Daniel Coyle's Blog, page 15

July 17, 2012

What World-Class Practice Looks Like, Part 2

One of the beautiful things about great practice is how simple it is.

This is especially true with soft skills — those improvisatory skills of reading patterns and reacting instantly to them — which show up so often in team sports and the creative arts.

Check out this video of Barcelona (aka the world’s best soccer team over the past four years) as they do their regular one-touch keep-away workout, which is called rondo.

Here’s what I like about it:

1) It generates reps of the key skills (anticipation, quick, accurate decisions under pressure), over and over.

2) It’s played with 100 percent maximum intensity.

3) It’s really fun/addictive — check out those smiles and laughs at the end.

Xavi, Barca’s midfielder, says: ”It’s all about rondos. Rondo, rondo, rondo. Every. Single. Day. It’s the best exercise there is. You learn responsibility and not to lose the ball. If you lose the ball, you go in the middle. Pum-pum-pum-pum, always one touch. If you go in the middle, it’s humiliating, the rest applaud and laugh at you.”

For this team, rondo isn’t a mere drill. It’s more like their identity.

To me, the truly interesting question is this: How do you create a culture in which this little game — not ego, not showing off, not even scoring goals — becomes the most important and valued part?

July 11, 2012

How the Best Teachers Begin Their Lessons

Quick question for coaches and teachers: What’s the single most important moment of a lesson? Is it:

Quick question for coaches and teachers: What’s the single most important moment of a lesson? Is it:

(A) the initial explanation of the skill being taught?

(B) the first couple tries?

(C) the moment things click, when the learner “gets it”?

I think the answer is (D) — None of the Above.

There’s a strong case to be made that the single most important moment of learning happens before the lesson actually begins.

We know that master coaches are extremely skilled at quickly making a strong emotional connection with a learner, to create the bond of trust that’s the foundation of all learning.

But mere emotional connection isn’t enough. The world is filled with extremely charismatic, fantastically entertaining teachers who are wonderful at creating connection but not so great at actually improving skill.

Because it’s not enough just to capture the learner’s attention — you have to create intention: an urgent desire to work hard toward a concrete goal, toward some vision of their future self.

Science is giving us a peek inside that process. A group of researchers at Case Western were able to look at the brains of learners in two conditions. In the first, the coach was judgmental, and focused on negatives and the past. In the second, the coach was empathetic, and focused on the future.

With the judgmental coach, the visual cortex showed limited activity. With the positive, future-oriented coach, however, it lit up like a Christmas tree. The researchers concluded that this correlated with someone imagining their future.

The takeaway: when it comes to learning, brains work exactly like flashlights. It’s not enough just to turn them on; they have to be pointed toward a target.

A few simple ways to do this:

Encourage expression about future goals. Where do they want to be a month from now? A year? Five years?

Ruthlessly eliminate negative statements — especially judgements — that cause brains to shut down.

Count down until some Big Future Event. How many practices do we have left until the tournament? How many more lessons until the recital? A calendar with Xs is a powerful tool.

How else? What other tips do you have for clicking on those flashlights?

July 1, 2012

How to Fix a Slump

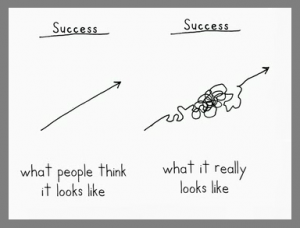

Ever see this diagram? (It’s from comedian Demetri Martin.)

I like this, because I think it’s true. From the outside, success looks like effortless progress; from the inside, we discover the journey is a lot more complicated. In fact, the most interesting part of the line is where it turns sharply downward, into one of those nasty-looking tangles where progress stops, development stalls, and frustration rises. It raises an interesting question:

What’s the best way to fix a slump?

Normally, when we hit a slump, we experience an overwhelming instinct to ignore it — to shut our eyes and just try harder, and hope things change. That makes sense — and it feels satisfying. But is it the best way?

We find an interesting case study from Andrew McCutchen, the Pittsburgh Pirates centerfielder. Drafted in 2005, McCutchen was a can’t-miss prospect, a first-round pick who performed outstandingly well for two years in the Pirates minor leagues — until, suddenly, he hit a dry spell. He stopped hitting. His average dropped to a puny .189. This was it: McCutchen’s slump, his crisis; his line was headed straight for the basement.

In this case, the Pirates organization used a surprising strategy. When McCutchen hit his downturn, they flew hitting coach Gregg Ritchie to visit him. Ritchie carried a piece of paper: a print-out of McCutchen’s hitting flaws — specific, targeted problems with his swing mechanics that Ritchie had noted a year and a half earlier.

Until that moment, McCutchen didn’t know the list existed. But now, working with Ritchie, he used this list of flaws like a blueprint. He lowered his hand position; he shifted his weight — together, player and coach fixed his swing. And it worked: McCutchen got out of his slump, and kept moving up. He’s now an All-Star.

I like this story because I think it gives us insight into how to best handle these downturn moments. We instinctively want to do it alone; to lift ourselves back on that upward track out of sheer will.

But what works better is to approach the slump more like a science problem. Cool off the emotion. Collaborate and gather information. Figure out the shortcoming, and start re-wiring the improvement. In a word, be agile.

I also like it because it shows the importance of organizational agility. The Pirates handled this well, because they understood when to make the intervention. Coach Ritchie knew all along McCutchen’s swing had potential problems, but he didn’t try to fix those problems early on because his swing was working (as McCutchen said, if coaches had tried to correct him, he would have ignored them — and rightly so). No, the Pirates wisely waited until the the problem arose — until they had McCutchen’s full and desperate attention. Then, together, they went to work and built a better swing.

Fixing slumps is not about solo strength. It’s about group agility.

June 12, 2012

Introducing Your Talent-Tip Hall of Fame

We just arrived in Alaska, where we’re spending a big chunk of the summer. So far, everything’s going well: family and friends are healthy, weather’s been solid, and during this morning’s coffee, we had an official welcoming committee: a newborn moose calf and its mother ambling through the backyard.

We just arrived in Alaska, where we’re spending a big chunk of the summer. So far, everything’s going well: family and friends are healthy, weather’s been solid, and during this morning’s coffee, we had an official welcoming committee: a newborn moose calf and its mother ambling through the backyard.

Speaking of arrivals, it’s exactly 10 weeks until The Little Book of Talent publication date (August 21). As a way of marking the countdown, I’d like to update one of my favorite posts from about a year and a half ago, when I asked you readers to name the single best tip — the best advice, the best strategy, the best practice tool — they’ve ever received.

Your responses (all 71 of them) were terrific — so terrific, in fact, that it seems a shame to let them be buried in the comments section of the old post. So with that in mind, I’ve combed through the tips and selected my top four favorites.

1) Slow is smooth, and smooth is fast (from Greg Sumpter)

I think we typically want to learn a skill as quickly as possible, and be done with learning it. If we could only slow down, break things down into small reproducible parts, and excel in a smoother way, we would get to the end product with excellence much more quickly.

Why I like it: Because it keeps me focused on what really counts: being accurate and efficient, and letting the speed come later.

2) Start with the End in Mind (Bill Dorenkott, Head Coach of Ohio State Women’s Swim Team)

My 20-minute drive to work allows me quiet time to employ this rule for my day, week and season. I find it much easier to reverse-engineer a challenge than to fly by the seat of my pants.

Why I like it: Because there’s a huge gap between mere activity and targeted work; this saves me time.

3) Cultivate Awareness (Kent Bassett)

Instead of engaging in a running commentary about all the mistakes to avoid, and keeping a list of all the mistakes made, you should cultivate awareness. It fires the more unconscious, creative part of the mind. You can even say to yourself, “I’m going to play this passage, and I’m not going to try to avoid mistakes. I might even try to make mistakes.” This counter-intuitive technique allows you to play more freely, and often, with fewer mistakes.

Why I like it: Because rather than getting governed by your mistakes (always a danger), this helps you focus on mastering them.

4) Feel pain, not hurt (Markus)

Feeling pain is a signal of growing and improving. [Feeling] hurt is a signal of stop which pause the flow of skill development.

Why I like it: Because it makes clear the useful distinction between good pain (stretch, struggle, reach) and bad pain (ouch).

What I really like, however, is the idea that this master list of talent-development tips exists, and that we can make it even more useful by sharing it and adding to it as time goes on. So with that in mind, here’s the entire list, along with a question: what are your favorites? What new tips need to be added?

June 8, 2012

What’s Your Coaching-Thought?

One strategy I’ve always found useful is the “swing-thought.” The term originates with golf; it refers to focusing on a single idea as you swing the club.

One strategy I’ve always found useful is the “swing-thought.” The term originates with golf; it refers to focusing on a single idea as you swing the club.

For example, one swing-thought might be SMOOOOTH. Or ROLL WRISTS. A good swing-thought works because it un-clutters the mind, clarifies focus, and captures the essence of your best performance.

Which makes me wonder: do the best coaches and teachers have the equivalent of swing-thoughts as they work? Are there key ideas coaches can use in the moment of teaching to help them coach better?

Based on my observations, I’d say that most master coaches have three distinct coaching-thoughts.

The first is CONNECT. They create a personal link; they use their interpersonal skills to capture the spotlight of the learner’s attention. Until that’s achieved, nothing useful can happen.

The second coaching-thought is ASK. The coach puts forth a task — it could be doing a drill or playing a song, or trying something new — it doesn’t really matter what it is, so long as the task 1) is unmistakably clear; 2) puts the learner on the edge of their ability (which is to say, it’s neither too hard nor too easy).

The third is RESPOND. The coach perceives what the learner is doing, and uses it to generate the next task. The next task might be more difficult, or it might be easier — all that matters is that it helps the learner navigate closer to the goal of proficiency.

Connect. Ask. Respond. This process isn’t a lecture from a podium. It’s more like a personal conversation that happens on the edge of the learner’s abilities.

When I coach, I find it useful to visualize what’s happening inside the learner’s brain: to picture the wires glowing, trying to connect, the new circuitry forming through each repetition. I know, it sounds sort of science-fiction-ish, but it works for me because it helps focus on the underlying process. Mistakes aren’t verdicts; they’re pieces of information you use to build the right connections.

Next question for you coaches and teachers: what images and ideas are going through your mind as you work? Are there any useful “coaching-thoughts” you’d like to share?

June 5, 2012

My First Reader

One of the big moments for a new book happens about 90 days before publication, when the bound galleys arrive from the printer. Bound galleys are basically a paperback with a generic cover, designed to be sent around for early readers. They are the dress rehearsals of the book world: not perfect, but close enough to give the feeling of the real thing.

Last week, the moment arrived. One of the first copies went to Andy Ward, my editor at Bantam/Random House, who brought it home to the busy, book-filled home he shares with his wife and their two soccer-playing, ballet-dancing daughters.

On Saturday morning, Andy was driving his younger daughter to her year-end ballet recital — a big deal, with an audience of 200 or so — when he turned around and saw this:

Andy reports she then went out and rocked the recital.

There’s something else you should know about Andy: his wife, Jenny Rosenstrach, is the author of a remarkable new book called Dinner: A Love Story, which is is designed to help families tap into the simple power of the family meal.

Now, I could tell you how well the book is written, or how fantastically useful and smart it is, or how beautiful it is. I could tell you how much I’ve learned from it already (how to properly fold a burrito — who knew?) or how my family and I are loving Jenny’s recipes.

But mostly, I just want to tell you that you should buy it. Also, check out their terrific blog.

May 31, 2012

What Does Great Practice Feel Like?

What’s your best practice made of? Novak Djokovic, top-ranked player in the world, gives us a peek at his recipe. (Click ahead to 1:05 for the best moments.) It includes:

1) Smallness: it focuses only on a few targeted qualities — improving touch, agility, and the ability to disguise shots.

2) Intensity: full-effort reaching, clear results.

3) Game-ishness: this is no boring drill. It’s the opposite — a thrilling, absorbing, emotion-generating game (as the ending shows).

In other words, it’s about creating SIG — Small, Intense Games. The next question: what’s the math-class version of this? The music-lesson version? The software-coding version?

May 29, 2012

How to Build Resilience

No matter what talent you’re building, resilience is a big factor; perhaps the factor. Defined as the ability to recover from adversity; resilience is the ultimate killer app because it allows us to adapt, to learn, to turn setbacks into progress.

No matter what talent you’re building, resilience is a big factor; perhaps the factor. Defined as the ability to recover from adversity; resilience is the ultimate killer app because it allows us to adapt, to learn, to turn setbacks into progress.

The mystery is, where does it come from? How is it developed? And perhaps most important, is it possible to teach?

One useful way to think about resilience is to think of it as the skill of controlling your emotions in negative situations. In this view, negative emotions are “hot” — they cause the brain to spark and short-circuit, they cause performance and confidence to dissolve in a cascade of doubt and judgement. Resilience is the skill of cooling those “hot” emotions and reinterpreting setbacks in a positive, future-oriented light.

We normally think of resilience as a response. The surprising thing about resilience, however, is that the most important moment comes before the negative event — it’s pre-silience. Studies show that resilient people start controlling their emotions before the stressful events begin. In other words, resilient brains function sort of like smart thermostats; even before the emotional heat arrives, they provide an anticipatory burst of cool, calm control.

Check out this study about Navy SEALs who were found to anticipate negative events by activating their emotional-control centers — in other words, before they encounter the negative event, their brains are already in calm-down mode.

The other interesting thing is that it seems this ability can be grown through practice. For instance, professional musicians who are preparing for a major performance will often pre-create, as closely as possible, the performance conditions, right down to the time of day, the clothes they’ll wear, the chair they’ll use.

NFL kickers like Billy Cundiff of the Ravens, who use bio-feedback devices to help teach them to regulate their stress levels in pressure situations.

Then there’s the wonderful example of Susan Cain, an introvert (and author of Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World that Can’t Stop Talking) who had to face her worst fear: giving a speech in front of a huge audience. (Long story short: she got coached, did nothing but rehearse for a solid week, and nailed it.)

They are all being pre-silient: creating the pressurized situation, over and over, to teach their brain to calm itself at the right moments. In this way of thinking, practicing resilience is not that different from practicing a golf swing. The keys are:

1) Pre-create the stressful situation. It’s not enough to imagine it vaguely — try to get every detail. Ideally, duplicate the atmosphere; if not, imagine it as vividly as possible: a golfer or musician might imagine the uneasy rustling of the crowd; a CEO might imagine the hush of an expectant boardroom.

2) No stopping allowed. Once the “performance” starts, you can’t give yourself an exit door; you need to endure it completely, get to the other side of it.

3) Repeat. Then repeat again. And again. Learning to endure and control spikes of intense emotion is like enduring any sort of stimulus: time and repetition are your best friends.

May 25, 2012

Dept. of Multitasking

Because just completing a triathlon isn’t enough (apparently).

May 23, 2012

The New Report Card: Forget an “A,” Try for an “M”

Four years ago David Boone was a homeless 15-year-old sleeping on a park bench in Cleveland, Ohio. This fall he’ll be entering Harvard.

Four years ago David Boone was a homeless 15-year-old sleeping on a park bench in Cleveland, Ohio. This fall he’ll be entering Harvard.

His is the kind of heroic story that would seem over-the-top in a movie, if it didn’t happen to be real: David used his book-bag as a pillow, studied in train stations, figured out how to avoid local gangs. (Read his story here.)

More interestingly, David’s not the only hero in this story. The other is his report card. Not because of its grades, but because of its design. You see, report cards at David’s school don’t have “A”s, “B”s, and “C”s. Instead, they have “M”s and “I”s.

M stands for Mastery; I stands for Incomplete.

This method is a product of remarkable new high school David attended called MC2 STEM, in which David is part of the first graduating class. The school, part of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation STEM Initiative, teaches science and engineering through hands-on, project-based learning in cooperation with a General Electric R&D facility across the street (translation: they don’t sit at desks listening to teachers talk).

As they learn, students are graded on specific skill-sets — called benchmarks — that make up each 10-week subject.

“M” means the student has mastered the benchmark skill (usually demonstrated by a score of 90-plus on a project or test).

“I” means the student needs to work more until they master the skill. They don’t retake the course — instead, teachers provide additional activities and opportunities for mastery, until it’s achieved.

It’s refreshingly simple: the mushy, judgmental landscape of Bs and Cs is replaced with a clear goal: mastery is expected; if you don’t get it right away, you will get new opportunities to work until you do. As David says, “They don’t accept mediocrity.”

I think one reason this technique is effective is that it uses grades the way they should be used: not as an often-demotivating verdict on identity (“You’re a C student); but rather as an ignitor of effort, a motivational north star. “Incomplete” is a motivating concept, because it sends a strong signal that complete learning is not only possible but expected; that everyone is capable of top-level work. It nudges the culture away from judgement and toward continual improvement and reaching. It turns a school into a skill-construction zone.

The question is, how can other organizations put this M/I grading method to work? For instance, could a soccer coach build a team around the idea of mastering certain moves? Could a businesses do the same when teaching employees? A music teacher?

Also, I’m curious: do you know of other simple methods that schools, teams, and businesses use to promote the love of mastery? If so, I’d love to hear about them.