poetics. Xexoxial Editions: La Farge, Wisc., 2011.

March 23, 2011

15. Armantrout, Rae. Money Shot. Wesleyan University Press: Middletown, Ct., 2011.

March 24, 2011

16. Yu, Julia. Goodnight, Dune. http://goodnightdune.com/. np: np, nd [read on 24 march 2011]

March 25, 2011

17. Howe, Susan. That This. New Directions: New York, 2010.

March 26, 2011

18. Malcontent 4, 1984.

19. Malcontent 10, 1985.

20. Malcontent 12, nd.

March 31, 2011

21. [Jones, Jonathan]. trees. the sticky pages press: Brussels, [2011].

ecr. l'inf.

Published on April 03, 2011 09:25

April 2, 2011

The Better Half of dbqp

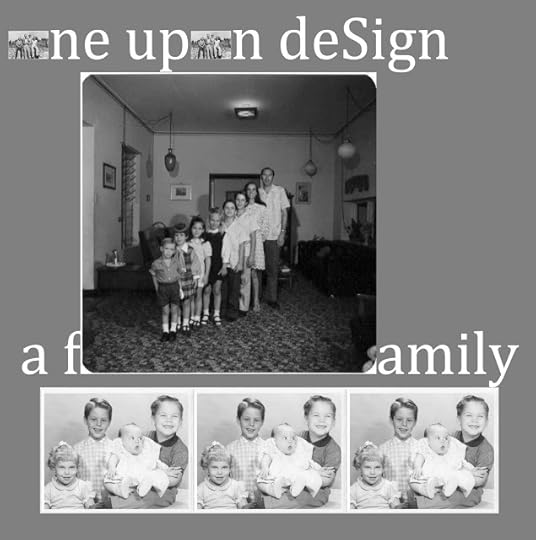

The Entire Print Run of derek beaulieu's "db" (dbqp # 234, 2 April 2011)

The Entire Print Run of derek beaulieu's "db" (dbqp # 234, 2 April 2011)In a newfound effort to revitalize my ancient and tiny micropress, I have finally published a duet of visual poems by derek beaulieu as a single broadside. These are two beautiful and asemic Letraset poems by one of the masters of contemporary visual poetry.

In some way, I see this publication, release in a very limited edition of 61, as a companion piece to derek's monumental "Prose of the Trans-Canada", which was just released by BookThug in an edition of 150 and a massive 16" x 52". (I've already purchased a copy and am now anxiously awaiting it, so I can pay whatever huge sum it will cost me to frame this piece, which itself costs Can$95, which I hate to inform my countrypeople is more than US$95, but well worth it for one of the masterpieces of today's visual poetry).

I'm selling derek's "db" (title by me) for US$2 postpaid, most of which cost will be my mailing costs. I'm open to trades, of course, and will merely be happy to get this work out in the world.

And I'm thinking of releasing a leaflet version sometime in the future too...

ecr. l'inf.

Published on April 02, 2011 18:02

April 1, 2011

In the Realm of Words and Vision

We see and, usually, think nothing of it. We are blind for most of our lives, for everything is invisible to us. We are both deaf and blind, and surrounded by mysteries we don't recognize. We pass through the world and see its bare outlines without recognizing the depth of it all, without moving our heads to just the right point so that we can see something that might change our lives. We don't realize we have to squat sometimes to see the world, or turn our heads or look down, or up. The world is a stew of sounds, yet we don't hear even the words spoken to us. We merely recognize their meanings as if no sounds were used to bring those meanings forth. We don't live. We merely exist. It all passes by us as if it didn't exist, so intent are we to get something (meaningless) done.

Then suddenly it changes, maybe only momentarily, and we are the kings and queens of the world because we can see what has been hiding before our eyes. For a second, only we know something beautiful. And we take it in. Then the car we are riding in proceeds forward, dumbly but dutifully, and we return to our lives, our existences, in the mute and formless world.

Maybe it is that poetry or maybe it is that the most we can extract from poetry or maybe it is that the best poetry can do for us is expose us to these heightened states of experience through the use of words. Poetry might be little more than a swift slap across the face, something to wake us out of our doldrums. And maybe it is that visual poetry does the same with the pieces of language, in their visible forms, and with images. And maybe it is that we know best how to live through our eyes.

Tonight, I'm thinking of my wife Nancy's (NF Huth's) newest chapbook, which arrived at the house today, and which is a simple piece of glory at the discovered mysteries of the world. This chapbook is part of the "this is visual poetry" chapbook series edited by Dan Waber, so it carries the title requires of every publication in that series: this is visual poetry. The series attempts to define the broad landscape of visual poetry by publishing a wide range of work from visual poets from across the globe.

And one of the many revelations from the series is that my wife is a visual poet. She comes at visual poetry from the world of the poet, from her poet's sensibilities, from a sense of the word and how it can say by being said and also by not being said. But she also comes at visual poetry as a photographer for she is always taking pictures, her eye is always seeing things I cannot see, and many of these are pictures that are both pointy and blue.

I barely noticed she was becoming a visual poet. She began by taking pictures, but these were all taken in the past. The vast majority of the pictures she took in 2009 at the Saari Residence in Mietoinen, Finland, but there are also pictures from Manchester (England, also 2009), and Caroga Lake and Schenectady in New York. These are simply pictures that caught her eye, and they are always still, motionless, photographs of objects for contemplation. No people appear in these photographs, no animals, no signs of movement, so no blurring, and they are made for us to see the world.

She began to sit on the couch over the winter and play with photographs on her iPad, and I had no idea what she was doing at first. Maybe she didn't either. She was distorting the photographs there, removing the details of contrast, flattening out variegations into solid bands of color, making the photographs more demandingly what they were objects of.

With the photographs carefully processed, with their colors regularized to soothing earth tones with surprising yet small areas of bright color, she began to place text upon these photographs. Very few words, but words suggesting a syntactic sequence. Words in colors to match the surroundings, and sometimes even to camouflage them, all done to force the reader to look, to slow down, to think. To see.

The words are simple and quiet and also uniform in certain ways. Each of these phrases—for each poem is made out of a single hollowed-out phrase—begins with a present participle (almost a gerund), ends with the pronoun "it," and somewhere within the phrase a word or words are missing. These pieces mean by saying and not saying, by leaving out, by leaving something unsaid, by making the reader write the poem. These are quiet, contemplative poems, and melancholy in spots. Yet fill the reader (speaking only for myself, the husband of the poet) with a sense of warmth, comfort, and this simmering joy at their beauty and deftness.

Spacing matters, too. She has placed the individual words in each phrase on the pages in such a way that we have to search for them and follow them, though they are not in a line. Take the cover poem, "seeing a place." The phrase begins top left with "seeing" sitting on the ceiling just above a wind. We move to the right and drop down, and there is an "a" in a corner where a window, a wall, and a ceiling meet. We drop down and move right and we see the word "place" on a wall between two windows, partially written on a curtain. Then there is a huge gap and we jump over a gap we must fill in before we reach "in" written in the bottom middle of a four-pane window. Chairs and windows are all around, and we are made to think of how this place is a holder of light and furniture and people, but also of words.

The words of the poem don't directly say anything, but they force thinking out of us. And they make us see, which is one of the best gifts a poem or a visual poem can be for us. You shouldn't believe me. I am the poet's husband. I cannot be trusted. I lie all the time. (I am a poet, after all.) But do you want to risk it? Can you live without its beauty? Would you want to even if you could survive?

This is one of the most effective books of visual poetry I've read, and one of the most accessible, even without ever giving us a complete phrase. These poems challenge us but they also draw us in and teach us how to read them. I want to read them again because I want to see them and I want to hear them and I want to discover what words I will slip into their beautifully milky voids.

_____

Huth, NF. this is visual poetry. chapbookpublisher.com: np, nd [2011]. US$10.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on April 01, 2011 20:14

March 31, 2011

National Poetry Month.ca Has Begun

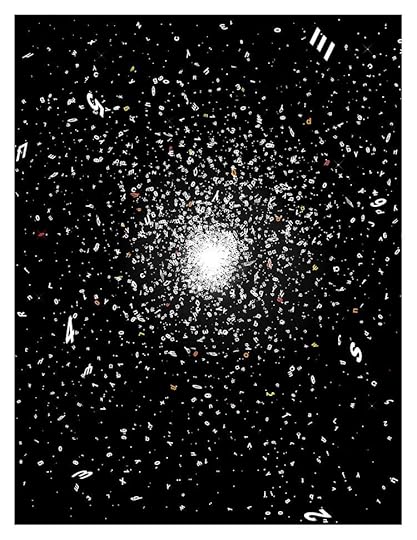

Eric Zboya, "Arecibo Silence"

Eric Zboya, "Arecibo Silence"The best National Poetry Month, the one Amanda Earl runs from Canada but with an international cast, the one focused on bringing us a new visual poem every day, has begun. So watch. That's all. Watch:

National Poetry Month.ca

ecr. l'inf.

Published on March 31, 2011 21:06

Hashtagging

Soon, I'll post here something unrelated to International Pwoermd Writing Month IV, but for now let me note that there is an official Twitter hashtag for this year's events:

#InterNaPwoWriMo

And we have 19 people participating. For details on them, visit the International Pwoermd Writing Month blog.

ecr. l'inf.

#InterNaPwoWriMo

And we have 19 people participating. For details on them, visit the International Pwoermd Writing Month blog.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on March 31, 2011 20:39

March 30, 2011

The InterNaPwoWriMo IV Twelve

Besides me, eleven other people have signed up to write at least one pwoermd a day for the month of April 2011. That won't make this the biggest celebration of International Pwoermd Writing Month, but with eight more folks it will.

There is still tomorrow (and, hey, even the next day) to sign up and make sure you make 30 pwoermds in a single month. That's almost a full chapbook of pwoermds!

Spread the word.

ecr. l'inf.

There is still tomorrow (and, hey, even the next day) to sign up and make sure you make 30 pwoermds in a single month. That's almost a full chapbook of pwoermds!

Spread the word.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on March 30, 2011 20:59

March 29, 2011

April Approacheth

ƏC, "y.ouu" (2010)

ƏC, "y.ouu" (2010)April, the cruelest month (at least to poets), arrives at the end of this week, and with it comes the Fourth International Pwoermd Writing Month (InterNaPwoWriMo IV). As usual, I will celebrate by posting at least one pwoermd a day to the InterNaPwoWriMo blog, which lies fallow for eleven months of the year in order to be ready for a full month's bloom in April.

Also as usual, I am looking for others to join me in celebrating this month. Last year, there were eighteen other participants in a number of countries and writing in various languages. Any language is acceptable, and visual pwoermds (like ƏC's above) are encouraged. So the only limit to this poems is that they can be no more than one word long and cannot have a title besides the title they themselves are.

I am assuming that one pwoermdist will be joining me, and that person is Mark Young. Since he never stopped writing a pwoermd a day since the end of April 2011, I assume he will be participating. His blog, Won Des Lait, is the place on the web you are most likely to find a pwoermd these days.

If you are interested in participating, drop me a line so I can add you to the rolls. For everyone else, enjoy what we end up producing.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on March 29, 2011 20:24