Daniel Coyle's Blog, page 19

December 9, 2011

The 1-Second Method

Just before every performance, whether it's in sports, music, or in the workplace, there's a quiet moment just before the action starts. It's the deep breath before the leap, the moment when all the preparation is finished, and you're waiting to start, and there's nothing on earth you can do.

Just before every performance, whether it's in sports, music, or in the workplace, there's a quiet moment just before the action starts. It's the deep breath before the leap, the moment when all the preparation is finished, and you're waiting to start, and there's nothing on earth you can do.

Or is there?

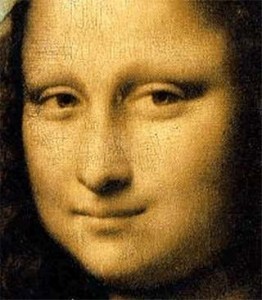

According to some fascinating new research, you should smile.

I know, it sounds like advice from a fifties musical, but in fact it's a useful bit of neuroscience, courtesy of Nobel prize-winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman, author of Thinking, Fast and Slow.

Here's why: our brains are made up of two parallel systems, the Fast and the Slow. The Fast System works by instinct; it's our intuitive autopilot, and used for swift, simple decisions. The Slow System, on the other hand, is for being rational and calculating; it takes more effort to use, and helps us work through complicated problems. Research by Kahneman and his colleagues revealed the systems are activated by, among other factors, our facial expressions.

Here's the freaky part: your expression matters even if you don't feel the underlying emotion. To create a smile, subjects were asked to hold a pencil between their teeth. To create a frown, researchers asked subjects to furrow their brows, which causes the face to take on a natural downturn.In each case, the facial expression drove the resulting behavior; that is, smiling made people behave in swifter, more intuitive ways, while frowning caused them to be more deliberate and rational.

Perhaps there's some deep evolutionary explanation for all this involving expressions and survival. But when I read this, I thought of all the frowning, ultra-serious faces I saw among the practicers in the talent hotbeds I visited — in the book, I wrote that their expressions that resembled Clint Eastwood. Considering this research, perhaps that makes sense. For practicing, go with the Eastwood face. But in the last second before you perform, it's smarter to go with Julia Roberts.

December 2, 2011

The New Way to Identify Talent: The G Factor

So I recently returned from a London sports-science conference where the discussion revolved around the mystery of talent identification. All over the world, in everything from academics to sports to music, millions of dollars and thousands of hours are being spent on singling out high-potential performers early on. And the plain truth is, most of these talent-ID programs are little better than rolling dice.

So I recently returned from a London sports-science conference where the discussion revolved around the mystery of talent identification. All over the world, in everything from academics to sports to music, millions of dollars and thousands of hours are being spent on singling out high-potential performers early on. And the plain truth is, most of these talent-ID programs are little better than rolling dice.

Take the NFL, for instance, which represents the zenith of talent-identification science. At the pre-draft NFL combine, teams exhaustively test every physical and mental capacity known to science: strength, agility, explosiveness, intelligence. They look at miles of game film. They analyze every piece of available data. And each year, NFL teams manage get it absolutely wrong. In fact, out of the 40 top-rated combine performers over the past four years, only half are still in the league.

A lot of smart people have been thinking about this, and what they've decided is this: the problem not that the measures are wrong. The problem is that measuring performance the wrong way to approach the question.

According to much of this new work, what matters is not current performance, but rather growth potential – what you might call the G-Factor — the complex, multi-faceted qualities that help someone learn and keep on learning, to work past inevitable plateaus; to adapt and be resourceful and keep improving.

Thing is, G-Factor can't be measured with a stopwatch or a tape measure. It's more subtle and complex. Which means that instead of looking at performance, you look for signs, subtle indicators — what a poker player might call tells. In other words, to locate the G-Factor you have to close your eyes, ignore the dazzle of current performance and instead try to detect the presence of a few key characteristics. Sort of like Moneyball, with character traits.

So what are the tells for the G-Factor? Here are two:

One is early ownership. As Marjie Elferink-Gemser's work shows, one pattern of successful athletes happens when they're 13 or so, when they develop a sense of ownership of their training. For the ones who succeed, this age is when they decide that it's not enough to simply be an obedient cog in the development machine — they begin to go farther, reaching beyond the program, deciding for themselves what their workouts will be, augmenting and customizing and addressing their weaknesses on their own.

Another tell is grit. This quality, investigated by the pioneering work of Angela Duckworth, refers to that signature combination of stubbornness, resourcefulness, creativity and adaptability that helps someone make the tough climb toward a longterm goal. Duckworth has come up with a simple questionnaire that measures the responder's grit. It has only 17 questions, and the respondent self-assesses their ability to stick with a project, see a goal to the end, etc. (You can take it online here.)

Duckworth gave her grit test to 1,200 first-year West Point cadets before they began a brutal summer training course called the "Beast Barracks." It turned out that this test (which takes only a few minutes to complete) was eerily accurate at predicting whether or not a cadet succeeded, exceeding the predictions of West Point's exhaustive battery of NFL-combine-esque measures, which included tests of IQ, psychological profile, GPA, and physical fitness. Duckworth's grit test has been applied to other settings – academic ones, including KIPP schools — with similar levels of success. (Here's a good story about grit.)

It's fascinating stuff, in part because it leads so many good questions: what other elements are part of the G Factor? And perhaps most important, is it possible to teach it?

November 29, 2011

A Field Guide to Avoiding Toxic Teachers/Coaches

We've spent a fair amount of time in this space talking about what makes up a great teacher or coach. Today, let's talk about the opposite. The bad ones. The ones who quietly steal your time and energy and prevent you from progressing as well as you could. The ones you want to avoid.

We've spent a fair amount of time in this space talking about what makes up a great teacher or coach. Today, let's talk about the opposite. The bad ones. The ones who quietly steal your time and energy and prevent you from progressing as well as you could. The ones you want to avoid.

Confession: I know about toxic teachers/coaches, because, at various times in my life, I've been one. Both in the classroom (in graduate school, no less) and on the sports field (with my Little League team), I've been in charge of the learning process, and I have proceeded to do what I've since realized was a pretty terrible job. (I'll spare you the details, but let's just say that whenever I run into someone from one of my first classes/teams, I usually begin by apologizing.)

So with that in mind, I'd like to offer this brief, completely unscientific list of traits for which to watch.

1) The Courteous Waiter: This is the kind of person who puts all their efforts and attention into keeping you comfortable and happy. They don't push you to the edges of your ability, but rather keep you in the comfort zone, glossing over any moments of difficulty in favor of a "we'll worry about that later" approach. This kind of person is usually quite likable (think of that really cool teacher you had in high school) and because of that likability, you never learn much (again, think of that really cool teacher you had in high school).

2) The Charismatic Speaker: This is the kind of person who spends all their time talking. Lecturing. Weaving shimmering webs of ideas into the air. They're often quite eloquent and charismatic; listening to them can be great fun. Which is precisely the problem — because in the end, passively listening to someone talk is a really inefficient way to learn. We learn by doing, exploring, discovering for ourselves. By asking questions, interacting, engaging with ideas. (Another reason why Socratic method works so well.)

3) The Remote Ruler: This person spends their time high above the playing field, designing strategies and methods, and rarely descend to interact with the people they're leading. Some good examples of this type of teacher is found in the leadership of bigger organizations, like the NFL and Wall Street, both places where a culture of remoteness can easily take hold. This person often seems quite powerful, but they often end up failing because they overlook the most fundamental source of power: the personal emotional connections to the people they're leading.

Finding the right teacher, coach, or mentor is sort of like test-driving a car. And just as with a car, it pays to lift up the hood. Go for a test drive. Find one who connects with you, who challenges you, and who pushes you past what you thought you could do. You'll go farther.

PS — speaking of good teachers, I'm reading a couple really good books right now: What I Talk About When I Talk About Running, by Haruki Murakami (great on the link between endurance and creativity), and Thinking, Fast and Slow, by Daniel Kahneman, which is great on the relationship between impulsive and rational thinking.

November 17, 2011

What's Your Gadget?

For the past couple weeks, my wife Jen has been asking me if I'm going to write about the goggles. She's asked enough about the goggles, in fact, that it's become a running joke in our house. It's gotten to the point that if you simply blurt out the word "goggles" at unexpected times, you get a big laugh.

For the past couple weeks, my wife Jen has been asking me if I'm going to write about the goggles. She's asked enough about the goggles, in fact, that it's become a running joke in our house. It's gotten to the point that if you simply blurt out the word "goggles" at unexpected times, you get a big laugh.

(Goggles!)

So here's the story: there's this eight-year-old kid, Seth Wilson, who lives near us in Ohio. Seth happens to have been named the top-ranked second-grader in the country by a basketball website middleschoolelite.com (why in the world people would rank second graders is a topic for another day). Thing is, Seth is really, really good, and he sometimes practices wearing these homemade — you guessed it — goggles. They're not normal goggles, because the lower half of the lenses is painted black. When Seth wears them during his drills, he can't see anything at his feet.

The goggles increase his feel for the ball, his vision, his touch. Essentially, they nudge him to the sweet spot on the edge of his ability and put the focus on perhaps the most important skill a young player has to develop — controlling the ball on auto-pilot while focusing his attention on the game.

Jen is absolutely right to love the goggles, because they're genius. In a world where people pay big money for lessons and high-tech equipment, a homemade gadget like this is skill-development gold. Which got us thinking about other gadgets.

Such as the Hershey's Kiss, used by young violinists. This gets placed in on the body of the violin as they play. If you lose proper position, the violin tilts and the kiss falls. Keep form, and you earn a treat.

Or the yogurt lids — a hitting-improvement gadget pioneered by the late legendary baseball coach Marvin "Towny" Townsend of Tidewater Little League in Virginia Beach, VA. The yogurt lids are used in the place of balls; the "pitcher" stands a few feet away and flips the lids at the waiting batter frisbee-style; they have to hit a small, curving, speeding object. Because they're plastic lids, you can have batting practice indoors, in a tiny space, and make a lot more swings to boot.

These kinds of gadgets — inexpensive, simple, innovative — can have more effect on learning than a raft of fancy theories or classes. I also like them because of the larger message: good practice methods aren't something that's handed down from on high — they're something you invent, figure out with what's at hand, or borrow from others.

So the question is, what's your gadget?

November 14, 2011

Tip: When to Think (and When Not To)

Readers of this blog know that we're hu-uuuge fans of stealing — by which I mean the kind of stealing where you shamelessly pickpocket good ideas from one line of work (sports, music, business, whatever) and put them to use in another. Here's one, which I especially like. It's stolen from Annika Sorenstam, the golfer, but it could apply to pretty much anybody.

Readers of this blog know that we're hu-uuuge fans of stealing — by which I mean the kind of stealing where you shamelessly pickpocket good ideas from one line of work (sports, music, business, whatever) and put them to use in another. Here's one, which I especially like. It's stolen from Annika Sorenstam, the golfer, but it could apply to pretty much anybody.

Here it is: Draw an imaginary line that separates your practice space from your performance space. When you're inside the Practice Zone, your brain is fully switched on. You're thinking, strategizing, planning. But when you step across the line into the Performance Zone, you click off your mind and just play.

Here's how Sandy Williams, a reader who recently attended one of Sorenstam's camps, describes her using it:

Essentially she drew an imaginary line about a yard behind the ball (think of the back line of a batters box). She deemed the area behind the line as the 'thinking' zone and the area in front of the line as the 'play" zone. In the thinking zone, she would get info from her caddy and think hard about the wind, the aim, which club, which shot, visualization, etc. Then once she had figured out what she wanted to she crossed the line into the 'play' zone, she said she turned her mind off and hit the shot (or 'played' like she was a little kid) like she had done millions of times before.

There's plenty of brain science that supports this method (MRI scans show that the more skilled an athlete is, the less they're thinking). And of course we know that top performance happens when we relax and go on autopilot, letting our unconscious brain do its magic. But I like it because this Practice/Play Zone idea could be applied to lots of stuff beyond sports. Music, writing, trading stocks, chess, you name it. We all have a zone where we build, and then a zone where we relax and show what we've built.

I also like it because it shows the real paradox at the heart of improvement. During practice, thinking and planning are your friends. During performance, however, thinking and planning are your enemies. You can't avoid this paradox; you need to build a routine that embraces both sides. You essentially have two brains, the conscious and unconscious; so the best way to improve is to give one zone to each.

PS — Thanks to Sandy Williams and the always-enlightening Finn Gunderson, director of alpine education for the U.S. Ski Association and director of sports education at YSC Sports, for passing this one along.

PPS — What other strategies have you come across that address the practice/performance issue?

November 8, 2011

A Word of Coaching Advice: Talk Less, Matter More

Take one second and think about the best teacher, coach, or mentor you ever had.

Now come up with one memory of them, fast.

(Got it?)

What's your memory? Is it something your coach/teacher/mentor said? Something they did?

Perhaps what you remembered wasn't anything particular they said or did, but just their face — specifically their eyes, and how those eyes looked at you — or, rather, looked into you. Which is to say: the lasting impact of our teachers might not be contained in their words, but in the connections they form with us.

When you look around today, a lot of coaches and teachers and bosses seem to be doing everything but connecting. Go to a soccer game, for instance, and you tend to see coaches on the sideline doing a lot of talking (shouting out mid-game advice, orchestrating the action), but not a lot of connecting. Certain CEOs and managers are similar, though perform do their sideline orchestrating via email. But is this wise? Is it useful?

I recently met a terrific soccer coach by the name of Iain Munro, who coaches at YSC Sports Academy in Philadelphia (a burgeoning soccer hotbed in its own right). Munro, who's in his sixties, played and coached at the top level in England and his native Scotland (working with, among others, Alex Ferguson and Jock Stein). I put the question to Munro this way: if the average coach says 100 words to his players, how many words should a master coach say?

Munro looked into my eyes; he let me know he really heard the question and was giving it due consideration. He placed a friendly hand on my shoulder, and I got an ineffable feeling that I was about to hear something important. Then I did.

"Ten words," he said. "Fewer, if possible."

The truth is, great coaches and teachers don't spend their time talking. They spend most of their time watching and listening. And when they communicate, they don't just start talking. First they connect on an emotional level, to one individual at a time. They deliver concise, useful information, and they make that information stick. Kind of like Munro did when he communicated with me.

So with that in mind I'd like to offer the following checklist; a filter to use before you start talking.

1. Are you connected? Do you have the person's complete and undivided attention?

2. Do you know — deeply understand — where that person is in their development right now, and what the next step is?

3. Can you, in five seconds or less, deliver a clear, memorable piece of useful information to help them take that step?

Watch Munro work with his soccer teams and you'll see him sidle up to a player during a drill, without interrupting the larger flow. He puts the hand on their shoulder, connects to them, and delivers a nugget of helpful information. Then he steps away, allowing the player to take that nugget and start applying it.

Munro's players, of course, will remember him for the rest of their lives. Not because he makes them better (which he does) or because he's so entertaining (which he is, too) but for the same reason you remember your greatest coach: because he's not about himself, he's really about the people he's trying to help.

November 2, 2011

Genes are Overrated

Most everybody can roll their tongue in a tube. But have you ever tried the cloverleaf? It's hard. Super hard, in fact. When you first try it, you flounder around and can't even come close.

Back when I was in fifth grade and again when I was in college biology class, my teachers informed me that tongue-rolling, like so many other talents, is genetic. They said around 80 percent of people have the gene to roll their tongues in a tube shape. A far smaller percentage — a genetically chosen few — could fold their tongues into the rare cloverleaf.

But a funny thing happened the other day. I was driving my daughter Katie to school and she stuck out her tongue at me and said, "Look! I can do it!"

I look over, and sure enough, she's folded her tongue into a cloverleaf shape. It's kinda freaky, but kinda cool too.

I'm not saying our family is weird or anything, but Katie is officially the third Coyle kid to be able to perform this feat. Also, I'm told that several of their friends can do it, too. So what's up with all these cloverleaf experts? It must be the genes, right?

Thinking about this got me thinking about when I was in 8th grade. One day a new kid arrived in school. His name was Bob Audette, and he had just moved to Anchorage from far-off New York. To us, he might've moved from the moon. Bob Audette was different from anybody any of us kids had ever met. Bob Audette wore cooler clothes than we did. Bob Audette spoke in a thick accent that sounded exactly like Vinnie Barbarino on "Welcome Back Kotter." Bob Audette called the water fountain "the bubbler." Coolest of all, Bob Audette carried a basketball everywhere he went, and he would sometimes flip the ball into the air and spin it on his finger with supreme Vinnie Barbarino casualness, the ball revolving there while he chatted up the girls in the hallway. It was magic.

This had a strange effect on me. After watching Bob Audette for a few days, I found myself taking a basketball and trying to spin it on my finger. I didn't play basketball — this skill was completely useless — but for whatever reason I got obsessed, spending hours in my basement spinning this ball. Of course, I was terrible at it for a long time. But then, all of a sudden, I wasn't terrible. In fact, I could do it as well as Bob Audette. (On all other fronts, I remained a lot closer to Horshack than Vinnie Barbarino, but hey, it was something.)

I asked my daughters about the cloverleaf trick, and they reminded me who had started this whole thing: it had been Mitchell Black, from Brooklyn. Mitchell, 11, had visited us in Alaska a few years ago with his parents. He was a city kid, smart and funny and personable, and he'd shown us his trick. Our girls had stared in amazement. They started trying it, mimicking him, competing with each other. Next thing you know, a whole bloom of cloverleaves has started.

Genes are so overrated.

(And the power of Mitchell Black and Bob Audette is so underrated.)

October 26, 2011

Brainology for All! A Bill of Kid Rights

One proven way to improve our lives is to use the What-Will-the-Grandkids-Chuckle-About Method. This method involves asking yourself a simple question: what are you doing right now that your grandkids will see as laughably ass-backward 50 years from now?

One proven way to improve our lives is to use the What-Will-the-Grandkids-Chuckle-About Method. This method involves asking yourself a simple question: what are you doing right now that your grandkids will see as laughably ass-backward 50 years from now?

For example, we look back to the early sixties and see societal habits that seem, in retrospect, comically short-sighted — habits like sexism, the way they ate, smoked, drank, drove (usually at the same time).

So what will your grandkids be chuckling about in 2061?

Here's my answer: Brain Ed.

I think our grandkids will look back and say, Back in 2011, parents and teachers wanted kids to learn, but somehow they didn't bother teaching kids the most important part — how the learning machine actually works. What the heck were those people thinking?

And our grandkids will be absolutely, positively, 100-percent right.

Right now, teachers, parents, and coaches in our society focus their attention on teaching the material — whether it's algebra, soccer, or music. This is the equivalent of trying to train athletes without informing them that muscles exist. It's like teaching nutrition without mentioning vegetables or vitamins. We feverishly cram our classrooms with whiz-bang technology, but fail to teach the kids how their own circuits are built to operate.

It's all completely understandable, of course. Our parenting and teaching practices evolved in an industrial age, when we presumed potential was innate, brains were fixed (just as we presumed smoking was healthy and three-martini lunches were normal). But that doesn't make it right. In fact, you could argue that teaching a child how their brain works is not just an educational strategy — it's closer to a human right.

So as long as we're on a soapbox, let's take this all the way and make it official.

The New Bill of Kid Rights:

1. Every child has the right to know how their brain grows

2. Every child has the right to a teacher who understands how skill develops

3. Every child has the right to an environment that's aligned with the way skills grow in the brain

(Anything we need to add to that?)

Here's a suggestion: teach brain-ed in schools. Why not devote a chunk of time, especially at the start of the school year, to teaching how the brain grows when it learns. To teaching how repetition builds speed and fluency. To helping kids to understand and experience the biological truth that struggle makes you smarter, that the brain grows when challenged.

Some progressive schools are already doing this. Last week I visited Castilleja School in Palo Alto (just down the street from Steve Jobs's house, naturally) where they're offering a new class called "Brainology" for seventh graders. In it, students learn how the brain is built to grow. They try out different studying strategies. They learn that the brain functions like a muscle: no pain, no gain.

Even small exposures can have a big impact. Stanford's Carol Dweck did an experiment where she divided 700 low-achieving middle schoolers into two groups. Both were given an eight-week workshop on study skills, and one group received a 50-minute session that described how the brain grows when it's challenged. (The other group's session learned about generic science.) In a few months, the group that had learned about the brain had improved their grades and study habits to the point that teachers, without knowing, could accurately identify which student had been in which group.

It's not rocket science. In fact, it's easy, because it pays massive dividends. Plus, it gives our grandkids one less thing to chortle about.

October 10, 2011

Forget 10,000 Hours. Try Hans's 2-Minute Method.

By now, most of you have heard of the Rule of 10,000 Hours, the finding that most world-class experts have spent a minimum of 10,000 hours intensively practicing their craft.

By now, most of you have heard of the Rule of 10,000 Hours, the finding that most world-class experts have spent a minimum of 10,000 hours intensively practicing their craft.

Likewise, many of you are probably familiar with the sensation known as the Rule of 10,000 Hours Wince. This occurs where you realize (whoa!) just how intimidatingly far you still have to go.

Counting hours is a bad idea. Not only because it's difficult to accurately measure quality practice (the original studies have created a worthy debate, seen here), but also because it tends to lead us toward a royal bummer of a mindset. Developing talent is about enthusiasm and energy. Counting hours can turn us into drudges, marking our tally like a doomed prisoner marking the days on the cell wall. Besides, most of us aren't trying to become world-class — we're just trying to be better tomorrow than we are today. What to do?

One good idea was recently offered by one of my favorite people. His name is Hans Jensen, and he's one of the world's best music teachers (here's his website). Hans looks exactly like you'd expect a mad scientist to look, if the mad scientist taught cello and liked to run marathons. His hair is always a little disheveled; his eyes are always wide open, and his mind is always churning with new ideas. Here's his latest: I call it Hans's 2-Minute Method.

It works like this:

Pick a specified target you want to perfect. It needs to be small and definable — a chunk, in the parlance. If it's a tennis serve, target just the toss. If it's a song, target just the toughest ten seconds. If it's public speaking, target just the introduction.

Pick a time of day. (Morning works best.)

Be alone. This isn't about a teacher or coach telling you what to do — it's about you doing it, by yourself.

Work as urgently and intensively as humanly possible on that target skill for two minutes.

Stop. Walk away. And tomorrow, do it again.

This technique originated with one of Jensen's students who was strapped for time, but who wanted to learn a complicated etude. "We were shocked at how well it went," Jensen said. "The key was total focus and being ruthless about noticing and fixing every tiny mistake from the start."

Why does it work?

It forces you to prioritize and strategize — to look critically at your skill and pick the elements that matter most.

It eliminates the sloppiness that often marks shallow practice.

It creates a daily habit.

It increases intensity. It's hard to practice with 100 percent intensity for an hour. But for two minutes? That's achievable.

I also like the 2-Minute Practice because it nudges us toward counting things that matter. Learning is a construction process. It's possible to get a lot done in a short amount of time, because in the end, it's not really about time — it's about making intense, high-quality reaches toward a target.

This also makes me wonder — what other techniques might work like this? How else are you improving the quality of each minute? I'd love to hear about your mad-scientist experiments.

September 28, 2011

What's Your Z-Score?

And we're back! We had a good summer in Alaska (thanks for asking!) and now, as is our family's migratory pattern, we're now back in Ohio for the school year.

It's kinda wild, shuttling back and forth from smalltown Alaska to the Ohio suburbs. It takes a few days to get acclimated, to get used to heat, the sight of neatly trimmed hedges, the tootling of the ice-cream trucks. Then — voila! — we figure out where we're at.

I've been thinking about that question — figuring out where you're at — and I recently bumped into a useful tool. It's called a Z-Score, and it looks like this:

The Z-Score is a method used by Red Bull Sports to train their athletes. Red Bull sponsors a bunch of the world's top surfers, skateboarders, and extreme-sport types, and trains them in crazy-nice facilities around the world — and does a brilliant job of it, I might add. The above Z-Score is for a pro skateboarder, but this method can be applied to any talent, and any person.

Step 1: take a sheet of graph paper.

Step 2: Around the margin of that graph paper, write down the four or five specific skills you want to develop. For example, if you happened to be a doctor, you might select JUDGEMENT, PERCEPTION, TECHNICAL KNOWLEDGE, and BEDSIDE MANNER. On the other hand, if you happened to be in sales, you might select ABILITY TO CONNECT, PRODUCT KNOWLEDGE, ABILITY TO DELIVER PITCH, etc. The key is to be as specific as possible.

Step 3: Grade yourself on each of these skills by placing a dot on the graph paper. If you're 100 percent perfect, the dot should touch the word. Be brutally honest. (To do this more precisely, start from an X in the center of the paper, rate yourself from 1-10 in each skill, and use the squares of the graph paper to measure outward toward the target skill.)

Step 4: Now connect the dots and draw the resulting shape. That spiderweb shape is you. To be more precise, that's your map — both where you are now, and where you want to go. The idea is to build your practice sessions targeting those skills; the goal is to push your Z-shape outward as far as you can.

I'll add one idea to the Z-Score: when you select each target skill, also select a target person for that skill — someone who embodies that skils, who performs that one narrow thing better than anybody you've ever seen. That way, you're not striving toward some abstraction, but toward a flesh-and-blood person.

Speaking of reaching goals, I've got some terrific news to share. Two years ago, after reading a certain book (okay, mine) Michael Reddick set out to become a professional billiard player. Last week, he won the Northern California round of the U.S. Amateur Championship and, on the weekend of November 4, will head to Florida and try to become national champ. Check out his blog documenting his journey. Good luck, Michael; we'll all be rooting for you.