Carl E. Olson's Blog, page 146

June 23, 2013

A “Laboratory of Ecumenism”: Cardinal Koch Visits Ukraine

A “Laboratory of Ecumenism”: Cardinal Koch Visits Ukraine | Michael J. Miller | CWR

Ecumenical trip marked by candor and optimism

The president of the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian

Unity, Cardinal Kurt Koch, visited Ukraine from June 5 to 12, 2013. Upon his arrival the curial official was

welcomed at Borispol Airport by the primate of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic

Church (UGCC), His Beatitude Sviatoslav (Shevchuk), and by Archbishop Thomas

Edward Gullickson, apostolic nuncio for Ukraine. Since it was the first journey of the honored

guest to Ukraine, his chief purpose was to meet with the Greek, Latin, and

Armenian Catholic communities and their respective leaders in a country that

Bl. John Paul II had called “a laboratory of ecumenism” during his pastoral

visit in June 2001. Cardinal Koch spent

two days in Kyiv, the capital, then traveled on Saturday to Lviv in Galicia

(Western Ukraine), a Catholic stronghold, and finally on Monday to Uzhorod and

Mukachevo, near the border with Slovakia and Hungary.

Cardinal Koch is also the co-chairman of the Mixed

Commission for Theological Dialogue between Catholic and Orthodox

Churches. In that capacity he held talks,

during his visit, with the Ukrainian Orthodox Church leader, Metropolitan

Volodymyr, of the Moscow Patriarchate (UOC MP), and other representatives of that

Church. He also learned about the

inter-confessional fellowship that takes place within the framework of the

All-Ukrainian Council of Churches and Religious Organizations, and about the

work of Institute of Ecumenical Studies at the Ukrainian Catholic University

(UCU) in Lviv.

Past documents of the official Catholic-Orthodox ecumenical

dialogue have typically ignored or papered over crucial differences in how the

two sides understand Church and authority.

The keynote of Cardinal Koch’s visit, however, was a refreshing candor on the part of the

Catholic speakers. On June 10, in a

lecture at Ukrainian Catholic University, he explained that:

The Most Popular Moral Heresy in the World

The Most Popular Moral Heresy in the World | Mark P. Shea | CWR

Consequentialism and why we can’t do evil so that good may come of it.

In the previous two pieces in this space, we have looked at two

fallacies: the ad

hominem and the genetic

fallacy. Both fallacies are, like

all fallacies, bad ways of trying to achieve good ends. For arriving at Truth is, of course, a very

good end, but fallacies are poor ways to get there. To be sure, sometimes even fallacious arguers

can occasionally arrive at truth despite their bad arguments. So, for instance, it may be that the guy I

claim is too ugly to understand science is also factually wrong about the earth

being 6,000 years old. It could be that

the member of the McCoy clan whose every utterance I and my fellow Hatfields

reflexively reject is, in fact, wrong about the infield fly rule. But the fact remains that I arrived at a true

conclusion despite, not because of,

my ad hominem or genetic fallacy. It was

a matter of dumb luck, like throwing my racket and scoring a point in

tennis. If I learn from this experience,

“Throw my racket more” and not, “Learn to play tennis better” I may get lucky

now and then, but the (pardon the pun) net result will be that I become a

terrible tennis player.

Likewise, if you stick with fallacious reasoning, you may now and

then reach a good end by accident, but the overall result will be that you will

not reach the end you seek, but something evil.

It may be an intellectual evil such as wilful stupidity or it may be a

moral evil such as talking yourself into knocking over a Qwiki Mart in the name

of economic justice. Very often, it will

be both. But it will not ultimately be

anything good because good ends do not justify evil means.

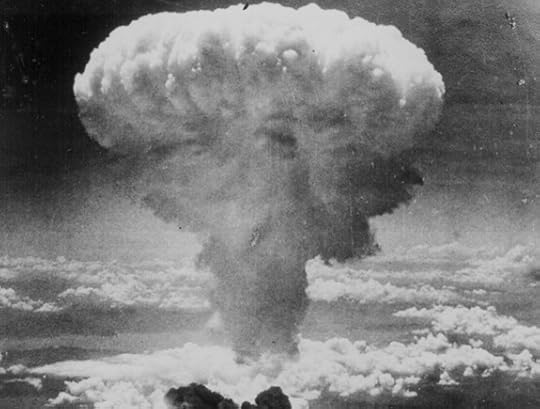

The notion that good ends do justify evil

means—also known as “consequentialism”—is probably the most popular moral

heresy in the world. We all believe it

to some degree or other. You could argue, in fact, that it’s practically the

definition of sin. It’s what Adam and

Eve attempted when they sought the good end of “wisdom” by the evil means of

disobeying God. It’s what everybody

tries every time we sin. And we do it

because we all want something good: we all want happiness.

Everybody? Even…Hitler?

Yeah. Everybody. Every sin is committed in pursuit of

something good. Power, money, health,

peace, security, comfort, sex, love, honor: all these things are good in themselves.

It’s only when we try to get them by disordered means that evil comes into the

picture. And in fact, the nobler the

goal you seek, the greater the temptation can be to do something monstrous to

get it. So in Hitler’s case, he thought

he could get happiness through a renewed and powerful Germany and he thought he

could get that via race war and mass murder. World War II and the Holocaust were caused,

as all evil is caused, by people looking for happiness in radically wrong ways.

At this point, the cry will often go up, “Stop humanizing

Hitler!” That cry against humanizing a

human is telling: Why on earth is it offensive to point out that Hitler was, in

fact, a member of the same species we are and subject to the same desires we

are?

Answer: because we want to believe that Bad People are motivated

by pure evil while we are motivated by basic goodness.

So the interior narrative goes something like this:

June 22, 2013

Thirsting, Seeing, and Believing

A Scriptural Reflection on the Readings for Sunday, June 23, 2013 | Carl E. Olson

Readings:

• Zec 12:10-11; 13:1

• Ps 63:2, 3-4, 5-6, 8-9

• Gal 3:26-29

• Lk 9:18-24

St. John of the Cross (1542-1591) produced several profound

works of mystical theology, filled with powerful descriptions of the soul being

purified by God’s burning love. Writing in his Spiritual Canticle of this work of sanctification, he stated, “The very

substance of soul and body seems to be dried up by thirst after this living

well of God, for the thirst resembles that of David when he cried out, ‘As the

hart longs for the fountains of waters, so my soul longs for You, O God.’”

Thirsting after God—what John often called “the thirst of

love”—is described many times in the Psalms and in the writings of mystics. It

can rightly be said that David the Psalmist was a mystic, just as St. John was

a poet of the highest order. Both the poet and the mystic seek to reveal the

deepest recesses of the soul and express their longing for the transcendent. “My

soul is thirsting for you, O Lord my God,” David cries out in today’s

responsorial Psalm, “O God, you are my God whom I seek; for you my flesh pines

and my soul thirsts like the earth, parched, lifeless and without water.”

The prophets also expressed this desire for God, usually focused on the people of

God as a whole. The prophets Zechariah and Haggai were the first prophets of

the post-exilic period, writing in the sixth century B.C., following the

Babylonian captivity (c. 597-538 B.C.). They were the “prophets of a new

beginning,” wrote Fr. Eugene H. Maly in Prophets of Salvation (Herder and Herder, 1967), “Both were concerned with

the rebuilding of the temple.” And both saw a coming time when God would “bring

history to its appointed climax.”

This would be accomplished, we hear in today’s reading from

Zechariah, when “a spirit of grace and petition” was poured out on those in

Jerusalem. This would involve mourning and grief on the part of those who had

“pierced” the Messiah, a prophecy describing the crucifixion of Jesus Christ.

Yet there is hope, for there will be “a fountain to purify from sin and

uncleanness”, a prophetic description of the sacrament of baptism.

That same sacrament, by which men are cleansed of original

sin and made sons of God, is the focus of today’s epistle, from St. Paul’s letter

to the Galatians. Those who have been baptized, Paul stated, are “children of

God in Christ Jesus,” having been clothed with Christ—that is, putting on

Christ and a new nature, divinized by the life of the Trinity (cf. Eph. 4:24; Catechism

of the Catholic Church, 1243, 1988). Adults

baptized in the early Church donned white baptismal garments after receiving

the sacrament; the first martyrs were described by John the Revelator as having

“washed their robes and made them white in the blood of the Lamb”. And those

who enter into the throne room of God wearing the white robes “shall hunger no

more, neither thirst any more” (Rev. 7:14-17).

Today’s Gospel reading does not refer to thirsting, but

there is certainly a connection to be made. The Evangelist Luke provides a

pithy account of Jesus asking the disciples, “Who do the crowds say that I am”?

(cf. Matt. 16:13-20). The answers vary, but are incorrect. “But who do you say

that I am?” Peter gives the correct answer. The disciples, thirsting after

truth, had given up everything to be with Jesus—and thus knew him far better

than did the crowds. Yet they would still have to learn further that such

thirst will only be satisfied by accepting Jesus for who he really is and what

he really did, by embracing his call to take up the cross, and by being

obedient unto death.

But, then, baptism is death—and new, divine life. “The

trials of this world,” wrote St. John of the Cross, “the rage of the devil, and

the pains of hell are nothing to pass through, in order to plunge into this

fathomless fountain of love.”

(This "Opening the Word" column originally appeared in the June 20, 2010, edition of Our Sunday Visitor newspaper.)

June 20, 2013

Lessons of the Past: A Review of "Lions of the Faith"

Lessons of the Past | William Kilpatrick | CWR

A review of Andrew Bieszad’s Lions of the Faith: Saints, Blessed, and Heroes of the Catholic Faith in the Struggle with Islam

Lions of the Faith chronicles the lives of saints, martyrs, and heroes who were caught up in the struggle between Islam and Christianity that commenced in the seventh century and continues to this day. The 800 martyrs of Otranto who were recently canonized by Pope Francis appear in these pages, as do the seven monks of Tibhirine, Algeria whose death at the hands of Islamic terrorists in 1996 is the subject of the 2010 film Of Gods and Men. The author also tells the story of many lesser-known saints, such as St. Casilda of Toledo, who was a Muslim but converted to the faith as a result of her contact with the Catholic prisoners for whom she secretly cared. In addition to saints and martyrs, Lions of the Faith also provides brief accounts of the exploits of Catholic heroes such as Charles Martel, who turned back a Muslim army in the pivotal battle of Poitiers in 732, and King John III Sobieski, whose 1683 victory over the Turks at the Gates of Vienna initiated the decline of the Ottoman Empire.

Although most of the book is concerned with the first thousand years of struggle between Islam and Christianity, it is as contemporary as today’s news. As the author observes, nothing has really changed: the basic problems and differences between Christianity and Islam remain. Chief among these is the Islamic conviction that all other religions must be subjugated under Islam. Thus, as Bieszad notes, “The reality which the seventh-century Church faced is the same in the 21st century.”

One of these realities—a reality that is still very much with us—is that Western Christians were rarely able to achieve unity in resisting Islamization. In fact, on numerous occasions Christian kingdoms allied themselves with the Muslim Ottoman Empire against other Christians. “Better a Turk than a Papist” was a popular slogan among Dutch Calvinists, and in their fight against Catholic Spain, Dutch sailors wore a crescent-shaped medal with that inscription.

Throughout much of the 16th and 17th centuries, Catholics were fighting a two-front war—against Muslims in the south and east and against Protestants in the north.

Man of Steel and Cross of Wood

Man of Steel and Cross of Wood | Nick Olszyk | CWR

Man of Steel is the superhero movie Catholics were waiting for, and it was worth the wait.

MPAA Rating, PG-13

USCCB Rating, A-III (Adults)

Reel Rating, (5 Reels out of 5)

Among the great Christ figures of world literature, Superman is our country’s best such figure by, literally, leaps and bounds. And Man of Steel is his best depiction yet, a towering achievement of both entertainment excellence and theological inspiration. It demonstrates how to make a Christological story the right way, complete with a villain that is both disturbing and appropriate for our post-modern age.

It is the end of the world, for Krypton at least. This world is dying in exactly the same fashion as ours: overdependence on science, disrespect for the human person, and unrepentant pride. Krypton is a haunting view of the secular revolution brought to its climax. The scientist Jor-El has a secret hope that will save at least one of his people: he and his wife have a son, the first natural birth in hundreds of years. The villainous General Zod calls this an act of “heresy,” because on Krypton children are bred for specific, socially conditioned lives and harvested only for the good of the state.

Fortunately for Earth, Jor-El’s son makes it to our planet and is adopted by a loving family in Kansas, taking the name Clark Kent. His supernatural abilities of flight, strength, and x-ray vision come from alien DNA but his dignity, goodness, and sacrificial love from human parents. Aware of his uniqueness, he patiently waits for years, learning to be human and helping people quietly. His decision to reveal himself comes in a conversation with a Catholic priest, a scene that is beautifully reminiscent of the Baptism in the Jordan and the Wedding Feast of Cana.

June 19, 2013

When the State Replaces God

When the State Replaces God | CWR Staff | Catholic World Report

An interview with Benjamin Wiker, the author of Worshipping the State: How Liberalism Became Our State Religion

Benjamin Wiker is a senior fellow at the St. Paul Center for Biblical Theology, a contributor to Catholic World Report, and the author of several books, including the recently published Worshipping the State: How Liberalism Became Our State Religion(Regnery, 2013). He spoke with CWR about his book.

CWR: Isn’t the title of your book hyperbolic and simply meant to stir up interest? Can it really be argued that anyone, at least in the United States, really worships the state? Whatever do you mean by that?

Wiker: Well, it’s certainly meant to stir up interest! Do people in the US, especially from the Left, physically get down and bow before, say, the steps of the Supreme Court? No! But do they treat the state as a kind of substitute for God? Yes, very much so. Is there precedent in the history of liberalism for an actual worshipping of the state? Again, yes.

We first have to stand back and look at our current situation within a larger historical framework. Over the last two hundred years, self-consciously secular states have, quite literally, transferred worship from God to humanity itself, or more precisely, to the greatest concentration of human power, the state.

The French Revolution’s Religion of Reason was actually a worship of man himself, and the secular revolutionary state made up its own religion, so that the revolution itself and the revolutionary state became the object of actual religious devotion.

This same kind of movement—rejecting Christianity, only to idolize the secular state—occurred with various other political movements in the 19th and early 20th centuries: nationalism, communism, Fascism, and Nazism are the most obvious examples. For good reason, scholars have called these “political religions.”

Socialism was one more political religion, which quite literally understood itself as transferring the worship from God to humanity itself, or more exactly, to the socialist state that promised to give citizens in this life what Christianity had promised only in the next—a this-worldly utopia. Socialism was, therefore, essentially religious in its original conception, and it became the historical foundation of liberal progressivism in the United States.

So, yes, we are talking about actual worship of the state! But we can also see, even aside from this historical background, that the liberal state has taken upon itself the role of God, even while it busily evicts Christianity from the public square.

Let me offer one important example, President Obama’s HHS mandate, compelling all institutions, including Catholic institutions, to pay for contraception, abortifacients, and sterilization. That’s the liberal state saying, “Thou shalt participate in the liberal sexual revolution.” That’s the state defining good and evil.

The same thing is occurring with the Left’s use of the courts to impose the acceptance of gay marriage, or the state, with abortion and euthanasia, taking upon itself the authority to define what marriage is, what life is, and when death should be dealt.

CWR: There are, as you note, many types of “liberalism.” What form of liberalism is your book about? And why do you write that “we cannot even understand liberalism until we understand some important things about Christianity”? What things?

Continue reading at www.CatholicWorldReport.com.

June 17, 2013

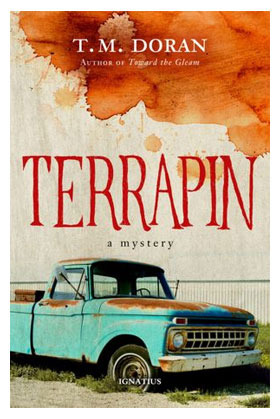

"Terrapin" recommended as a "compelling mystery novel" and an "exceedingly complex tale"

Mary McWay Seaman reviews T. M. Doran's novel, Terrapin: A Mystery (Ignatius Press, 2012) for New Oxford Review:

A careful reading of this compelling mystery

novel uncovers bounteous symbolism and multiple cryptic  allusionssurrounding a long-hidden crime and several adolescent indiscretions.

allusionssurrounding a long-hidden crime and several adolescent indiscretions.

That said, readers should steel themselves early on against urges to

overanalyze events in this exceedingly complex tale. The temptation to

“find” themes quickly or to identify culprits is tricky as T.M. Doran’s

intricate thriller, Terrapin, braids common strands from four

men’s pasts to underscore the point that no one emerges wholly unscathed

from the vicissitudes of youthful villainy. The long-dormant villainy

in this case explodes unexpectedly into the four perpetrators’ lives

during their sports-weekend reunion in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Aficionados

of suspense fiction will appreciate the book’s surreal plot, its brisk

pace, and its snappy repartee.

And:

Doran’s prose proclaims that mortals drag their

childhoods with them through life’s long fight, and that each

generation inhabits its own culture within the same country. Be that as

it may, the novel’s unimaginable ending demonstrates that fraudulent

intellectual and moral gymnastics in any culture are no match for the

ongoing, unmitigated ramifications of malice on perpetrators and victims

alike, ramifications that play forward in ways seen and unseen, whether

or not they are ever acknowledged.

Read the entire review on the NOR website.

For more about the novel, or to purchases it, visit the Ignatus Press site, or go to the Terrapin book site to view a trailer, read excerpts, download a free short story, and learn more about Doran and his writing.

Last September, CWR interviewed Doran about his writing:

CWR: Who are some of the authors and

thinkers who have influenced you the most?

Doran: As to literature, Evelyn

Waugh, Flannery O'Connor, J.R.R. Tolkien, and T.S. Eliot, writers and poets who

wrote from a Catholic perspective rather than writing explicitly Catholic

novels. I read a variety of writers: Jane Austen, Dostoevsky, Patrick O'Brian,

Thornton Wilder, Oscar Wilde, Dickens, Richard Adams, and I have learned

something about the craft of writing from every one of them. I enjoy mystery

stories, especially the golden age puzzle-plot stories from the 1920s through

the 1940s. Some of my favorite mystery authors are G.K. Chesterton, Agatha

Christie, J.D. Carr (the locked room master), Rex Stout, and the early Ellery

Queen mysteries that featured pure "ratiocination". I enjoy P.D.

James, who is still writing.

I have been an avid reader of history and biography for decades, which helped

immensely when I was composing Toward the Gleam

Thinkers who have influenced me include Blessed John Paul II (especially

"Faith and Reason" and "The Splendor of the Truth"), Edith

Stein (her journey from phenomenology to the convent), Kurt Goedel (his ideas

about time and space), G.K. Chesterton, C.S. Lewis and Frank Sheed (their

accessible apologetics), Blaise Pascal (reason in the light of faith), William

F. Buckley (conservatism based on first principles and natural law), and

Augustine and Aquinas (a little at a time). I have a four-volume Encyclopedia

of Philosophy on my bookshelf, to which I

refer quite often. I've always had a fascination with competing ideas.

Ecumenism and Canon Law

Ecumenism and Canon Law | R. Michael Dunnigan | CWR

Thoughts on Cardinal DiNardo's recent decision to allow the Methodist ordination of a woman in the Co-Cathedral of the Sacred Heart in Houston

Cardinal

Daniel DiNardo, the Archbishop of Galveston-Houston, recently permitted the

United Methodist Church to celebrate an ordination service at the Catholic

Co-Cathedral of the Sacred Heart in Houston. This event has set in motion a

wave of criticism on orthodox Catholic blogs and websites. The criticism

generally has focused on the fact that the Catholic Church does not recognize

the validity of Methodist ordinations, and the fact that the presiding

Methodist bishop was a woman. The prevailing critiques also charge Cardinal Di

Nardo with the sin of scandal. However, the commentary to date has included

little discussion of the law of the Church.

A

follower of the vigorous criticism directed against Cardinal DiNardo might be

surprised to learn that the cardinal’s decision enjoys relatively strong

support in canon law. I do not mean that the law commands the accommodation that Cardinal DiNardo made for the

Methodists, but rather that it provides him with ample discretion to make such a decision. Although the primary

purpose of churches and cathedrals is for Catholic worship, canon 1210 makes

allowance for some other uses of sacred

places as well.

What

other uses are permissible? Such uses must

be only occasional, and they must not be opposed to the holiness of the place

(cf. can. 1210). An example of an activity that would be contrary to the holiness

of a church would be a political rally. By contrast, a legitimate other

activity that might occasionally be held in

a church would be a historical lecture.

Does

a Methodist liturgy qualify as a legitimate other use of the Catholic cathedral? Canon 1210 itself does

not directly answer this question, but the breadth of its language seems to allow

any occasional use that is not contrary to the sacredness of the place.

Moreover, in the 1993 Ecumenical Directory, the Holy See says outright that it sometimes is permissible for a

non-Catholic liturgy to take place in a Catholic church.

Many

Catholics will be surprised to learn this.

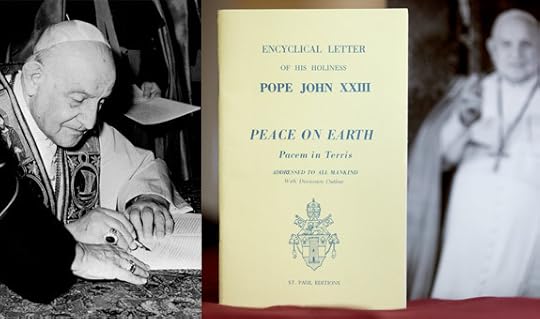

"Pacem in Terris" at 50

Pacem in Terris at 50 | J. J. Ziegler | CWR

Written in the midst of the nuclear arms race and the Cold War, John XXIII’s landmark encyclical contains important messages for our world today.

On April 11, 1963, The Beverly Hillbillies was the top television show in the

United States, works by J. D. Salinger and John Steinbeck topped the fiction

and nonfiction bestseller lists, and the lead headline in the New York Times was “Atom Submarine with 129 Lost in Depths

220 Miles Off Boston; Oil Slick Seen Near Site of Dive.” The Chiffons’ “He’s So

Fine” was the nation’s most popular song; It Happened at the World’s

Fair, starring Elvis Presley, was the most popular movie. And

Blessed John XXIII issued Pacem in Terris (“Peace

on Earth”), the first papal encyclical addressed not only to the Catholic

faithful, but also to all men of good will.

“By

addressing an encyclical on peace to all men of good will, John XXIII was not

merely being good Pope John,” says Mary Ann Glendon, president of

the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences and the Learned Hand Professor of Law

at Harvard Law School. “He was insisting that the

responsibility for setting conditions for peace does not just belong to the great

and powerful of the world—it belongs to each and every one of us. That’s

crystal clear in the closing paragraphs where he says, ‘There is an immense

task incumbent on all men of good will’—the task ‘of bringing about true peace in the

order established by God.’ It’s ‘an imperative of duty; a requirement of

love.’”

Blessed John wrote his encyclical

letter de pace omnium gentium in veritate, iustitia,

caritate, libertate constituenda, according to the encyclical’s

Latin title—“about

establishing the peace of all nations in truth, justice, charity, liberty,” or

as the phrase is more loosely rendered in the

most popular English version, “on establishing universal peace in truth,

justice, charity, and liberty.” The official Latin version appears in Acta

Apostolicae Sedis (beginning on page 257); the Vatican website’s

Latin

version contains additional notes and at least one Latin error that did not

appear in the original. The official version contains five untitled sections

with unnumbered paragraphs.

The Italian version contained section

titles, subsections, and subsection titles where none exist in the official

Latin text. The translator of the most popular English version, which

originally appeared in the publication The Pope Speaks,

incorporated these Italian additions, while the translator of another English

version, found here,

did not. This latter English translation has the advantage of adhering more

closely to the Latin in the body of the encyclical; unfortunately, it does not

retain the original division into five sections, thus making the encyclical

appear less structured than it is really is.

Reaction and

influence

Pacem in Terris is an extended

reflection on the moral order. “The Creator of the world has imprinted in man’s

heart an order which his conscience reveals to him and enjoins him to obey,”

the pontiff wrote (no. 5), explaining:

Star Trek: There and Back Again

Chris Pine and Zachary Quinto star in a scene from the movie "Star Trek Into Darkness."

Star Trek: There and Back Again | Nick Olszyk | Catholic World Report

A Review of Star

Trek Into Darkness

MPAA Rating, PG-13

USCCB Rating,

A-III

Reel Rating:

(3 Reels out of 5)

(3 Reels out of 5)

If

you’re not in on the joke, Star Trek Into Darkness is a lot of fun. If you’re in on the joke, it’s even

more. The film’s greatest strength lies in the fact that it’s essentially a flashy

remake of a classic episode from the original series but with clever twists and

turns that throws the story in a new and exciting direction. Yet even apart

from its predecessors, this is a thrilling popcorn film designed to enthrall

audiences with 3D special effects, witty dialogue, and poorly researched

scientific explosions in space all with a cast of overly attractive actors.

However, if you reach beneath the popcorn kernels at the bottom of the bucket,

you will find that Into Darkness

has remembered the central moral principles that made Gene Roddenberry’s

original vision compelling: life is an objective good, love requires sacrifice,

and the law was made for man, not man for the law.

The

story begins in a volcano, which is always a good place to start. Spock is

attempting to deactivate it from the inside to save a primate civilization

without being seen by the natives. When the plan goes awry, Kirk and the

Enterprise swoop in to save him, breaking their cover in spectacular fashion.

This whole adventure is a direct violation Starfleet’s Prime Directive, the

guiding principle of non-intervention. Kirk would never hesitate to break the

rules to rescue a friend; Spock would have gladly died to preserve order. This

moral dynamic is at the center of the Star Trek universe. For Kirk, life is a universal moral that supersedes

artificial laws, even if this means discomfort to the larger group. For Spock,

the “needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few.”

As

the film progresses, these philosophies are tested beyond what either of them

could have dreamed. An act of terrorism sends the Enterprise deep into Klingon

space where they are commanded to

disobey the law by executing remotely rather than capturing the fugitive John

Harrison. Now motivated by personal revenge, Kirk is more than willing to

comply, even firing one of his closest friends who dares to challenge the

mission’s motives. The audience suspects that not everything is what it seems; the

clever Star Trek fan will begin

to pick up clues the moment Kirk is given exactly seventy-two secret torpedoes.

When the fugitive is finally confronted and revealed, well…it’s difficult to

describe, but let’s say it left a big grin on my face for the rest of the movie.

This Star

Trek adventure is both new and old, forward

thinking and nostalgic.

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers