Daniel Coyle's Blog, page 21

January 1, 2011

Got Passion? The Quiz

What's life's single most important question?

What's life's single most important question?

There are many perfectly worthy ones — questions about family, relationships, work, love — but when it comes to charting our futures, one question rises above the rest.

What's your passion?

Yes, it's a cliche. But it also happens to be irrefutably true. Passion — that primal, unreasoning, uncontrollable enthusiasm that links our identities with a distant goal — forms the emotional foundation for all excellence, no matter who you are. Science shows that passion functions in our brains like rocket fuel; with it, progress is swift and exhilarating. Without it, progress is slow and tedious.

So the question before us is not whether passion is important. The big question is, how do we know when we've got it? Life is a series of crossroads and decisions: how do we choose what path to pursue? How do we tell the difference between our casual enjoyments and our true, lasting passions?

One logical way might be to look at case studies of successful, passionate people — since they located their passion; perhaps we can learn from their process and apply their insights.

Yet when we ask those successful, passionate people how they found their passion, we get a surprising result: most of them have no idea. In fact, the smarter and more successful they are, the dumber they sound when they talk about it.

For example, here's Warren Buffett on how he discovered his passion for investing.

"From a young age, I always was interested in money, and how to make it."

And here's Wayne Gretzky on how he discovered his passion for hockey.

"I liked playing hockey. I'd play all the time."

Not exactly insightful stuff, is it?

But I don't think Gretzky and Buffett are being falsely modest or evasive. Rather, I think it's because they genuinely don't know. Passion occurs largely in our unconscious mind. It sneaks up on us. It isn't like an inborn trait so much as it is like a virus — infecting us without us knowing, directing our primal thoughts and emotions, taking over our emotional lives. Asking a successful person how they got passionate is like asking someone how they caught the flu. They don't know because they can't know. One day they didn't have it. The next day — wham! — they do.

What would be useful for most of us, I think, is some kind of passion-detector. Some tool that we can use to know when our fires are being lit; a thermometer that gives the early warning signs of a passion infection

So while we wait for neurologists to build such a device, I'd like to offer the following brief quiz. It's a completely unscientific list of questions based on my experiences visiting talent hotbeds (where the passion virus tends to be epidemic) as well as ideas cribbed from motivational psychologists like Carol Dweck and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi.

It works like this: put your potential passion in the place of X. In each paired statement, choose whether you agree more with (A) or (B). (Of course, putting "sex" or "eating chocolate" in place of X will work fine, just as it should.)

1.

A) X gives me a feeling of euphoric happiness

B) X gives me a feeling of euphoric happiness plus a deep fascination. I find myself wanting to look deeper. I want to figure out how it's done.

2.

A) I think about X a lot.

B) I cannot not think/talk/dream about X. My friends and family think I'm a bit nuts.

3.

A) X provides me with enjoyable payoffs — like recognition and pride.

B) I would do X for free, even if nobody were watching.

4.

A) When I'm doing X, I'm happy and engaged.

B) When I'm doing X, it's as if I'm in a private world. Time flies.

Scoring: If you answered (A) to most questions, you have a mild case of passion for X. If you answered (B), on the other hand, then you might have a serious passion infection. Choose your path accordingly.

Big thanks to all you readers for your great comments and questions — I appreciate every bit of it. Here's to a great 2011!

December 2, 2010

Unknown Genius Teachers: Who's Yours?

At first glance, our culture seems good at celebrating great teachers. We talk endlessly about how important they are. We give out Teacher of the Year awards. We watch them onscreen — the Dead Poet Society guy, the Stand and Deliver guy, the To Sir With Love guy, the teacher in "Glee." They're heroes.

At first glance, our culture seems good at celebrating great teachers. We talk endlessly about how important they are. We give out Teacher of the Year awards. We watch them onscreen — the Dead Poet Society guy, the Stand and Deliver guy, the To Sir With Love guy, the teacher in "Glee." They're heroes.

But what about in everyday life? Do we have ways of locating and celebrating heroic teachers? Are there ways of identifying unknown geniuses?

Take Cosimo De Pietto, choir teacher in Brooklyn's Erasmus High School in the 1950s, for example. Now, I can say with absolute certainty that you've never heard of Cosimo De Pietto. De Pietto was a terrific choir teacher by all accounts – he was tough, he was inspiring, he led many to a career in music.

The most interesting thing about De Pietto is that one of his choirs contained two students named Barbra Streisand and Neil Diamond (how's that for a powerhouse chorus, Gleeks?). Both Diamond and Streisand credit Mr. De Pietto for helping to form their passion for music. (Though, as Streisand points out, De Pietto never let her solo.)

It's a remarkable story – two world superstars from the same small high-school choir. Turned onto music by the same man, taught the basics by the same man, guided by the same man. You would have to work hard to find another person who affected American music as profoundly as Cosimo De Pietto.

With that in mind, let's measure how modern culture appreciates Mr. De Pietto:

Total Google hits for "Barbra Streisand" and "Neil Diamond" = 22,000,000

Total Google hits for "Cosimo De Pietto" = 136

I don't know about you, but I think these numbers are out of whack. I think there should be a way to recognize and pay tribute to the best unknown master teachers.

So here's the deal: you nominate the best unknown genius teachers or coaches of all time, provide a short biography, and I'll start keeping a list.

Ground rules for nominations:

1) Be specific

2) Keep them short

To get things going, here are a couple:

Marvin "Towny" Townsend: Started two youth baseball teams in Tidewater, VA, that produced five major-league ballplayers; invented revolutionary new techniques to teach the art of hitting using yogurt lids.

Jim Steen: Swim coach at Kenyon College; his swimmers have won 47 NCAA titles; nicknamed The Stroke Whisperer. Quote: "The road to success has no neon signs to herald your arrival."

Who else belongs on this list?

November 17, 2010

How to Light a Fire: The Keith Richards Method

Passion is the nuclear reaction at the core of every talent. It's the glowing, inexhaustible energy source. It's also pretty darn mysterious.

Where does intense passion come from? How does it start, and how is it sustained? How does someone fall wildly in love with math or music, stock trading or figure skating?

Most of us intuitively think of passion as uncontrollable — you have it or you don't, period. In this way of thinking, passion is like a lightning strike, or a winning lottery ticket. It happens to the few, and the rest of us are out of luck.

But is that true? Or are there smart ways to increase the odds?

We get some insight into that question from none other than Keith Richards, whose book Life just came out. My favorite part of the book (and that's saying something) is the part where Keith tells how he fell in love with music, and specifically with the guitar. The process went like this:

Step one: Keith's Grandpa Gus, who was a former musician and a bit of a rebel, noticed that Keith liked singing.

Step two: whenever young Keith would come over, Gus placed a guitar on on top of the the family piano. Keith noticed. Gus told him, when he was taller, he could give it a try.

Step three: one momentous and unforgettable day, Gus took the guitar down from the piano, and handed it to Keith. From that moment, Richards was hooked (his first addiction). He took the guitar everywhere he went.

As Richards writes:

"The guitar was totally out of reach. It was something you looked at, thought about, but never got your hands on. I'll never forget the guitar on top of his upright piano every time I'd go and visit, starting maybe from the age of five. I thought that was where the thing lived. I thought it was always there. And I just kept looking at it, and he didn't say anything, and a few years later I was still looking at it. "Hey, when you get tall enough, you can have a go at it," he said. I didn't find out until after he was dead that he only brought that out and put it up there when he knew I was coming to visit. So I was being teased in a way."

Reading it, I couldn't help but think that most parents and teachers — me included — do precisely the opposite. We don't put things out of reach — in fact we put them within reach. We go fast, not slow. We try to identify passion, not to grow it. We don't take the time to make the nuclear reaction happen on its own.

For me, the lessons are these:

Don't treat passion like lightning. Treat it like a virus, one that's transmitted on contact with people who already have it. Grandpa Gus loved music. He noticed Keith liked singing.

Create a space for private contact with a vast, magical world. The guitar was totally out of reach. It was something you looked at, thought about, but never got your hands on.

Give time for the ideas to grow. And I just kept looking at it, and he didn't say anything, and a few years later I was still looking at it.

Know that it's never about today, but rather about creating a vision of the future self. "When you get tall enough you can have a go at it."

For parents and teachers, Gus provides a useful model. Because Gus didn't hover. He didn't push. He didn't even try to teach, beyond some rudimentary chords. But he did something far more intelligent and powerful. He understood what makes kids care. He carefully put the elements in place, sent a few pointed signals at the right time, and let the forces of nature take their course.

Smart man, that Gus.

And I can't help but wonder: are there other Gus stories out there that might be instructive? How do we take the Gus Method and apply it to schools, or sports, or math?

PS — Thanks to all you readers who requested Spanish editions — they're being mailed today. Venga!

November 3, 2010

How NOT to Develop Your Talent: The 3 Deadly Habits

We spend a healthy amount of time here trying to identify good habits for building skill. In fact, we do it so much that I can't help but wonder: what if we turned the question on its head? What if we tried to identify the worst, most unproductive, most deadly habits? What habits are skill-killers? What's the fastest way to slow down your talent development?

Let's start with a well-established truth: many top performers are obsessive about critically reviewing their performances – either on videotape or with a coach or teacher.

A good example of this is Bill Robertie, who's a world-class poker player, world champ in backgammon, and a grand master in chess (and who's written about by Alina Tugend in her soon-to-be-released book Better by Mistake). Robertie reviews every game obsessively—even the ones he wins—searching for tiny mistakes, critiquing his decisions, breaking it down. The same is true of many top athletes, musicians, comedians, and (I can vouch) writers.

Which leads us to Deadly Habit #1: Thou Shalt Ignore Your Mistakes.

In order to develop your talent slowly, you should never, ever review your performance. You should regard errors as unfortunate, unavoidable events, and do your best to immediately hide their existence or, even better, erase them from your memory.

Another general truth about top performers is that they love rituals. Whether Rafael Nadal prepping for a serve or Yo-Yo Ma prepping a sonata, a lot of top performers are addicted to idiosyncratic, persnickety rituals that seem, to the neutral observer, insanely detailed and RainMan-esque. They tie their sneakers just so, they place their violin case at a certain precise angle. These behaviors are usually described as a superstition, but I think that misses the point: their ritual is their unique way of prepping themselves to deliver a performance.

Which brings us to Deadly Habit #2: Thou Shalt Avoid Ritual.

In order to develop your talent slowly, you should approach each practice and performance as if you've never, ever done it before. You should be casual. You should avoid any repetition of actions, thoughts, or patterns of any kind, and instead make every day completely different.

A third commonality of top performers is that they are thieves. They are incurable shoplifters of ideas and techniques, constantly scanning the landscape for something they can use. As Picasso said, "Good artists copy. Great artists steal."

Which gives us Deadly Habit #3: Thou Shalt Not Steal.

In order to develop your talent slowly, you should regard your talent as your own private creation, and your challenges as private challenges that only you can solve. Don't look elsewhere for guidance; certainly not to other performers.

It's interesting to note that each of these deadly habits is not a big thing. They are small, nearly innocuous-seeming patterns that we can all fall into. We've all ignored past mistakes, avoided ritual, and failed to find guidance in the experiences of others. But here's the real point: perhaps these little habits are a lot bigger than we might think.

This point is underlined by a fascinating paper I just bumped into called The Mundanity of Excellence, by Daniel Chambliss. Chambliss makes a powerful case that top performers aren't great because of any overarching superiority, but rather because they do a lot of ordinary things very well. They pay attention to detail. They make each repetition count. They seek small, incremental improvements one at a time, every single day. And these little habits, over time, add up to great performance.

As Olympic gold-medalist swimmer Mary T. Meagher puts it, "People don't know how ordinary success is."

Of course, these three habits aren't the only ones. What other deadly habits are out there? I'd love to hear your suggestions.

October 20, 2010

Advice That Changed Your Life

When it comes to developing our talents, we all hear a lot of good advice. In fact, there's never been a moment in the history of the world when we've had such an incredible bounty of good advice – a teeming ocean of it, provided by teachers, coaches, parents, the Internet.

When it comes to developing our talents, we all hear a lot of good advice. In fact, there's never been a moment in the history of the world when we've had such an incredible bounty of good advice – a teeming ocean of it, provided by teachers, coaches, parents, the Internet.

For example, pick up a golf magazine. Each page brims with dozens of perfectly sound, smart tips; it's a cornucopia of good advice. But does all that good advice actually make you better? (Judging by the historical average of golf scores, the answer is a resounding no.) It's the same with other sports, music, art, math, business, you name it.

This surplus creates a uniquely modern problem: with good advice so plentiful, how do you know when you've located truly great advice – the rare, powerful ideas that really matter? How do you know when you've found advice that might change your life?

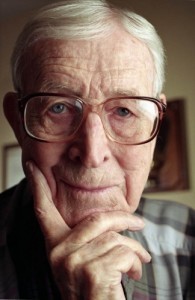

For instance, here's one of the the greatest pieces of advice I've heard. It's from the late John Wooden, and it goes like this: You haven't taught until they've learned.

That's it.

You haven't taught…until they've learned.

I know what you're thinking. Because I thought it when I read it for the first time a few years back. My thought was, no kidding, dude.

But then one day shortly afterward I was coaching my Little League team, trying to teach them to field grounders. I was, as usual, putting my attention into my coaching – saying the correct words, showing them the correct form – and presuming if they picked it up, that was their responsibility.

Wooden's words hit me like an avalanche. I wasn't really coaching, because they hadn't learned it yet. I wasn't teaching, I was just talking. And no matter how wisely I talked, no matter how brilliantly the drills were designed, it didn't matter until they actually learned it. That was the only yardstick.

His advice showed me that it really wasn't about me at all—it was 100 percent about them, about doing whatever it takes to create a situation where they learned. It seems strange to say now, but that was a titanic realization, and I still find myself thinking about it a lot.

I think this kind of advice–truly great advice–tends to follow a distinctive pattern.

It seems super-obvious at first, then gets deeper as you live with it.

It expresses a basic scientific truth about learning.

It jolts your perspective and leaves you somewhere new.

And so here's the next step: I think it would be good and useful to start to gather some of these jewels of great advice in one place. Namely here, on this blog.

What's the single greatest piece of advice you've ever heard? What's the one that changed your life? It could be anything – something you heard or read or saw – all that matters is that it works for you.

You can write them in the comments section below, or email them to me at djcoyle@thetalentcode.com and I'll start a master list to use and share.

To get things going, here are a few gathered from a peanut gallery of friends:

–Practice on the days that you eat

–If you want to get better, double your failure rate

–Do one thing every day that scares you

PS – Does anybody know of someone who could use Spanish-language copies of The Talent Code — or, as it's titled, El Código de Talento? I've got a couple dozen, and would be happy to send them to a good home. Bueno.

October 6, 2010

How to Be More Creative (Step 1: Destroy)

When we think about creative people, we usually think of people who can produce something brilliant and amazing out of thin air. The kind who are, as the saying goes, naturally creative.

When we think about creative people, we usually think of people who can produce something brilliant and amazing out of thin air. The kind who are, as the saying goes, naturally creative.

But here's a strange pattern: when you look more closely at the daily habits of super-creative people, they are doing exactly the opposite. They're not creating out of thin air. Rather, they are creating, then destroying, then creating again. It's not one step. It's three.

A few examples.

Jon Stewart. This recent profile provided a vivid X-ray into a typical day. In the morning Stewart and staff write the script for The Daily Show. Then, a couple of hours before taping, "Stewart and his team go on a nonstop, rapid-fire jag that tears up and rewrites nearly three-quarters of the script." Then those new ideas are discarded and replaced by better ones. They keep churning until air time, throwing away a huge percentage of what they create.

Great charter-school teachers. When Doug Lemov set out to study the habits of top teachers for his Teach Like a Champion , he found a strange pattern: when he asked about their lesson plans, the best teachers said they didn't have any lesson plans right now, because they were in the midst of ripping up and rewriting the whole program. This wasn't an exception or a fluke; Lemov gradually realized: it was a telltale sign that they were high-quality teachers.

U2. A few hours before the kickoff of their stadium tour in Chicago last year, Bono hijacked the dress rehearsal and completely reshaped a 14-year-old song – even writing new lyrics and melodies. The session ended with drummer Larry Mullen wisecracking a sentence that could be the a motto of this approach: "If it ain't broke, break it."

The changes that Stewart, Bono, and the teachers are making are not small changes; this could never be called editing or honing. No, this is the equivalent of a skilled carpenter taking the time to build an entire house and then – while the paint is still wet – tearing it down with a bulldozer and building a brand-new house on the foundation. And I'm fascinated by it because I think it takes creativity out of the realm of magic, and into a place we can understand.

The takeaway: To build the good stuff, first you have to build the bad stuff. The bad stuff isn't really bad – it's a step; a blueprint that shows you where we need to go next. Without the bad script, there is no good script; without the crummy lesson plans, there is no great lesson plan.

If you think of creativity the traditional way, this makes zero sense. (Why in the world would creative geniuses consistently produce bad first drafts?) But if you think of creativity as a stepwise process – a literal construction of wires in your brain – then it begins to add up. This process is not about simply being picky or relentless. The early attempts are like probes, exploring the landscape, seeing what works and what doesn't. The later attempts use that information to be more accurate, to deliver a better lyric, or joke, or lesson plan. The bad stuff is not accidental; it's required. If it ain't broke, break it.

So how do we apply this pattern to our lives?

Cultivate the mental habit of circling back, to reconsider things you take for granted.

Have the willingness to chuck what is perfectly good in order to try to try something better. This requires a tolerance we find often in the arts and all too rarely in sports and business, which are more risk-averse. But creativity and innovation are not about being efficient; they're about hitting the mark.

Avoid getting married to one approach. When it comes to ideas, it's always better to play the field.

(Of course, now that I've written this, I can't stop circling back and trying to see where I might tear it apart and replace it with something better. Damn you, Jon Stewart!)

September 21, 2010

The One Best Habit

One of Hemingway's early notebooks

I love looking into the private daily routines of great performers, from da Vinci to Dickens to Dave Matthews. Part of it is pure voyeurism (they eat what for breakfast every day?), but a larger part is to treat their lives as a detective story. What are they doing that helps them perform so well? What clues can we detect?

Most of us instinctively look for Big Clues. Are they tightly disciplined, or do they work only when the spirit moves them? Are they from h...

September 8, 2010

How to Raise a Prodigy (and How Not To)

We love whiz kids. We love pint-size Michelangelos and Michael Jordans who can pull off fast, sophisticated feats of agility and speed at an impossibly young age.

We love whiz kids. We love pint-size Michelangelos and Michael Jordans who can pull off fast, sophisticated feats of agility and speed at an impossibly young age.

But here's a surprising little secret : when you take a hard look at the science, the majority of super-talented whiz kids do not become world-class adult performers. Check here and here for some of the evidence – or consider the mediocre record of those "experts" who evaluate talent for the NFL, MLB, and NBA draft – and whose...

August 24, 2010

Letter to Students: Cliffs Notes for A Faster Brain

Dear Kids,

Happy first day of school! I've got good news and bad news.

First the bad news: You are about to spend hundreds of hours learning a bunch of small, interconnected facts, most of which you will never, ever, ever use again. (Ask your parents how to calculate out the area of a rhombus. I rest my case.)

Now the good news: school is hugely, amazingly, life-changingly worthwhile. Here's why: learning bunches of interconnected facts makes your brain faster and stronger. School is like a...

August 5, 2010

How to Be a Late Bloomer

Late bloomers are underrated.

It's not just the condescending phrase — the whispered implication that they should have bloomed earlier. And it's not the fact that our culture tends to sprinkle the young with the fairy dust of infinite possibility, while treating late bloomers with the grim surprise we give when spotting an escaped farm animal roaming city streets – what are YOU doing here?

No, the real reason they are underrated is that these kinds of second-act successes are more common and p...