Geof Huth's Blog, page 35

March 5, 2011

The Panelist

№ Press, headed up by derek beaulieu, published numerous little pamphlets over the course of a year, and their focus is often visual poetry, and the farthest reaches of that realm, the area almost devoid of language, the chillingly beautiful permafrost realm of visual poetry, where the letter is left to its own devices and often twisted to a point just before dissolution into transmogrified chaos—senseless as word but echoing with a hollow yet deep meaning that we can feel within our throbbing ribcages.

Gary Barwin is a kind of artist that should be impossible to exist: a solid poet (and why have I wasted my time not writing about his most recent book The Porcupinity of the Stars), an accomplished musician and composer, and a visual poet whose very eye for moving text into unexpected configurations draws a gasp out of me almost every time, as if I'd been hit hard in the gut unexpectedly, and enough to make my head spin towards dizziness.

So I am pleased to have copies of two beautiful № Press pamphlets by Gary Barwin, whom I must admit is my brother in spirit if not fact.

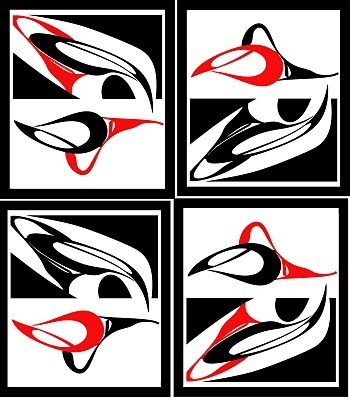

The first of these pamphlets, at least in numerical order and by the order of my reading them (though not chronologically in the order of their printing), is "Four Panels," a small blue-grey pamphlet of laid paper, and opening it reveals a single square sheet of paper tipped in on the recto page. This square is divided into four squares, each divided horizontally in two, one have backgrounded in white, the other in black, and within each of these squares, five minuscule e's, each dramatically distorted, as if they were pieces of plasticine that could be twisted into any shape, rest, but rest as if floating as oil within water. They are alive with and in their transformed shapes.

A bit of the magic of Qage here, the magic of the purity of letterforms, so the lower-case e is the focus because it is such a dense and beautiful letter, full of curves, but always straightened into place by that horizontal line that defines the lower edge of its bowl. So the poetry here is the focus on that e, but also the shapes the e is made into, and how those twistings never quite disguise the essence of the e for us. And the purity of the visual, the black against the white, and the surprising intervention of red, all bring this into balance, unwieldy and precarious balance, sure, but that is the only balance we would ever want.

The second of these pamphlets is larger, by about 50%. "Six Panels" is an untextured white card, folded in half, into a simple pamphlet, and on the inside is tipped in a simple little graphic poem, on a cream linen sheet. You could sleep and dream within the bed made of this poem.

The poem has only one character of text, the ampersand (&), but that is an important character in Gary's poetic imagination. The & is to Barwin as the H is to Nichol. It is his talisman, his touchstone, the point at which his imagination is released. This twisting bit of text is the Latin word for "and" ("et") pretzeled into something like the knotted flowing of thought, and it is an importantly Qagey character, one that appears in many different forms. It is a shapeshifter, something that means one things but can do it from many different visual versions of itself.

Gary uses the ampersand because it is so beautiful and because it is a remarkably efficient little grammalogue, telling us an entire word within the mere extent of a single character. But it is more than that. The & is a possibility, and Gary is always making something greater and better and bigger out of it.

This poems is divided into six panels—its name may have given you that thought without your even ever seeing it—and they are panels of various sizes of rounded rectangles, all of them separated from their brethren by channels of white space, which represent absence, blankness nothingness, for the panels are windows into the text, and the text is a etchinglike view of a ribcage, sans heart, sans lungs, sans anything. Wrapped within and among the bones of this ribcage, this hollowed-out chest, are the two legs and the two bowls of a dramatically serifed ampersand, the emperor of all letters, the letter that follows the zee, the zed, the izzard of the alphabet.

And this ampersand sometimes overlaps a rib, sometimes flows under it, and sometimes disappears in the jump from one rib to another. The ampersand is the heart and the lungs of the ribcage, which is the heart of the body, with is the engine of the sound and the mind and the bellowing bellows of the voice. In silence and seeming so, this poem of sight, this humble quiet little poem speaks the poem of the body and the self, the unexpected and beautiful thought that wakes us to the fact that we are, indeed, human beasts, something better than the beautiful dumb beasts around us, that we are the makers of meaning and the breathing of that meaning forth into something as simple and vital as breath.

_____

Barwin, Gary. Six Panels. № Press: Calgary, January 2011.

__________. Four Panels. № Press: Calgary, February 2011.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on March 05, 2011 20:50

March 4, 2011

Films Watched in February 2011

This past month, I actually watched more than one film a day, thanks to watching, in a theater, every animated and live-action short nominated for an Oscar, but I'm still behind my schedule of watching one film a day. Some good films this month, starting with one of my favorite comedies, which I watched on a snow day. For a period of time, the films I was watching were rarely in English.

February 2, 2011

1. Groundhog Day (101 min, Harold Ramis, 1993)

February 3, 2011

2. The Name of the Rose (130 min, Jean-Jacque Annaud, 1986)

February 4, 2011

3. Tarnation (88 min, Jonathan Caouette, 2003)

February 5, 2011

4. Departures (130 min, Yôjirô Takita, 2008)

February 6, 2011

5. Exit through the Gift Shop (87 min, Banksy, 2010)

February 7, 2011

6. Death in Venice (130 min, Luchino Visconti, 1971)

February 8, 2011

7. Dune (137 min, David Lynch, 1984)

February 9, 2011

8. Still-A-Life (1 min, Hedya Klein, 2008)

9. The Return of Spinal Tap (110 min, Jim Di Bergi, 1992)

February 12, 2011

10. Somewhere (97 min, Sofia Coppola, 2010)

February 16, 2011

11. Let Me In (116 min, Matt Reeves, 2010)

February 18, 2011

12. Ringu (96 min, Hideo Nakata, 1998)

February 19, 2011

13. Ringu 2 (96 min, Hideo Nakata, 1998)

February 20, 2011

14. The Confession (26 min, Tanel Toom, 2010)

15. Wish 143 (23 min, Ian Barnes, 2009)

16. Na Wewe (19 min, Ivan Goldschmidt, 2010)

17. The Crush (15 min, Michael Creagh, 2010)

18. God of Love (18 min, Luke Matheny, 2010)

19. Madagascar, Carnet de Voyage (11 min, Bastien Dubois, 2010)

20. Let's Pollute (6 min, Geefwee Boedoe, 2010)

21. The Gruffalo (26 min, Jacob Schuh and Max Lang, 2010)

22. The Lost Thing (15 min, Andrew Ruhema, 2010)

23. Day & Night (6 min, Teddy Newton, 2010)

24. URS (10 min, Moritz Mayerhofer, 2010)

25. The Cow Who Wanted to Be a Hamburger (6 min, Bill Plympton, 2010)

February 23, 2011

26. Ringu 0 (99 min, Norio Tsuruta, 2000)

February 27, 2011

27. Tesis (121 min, Alejandro Amenábar, 1996)

28. Henry Fool (137 min, Hal Hartley, 1996)

29. Danse (2 min, Peter Ciccariello, 1975)

February 28, 2011

30. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead (117 min, Tom Stoppard, 1990)

ecr. l'inf.

February 2, 2011

1. Groundhog Day (101 min, Harold Ramis, 1993)

February 3, 2011

2. The Name of the Rose (130 min, Jean-Jacque Annaud, 1986)

February 4, 2011

3. Tarnation (88 min, Jonathan Caouette, 2003)

February 5, 2011

4. Departures (130 min, Yôjirô Takita, 2008)

February 6, 2011

5. Exit through the Gift Shop (87 min, Banksy, 2010)

February 7, 2011

6. Death in Venice (130 min, Luchino Visconti, 1971)

February 8, 2011

7. Dune (137 min, David Lynch, 1984)

February 9, 2011

8. Still-A-Life (1 min, Hedya Klein, 2008)

9. The Return of Spinal Tap (110 min, Jim Di Bergi, 1992)

February 12, 2011

10. Somewhere (97 min, Sofia Coppola, 2010)

February 16, 2011

11. Let Me In (116 min, Matt Reeves, 2010)

February 18, 2011

12. Ringu (96 min, Hideo Nakata, 1998)

February 19, 2011

13. Ringu 2 (96 min, Hideo Nakata, 1998)

February 20, 2011

14. The Confession (26 min, Tanel Toom, 2010)

15. Wish 143 (23 min, Ian Barnes, 2009)

16. Na Wewe (19 min, Ivan Goldschmidt, 2010)

17. The Crush (15 min, Michael Creagh, 2010)

18. God of Love (18 min, Luke Matheny, 2010)

19. Madagascar, Carnet de Voyage (11 min, Bastien Dubois, 2010)

20. Let's Pollute (6 min, Geefwee Boedoe, 2010)

21. The Gruffalo (26 min, Jacob Schuh and Max Lang, 2010)

22. The Lost Thing (15 min, Andrew Ruhema, 2010)

23. Day & Night (6 min, Teddy Newton, 2010)

24. URS (10 min, Moritz Mayerhofer, 2010)

25. The Cow Who Wanted to Be a Hamburger (6 min, Bill Plympton, 2010)

February 23, 2011

26. Ringu 0 (99 min, Norio Tsuruta, 2000)

February 27, 2011

27. Tesis (121 min, Alejandro Amenábar, 1996)

28. Henry Fool (137 min, Hal Hartley, 1996)

29. Danse (2 min, Peter Ciccariello, 1975)

February 28, 2011

30. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead (117 min, Tom Stoppard, 1990)

ecr. l'inf.

Published on March 04, 2011 20:59

March 3, 2011

March 2, 2011

Books Read in February 2011

It is hard to imagine, at least for myself, that I made it through February having read only eight books, and most of them of a remarkably modest length. Still, I am busier that I usually am, sometimes with nothing more than shoveling snow (this having been the fifth, I think, snowiest winter around here). And I did spend a solid week of this past month traveling. Still, some interesting reading this year, and worth the effort. I just feel a little too little filled with words this past month.

February 2, 2011

1. Olsen, Geoffrey. End Notebook. Petrichord Books: Cambridge, Mass., 2008.

February 5, 2011

2. Maples Arce, Manuel. City: Bolshevik Super-Poem in 5 Cantos. Translated by Brandon Holmquest. Ugly Duckling Presse: Brooklyn, N.Y., 2010.

February 9, 2011

3. Bantjes, Marian. I Wonder. The Monacelli Press: New York, 2010.

February 10, 2011

4. Jones, Jonathan. oncept. fullcrumb horseries no. 3. the sticky pages press: Brussels, 2011.

February 13, 2011

5. Baker, Ed. Stone Girl E-pic. Leafe Press: Nottingham, U.K., and Claremont, Calif., 2011.

February 20, 2011

6. Thorson, Maureen. Applies to Oranges. Ugly Duckling Presse: Brooklyn, N.Y., 2011.

February 26, 2011

7. Colby, Kate. Return of the Native. Ugly Duckling Presse: Brooklyn, N.Y., 2011.

8. Yván, Yauri. Fire Wind. Ugly Duckling Presse: Brooklyn, N.Y., 2011.

ecr. l'inf.

February 2, 2011

1. Olsen, Geoffrey. End Notebook. Petrichord Books: Cambridge, Mass., 2008.

February 5, 2011

2. Maples Arce, Manuel. City: Bolshevik Super-Poem in 5 Cantos. Translated by Brandon Holmquest. Ugly Duckling Presse: Brooklyn, N.Y., 2010.

February 9, 2011

3. Bantjes, Marian. I Wonder. The Monacelli Press: New York, 2010.

February 10, 2011

4. Jones, Jonathan. oncept. fullcrumb horseries no. 3. the sticky pages press: Brussels, 2011.

February 13, 2011

5. Baker, Ed. Stone Girl E-pic. Leafe Press: Nottingham, U.K., and Claremont, Calif., 2011.

February 20, 2011

6. Thorson, Maureen. Applies to Oranges. Ugly Duckling Presse: Brooklyn, N.Y., 2011.

February 26, 2011

7. Colby, Kate. Return of the Native. Ugly Duckling Presse: Brooklyn, N.Y., 2011.

8. Yván, Yauri. Fire Wind. Ugly Duckling Presse: Brooklyn, N.Y., 2011.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on March 02, 2011 19:44

March 1, 2011

February 28, 2011

Poetics (77-79)

77. Words

A poet told me that he does not make money with words, do work with words, because he doesn't want to use the same tool he uses to make art to make money. I indelicately said, "But you use words to ask for toilet paper."

The word isn't separate from our lives or of a different part of it. The word is the human thing we use in a human way to make human sense, and the human is various and contradictory, just as the use and even meaning of words is various and contradictory. The word is for hate for love for boredom for ecstasy for everything.

There would be no point to poetry if all it took to make a poem was to use language and poetry would come up naturally out of it. The only reason a poem can be a magical experience, in those rare instances that it is, is because it uses, merely, language, the same language we use to argue about whose fault it was that we didn't understand each other when we both spoke.

78. Meaninglessness

Now that the time of my having read it is too long in the past, at least 26 years, I can't say what it was that Richard Hugo meant when he said it, but I will take the words anyway:

The poem must be meaningless.

And so it must be, and so it cannot, but the poem must strive towards meaninglessness even as it moves through meaning. The poem must become an experience of sound or shape, a kind of lung or muscle of an experience. It must become itself and reject the sense heaped upon it, for the poem that teaches us anything is our enemy.

79. Gotta

Henry Fool, the writer, the memoirist, said it: "Poet's gotta be able to contemplate anything." If the poet can't think about anything, the poet can't think of anything.

ecr. l'inf.

A poet told me that he does not make money with words, do work with words, because he doesn't want to use the same tool he uses to make art to make money. I indelicately said, "But you use words to ask for toilet paper."

The word isn't separate from our lives or of a different part of it. The word is the human thing we use in a human way to make human sense, and the human is various and contradictory, just as the use and even meaning of words is various and contradictory. The word is for hate for love for boredom for ecstasy for everything.

There would be no point to poetry if all it took to make a poem was to use language and poetry would come up naturally out of it. The only reason a poem can be a magical experience, in those rare instances that it is, is because it uses, merely, language, the same language we use to argue about whose fault it was that we didn't understand each other when we both spoke.

78. Meaninglessness

Now that the time of my having read it is too long in the past, at least 26 years, I can't say what it was that Richard Hugo meant when he said it, but I will take the words anyway:

The poem must be meaningless.

And so it must be, and so it cannot, but the poem must strive towards meaninglessness even as it moves through meaning. The poem must become an experience of sound or shape, a kind of lung or muscle of an experience. It must become itself and reject the sense heaped upon it, for the poem that teaches us anything is our enemy.

79. Gotta

Henry Fool, the writer, the memoirist, said it: "Poet's gotta be able to contemplate anything." If the poet can't think about anything, the poet can't think of anything.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on February 28, 2011 20:59

February 27, 2011

The Marks of a Poem

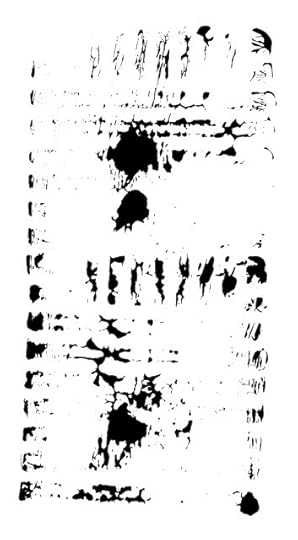

The online journal, Peep/Show, continues to reveal its international visual poetry issue, this time presenting us with the work of Tim Gaze, whose work in asemic visual poetry brings us to or beyond the edge of the textual. Tim has focused his attention on the action of taking mute and unrecognizable marks and saying something with it. Or allowing us to see something said within it.

This is not at all a new way for visual poetry, as it's at least decades old, but it still is a form of visual poetry that can cause a ruckus because it fiddles quite heavily with people's expectations of what "poetry" (and even "visual poetry") might be. But when I look into this expressive blots and smudges of ink I am pushed back to the later work of Bob Cobbing, who, with the power of pre-digital xerography, pushed the textual to or beyond the edge of the textual.

I like what I see in such experiments in expressive unexpressiveness.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on February 27, 2011 20:59

February 26, 2011

February 25, 2011

Poetics (76 Only)

The Silversmith, Room 404, Chicago, Illinois

76. How

I hope these words help you a little. It's good you're a poet because it's good to have poets around us, so I'll suggest below a few things you can work on in your poetry.

That last poem you sent me is definitely your best. I've read through the others, and they do have a bit of a dated feel, though that seems intentional to me (so an artistic decision), and some people say poetry becomes dated quickly. (For instance, your poems don't seem to play much with line breaks but break lines only at natural pauses in syntax. You need to break at unexpected places, to make the poem's meanings multiply, to make the poem more indirect in the way it makes its points.) What I see as the weakness of these poems is what was weakest about your other poem: that they tell us what they're going to say. It's usually best for a poem to show rather than say—for it to be.

So here's my crazy writing advice: Read and write a lot. That's it. Read a lot of contemporary poetry, find something you like, and keep reading poetry like that. And write as you do all of this reading. You'll be influenced by what you write, and the process of writing will cause you to think of new ways to do things, things only you can do.

If I were going to give you another piece of advice, I'd say, allow your mind to wander as you write a poem. Your poems are so centrally about making one specific point, but it's better if they're more expansive, which makes them more surprising and alluring. I see that you like description, which is fine, but don't focus so much on producing a poem about something; allow the poem to become something unexpected. I think a recent poem of mine has a few overlaps with poems of yours: it focuses on my perception and records those perceptions, and it focuses on the natural world. So take a look at it here:

http://365ltrs.blogspot.com/2011/02/275-notes-before-sleep.html

Note that it's not of a piece, not a single thing, but the accumulation of perceptions into an experience. A poem should be an experience more than it is the replication of an experience, and I think this poem can give you some hints on how to do this. Still, this poem of mine is not particularly strong itself, and only a first draft, but I think you need to create a freer way to work, one that will allow you to wander. You've proved in that last poem of yours that you do have an ear that you can use and an imagination you can put to work, but you need to free both of them.

As for the other two poems I'd suggest you'd submit, I'd go with "1" and "2," but I'd suggest you spend a night (or a day) working on these, freeing them from the strictures of their didacticism (which is another fault or feature of many of my own poems) and their replication of experience. I think you can do this. And I'd suggest that the change include changing the titles which tell us too much too directly.

And think of fragmentary ways of writing your poems, which is something I see you're working on in some of your recent poems. Here's, for instance, a possible rewriting I did of your poem "2." Note that it's so different that it probably isn't recognizable to you, but revisions like this can free the mind.

I have just dashed this off using images from your poem, paring everything back beyond the essentials, removing punctuation so that linebreaks are the only punctuation but they punctuate against the syntax of the poem. Also the poem is fragmented so that one concept (which may've been a sentence) flows into the next in media res, so that the "story" of the poem is unclear, so that the stone and the person thinking of the stone are merged grammatically, so the story is not a water running narrative but a series of almost unrelated drops. The last line, which is really part of the major point of your poem, is one that makes me a little uncomfortable, because it's so direct, but I've made it a bit more ambiguous, by doubling its meaning.

Note that this revised poem is filled with me and my ways. It depends on a kind of wordplay: renaming things ("palms" of waves), using words in unexpected ways ("denting"), and punning ("stone rocking"). This kind of verbal playfulness is just my way, so I don't think this revision is anything for you, but you need to practice enough to know, naturally, even unconsciously (as if breathing), how you must write, and how it is that your poems must say. Not "what" they must say. "What" is unimportant. "What" is about recreating experiences of yours. "How" is important. "How" is about creating experiences through your poems, about making your poems into experiences. It is better to be something than to replicate something.

Note that my poem is about sound. Listen to it. And make sure you listen to your poems too. Your ear will do wonders for you once you focus on it instead of on the "what" of your poem.

And please note that I'm not claiming this poem of mine is a good poem. It's just a teaching aid.

I hope these thoughts of mine help you. And thanks for being a poet, for being a person of words. So please be the poet you are, not me, not anyone else. But teach yourself how to be the best poet you are.

ecr. l'inf.

76. How

I hope these words help you a little. It's good you're a poet because it's good to have poets around us, so I'll suggest below a few things you can work on in your poetry.

That last poem you sent me is definitely your best. I've read through the others, and they do have a bit of a dated feel, though that seems intentional to me (so an artistic decision), and some people say poetry becomes dated quickly. (For instance, your poems don't seem to play much with line breaks but break lines only at natural pauses in syntax. You need to break at unexpected places, to make the poem's meanings multiply, to make the poem more indirect in the way it makes its points.) What I see as the weakness of these poems is what was weakest about your other poem: that they tell us what they're going to say. It's usually best for a poem to show rather than say—for it to be.

So here's my crazy writing advice: Read and write a lot. That's it. Read a lot of contemporary poetry, find something you like, and keep reading poetry like that. And write as you do all of this reading. You'll be influenced by what you write, and the process of writing will cause you to think of new ways to do things, things only you can do.

If I were going to give you another piece of advice, I'd say, allow your mind to wander as you write a poem. Your poems are so centrally about making one specific point, but it's better if they're more expansive, which makes them more surprising and alluring. I see that you like description, which is fine, but don't focus so much on producing a poem about something; allow the poem to become something unexpected. I think a recent poem of mine has a few overlaps with poems of yours: it focuses on my perception and records those perceptions, and it focuses on the natural world. So take a look at it here:

http://365ltrs.blogspot.com/2011/02/275-notes-before-sleep.html

Note that it's not of a piece, not a single thing, but the accumulation of perceptions into an experience. A poem should be an experience more than it is the replication of an experience, and I think this poem can give you some hints on how to do this. Still, this poem of mine is not particularly strong itself, and only a first draft, but I think you need to create a freer way to work, one that will allow you to wander. You've proved in that last poem of yours that you do have an ear that you can use and an imagination you can put to work, but you need to free both of them.

As for the other two poems I'd suggest you'd submit, I'd go with "1" and "2," but I'd suggest you spend a night (or a day) working on these, freeing them from the strictures of their didacticism (which is another fault or feature of many of my own poems) and their replication of experience. I think you can do this. And I'd suggest that the change include changing the titles which tell us too much too directly.

And think of fragmentary ways of writing your poems, which is something I see you're working on in some of your recent poems. Here's, for instance, a possible rewriting I did of your poem "2." Note that it's so different that it probably isn't recognizable to you, but revisions like this can free the mind.

Stoned

the perfect flat

smooth and round

stone standing

on my foot on

the shore leaning

from slipping from

my palm across

the palms of

each wave and

denting water

its prints fading

and stone rocking

down into that

I cannot find it

I have just dashed this off using images from your poem, paring everything back beyond the essentials, removing punctuation so that linebreaks are the only punctuation but they punctuate against the syntax of the poem. Also the poem is fragmented so that one concept (which may've been a sentence) flows into the next in media res, so that the "story" of the poem is unclear, so that the stone and the person thinking of the stone are merged grammatically, so the story is not a water running narrative but a series of almost unrelated drops. The last line, which is really part of the major point of your poem, is one that makes me a little uncomfortable, because it's so direct, but I've made it a bit more ambiguous, by doubling its meaning.

Note that this revised poem is filled with me and my ways. It depends on a kind of wordplay: renaming things ("palms" of waves), using words in unexpected ways ("denting"), and punning ("stone rocking"). This kind of verbal playfulness is just my way, so I don't think this revision is anything for you, but you need to practice enough to know, naturally, even unconsciously (as if breathing), how you must write, and how it is that your poems must say. Not "what" they must say. "What" is unimportant. "What" is about recreating experiences of yours. "How" is important. "How" is about creating experiences through your poems, about making your poems into experiences. It is better to be something than to replicate something.

Note that my poem is about sound. Listen to it. And make sure you listen to your poems too. Your ear will do wonders for you once you focus on it instead of on the "what" of your poem.

And please note that I'm not claiming this poem of mine is a good poem. It's just a teaching aid.

I hope these thoughts of mine help you. And thanks for being a poet, for being a person of words. So please be the poet you are, not me, not anyone else. But teach yourself how to be the best poet you are.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on February 25, 2011 20:48