Daniel Coyle's Blog, page 16

May 18, 2012

How to Imagine More Effectively

We usually think of our imaginations as idea-fountains: wellsprings of creativity.

We usually think of our imaginations as idea-fountains: wellsprings of creativity.

What’s interesting, though, is how often imagination is used by highly successful performers in their practice techniques. These people channel the fountain’s energy in a very particular way: they use their imagination to build a sensory template for the action they want to learn, speeding the learning process. They focus on pre-creating the feeling of a skill, projecting themselves inside an action so they can learn it faster and better.

Exhibit A: Wayne Rooney, Britain’s resident soccer genius. As this terrific article explains, Rooney spent much of his youth imagining as he practiced. He played in the dark, alone, inventing little games; imagined bricks as defenders; imagined street signs as goalposts. To this day, on the night before a game, he asks the equipment manager what color jersey his team will be wearing, so he can more vividly imagine himself going through game situations, over and over.

Rooney, famous for being a mumbly, half-literate lout, practically turns into a scientist/poet when he describes his technique: ”You’re trying to put yourself in that moment and trying to prepare yourself, to have a ‘memory’ before the game,” he says. “You work out what decision is the best, and then if you get in that position in the game, that comes back to you. It’s basically stored in your mind.”

Exhibit B: Two people, paralyzed from the neck down, who have taught themselves to use a robotic arm to reach out and grab objects. A chip is implanted in the motor area of the brain which responds to the electrical firing patterns.

So how did they learn this? Simple: the patients were instructed to stare at the robot arm while they watched researchers manipulate it, and to imagine themselves controlling it — reaching, twisting, tilting, grabbing. Like Rooney, they stared at the skill, they imagined, and then they did it. One woman, who suffered a stroke 15 years ago, was able to control the arm to a phenomenal extent: she grasped a cup of coffee and brought it to her lips (and also brought the researchers to tears; here’s the video).

These cases and others like them indicate that we carry around powerful, built-in mental machinery (perhaps mirror neurons) that assists us in skill acquisition, when we use it properly. Let’s call this technique projection, and let’s name its basic qualities:

1. It’s highly specific and detailed. You are imagining a single move (a chunk) in the deepest possible detail. The color of the jersey, the smell of the grass, the feeling of grasping the cup. It’s visualizing in sensory HD.

2. It has two steps. First, you stare at the target skill until you’ve built it in your mind. Then you project yourself inside that skill, focusing on what it would feel like.

3. It’s solitary. This isn’t something that’s done in groups, but alone, in quiet places, where you can operate without distraction.

4. It’s used in combination with intensive practice. All the vivid projecting in the world doesn’t help until it’s combined with a lot of high-quality reps.

In our busy lives it’s tempting to spend our learning time in a frenzy of activity. Maybe it would be smarter to spend more time with our eyes closed.

***

PS – On a completely different topic: with the new book (Little Book of Talent) arriving in August, we’re now looking for folks who might be interested to read early versions and maybe even provide a cover blurb. Any suggestions? I’m particularly interested in locating influential people in the blogosphere – mom/parenting-bloggers? teacher-bloggers? — who might find the book useful for their audience. Write suggestions below, or email me directly at djcoyle1@gmail.com. Thanks.

May 15, 2012

LBOT Preview: Meet Your Talented Illustrator

Here’s the thing no one tells you about writing books: you spend a great deal of time feeling clueless and lost.

I realize, you’re not supposed to say that. Writing a book is supposed to be a confident sequence of a-ha moments, that feeling of unstoppable creative momentum some writers like to call “taking dictation from God.” But for me, it feels more like walking through a dark forest, bumping my head into trees, hoping to get to the other side. It definitely isn’t taking dictation from God. More like, from Homer Simpson.

One of the key moments in the head-bumping journey of this new book (The Little Book of Talent, due out in August) happened not so long ago, when I realized that this book needed an illustrator. (In retrospect, hugely obvious, since this is a handbook filled with specific, concrete tips designed to help readers improve their skills/grow their brains. But at the time, not so obvious.)

I found myself magnetically drawn to the work of Mike Rohde. Mike’s work is simple, classic, beautifully clear, and best of all, has this uncanny knack for capturing ideas and turning them into vivid, memorable images.

When I called Mike about The Little Book of Talent, we started with the idea of doing six illustrations. Then it was twelve. Then twenty. Next thing we knew, Mike was cranking out no fewer than fifty-freaking-two separate drawings for LBOT, one illustration for each of the book’s 52 rules, an Olympic-level performance. For example:

Tip #25: Shrink the Practice Space Tip #51: Keep Your Big Goals Secret

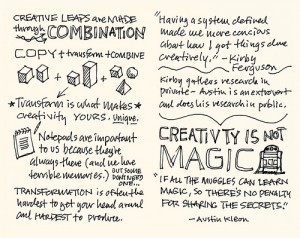

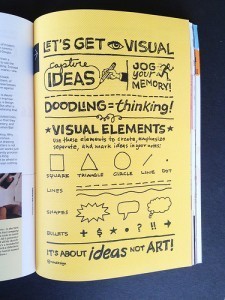

It turns out that Mike’s knack is not an accident. He’s a pioneer of a new kind of visual notetaking called sketchnotes. You might have seen it on the web, or at conferences. The idea is to replace the old ways of note-taking (words stacked on a page) with a combination of key words and images that capture the larger idea in a more concise, engaging way. Like this:

A good sketchnote quickly captures the essence of complicated ideas and relationships, distills them to a simple, memorable form. It works because it leverages the our brain’s natural ways of learning (focused on images and spatial relationships). Best of all, it changes the role of the note-taker from passive transcriber to active decision-maker; creator.

For more, check out Mike’s work here and his flickr collection here. But the big news is that he’s at work on a new book of his own: The Sketchnote Handbook from Peachpit Press, due in October. The idea is to help teach people how to use sketchnoting techniques in their lives, and give them some tools to start.

So now I’m trying this sketchnoting thing myself, in hopes that it helps me get lost less, or at least bump into the right problems more quickly. I’ll let you know how it goes.

May 10, 2012

Good Books

I was flipping through The Art of Fielding the other day (which is super-great, and just out in paperback). It’s about a few seasons in the life of a small-college baseball team and its unlikely star, Henry Skrimshander.

I was flipping through The Art of Fielding the other day (which is super-great, and just out in paperback). It’s about a few seasons in the life of a small-college baseball team and its unlikely star, Henry Skrimshander.

I was struck by how accurately and beautifully author Chad Harbach depicts the way a person grows their skills: the mix of obsession and focus and crazy love, the immeasurable power of deep repetition, how people really think and act as they work together to develop their talents.

For instance:

Baseball was an art, but to excel at it you had to become a machine. It didn’t matter how beautifully you performed SOMETIMES, what you did on your best day, how many spectacular plays you made. You weren’t a painter or a writer–you didn’t work in private and discard your mistakes, and it wasn’t just your masterpieces that counted.

Or this:

He already knew he could coach. All you had to do was look at each of your players and ask yourself: What story does this guy wish someone would tell him about himself? And then you told the guy that story.

You get the idea. The point is that The Art of Fielding takes us deep inside the process of growing talent in the same way that Moby Dick takes us deep inside the process of 19th-century whaling.

The other point is that, a lot of other books do the same. I think it’d be interesting, and maybe useful, to see if we could compile a running list — call it the “Talent Code Book Club.” The books could be fiction or nonfiction, about music or business or chess or painting; they could be written from a coach or teacher’s point of view or that of a kid — it doesn’t matter, so long as it takes us inside and leaves us with some fresh insights about what it means to try to get better.

A few that come to mind:

Born Standing Up , by Steve Martin

The Game , by Ken Dryden

On Writing , by Stephen King

Practicing , by Glenn Kurtz

Life , by Keith Richards

Among Schoolchildren , by Tracy Kidder

What other books — or even movies — should be on this list? I’d love to hear your suggestions.

May 8, 2012

Maurice Sendak (1928-2012) on the Big Stuff

I love this for a lot of reasons, especially for Sendak’s thoughts about the unmistakable feeling of doing good work at the 2-min mark. But really, the whole thing is worth watching.

“It’s sublime, to go into another room and make pictures. It’s magic time, where all your weaknesses of character, the blemishes of your personality, whatever else torments you, fades away, just doesn’t matter. You’re doing the one thing you want to do and you do it well and you know you do it well, and… you’re happy. The whole promise is to do the work, sitting down at the drawing table, turning on the radio, and I think, what a transcendent life this is, that I’m doing everything I want to do. In that moment, I feel like I’m a lucky man.”

(From ”Tell Them Anything You Want,” a beautiful film by Spike Jonze and Lance Bangs)

May 4, 2012

What Mastery Feels Like

Last night my lovely bride and I snuck out to the movies at Cleveland’s old Capitol Theater. Screen 1 showed a preview of the colossal whiz-bang new Avengers movie (we weren’t invited, naturally).

Screen 2, however, showed a movie about a real person with actual superpowers. His name is Jiro Ono, and he’s built himself into the best sushi chef on the planet (click the trailer above for a taste).

It’s a terrific, up-close portrait of the power of daily practice. Jiro, who’s 85, talks about how much more he has to learn. And the culture they’ve built inside this tiny shop — a culture of attentiveness, precision, and reaching — should be the envy of any organization or team. At one point, a chef tells of learning to make a difficult egg sushi. On the 200th try, he did it, and he wept with joy.

The takeaway wasn’t about the discipline; it was about the love that fueled the process. As author Jonah Lehrer recently put it, “love is just another name for “it never gets old.”

Inside Jiro’s shop, it never gets old. (Avengers, eat your hearts out!)

May 3, 2012

The Social Power of Sharing Mistakes

Much of the research about learning and the brain could be distilled into a few simple words:

Much of the research about learning and the brain could be distilled into a few simple words:

Mistakes are good. Struggle makes you smarter.

When it comes to applying this lesson to our lives, the problem is not with the science, but rather with our powerful natural aversion to mistakes and struggle.

Try as we might to convince ourselves otherwise, mistakes feel crummy; struggle feels like a verdict. Also, mistakes often carry a social price — they can cost us our job, our money, our pride. So we instinctively hide them.

The question is, how to fix that? How do you overcome your natural mistake allergy?

One good answer: do it as a group.

Last week I heard of a nice strategy from the headmaster of a private high school in Utah. It’s called the Mistake Club, and it got started, as most of these things do, by accident.

Backstory: A new assistant headmaster (let’s call him Ernest) had been asked to speak to one of the school’s biggest donors about an upcoming project. For various reasons, the conversation didn’t go well; by the time it ended the rich donor was royally ticked off. Ernest’s first instinct, naturally, was to hide the mistake; to tell no one.

But for some strange reason Ernest didn’t. He did the opposite. He told the headmaster and staff the whole fiasco, describing each detail of the train-wreck conversation. Someone made a joke that they should start awarding points for each screwup.

The Mistake Club was born. Meetings were weekly; points were awarded on a 1-10 scale — the bigger the screwup, the more you “earned.” At the end of the year, a “prize” was awarded to the person who’d accumulated the most points.

The benefits, of course, go far beyond the pleasure of the joke. The Mistake Club established a culture of trust and communication. When someone shares the details of their mistake, the whole group learns vicariously. Social ties are strengthened. The meetings turn into coaching sessions; the organizational brain gets smarter.

Here are few other ways to do that:

Control expectations: I’ve seen sports teams and businesses sign contracts at the beginning of a season affirming that people will make mistakes, struggle will happen.

Deliver praise during the struggle: instead of praising someone at the moment of their achievement, praise them during their effort — since this is the behavior that really matters, and that you want to create again.

Encourage fallibility in leaders: it’s far easier for everyone to be transparent when leaders set the tone. For example, I recently heard of a hospital CEO who wanted to encourage hand-washing. She offered a reward of $20 to any worker who noticed her entering a sterile area without washing her hands first. Showing her own fallibility makes it easy for others to show theirs.

Legislate risk: Some companies build risk-taking requirements into their culture. For instance, Living Social, the online coupon company, encourages its people to take a business risk that scares them once a week.

The point is to find some way to create a safe social place where mistakes can be made and then used to accelerate learning — an inoculation for our natural mistake allergy. As with any inoculation, a small dose can have a big effect.

April 27, 2012

The Kid Who Loves Music

Ethan Walmark is six, he’s got autism, and he loves playing piano (he’s been learning by ear since he was tiny). Here, he plays one of his favorites: “Piano Man,” by Billy Joel. It’s worth a listen.

People talk about passion so often that it can sometimes feel like an abstraction. It’s nice to see a reminder what it looks like, and what it feels like.

(Not to mention where it can lead.)

April 25, 2012

The Power of Small Wins

Most of us instinctively spend a lot of time and energy seeking the big breakthrough: that magical moment when, after a lot of effort, everything finally clicks: when you play the song perfectly, ace the test, win the big game. Those moments are incredibly satisfying. But they’re also a problem.

Most of us instinctively spend a lot of time and energy seeking the big breakthrough: that magical moment when, after a lot of effort, everything finally clicks: when you play the song perfectly, ace the test, win the big game. Those moments are incredibly satisfying. But they’re also a problem.

Here’s why: focusing on the big breakthrough can cause you to overreach. It can create a steady diet of disappointment (after all, breakthroughs are rare, by definition). Worse, you stop focusing on the smaller, incremental things that really matter.

The best performers and teachers I’ve seen don’t get caught up in seeking big breakthrough moments. Instead, they hunt the little breakthroughs — the small, seemingly insignificant progressions that create steady daily progress. In short, they love baby steps.

Teresa Amabile and Steven Kramer explore this idea in their fascinating book The Progress Principle. In it, they analyze 12,000 diary entries from 238 subjects to get a picture of the subjects’ inner work lives. They conclude that the common trait of highly successful subjects is that they are focused on achieving “small wins” — those tiny, daily progressions that don’t seem like much but which add up, over time, to big things.

The payoffs of a “small-win” mindset are clear: you tend to be less disappointed, and more motivated. You stay focused on the present. You don’t overreach by taking shortcuts and trying to do everything at once.

Perhaps most important, the “small-win” approach is aligned with the way your brain is built to learn: chunk by chunk, connection by connection, rep by rep. As John Wooden said, “Don’t look for the big, quick improvement. Seek the small improvement one day at a time. That’s the only way it happens – and when it happens, it lasts.”

A few ideas for a small-win mindset:

Keep a daily notebook: Name the small changes you make each day.

When you get a small win, freeze: Don’t breeze past small improvements; instead, take a few seconds to acknowledge and celebrate them.

Aim for a daily SAP — Smallest Achievable Perfection. Pick one little thing to perfect in a single day — one move, one action, one chunk. Work on it until it’s polished, until you can’t not do it right.

I’d love to hear if you have more ideas for making small wins.

April 19, 2012

A Solution for “The Parent Problem”

As I’ve traveled around talking to teachers and coaches, there’s one refrain I hear over and over: The kids are great. The problem is the parents.

As I’ve traveled around talking to teachers and coaches, there’s one refrain I hear over and over: The kids are great. The problem is the parents.

I think this is deeply true, most prominently in youth sports, but also in other areas, like music and the classroom. It’s not because parents are dumb or ill-intentioned — though, okay, some are — it’s rather because a lot of parents genuinely want to help, and don’t know how best to do it, so they helicopter around and that makes things messy (I’ve been there, done that).

With that in mind, check out this letter written a few years back by a new Little League baseball coach to his team’s parents before the season began. And what makes it slightly more meaningful is that the Little League baseball coach happens to be Mike Matheny, who’s gone on to be the manager of the St. Louis Cardinals (he coached Little League just after he retired from pro ball).

If you’re curious, I would recommend clicking this link to read the whole thing, but here are a few excerpts:

I always said that the only team that I would coach would be a team of orphans, and now here we are. The reason for me saying this is that I have found the biggest problem with youth sports has been the parents. I think that it is best to nip this in the bud right off the bat. I think the concept that I am asking all of you to grab is that this experience is ALL about the boys. If there is anything about it that includes you, we need to make a change of plans. My main goals are as follows:

(1) to teach these young men how to play the game of baseball the right way,

(2) to be a positive impact on them as young men, and

(3) do all of this with class.

We may not win every game, but we will be the classiest coaches, players, and parents in every game we play. The boys are going to play with a respect for their teammates, opposition, and the umpires no matter what.

Once again, this is ALL about the boys. I believe that a little league parent feels that they must participate with loud cheering and “Come on, let’s go, you can do it”, which just adds more pressure to the kids. I will be putting plenty of pressure on these boys to play the game the right way with class, and respect, and they will put too much pressure on themselves and each other already. You as parents need to be the silent, constant, source of support.

I am a firm believer that this game is more mental than physical, and the mental may be more difficult, but can be taught and can be learned by a 10 and 11 year old. If it sounds like I am going to be demanding of these boys, you are exactly right. I am definitely demanding their attention, and the other thing that I am going to require is effort. Their attitude, their concentration, and their effort are the things that they can control. If they give me these things every time they show up, they will have a great experience.

I need all of you to know that we are most likely going to lose many games this year. The main reason is that we need to find out how we measure up with the local talent pool. The only way to do this is to play against some of the best teams. I am convinced that if the boys put their work in at home, and give me their best effort, that we will be able to play with just about any team.

The thing I like most about this letter is how it so clearly establishes the relationship, and does so in a big-picture, friendly, personal way. As a parent, I wish I would have gotten more letters like this. As a former Little League coach, I’m wondering, why the heck didn’t I send one?

Why don’t more teachers and coaches use this technique? Could it be possible to use letters like this as a tool to change the dynamic, so that parents might stop being a problem and start being more of an asset?

(Big thanks to John Kessel and Jennifer Armson-Dyer for the heads up.)

April 16, 2012

To Learn Faster, Raise the Stakes

The other day Stephen, my daughter’s violin teacher, pointed out a pattern he’d noticed when he was teaching his students to play difficult passages.

The other day Stephen, my daughter’s violin teacher, pointed out a pattern he’d noticed when he was teaching his students to play difficult passages.

When he instructed students to try to play it perfectly five times, the kids learned slowly. Some kids took thirty tries to get the five perfect ones; others took a hundred; some never got it.

However, when he told the kids to try to play it perfectly five times in a row and if they missed they started again at zero, they learned it far faster. Instead of fifty tries, it took ten. “Much, much faster,” was how Stephen described it.

When you tell someone they need to do a task perfectly, but are vague about how it needs to be done, part of the learner’s brain switches off. The subconscious message is: take as long as you need, buddy. Every try isn’t really that important. Don’t worry, it’s just practice.

The vagueness serves as an escape hatch. (Which is completely natural — remember, our brains are always searching for an excuse not to give effort.)

However, you provide clarity plus urgency — say, when you tell someone that they need to do a task well five times in a row and if they miss they go back to zero — you’re sending a completely different signal. Now the subconscious message is: every single try matters immensely — and if you get one or two in a row, the importance increases even more. This is for keeps.

It reminds me of this great passage in Keith Richards’ autobiography, Life, where he talks about his songwriting technique:

You’d be surprised when you’re put right on the ball and you’ve got to do something and everybody’s looking at you going, OK, what’s going to happen? You put yourself there on the firing line — give me a blindfold and a last cigarette and let’s go. And you’d be surprised by how much comes out of you before you die.

Good practice is designed to create that feeling. You’re on the line. The clock is ticking; every rep is pressurized. Good practice nudges you out onto the knife edge, over and over. Because that’s the place where skills are built.

There are lots of straightforward ways to raise the stakes in practice: limit time, count reps, make it a contest, track progress from day to day and week to week, post results. The real trick is to raise the stakes by the right amount; you want to hit the sweet spot where it’s seriously challenging but still do-able, where each failure teaches a clear lesson, and where each success builds to the next.

How else can you raise the stakes? I’d love to hear your techniques.