Geof Huth's Blog, page 27

June 2, 2011

Psocial Me/dia

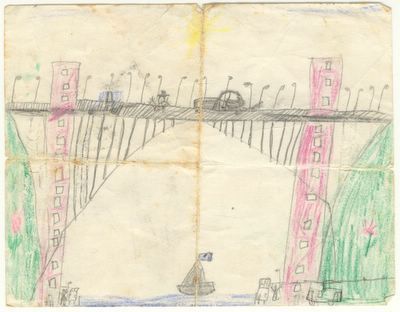

Geof Huth, "Ponte D. Luis, Porto, Portugal" (ca 1967, artist aged ca 7)

Geof Huth, "Ponte D. Luis, Porto, Portugal" (ca 1967, artist aged ca 7)For the past few weeks, I have existed on tumblr, the microblogging platform, where I have been publishing pwoermds, photographs, short audio poems, and occasional videos. All I really did was revive my old but short-lived tumblr blog, m+i+n+i+m, leaving it focused on minimalist poetry.

All of this revives the question of what social media are for for the poet and what the social media poet is. For it is abundantly evident that I publish considerably more poetic content (textual, visual, sound, and video poetry, as well as commentary on subjects poetic) on my blogs, tumblr, Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Vimeo, and Audioboo than I ever have published in journals and books in paper or digital form. I am my own editor, or my own lack of one.

And all of these online activities are automatically connected to each other in various ways. If I post a short audio piece to Audioboo, for example, it also posts to Facebook and Twitter, but both Facebook and Twitter consist primarily of content produced precisely for those venues. I decide, through processes both rigid and instinctual, what kind of material I'll post where, taking into account the culture of that particular venue.

This is what poetry is now: the presentation of self, the presentation of words (and of images [and of images of words]), links to other content, self-promotion, and the integration of poetry into the entirety of one's personal (and sometimes also professional life. All of this is good and all of it is dangerous.

Because social media are just another form of life.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on June 02, 2011 20:16

June 1, 2011

Fleshe of My Fleshe

Despite the well known and often expressed fact that there are too many poems in the world, despite the contention that poetry reduces the value of whatever it touches (paper, computer screen, the human mind), I continue to make poetry. I have even continued to make poetry after having just finished writing 365 poems, one a day for a year.

Why don't I stop, you might ask? Simple. I am a poet. Poets write poetry. To continue to be a poet, I have to write poetry. The other reason is that there's something comforting about concentrating on the construction of a set of words for a small time. That practice focuses me, calms me, removes everything else in my life, evaporates the walls and illusions around me, and gives me the purity of focus, and nothing else. Working words is my meditation. I am lost within the circular boundary of creation, a boundary line that wraps tight around me.

Most of the poems I'm creating are nanopoems: pwoermds (which extend never more than a word in length) and poems of a very short length created as I read other poetry. I create out of the experiences of my life, and sometimes these experiences are merely words on a page. I'm reading Charles Bernstein's Girly Man, and quickly, and his quirky humor and the word choices that compells him to use serve to rouse the somnolent poet within me.

But a couple of days ago I began to write other poems, without writing a poem at all. Every evening I receive an email that includes one entry from the Oxford English Dictionary, generally chosen at random. These are the OED's words of the day, and I take these entries, copy them in full and then delete the words I don't want, add linebreaks, and declare that I have written a poem. I doubt this technique will work with every entry that comes my way, some of which are quite lacking in length, but generally the definitions (often multiple senses) and illustrative quotations provide me a rich word stream to work from.

As I create these poems, all I am allowed to do is delete or add a linebreak. I cannot respell a word or add a word (though I did repeat a phrase in the first poem). I cannot change the capitalization of a word. But I can delete text and merge two sentences written decades apart into one sentence-like sequence. I can play with the language. And what I enjoy about the results is how these bits of text—left in their original order but twice torn out of their context—take on new meaning and significance in their new context.

A poem comes with text so context (syntactic, historic, topical) is always important. The latest of these entries is called "Flesh," which you will soon see is based on the verb form, not the more common noun form, of the word.

ecr. l'inf.

Why don't I stop, you might ask? Simple. I am a poet. Poets write poetry. To continue to be a poet, I have to write poetry. The other reason is that there's something comforting about concentrating on the construction of a set of words for a small time. That practice focuses me, calms me, removes everything else in my life, evaporates the walls and illusions around me, and gives me the purity of focus, and nothing else. Working words is my meditation. I am lost within the circular boundary of creation, a boundary line that wraps tight around me.

Most of the poems I'm creating are nanopoems: pwoermds (which extend never more than a word in length) and poems of a very short length created as I read other poetry. I create out of the experiences of my life, and sometimes these experiences are merely words on a page. I'm reading Charles Bernstein's Girly Man, and quickly, and his quirky humor and the word choices that compells him to use serve to rouse the somnolent poet within me.

But a couple of days ago I began to write other poems, without writing a poem at all. Every evening I receive an email that includes one entry from the Oxford English Dictionary, generally chosen at random. These are the OED's words of the day, and I take these entries, copy them in full and then delete the words I don't want, add linebreaks, and declare that I have written a poem. I doubt this technique will work with every entry that comes my way, some of which are quite lacking in length, but generally the definitions (often multiple senses) and illustrative quotations provide me a rich word stream to work from.

As I create these poems, all I am allowed to do is delete or add a linebreak. I cannot respell a word or add a word (though I did repeat a phrase in the first poem). I cannot change the capitalization of a word. But I can delete text and merge two sentences written decades apart into one sentence-like sequence. I can play with the language. And what I enjoy about the results is how these bits of text—left in their original order but twice torn out of their context—take on new meaning and significance in their new context.

A poem comes with text so context (syntactic, historic, topical) is always important. The latest of these entries is called "Flesh," which you will soon see is based on the verb form, not the more common noun form, of the word.

Flesh

To reward with a

portion of the flesh

to excite his eagerness

in wider sense, to render

eager by the taste of blood

Flesshe, as we do,

whan we gyve him any

parte of a wylde beest

much better flesh

made more cruell and eagre

with the tast of bloud

that had so fleshed them

fleshed to the game

there flesh'd with prey appears

Before they had fleshed the hounds

To initiate in or inure to

his fleshed and accustomed

to kyll men lyke shepe,

for he was then thorowly fleshed

in the slaughter of

well fleshed in blood

had been well fleshed

in the work of blood by

maiming and wounding herself

to render inveterate

enured and fleshed in ciuill spoile

fleshed to the Presse

to the sale

of our decayed Natures

Were not this a mere method

in leudness and wickedness

at these nimble

To inflame the ardour,

rage, or cupidity

to incite

that could haue flesht me

to thys vyolent deathe

that now they think

can stand before them

upon my shoulders

flesh'd with Slaughter

and with Conquest crown'd

To plunge into the flesh

to flesh our taintlesse swords

The wild dogge

Shal flesh his tooth

on euery innocent

So well hath fleshd

his maiden sword

his virgin-sword

to the haft

fleshed in the pike

one vpon another

his maiden pen

To gratify lust

in the spoyle of her honour

for plunder and revenge

To clothe with flesh;

embody in flesh

with some pleasant passages

so as to dwell in common human forms

gradually fleshed

A dainty bit

fleshed out and rendered

To fatten.

fig.

Flesh mee with Gold,

fat mee with Silver.

To remove the adhering flesh

cutting away the jagged extremities and offal,

the ears

and nostrils

Unhairing, fleshing, scudding.

To paint flesh-colour.

blue the coat and

colour the tablecloth

ecr. l'inf.

Published on June 01, 2011 19:24

May 31, 2011

I Was Real Once

Once, I was in the city of Manchester in a country called England in a hotel called Mint in a mint green bar with Nancy, with derek beaulieu, with Eduard Escoffet, with Moniek Darge, with Christian Bök, with Helen White—and the important person in this story is Helen, who made the observation.

Helen, sitting across from me at a tiny round table, with Moniek at her side and Nancy at mine, leaned across the table and said, "You are not real. You are not supposed to be real."

"What?" I thought or said, but in the middle of the spoken stream of her thought, and she continued, saying words in a certain order, words I do not recall exactly but words that I display here as if I can reproduce them perfectly.

"You are not real. You are a person from a blog, from another place, and Nancy is a character in that place."

And then I knew what she meant. As a child, I always pondered just how real any person could be when I was not in that particular person's presence, and I realized that I never felt the reality of anyone I was not with at a certain point in time. Only by co-inhabiting the same space with another could I believe in that person's realness.

"Right now you are real, but you will go away and stop being real again. And you will be a character on a blog."

So I was real once. I was right there, and unavoidable and thereby palpable and thus a necessary and incontrovertible fact. But no more. Now I am a cipher, a set of letters laid out in rows, words upon words, still images, signs of what a person might be, signs in space of what a person in personal space might be, and someone, either fictional or historical, who makes signs to prove his presence but signs of no stability or surety, signs that could not be believed, the equivalent of signs in a dream telling you you were never sleeping even though it was only sleeping that let those signs appear.

We are sleeplings, and we dream our world into existence. We cannot believe it is here, cannot prove it is here, wonder if we are nothing but thoughts floating free in empty space, though still looking for a place, a place to be, to be from, to go to, a way to be real, even though we know that is impossible.

I thought I was real once. Then I turned five and the tables turned on me. The yellowjackets descended in a stream out the bottom of a hive and came after me, and I ran from the woods as fast as I could, all the way through Virginia, faster than their stingers could fly, to a yellow house the color of yellowjackets but without the black stripes, and my cat Nicky broke his tail in a fight at night, and my father snipped the tail off at the break. This was before we took Nicky with us to Portugal and left him there. This was before I lived in Canada, before Barbados and Bolivia, before Ghana and Morocco and Somalia, before West Germany. Before I lived in DC, in the south, before New York State, before Syracuse and Horseheads and Johnstown and Rotterdam and Schenectady. (But after California.) Before I found myself at the Text Festival one evening in early May of this year, at the beginning of this very month, and learned, once again, that I am not real, but just an apparition, just a machine set to play words at a certain time, just a memory of something that never actually happened, even though we can't quite believe that it never did, even though we remember it so sharply that it takes our breath away.

ecr. l'inf.

Helen, sitting across from me at a tiny round table, with Moniek at her side and Nancy at mine, leaned across the table and said, "You are not real. You are not supposed to be real."

"What?" I thought or said, but in the middle of the spoken stream of her thought, and she continued, saying words in a certain order, words I do not recall exactly but words that I display here as if I can reproduce them perfectly.

"You are not real. You are a person from a blog, from another place, and Nancy is a character in that place."

And then I knew what she meant. As a child, I always pondered just how real any person could be when I was not in that particular person's presence, and I realized that I never felt the reality of anyone I was not with at a certain point in time. Only by co-inhabiting the same space with another could I believe in that person's realness.

"Right now you are real, but you will go away and stop being real again. And you will be a character on a blog."

So I was real once. I was right there, and unavoidable and thereby palpable and thus a necessary and incontrovertible fact. But no more. Now I am a cipher, a set of letters laid out in rows, words upon words, still images, signs of what a person might be, signs in space of what a person in personal space might be, and someone, either fictional or historical, who makes signs to prove his presence but signs of no stability or surety, signs that could not be believed, the equivalent of signs in a dream telling you you were never sleeping even though it was only sleeping that let those signs appear.

We are sleeplings, and we dream our world into existence. We cannot believe it is here, cannot prove it is here, wonder if we are nothing but thoughts floating free in empty space, though still looking for a place, a place to be, to be from, to go to, a way to be real, even though we know that is impossible.

I thought I was real once. Then I turned five and the tables turned on me. The yellowjackets descended in a stream out the bottom of a hive and came after me, and I ran from the woods as fast as I could, all the way through Virginia, faster than their stingers could fly, to a yellow house the color of yellowjackets but without the black stripes, and my cat Nicky broke his tail in a fight at night, and my father snipped the tail off at the break. This was before we took Nicky with us to Portugal and left him there. This was before I lived in Canada, before Barbados and Bolivia, before Ghana and Morocco and Somalia, before West Germany. Before I lived in DC, in the south, before New York State, before Syracuse and Horseheads and Johnstown and Rotterdam and Schenectady. (But after California.) Before I found myself at the Text Festival one evening in early May of this year, at the beginning of this very month, and learned, once again, that I am not real, but just an apparition, just a machine set to play words at a certain time, just a memory of something that never actually happened, even though we can't quite believe that it never did, even though we remember it so sharply that it takes our breath away.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on May 31, 2011 20:34

May 30, 2011

In the Corners

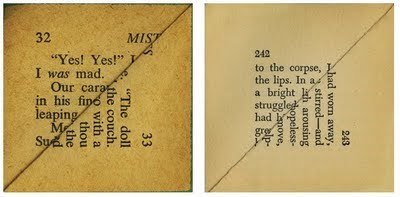

A poet with the visual word is someone who see text that other people never even imagine seeing. So is Erica Baum, whose new book, Dog Ear, just out from Ugly Duckling Presse, captivates with its visual presence and with its outré expectations about reading.

What this book is is something simple and beautiful, something shudderingly mind-changing in the smallest of ways. Maybe it is that I have stared at text with awe and passion too long in my life to make a reasoned judgment of such a work, but I think what I see is what others see, or at least should.

Baum, who is the tree from which the pages of this book is made, who is the tree of the pages of many book from which the pages of this book is made, does something very simple in this book, something no-one saw before, but something that brings the world suddenly into hyperfocus. For all that Baum has done is rifle through paperbacks dogearing the pages until the effects of the dogeared overlap lying onto the page behind it create some kind of poetry.

Poetry is always hidden from us, and only the poet can find what we cannot see. The features of these foldings that are amazing and many in number. The lines of the perfect equilateral triangle of the corner turned over always line up with the lines of the pages behind it, so lines going vertical feed into lines going horizontal, and we read as if the line is a right angle of sense. And these right angles make some kind of unexpected sense when we read across those angles. All of these bent-over corners are presented to us as enlarged squares of text, with perfect margins around their entirety (and sometimes with page numbers), and this size allows us to see the details of the text, the typefaces, and even the paper, which ranges wildly in color, from almost white to a cocoa brown. These are visual texts, texts that exist only in this manner on single copies of books we'll never see the originals of. But they captivate through their physicality nonetheless.

I could talk about the poetry of these works, but the book sandwiches these squares of beauty between two separate expanses of text that try to illuminate these for us. That is impossible. Take away the introduction. Take away the postface. They are fine. But unnecessary. Find these squares and see them. Find these squares and read them. In full color.

The simplicity of the greatest beauty is that we are surprised they have always been with us.

Erica Baum has saved us from our blindness.

_____

Baum, Erica. Dog Ear. Ugly Duckling Presse: Brooklyn, N.Y., 2011. US$20 (direct from the publisher)

ecr. l'inf.

Published on May 30, 2011 20:23

May 29, 2011

Done

Still Point, Caroga Lake, New York

I have furiously spent my last year writing, even more so than usual, and most furiously in the last two months, because I have been writing a poem, or many poems (one a day), each as a letter to someone I know, and each mailed out, on paper, to its intended recipient. I started on my fiftieth birthday (25 May 2010) and ended on my wife Nancy's fiftieth birthday (24 May 2011). As such, this was a celebration of being fifty, of reaching the half century mark, for on every day that I was fifty I wrote a letter to someone.

This project, which goes under the title 365 ltrs was meant, in a significant way, as a writing practice, a way to keep myself writing, but it was also meant to be a way of communicating with individuals I know, some I work with every work day, some whom I've grown up with, some I have never met but have known for years. I wrote to family members, to fellow poets, to fellow archivists, to fellow mailartists, and others. The plan was to make this project an act of giving. A poem may always be a gift, though the gift is often just for the the creating poet, but to succeed a poem must be a gift received with some quantity of pleasure. But a gift only need be given with such intent for it to be what it is. We cannot ensure all of our gifts will be accepted happily, but people often responded to me to thank me for the gifts, some responding with other creative works, which was a result I had hoped for. So far, 129 of them (about one third of the total) have not responded to my letters, some of them people I see frequently enough, but that is not a problem because a gift needs no gift of thanks in return. And I'm sure that some people were unsure how to deal with a sometimes strange poem appearing, unbidden and unannounced, in their mailbox.

A year is a long time, 365 days (and 366 in a long year), and much can happen in that time. Some people I wrote to in this project I didn't even know when I began the project, but sending them letters was what I needed to do. And two people died. My only aunt, or only blood aunt, died early this year, after struggling with emphysema for years. She called me after she had received her letter from me to say it was the best gift she'd ever received. It was sad to lose her to the cold bosom of eternity, but I was happy to write her while she was still alive--and she was the third person I wrote to, which I did to ensure I'd reach her in time. The other person who died was Art Reinhart, a friend and former colleague who was just days younger than I. He died by his own hand, which happens when life becomes too much for us, and I am sad he is dead but respect his decision about his own life. He didn't quite understand the strange poem I'd sent him, which was one I'd written in an airport and in flight, but he appreciated it enough to thank me.

As I have noted elsewhere, I had many goals in this project, and I had many ways of looking at the project. I didn't see it as little more than a project to write poems, even though that is what it was. Also, what the project was at the beginning was not quite what it was by its end. At the outset of the project, I had planned to write poems directly in the form of letters. The poems were always addressed to the recipient and they were reasonably informal pieces with few formal differences between them. Soon, I changed that tactic and tried to write poems as different from each other as I good, so poems within this project include poems in various poetic forms, light verse, sound poetry (three of the poems), visual poetry (27 of the poems), pwoermds, and all with as wide a variety of styles as I could manage.

I also wrote to many places: the vast majority of states in the United States, every continent except Antarctica, and many countries. Still most of my poems went to North America (313) and Europe (39), and of the rest of the continents only Asia (with 7) had more than one letter heading out to them. This almost was surprising to me, since I've live on most of those continents, but I now know hardly anyone I knew in childhood. As expected, the enormous majority of letter went to people in the US (297), with my own state of New York accounting for 105 of those. As you can see, this was and is and will be a statistical project, which statistics I'll compile in their totality as part of the final project.

Because the important fact to note is that this project cannot be done now. All I've done so far is write the first draft of hundreds of poems. I still have to try to make these poems into usable poems. Certainly, that isn't necessary for the project to work, in my mind, but it's part of the work.

As I created this project, posting each of the poems online, I added tags to identify the poems, by recipient, location of recipient, type of poem, and how I primarily knew the recipient. Most recipients were either poets (158) or archivists (84), but I also wrote to 21 friends (those friends whom I didn't know as archivists or poets), 41 family members, 19 mailartists, 9 artists, and a number of miscellaneous characters (a doctor, two collectors, etc.). Forty of the people, I identified as couples, because I wrote a poem both pairs of people who were couples of some kind.

The poems are also identified as to event. At least 63 of them were letters sent on the occasion of a birthday, and three were condolences. The purposes of letters are various, as are those of poems. Writing is a process of connecting, just as speaking it. Sometimes we do it well, and sometimes not. I wrote over a wide range of quality over the course of this year. In the end, all I can say is that the only reward is the poem. The only reward is always the poem, whether the poem works or not.

ecr. l'inf.

I have furiously spent my last year writing, even more so than usual, and most furiously in the last two months, because I have been writing a poem, or many poems (one a day), each as a letter to someone I know, and each mailed out, on paper, to its intended recipient. I started on my fiftieth birthday (25 May 2010) and ended on my wife Nancy's fiftieth birthday (24 May 2011). As such, this was a celebration of being fifty, of reaching the half century mark, for on every day that I was fifty I wrote a letter to someone.

This project, which goes under the title 365 ltrs was meant, in a significant way, as a writing practice, a way to keep myself writing, but it was also meant to be a way of communicating with individuals I know, some I work with every work day, some whom I've grown up with, some I have never met but have known for years. I wrote to family members, to fellow poets, to fellow archivists, to fellow mailartists, and others. The plan was to make this project an act of giving. A poem may always be a gift, though the gift is often just for the the creating poet, but to succeed a poem must be a gift received with some quantity of pleasure. But a gift only need be given with such intent for it to be what it is. We cannot ensure all of our gifts will be accepted happily, but people often responded to me to thank me for the gifts, some responding with other creative works, which was a result I had hoped for. So far, 129 of them (about one third of the total) have not responded to my letters, some of them people I see frequently enough, but that is not a problem because a gift needs no gift of thanks in return. And I'm sure that some people were unsure how to deal with a sometimes strange poem appearing, unbidden and unannounced, in their mailbox.

A year is a long time, 365 days (and 366 in a long year), and much can happen in that time. Some people I wrote to in this project I didn't even know when I began the project, but sending them letters was what I needed to do. And two people died. My only aunt, or only blood aunt, died early this year, after struggling with emphysema for years. She called me after she had received her letter from me to say it was the best gift she'd ever received. It was sad to lose her to the cold bosom of eternity, but I was happy to write her while she was still alive--and she was the third person I wrote to, which I did to ensure I'd reach her in time. The other person who died was Art Reinhart, a friend and former colleague who was just days younger than I. He died by his own hand, which happens when life becomes too much for us, and I am sad he is dead but respect his decision about his own life. He didn't quite understand the strange poem I'd sent him, which was one I'd written in an airport and in flight, but he appreciated it enough to thank me.

As I have noted elsewhere, I had many goals in this project, and I had many ways of looking at the project. I didn't see it as little more than a project to write poems, even though that is what it was. Also, what the project was at the beginning was not quite what it was by its end. At the outset of the project, I had planned to write poems directly in the form of letters. The poems were always addressed to the recipient and they were reasonably informal pieces with few formal differences between them. Soon, I changed that tactic and tried to write poems as different from each other as I good, so poems within this project include poems in various poetic forms, light verse, sound poetry (three of the poems), visual poetry (27 of the poems), pwoermds, and all with as wide a variety of styles as I could manage.

I also wrote to many places: the vast majority of states in the United States, every continent except Antarctica, and many countries. Still most of my poems went to North America (313) and Europe (39), and of the rest of the continents only Asia (with 7) had more than one letter heading out to them. This almost was surprising to me, since I've live on most of those continents, but I now know hardly anyone I knew in childhood. As expected, the enormous majority of letter went to people in the US (297), with my own state of New York accounting for 105 of those. As you can see, this was and is and will be a statistical project, which statistics I'll compile in their totality as part of the final project.

Because the important fact to note is that this project cannot be done now. All I've done so far is write the first draft of hundreds of poems. I still have to try to make these poems into usable poems. Certainly, that isn't necessary for the project to work, in my mind, but it's part of the work.

As I created this project, posting each of the poems online, I added tags to identify the poems, by recipient, location of recipient, type of poem, and how I primarily knew the recipient. Most recipients were either poets (158) or archivists (84), but I also wrote to 21 friends (those friends whom I didn't know as archivists or poets), 41 family members, 19 mailartists, 9 artists, and a number of miscellaneous characters (a doctor, two collectors, etc.). Forty of the people, I identified as couples, because I wrote a poem both pairs of people who were couples of some kind.

The poems are also identified as to event. At least 63 of them were letters sent on the occasion of a birthday, and three were condolences. The purposes of letters are various, as are those of poems. Writing is a process of connecting, just as speaking it. Sometimes we do it well, and sometimes not. I wrote over a wide range of quality over the course of this year. In the end, all I can say is that the only reward is the poem. The only reward is always the poem, whether the poem works or not.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on May 29, 2011 11:43

May 27, 2011

It is Too Late for Writing

and, though it is so late, I decide to write as a way to keep from writing. I have this urge to write a poem. And only that because I am a poet, which is nothing more than a person who writes poems. Or maybe sometimes a machine that does. The word "machine" spins between meanings as if trapped, and propelled within that trap between opposing magnetic sources.

Strangely, almost inexplicably, I had the desire to write a poem tonight, this night slipping towards morning. Truth is I haven't stopped making poems since I finished my obese 365 ltrs project. I've just focused on visual poems and have kept most of them (it has been four days already) to myself.

My mind is always moving, not necessarily forward, maybe churning in place, but it moves, and that movement sometimes requires outlet, mandates that something be made to record, to memorialize that moving. Words are moving insofar as they convince people to feel something they would not have felt on their own. But that is their value.

I am sipping an armagnac, and slowly, because it is sweet but with a deep flavor like what I would imagine roasted vanilla to have, and because it is the one liquor that sometimes makes me sleepy. Sleep seems necessary, even if inconvenient. With a big project done, my biggest of quite a few yearlong projects I have undertaken in my diminishing time here, there is a little gap in my life, which I filled today by trying to get our wireless printer to work and by cleaning up my accumulated email.

But there is no gap. I have so many projects I have finished through a first draft, so many books of poems, and I need to return to finish them, if only to have the sense that I've accomplished something, the sense that there's some way to save these words from uselessness, to make them work.

So I work a few more words out, as I work it out, as I hope to work it out. I am a writer, which means I write words. It doesn't mean they are good or moving or that there is any importance attached to them, and I care about all of that only secondarily. My primary purpose is to prove my existence and to give myself a voice, for every human needs a voice, no matter how small or little heard, because we need to be and because sometimes we also have to be after we are no more.

The weather has cooled slightly, the night is dark and leaning into humid, and I am the last one left awake in a house, because I am the one who needs to write, with all the little of me there is.

ecr. l'inf.

Strangely, almost inexplicably, I had the desire to write a poem tonight, this night slipping towards morning. Truth is I haven't stopped making poems since I finished my obese 365 ltrs project. I've just focused on visual poems and have kept most of them (it has been four days already) to myself.

My mind is always moving, not necessarily forward, maybe churning in place, but it moves, and that movement sometimes requires outlet, mandates that something be made to record, to memorialize that moving. Words are moving insofar as they convince people to feel something they would not have felt on their own. But that is their value.

I am sipping an armagnac, and slowly, because it is sweet but with a deep flavor like what I would imagine roasted vanilla to have, and because it is the one liquor that sometimes makes me sleepy. Sleep seems necessary, even if inconvenient. With a big project done, my biggest of quite a few yearlong projects I have undertaken in my diminishing time here, there is a little gap in my life, which I filled today by trying to get our wireless printer to work and by cleaning up my accumulated email.

But there is no gap. I have so many projects I have finished through a first draft, so many books of poems, and I need to return to finish them, if only to have the sense that I've accomplished something, the sense that there's some way to save these words from uselessness, to make them work.

So I work a few more words out, as I work it out, as I hope to work it out. I am a writer, which means I write words. It doesn't mean they are good or moving or that there is any importance attached to them, and I care about all of that only secondarily. My primary purpose is to prove my existence and to give myself a voice, for every human needs a voice, no matter how small or little heard, because we need to be and because sometimes we also have to be after we are no more.

The weather has cooled slightly, the night is dark and leaning into humid, and I am the last one left awake in a house, because I am the one who needs to write, with all the little of me there is.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on May 27, 2011 22:16

May 26, 2011

In the Realm of Being

Geof Huth reads "365. In the Realm of Being" to Nancy Huth (24 May 2011)

On Tuesday, the 24th of May 2011, I wrote the 365th poem for my 365 ltrs project, a huge rambling set of poems written one a day over the course of an entire year. This 365th poem was to my wife Nancy Huth, who celebrated her fiftieth birthday on that day, the last day I myself was fifty. I stayed home for the entire day to write this poem, a fifty-page poem in fifty sections, and I finished it after 10:00 pm that night. Then I read the entire poem to Nancy, over the course of 47 minutes, recording it as I did. This audio is that first, and maybe last, performance of that poem. The day was Magic Day, that one day of the year when Nancy and I are the same age. The title of the poem is "365. In the Realm of Being."

ecr. l'inf.

Published on May 26, 2011 18:19

May 25, 2011

I Don't Care about Health

I'm not here to survive, nor to be a great poet. I'm here to test, and testing doesn't mean succeeding. Truth be told, I never think I succeed at all. Out of 100 poems I write, I might think one is okay. Quality is not my guide. Attempting is. I don't think I'm an avant-garde poet (in part because there is no avant garde anymore), but if I were I'd say that a focus on quality is a bourgeois obsession, one in which you give yourself over to the myth of greatness. I have no myths, not Christian, not poetic.

I am a poet, which means I make poems, most of which are terrible, because most poems are terrible, and I'm not one with the gods in the realm of greatness. So I've just finished a massive and physically brutal project that produced one poem a day for an entire year. A poet might see that and think of it as a poetic project, and that would be a good conclusion.

But it was a personal project: I was connecting physically with people I know. I sent these poems out to people as gifts in the mail. I sent these out without stop even though about one third of the people never responded to these mailings. This was a human act of connection. That was an important part of the project.

It was a mailart project: I sent these letters to mailartists, who now work in such predictable ways that they might not recognize that these letters were sent as mailart, that the act of sending art, especially art meant to exist beyond the bounds of the canon, is an act of mailart, an act of subterfuge against the hegemony of the artwork, writ large.

It was a performance project: I performed the act of these poems in public. I wrote the poems nightly and posted them online as I went so people could watch the progress made, the errors I made, the effects of sleep deprivation, the variety I could bring to the project, and the staid repetition I could not avoid.

It was a physical project: This was a project of endurance, one of physical endurance. How hard could I work, how little sleep could I get, how much could I write and still function the next day, since I have a busy and fulltime job.

It was a conceptual project: This project was a project designed around a number of constraints: temporal, numerical, gender-based. I wrote to men half the time and to women the other half. I wrote daily, and I wrote to every continent except Antarctica. The project has meaning through a huge number of seeming coincidences of its production.

It was a celebratory project: I celebrated the fact of being 50, an age I could easily have never reached, a numerically significant age, and I did it daily, and I did it with poems that were almost all fairly long. Because life is about excess or it is about withering. I didn't wither.

It was an experimental project: I needed to find how many different kinds of poems I could write in a year, how different I could be, and I failed at this most, but I failed while still producing a wide range of work in many different styles and forms.

Plenty of people complain about a lack of quality in such work, but that is beside the point of the work. These poems are not produced for publication, and the 1500-page book is not meant for publication. It is meant to exist as a monument to its own production, to the act of creation, the act of proving one's existence, the act of trying, but failing, to escape from my own drastic limitations. I would have loved it if I ended and thought that all or most or half, or even 10% of the poems in this book were any good. They are not, but the project holds for me.

I am a poet of failure. Failure is my art. That is what this is about.

Last summer, Tom Beckett and Nancy tried to get me to stop the project, thinking it was too much for me, too much of a physical burden, and I'm sure it was. But I survived. If I had died, that would have been a part of the project, and an essential part. But I did not. And I did not think I would. I thought that one thing I could do is write these poems obsessively and bloodily, through physical duress, and complete the project. And the writing became so that I actually wrote much more in the last two months than I had, on average, over the first ten. I didn't lose energy. I built momentum.

Later today, I'll review some of the statistics of the project and why I did it. I'm proud of the project, even though I'd say there are only four good poems in it, and none of them great. I am about quantity. I believe in quantity, as an esthetic value, not one over quality, but one comparable to it. I believe in the conceptual meaning of quantity, and I believe that quantity proves something though it doesn't prove the value of a poem.

Ask Nancy, my wife Nancy, whose poems bookend this project. Almost every night, I read her these poems, and on almost each of those nights I told her the poem I had written was terrible. Because they were. I tried to write good poems, not great ones, and I wrote bad ones, but mine was not only a poetic act. It was a human one.

Only connect.

ecr. l'inf.

I am a poet, which means I make poems, most of which are terrible, because most poems are terrible, and I'm not one with the gods in the realm of greatness. So I've just finished a massive and physically brutal project that produced one poem a day for an entire year. A poet might see that and think of it as a poetic project, and that would be a good conclusion.

But it was a personal project: I was connecting physically with people I know. I sent these poems out to people as gifts in the mail. I sent these out without stop even though about one third of the people never responded to these mailings. This was a human act of connection. That was an important part of the project.

It was a mailart project: I sent these letters to mailartists, who now work in such predictable ways that they might not recognize that these letters were sent as mailart, that the act of sending art, especially art meant to exist beyond the bounds of the canon, is an act of mailart, an act of subterfuge against the hegemony of the artwork, writ large.

It was a performance project: I performed the act of these poems in public. I wrote the poems nightly and posted them online as I went so people could watch the progress made, the errors I made, the effects of sleep deprivation, the variety I could bring to the project, and the staid repetition I could not avoid.

It was a physical project: This was a project of endurance, one of physical endurance. How hard could I work, how little sleep could I get, how much could I write and still function the next day, since I have a busy and fulltime job.

It was a conceptual project: This project was a project designed around a number of constraints: temporal, numerical, gender-based. I wrote to men half the time and to women the other half. I wrote daily, and I wrote to every continent except Antarctica. The project has meaning through a huge number of seeming coincidences of its production.

It was a celebratory project: I celebrated the fact of being 50, an age I could easily have never reached, a numerically significant age, and I did it daily, and I did it with poems that were almost all fairly long. Because life is about excess or it is about withering. I didn't wither.

It was an experimental project: I needed to find how many different kinds of poems I could write in a year, how different I could be, and I failed at this most, but I failed while still producing a wide range of work in many different styles and forms.

Plenty of people complain about a lack of quality in such work, but that is beside the point of the work. These poems are not produced for publication, and the 1500-page book is not meant for publication. It is meant to exist as a monument to its own production, to the act of creation, the act of proving one's existence, the act of trying, but failing, to escape from my own drastic limitations. I would have loved it if I ended and thought that all or most or half, or even 10% of the poems in this book were any good. They are not, but the project holds for me.

I am a poet of failure. Failure is my art. That is what this is about.

Last summer, Tom Beckett and Nancy tried to get me to stop the project, thinking it was too much for me, too much of a physical burden, and I'm sure it was. But I survived. If I had died, that would have been a part of the project, and an essential part. But I did not. And I did not think I would. I thought that one thing I could do is write these poems obsessively and bloodily, through physical duress, and complete the project. And the writing became so that I actually wrote much more in the last two months than I had, on average, over the first ten. I didn't lose energy. I built momentum.

Later today, I'll review some of the statistics of the project and why I did it. I'm proud of the project, even though I'd say there are only four good poems in it, and none of them great. I am about quantity. I believe in quantity, as an esthetic value, not one over quality, but one comparable to it. I believe in the conceptual meaning of quantity, and I believe that quantity proves something though it doesn't prove the value of a poem.

Ask Nancy, my wife Nancy, whose poems bookend this project. Almost every night, I read her these poems, and on almost each of those nights I told her the poem I had written was terrible. Because they were. I tried to write good poems, not great ones, and I wrote bad ones, but mine was not only a poetic act. It was a human one.

Only connect.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on May 25, 2011 21:43

May 24, 2011

The 365th of 365 ltrs

Today, after a year of working on this project, I wrote the final poem of my 365 ltrs project, a 50-page poem to my wife. Tomorrow, I will post a few thoughts about this project, but tonight I'm going to bed before midnight, something I rarely do and have done even less often in the last year.

ecr. l'inf.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on May 24, 2011 19:59

May 22, 2011

A Slip of the History of Visual Poetry in Progress

The vispoetic sequence "totems" by Satu Kaikkonen is now available at the webzine Peep/Show edited by Lynn Behrendt and Anne Gorrick, and it is a part of an issue focused on international visual poetry that is curated by me.

I once said that Satu Kaikkonen included the entire history of visual poetry within her oeuvre. I said this because it was essentially true, because Satu had been creating visual poetry for about 18 months by then and had moved through all the major methods of making visual poetry and done them just about in order--and had done this without knowing what that order was.

Satu is a marvel. She is hugely industrious (which is a common trait--some say a weakness--of visual poets), and she is monstrously imaginative. Her visual poems have taken shape in any way I can conceive of a visual poem of taking shape. She has created shaped poems (for example), pwoermds (at the periphery of visual poetry), asemic writing, asemic comics, object poems, and much much more. If we wanted the world rich enough to justify living upon it, we would insist that Satu's only job be to produce her art.

So, after that bit of sideshow barking, hie yourself to Peep/Show to take a look at what Satu, one of the great visual poets, and one of the greatest Finland has ever produced, has made for you this time. And now Satu has progressed enough that she is not showing you history. She is showing you the future.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on May 22, 2011 20:38