Carl E. Olson's Blog, page 140

July 31, 2013

Ignatius of Loyola and Ideas of Catholic Reform

Ignatius of Loyola and Ideas of Catholic Reform | Vince Ryan

How to categorize or describe

Catholic reforming activity in sixteenth century has been the subject of

intense historical debate. The term Counter-Reformation itself

presupposes that any reforming activity by the Catholic Church was in

response to the ideas and actions of the Reformation. In the nineteenth

century, the German historian, Wilhelm Maurenbrecher, began using

Catholic Reformation to describe the reforming activity within the

Church that did not arise in response to Protestantism. Pre-dating

Luther, this movement of Catholic reformers in the late fifteenth and

early sixteenth centuries sought to rectify the abuses in the Church and

thus renew its practices and mission.

A useful parallel for the early stages of this movement would be the Gregorian reforms of

the eleventh and twelfth centuries, when a group of churchmen, primarily

in response to the various clerical abuses of the time, implemented a

series of ecclesiastical reforms to eliminate the lax and sometimes

scandalous activities of the clergy and to guard against the

encroachment of secular powers upon Church offices. Those who called for

and carried out reform within the Catholic Church on the eve of the

Protestant Reformation were working within this tradition. Prominent

figures in this movement were Ximenes de Cisneros, John Colet, John

Fisher, Gasparo Contarini and even Erasmus of Rotterdam. These men

advocated reform through improved education, greater emphasis upon the

New Testament, and the good example of Church leaders. [1]

St. Ignatius of Loyola

Today most scholars agree that Catholic reforming activity in this era should

be viewed through both the Counter-Reformation and Catholic Reformation

lenses. While such revision has gained more general acceptance, various

figures of the period need to be re-examined under this enhanced

perspective. St Ignatius of Loyola is one such

individual.

While many are

familiar with the life of Ignatius, a brief recounting of his conversion

experience will be beneficial for the discussion. Born to a Basque noble

family, Ignatius was consumed by the chivalric concept as a young man

and attempted to make a reputation through military valor. Such

illusions were crushed when his leg was shattered by a cannon ball at

the siege of Pamplona in 1521. His injury left him convalescent for many

months. To pass the time, Ignatius requested a book of chivalric

romances that had delighted him so in his youth. None being found in the

castle where he was recuperating, he was brought Ludolph of Saxony's

Life of Christ and Jacopo da Voragine's lives of the saints known as

The Golden Legend. The spiritual satisfaction and peace provided

by these works gradually changed his outlook; visions of knightly glory

were now replaced by the desire to do great deeds just as the saints had

for the love of God.

When Ignatius gathered together the small group at the University of Paris who would

become the first Jesuits, their concern was not the combating of nascent

Protestantism. In fact, an initial goal of the company had been to seek

passage to the Holy Land to minister to Christians and convert the

Muslim inhabitants. Such a desire seems to indicate that these men were

somewhat oblivious to the internal problems that Christendom was facing.

But Providence did not permit such early ambitions to be fulfilled.

Ignatius and his companions went to Rome where they put themselves at

the service of Pope Paul III. The pope approved the order in 1540, and

Ignatius was chosen as the first superior general.

Ignatius's concept

of renewal was very much in keeping with the spirituality advocated by

other contemporary Catholic reformers. Whereas in the Middle Ages

religious experience was more communal and contemplative, in the

fifteenth and sixteenth centuries this experience tended to be more

individual and active. The Imitation of Christ

by Thomas a Kempis was a popular meditative tool that emphasized the individual's

relation with Jesus, particularly stressing Christ as a model even when

carrying out the most mundane tasks. Thomas a Kempis' work would

strongly influence Ignatius's own spirituality. [2]

The Jesuit

founder's most famous theological composition, the Spiritual

Exercises, a well-ordered manual of meditations, rules, and

practices culled from his own experiences, was a guide for the

Christian's journey from purgation to enlightenment to union with

Christ. A practical and ascetical handbook often used for retreats, the

Exercises reflect the shift toward interiorized and personal

spirituality. Demonstrating the active nature of this spirituality, the

Jesuits did not celebrate the Liturgy of the Hours in common or choir

for fear that this would interfere with their commitment to ministry.

These notions of interior conversion to Christ and active service in his

name would become central to Jesuit identity.

The Jesuit Agenda

Jesuit service encompassed a multitude of duties, preeminent among which was

catechesis of the young and uninformed. In an initial sketch of the

order drawn up by Ignatius and his companions in 1539 to present to Paul

III, the theme of educating the youth is quite prominent:

Whoever wishes to be

a soldier for God under the standard of the cross and to serve the Lord

alone and His Vicar on earth . . . bear in mind that he is part of a

community founded principally for the advancement of souls in the

Christian life and doctrine and for the propagation of the faith by the

ministry of the word, by spiritual exercises, by works of charity, and

expressly by the instruction in Christianity of children and the

uneducated. [3]

The emphasis on

teaching reappears in section three of the document where Ignatius

instructs future Jesuits to hold esteemed the instruction of children

and the uneducated in the Christian doctrine of the Ten Commandments and

other similar rudiments. [4] The founding of the first Jesuit institution

completely dedicated to secondary schooling for the laity at Messina in

1548 was only a natural extension of the catechetical duties Ignatius

deemed so critical to the order.

The Jesuit

university was a synthesis of social education, rhetoric and the

classics taught under the pedagogical techniques Ignatius himself had

experienced at Paris. However, as Reformation historian Michael Mullet

notes, The highest of Loyola's educational priorities, the ultimate

purpose of schooling, was piety. [5] The Constitutions of the Jesuits

stipulated that teachers should, in their courses, regularly touch upon

matters valuable for forming good habits, evangelizing and promoting

Christian living.

While the ability to

evangelize was one of many skills that Jesuits hoped to instill at their

schools, it was also one of the primary functions of the Society itself.

The early Jesuits dedicated themselves to a worldwide ministry of

evangelization. As Ignatius explained in the 1539 proposal, their goal

was to propagate the Faith, especially wherever the pope desired them,

whether he sends us to the Turks or to the New World or to the

Lutherans or to others, be they infidel or faithful. [6] It is worth noting

that missions to the Turks and the Americas were placed ahead of those

to Protestants. The reference to Lutheranism is even more striking

because it figures so rarely in the early writings of Ignatius. Noting

this absence, John W. O'Malley remarks that even in the saint's

autobiography, he scarcely mentions the Protestant

Reformation. [7]

Whence the Image of

a Counter-Reformation Leader?

And yet why have

many considered Ignatius in particular and the Jesuits in general as

hallmarks of the Counter-Reformation? The problem, in part, is due to

the debate over how to describe the reforming activity of the Catholic

Church of the time. Until the twentieth century, Counter-Reformation

was the preferred description. However, such an assessment is not due

merely to historical generalizations. After his death in 1556, Ignatius

of Loyola was regularly presented in contrast to Martin Luther, and the

Jesuits themselves were the prime culprits for this portrayal. Viewed in

the context of post Tridentine counterattacks, such a rendering is

understandable. Moreover, the military metaphors that Ignatius himself

used in much of his writing, while ultimately rooted in his previous

chivalric fascinations, corresponded nicely to the image of Ignatius and

the Jesuits as the shock troops of the

Counter-Reformation.

Of course such a

view of the Jesuits has some truth to it. Jesuits participated at Trent

(though in a more peripheral manner) and were instrumental in

implementing the decrees of the Council. Robert Bellarmine was one of

the most distinguished persons of the era with his attacks on

Protestantism and his defense of Catholic theology. Toward the end of

his life, Ignatius himself was more active in the fight against the

Lutherans. He frequently communicated with Peter Canisius, who was on

the frontlines of the conflict in Germany, about his growing awareness

for this aspect of the Society's mission. In 1550, Ignatius revised the

bull that established the Jesuits, stating that the purpose of the order

was now the defense and propagation of the

faith. [8]

Still, even taking

into account the actions of the last decade of Ignatius' life, it is

inaccurate to see Ignatius and the Jesuits as an outgrowth of the

Counter-Reformation. The spirituality, the outlook, and the purpose of

the early Jesuits are examples of a Catholic reform movement that was

not prompted by opposition to the Protestant Reformation.

End Notes:

[1] For a lucid

and detailed discussion of the historiography of this debate, see John

W. O'Malley, SJ, Trent and All That: Renaming Catholicism in the

Early Modern Era (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000).

[2] A. G. Dickens, The Counter Reformation (New York: W. W.

Norton & Co, 1968) p. 22.

[3] Document found in John C Olin, Catholic Reform from Cardinal Ximenes to the Council of Trent

1495-1563 (New York: Fordham Univerity Press, 1990) p. 83.

[4] Ibid, p. 85.

[5] Michael A Mullett, The Catholic

Reformation (London: Routledge, 1999) p. 95.

[6] Olin, p. 84.

[7] John W O'Malley, SJ, "Was Ignatius Loyola a Church

Reformer? How to Look at Early Modern Catholicism", Catholic

Historical Review, 77 (1991), p. 184.

[8]Terence O'Reilly,

Ignatius of Loyola and the Counter-Reformation: the Hagiographic

Tradition, Heythrop Journal, 31 (1990), p. 446.

This article originally appeared in the September/October 2001 issue of Catholic Dossier.

The Counter-Reformation: Ignatius and the Jesuits

The Counter-Reformation: Ignatius and the Jesuits

| Fr. Charles P. Connor | An Excerpt from

Defenders of the Faith in Word and Deed

Defenders of the faith have been raised up in every era of the Church

to proclaim fidelity to the truth by their words and deeds. Some have

fought heresy and overcome confusion like Athanasius against the Arians

and Ignatius Loyola in response to the Protestant reformers. Others have

shed their blood for the faith, like the early Christian martyrs of Rome,

or Thomas More, John Fisher and Edmund Campion in Reformation England.

Still others have endured a “dry” martyrdom like St. Philip

Howard, Cardinal Joseph Mindszenty and Jesuit Walter Ciszek. Intellectuals

have been no less conspicuous in their zealous defense of the faith, like

Bonaventure, Albert, Thomas Aquinas, or Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger. The

stories of all these,and more, are told here in Fr. Charles Connor's

Defenders of the Faith in Word and Deed. Here is the story of the

Society of Jesus.

On

On October 31, 1517, an Augustinian monk named Martin Luther, long fearful

for his own salvation, seemed to unleash tremendous personal hostility

when he nailed his famous Ninety-five Theses to the door of the cathedral

in Wittenburg, Germany. This single action has traditionally been viewed

as the beginning of the Protestant Reformation. Before it ended, several

new theologies were formulated by at least two generations of reformers,

causing Christianity to fall into centuries of division.

The term sola fide ("faith alone") is often associated with Luther.

It was a belief that provided him a great deal of inner tranquility. Once,

while meditating on Saint Paul's Letter to the Romans, Luther came to

the verse that states that "man is justified by faith apart from works

of the law." [1] Luther took this to mean that a person does not have

the capability to work out his own salvation because of his sinful human

nature. Instead, God gives his free gift of grace, which stimulates faith

and leads to salvation. Luther rejected, it appears, the admonition of

the Apostle James that faith without good works is dead, [2] preferring

to concentrate only on that which gave him inner peace.

Luther also opposed the buying and selling of indulgences, a practice

quite rampant in the western Europe of his day. The Church has always

taught that an indulgence is a remission of the temporal punishment due

to sin, and Luther correctly pointed out that such forgiveness cannot

be purchased. The abuse of selling indulgences and the erroneous attitudes

it created are well illustrated by the slogan of a preacher in Luther's

time: "Another soul to heaven springs when in the box a shilling rings."

[3]

While justification and indulgences are the issues for which Luther is best

remembered, many more grievances comprised his Wittenburg list. Some two

years after he had posted them, he confided in writing to a friend that

the idea of the Pope as the anti-Christ, once repellent to him, now seemed

to have more plausibility. Luther at first had no intention of beginning

a new ecclesial body. As he meditated on Scripture, however, he began to

think that the Church should return to the gospel in its purest form as

he envisioned it, eliminating what he regarded as unnecessary liturgical

ceremony, hierarchical structure, and the like:

For Luther everything began from his fundamental experience ...

salvation comes [to human beings] from God through faith alone. God

does everything and they do nothing. Good works do not make people good,

but once people have been justified by God they do good works.... So

Luther turned his back on everything in tradition which denied the preeminence

of scripture and faith. He rejected what appeared to him as a means,

a claim on the human side to deserve salvation: the cult of the saints,

indulgences, religious vows, those sacraments which [he could not find]

attested in the New Testament. Anything not explicitly set out in scripture

was worthless. All that counted was the universal priesthood of the

faithful. [4]

In 1520, the papal bull Exsurge formally condemned forty-one of Luther's

propositions, and he was given two months to submit to the authority of

the Church. In December 1520, he publicly burned his copy of Exsurge,

and excommunication followed one month later.

Closely akin to Luther was Ulrich Zwingli in Switzerland. A former priest

and student of the Renaissance scholar Erasmus, Zwingli was based in the

city of Zurich, having moved from Glavis, the scene of his former priestly

labors. He was, from all accounts, a more inwardly secure man than Luther.

His preoccupation was not so much his own eternal destiny as it was freeing

his disciples from the shackles of Rome's domination. Following this view

and a Lutheran disposition toward "gospel purity", reformed churches were

established in Switzerland. These congregations established vernacular liturgies,

in contrast to the Latin liturgy of the Catholic Church. They also removed

statues of the saints, secularized convents, and followed other practices

emerging in neighboring Germany.

The French layman John Calvin brought a nonclerical background to Reformation

theology and represented a younger generation of reformers. Calvin was also

based in Switzerland, though in the city of Geneva. In fact, his grave can

be seen there to this day. It consists of a single pole, atop of which are

the initials "J. C." This protrudes through some greenery and is surrounded

by a small iron fence. The grave is reminiscent of the stark nature of ecclesial

architecture in Calvinistic churches, if not the severity of Calvin's thought.

Calvin was obsessed with the sovereign nature of God. In his Institutes

of the Christian Religion, he develops the theory for which he is best

remembered: predestination. All creatures merited damnation, but God in

his mercy chose some for salvation. These, in turn, needed the vehicle of

a church in which to express their faith. Calvin's emphasis was very much

on the church as a local community of believers in whom power rested. His

unique brand of theology was gradually adopted by religious groups identified

as Presbyterians, Huguenots, Puritans, and Congregationalists. His ideas

spread quickly to England and to its colonies in North America. Also, they

found their way to Scotland in the person of John Knox, as well as the Low

Countries of Europe, Holland in particular.

In England, despite the fact that Henry VIII was given the title Defender

of the Faith by the Holy See for a book published under his name, the monarch

was anything but a theologian, and the Reformation in England was not theological

in origin. Henry's wife Catherine of Aragon gave him no male heirs. Wishing

to have his marriage annulled, but refused by the Church, he turned to the

English clergy with the same request and subsequently declared himself head

of the church in England. Henry's Six Articles, promulgated in 1539, kept

the essentials of the Catholic faith (even though failure to take the Act

of Supremacy recognizing Henry's headship of the church led most often to

execution). it was not until his death that Calvinistic theology began to

find its way into the Book of Common Prayer. When Henry's daughter Mary

Tudor became monarch in 1553, she briefly restored Catholicism and carried

out over two hundred executions of Protestant heretics. Upon the accession

of her half-sister Elizabeth (the daughter of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn),

Anglicanism was officially established as the state religion and the Thirty-nine

Articles spelled out the particulars of belief. They did not rid the Church

of England of as many vestiges of Romanism as some would have liked. It

seemed to be

a theology very close to neighbouring Calvinism which maintained

traditional forms like the episcopate and liturgical vestments. Both

Catholic and Protestant dissidents were mercilessly persecuted. [5]

The Reformation was, to be sure, no isolated event,

but a series of movements in several European countries that in varying

ways departed from Catholicism. In response to Protestantism and to the

problems it sought to address, the Catholic renewal or Counter-Reformation

became a reality. One of the magnificent fruits of that renewal was the

establishment of the Society of Jesus, founded by the Spanish Basque lgnatius

of Loyola.

Loyola is a castle at Azpeltia, located in the Pyrenees Mountains. It

was there that Iñigo, as he was then called, was born, in 1491.

His background was military, and he fought briefly against the French

in Pamplona. A serious battle injury brought him back to his native castle

and confined him for weeks. He was a worldly sort and would love to have

occupied his hours reading romantic novels. Instead, only two books, on

the lives of the saints and the life of Christ, were available. The biographies

of the saints began to fascinate him, make him think of the uselessness

of his own life up to that point, and provoked the interior question:

If such acts of spiritual heroism were possible in the lives of others,

why would they not be possible in his?

A hunger for God began to overtake him by degrees, and after a time he

resolved to go on pilgrimage to the shrine of Our Lady of Montserrat.

Sometime during the course of that visit he determined that thenceforth

he would lead a penitential life and his stay in the nearby small town

of Manresal where he experienced solitude and prayer, confirmed his desire

all the more. He made a pilgrimage to the Holy Land and then studied in

Barcelona, Alcala, and, finally, at the University of Paris, where he

received the Master of Arts in 1534. Still his fervor did not slacken.

At Paris he was to meet companions who were like-minded in spiritual outlook

and whose names would become well known in Jesuit annals: Francis Xavier

(a Spanish Basque like Ignatius), Favre, Laynez, Salmeron, Rodriguez,

Bobadilla. Together they would become "the Company", the first Jesuits,

defenders of the faith in heretical times.

On the feast of Our Lady's Assumption, August 15, 1534, these men professed

their vows in the chapel of Saint Denis on the hill of Montmartre in Paris.

They vowed to work for the glory of God. They agreed that when they finished

their studies and became priests, they would go to Jerusalem together,

but if they could not go there in a year, they would go to Rome and offer

to go anywhere the Pope deemed necessary. Their hopes of going to Palestine

would not be realized, but other needs quickly became apparent.

There being no likelihood of their being able soon to go to the

Holy Land, it was at length resolved that Ignatius, Favre, and Laynez

should go to Rome and offer the services of all to the pope, and they

agreed that if anyone asked what their association was they might answer

"the Company of Jesus", because they were united to fight against falsehood

and vice under the standard of Christ. On his road to Rome, praying

at a little chapel at La Storta, Ignatius saw our Lord, shining with

an unspeakable light, but loaded with a heavy cross, and he heard the

words, Ego vobis Romae propitius ero, "I win be favorable to

you at Rome." [6]

Eventually they became a religious order and took formal vows. The members

of the Society of Jesus, or Jesuits, truly were men of the Church. The papal

bull of institution, promulgated in 1540 during the pontificate of Pope

Paul III, stated the Society's purposes. The document "Rules for Thinking

with the Church" is also illustrative. It was composed by Ignatius himself

as an addition to his Spiritual Exercises. It represents a reply

to the Protestant challenge, affirming many long-established practices that

were under severe criticism and attack. It is a document "characterized

more perhaps by its balance and moderation than one may at first think".

[7] Rule Thirteen initially appears anything but moderate:

If we wish to proceed securely in all things, we must hold fast

to the following principle: What seems to me white, I will believe black

if the hierarchical Church so defines. For I must be convinced that

in Christ Our Lord, the bridegroom, and in His spouse the Church, only

one Spirit holds sway, which governs and rules for the salvation of

souls. For it is by the same Spirit and Lord who gave the Ten Commandments

that our Holy Mother Church is ruled and governed. [8]

In addition to absolute loyalty, Ignatius in the Constitutions leaves no

doubt that it is to be interpreted as willingness to carry out the wishes

of the Holy See:

All that His Holiness will command us for the good of souls, or

the propagation of the faith, we are bound to carry out with neither

procrastination nor excuse, at once and to the fullest extent of our

power, whether he sends us among the Turks, to the New Worlds, to the

Lutherans, or any other manner of believers or unbelievers.... This

vow may scatter 'us to the distant parts of the world. [9]

The work of the Jesuits in defending the faith must be looked at in the

context of the Counter-Reformation. The times called for a spirited defense

of faith; it was the time for Catholic renewal; the Church had been weakened

from within by the laxity of her own; she had been weakened from without

by the strong theological dissent of the various reformers. The Church had

to respond adequately, and the Jesuits found themselves part of this response.

In all manner of response, however, Ignatius was quite insistent that charity

prevail and that the integrity of the Church not suffer because of the misdeeds

or poorly contrived statements of those attempting to defend it:

Great care must be taken to show forth orthodox truth in such a

way that if any heretics happen to be present they may have an example

of charity and Christian moderation. No hard words should be used nor

any sort of contempt for their errors be shown. [10]

A man can be charitable as he clearly, unambiguously teaches Catholic truth.

This was Ignatius' aim, and education was to play a key role. If men were

adequately trained, the Church would be better served; such motivated the

opening of the Roman and German colleges in the Eternal City. The former

was established primarily though the largesse of the family of Saint Francis

Borgia, the man who would become Ignatius' successor as third General of

the Society; the latter was an educational bastion for students from all

countries affected by the Reformation.

Although an educated Jesuit was always to exercise charity, his response

to heresy must be firm and decisive. One of the truly great Jesuits to receive

instruction from Ignatius before undertaking his mission was Saint Peter

Canisius:

Once a man has been convicted of heretical impiety or is strongly

suspect of it, he has no right to any honour or riches: on the contrary,

these must be stripped from him ... If public professors or administrators

at the University of Vienna or the other universities have a bad reputation

in relation to the Catholic faith, they must be deprived of their degrees.

All heretical books must be burned, or sent beyond all the provinces

of the kingdom. [11]

Canisius' record of educational beginnings is impressive: Ingolstadt, Vienna,

Prague, Strasbourg in Alsace (where he was involved in the opening negotiations),

Innsbruck (where he introduced the Sodality of the Blessed Virgin Mary to

collegians), Dillingen, and Fribourg. In addition, he managed time at the

Council of Trent, where his very practical advice to the Council Fathers

about the Reformation in Germany was highly regarded. Strong as his defense

of Catholicism was in day-to-day relations with German Protestants, he favored

the approach of peaceful coexistence. Some saw this as betrayal, but Canisius

felt (and later convinced Rome) that a calm, firm, and educated approach

would help Catholics win an intellectual battle they had previously been

losing. All of this is not to suggest that his career was solely academically

oriented. His sojourn in Vienna proves the contrary:

Many parishes were without clergy, and the Jesuits had to supply

the lack as well as to teach in their newly-founded college. Not a single

priest had been ordained for twenty years; monasteries lay desolate;

members of the religious orders were jeered at in the streets; nine-tenths

of the inhabitants had abandoned the faith, while the few who still

regarded themselves as Catholics had, for the most part, ceased to practice

their religion. At first Peter Canisius preached to almost empty churches,

partly because of the general disaffection and partly because his Rhineland

German grated on the ears of the Viennese; but he found his way to the

heart of the people by his indefatigable ministrations to the sick and

dying during an outbreak of the plague. The energy and enterprise of

the man was astounding; he was concerned about everything and everybody,

from lecturing in the university to visiting the neglected criminals

in the jails. [12]

Such accomplishments could, no doubt, have been recounted in any of the

cities where Canisius spent any length of time. Christopher Hollis, in his

study of the Jesuits, sums up the work of this saint, now venerated as a

Doctor of the Church:

The general effect of Canisius' work was immense. He turned the

course of history. In each of the great colleges he built there were

up to a thousand students. He was the first Jesuit to enter Poland.

By 1600, there were 466 Jesuits there. When he entered Germany in 1550,

he entered with 2 Jesuits as his companions. When he left it over 30

years later there were 1,111 Jesuits at work in the country. [13]

Germany was, of course, not the only scene of the Reformation. Jesuits labored

in many countries on the Continent, and also in England. Even before the

English mission was a reality, Ignatius ordered prayers for the conversion

of England and for the English and Welsh martyrs of penal times, twenty-six

of whom had been Jesuits. Centuries later Henry Edward Manning, Cardinal

Archbishop of Westminster, himself a convert to Catholicism (and from his

tone no particular friend of the Reformation), wrote about the work of the

English Jesuits:

It was exactly what was wanted at the time to counteract the revolt

of the sixteenth century. The revolt was disobedience and disorder in

the most aggressive form. The Society was obedience and order in the

most solid compactness.... They also won back souls by their preaching

and spiritual guidance. They preached 'Jesus Christ and Him crucified'.

This had been their central message, and by it they have deserved and

won the confidence and obedience of Souls. [14]

Jesuit missionary activity was strongly influenced by two sources: Ignatius'

Spiritual Exercises and the Imitation of Christ by Thomas

a Kempis. The Society's founder tried to induce in the life of each Jesuit

a peaceful state of mind without inordinate attachments. Such inner tranquility

would help one in moments of crisis and in the major decisions of life.

With a peaceful mind, each of life's situations could be assessed in the

light of God's glory and the salvation of one's immortal soul. The Imitation

spoke to the heart of the disciple and always tried to elicit a generous

response. It is in this context that all Jesuit renewal should be judged.

British historian Thomas Macaulay, writing in grand style, captures these

grand men:

The order possessed itself once of all the strongholds which command

the public mind, of the pulpit, of the press, of the confessional, of

the academies. Wherever the Jesuit preached, the church was too small

for the audience. The name of a Jesuit on a title-page secured the circulation

of a book. It was in the ears of a Jesuit that the powerful, the noble,

the beautiful, breathed the secret history of their lives. It was at

the feet of the Jesuit that the youth of the higher and middle class

were brought up from childhood to manhood. [15]

It was to be the lot of Ignatius to spend most of his Jesuit life in Rome,

so vast an undertaking was it to direct the Society's business. He saw the

Society of Jesus grow from the original company to one thousand members

in nine countries and provinces in Europe, India, and Brazil. His death

came suddenly on July 31, 1556, in Rome. One may still see the room, along

with the adjoining quarters, where he wrote his Society's Constitutions.

His tomb is venerated in the magnificent church of the Gesù on Rome's

famous Corso Vittorio Emmanuele. His was a life lived for Christ and in

defense of his Church, or as one commentator has put it, "To gain others

to Christ he made himself all things to all men, going in at their

door and coming out at his own." [16]

Endnotes:

[1] Rom 3:28.

[2] James 2:17.

[3] Jean Comby with Diarmaid MacCulloch, How to Read Church History

(New York: Crossroad, 1991), 2:11.

[4] Ibid., 13.

[5] Ibid., 21.

[6] Herbert Thurston, S.J., and Donald Attwater, eds., Butler's Lives

of the Saints (Westminster, Md.: Christian Classics, 1988), 3:224.

[7] John C. Olin, The Catholic Reformation: Savonarola to Ignatius Loyola

(New York: Harper and Row, 1969), 202.

[8] The Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius, trans. Louis J. Puhl,

S.J. (Chicago: Loyola University Press, 1951), 160.

[9] Jean Lacouture, Jesuits: A Multibiography (Washington, D.C.:

Counterpoint, 1995), 76.

[10] Thurston and Attwater, Butler's Lives of the Saints, 3:225-26.

[11] Ignatius of Loyola to Peter Canisius, August 13, 1554, cited in Comby

and MacCulloch, How to Read Church History, 2:30.

[12] Thurston and Attwater, Butler's Lives of the Saints, 2:168-69.

[13] Christopher Hollis, The Jesuits: A History (New York: Macmillan

Com-

pany, 1968), 25.

[14] Thurston and Attwater, Butler's Lives of the Saints, 3:225.

[15] Thomas Macaulay, Essay on Von Rank's History of the Papacy,

cited in Hollis, Jesuits, 27.

[16] Thurston and Attwater, Butler's Lives of the Saints, 3:227.

Related IgnatiusInsight.com/Insight Scoop Links:

• Ignatius of Loyola and Ideas of Catholic Reform |

Vince Ryan

• When Jesuit Were Giants | Interview with Father Cornelius Michael Buckley, S.J.

• The Jesuits and the Iroquois | Cornelius Michael Buckley, S.J.

• The Tale of Trent: A Council and and Its Legacy

| Martha Rasmussen

• Reformation 101: Who's Who in the Protestant Reformation |

Geoffrey Saint-Clair

• Why Catholicism Makes Protestantism Tick | Mark Brumley

Related Ignatius Press Books:

•

St. Ignatius of Loyola | James Brodrick, S.J.

•

The Jesuit Missionaries to North America | Father François Roustang

•

The Re-formed Jesuits, Vol 2 | Joseph Becker, S.J.

•

St. Ignatius and the Company of Jesus (Vision Series) | August Derleth

•

The Word, Church and Sacrament in Protestantism and Catholicism | Fr. Louis Bouyer

Father Charles Connor is the historian of the Diocese of Scranton and

pastor at St. John the Evangelist Church, Susquehanna. He is the host of

several

programs on EWTN and author of Classic

Catholic Converts .

July 30, 2013

World Youth Day, Liturgy, and the New Evangelization

World Youth Day, Liturgy, and the

New Evangelization |

Dr. Leroy Huizenga | CWR

Well-formed disciples are shaped and

taught through good liturgy:

lex orandi, lex credendi, lex

vivendi

By the measures of attendance and

enthusiasm, World Youth Day in Rio de Janiero, Brazil, was a smashing

success, as organizers report well over three million energetic youth

on Copacabana Beach for the Saturday vigil and Sunday’s closing

Mass. World Youth Day was conceived by John Paul II as part of his

strategy for a “new evangelization,” a term he first used in 1983

in an address to Latin American bishops. As he later described in

Redemptoris Missio, a “new evangelization” or a

“re-evangelization” was needed “particularly in countries with

ancient Christian roots, and occasionally in the younger Churches as

well, where entire groups of the baptized have lost a living sense of

the faith, or even no longer consider themselves members of the

Church, and live a life far removed from Christ and his Gospel.”

From the first official World Youth Day

in Rome in 1986, then, the events have taken place not in far-flung

virgin mission fields where Christian faith has been unknown but in

cities in countries of longstanding Christian tradition where the

faith has been forgotten, among them Buenos Aires, Argentina (1987);

Czestochowa, Poland (1991); Denver, USA (1993); Manila, Philippines

(1995); Paris, France (1997); Rome (2000); Cologne, Germany (2005);

and Madrid, Spain (2011). And World Youth Days have born fruit for

the New Evangelization. Taken out of the narrow confines of Catholic

life in their particular parishes and communities and given a grander

vision of the Church universal, many younger priests, seminarians,

and religious trace their vocational discernment to their attendance

at a World Youth Day, while many younger laypeople claim to have

discovered a deeper, or even initial, conversion to the Lord and His

Church.

Mountaintop experiences do matter: they

shake youth (and adults) out of the boredom of quotidian routine. But

mountaintop experiences are not the norm, as Scripture attests; the

theophany on Mount Sinai was not enough to sustain the people for the

long term, and even after witnessing Jesus’ Transfiguration on

Mount Tabor, Peter, James, and John failed again and again.

Mountaintop experiences are not enough to sustain a person, a parish,

a Church. Indeed, one sees in the Gospels that even repeated

encounter with Jesus Christ, God incarnate, was not always enough to

sustain the disciples. But from a passage late in the Gospel of Luke,

which Pope Francis presented as part of his program for the New

Evangelization, we learn that moving from despair to courage for

mission involves an encounter with the risen Christ in the Eucharist.

The Backbone of the New

Evangelization

If encountering Christ in the Eucharist

empowers mission, liturgy matters, for the Eucharist is celebrated

and generally received in the Mass, now often called the eucharistic

liturgy. In his prepared remarks as well as his off-the-cuff

comments, Pope Francis did not mention liturgy as such. But liturgy

formed the necessary subtext of many of Francis’ remarks, given his

emphasis on the importance of mystery, the imperative of formation,

and the graces of the sacraments, especially the Eucharist. Liturgy

thus necessarily forms the backbone of the new evangelization.

July 29, 2013

The Key Themes of World Youth Day 2013

The Key Themes of World Youth Day 2013 |

William

L. Patenaude | CWR

The

words and actions of Pope Francis in Brazil built directly on the

evangelizing work of his predecessors

Two

valuable lessons came out of World Youth Day 2013. The first is that

the Holy Spirit is intent on igniting with joy and resilience the

post-conciliar Church of the twenty-first century. The second is

that, in large part due to the catechetical influences of Bl. John

Paul II and Benedict XVI, Pope Francis’s flock can better balance

the joys of the Spirit with the Cross of Christ.

It

will be helpful, then, to ponder some themes from Rio’s World Youth

Day because it is highly likely we’ll be encountering them

repeatedly as an energized Pope Francis shepherds his flock deeper

into the twenty-first century.

Go

and Make Disciples

“Where

does Jesus send us? There are no borders, no limits: he sends us to

everyone. The Gospel is for everyone, not just for some. It is not

only for those who seem closer to us, more receptive, more welcoming.

It is for everyone. Do not be afraid to go and to bring Christ into

every area of life, to the fringes of society, even to those who seem

farthest away, most indifferent. The Lord seeks all, he wants

everyone to feel the warmth of his mercy and his love.” — Pope

Francis’s closing homily,

World Youth Day, 2013.

Popes,

bishops, and even laity have said and written much during these past

few years on the New Evangelization. When planning for World Youth

Day 2013 began during the pontificate of Pope Benedict XVI the time

had come to urge the Church to act. Thus the theme “Go and make

disciples” seemed fitting for an event that draws millions of young

people and many millions more (of every age) through social media.

But

then Benedict XVI’s doctors told him that he could no longer travel

by air. And it seemed likely that even if he could he might not have

the strength that World Youth Day schedules demand. (One wonders how

much his being unable to travel to Rio de Janeiro influenced his

decision to cede the Chair of St. Peter.)

The

question of whether the pope would attend World Youth Day vanished

with the papal transition. Pope Francis brought to the world stage a

bold and gregarious personality. He changed the rules of papal

engagement and accelerated the use of social media. He continues to

bring his own style to the papacy, one that resonates in a world of

political uncertainty, economic struggle, and a growing weariness

with impersonal spirituality.

With

a stronger, younger body than his predecessor’s, Pope Francis began

charging into crowds—which, come to think of it, seems natural to

do for those who espouse an incarnational faith. Once inside the

crowds, whether in Rome or Rio or wherever, he is especially happy

when he meets those on the outskirts.

We

see the fruits of this charging

in and greeting the outskirts by

listening to those who are not at all enamored with Catholicism but

are attracted to Pope Francis.

Ars Memoria

Ars Memoria | John B. Buescher | CWR

Why would anyone think that

memorization is not a valuable part of learning?

In the 1960s, contrary to the inherited

wisdom of mankind, educators in general and Catholic educators, too,

decided that having students memorize things was a terrible notion.

If I recall, the thinking was that memorizing was a purely mechanical

operation, that it did not penetrate to the deep truth, and that it

turned out mindless robots who would uncharitably spew their mind

chaff out at opponents to distract them and protect them from being

caught by the truth.

Or something like that.

The fear of being “hypocritical”

was at work here—that great Calvinist weight that hung like an

albatross around the necks of the puritans and which they transferred

to their Progressive descendents who still demarcate the Elect and

the Damned based on worldly signs. Their acute awareness of the

difference between the outer man and the inner man made some of them

greatly aware of how debased is our state in this world, but also

made some of them greatly concerned with the evidentiary signs of

blessedness.

Some of them strove to align the inner

man with the outer one, even though they were convinced that not they

but God was the only one capable of that. Their modern Progressive

descendents gave up on that project as ultimately hopeless and

decided that the only way to achieve the alignment of the inner and

outer—to become “authentic”—was to erase the difference:

which meant accepting one’s unfashioned self not only as one’s

“natural” condition, but as one’s highest ideal. Indeed, it

sometimes seems that for Progressives “hypocrisy” is not only the

greatest sin, but perhaps the only one. It certainly seems sometimes

like the only one they are interested in convicting others of.

That affected the modern view of

pedagogy (as it did liturgical ad libbers, seeking “authenticity”).

Even losers began to receive awards because they were “great” in

and of themselves. It was reminiscent of the way in which declaring

oneself already “saved” somehow was warped to mean that no one

had to make any effort at holiness as a result.

Before, the problem was finding the

best way to bring an unformed being into alignment with the highest

wisdom offered by culture. But after Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s

ludicrously unrealistic picture of pedagogy in Émile, this

was reversed: the “highest wisdom” of the culture was judged as

a sham and a debasement that created and protected hypocrites, and

the pedagogical mission came to be seen as the destruction of that

culture in the child, so that the authentic inner man—the noble

savage—could flourish.

“Rote memorization” was a

foundational pillar of the older pedagogy, so it had to go, along

with all other methods of instilling into the child the conventional

formulations of wisdom.

July 27, 2013

The Godless Confusion and the God of Justice

Readings:

• Gn 18:20-32

• Ps 138:1-2, 2-3, 6-7, 7-8

• Col 2:12-14

• Lk 11:1-13

According

to atheist Richard Dawkins in his best-selling book The

God Delusion, the God

of the Old Testament is “arguably the most unpleasant character in

all fiction: jealous and proud of it; a petty, unjust, unforgiving

control-freak; a vindictive, bloodthirsty ethnic cleanser; a

misogynistic, homophobic, racist, infanticidal, genocidal, filicidal,

pestilential, megalomaniacal, sadomasochistic, capriciously

malevolent bully.”

That remark indicates far more familiarity with

the dictionary than with the Bible. I wonder, how much fiction has

Dawkins read? More seriously, how carefully has he actually read the

Bible?

Sadly,

Dawkins merely appeals to the tired notion that the “God of the Old

Testament” is a cruel tyrant with little love for His creation. I

suspect that even many Christians have the vague sense that such is

the case. And today’s reading from the Old Testament is the sort of

passage that can, rather easily, be misinterpreted to provide

evidence for that view.

In fact, some commentators have understood

the conversation between the Lord and Abraham about Sodom and

Gomorrah as a case of the cool-headed patriarch talking the

hot-headed deity out of rash, murderous judgment—or, as Dawkins

might put it, “an act of vindictive genocide.” But as difficult

as the text is, it actually presents something quite different: a

calm and deliberate conversation between the “Judge of all the

world”, responding to the outcry of those anguished by the deviance

practiced in those infamous cities, and the bold servant of God,

whose questions seem as much theological as personal in nature.

Far

from being petty and unjust, God was responding with patience and

love to two different but related sets of questions. The first, as

noted, came from those inhabitants of Sodom and Gomorrah crying out

for justice, apparently due to a combination of sexual immorality and

social inequality (Gen 19:4-11; Ez 16:46-51). God did not intend to

simply destroy the cities and all

of their inhabitants. Rather, as in the days of Noah, He desired to

put an end to lawlessness, yet with the knowledge that a few just men

could be found among the wicked. And so Genesis 19 depicts two angels

sent to rescue Lot and his family from the coming destruction—and

that after saving them from the advances of a lustful mob.

The

second set of questions, from Abraham, was concerned with whether or

not the Judge of all things would indeed be just. That remarkable

conversation reveals an intimacy between man and God that is unique

among ancient religious literature. “After that, once God had

confided his plan [Gen 18:17-21]” the Catechism

of the Catholic Church

notes, “Abraham's heart is attuned to his Lord's compassion for men

and he dares to intercede for them with bold confidence” (CCC

2571). Through both divine revelation and his natural intelligence,

Abraham learned what it meant to be just and compassionate. Satisfied

that God would act justly, Abraham did not stay to witness the

salvation of his relatives, but returned home (Gen 19:33).

The

intimacy between the Creator and the recipient of the Abrahamic

covenant (cf., Gen 12, 15-17; CCC 72) foreshadowed the unique

revelation about the Father given by the Son, who not only prayed to

the Father but also taught His disciples how to pray to the Father.

Luke’s account of the “Our Father,” in today’s Gospel, is

shorter than that in given by Matthew, which is the version commonly

known and said. It first acknowledges God as Father, as well as the

holiness of His name, along with the desire to see His kingdom

realized in fullness. It then asks for three basic needs, without

which man will perish, both physically and spiritually: nourishment

(“our daily bread”), forgiveness, and salvation—“do not

subject us to the final test.”

Their

heavenly Father, Jesus told the disciples, gives good gifts to those

who ask and seek with the humble, trusting heart of a child. It is a

humility and trust based in prayer and conversation with God, who is

not an unpleasant fictional character, but a caring and merciful

Father.

(This "Opening the Word" column originally appeared in the July

29, 2007, edition of Our Sunday Visitor newspaper.)

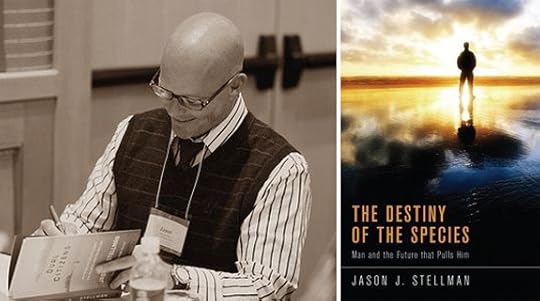

From Calvinist Prosecutor to Papist Apologist

From Calvinist Prosecutor to Papist Apologist

| David

Deavel | Catholic World Report

Convert

Jason Stellman's new old-fashioned apologetic explains that we are

“hard-wired for heaven”

Sunday,

June 21, marked the 90th anniversary of the Scopes Monkey

Trial decision. The questions surrounding evolution—meaning, in

particular, the origins of humans—still raise large and important

questions for how we understand human nature and the doctrine of

original sin. But Jason Stellman thinks that the obsession with our

physical origins, though understandable, is perhaps theologically

off-kilter. Where we've come from biologically is not as important

as where we're heading. It's not the beginning of the journey,

man—it's the destination. Stellman's The

Destiny of the Species (Wipf

and Stock, 2013) is a brief,

rollicking, and readable apologetic, notable not just for turning the

question of origins on its head, but also for pioneering a slightly

different route from the path taken by many Catholic converts in

their first books.

From Prosecutor to Papist

Stellman's

own personal story is compelling. Born and raised in Orange County,

California, Stellman came to serious faith in the context of the

Evangelicalism of the California preacher Chuck Smith's Calvary

Chapel ministries. He served as a Protestant missionary in both

Hungary and Uganda before turning to a more theologically rigorous

form of Protestantism: Calvinism. Stellman attended Westminster

Seminary in Escondido, California and began ministering in the

Presbyterian Church in America, the largest conservative Presbyterian

denomination in the U.S., planting Exile Presbyterian Church in

Woodinville, WA in 2004. Stellman's name came into the limelight

when he was chosen to serve as the chief prosecutor in the 2011

heresy trial of fellow Presbyterian minister Peter Leithart, a

Calvinist writer and scholar known to readers of journals including

First Things and

Touchstone. Leithart's

views were accused of being in line with a school of Presbyterian

thought known as the “Federal Vision,” and he was tried for,

among other charges, allegedly failing to distinguish justification

and sanctification, divine law and divine grace, and teaching that

baptism confers grace and divine adoption. In short, Leithart was on

trial for being too Catholic.

Although

Stellman's work as prosecutor was acknowledged as solid at the time,

Leithart was acquitted by the Northwest Presbytery. In the time

after this trial, however, Stellman himself began to question certain

historic Protestant beliefs like sola scriptura and

sola fide.

July 26, 2013

Celebrating World Youth Day with Ignatius Press

First World Youth Day with Our New Pope

"As you know, the principal reason for my visit to Brazil goes beyond its borders. I have actually come for World Youth Day. I am here to meet young people coming from all over the world, drawn to the open arms of Christ the Redeemer. They want to find a refuge in his embrace, close to his heart, to listen again to his clear and powerful appeal: 'Go and make disciples of all nations.'"

—Pope Francis, Arrival Address, World Youth Day 2013

Learn more about the man who reminds us of our call to go out and evangelize to all nations in one of our many Pope Francis titles:

In Him Alone Is Our Hope

The Light of Faith

Francis, Pope of a New World

Pope Francis: His Life in His Own Words

On Heaven and Earth: Pope Francis on Faith, Family, and the Church in the Twenty-First Century

Save 20% on these titles and other Pope Francis products!

Shop Now!

YOUCAT's Second Anniversary!

"Study this catechism! This is my heartfelt desire. Study this catechismus with passion and perseverance. You need to be more deeply rooted in the faith than the generation of your parents".

-Pope Benedict XVI on YOUCAT

Let our new YOUCAT: Study Guide help you fulfill Pope Benedict's desire. Aimed at helping readers to get the most out of YOUCAT, the companion study guide features 35 topics based on the catechism.

Other great titles that will deepen and enrich the faith of the young people in your life are:

YOUCAT: Youth Prayer Book

Your Questions, God's Answers

The Loser Letters

We're on a Mission from God

Save 20% on these titles and more when you shop today!

Shop Now!

St. Paul Pilgrimage Mediterranean Cruise

with Steve Ray and Ignatius Press

If Israel is where the Church was born--Turkey, Greece and Rome is where it grew up. Sail and tour the Second Holy Land with us as your escorts and guides You will not find a Saint Paul Cruise like this anywhere else. Every port is a Biblical, Catholic and St. Paul site. Don't miss the opportunity to see amazing sites while enriching your faith and nourishing your spirit.

Don't miss out, reserve your place today!

Learn More!

The Ear of the Heart Book Tour, Northern California

Come hear and meet Mother Dolores Hart in Northern California July 27-Aug. 2! Ignatius Press invites you to hear a Mother speak about the inspiring story of her glamorous life as a movie star to becoming a Benedictine contemplative nun at Regina Laudis Abbey. And, purchase an autographed copy of her best-selling new autobiography, The Ear of the Heart !

Learn More!

Free Catholic Study Bible App

Lighthouse Catholic Media and Ignatius Press have teamed up to offer the FREE Catholic Study Bible App! … now better than ever before! Packed with more content and features, this app offers the entire Catholic Bible and is available on iPhone, iPad and iPod Touch devices — and with the Android and Kindle versions coming soon! Just go to the iTunes app store and search "lighthouse bible app" and download today!

Learn More!

Last Call for This Year's Napa Institute

Catholic leaders: don't miss this year's Napa Institute, August 1-4. Join Archbishops Gomez, Chaput, Aquila, Nienstedt, Cordileone; Bishops Morlino, Vasa, Vann and Gudziak, along with Fr. Robert Spitzer, S.J., Fr. Brian Mullady, OP, Fr. Ronald Tacelli, S.J., Dr. Tim Gray, John Garvey, Mother Dolores Hart, O.S.B., Dr. Carolyn Woo, Kathryn Jean Lopez and Dr. Francis J. Beckwith. Hosted by the world-famous Meritage Resort, in the beautiful Napa Valley of California, this year's Napa Institute will explore such topics as the sanctity of work, building a Catholic culture, and reason & faith. For more information go to www.napa-institute.org or click below.

Learn More!

Catholic World Report

The Arab Springtime is a Nightmare for Syrian Christians

By Alessandra Nucci

Middle Eastern Christians decry how Western media misrepresent the increasingly violent events in Syria.

Now that Syria is in shambles—with an estimated 93,000 dead, 1.5 million refugees, and 4.5 million internally displaced; ancient churches torched, destroyed, or vandalized; Christians targeted for murder and kidnapping and even used as human shields—now the mainstream media is starting to admit that, yes, the rebel forces appear to include quite a few Islamist guerrillas...

Continue reading here

Homiletic & Pastoral Review

The Science of Divine Love

By Brent Withers

The science of divine love is measured along a dimension of intensity and depth, rather than the worldly one of quantity. With this equation, the means for our sanctification is established. All our actions, prayers, and sufferings build up the mystical body of Christ.

The human dimension works along quantity, finite pleasures, and immediate reward. The eternal dimension is one of quality, eternal treasures, and delayed reward. Quality is always superior to quantity. The growth of divine love or charity is through its intensity where we come to love God more perfectly and purely for himself....

Continue reading here

Copyright © 2013 Ignatius Press All rights reserved.

You are receiving this email because you opted in at our website www.ignatius.com

Ignatius Press

1348 10th Avenue

San Francisco, CA 94122

Forward to a Friend

Follow on Twitter

Friend on Facebook

Unsubscribe

Update Subscription Preferences

What is Social Justice? From John Paul II to Benedict XVI

What is Social Justice? From John Paul II to Benedict XVI | J. J. Ziegler | CWR

The third and final installment in a series on social justice in Catholic social doctrine

When

the Italian Jesuit Father Luigi Taparelli D’Azeglio (1793-1862) coined the term

“social justice” in the middle of the 19th century, he probably could not have

foreseen its mention in an 1894 curial document and a 1904 encyclical, nor the

importance attached to it by Pope Pius XI (1922-39) and subsequent pontiffs,

culminating in the authoritative teaching on social justice in the Catechism of the Catholic Church (1992).

After

the Catechism’s promulgation, Blessed John Paul II (1978-2005) continued to speak

about social justice. In a 1993 audience devoted to priests and politics, he said that

“Jesus formulated the precept of mutual love, which implies respect for every

person and his rights. It implies rules of social justice aiming at recognizing

what is each person’s due and at harmoniously sharing earthly goods among

individuals, families and groups.”

John

Paul taught that as priests follow the “precept of mutual love” which “implies

rules of social justice,” they must do so in different ways from the laity.

Strongly affirming the teaching of the 1971 Synod of Bishops, which was devoted

in part to justice in the world, John Paul said that

in circumstances in which there legitimately exist different

political, social and economic options, priests like all citizens have a right

to make their own personal choices. But since political options are by nature

contingent and never in an entirely adequate and perennial way interpret the

Gospel, the priest, who is the witness of things to come, must keep a certain

distance from any political office or involvement.

Quoting

the Catechism, Blessed John Paul

added that “it is not the role of the pastors of the Church to intervene

directly in the political structuring and organization of social life. This

task is part of the vocation of the lay faithful, acting on their own

initiative with their fellow citizens.”

In

his 1994 apostolic letter Tertio Millennio Adveniente, John Paul taught that social

justice has its deepest roots in creation and in the institution of the jubilee

year, described in Leviticus 25. “The

riches of Creation were to be considered as a common good of the whole of

humanity,” he wrote. “Those who possessed these goods as personal

property were really only stewards, ministers charged with working in the name

of God, who remains the sole owner in the full sense, since it is God’s will

that created goods should serve everyone in a just way. The jubilee year was meant to restore this

social justice. The social doctrine of the Church, which has always

been a part of Church teaching and which has developed greatly in the last

century, particularly after the Encyclical Rerum Novarum, is

rooted in the tradition of the jubilee year” (no. 13).

In

his 1995 post-synodal apostolic exhortation Ecclesia in Africa, John Paul called for “a serious

commitment to foster on the continent conditions of greater social justice and

good government”—or, as the Latin text literally states, “conditions of greater

social justice and the more just exercise of power”—“in order

thereby to prepare the ground for peace” (no. 117). “If you want peace, work for justice,” he

added, quoting Paul VI’s well-known statement.

Two

years later, in an address to Philippine bishops, John Paul further developed

Catholic teaching on social justice by explicitly linking social justice to the

defense of the family.

Continue reading on the CWR site.

July 25, 2013

The Role of Doctrine in Inspiring Believers to Moral Greatness

The Role of Doctrine in Inspiring Believers to Moral Greatness | Fr. Daniel Richards | HPR

In order to demonstrate this essential coexistence of nature and grace in the life of the Church, and the life of the believer, it must be shown that doctrine is necessary for salvation, not superfluous, but essential to the Church’s mission given by Christ.

St. Robert Bellarmine proposed as a mark of the true Church the

efficacy of doctrine in inspiring believers to moral greatness. That

this should be so is due to the hypostatic nature of the Church, which

is the body of Christ. Human and divine, it is necessary that members of

the Church, if they are to live in full unity with God and one another,

be transformed through that same mode of existence, inflating neither

at the expense of the other. In order to demonstrate this essential

coexistence of nature and grace in the life of the Church, and the life

of the believer, it must be shown that doctrine is necessary for

salvation, not superfluous, but essential to the Church’s mission given

by Christ. Secondly, it must also be shown that, of itself, doctrine is

inefficacious without the subjective element of faith that makes it

salvific. From the proper delineation of doctrine established by the

above, the role of the Church in proposing doctrine for belief becomes

clear. Finally, the dynamic of faith and action comes forth, by which

the believer is indeed inspired to moral greatness.

Whereas in the natural sciences, purpose is self-evident, inquiry

finding its justification in the results, the sacred sciences can seem

arbitrary to the one whose assent is demanded. What does it matter

whether Jesus Christ was God-made-man, man-made-God, or one appearing to

be the other, so long as I believe in Jesus Christ and, therefore, am

saved? Certain consequences of opposing belief can be demonstrated, but

given that there is much more we cannot know than that which we can, it

seems complete certainty will always evade us. 1 To

espouse this position does avoid the rightly eschewed narrowness of

dogmatism, but at the cost of leaving theological inquiry stunted, and

ultimately, the life of faith, short-sighted.

This work of codifying, clarifying, and amplifying doctrine is the

task of theology. Its justification, however, is not found in the

result, the action that follows inquiry. St. Thomas Aquinas addresses

this point in his Summa Theologiae. 2

It is objected that sacred doctrine is a practical science, since it is

not enough only to hear the word, but also to act upon it. While

admitting the truth of this point, St. Thomas clarifies that the action

following sacred doctrine is subordinate to the primary object which is

God. The primary concern of doctrine is not the created world, but the

uncreated God, after which it is able to treat of the created world and,

only then, have practical consequences.

Continue reading on the HPR site.

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers