Carl E. Olson's Blog, page 138

August 9, 2013

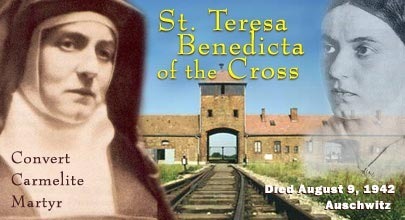

The Feast of St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross

August 9th is the Feast Day of St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross, who was martyred on that day in 1942 in the Auschwitz concentration camp.

Fr. Charles P. Connor, in Classic Catholic Converts, writes:

The story of the Jewish Carmelite Sister Teresa Benedicta of the Cross, known in the world as Edith Stein, presents us with one of the more brilliant converts to come to the Faith in [the twentieth] century; it also places us in close contact with a horrendous tragedy of the modern world, the Holocaust.

Edith Stein was born in Breslau, Germany on October 12, 1891, the youngest of eleven children. In 1913 she began studies at the University of Göttingen in Germany. She soon became a student of the phenomenologist Edmund Husserl and was later attracted to the work of Max Scheler, a Jewish philosopher who converted to Catholicism in 1920. A chance reading of the autobiography of Saint Teresa of Avila revealed to her the God of love she had long denied. She entered the Church in 1922.

For eight years Edith lived with the Dominicans, teaching at Saint Magdelene's, which was a training institute for teachers. She wrote:

Initially, when I was baptized on New Year's Day, 1922, I thought of it as a preparation in the Order. But a few months later, when I saw my mother for the first time after the baptism, I realized that she couldn't handle another blow for the present. Not that it would have killed her—but I couldn't have held myself responsible for the embitterment it would have caused.

In fact, after her conversion Edith continued to attend synagogue with her mother. Meanwhile, she continued to grow and impress as a philospher. In 1925 she met the Jesuit Erich Pryzwara, a philosopher who would have a tremendous influence on Hans Urs von Balthasar. Pryzwara encouraged Edith to study and translate St. Thomas Aquinas; she eventually wrote a work comparing Usserl with Aquinas.

In 1933 Edith entered the religious life with the Carmel of Cologne, Germany. She fell in love with the person and writing of Saint Thérèse of Lisieux. She wrote:

My impression was, that this was a life which had been absolutely transformed by the love of God, down to the last detail. I simply can't imagine anything greater. I would like to see this attitude incorporated as much as possible into my own life and the lives of those who are dear to me.

After taking her first vows, Edith was known as Sister Teresa Benedicta of the Cross. She continued to write, Fr. Connor notes, "continually developing the theme that Christ's sacrifice on the Cross and the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass are in fact one and the same sacrifice. From her religious background, she knew the importance of sacrificial prayer for Old Testament prophets." She wrote of how Jesus' sacrifice as the Incarnate God-man was the final, perfect sacrifice that replaced all of the sacrifices of the Old Testament.

Because of the rise of Nazi power, Edith and her sister Rosa, who had also converted to Catholicism, moved to Holland in 1938. On August 2, 1942, Edith and her sister were taken from the convent by two S.S. officers. She was martyred seven days later. Fr. Connor writes: "On October 11, 1998, fifty-six years, two months, and two days after her death at Auschwitz, Edith Stein, Sister Teresa Benedicta of the Cross, was canonized a saint of the Roman Catholic Church by Pope John Paul II."

Ferdinand Holböck writes in New Saints and Blesseds of the Catholic Church : 1984-1987 (Volume 2) :

The Church now presents Sister Teresa Benedicta a Croce to us as a blessed martyr, as an example of a heroic follower of Christ, for us to honour and to emulate. Let us open ourselves up for her message to us as a woman of the spirit and of the mind, who saw in the science of the cross the acme of all wisdom, as a great daughter of the Jewish people, and as a believing Christian in the midst of millions of innocent fellow men made martyrs. She saw the inexorable approach of the cross. She did not flee in fear. Instead, she embraced it in Christian hope with final love and sacrifice and in the mystery of Easter even welcomed it with the salutation,"ave crux spes unica". As Cardinal Höffner said in his recent pastoral letter, "Edith Stein is a gift, an invocation and a promise for our time. May she be an intercessor with God for us and for our people and for all people."

Books on the life and martyrdom of Edith Stein Classic Catholic Converts

Classic Catholic Converts

by Fr. Charles Connor

220 pages. Paperback. $14.95

Classic Catholic Converts presents the compelling stories of over 25 well-known converts to Catholicism from the 19th and 20th centuries. It tells of powerful testimonials to God's grace, men and women from all walks of life in Europe and America whose search for the fullness of truth led them to the Catholic Church. It is the witness of brilliant intellectuals, social workers, scientists, authors, film producers, clergy, businessmen, artists and others who, under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, studied and prayed their way into the Church. It contains a beautifully written chapter on Edith Stein.

Edith Stein: A Biography

Edith Stein: A Biography

by Waltraud Herbstrith

207 pages. Paperback. $12.95

A powerful and moving story of the remarkable Jewish woman who converted to Catholicism, became a nun, achieved remarkable success in the male-dominated world of German philosophy, and was sent to a Nazi death camp when she refused to deny her Jewish heritage.

Waltraud Herbstrith has fashioned a warm, memorable portrait of this woman who, as Jesuit philosopher Jan Nota points out in the introduction, "discovered in Christ the meaning of human existence and suffering ... Edith Stein was one of those Christians who lived out of a hope transcending optimism and pessimism." Hers is a voice that speaks powerfully to all of us today, and a life that stands as testimony to the profoundest values of human existence, the significance of the individual, and the truths of faith that can reconcile Christian and Jew, philosophy and religion, oppressor and oppressed to heal a troubled world. New Saints and Blesseds of the Catholic Church, Vol. II (1984-1987)

New Saints and Blesseds of the Catholic Church, Vol. II (1984-1987)

by Ferdinand Holböck

320 pages. Paperback. $14.95

In this second volume of New Saints and Blesseds of the Catholic Church are depicted the lives and deaths, the struggles and battles of those women and men who were raised to the honors of the altar by Pope John Paul II during the fours years from 1984 through 1987, in forty-nine beatification ceremonies and in seven canonization liturgies.

Among them are Blesseds and Saints from a wide variety of countries, languages, ages and walks of life: lay people, religious, priests, and bishops, confessors and martyrs, including Edith Stein, Elizabeth of the Trinity, Titus Brandsma, Teresa of the Andes, and many more. All of them not only deserve reverence, but are worthy of imitation in their striving for perfection, in their fidelity to the Catholic faith and to the Church of Jesus Christ.

New: "The Second Vatican Council: The Four Constitutions"

Now available from Ignatius Press:

The Second Vatican Council: The Four Constitutions

The Second Vatican Council: The Four Constitutions

Introductory Essay by Pope Benedict XVI

This collection includes the four constitutions of the Second Vatican Council, the most popular and key documents for understanding the Council itself, its decrees, and its declarations.

Few events in the history of the modern Catholic Church have been as far-reaching as the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965). And few have been as controversial. No one denies great changes have come about since the close of the Council. Have the changes been all good, all bad, or a mixture of both? To what extent were the changes, for good or ill, the result of the Council itself?

Some have criticized the Council for not going far enough, though they maintain that the "spirit of Vatican II" supports their rejection of many firmly established Catholic beliefs and practices. Others claim the Council went too far and abandoned certain fundamental Catholic tenets in the name of "updating" the Church. The popes of the Council-John XXII and Paul VI-and their successors who also participated in the Council -John Paul I, John Paul II, and Benedict XVI-have insisted that the Council itself was the work of the Holy Spirit. They have aggressively criticized misinterpretations and distortions of it. They insist that the Council be understood in fundamental continuity with the Church's Tradition, even while deepening the Church's self-understanding and calling for authentic reforms and renewal of Catholic life.

Readers can learn for themselves what the Second Vatican Council taught using this highly accessible collection of its basic texts.

This book uses the Catholic Truth Society translation and features:

The Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium, introduced by Cardinal Francis Arinze.

The Dogmatic Constitution on the Church, Lumen Gentium, introduced by Cardinal Paul Poupard.

The Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation, Dei Verbum, introduced by Archbishop Charles J. Chaput, OFM, Cap.

The Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World, Gaudium et Spes, introduced by Cardinal Angelo Scola.

Four major aspects of the Church's life-the Sacred Liturgy, the mystery of the Church herself, the Word of God, and the Church in the world as it is today-are explored. No twenty-first-century Catholic should be without these four foundational texts in this superb translation.

The collection also includes a general introduction by Archbishop Salvatore Cordileone of San Francisco, as well as an address given by Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI in 2005, explaining how best to understand the Second Vatican Council in the history of the Church.

August 8, 2013

The Holy Inquisition: Dominic and the Dominicans

The Holy Inquisition: Dominic and the Dominicans | Guy Bedouelle, O.P. | From Saint Dominic: The Grace of the Word (Ignatius, 1987, 1995)

In his History of France, so characteristic of the nineteenth century, Jules Michelet has painted a fresco in which he shows the Church of the thirteenth century in Languedoc checking "the spirit of free thought" that represented heresy. The sentences pour out, nervous, breathless, romantic . . . and inexact. "This Dominic", he writes, "this terrifying founder of the Inquisition, was a Castilian noble. No one surpassed him in the gift of tears, a thing so often joined to fanaticism." [1] And in the following chapter he continues: "The Pope could only vanquish independent mysticism by himself opening great schools of mysticism: I refer to the mendicant orders. This was fighting evil with evil; attempting that most difficult of contradictions, the regulation of inspiration, the determination of illuminism . . . delirium unleashed!"

Pedro Berruguete's (d. 1504) tableau, the Scene of Auto da fé in the Prado museum in Madrid, is equally well known. St. Dominic, recognizable by his mantle ornamented with stars, is seated on a throne presiding over a tribunal and surrounded by six magistrates, almost all of them laymen. Below, to the right, are heretics roped to stakes soon to be set ablaze. The contrast is striking and the composition noteworthy. The tableau was doubtless intended for the glory of Dominic: the same painter designed several altar pieces for the Dominican convent in Avila at the request of Thomas of Torquemada (d. 1493), Inquisitor General in Spain in 1483.

If we go back a little further in history we shall find Dominican witnesses to show how Dominic took part in the first Inquisition against the Catharists and Vaudois in Languedoc. A reference made by Bernard Gui (1261-1331) in a Life of St. Dominic does not hesitate to claim for his Founder the title of First Inquisitor, following the "legendary" texts of the thirteenth century. [2] Nor has the author of the celebrated "Manual for Inquisitors" hesitated to interpolate on his own authority the Albigensian History of Pierre des Vaux de Cernai in order to prove Dominic's presence at the Battle of Muret during the bloody Albigensian Crusade on September 12, 1213: the Saint is pictured holding in his hands a crucifix riddled with wounds, which is still shown at St. Sernin in Toulouse. [3]

Lacordaire, on the contrary, at the moment when he was pleading before his "country" the cause of the reestablishment of the Order of Preachers in France in 1838, that is to say, a few years after the impassioned words of Michelet about the foundation of the mendicant orders, affirmed boldly (chap. 6) that "St. Dominic was not the inventor of the Inquisition, and never performed the duties of an inquisitor. The Dominicans were never the promoters or principal agents of the Inquisition." The historical demonstration following these claims must unfortunately be viewed with some reserve. It was - and not only on the basis of historical accuracy - vehemently attacked, in particular by his friend Dom Prosper Guéranger, the restorer of the Benedictines of Solesmes; he accused Lacordaire of not having the courage to "accept his heritage".

What, then, are we to believe? Was Dominic the first of the inquisitors? The answer is categorically: by no means! Simple chronology suffices to resolve the problem: Dominic died in 1221, and the office of Inquisitor was not established until 1231 in Lombardy and 1234 in Languedoc.

Were the Friars the principal agents of the Inquisition? Or did they simply take part in it "like everyone else", as Lacordaire says? This time the answer must be more nuanced. But we must know exactly what we are referring to when we use the word inquisition, so deadly in its ordinary connotation, before we can attempt to define its significance.

We must first realize that there were two inquisitions or, to put it better, two currents of inquisition, quite dissimilar in their origins and functions. The first, in the thirteenth century, was the result of a long process set in motion by the popes; it is often called "the pontifical inquisition". The second answered to an initiative of the Catholic kings of Spain who, in 1478, asked the pope to reorganize the former institution. This tool of royal absolutism - aimed at the religious minorities of Jews and Moslems, who were being assimilated with difficulty into the national life, and at the current trends of thought which seemed to be threatening the social order - would not be suppressed until the nineteenth century. This was the object of "the black legend", so tenacious that even today the term "inquisition" immediately arouses emotional reactions and evokes concepts of fanaticism and intolerance among the people. The kings of Spain often appealed to Dominicans like Thomas of Torquemada, but more often, from the end of the sixteenth century on, to Jesuits. [4]

When we speak of the Inquisition today we often confuse two entities which it would be greatly to our advantage to distinguish: a procedure and a tribunal. The Inquisitio is first of all a juridical procedure. It is the procedure of inquiry which, in modern nations, is officially opened by public authority when some crime is brought to its attention. It precedes the registering of a complaint or accusation, which in its turn will set in motion the handling of the civil offense. The introduction of this procedure is very objective and detailed: this is its guarantee for the accused. The method has come a long way in comparison with the ancient procedure of accusation, which was in early times very general in its character. This was the situation at the beginning of the thirteenth century in regard to heretics: they were prosecuted only after having been formally accused. Toward 1230 the process of inquiry was used in regard to matters of faith. The problem lay not in the process of inquiry itself, but in the fact that the royal and ecclesiastical authorities considered that a manifestation of dissent in matters of faith was a crime, subject to official prosecution.

The Inquisition was also a tribunal, an emergency tribunal destined to identify the crime for heresy, using among other procedures that of inquiry. This was the origin of the Office of Inquisition, entrusted to various persons. Without voiding the tribunal of the bishop which, up to that time, had dealt with matters of faith, this new tribunal largely substituted for it.

Heretofore, heresy had been handled as a spiritual matter by the bishop's tribunal, which was charged with assessing the belief of the baptized in a given diocese. The prince, who used secular constraint to obtain the accusation and punishment of those condemned for heresy, according to the normal functioning of his penal law, left to the bishop the final decision as to the validity of the accusation of heresy.

At the beginning of the thirteenth century Pope Innocent III's many moves against heretics, in sending legates to various parts of Christendom, served only to arouse and increase the bishops' action. There were vast campaigns of preaching, destined to bolster the belief of Catholics and to lead heretics back to the Faith. It was with one of these campaigns of the Word, being conducted in the Midi, that Dominic was associated (1206-1209).

The frequent inefficiency of the bishops' tribunals led Emperor Frederick II of Germany and Pope Gregory IX to move toward the creation of an emergency tribunal. Its judge would be a cleric, but the prince would vouch for its foundation and temporal effectiveness. He would determine the locales, maintenance, the carrying out of arrests, and appearances before the courts, as well as the penalties incurred according to his own penal laws. In 1231 a joint decision of Pope and Emperor led to the creation of the Office of the Inquisition, to be erected from that time on in Germany and Italy. This tribunal was introduced in northern France in 1233 and in the Midi at the beginning of 1234. It is clear, therefore, that it was not especially designed for the latter region as is commonly supposed. It had nothing to do with St. Dominic.

This office may be defined as an emergency tribunal set up on a permanent basis to deal with all matters involving the defense of the Faith, and using the inquisitorial procedure, which was far more flexible and effective. [5] It was not a "religious policy". It was a matter of convincing a heretic of the contradictory position he held in regard to the Christian Faith, and of converting him. The Inquisitor must therefore be a good preacher. For the least grave faults the tribunal imposed penalties of a religious nature: to carry a cross, to visit churches, to make pilgrimages - or more weighty undertakings. If the heretic was obdurate, the Church handed him over to the secular arm which could, from the thirteenth century on, decree the death penalty, forbidden however at the Third Lateran Council. From 1252 on, the Inquisition made use of the right to torture those charged with heresy, as was customary at the time in common law. We can see from this the importance of the role of the Inquisition.

The choice of the one who should be judge of the Faith was all the more serious in Pope Gregory IX's opinion, since he feared the danger of a judge too dependent on the prince, in whose service he could slight honesty in the performance of his duties. This was often the case with bishops, especially in Germany. The Pope therefore tended to choose religious, and sometimes secular priests. The first known Inquisitor, Conrad of Marburg, was a secular priest. Soon, however, the Pope turned to the Dominicans, particularly for France (1233) and Languedoc (1234). Two years later he added a Franciscan. In the ensuing years the Inquisitors of Languedoc were regularly Dominicans, those of Provence, Franciscans. These religious could devote themselves to instructing the people in the Faith with more continuity and greater depth than could monks or secular clergy, who were frequently drawn away to other tasks. But the Inquisition was never, as such, an office of the Order of Preachers.

The inquisitors were not responsible for the creation of the Inquisition. If some of them lost their sense of proportion due to the fearsome power given them, like the too celebrated Roger of Bougre, named in 1235, who dishonored his name by his excesses in northern France, most fulfilled the duties of judge entrusted to them with competence, freedom of spirit and a concern for the salvation of souls. They were convinced of the salutary need for this charge, as were most Christians in the West.

The problem of the Inquisition is rooted in two far older problems: that of the prosecution of heresy in Christian society and, more generally, that of the feelings of this society about disagreements within the body of the faithful.

The latter goes back to the origins of the Church, when Christians were intensely attached to "being of one mind" (Phil 2:2): "one Lord, one Faith, one baptism, one God and Father of us all" as St. Paul wrote (Eph 4:5). Faith was indeed entirely a gift of God; but to be authentic, it required belief and a common objective content.

It was Western society, ecclesiastical and political, which was responsible for creating and perfecting the Inquisition by a series of decisions on many levels. Western Christianity, welding the Church and temporal society together, believed it a just and holy thing to make Christian Faith and morals the basis for civil legislation and to place in its service the power of temporal coercion, of which the Inquisition was but one tool.

This sense of responsibility on the part of Europeans for the rule of Faith and for the salvation of their subjects, and their desire to intervene for its defense with the help of their bishops, remained very much alive in the West until the sixteenth century, even until the seventeenth. To rebel against the Faith was to rebel against the prince.

In their concern about salvation, so preponderant at the time, nations were often the first to insist on the prosecution of those who propagated teachings or methods of obtaining salvation that, in the judgment of the Church, risked the eternal loss of Christians. The man of the Middle Ages could understand tolerance of pagans who had no way of knowing revelation, but he was rigorous in dealing with Jews. This was to be the attitude of the papacy. It could regard deviations from the Catholic Faith and the repudiation of baptism only as grave sins. [6]

Dissension regarding the Faith thus appeared as the gravest of faults, by far the most pernicious. This is why the inquisitorial process sought first to cure, as a physician does. Not only the society that was threatened, but also the heretic himself, must be saved. This was the famous dilemma posed by Dostoyevsky in the striking scene of the Grand Inquisitor, depicted by him as an expression of Ivan Karamazov's revolt.

Throughout the Middle Ages this sort of temporal and spiritual collusion culminating in the Inquisition was considered normal. In none of the quarrels in which kings, emperors and rebellious clerics opposed the papacy - theologians like Marsile of Padua for example, so virulent and violent - do we find taunts about the Inquisition. Public opinion gave every evidence of approving, even desiring it. We must await the eve of the ideal of "tolerance", to find the challenging of at least the methods, if not the existence, of the institution. Erasmus, in this area as in others, seems to have been a precursor.

The Middle Ages were far more aware of social truths and values than of the sincerity of personal convictions. The deepening of the sense of the person and of liberty, though stressed by St. Paul as he considered Christian life to be ruled by grace (Gal 5:13) is a comparatively recent triumph. Our times cannot judge ages which thought otherwise. Our actual living out of this liberty is not, despite all the declarations of its intentions, favorable to the rights of man.

ENDNOTES:

[1] Vol. II, r. IV, chap. 7, Oeuvres complètes, vol. IV, critical edition, P. Viallaneix (Paris, 1974). In the first edition, Michelet wrote: "He was a noble Castilian, singularly charitable and pure. He was unsurpassed for his gift of tears and for the eloquence which drew tears from others." These last words were suppressed in 1852 and replaced by the vengeful sentence of 1861. "Examination of the revision of the text of 1833", op. cit., p. 657.

[2] For a statement of the question, see Vicaire, Dominique et ses Prêcheurs, pp. 36 57 ("Dominique et les Inquisiteurs", and also pp. 243 50).

[3] Cahiers de Fanjeaux, 16, pp. 243 5o (M. Prin and M. H. Vicaire).

[4] Guy Testas and Jean Testas, L'Inquisition (Paris, 1974).

[5] Cf "Le Credo, la morale et l'Inquisition", Cahiers de Fanjeaux 6 (1971), in particular the contributions of Yves Dossat. By the same author, Les crises de l'Inquisition toulousaine (1233 1273) (Bordeaux, 1959). See also Henri Maisonneuve, Etudes sur les origines de l'Inquisition, 2nd ed. (Paris, 1960); on Dominic and the early brethren, see pp. 248 49.

[6] For an exposition of the medieval attitude, see in the Summa Theologiae of St. Thomas, Ila IIae, q. 10. It is here that the famous formula is found: "The acceptance of faith is a matter of free will, yet keeping it when once it has been received is a matter of obligation" (10, a 10 ad 3).

Related Ignatius Insight Articles and Book Excerpts:

• St. Dominic and the Friars Preachers | Jordan Aumann, O.P.

• The Inquisitions of History: The Mythology and the Reality | Reverend Brian Van Hove, S.J.

• The Spanish Inquisition: Fact Versus Fiction | Marvin R. O'Connell

• The Crusades 101 | Jimmy Akin

• Were the Crusades Anti-Semitic? | Vince Ryan

• St. Thomas Aquinas and the Thirteenth Century | Josef Pieper

• Theologians and Saints | Hans Urs von Balthasar

• Catholic Spirituality | Thomas Howard

Guy Bedouelle, O.P. (b. 1940), is a French theologian, born in 1940 in Lisieux. He graduated from the Institut d'Etudes Politiques de Paris and has been the rector of the Catholic University of the West since 2008. He is the author of several books of Church history.

St. Dominic and the Friars Preachers

St. Dominic and the Friars Preachers | Jordan Aumann, O.P. | From Christian Spirituality in the Catholic Tradition | Ignatius Insight

Religious life continued to evolve in the thirteenth century as it had in the twelfth, and the evolution necessarily involved the retention of some traditional elements as well as the introduction of original creations. In fact, the variety of new forms of religious life reached such a point that the Lateran Council in 1215 and the Council of Lyons in 1274 prohibited the creation of new religious institutes henceforth.

Nevertheless, two new orders came into existence in the thirteenth century: the Franciscans and the Dominicans. As mendicant orders they both emphasized a strict observance of poverty; as apostolic orders, they were dedicated to the ministry of preaching. Yet there was a noticeable continuity between the newly founded mendicant orders and the older forms of monasticism and the life of the canons regular. At the risk of oversimplifying, we may say that the Franciscans adapted Benedictine monasticism to new needs while the Dominicans adapted the monastic observances of the Premonstratensians to the assiduous study of sacred truth, which characterized the Canons of St. Victor.

The mendicant orders, however, were not simply a development of monasticism; much more than that, they were a response to vital needs in the Church: the need to return to the Christian life of the Gospel (vita apostolica); the need to reform religious life, especially in the area of poverty; the need to extirpate the heresies of the time; the need to raise the level of the diocesan clergy; the need to preach the Gospel and administer the sacraments to the faithful. This was especially true of the Dominicans, who were consciously and explicitly designed to meet the needs of the times and to foster the "new" theology, Scholasticism. The Franciscans, as we shall see, were more in the tradition of the old monasticism and sought to return to a life of simplicity and poverty.

St Dominic Guzmán, born at Caleruega, Spain, in 1170 or 1171, was subprior of the Augustinian canons of the cathedral chapter at Osma. As a result of his travels with his bishop, Diego de Acevedo, he came face to face with the Albigensian heresy that was ravaging the Church in southern France. When they learned of the failure of the legates to make any progress in the conversion of the French heretics, Bishop Diego made a drastic recommendation. They should dismiss their retinue and, travelling on foot as mendicants, become itinerant preachers, as the apostles were.

In the autumn of 1206 Dominic founded the first cloister of Dominican nuns at Prouille; towards the end of 1207 Bishop Diego died at Osma, where he had returned to recruit more preachers. The work of preaching did not end with the death of Bishop Diego, but during the Albigensian Crusade under Simon Montfort, from 1209 to 1213, Dominic continued the work almost alone, with the approval of Pope Innocent III and the Council of Avignon (1209). By 1214 a group of associates had joined Dominic and in June, 1215, Bishop Fulk of Toulouse issued a document in which he declared: "We, Fulk, ... Institute Brother Dominic and his associates as preachers in our diocese . . . . They propose to travel on foot and to preach the word of the Gospel in evangelical poverty as religious." (56) The next step was to obtain the approval of the Holy See, and this was of special necessity in an age in which preaching was the prerogative of bishops. The opportunity presented itself when Dominic accompanied Bishop Fulk to Rome for the Lateran Council, which was convoked for November, 1215. According to Jordan of Saxony, Dominic desired confirmation on two points: the papal approval of an order dedicated to preaching and papal recognition of the revenues that had been granted to the community at Toulouse. (57)

Although Pope Innocent III was favorably inclined to the petition, he advised Dominic to return to Toulouse and consult with his companions regarding the adoption of a Rule. (58) Quite logically, the Rule chosen was that of St. Augustine, as Hinnebusch points out:

The adoption was dictated by the specific purpose St. Dominic sought to achieve -- the salvation of souls through preaching -- an eminently clerical function. The Rule of St. Augustine was best suited for this purpose. During the preceding century it had becomepar excellence the Rule of canons, clerical religious. In its emphasis on personal poverty and fraternal charity, in its reference to the common life lived by the Christians of the apostolic age, in its author, it was an apostolic Rule. Its prescriptions were general enough to allow great flexibility; it would not stand in the way of particular constitutions designed to achieve the special end of the Order. (59)

In addition to the Rule of St. Augustine, the early Dominicans used the customs of the Premonstratensians as a source for their monastic observances, for which reason they were often called canons as well as mendicant friars. What was peculiar to the Dominican Order was added by the first Chapter of 1216 and the General Chapter Of 1220: the salvation of souls through preaching as the primary end of the Order; the assiduous study of sacred truth to replace the monastic lectio divina and manual labor; great insistence on silence as an aid to study; brisk and succinct recitation of the choral office lest the study of sacred truth be impeded; the use of dispensations for reasons of study and the apostolate as well as illness; election of superiors by the community or province,; annual General Chapter of the entire Order; profession of obedience to the Master General; and strict personal and community poverty.

On December 22, 1216, the Order of Friars Preachers was confirmed by the papal bull, Religiosam vitam, signed by Pope Honorius III and eighteen cardinals. On January 21, 1217, the pope issued a second bull, Gratiarum omnium, in which he addressed Dominic and his companions as Friars Preachers and entrusted them with the mission of preaching. He called them "Christ's unconquered athletes, armed with the shield of faith and the helmet of salvation" and took them under his protection as his "special sons." (60)

From that time until his death in 1221, St. Dominic received numerous bulls from the Holy See, of which more than thirty have survived. The same theme is found in all of them: the Order of Preachers is approved and recommended by the Church for the ministry of preaching. St. Dominic himself left very little in writing, although we may presume that he carried on an extensive correspondence. The writings attributed to him are theBook of Customs, based on the Institutiones of the Premonstratensians; the Constitutions for the cloistered Dominican nuns of San Sisto in Rome; and a personal letter to the Dominican nuns at Madrid.

The Dominican friars were fully aware of the mission entrusted to them by Pope Honorius III. In the prologue of the primitive Constitutions we read that "the prelate shall have power to dispense the brethren in his priory when it shall seem expedient to him, especially in those things that are seen to impede study, preaching, or the good of souls, since it is known that our Order was especially founded from the beginning for preaching and the salvation of souls." (61)

"This text," says Hinnebusch, "is the keystone of the apostolic Order of Friars Preachers. The ultimate end of the Order, it states, is the salvation of souls; the specific end,. preaching; the indispensable means, study. The power of dispensation will facilitate the attainment of these high purposes. All this is new, almost radical." (62) On the other hand, it may be interpreted as a return to the authentic "vita apostolica," and that is the way St. Thomas Aquinas would see it: "The apostolic life consists in this, that having abandoned everything, they should go throughout the world announcing and preaching the Gospel, as is made clear in Matthew 10:7-10." (63)

Preachers of the Gospel need to be fortified by sound doctrine, and for that reason the first General Chapter of the Order specified that in every priory there should be a professor. Quite logically, the assiduous study of sacred truth, which replaced the manual labor and lectio divina of monasticism, would in time produce outstanding theologians and would also extend the concept of Dominican preaching to include teaching and writing.

Dominican life was also contemplative, not in the monastic tradition, but in the canonical manner of the Victorines; that is to say, its contemplative aspect was manifested especially in the assiduous study of sacred truth and in the liturgical worship of God. However, even the contemplative occupation of study was directly ordered to the salvation of souls through preaching and teaching, and the liturgy, in turn, was streamlined with a view to the study that prepared the friars for their apostolate. Thus, the primitive Constitutions stated:

Our study Ought to tend principally, ardently, and with the highest endeavor to the end that we might be useful to the souls of our neighbors. (64)

All the hours are to be said in church briefly and succinctly lest the brethren lose devotion and their study be in any way impeded. (65)

Because of the central role which the study of sacred truth plays in the Dominican life, the spirituality of the Friars Preachers is at once a doctrinal spirituality and an apostolic spirituality. (66) By the same token, the greatest contribution which the Dominicans have made to the Church through the centuries has been in the area of sacred doctrine, whether from the pulpit of the preacher, the platform of the teacher or the books of the writer. The assiduous study of sacred truth, so strictly enjoined on the friars by St. Dominic, provides the contemplative attitude from which the Friar Preacher gives to others the fruits of his contemplation. In this restricted sense we may say with Walgrave that the Dominican is a "contemplative apostle." (67)

ENDNOTES:

(56) Cf. Laurent, Monumenta historica S. Dominici, Paris, 1933, Vol. 15, p. 60.

(57) Jordan of Saxony, Libellus de principiis ordinis praedicatorum, ed. H. C. Scheeben in Monumenta O. P. Historica, Rome, 1935, pp. 1-88.

(58) The Fourth Lateran Council forbade the foundation of new religious institutes unless they were extensions of an existing institute or adopted an approved Rule.

(59) W. Hinnebusch, The History of the Dominican Order, New York, N.Y., 1965, Vol. 1, p. 44. The Rule of St. Augustine was also adopted by numerous other religious institutes founded in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.

(60) Cf. W. Hinnebusch, op.cit., p. 49. On February 17, 1217, a third papal bull, Jus petentium, specified that a Dominican friar could not transfer to any but a stricter religious institute and approved the stability pledged to the Dominican Order rather than to a particular church or monastery.

(61) I Constitutiones S.O.P., prologue; cf. P. Mandonnet-M. H. Vicaire, S. Dominique: l'idee, l'homme et l'oeuvre, 2 vols., Paris, 1938.

(62) Cf. W. Hinnebusch, op. cit., p. 84.

(63) Contra impugnantes Dei cultum et religionem.

(64) I Const. S.O.P., prologue; cf. W. Hinnebusch, op. cit., p. 84.

(65) I Const. S.O.P., n. 4; cf. W. Hinnebusch, op. cit., p. 351.

(66) Cf. M. S. Gillet, Encyclical Letter on Dominican Spirituality, Santa Sabina, Rome, 1945 Mandonnet-Vicaire, op. cit.; V. Walgrave, Dominican Self-Appraisal in the Light of the Council, Priory Press, Chicago, Ill., 1968; S. Tugwell, The Way of the Preacher, Templegate, Springfield, Ill., 1979; H. Clérissac, The Spirit of St. Dominic, London, 1939.

(67) V. Walgrave, op. cit., pp. 39-42.

Related Ignatius Insight Articles and Book Excerpts:

• St. Thomas Aquinas and the Thirteenth Century | Josef Pieper

• Theologians and Saints | Hans Urs von Balthasar

• Catholic Spirituality | Thomas Howard

Jordan Aumann, O.P. (1916-2007), was a theologian and spiritual writer who authored Christian Spirituality in the Catholic Tradition and Spiritual Theology.

Jim Gaffigan on Fatherhood for the Recovering Narcissist

Jim Gaffigan on Fatherhood for the Recovering Narcissist | Thomas P. Harmon | CWR

The comedian’s new book Dad is Fat has a delightfully subversive message on fatherhood and the family.

Jim Gaffigan

is Catholic. As he wryly informs us, his wife is “Shiite Catholic.” Does that

make his new book, Dad

Is Fat, Catholic? Is he, as the Washington

Post’s Michelle Boorstein put it, “the

Catholic Church’s newest evangelizer”? Boorstein seems to want to say yes, although Gaffigan’s style is more

subtle than most people would associate with the word “evangelism.” After all,

you won’t hear “Christ, and him crucified” in so many words from Gaffigan.

Sometimes, however, evangelism can have a very different meaning. In

modern America, most people have a certain view of devout Catholics—they’re

either recent immigrants who will assimilate away from the Church, or they’re repressed

weirdos with strange ideas about sex who probably hate all sorts of people

(women, gays, Muslims, etc.). In any case, they can’t possibly be happy and

well-adjusted.

And yet, there’s Gaffigan. He’s open about being Catholic, although he’s

no Catechism-thumper (not that

there’s anything wrong with that!). He has what many people—especially his

neighbors in the Bowery in Manhattan—would consider an unimaginably large

family (five kids!) and, while he seems tired, he also clearly thinks the kids

are worth it. He has a lovely wife who is very attentive to the kids, but apparently

neither he nor she thinks marriage and family detract from the enjoyment of

life. In fact, he seems pretty happy and not nearly as neurotic as most of the

other comics you’ll see doing specials on Comedy Central. In fact, despite his

acquisition of fame, he seems pretty normal. The thought may even begin to

creep in: maybe he’s happy because of

all the weird stuff that look like trappings of his kooky religion. And once that thought’s present, it’s not too

far away from the thought: maybe it’s not so kooky after all.

That being said, most of Gaffigan’s comedy is not about the Catholic

faith. As a matter of fact, he never seems terribly interested in making

Catholicism a subject of his comedy, except for the occasional joke about how

long Mass is or that Catholics have guilt. That’s why his stand-up and his new

book, Dad is Fat, are so deliciously

subversive.

Continue reading at www.CatholicWorldReport.com.

August 7, 2013

St. Joseph, “blessed spouse of Mary”

by Fr. David Vincent Meconi, SJ | HPR Editorial | August 2013

Scripture and sacred tradition do not tell us too much about Joseph. Yet, all we need to know is that the heart of his life beats between Mary and Jesus, how he found his truest self between our Lady and her God.

August is a month of transitions. It is when we honor our Lady’s Glorious Assumption and her Coronation as Queen of heaven and earth. It is also the month most families begin to worry about school supplies, new schedules, and the stresses of having summer come to a close. August also witnesses the vows of many men and women religious as well as the entrance of new novices into their communities. It is when our diocesan seminarians report for duty. And this just in: August has recently outpaced June as the top month for weddings. It is truly a time of change and hopeful expectation.

To contemplate our Lady’s role in heaven this month is to recall how she intercedes for all of us in all of these various circumstances here on earth. As we all pray for our new classes of religious and seminarians, for schoolchildren’s safety all around the world, and for all this month brings, I am grateful that St. Joseph now has a more a visible—at least, a more audible—part of our daily worship. For behind Mary’s tender care of Christ stood Joseph, that “just man” extolled in the scriptures. Joseph was no doubt the first one to whom Mary revealed her Immaculate Heart, trusting his strong silence as a place where her most intimate secrets and hopes for this new mystery inside of her would be safe.

On June 20 of this year, the Vatican’s Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments declared that the name of St. Joseph “blessed spouse” of Mary, was to be added to the canon of the Mass, added to Eucharistic Prayers II, III, and IV of the Roman Missal. (One wonders why Rome could not have made this decision last year when the new {and expensive} Missals were being printed, as this was a change already being talked about at the beginning of Emeritus Benedict’s pontificate.) As a universal and mandatory change, we should now hear at every Mass:

The Rebirth of the Irish Pro-Life Movement

The Rebirth of the Irish Pro-Life Movement | Michael Kelly | CWR

The legalization of abortion in Ireland has mobilized pro-life activism.

Within weeks, hospitals in Ireland could, for the first time, begin performing abortions. It comes after Irish President Michael D. Higgins signed a controversial piece of legislation that the government insists allows for abortion only in limited circumstances, but that pro-lifers argue permits an extremely liberal abortion regime.

A brief statement from Higgins July 27 confirmed that the president had signed the so-called Protection of Life in Pregnancy Bill. Ironically, his endorsement of the law may well prove to be a blessing for pro-life advocates. Under the 1937 Irish Constitution, the president is vested with very little power and is virtually obliged to sign laws that have passed parliament. However, in a little-used constitutional provision, the president does have the power to refer laws to the Supreme Court to test their constitutionality before signing. Had Higgins opted to refer the law to the Court, this would’ve delayed the passage of the bill. However, if the Supreme Court ruled that the law was in keeping with the Constitution, the bill would be forever immune to challenge. President Higgins’ decision to sign without reference to the Supreme Court clears the way for those opposed to abortion to challenge the law.

Prime Minister Enda Kenny, whose claim that he supports abortion in some circumstances because he is pro-life have led some pro-lifers to accuse him of verbal acrobatics, has not survived the passage of the law unscathed. A number of his government legislators were expelled from his center-right Fine Gael party for refusing to support abortion, which may weaken Kenny’s overall position at the head of the country’s coalition government.

Veteran pro-life campaigners describe the passage of the law as a dark day for Ireland. But, in a country where a ban on abortion was sometimes taken for granted, the campaign may also have emboldened and united opponents of abortion as never before.

Going forth into the “night” of our culture

Going forth into the “night” of our culture | Thomas M. Doran | CWR blog

Catholics need to engage the culture through the secular media. Here's why and how.

Pope Francis recently addressed to the Brazilian bishops, saying, “The two disciples have left Jerusalem. They are leaving behind the 'nakedness' of God. They are scandalized by the failure of the Messiah in whom they had hoped and who now appeared utterly vanquished, humiliated, even after the third day. Here we have to face the difficult mystery of those people who leave the Church, who, under the illusion of alternative ideas, now think that the Church – their Jerusalem – can no longer offer them anything meaningful and important. So they set off on the road alone, with their disappointment. Perhaps the Church appeared too weak, perhaps too distant from their needs, perhaps too poor to respond to their concerns, perhaps too cold, perhaps too caught up with itself, perhaps a prisoner of its own rigid formulas, perhaps the world seems to have made the Church a relic of the past, unfit for new questions; perhaps the Church could speak to people in their infancy but not to those come of age. It is a fact that nowadays there are many people like the two disciples of Emmaus; not only those looking for answers in the new religious groups that are sprouting up, but also those who already seem godless, both in theory and in practice.

"Faced with this situation, what are we to do?

"We need a Church unafraid of going forth into their night. We need a Church capable of meeting them on their way. We need a Church capable of entering into their conversation. We need a Church able to dialogue with those disciples who, having left Jerusalem behind, are wandering aimlessly, alone, with their own disappointment, disillusioned by a Christianity now considered barren, fruitless soil, incapable of generating meaning.”

This is what we, not just bishops and priests, are called to do by Christ and by his Church.

One of the arenas where this “night” is darkest is the secular media. Many Catholics, discouraged or scandalized by what they see in the media, choose to ignore it, as Tolkien’s hobbits ignored the shadow in the south. Believers often retract into the shells of their parish communities, or family, friends, and media they trust. Unfortunately, without engaging and influencing the culture – changing minds and hearts – these “Shires” may also be overrun.

For those Catholics who, by training or aptitude, are capable of engaging the culture through the secular media, avoidance is not the answer. In a word, you may be the only authentic voice of truth that a lapsed Catholic, agnostic, or materialist hears.

How can this engagement be accomplished, considering a media culture that is increasingly ignorant of the Church, and often hostile toward her?

August 6, 2013

"The Transfiguration: Gospel to the Dead" by Frank Sheed

From To Know Christ Jesus

At Caesarea Philippi Jesus told the apostles that he would suffer and die and on the third day rise again. A week later, transfigured upon a mountain, he told Moses and Elijah.

Present when he told them were Peter and James and John, whom he had chosen to have with him when he raised Jairus' dead daughter to life, and whom he would choose to have nearest to him in Gethsemane. We tend to think of them as principals at the Transfiguration, almost as though the whole incident had been staged for their sake. Strengthened and comforted by it they certainly were; but they were not principals. Jesus conversed with Moses and Elijah: the three apostles were asleep part of the time and contributed nothing. Only one of them said anything at all: Peter said that it was a good thing they were there—they could make three shelters, one for Jesus, one for Moses, one for Elijah; but he himself tells us, through Mark (9:5), that he was too frightened to know what he was saying.

Let us glance quickly at what happened as told in the opening verses of Mark's ninth chapter and Matthew's seventeenth. Read especially Luke (9:28-36). He gives the most detailed account, and we wonder who was his informant. Of the three who were there, Peter tells us what happened through Mark (and find it again in 2 Peter 1:17-18—be sure to read it); James was long dead; could it have been John? Apart from "we saw his glory, he glory as of the only begotten of the Father", he says nothing of the Transfiguration in his own Gospel. It may be that Luke had a ready told all that John had to tell.

As at Caesarea Philippi, Jesus had climbed some way up a mountain to pray. As he prayed he was "transfigured"—the Greek word is "metamorphosed"—his face shining like the sun, his garments dazzling white, like snow. It is not clear at what point the three apostles went to sleep, but when they were fully awake they saw their Lord "in his glory", and Moses and Elijah standing with him, they too in glory. The three were speaking of the death that he would die in Jerusalem.

Moses was Israel's law giver, dead these fifteen hundred years. Elijah, greatest of prophets, had been whirled up into the sky eight hundred years before; and the prophet Malachi had said (4:5) that God would send him "before the coming of the great and awe-filled day of the Lord". Where had they come from?

Of Elijah the destiny is wholly mysterious. About Moses there is no such mystery. He was simply one of the greatest of those who had died at peace with God. Heaven was closed to these until Calvary should expiate the sin of the race. The soul of Moses, and the souls of all of them, were in a place of waiting—limbo, the border region, we most often call it. Abraham's bosom, Jesus called it in the parable of Dives and Lazarus; paradise, he called it to the thief who appealed to him on the Cross.

Supremely Moses represented the Law, and Elijah the prophets. What happened on the mountain established the continuity between Israel of old and the Kingdom, now at last to be founded, in which Israel was to find its fulfillment. It seems strange that the representatives of the Kingdom were, as they would be likewise in Gethsemane, asleep part of the time, and frightened when they were fully awake. It was no very stimulating account Moses would take back to limbo of the men on whom the Kingdom was to be built.

But for these—long dead or newly dead—who had been waiting in all patience till the Redeemer should open heaven to them, Peter, James, and John must have mattered little compared with the news Moses brought back that their redemption was at hand and how it was to be accomplished. What Jesus had told at Caesarea Philippi to men living upon earth, he now told through Moses to the expectant dead. Through Moses the Law had been given to the children of Israel. Through Moses the Gospel, the good news, reached limbo.

As Peter finished his proposal to build three shelters, a luminous cloud overshadowed them, wrapping them round so that once again they were afraid. A Voice came out of the cloud saying: "This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased: hear ye him." The last three words, establishing our Lord's authority as teacher, were new. All the rest had been said by the same Voice at Jesus' baptism in Jordan.

Peter, James, and John had been afraid—afraid when they saw Jesus and Moses and Elijah all white and luminous, afraid when the cloud wrapped them round, afraid when the Voice sounded from the cloud. With a touch of his hand and the words "Arise and fear not", he recalled them to the world they were used to.

As they raised their frightened faces, they saw "no one but only Jesus"! He told them to say nothing of what they had seen on the mountain till the Son of Man (still his own phrase for himself, used of him by none of them) should be risen from the dead. Among themselves, they wondered just what that "risen from the dead" might mean. They had seen the daughter of Jairus and the young man of Nain dead and alive again. But they could not imagine how all this could apply to him who had raised those two.

And there was another problem, which they did discuss with Jesus himself as he and they came down the slope next day. They had just seen Elijah, and with this talk of Jesus dying, they would remember that Elijah had not died like other men; and they would remember that Malachi had said that Elijah would return and restore a sinful people to virtue before the day of the Lord. It was all very puzzling, and they put the puzzle to their Master. His answer, to the effect that Elijah had already returned in the person of John the Baptist, might have been clearer to them, had they known what the angel had said to Zechariah in the annunciation of John's birth (Lk 1:17)—"He shall go before the Lord in the spirit and power of Elijah ... to prepare unto the Lord a perfect people." At least they would have remembered that Elijah had lived in the desert, preached repentance, and rebuked rulers.

Related Ignatius Insight Book Excerpts:

• St. John the Baptist, Forerunner | Frank Sheed

• The Incarnation | Frank Sheed

• The Problem of Life's Purpose | Frank Sheed

Frank Sheed (1897-1981) was an Australian of Irish descent. A law student, he graduated from Sydney University in Arts and Law, then moved in 1926, with his wife Maisie Ward, to London. There they founded the well-known Catholic publishing house of Sheed & Ward in 1926, which published some of the finest Catholic literature of the first half of the twentieth century.

Frank Sheed (1897-1981) was an Australian of Irish descent. A law student, he graduated from Sydney University in Arts and Law, then moved in 1926, with his wife Maisie Ward, to London. There they founded the well-known Catholic publishing house of Sheed & Ward in 1926, which published some of the finest Catholic literature of the first half of the twentieth century.

Known for his sharp mind and clarity of expression, Sheed became one of the most famous Catholic apologists of the century. He was an outstanding street-corner speaker who popularized the Catholic Evidence Guild in both England and America (where he later resided). In 1957 he received a doctorate of Sacred Theology honoris causa authorized by the Sacred Congregation of Seminaries and Universities in Rome.

Although he was a cradle Catholic, Sheed was a central figure in what he called the "Catholic Intellectual Revival," an influential and loosely knit group of converts to the Catholic Faith, including authors such as G.K. Chesterton, Evelyn Waugh, Arnold Lunn, and Ronald Knox.

Sheed wrote several books, the best known being Theology and Sanity, A Map of Life, Theology for Beginners and To Know Christ Jesus. He and Maise also compiled the Catholic Evidence Training Outlines, which included his notes for training outdoor speakers and apologists and is still a valuable tool for Catholic apologists and catechists (and is available through the Catholic Evidence Guild).

For more about Sheed, visit his IgnatiusInsight.com Author Page.

Blessed Grapes and Hymns of Glory: The Feast of the Transfiguration in the Eastern Churches

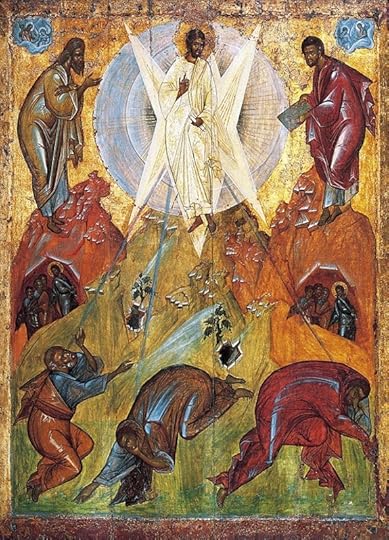

Transfiguration icon by Theophanes the Greek (15th c.).

Blessed Grapes and Hymns of Glory: The Feast of the Transfiguration in the Eastern Churches | Christopher B. Warner

Contemplation of Christological events, like the Transfiguration, has propagated a magnificent wealth of liturgical poetry and hymnography in the Eastern Church

August 6th commemorates Christ’s transfiguration in glory on Mount Tabor. The Transfiguration is one of twelve major feasts on the Eastern Christian liturgical calendar. A major feast is the equivalent of a solemnity on the Roman calendar. A glimpse of this feast through the hymns and traditions of the East gives a fresh perspective on God’s plan of salvation for us.

“My favorite part of this feast is singing the troparion,” says Robin Roxas of Morning Star Family Farm in Hartland, Wisconsin. Robin and his family of ten traveled an hour from their farm yesterday evening in order to celebrate the Vesperal Divine Liturgy of the Feast at their Greek Catholic parish in Milwaukee. Roxas commented on the tradition his family has of singing the troparion during family prayers at home. “My children love to sing this hymn,” Roxas told CWR. This feast is a special one for Eastern Christian farmers around the world because it is customary to bring the first fruits of the summer harvest to be blessed by the priest during the Divine Liturgy.

Each feast of the Lord serves to illuminate the rich gestalt of the Incarnate Mystery. The Eastern Christian hymnography for the feast of the Transfiguration of Our Lord on Mount Tabor, like all major festal hymnography, is full of references to the life, death, and Resurrection of Christ. Hymn references like this stichera, composed by Cosmas the monk, sung at Great Vespers is an example:

Before Your Crucifixion, O Lord, taking the disciples up onto a high mountain, You were transfigured before them… from love of mankind and in Your sovereign might, Your desire was to show them the splendor of the Resurrection. Grant that we too, in peace, may be counted worthy of this splendor, O God, for You are merciful and the lover of mankind.

Without the Transfiguration and the other events of Jesus’ life, it would be difficult to grasp the totality of the paschal mystery and its implication for our lives. The raising of Lazarus from the dead, for example, gives Christians hope that they will one day participate in Christ’s Resurrection. Contemplation of these Christological events has propagated a magnificent wealth of liturgical poetry and hymnography – a major source of theology for Eastern Christians.

Eastern Christians speak about the divine "economy". This economy has nothing to do with money and everything to do with God’s plan of salvation which culminates in Christ. The following sessional hymn from Matins of the Transfiguration illustrates the purpose God had for the chief Apostles of the Lord and, by extension, all his co-heirs: that they be filled with life, love, and goodness:

As they gazed upon Your glory, O Master, they were struck with wonder at Your blinding brightness. You who have shone upon them with Your light, give light now to our souls… confirm me in Your love: for You are our supreme desire and the support of the faithful, O You who alone are the lover of mankind. (Irmos)

The Holy Feast of the Transfiguration of Our Lord is about divine encounter: “And he was transfigured before them, and his garments became glistening, intensely white” (Mk 9:2).” In Eastern iconography, Jesus is depicted against an oval shaped backdrop with rays emanating out of it called a "mandorla", which represents the radiance of his uncreated Glory. During the matins service, the following words demonstrate that the glory which radiates from Christ is not a product of human nature but comes from God alone:

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers