Carl E. Olson's Blog, page 143

July 10, 2013

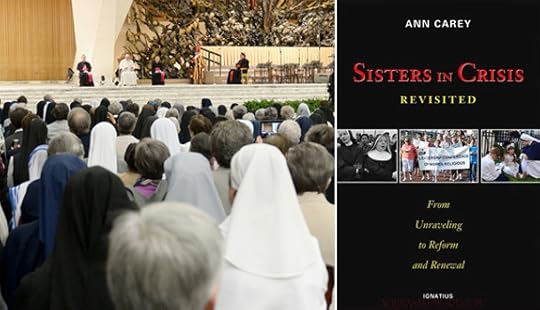

Women Religious in the U.S.: The Past Fifty Years

Women Religious in the U.S.: The Past Fifty Years

| Catherine Harmon | CWR

Ann Carey, the author of Sisters in Crisis: Revisited discusses the past, present, and future of sisters in the States

Ann Carey has

written extensively about Catholic women religious for many years,

publishing articles on the subject in the National Catholic

Register, Our Sunday Visitor, Crisis, and Catholic World

Report. She has received Catholic Press Association awards for news

and feature writing and for investigative reporting. The second, updated

edition of her book Sisters in Crisis is now available from Ignatius Press, and discusses at

length the on-going controversy surrounding the Leadership Conference of

Women Religious and the group’s clashes with the Vatican. The book

also examines the dramatic changes in the lives of women religious in

the United States in the years since Vatican II, as well as the

increasingly hopeful signs of genuine renewal cropping up in religious

communities across the country.

Carey recently discussed Sisters in Crisis: Revisited—From Unraveling to

Reform and Renewal with CWR managing editor Catherine

Harmon.

CWR: The first edition of this

book was published in 1997. Since then, we’ve seen the launch of

the Vatican’s apostolic visitation of US women religious

communities as well as the Congregation for the Doctrine of the

Faith’s doctrinal assessment of the Leadership Conference of

Women’s Religious. Is the “crisis” faced by

today’s women religious the same one they faced in 1997? Would you

say their overall situation has improved or worsened since that time?

Religion and Worldly Success

Religion, Liberalism, and Worldly Success | James Kalb | Catholic World Report

The irony of modern liberalism is that it is made possible by ties and loyalties that it rejects and destroys.

Why does it seem that orderly, prosperous, and well-run societies are usually less religious, but the less religious a society becomes the more disorderly it gets?

The situation is complex, it’s hard to do comparisons, and polling results are subject to a great deal of interpretation, but general trends seem clear. Northern and Western European countries are irreligious, Northeast Asian countries such as China and Japan are irreligious, and communist and post-communist countries are irreligious, except where religion was part of resistance to foreign ideological domination. In contrast, less developed areas such as Africa, South America, and Asia outside the Russian and Chinese cultural spheres are usually quite religious.

Given all that, it seems clear that religion doesn’t mix with success or modernization, right?

Actually, the picture is more complicated than that. It does appear that more order and prosperity mean less religion. That should be no surprise: people have been saying for some time that there are no atheists in foxholes and the poor are closer to God. It’s also true that the trend throughout the world seems to be away from religion. On the other hand, it’s equally true that less religion means less order and prosperity. Kill a country’s religion, and you kill the country. Throughout the West the post-60s period has been marked not only by a trend toward extreme secularity, but by an end to the postwar boom and by intractable social problems, including radical increases in crime and family instability.

To explain the situation we need to look at the relation between religion and social order.

July 8, 2013

New: "The Transforming Power of Faith: Wednesday Audiences" by Benedict XVI

Now available from Ignatius Press:

The Transforming Power of Faith: Wednesday Audiences

by Benedict XVI

"Having faith in the Lord is not something that involves solely our

intelligence, the area of intellectual knowledge; rather, it is a change

that involves our life, our whole self: feelings, heart, intelligence,

will, corporeity, emotions, and human relationships. With faith

everything truly changes."

So Pope Benedict XVI introduced his catecheses for the Year of Faith, a

series of sixteen talks given at his weekly audience from October 2012

to the end of his papacy in February 2013.

These talks explore how and

why faith is relevant in the contemporary world. How can we come to

certainty about things that cannot be calculated or scientifically

confirmed? What does God's revelation mean for our daily lives? How can

the hunger of the human heart be fulfilled?

Offering the guidance of

biblical exegesis, pastoral exhortation, and brotherly encouragement,

Pope Benedict seeks to answer these questions and many others.

"Terrapin" is "a Catholic mystery" that "offers less genre writing than art"

Terrapin: A Mystery (also in electronic book format)

By

T.M. Doran

Ignatius

Press, 2012

392

pp., $19.95

ISBN:

978-1-58617-721-8

Reviewed

by Kenneth Colston

From

the July/August 2013 issue of St. Austin Review. Learn more or

subscribe to StAR at www.staustinreview.com

Is

there such a genre as the Christian mystery? W.H. Auden, who

considered himself a Christian, thought that the “detective story”,

to which he said he was addicted as a man might be addicted to

tobacco or alcohol, was partially isomorphic with the Christian

story: it begins in a closed milieu of innocence, is disturbed by a

crime against god and society, and is restored to a

garden of

garden of

innocence by a celibate in a state of grace. This dramatic arc, Auden

maintains, is also that of Aristotelian tragedy, moving from a

peaceful state (false innocence), to murder (revelation of presence

of guilt), false clues (false location of guilt), solution (location

of real guilt), arrest (catharthis), and back to peaceful state (true

innocence). It includes a “double peripeteia”, or two reversals

of fortune, one from apparent guilt to innocence (the suspects), and

one from apparent innocence to guilt (the murderer). auden’s short

but seminal analysis, “The Guilty Vicarage” (Harper’s

Weekly,

May 1948) exposes five elements of the mystery genre as a way of

shedding light on the function of mystery versus the function of art,

which true detective stories, he insists, are not.

The

first element is the milieu, the closed society in a state of grace:

the groves of academe, the country village, the bourgeois train car

or drawing room—not, however, a monastery, because the requirement

of confession threatens exposure and undermines innocence, which may

be why, Auden speculates, detective stories flourish more in

predominantly Protestant countries. the second element, the victim,

must be someone who is bad enough to involve everyone in suspicion

but good enough to make everyone feel guilty: “the best victim is

the negative Father or Mother Image”. The third element is the

murderer, “the rebel who claims the right to be omnipotent”,

through concealed “demonic pride”, and whose execution, in a

satisfying mystery, is “an act of atonement”. The fourth element,

the suspects, are guilty not of the murder but of something real that

they wish to hide: crimes against God and neighbor or against God

alone, a “hybris of intellect or innocence”, a lack of faith in

another suspect. The fifth element is the detective, and Auden says

that there have only been three completely satisfactory ones, each of

which embodies a perennial type: Sherlock Holmes, the scientific

seeker of neutral truth; Inspector French, the Scotland Yard yeoman

whose dutiful sacrifice on behalf of society is total; and Father

Brown, whose compassionate care of souls is paramount. These five

elements appeal to a class of readers immune to most escape

literature, doctors, lawyers, artists, scientists, or other

professionals who “suffer from a sense of sin”, which “means to

feel guilty at there being an ethical choice to make, a guilt which,

however ‘good’ I may become, remains unchanged. As St. Paul says,

‘except I had known the law, I had not known sin.’ ... The

phantasy, then, which the detective story addict indulges is the

phantasy of being restored to the Garden of Eden, to a state of

innocence, where he may know love as love and not as the law.”

I

draw upon Auden because I found it curious that Ignatius Press, known

mainly for its service to orthodox Roman Catholic readers of

theology, would be publishing a whodunit, and that StAR,

whose

mission is to reclaim the culture for the church, would wish the book

reviewed. Is there an inherent relationship between Christianity and

mystery writing? Both obviously search for justice and truth, but is

there a deeper relationship?

Terrapin

conforms

to some of Auden’s strict categories, but also, as Auden says of

Raymond Chandler, offers less genre writing than art. The setup is

simple but arresting. Four men who have been best buddies since

childhood reunite for a weekend and a Detroit Tigers baseball game.

They drink a little too much after the game; the next morning, three

of them wake up in their hotel room to find the fourth dead. Rather

than report it immediately to the police, they discuss what to do

over breakfast, and when they return to the room the body is gone.

Was their friend Greg Pace really dead, or was he playing a trick?

The central consciousness is not a detective but a mystery writer,

Dennis Cole, one of the four, and through his point of view the

entire novel moves back and forth between the hours and days

following the possible crime and vivid flashbacks to the friends’

1960s and 1970s not-so-innocent childhood spent in Terrapin Township,

a crabgrass suburb of Detroit.

The

portrait of this closed milieu of only apparent innocence, the

working-class neighborhood, is the strongest embodiment of Auden’s

theory and the greatest achievement of Doran’s creation. Auden

writes that the natural milieu should be “the Great Good place; for

the more Eden-like it is, the greater the contradiction of murder.

The country is preferable to the town, a well-to-do neighborhood (but

not too well-to-do or there will be a suspicion of illgotten gains)

than the slum.” Terrapin is peopled with memorable, good but flawed

or problem-plagued characters who are known to the neighborhood:

Dennis’ father T. A., a Korean War veteran, a widower, a machinist

by day and a reader of philosophy, theology, and (of course)

mysteries by night, a wise moral tolerant Atticus Finch figure; Jenny

Holm, a beautiful but disturbed and sexually frustrated unmarried

woman whose children have been taken away from her; Alvin, a black

man who marries a white woman and becomes the stepfather to a

rebellious teenager; and Greg’s and Dennis’s other companions,

Ben, Tony, and Lori, who accompany them on their increasingly

dangerous boyish adventures. These generously offered flashbacks,

which constitute the bulk of the book and slowly provide not only the

background but also the solution to the crime, have the ring of

observed artistic truth and are much richer than the present-time

mystery. The closely knit American neighborhood, when boys and girls

played kick-the-can freely in alleys and backyards and side streets,

their heads not glued to screens nor their ears plugged to speakers,

looking to the skies and observing their neighbors and creating

adventure and learning from adults and scrapes to become moral beings

through games that become less and less innocent, from digging frogs

out of muddy ponds to voyeurism and breaking and entering—this

former communio

personarum of

parenting adults and observant children, neither innocent nor

perverse, has probably become a thing of the past. With

air-conditioning and year-round storm windows and huge yards, who

overhears the secrets next door, let alone peeks in when the owners

are out or sits up with them until two in the morning when cancer

strikes? Doran depicts a lost world of communal friendship. How can

one learn to love one’s neighbor when the neighborhood has been

replaced by video games and hand-held devices and other instruments

of electronic isolation?

Nothing

in the novel is overtly or boisterously Catholic, not even the

protagonist’s religious Augustine-reading father, but it is, in a

sense, a Catholic mystery, with a twinge of Jansenism in the

understanding of the sinful soul that lies habitually, holds grudges

indefinitely, envies goodness constantly, retains guilt endlessly,

and plots revenge methodically. But just a twinge, for grace can be

brought out even of murder.

Kenneth

Colston is a retired teacher of languages who resides in St. Louis.

His articles have appeared in New

Oxford Review, LOGOS: a Journal of Catholic Thought and Culture,

Commonweal, Catholic Digest, Homiletic and Pastoral Review,

and many secular newspapers and journals.

From

the July/August 2013 issue of St. Austin Review. Learn more or

subscribe to StAR at www.staustinreview.com

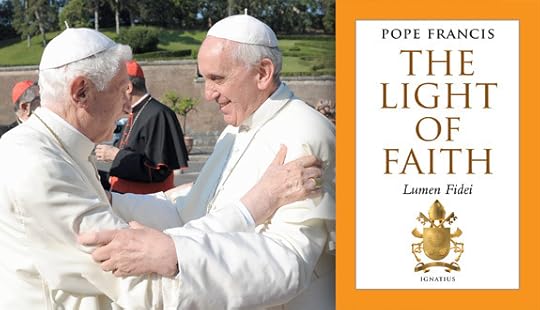

Throwing Down the Gauntlet of Faith

Throwing

Down the Gauntlet of Faith | Carl E. Olson | Editorial for Catholic World Report

The uniquely penned encyclical "Lumen fidei" is about the light of faith, as well as divine life, true love, and absolute truth

“The

future is made wherever people find their way to one another in

life-shaping convictions. And a good future grows wherever these

convictions come from the truth and lead to it.” — Joseph

Cardinal Ratzinger,

Preface

to the Second Edition (2004) of Introduction

To Christianity

“Faith

by its specific nature is an encounter with the living God—an

encounter opening up new horizons extending beyond the sphere of

reason. But it is also a purifying force for reason itself. From

God's standpoint, faith liberates reason from its blind spots and

therefore helps it to be ever more fully itself. Faith enables reason

to do its work more effectively and to see its proper object more

clearly.” — Benedict XVI,

Deus Caritas Est

There

have already been some

fine overviews written about Lumen

fidei (“The Light of Faith”),

the co-authored and unique encyclical released by Pope Francis on

July 5th,

but written largely in the months prior by his predecessor, Benedict

XVI. Rather than trying to summarize a document that deserves to be

read in its entirety, or to provide a “greatest hits” list, I

will content myself in making a few loosely related points about the

text that might be of interest to readers, especially those (again,

hint!) who have or will read it in full.

Pope

Francis notes that Benedict XVI “had almost completed a first draft

of an encyclical on faith. For this I am deeply grateful to him, and

as his brother in Christ I have taken up his fine work and added a

few contributions of my own” (7). My impression is that the vast

majority of the encyclical came from Benedict's pen. That said, the

passages by Francis are fairly obvious, but rarely in a disconcerting

or jarring fashion; quite the contrary. There are moments of

repetition, which are likely meant to be points of reiteration but

sometimes are simply repetitive. That is a minor quibble, for Lumen

fidei is a strong and challenging

document that has some exceptional and even surprising passages. This

text is like a gauntlet of faith that has been thrown down in the

midst of a confused and deeply wounded world with a combination of

humility, love, and exhortatory firmness.

Granted,

those of us who love reading theological texts can sometimes get

carried away in reacting to them. I understand that many Catholics

won't bother to read the encyclical, and I know the larger world, if

it pays attention at all, will simply try to find the “controversial

passages.” That's sad, but predictable, and that's all I'll say

about that at the moment.

As

I read Lumen fidei,

I was struck by the many passages that drew upon themes and insights

found in several of Ratzinger's book, going back to his Introduction

to Christianity, but also including

Spirit of the Liturgy

and Daughter Zion,

as well as his first encyclical, Deus

Caritas Est. Although it has the

name of Francis on it, the text bears the theological and stylistic

imprint of Ratzinger, and it to Francis' everlasting credit that he

so humbly and warmly presented it as he did.

In

addition to the specific, previous works, there is a heavily

Johannine, Augustinian quality to the encyclical.

The Encyclical on Faith

The Encyclical on Faith | Fr. James V. Schall, S.J. | CWR

"Lumen Fidei" is a quiet new force in the world for those who seek God, truth, goodness, and salvation

“There

is no human experience, no journey of man to God, which cannot be

taken up, illuminated and purified by this light. The more Christians

immerse themselves in the circle of Christ’s light, the more

capable they become of understanding and accompanying the path of

every man and woman toward God.” — Pope

Francis, Lumen Fidei, 35.

“These

considerations on faith—in continuity with all that the Church’s

magisterium has propounded on this theological virtue—are meant to

supplement what Benedict XVI had written in his first encyclical

letters on charity and hope. He himself had almost completed a first

draft of an encyclical on faith. For this I am deeply grateful to

him, and as his brother in Christ I have taken up his fine work and

added a few contributions of my own. The Successor of Peter,

yesterday, today, and tomorrow, is always called to strengthen his

brothers and sisters in the priceless treasure of that faith which

God had given as a light for humanity’s path.” — Pope

Francis, Lumen Fidei, 7.

I.

It has

long been known that Benedict XVI was working on a third encyclical,

one on faith, in the years after completing Spe Salvi, his

great encyclical on hope (still the JVS favorite!). Benedict had

designated this year as that of faith. He had given several general

audiences on the topic before he resigned. So it is both a gracious

and profound thing for his successor, Pope Francis, to take up what

Benedict had mostly completed to add his own touches to it. Nothing

makes the point of the unity of faith over time and background as

resident in the Chair of Peter more clearly than this collaboration

of two popes. Though Pope Francis has shown himself quite capable of

citing learned authors with the best of them, we know that when

something begins with Nietzsche, then cites Dostoyevsky, Martin

Buber, Dante, Romano Guardini, Ludwig Wittgenstein, T. S. Eliot, and

Newman along the way, not to mention numerous fathers of the Church,

especially Augustine, and heavy German footnotes, that we see the

hand of Benedict. The only thing missing was a quotation from Plato.

What

struck me about this latest encyclical was how little it addressed

itself to current events. It does say that marriage is between one

man and one woman for their good and that of the child, but that is

nothing new. One would think that a Church that wanted to be

“relevant,” with a new Pope, some greater effort would be made to

speak of economics and foreign affairs. I can imagine the editorial

writers in the world press and media scratching their collective

heads trying to figure out how to deal with this obviously important

document. They are not used to being told that they cannot explain

the condition of their own souls without the faith that addresses

itself to the whole of human existence.

I suggest

that the encyclical’s purposeful indifference to such things is

precisely its point. In the long run, these worldly things are not

particularly important if they are not also taken up with the great

drama of faith that constitutes salvation history. We cannot explain

ourselves by ourselves to ourselves. “Idols exist, we begin to see,

as a pretext for setting ourselves at the center of reality and

worshiping the work of our own hands. Once man has lost the

fundamental orientation that unifies his existence, he breaks down

into the multiplicity of his desires…” (13). This encyclical

spells out the alternative to the self-centered man. We are not the

center of our own reality; yet, we really exist and there is a

center.

The faith

informs us about the communion within the Godhead, the Father, the

Son, and the Spirit. The one God is Triune.

July 6, 2013

Proclaiming the Kingdom in the splendor of the Son

A Scriptural Reflection on the Readings for Sunday, July 7, 2013, the Fourteenth Sunday in

Ordinary Time | Carl E. Olson

Readings:

• Is 66:10-14c

• Ps 66:1-3, 4-5, 6-7, 16, 20

• Gal 6:14-18

• Lk 10:1-12, 17-20

Anyone who has seen a sunrise from a

viewpoint overlooking a grand vista knows the wonder of seeing the

contours of the earth revealed as the light washes over the landscape

and chases away the shadows. A world once dark and confining becomes

bright and expansive, and a sense of direction and place is

enlivened.

In an analogous, but much more profound

way, the Transfiguration of the Lord (Lk. 9:28-36) was the light that

revealed to the disciples a world bright and expansive. It gave them

a brief but life-changing glimpse into the splendor of the kingdom of

God. “At His Transfiguration,” wrote St. Thomas Aquinas, “Christ

showed his disciples the splendor of His beauty, to which He will

shape and color those who are His…”

What does this have to do with today’s

Gospel? A great deal, for everything that happened after the

Transfiguration and led up to Christ’s Passion was illuminated and

touched by the glory seen by Peter, James, and John. And while those

three apostles kept silent about what they saw (Lk. 9:36), the

Evangelist Luke wanted his readers to understand the landscape of

Jesus’ journey to Jerusalem in the light of that glorious event.

When Jesus appointed seventy-two men

(or seventy, depending on the translation), he deliberately patterned

his action after the selection of seventy elders by Moses. Those men

were meant to share in the spirit given to Moses so that, as God told

Moses, “they may share the burden of the people with you” (Num.

11:16-17). Earlier, Jesus had given the Twelve “power and

authority” over demons and illness, then sent them to proclaim the

kingdom of God and to heal the sick (Lk. 9:1-6). Some of the Church

fathers understood this as an establishment of apostolic authority,

whereas the selection of the seventy pointed toward the establishment

of the priesthood, for priests are co-workers who assist the bishops

in their duties (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 886, 939).

But this action not only foreshadowed

the priesthood, it revealed even further the prophetic, missionary

character of Jesus’ work. Sent to proclaim the presence of the

kingdom of the God, the disciples were given strict, even ascetic,

directives: carry no money, carry no sandals, greet no one along the

way. They were exhorted to elicit a response, a decision for or

against Jesus and his message. “Jesus’ own understanding of his

and his followers’ identity,” explains N.T. Wright in Jesus

and the Victory of God (Fortress Press, 1996), “went far beyond

the picture of a teacher of miscellaneous truths or maxims. The

corporate identity of the new movement belonged firmly within the

world of Jewish eschatological expectations.”

The kingdom of God is the fulfillment

of those expectations about the meaning of history and God’s plan

for mankind—and the Church is “the seed and beginning of this

kingdom” (CCC, 567, 669). Christ established the kingdom by his

preaching and his Passion, and he entrusted the message of the

kingdom to the Twelve and to the Church so it would grow and so it

could be seen for those with eyes to see. “In the word, in the

works, and in the presence of Christ, this kingdom was clearly open

to the view of men” (Lumen Gentium, 5).

But men will only see it if they turn

toward the light of the Lord, humbling gazing, if you will, upon the

Transfiguration so they might be transformed. This transformation,

St. Paul told the Galatians, comes by the way of “the cross of our

Lord Jesus Christ,” which brings about a new creation. Paul’s

blessing—“Peace and mercy to all who follow this rule”—was a

direct continuation of the peace granted to those who accepted the

disciples sent forth by Jesus: “Peace to this household.”

And every household that accepts Jesus

is taken into the household of God, the Church, which Paul called

“the Israel of God.” Within it, a world once dark and confining

becomes bright and expansive.

(This "Opening the Word" column originally appeared in the July 4, 2010, edition of Our Sunday Visitor newspaper.)

July 5, 2013

New from Ignatius Press: "Sisters in Crisis: Revisited"

Now available:

Sisters in Crisis: Revisited | From Unraveling to Reform and Renewal

Sisters in Crisis: Revisited | From Unraveling to Reform and Renewal

by Ann Carey

Fifty years ago, nearly 200,000 religious sisters worked in Catholic

schools, hospitals and other institutions throughout the United States.

American Catholics honored these women of faith who founded and built

these flourishing works of mercy.

Then came the ideological shifts and moral upheavals of the 1960s, and

ever since, most women's orders in the United States have been in a

state of crisis. Now the sisters are aging, with fewer and fewer younger

women to take their place. Perhaps related to this demographic shift is

the continuing doctrinal confusion that has come under the scrutiny of

the Vatican.

Using the archival records of the Leadership Conference of Women

Religious and other prominent groups of sisters, journalist and author

Ann Carey shows how feminist activists unraveled American women's

religious communities from their leadership positions in national

organizations and large congregations. She also explains the recent and

necessary interventions by the Vatican.

After examining the many forces that have contributed to the crisis,

Carey reports on a promising sign of renewal in American religious life:

the growing number of young women attracted to older communities that

have retained their identity and newly formed, yet traditional,

congregations.

Ann Carey is a veteran journalist who specializes in

bioethics and Catholic women religious. Her work has been published

widely in periodicals such as Our Sunday Visitor, National Catholic Register, Crisis, and Catholic World Report.

She has received Catholic Press Association awards in news and feature

writing as well as investigative reporting, and has taught writing and

journalism at the college level. Ann and her husband live in South Bend,

Indiana, where they enjoy the company of their children and

grandchildren.

"Ann Carey has documented in detail the almost unbelievable

deconstruction of communities of women religious in the United States -

the sudden transformation of so many sisters from exemplary piety and

strict observance of rules to ideologically driven political activists

determined to "restructure" the Church. Can recent efforts at the

highest levels of the Church restore what was lost? Can the "still small

voice" of revitalized and vigorous faith in the newer, growing (and

younger) religious communities replace what has been systematically

destroyed? We earnestly hope that Carey's careful account of what

happened and how will aid in finding the profoundly needed cure for this

devastating disease."

-Helen Hull Hitchcock, Women for Faith & Family

"Carey shows how the LCWR's reconfiguring of its governance structures

along with its changing theological agenda has consistently brought it

into conflict with church officials. Thus, this book becomes a must-read

for anyone seeking to understand the implications of its redirection

and the impact this has had on vowed religious life in the United

States."

-Dolores Liptak, RSM, PhD, Sisters of Mercy of the Americas, West Hartford, CT

Summary of the Encyclical, "Lumen Fidei"

Vatican City, 5 July 2013 (VIS) – Published below is a broad summary of Pope Francis' first encyclical, “Lumen Fidei”, published today, 5 July 2013 and signed on 29 June of the same year.

Lumen fidei – The light of faith (LF) is the first Encyclical signed by Pope Francis. Divided into four chapters, plus an introduction and a conclusion, the Pontiff explains that the Letter supplements Benedict XVI’s Encyclicals on charity and hope, and takes up the “fine work” carried out by the Pope Emeritus, who had already “almost completed” the Encyclical on faith. The Holy Father has now added “further contributions” to this existing “first draft”.

The introduction (nos. 1-7) of LF illustrates the motivations at the basis of the document: firstly, it reiterates the characteristics of light typical of faith, able to illuminate all man’s existence, to assist him in distinguishing good from evil, especially in this modern age in which belief is opposed to searching and faith is regarded as an illusion, a leap into the void that impedes man’s freedom. Secondly, LF – precisely in this Year of Faith, 50 years following the Second Vatican Council, a “Council on faith” – seeks to reinvigorate the perception of the breadth of the horizons faith opens so that it might be confessed in unity and integrity. Indeed, faith is not a condition to be taken for granted, but rather a gift from God, to be nurtured and reinforced. “Who believes, sees”, the Pope writes, since the light of faith comes from God and is able to illuminate all aspects of man’s existence: it proceeds from the past, from the memory of Jesus’ life, but also comes from the future as it opens up vast horizons.

Chapter One (nos. 8-22): We have believed in love (1 John 4: 16). Referring to the biblical figure of Abraham, in this chapter faith is explained as “listening” to the word of God, the “call” to come out from the isolated self in order to open oneself to a new life and the “promise” of the future, which makes possible the continuity of our path through time, linked so closely to hope. Faith also has a connotation of “paternity”, because the God who calls us is not a stranger, but is God the Father, the wellspring of the goodness that is at the origin of and sustains everything. In the history of Israel, faith is opposed to idolatry, which man is broken down in the multiplicity of his desires and “his life story disintegrates into a myriad of unconnected instants”, denying him the time to await the fulfilment of the promise. On the contrary, faith is trust in God’s merciful love, which always welcomes and forgives, and which straightens “the crooked lines of our history”; it is the willingness to allow oneself to be transformed anew by “God’s free gift, which calls for humility and the courage to trust and to entrust; it enables us to see the luminous path leading to the encounter of God and humanity, the history of salvation” (no. 14). And herein lies the “paradox” of faith: constantly turning to the Lord gives humanity stability, liberating us from idols.

LF then turns to the figure of Jesus, the mediator who opens to us to a truth greater than ourselves, the manifestation of God’s love that is the foundation of faith: “in contemplating Jesus’ death … faith grows stronger”, as in this He reveals His unshakeable love for mankind. His resurrection renders Christ a “trustworthy witness”, “deserving of faith”, through Whom God works truly throughout history, determining its final destiny. But there is a “decisive aspect” of faith in Jesus: “participation in His way of seeing”. Faith, indeed, looks not only to Jesus but also from Jesus’ point of view, with His eyes. The Pope uses an analogy to explain that, just as how in our daily lives we place our trust in “others who know better than we do” – the architect, the pharmacist, the lawyer – also for faith we need someone who is reliable and expert “where God is concerned” and Jesus is “the one who makes God known to us”. Therefore, we believe Jesus when we accept his Word, and we believe in Jesus when we welcome Him in our life and entrust ourselves to Him. Indeed, his incarnation ensures that faith does not separate us from reality, but rather helps us to grasp its deepest meaning. Thanks to faith, man saves himself, as he opens himself to a Love that precedes and transforms him from within. And this is the true action of the Holy Spirit: “The Christian can see with the eyes of Jesus and share in His mind, His filial disposition, because he or she shares in his love, which is the Spirit” (no.21). Without the presence of the Spirit it is impossible to confess the Lord. Therefore “the life of the believer becomes an ecclesial existence”, since faith is confessed within the body of the Church, as the “concrete communion of believers”. Christians are “one” without losing their individuality and in the service of others they come into their own. Thus, “faith is not a private matter, a completely individualistic notion or a personal opinion”, but rather “it comes from hearing, and is meant to find expression in words and to be proclaimed”.

Chapter Two (nos. 23-36): Unless you believe, you will not understand (Is 7:9). The Pope shows the close link between faith and truth, the reliable truth of God, His faithful presence throughout history. “Faith without truth does not save”, writes the Pope; “It remains a beautiful story, the projection of our deep yearning for happiness”. And nowadays, given “the crisis of truth in our age”, it is more necessary than ever before to recall this link, as contemporary culture tends to accept only the truth of technology, what man manages to build and measure through science, truth that “works”, or rather the single truths valid only for the individual and not in the service of the common good. Today we regard with suspicion the “Truth itself, the truth which would comprehensively explain our life as individuals and in society”, as it is erroneously associated with the truths claimed by twentieth-century forms of totalitarianism. However, this leads to a “massive amnesia in our contemporary world” which – to the advantage of relativism and in fear of fanaticism – forgets this question of truth, of the origin of all – the question of God. LF then underlines the link between faith and love, understood not as “an ephemeral emotion”, but as God’s great love which transforms us within and grants us new eyes with which we may see reality. If, therefore, faith is linked to truth and love, then “love and truth are inseparable”, because only true love withstands the test of time and becomes the source of knowledge. And since the knowledge of faith is born of God’s faithful love, “truth and fidelity go together”. The truth that discloses faith is a truth centred on the encounter with Christ incarnate, Who, coming among us, has touched us and granted us His grace, transforming our hearts.

At this point, the Pope begins a broad reflection on the “dialogue between faith and reason”, on the truth in today’s world, in which it is often reduced to a “subjective authenticity”, as common truth inspires fear, and is often identified with the intransigent demands of totalitarianism. Instead, if the truth is that of God’s love, then it is not imposed violently and does not crush the individual. Therefore, faith is not intransigent, and the believer is not arrogant. On the contrary, faith renders the believer humble and leads to co-existence with and respect for others. From this, it follows that faith lead to dialogue in all fields: in that of science, as it reawakens the critical sense and broadens the horizons of reason, inviting us to behold Creation with wonder; in the interreligious context, in which Christianity offers its own contribution; in dialogue with non-believers who ceaselessly search, who “strive to act as if God existed”, because “God is light and can be find also by those who seek him with a sincere heart”. “Anyone who sets off on the path of doing good to others is already drawing near to God”, the Pope emphasizes. Finally, LF speaks about theology and confirms that it is impossible without faith, since God is not a simple “object” but rather the Subject who makes Himself known. Theology is participation in the knowledge that God has of Himself; as a consequence theology must be placed at the service of Christian faith and the ecclesial Magisterium is not a limit to theological freedom, but rather one of its constitutive elements as it ensures contact with its original source, the Word of Christ.

Chapter Three (nos. 37- 49): I delivered to you what I also received (1 Cor 15:3). This chapter focuses entirely on the importance of evangelization: he who has opened himself to God’s love cannot keep this gift for himself, writes the Pope. The light of Jesus shines on the face of Christians and spreads in this way, is transmitted by contact like a flame that ignites from another, and passes from generation to generation, through the uninterrupted chain of witnesses to the faith. This leads to a link between faith and memory as God’s love keeps all times united, making us Christ’s contemporaries. Furthermore, it is “impossible to believe on our own”, because faith is not “an individual decision”, but rather opens “I” to “we” and always occurs “within the community of the Church”. Therefore, “those who believe are never alone”, as he discovers that the spaces of the self enlarge and generate new relations that enrich life.

There is, however, “a special means” by which faith may be transmitted: the Sacraments, in which an “incarnate memory” is communicated. The Pope first mentions Baptism – both of children and adults, in the form of the catechumenate – which reminds us that faith is not the work of an isolated individual, an act that may be carried out alone, but instead must be received, in ecclesial communion. “No-one baptizes himself”, explains LF. Furthermore, since the baptized child cannot confess the faith himself but must instead be supported by parents and godparents, the “cooperation between Church and family” is important. Secondly, the Encyclical refers to the Eucharist, “precious nourishment for faith”, an “act of remembrance, a making present of the mystery”, which “leads from the visible world to the invisible”, teaching us to experience the depth of reality. The Pope then considers the confession of the faith, the Creed, in which the believer not only confesses faith but is involved in the truth that he confesses; prayer, Our Father, by which the Christian learns to see through Christ’s eyes; the Decalogue, understood not as “a set of negative commands” but rather as “concrete directions” to enter into dialogue with God, “to be embraced by His mercy”, the “path of gratitude” towards the fullness of communion with God. Finally, the Pope underlines the there is one faith because of the “oneness of the God who is known and confessed”, because it is directed towards the one Lord, who grants us “a common gaze” and “is shared by the whole Church, which is one body and one Spirit”. Therefore, given that there is one faith alone, it follows that is must be confessed in all its purity and integrity: “the unity of faith is the unity of the Church”; to subtract something from faith is to subtract something from the veracity of communion. Furthermore, since the unity of faith is that of a living organism, it is able to assimilate all it encounters, demonstrating itself to be universal, catholic, illuminating and able to lead all the cosmos and all history to its finest expression. This unity is guaranteed by the apostolic succession.

Fourth chapter (nos. 50-60): God prepares a city for them (Heb 11:16) This chapter explains the link between faith and the common good, which leads to the creation of a place in which men and women may live together with others. Faith, which is born of the love of God, strengthens the bonds of humanity and places itself at the service of justice, rights and peace. This is why it does not distance itself from the world and is not unrelated to the real commitments of contemporary man. On the contrary, without the love of God in which we can place our trust, the bonds between people would be based only on utility, interests and fear. Instead faith grasps the deepest foundation of human relationships, their definitive destiny in God, and places them at the service of the common good. Faith “is for all, it is a common good”; its purpose is not merely to build the hereafter but to help in edifying our societies in order that they may proceed together towards a future of hope.

The Encyclical then considers those areas illuminated by faith: first and foremost, the family based on marriage, understood as a stable union between man and woman. This is born of the recognition and acceptance of the goodness of sexual differentiation and, based on love in Christ, promises “a love for ever” and recognises love as the creator that leads to the begetting of children. Then, youth; here the Pope cites the World Youth Days, in which young people demonstrate “the joy of faith” and their commitment to live faith solidly and generously. “Young people want to live life to the fullest”, writes the Pope. “Encountering Christ … enlarges the horizons of existence, gives it a firm hope which will not disappoint. Faith is no refuge for the fainthearted, but something which enhances our lives”. And again, in all social relations, by making us children of God, indeed, faith gives new meaning to universal brotherhood, which is not merely equality, but rather the common experience of God’s paternity, the comprehension of the unique dignity of each person. A further area is that of nature: faith helps us to respect it, to “find models of development which are based not simply on utility and profit, but consider creation as a gift”. It teaches us to find just forms of government, in which authority comes from God and which serve the common good; it offers us the possibility of forgiveness that leads us to overcome all conflict. “When faith is weakened, the foundations of humanity also risk being weakened”, writes the Pope, and if we remove faith in God from our cities, we will lose our mutual trust and be united only by fear. Therefore we must not be ashamed to publicly confess God, because faith illuminates social life. Another area illuminated by faith is that of suffering and death: Christians are aware that suffering cannot be eliminated, but it may be given meaning; it can be entrusted to the hands of God who never abandons us and therefore become “a moment of growth in faith”. To he who suffers, God does not give reasons to explain everything, but rather offers His presence that accompanies us, that opens up a threshold of light in the shadows. In this sense, faith is linked to hope. And here the Pope makes an appeal: “Let us refuse to be robbed of hope, or to allow our hope to be dimmed by facile answers and solutions which block our progress”.

Conclusion (nos. 58-60): Blessed are you who believed (Luke 1,45) At the end of LF, the Pope invites us to look to Mary, “perfect icon” of faith who, as the Mother of Jesus, conceived “faith and joy”. The Pope elevates his prayer to Maria that she might assist man in his faith, to remind us those who believe are never alone and to teach us to see through Jesus’ eyes.

Ignatius Press to Release Pope Francis' First Encyclical

'The Light of Faith' (Lumen Fidei) available soon in hardcover

'The Light of Faith' (Lumen Fidei) available soon in hardcoverSAN FRANCISCO, July 5, 2013 | Faith is the source of light, of guidance for the Christian life.

"We walk by faith, not by sight," wrote St Paul. In his highly

anticipated first encyclical, The Light of Faith (Lumen Fidei), Pope

Francis reflects on the meaning of faith, the beginning of God's

gracious salvation and the means by which man encounters the living God

through Jesus Christ in the Holy Spirit.

Ignatius Press is slated to release the

encyclical as a high-quality, hardcover, deluxe edition in August, in

time for the fall celebrations of the Year of Faith.

"Ignatius Press is honored and

delighted to publish Pope Francis' first encyclical in a special

hardcover edition and to get it before the reading public," said

Ignatius Press President Mark Brumley. "This follows what we did with

Pope Benedict's encyclicals and other works."

In The Light of Faith, Francis draws on

key themes of his predecessor, Pope Benedict XVI, who wrote encyclicals

on charity and hope. He intended to complete the set with a reflection

on faith, which would also have underscored the Year of Faith that he

launched. Benedict's history-making retirement meant he was unable to

finish his encyclical. Francis took up the task, adding his own

insights, themes and emphases to the work begun by Benedict XVI.

According to Francis, The Light of

Faith is a "four-hand document." Pope Benedict, Francis notes, "handed

it to me, it is a strong document. He did the great amount of work."

Thus, although officially The Light of Faith (Lumen Fidei) is an

encyclical of Francis' and reflects his teaching ministry, it is also

reflects the work of Pope Emeritus Benedict. It's not only Francis'

first encyclical; it is also among the few encyclicals openly

acknowledged to have been written by two successors of St. Peter.

For more information, to request review

copies or to schedule an interview with Ignatius Press President Mark

Brumley, please contact Kevin Wandra (404-788-1276 or KWandra@CarmelCommunications.com) of Carmel Communications.

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers