Carl E. Olson's Blog, page 144

July 4, 2013

No Faith, No Freedom. Know Faith, Know Freedom.

The state of Maryland was the first experiment in religious

freedom in human history. Lord Baltimore and his Catholics were a long

march ahead of William Penn and his Quakers on what is now called the

path of progress. That the first religious toleration ever granted in

the world was granted by Roman Catholics is one of those little

informing details with which our Victorian histories did not exactly

teem." — G. K. Chesterton, What I Saw in America

"Where

society is so organized as to reduce arbitrarily or even suppress the

sphere in which freedom is legitimately exercised, the result is that

the life of society becomes progressively disorganized and goes into

decline." — Bl. John Paul II, Centesimus Annus, 25.

"But

freedom attains its full development only by accepting the truth. In a

world without truth, freedom loses its foundation and man is exposed to

the violence of passion and to manipulation, both open and hidden." —

Bl. John Paul II, Centesimus Annus, 46.

Today is

Independence Day in the United States, a day marked by celebrations

large and loud, festive and familial. The word of the day, the defining

characteristic of the celebration of the signing and adoption of the

Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, is "freedom". Today also

marks the conclusion of the second "Fortnight of Freedom", which

commenced on June 21st, the vigil of the Feast of St. John Fisher and

St. Thomas More. It should give pause, if for only a moment, that the

"Fortnight" began on the feast day of two English martyrs and then ends

on the National Day commemorating the 237th anniversary of a declaration

of independence from the rule of Great Britain. Among other things, it

speaks to the fact that while religious freedom has a special place in

the history of the United States—see the quote above from

Chesterton—that freedom is catholic, something that all men and women

should enjoy, even though so many throughout the world do not. It also

speaks to the special relationship between Catholicism and freedom, a

relationship little understood and rarely acknowledged in a country

whose historical and cultural foundation was largely Protestant in

nature.

And what of today? In thinking of today, specifically

and in the broader sense of the current age, it is notable that Pope

Francis will tomorrow release his first encyclical, Lumen Fidei

("The Light of Faith"), which is reported to be the joint work of

Francis and Benedict XVI. Rather than coincidental, the timing is

fortuitous. That fact hit home when, in the process of cleaning my

office yesterday, I re-discovered a book about the relationship between

freedom and faith, written by an English scholar (my office usually has

several stacks of books, each with 20 or 30 books, so such "discoveries"

are hardly unusual). Several passages caught my attention, but I'll

share just a couple of them. Bypassing the context for a moment, here's

the first passage:

The

confidence in state action, the glorification of technology, the

unlimited faith in science, the centralization of decision, and the

subordination of low to so-called mass interests—all these … have helped

in the West to create communities in which the individual citizens

feels overwhelmed, isolated, and helpless before the anonymities of

public and private bureaucracy. We are right to fear these vast

distortions of tendencies already at work in our society.

It is a

fine summation of the broad (and deep) problems faced today, yet it is

not original. Except that it was written, not in the past few years, but

over sixty years ago, in the the early 1950s. The book is Faith and Freedom,

the author was Barbara Ward, and the publisher was Image; the subhead

is: "A stimulating inquiry into the history and relationship of

political freedom and religious faith." It is a book worth tracking down

for many reasons, among them Ward's beautiful and learned writing, the

historical perspective presented, and the philosophical insights, which

are just as meaningful today, if not more so, than there were when the

book was first published in England in 1954.

Ward has some

interesting things to say about the War for Independence and the

founding of the United States, but I am more interested here in her

thoughts on dealing with and fighting against tyranny.

Democracy, the Death of Truth, and the Growth of Tyranny

Democracy, the Death of Truth, and the Growth of Tyranny | Brian Jones | CWR

Choosing to live according to one’s own self-made conception of reality, human nature, and happiness is a recipe for tyranny.

My wife

recently had a discussion with a former high school friend of hers

regarding the Gosnell abortion trial in Philadelphia. They were in

complete agreement that what this so-called “doctor” had done was

intentionally taking the lives of innocent children, discarding these

little souls as though they were mere things, capable of being

disposed at will. However, it was also clear that my wife's friend,

admitting the truth of these horrors, was hesitant, perhaps even

unwilling, to carry the premises to their logical conclusion. His

final remark was this brief summation of his philosophical worldview:

I agree with you

that this case (Gosnell) is quite disturbing on so many levels. I

would never want my wife to have an abortion, nor would I ever

conceive of counseling a woman that abortion would be a wise choice.

However, I must declare my agnosticism on this issue, for I

personally do not know when human life begins and I am not certain

that the science is definitive on this point either. Furthermore,

while I may disagree with the person’s decision, nevertheless, who

am I to deny someone the sacred right of choice to determine what is

best for them in their lives, and in the complicated circumstances

that envelope their situation?

While much can be said, and has been

said, about the claims put forth in such a statement, what should

stand out most is that this is the philosophical outlook of modern

liberal democracy, its penultimate truism on which it is based and

feeds. Relativism and toleration are its paradigmatic doctrines, for

if one proposed some form of truth and and also proposed that we

could simultaneously know this truth that we ourselves did not make,

then one would be a threat to civilization. It is only on the

conditions of dialogue, equality, and the affirmation of any and all

forms of living that we can remain a free and open society, one

progressing towards a better world.

Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger himself

diagnosed this dangerous current of philosophical relativism in

modern democratic societies. Democracy, Ratzginer noted, is in fact

built upon the basis,

that no one can

presume to know the true way, and it is enriched by the fact that all

roads are mutually recognized as fragments of the effort toward that

which is better... A system of freedom ought to be essentially a

system of positions that are connected with one another because they

are relative as well as being dependent on historical situations open

to new developments. Therefore a liberal society would be a

relativist society: only with that condition could it continue to be

free and open to the future. (“Address to Latin American Bishops”,

1996).

Ratzinger rightly highlights in this

same address that there must be a certain amount of relativism in the

arena of politics for, as Aristotle tells us, this science is not

speculative, but practical.

July 3, 2013

Two Cheers for Democracy

Two Cheers for Democracy | Benjamin Wiker | CWR

Patriotic, modest, and tempered praise for our present form of government

Happy

237th birthday, America! Two cheers for democracy!

Why

only two? Aren’t we supposed to cheer wildly for democracy as unambiguously

good? Don’t we have a moral obligation to hold up democracy as the best—indeed,

the only legitimate—form of government? Isn’t it the only form of government

that expresses the fundamental moral and theological truth that all human

beings are equal, have equal dignity, are equally children of God, have equal

rights, and all of the other equal things anyone can think of?

Well,

certainly if I were running for political office, I would have to cheer for

democracy with unbridled exuberance. I would have to say something like, “Three

cheers for democracy?!—no, make that a hundred!”

And if

the other candidate suggested that two cheers might be more modestly

appropriate, then I’d win hands down. “Two cheers, you say? This man is a totalitarian,

a bigot, an enemy of the common man. I think we see who is for the people, and who is against.”

Then

I’d be cheered wildly, and get elected in a landslide.

But

I’m not running for office, so it’s a lot easier to speak the truth.

If we

recognize the humor in that last comment (even if only as sarcasm, the lowest

end of the humor spectrum), then we realize, in part, why we might consider

giving only two cheers for democracy.

We

realize that, all too often, trying to get elected means bending one’s message

to the popular ear, trying to make oneself salable, making use of the exact

same techniques as ad agencies use to sell Coke and deodorant, manipulating the

masses through slick ads, mud-slinging ads, mawkishly patriotic ads,

disingenuous ads.

Getting

elected means telling people what they want to hear, rather than telling them

the truth about the actual political situation. So that those who flatter and

fawn, who look the best, speak the best, are able to rouse the most passion,

are the ones who get elected—rather than those who might actually be able to do

the best job.

What

if the actual best person to be our president were a short, shy, dumpy, bald

guy with a biggish nose and crooked teeth, who spoke with a squeaky stutter?

Would he get elected?

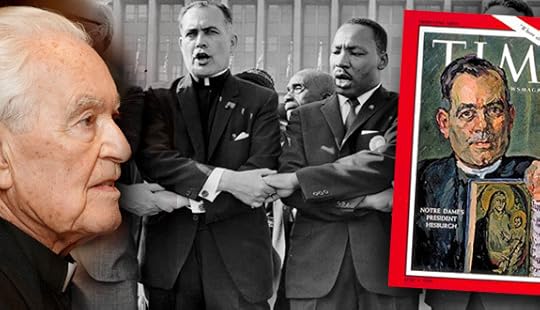

The Problematic Legacy of Fr. Hesburgh

The Problematic Legacy of Fr. Hesburgh | Anne Hendershott | CWR

A beloved leader in Catholic higher education, he also accelerated the move toward secularization of Catholic institutions.

Standing in front of a famous

1964 photo of Father Theodore Hesburgh locking arms with the Rev. Martin Luther

King, Nancy Pelosi, the House minority leader, honored Father Hesburgh at a

party on Capitol Hill celebrating the retired president of the University of

Notre Dame’s 96th birthday in late May.

During her celebratory remarks, Pelosi praised Father Hesburgh’s

courageous record on civil rights and pointed to the photo, on loan from the

National Portrait Gallery, taken at a rally just days after a vote on the Civil

Rights Act. Pelosi was joined at the party

by dozens of congressional well-wishers—as well as Vice President Joe Biden—all

paying tribute to the priest that Biden described as “the most powerful

unelected official this nation has ever seen.”

Biden is correct. Father Hesburgh has indeed exerted a powerful

influence on our country, on our Church, and especially on our Catholic

colleges and universities. He has

received 150 honorary degrees, the most ever awarded to one person, and has

held 16 presidential appointments involving most of the major social issues in

his time—including civil rights, nuclear disarmament, population, the

environment, Third World development, and amnesty and immigration reform. In

July 2000, President Clinton awarded Father Hesburgh the Congressional Gold Medal—making him the first person

from higher education to be so honored.

Father Hesburgh has always viewed

himself as a “citizen of the world” and his secular activities reflect

that. Father Hesburgh was the first priest ever elected

to the Board of Directors at Harvard University and served two years as

president of the Harvard Board. He also

served as a director of the Chase Manhattan Bank. A longtime champion of

nuclear disarmament, Father Hesburgh has served on the board

of the United States Institute of Peace and helped organize a meeting of

scientists and representative leaders of six faith traditions who called for

the elimination of nuclear weapons.

On many occasions, Father Hesburgh found himself the first

Catholic priest to serve in a given leadership position on boards of secular

organizations. Much of his success can

be viewed as stemming from his ability to distance himself from the authority

of the Church. Such was the case during

the years he served as a trustee, and later, Chairman of the Board of the

Rockefeller Foundation, a frequent funder of causes counter to Church

teachings—including population control.

Some of Father Hesburgh’s activities are

curiously missing from the Notre Dame website’s formal

biography of their beloved president emeritus.

Zombies Are Not Fast (But They Can Be Boring)

A review of World War Z,

a movie about zombies that is not interested in zombies. | Nick Olszyk | Catholic World Report

MPAA Rating, PG-13

USCCB Rating, A-III

Reel Rating,

(2 out of five)

(2 out of five)

Zombies are among the

greatest MacGuffins in contemporary literature and cinema. Any

thoughtful examination of the subject of the living dead leads

nowhere, but zombies can be a stand-in for any number of important

social issues including immigration, natural disasters, and even

romantic tension (see Warm Bodies).

Zombie movies generally fall

into two categories: scary thrillers only interested in seeing

screaming teenagers killed in horrific ways or thoughtful

examinations about society and human nature. World War Z wants

to be in the second category but tries to also placate those who like

the first. As a result, neither is fully realized. Its attempt to say

something productive about life and death is compromised by the

repetitive need to show millions of CGI zombies attacking people.

World War Z makes zombies boring.

Gerry Lane (Brad Pitt) is a

modern day Cincinnatus who once fought third-world conflicts for the

United Nations and now makes pancakes every day for his kids while

his loving wife brings home the bacon. Then the zombie apocalypse

breaks out in terrifying fashion. Gerry’s training comes in handy

as his family fights its way through Philadelphia until they are

rescued and brought to safety on aircraft carrier in the Atlantic (it

is usually assumed that zombies cannot swim).

His family’s lodging comes

at a price; Gerry must travel around the world looking for the origin

of the outbreak in order to make a vaccine. As Gerry chases down

answers from South Korea to Israel to Wales, he is continually

pursued and attacked by zombies. The amount of actual time taken to

move the plot forward is minuscule and many interesting facets of

this story are overlooked in the service of pure, adrenaline-laced

action. The film ends with a discovery that provides humanity with a

sliver of hope but does not solve the seemingly endless problem.

For most of a person’s

life, he assumes that tomorrow will come; safety is the rule, not the

exception. Yet for those who have experienced a serious illness or

been in a significant car accident, an understanding comes of the

truth: death is a possibility at every moment and eternity is much

longer than our lifespan. Jesus explained this by saying, “there

will be two men in a field. One will be taken, the other left.”

World War Z does a good job of demonstrating this sobering

fact. The scientist Dr. Fassbach states that “mother nature is a

serial killer” and explains that the Spanish flu killed nearly 3%

of the world’s population in two years.

Yet all of these

apocalyptic scenarios never ultimately come true.

July 2, 2013

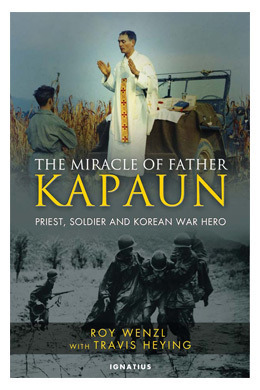

The Introduction to "The Miracle of Father Kapaun"

The Introduction to The Miracle of Father Kapaun: Priest, Soldier and Korean War Hero | Roy

Wenzl

Some

people regard the meek man as one who will not put up a fight for

anything but will let others run over him. . . . In fact from human

experience we know that to accomplish anything good a person must

make an effort; and making an effort is putting up a fight against

the obstacles. — Father

Emil Kapaun

Emil Kapaun is a rare man. The Vatican is

considering whether the priest deserves to be canonized a saint, and

the president of the United States is pondering whether the soldier

is worthy of the Congressional Medal of Honor.

[Editor's note: Since the publication of The Miracle of Father Kapaun, President Obama awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor posthumously to Fr. Kapaun.]

There was

nothing remarkable about Emil Kapaun’s childhood or early manhood

to suggest that he would become a Korean War hero and might someday

be declared a Catholic saint. He grew up on a farm in Kansas, where

he was born in the kitchen on April 20, 1916. His parents were pious

and hardworking, but so were lots of farmers in America’s

heartland.

Kapaun was a good student at the local public

school and later at an abbey high school and college, but with his

quiet and unassuming manner he did not stand out as exceptional. His

early priesthood and military chaplaincy were uneventful.

When

we began the research for Kapaun’s story, the chief investigator of

his cause for sainthood confided some concerns about his own work.

Rev. John Hotze had spent a decade investigating Kapaun for the

Vatican. He said one of the frustrating things about talking to

Kapaun’s Catholic supporters

is that many of them used clichés to describe

him—surrounding

the man’s actions with choirs of angels

singing

and playing harps: “He was such a holy man.”

Years ago,

some initial Church investigators appeared to

seek

the same type of descriptions when they questioned

Kapaun’s

fellow prisoners of war. They asked those survivors

of

North Korea’s POW camps whether Kapaun prayed fervently”

every day; whether he was “holy” at all times;

and

whether dying soldiers got up and walked immediately

after

Kapaun had laid his hands on them. Although the questions

irritated

Kapaun’s battle-scarred friends, they answered

them

politely enough.

The Kapaun these friends remembered, however,

was no

painted-plaster

saint. He was a regular guy. He did ordinary

things.

And he stank and looked dirty because the POWs

never

got to bathe.

Kapaun saved hundreds of lives, said Lt. Mike

Dowe, but

not

“by levitating himself two feet off the ground”. He did

practical

things, such as boiling water and picking lice—

tasks

that can seem small but that made a huge difference

for

malnourished and sick POWs. The mostly soft-spoken

man

had a temper, Dowe recalled, and he sometimes used

colorful

language to get his point across.

This gritty reality was just

the kind of thing Hotze intended

to

track down, he explained to us, as clichés would not do

the

job. Andrea Ambrosi, the Vatican investigator who helped

Hotze

prepare Kapaun’s documents for the Vatican, had told

him

that Rome wanted the real Kapaun—warts, rags and all.

The

job appealed to Hotze, a Wichita Diocese priest

who

tells good stories in his Sunday homilies. Hotze knew

that

many great saints down through the ages had been

bad

boys before their conversions. Paul and Augustine:

notorious.

Francis of Assisi: as fond of ladies as he was of

wining

and dining. Although not everyone makes a dramatic

180-degree

turn on his way to his best self, every

man

is in need of conversion; each one has weaknesses

and

has done things he regrets. Hotze thought the flawed

Kapaun

would be not only more believable, but more able

to

offer hope to those who struggle to overcome their

failings.

Hotze

gathered for the Vatican stories about Kapaun told

by

non-Catholic POWs—the Protestants, Jews, agnostics and

atheists

who had no qualms about relating the priest’s foibles.

And

so far, Rome has given Kapaun the title Servant

of

God, the first of four steps toward canonization.

Hotze’s

approach shaped the way we wrote our own story for

the Wichita

Eagle in

2009. We too wanted to show Kapaun

as

he really was.

This book is based on what Kapaun’s fellow

soldiers told

photographer

Travis Heying and me about the priest’s actions

in

the Korean War. Although we went in search of the real

man,

we nevertheless heard stories about Kapaun that

sounded

miraculous, and for newspaper reporters and editors,

the

miraculous creates challenges. What soldiers say

Kapaun

did is so heroic that it defies believability. He saved

hundreds

of lives, they say, while placing his own at risk.

How

could such a story be written credibly?

Travis and I began our

research by calling Dowe, Herb

Miller

and Kapaun’s other prisoner-of-war friends in June

2009.

We drove or flew all over the United States to talk

with

them. We saw firsthand that they had suffered deeply.

They are

still suffering. They choked up sometimes as they

told

us what they had experienced.

We admired these veterans, but

still we wondered whether

they

had embellished their stories over sixty years of steaks

and

beers at POW reunion banquets.

One thing that convinced us

that Kapaun’s friends were telling

us the truth was that they demanded we tell

the truth in

what we wrote about him. And we found consistency

between

what they said and the letters and recorded testimonies

that

the guys had given about Kapaun over the years.

Kapaun’s

friends do not consider themselves experts on

miracles,

but they know what they saw, and as far as they

are

concerned, the man himself was something like a miracle.

By

the time we talked to most of them, the secretary

of

the army and the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff

had

learned enough about the already decorated U.S. Army

captain

to recommend him, posthumously, for the highest

military

honor in the United States. The Pentagon is in

the

business of declaring war heroes, not saints. But to

many

of Kapaun’s eyewitnesses, they amount to the same

thing.

One

of the striking things we learned about Kapaun was

how

little he said on any given day. In civilian life, as in

camp,

he listened more than he talked. He almost never

preached.

The chaplain did not even bring up the subject

of

prayer without permission.

On the march, Kapaun sometimes

didn’t bother to introduce

himself

to fellow soldiers as a chaplain or even as an

officer.

Instead he would throw himself into whatever task

they

were doing. And then, after the men saw him work

harder

than any other guy, he would ask whether there was

anything

more he could do for them, including praying with

them.

Some

soldiers didn’t care for chaplains, considering them

Holy

Joes who sermonized while grunts did the dirty work.

But

they liked Kapaun a lot, and one reason was that he

made

himself one of them. His way of witnessing Jesus was

to

spare the platitudes and dig foxholes or latrines alongside

sweating

soldiers.

Another reason the men liked Kapaun was that he

treated

everyone

with respect. He showed Protestants, Jews, Muslims

and

nonbelievers the same kindness he bestowed on

Catholics.

Kapaun’s friends said this quality stuck out because

many

people, even many practicing Christians, fail in showing

regard

to those different from themselves. When Kapaun

died,

the Muslim Turks in camp revered him as much as

anybody

else did.

That’s who Father Kapaun was. And we know now how

he

got that way.

In that Kansas farmhouse where he grew up,

Kapaun had

read

the Gospels by kerosene lamplight. In those pages, he

had

found a hero to imitate—the Jesus who claimed he was

divine

but who walked among ordinary men, healing them,

feeding

them, standing up for the weakest among them and

dying

for them. Jesus won people over more with actions

than

with words.

In a homily Kapaun prepared for Palm Sunday 1941,

while

he

was still a young parish priest, he wrote that if a crisis

ever

came, a person who wants to help others should imitate

Christ.

And that’s what Father Kapaun did.

July 1, 2013

Freedom from Government (Birth) Control

Freedom from Government (Birth) Control | Carrie Gress | Catholic World Report

An interview with Helen Alvaré of Women Speak for Themselves

Washington, DC – More than 40,000 women are putting religious freedom

ahead of the political fiction that says all women want free

contraception, sterilization, and abortifacients.

The group, Women Speak for Themselves,

was founded by Helen Alvaré and Kim Daniels in response to the Health

and Human Services mandate for insurers to provide contraception,

sterilization, and abortifacients at no cost to their clients.

Catholic World Report caught up with Helen Alvaré to find out more about what this growing group of women is doing to fight the HHS mandate.

Alvaré is a professor of law at George Mason University, a consultor to

the Pontifical Council for the Laity, a consultant for ABCNews, and the

chair of the Conscience Protection Task Force at the Witherspoon

Institute. She co-authored and edited the book, Breaking Through: Catholic Women Speak For Themselves.

CWR: What is “Women Speak for Themselves” and how did it come about?

Alvaré: It came about because I was shocked and

dismayed that the news reports about the response to the HHS mandate, as

well as the words out of the mouths of some members of Congress,

claimed that this HHS mandate fight was women vs. men. And bad men,

particularly religious men, hated women and therefore opposed the

mandate. I knew that this was untrue in my own situation and I knew many

women who would feel the same.

The news reports were pouring in on February 16, 2012, and I decided

that I should draft an open letter. I bounced it back and forth with my

good friend Kim Daniels, who is a religious liberty attorney, and we

crafted it and sent it out to a couple of dozen friends and asked for

signatures. This cascade of signatures started to come in so that in

about 48 hours we had about 2,500, and by the end of the week we had

7,500. We hadn’t done any asking beyond that original couple dozen

women, so we knew there was an untapped, unvocalized sentiment out

there. We expressed it in two points: one is that women particularly

care for religious freedom and second, the idea that contraception

equals women’s freedom and trumps religious freedom was simplistic and

wrong.

It has now grown to about 40,000-41,000 women online with whom I

correspond about every three weeks to keep them up-to-date on things

that affect the mandate and religious liberty, but increasingly things

that affect the whole plane that basically says the ability to express

yourself sexually is the biggest part of women’s freedom.

CWR: What is the current situation with the HHS ruling?

Continue reading on the CWR site.

June 29, 2013

Jesus, Marriage, and Homosexuality

Jesus, Marriage, and Homosexuality | Leroy Huizenga | CWR

The early Christians, following the lead of Jesus, doubled down on traditional Jewish sexual morality.

In the wake of the Supreme Court’s

decisions striking down the substance of the Defense of Marriage Act

(DOMA) and California’s Proposition 8, Jesus’ opinion—or lack

thereof—on homosexuality has received renewed attention. In a crass

fundraising email running the risk of violating the Second

Commandment, Mike Huckabee wrote, “My immediate thoughts on the

SCOTUS ruling that determined that same sex marriage is okay: ‘Jesus

wept,’” while social media ran rampant with memes of Catholic

comedian Stephen Colbert’s words from a show in early May 2012:

“And I right now would like to read to you what the Jesus said

about homosexuality. I’d like to, except he never said anything

about it.”

Colbert’s claim

is common, and it’s effective because it’s true: Jesus did not

directly address the matter. But it does not follow that

Jesus’ words and example have no relevance for marriage, sex, and

family, nor that modern Christians should approve of gay marriage. A

few observations:

First,

Jesus was

a Jew who inherited Jewish Scripture and tradition. Jesus

did not drop out of the sky to bring a brand new set of moral

teachings de

novo. If

he did, perhaps his apparent lack of attention to sex and sexuality

would be striking. But the Jesus of the Gospels—especially Matthew,

the First Gospel in so many significant ways—is a conservative Jew,

as was in all likelihood the so-called historical Jesus behind the

Gospels. And whether we're talking about the historical Jesus or the

Jesus of the Gospels, Jesus stands well within the breadth of Jewish

tradition. Thus, it's not true that things Jesus doesn't spend an

inordinate amount of time on or doesn't mention are unimportant.

Rather, we should assume that those things in Jewish tradition which

Jesus doesn't overturn or reinterpret are assumed. Sure, Jesus

doesn't outright forbid homosexual practices in the Gospels. But he

doesn't have to, because Jesus' Judaism did.

Assuming

that religion is a matter of prohibitions, in debates over sexuality

people often assume that Jesus came simply to forbid

certain behaviors, and if he didn't forbid something, it's therefore

licit. The principle would be "Scripture permits anything not

expressly forbidden." But why assume that hermeneutical posture?

The mission of the prophets and the resolution of the Messiah

A Scriptural Reflection on the Readings for June 30, 2013, the Thirteenth Sunday in

Ordinary Time | Carl E. Olson

Readings:

• 1 Kgs 19:16b, 19-21

• Ps 16:1-2, 5, 7-8, 9-10, 11

• Gal 5:1, 13-18

• Lk 9:51-62

“I’m on my way!” “We’re on

our way!”

These are common enough expressions, and we know

their meaning. They indicate movement, purpose, resolution. We’ve

uttered them many times, with anticipation, or with anxiety.

Jesus, we hear in today’s Gospel

reading, was “on the way.” The days for his “being taken up”

had been fulfilled, and so “he resolutely determined to journey to

Jerusalem.” A more direct translation is that “he hardened his

face to go”. This language is meant to evoke connections with the

prophets, especially Ezekiel: “Son of man, set your face toward

Jerusalem and preach against the sanctuaries; prophesy against the

land of Israel…” (Ezek. 21:2; RSVCE). Jesus sent messengers

ahead, reminiscent of God sending messengers before Moses and the

people (Ex. 23:20).

The journey to Jerusalem was, in other

words, a prophetic mission and the concrete realization of a new

Exodus—not from Egypt, but from sin, death, and separation from

God. Jesus was resolute and unflinching in this decision, by which

“he indicated that he was going up to Jerusalem prepared to die

there” (Catechism of the Catholic Church, par. 557). Some

have suggested or insisted that Jesus, in going to Jerusalem, did not

really know of his approaching death, but was acting with naïve

optimism or blind faith.

However, as we heard last week, Jesus

told his disciples that he would suffer, be rejected by the religious

leaders, killed, and raised on the third day (Lk. 9:22). What the

prophets of the Old Testament sometimes saw in startling glimpses,

Jesus saw with calm clarity: his mission was to liberate mankind from

the slavery of sin and the curse of death by being the sinless,

sacrificial Lamb of God. And as the Holy One journeyed to the holy

city, he encountered rejection, opposition, confusion, and even

fervent promises—the same reactions he still encounters today.

The Samaritans, whose harbored strong

hostility toward the Jews, did not welcome him, apparently because he

journeyed to Jerusalem and not Mount Gerizim, the site of their

temple (cf. Jn. 4:20). Jesus did not fit their concept of a prophet

or messiah, and so they rejected him. Of course, the Pharisees and

scribes also rejected him for the same reason, and the similarities

(and irony) of this fact was likely not lost on St. Luke’s

first-century readers.

Jesus then encountered three men who

got a taste (and give us a clear picture) of the demands of

discipleship. It is easy to say to Jesus, “I will follow you

wherever you go,” but keeping such promises is far more daunting

than making them. Another asked to be given time to first bury his

father; a third wished to first say goodbye to his family.

Was Jesus insensitive to familial

responsibilities and hardships? No, said St. Basil the Great, but “a

person who wishes to become the Lord’s disciple must repudiate a

human obligation, however honorable it may appear, if it slows us

ever so slightly in giving the wholehearted obedience we owe to God.”

Jesus recognized that these men, well intentioned and fervent as they

may have been, were like those who “receive the word with joy, but

they have no root; they believe only for a time and fall away in time

of trial” (Lk. 8:13).

As St. Frances de Sales wrote, in

Treatise on the Love of God, “…we receive the grace of God

in vain, when we receive it at the gate of our heart, and not within

the consent of our heart; for so we receive it without receiving it,

that is, we receive it without fruit, since it is nothing to feel the

inspiration without consenting unto it.” Contrast that with the

newly selected prophet, Elisha. Called by God, he asked permission to

say farewell to his family. Rebuffed by Elijah, he literally

sacrificed his old life, recognizing that following God requires

going all the way.

His actions said, “I’m on the way.”

What do our actions say?

(This "Opening the Word" column originally appeared in the June 27, 2010, issue of Our Sunday Visitor newspaper.)

June 28, 2013

Giving thanks for the separation of Church and State

by Russell Shaw | Catholic World Report

In the question period after a talk

I'd given on my new book, American Church, a woman raised an

important point: "If the Church in the U.S. faces as many

problems as you say, why is it doing so much better here than in much

of Europe?"

Great question. My answer--which I

also give in the book--was along these lines.

"It has a lot to do with the

First Amendment principle of separation of Church and State. Yes, I

know--'separation' sometimes is used as a club by secularists who

want to drive religion out of the public square. But on the whole

it's been a great blessing for the Church and for religion in

America.

"For one thing, church-state

separation has generally kept government out of religious affairs,

while also keeping clerics out of inappropriate involvement in

politics. In combination with Cardinal Gibbons' wise decision to

embrace the emerging labor movement in the late 19th century, this

spared the Church the sort of virulent anticlericalism found in

countries like France, Spain, and even 'Catholic' Ireland as a

reaction against the political clericalism of the not so distant

past."

Almost always, I might have added,

clericalism breeds anticlericalism. That we've largely escaped the

worst sort of clericalism in America means we've also been spared the

worst sort of anticlericalism.

But granted all that, the situation of

the Catholic Church in America today is increasingly perilous.

American Church explains why. In brief, the explanation goes

like this.

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers