Carl E. Olson's Blog, page 150

May 27, 2013

So Many Jesuses, So Little Time

So Many Jesuses, So Little Time |

John Buescher | Catholic World Report

Countless attempts to rewrite and revise the life of

Christ aim at destroying belief in objective truth

“Now Jesus did many other signs in the presence of the

disciples, which are not written in this book; but these are written that you

may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that believing you

may have life in his name.” (John 20:30-31)

This scripture passage, I think, contains a hint: What you need to know about Jesus is in

the Gospels. If you find them or

what the Church says about them unsatisfying or in need of much supplement in

order to sufficiently understand or appreciate Him, it is a probably sign that

you are chafing under His yoke, and that you are itching to throw it off altogether. Your newly-found “background” and

“context” for Jesus will color Him, until He will fade away and disappear.

Lew Wallace once commented on writing his 1880 novel, Ben-Hur:

I first determined to withhold the

reappearance of the Savior until the last hour. I would have him always on the point of coming, that His

appearance might be looked for, to-day just over the hills, to-morrow at the

summit, with the hosts looking for him, tearfully yearning for his presence. My next resolve was that He should not

actually figure in any scene, and my only violation of this was when the cup of

water was given to Ben Hur at Nazareth.

A third purpose was to have every word which he supposedly uttered, the

exact words of sainted biographers.

Why was he so wary about portraying Jesus? Because, as he explained, “The

Christian world would not tolerate a novel with Christ as its hero.” Such a world would not tolerate

endangering the sacred by shading it with profane colors. So he wrote a novel about the world

around Jesus, but left Jesus himself as the mysterious untouched center.

The Many Lost Lives of Jesus

But whether Wallace was right about the Christian world of

the time is more difficult to say.

In a sense, this had already been done to wide acclaim by Ernest Renan

in his 1863 sentimentalized Life of Jesus,

although Renan and most of his readers would not have recognized it as fiction

but simply as a colorful retelling of the Savior’s life.

As Albert Schweitzer wrote about Renan in The Quest for

the Historical Jesus:

May 26, 2013

"The Creed and the Trinity" by Henri de Lubac, SJ

The Creed and the Trinity | Foreword to The Christian Faith: An Essay on the Structure Of the Apostles' Creed | Henri de Lubac

This book does not pretend to impart any information to the learned historians of the creeds, save that, for better or worse, the author has often made use of their works. Nor does it deal in depth with any of the current theological problems, although it does not avoid alluding to them in passing. Nor should one seek in this book a systematic study of trinitarian doctrine or Christology. Its purpose is not even, at least not directly, pastoral. Rather, we have tried to make it a sort of introduction to catechesis, addressed to all those who, either in preparing candidates for baptism or in teaching children or in day-by-day preaching to the Christian people, are entrusted with this most beautiful of all roles: handing on the faith received from the Apostles, always and infinitely fruitful even as it was when they themselves received it from Jesus Christ. Like everyone else, the believer is able to observe the changes, slow or sudden depending on the times, in people's mentalities and interests, the variations that occur in language. Without becoming enslaved to theories (themselves subject to so many vicissitudes) that seek to account for these changes, he does not necessarily remain insensitive to the repercussions of this historical development of culture or cultures upon theological work and even, on occasion, upon the very expression of his faith. If he himself is not conscious of it, the Magisterium guides him to make him understand that in certain circumstances renewal is necessary and that one would be condemned to wither and die if one did not ever consent to adapt or change anything. But at the same time he sees with great clarity that the treasure he has received as his inheritance is not the fruit of a perishable culture. The Christian tradition, that living force in which he shares, is rooted in the eternal. If he strives to be faithful, the newness that rejuvenates his heart is not exposed to the erosion of time. Consequently he is not in the least tempted to a certain kind of forced advance in which a number of those around him are indulging. He can only see in that, as Pascal would say, a confusion of orders. He knows in advance: in the letter of the Creed which he recites with his brothers, following so many others, there is infinitely more depth in reserve and timeliness in potential than in all the explanations and critical reductions that would affect to "go beyond" it. He knows this in advance, and experience and reflection reveal it to him a little more each day.

Like everyone else, the believer is able to observe the changes, slow or sudden depending on the times, in people's mentalities and interests, the variations that occur in language. Without becoming enslaved to theories (themselves subject to so many vicissitudes) that seek to account for these changes, he does not necessarily remain insensitive to the repercussions of this historical development of culture or cultures upon theological work and even, on occasion, upon the very expression of his faith. If he himself is not conscious of it, the Magisterium guides him to make him understand that in certain circumstances renewal is necessary and that one would be condemned to wither and die if one did not ever consent to adapt or change anything. But at the same time he sees with great clarity that the treasure he has received as his inheritance is not the fruit of a perishable culture. The Christian tradition, that living force in which he shares, is rooted in the eternal. If he strives to be faithful, the newness that rejuvenates his heart is not exposed to the erosion of time. Consequently he is not in the least tempted to a certain kind of forced advance in which a number of those around him are indulging. He can only see in that, as Pascal would say, a confusion of orders. He knows in advance: in the letter of the Creed which he recites with his brothers, following so many others, there is infinitely more depth in reserve and timeliness in potential than in all the explanations and critical reductions that would affect to "go beyond" it. He knows this in advance, and experience and reflection reveal it to him a little more each day.

Above all, this Creed teaches us the mystery of the divine Trinity. It is in this mystery that our faith consists. It is for us both light and life. Nevertheless, it is very necessary for us to recognize that this is not always easy to understand and is not readily apparent to everyone. For a number of Christians, and not just those who retain only a vague, conventionalized version of their faith, this seems to be a sealed mystery. Is it proper to blame those who have the task of instructing us? It would be more just to take this blame upon ourselves. We do not always know how to embrace the most pregnant truth, which must slowly produce its fruit within us. Impatient as we are, we would like to understand immediately, or rather, in our shortsighted pragmatism, if we are not shown practical applications for it right away, we declare it to be abstract, unassimilable, "unrealistic", an "empty shell", a hollow theory with which there would be no point in burdening ourselves.

This is what Faustus Socinus and his disciples thought, as witnessed by their Catechism of Racow (1605): "The dogma of the Trinity is contrary to reason. It is absurd to think that by the will of God, who is reason and who loves his creatures, men must believe something incomprehensible and useless to moral life and therefore to salvation." This was also the opinion of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, agreeing in this respect with all the Christians of his century seduced by the "lights": the Trinity, in the judgment of the Savoyard Vicar, was a part of those things that "lead to nothing useful or practical". Now we must really be convinced that, when we allow ourselves to indulge in such thoughts, it is we who are thus living superficially, outside of ourselves. The Christian who does not trust the fruitfulness of revealed truth, who consents to interest himself in it only to the degree to which he perceives the benefit in advance, who does not consent to let himself be grasped and modeled by it, such a Christian does not realize of what light and power he has deprived himself. [1] He does not see that in consenting to hear--if it may be called that--only the voices that promise him a response to his immediate questions, he is himself renouncing the opportunity to grow in self-understanding and depth while shutting himself up within the limits of his own narrow experience. Sometimes he even reaches the point of imagining he can no longer find any meaning in a hackneyed, "out-of-date" concept, when in fact he is dealing with a mystery he has not yet glimpsed.

The revelation of the trinitarian mystery turned the world upside down. Not after the fashion of human, political, social or, to use the current jargon, "cultural" revolutions which mark the course of history; but by opening up within man himself new depths, definitive depths, which he must thenceforth never cease to explore. By transforming totally his idea of the divinity, it at the same time transformed man's understanding of himself. More precisely, it revealed him to himself and transformed him. The transcendence of this mystery is total, and precisely for that reason its light can plumb the depths of our being. If I speak as one who believes in the Most Holy Trinity, then "I do not speak of it as I might of a constellation lost somewhere in the limitless reaches of space, but I see in it the first principle and the last end of my own existence; and my belief in this supreme mystery includes me too." [2] It includes me, it includes all of us. By this faith the Church of Jesus Christ lives. [3] If, instead of getting caught in that pathetic masochism into which so many perverse prophets work unceasingly to plunge them, Christians truly resolved to believe--I mean, to trust in their faith--this faith would in all truth make of them today the soul of the world.

Our God is a living God, a God who, in himself, is sufficient unto himself. In him there is neither solitude nor egoism. In the very depths of Being there is ecstasy, the going out of self. There is, "in the unity of the Holy Spirit", the perfect circumincession of Love. Thus we can glimpse the depths of truth in St. John's remark (which is not true vice versa) that "God is love." If we exist, it is not due to chance(!) or to some blind necessity; nor is it the effect of a brutal and domineering omnipotence; it is in virtue of the omnipotence of Love. If we can recognize the God who speaks to us and wishes to link our destiny to his, this is because within himself he knows himself eternally; within his being a dialogue exists which can overflow without; he is animated by a vital movement with which he can associate us. If, even without philosophical training, we can resist those who tell us that matter is the ground of all being, and if we spontaneously go beyond the overly abstract views of those who tell us that spirit, or the "one", is the ground of being, it is because this mystery of the Trinity has opened up before us an entirely new perspective: the ground of all being is communion. [4] If we are able to overcome all the crises which might lead us to despair of the human adventure, it is because by the revelation of this mystery we know that we are loved. And at the same time we learn what the most clearsighted among men are inclined to question: we learn that we ourselves can love; we have been made capable of doing so by the communication of divine life, that life which is love. We thereby understand also how "the fullness of personal existence coincides with the fullness of the gift", how self-realization without the gift of self is a delusion, and how, on the other hand, the gift of self goes astray into aimless activism if it is not the overflow of an inner life. We know, finally, that we must yield to this desire for bliss which no theory, no negation, no despair will ever tear out of the human heart because, far from being the pursuit of one's own interest, it blossoms under the action of God's Spirit into a hope of loving even as God loves.

If, as explained in the following pages, the mystery of the Trinity is not revealed to us first of all in itself but in the Trinity's action outside of itself, in its saving activity, it is no less true that the term of that saving action is indeed, already, the Trinity itself, glimpsed by faith in its very essence--even though always veiled in mystery, in umbris et imaginibus. So the "Trinity in itself" is still, even now, "the Trinity in relationship with us". Trinitarian doctrine is not the brainchild of some solitary thinker; it comes from the revelation of Jesus Christ. Nor is it a result of "high theological speculation". It is not a secret "reserved to the learned professionals, but it has an effective importance for every Christian". [5] Our inner existence, our personal relationships, our social action, our research and our efforts toward Christian unity, the entire basic orientation of our thought and life will be right and fruitful in proportion as they are in conformity with the reality of this mystery.

The mystery of the Trinity, which sheds light on the mystery of human existence, is wholly contained in the mystery of Christ. For this reason, as we well realize, another work would be necessary to introduce this one. It would start with the very first formulations of the Christian faith, which are Christic formulas. In Jesus Christ, God has opened his heart to us. Through him, "the Mediator of revelation and also its fullness", the Good News was proclaimed and will never cease to be heard. "A day has dawned which will know no ending. It comes to us out of the obscurity of Nazareth and reaches down to us through the centuries; it leads us on beyond all time . . . even to the very Center of truth. Hope has already begun; it can no longer end." [6]

ENDNOTES:

[1] "The life of the Church is more reliable than our own judgment. It is necessary to trust it, and experience does not hesitate to enlighten in this regard the one who lives his faith simply and profoundly": Cardinal G. M. Garrone, Que faut-il croire? (Paris: Desclée de Brouwer, 1967), 45.

2 Romano Guardini, Vie de la foi (Paris: Éd. du Cerf, 1968), 48.

[3] Cf. Origen, In Exodum, hom. 9, no. 3: "Funis triplex non rumpitur, quae est Trinitatis fides, de qua pendet et per quam sustinetur omnis Ecclesia" (Éd. Baehrens, 239).

[4] Jean Daniélou, La Trinité et le mystére de l'existence (Paris: Desclée de Brouwer, 1968), 53. "It is hard to believe that Christians who possess the ultimate secret of things, who are the only ones able to penetrate, by the light of Christ, into the abyss of the hidden mystery that envelops all things, should not be more aware of the fundamental importance of the message they have to convey."

[5] Cf. Timothy Ware, L'Orthodoxie, French trans. Charité de Saint-Servais (Paris: Desclée de Brouwer, 1968), 285.

[6] Jean Ladriére.

Related IgnatiusInsight.com Articles and Excerpts:

• Ignatius Insight Author Page for Henri de Lubac

• Are Truth, Faith, and Tolerance Compatible? | Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger

• Why Do We Need Faith? | Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger

• The Ministry of the Bishop in Relation to the Blessed Trinity | Cardinal Francis George, O.M.I

• The Reality of God": Benedict XVI on the Trinity | Fr. James V. Schall, S.J.

• • Eternal Security? A Trinitarian Apologetic for Perseverance | Freddie Stewart, Jr.

• Jean Daniélou and the "Master-Key to Christian Theology" | Carl E. Olson

• God's Eros Is Agape | Fr. James V. Schall, S.J.

• First Musings on Benedict XVI's First Encyclical | Fr. Joseph Fessio, S.J.

• Some Comments on Deus Caritas Est | Mark Brumley

• Love Alone is Believable: Hans Urs von Balthasar's Apologetics | Fr. John R. Cihak

• Understanding The Hierarchy of Truths | Douglas Bushman, S.T.L.

Henri de Lubac, S.J. (1896-1991) was a French Jesuit and one of the greatest theologians of the twentieth century. De Lubac was ordained a priest on August 22, 1927, pursued further studies in Rome until 1929, and then became a faculty member at Catholic Faculties of Theology of Lyons, where he taught history of religions until 1961. His pupils included Jean Daniélouand Hans Urs von Balthasar. De Lubac was created cardinal deacon by Pope John Paul II on February 2, 1983 and received the red biretta and the deaconry of S. Maria in Domnica, February 2, 1983. He died on September 4, 1991, Paris and is buried in a tomb of the Society of Jesus at the Vaugirard cemetery in Paris. For more about his life and a listing of his books published by Ignatius Press, visit his IgnatiusInsight.com author page.

"The Trinity and the Nature of Love" by Fr. Christopher Rengers

The Trinity and the Nature of Love | Fr. Christopher Rengers | From the November 2007 issue of Homiletic & Pastoral Review

It is only through revelation that we have come to know that God is one and three. To understand the doctrine completely is beyond human ability. But to explore the Holy Trinity by appealing to reason and human experience is very worthwhile.

In fact, the Trinity, as the struggles of the first centuries of Christianity show, must be discussed in order to define who Jesus is and why Mary may be called Mother of God. Our most common Christian gesture and the words that go with it in the Sign of the Cross turn our thoughts to the Trinity. This simple practice presents us with contrasting mysteries, bringing together suffering, mortal human nature and unchangeable, eternal divine nature. The tracing of the cross points to painful death while the words point to the source of all life, the Holy Trinity.

Prayerful contemplation, discussion and exploration have a continuing purpose. The fullness of all life, creativity and power that is in the Trinity provides ever-expanding horizons for contemplation, thought and incorporation in helpful, practical ways into human life. Two "explorers" almost a millennium apart offer viewpoints of unique interest. They are the little-known Richard of St. Victor and our present Holy Father, Benedict XVI. The latter's work An Introduction to Christianity [1] appeared originally in German in 1968, and is not magisterial teaching. It is rather the product of a profound philosopher and theologian. It delves into the ultimate nature of reality in the Trinity and the ultimate meaning of person.

The chapter "Belief in the Triune God" makes a helpful comparison between the nature of matter as now conceived in physics and the nature of substance and relation in the Trinity. The phrase quoted to explain the structure of matter as "parcels of waves" brings the comparison into focus.

The phrase is open to criticism in regard to physics, "but it remains an exciting simile for the actualitas divina, for the fact that God is absolutely 'in act' (and not 'in potency'), and for the idea that the densest being—God—can subsist only in a multitude of relations, which are not substances but simply 'waves,' and therein form a perfect unity and also the fullness of being" (p. 175).

The position of the observer has much to do with what he will discover. The question the observer asks will have an effect on the answer. The physicist doesn't approach everything as though it had to be matter. Nor does he approach everything as though it had to be motion. He looks at the total reality from two viewpoints. One is that things are made of matter, the second that everything is arranged according to motion or "waves." It is necessary to think in complementarities, whether in physics or in the theology and philosophy of the Trinity.

So in approaching the Trinity we consider it according to substance and according to relationship. The two together taken complementarily will give the complete reality that is the Holy Trinity. The relatededness cannot be considered as an accident of the substance. Putting the two together expresses the reality that is defined as one God and three divine Persons. "Not only unity is divine; plurality, too, is something primordial and has its inner ground in God himself. ...It corresponds to the creative fullness of God, who himself stands above plurality and unity, encompassing both" (pp. 178-179).

Faith enters into the observer's viewpoint

What is said so far concerns chiefly the area of logic and philosophy. But the Christian has a re-enforced position. It comes from the gift of faith. The Christian too is an observer, but his vantage point brings in the powerful beam of faith to shine on the total reality of the Holy Trinity.

Pascal's famous argument of the wager is highly praised. The argument has "an almost uncanny clarity and an acuteness verging on the unbearable" (p. 176). The man of no faith is, after a series of questioning, finally driven into the corner of accepting or rejecting belief. The punch line is in the final advice to a man of no faith: "You want to cure yourself of unbelief and you ask for a remedy? Take a lesson from those who were earlier racked by doubts like yourself.... Follow the way by which they began; by acting as if they believed, by taking holy water, by having Masses said and so on. This will bring you quite naturally to believe and will stupefy you." Stupefy is here explained as returning to the openness of a child, not hindered by pride of intellect. "On this basis, Brunschvieg can say in Pascal's sense, 'Nothing is in more conformity with reason than the disavowal of reason'" (pp. 176-177).

What does "person" mean?

As far as a human being is concerned, a person is an individual, rational, responsible substance. Relationship to others is something added. Our usual concept of "person" is anthropological. This concept, of course, makes difficulties when thinking of the divine "Persons." In them "person" is not an individual substance, but is a co-element of their total reality. The apt phrase,parcels of waves, to express the structure of matter as a grouping of certain motions or "waves," helps in grasping this fact. In God the substance and the "waves," or relatedness, are both necessary on an equal basis for conveying the proper notion of the total reality that is God, three and one, the Holy Trinity.

The relationship "stands beside the substance as an equally primordial form of being....The 'three Persons' who exist in God are the reality of word and love in their attachment to each other. They are not substances, personalities in the modern sense, but the relatedness whose pure actuality ('parcel of waves'!) does not impair the unity of the highest being but fills it out" (p. 183).

"St. Augustine once enshrined this idea in the following formula: He is not called Father in reference to himself but only in relation to the Son; seen by himself he is simply God. Here the decisive point comes beautifully to light. 'Father' is purely a concept of relationship. Only in being for the other is he Father. In his own being in himself he is simply God. Person is the pure relation of being related, nothing else. Relationship is not something extra added to the person, as it is with us; it only exists at all as relatedness. (p. 183)

"Let us listen once again to St. Augustine: In God there are no accidents, only substance and relation. Therein lies concealed a revolution in man's view of the world: the sole dominion of thinking in terms of substance is ended; relation is discovered as an equally valid primordial mode of reality" (p. 184).

Trinity doctrine is most practical

It has been said that saints and great contemplatives end up giving more and more attention to the Holy Trinity. This does not mean that they are up in the ozone of a spirituality detached from ordinary human life. It means the contrary. To understand that relatedness does not destroy but adds to unity, and indeed is necessary for perfect unity, has practical conclusions for human life. Fullness of human life too flows from relatedness, and will be more pleasing and perfect the more the person's self-giving and other-receiving proceed from love.

In the Trinity self-giving and other-receiving is of course perfect and so unity is perfect. But Jesus has called all his followers to imitate that oneness. In his sublime prayer at the Last Supper (John 17), he prayed first for the Apostles and then specifically for all they would in turn invite to follow him: "Yet not for these only do I pray, but for those who through their word are to believe in me, that all may be one, even as thou, Father, in me and in thee; that they may also be one in us, that the world may believe that thou hast sent me" (20-21).

Before his priestly prayer Jesus had made clear that the great demand for unity made on them could be fulfilled only by the coming of the Third Person of the Trinity. Jesus would send him. But again, even the Advocate who would teach all truth, call to mind all that Jesus had said, and tell them what they were not yet strong enough to hear, would be acting in a "from" and "toward" mode. "Many things yet I have to say to you, but you cannot bear them now. But when he, the Spirit of truth has come, he will teach you all the truth. For he will not speak on his own authority, but whatever he will hear, he will speak, and the things that are to come he will declare to you" (John 16:12-13).

The first relatedness Jesus calls for is with him. This has great meaning for ecumenical efforts. "To John, being a Christian means being like the Son, becoming a son; that is, not standing on one's own and in oneself, but living completely open in the 'from' and 'toward'" (p. 187). The reflections on the Trinity have shown us "that Christian unity is first of all unity with Christ, which becomes possible where insistence on one's own individuality ceases and is replaced by pure unreserved being 'from' and 'for'" (p. 187).

The concluding sentence of the chapter on the Trinity sums up: "Just when we seem to have reaching the extreme limit of theory, the extreme of practicality comes into view: talking about God discloses what man is; the most paradoxical approach is at the same time the most illuminating and helpful one" (p. 190).

Richard of St. Victor

St. Bonaventure places Richard of St. Victor among the masters of contemplation. Dante salutes him as "in contemplation more than human." Little is known of his early life. He came perhaps from Scotland and entered the Abbey of St. Victor on the bank of the Seine outside the walls of Paris in the early 1150s. During the last decade and a half of his life he was first sub-prior and then prior of the monastery till his death in 1173.

His hope as prior to teach a solid mystical theology as the interior basis for good community relations provides reason enough for Richard's writing on the Trinity. Moreover, the Canons recited daily the Athanasian Creed, which is a detailed profession of faith in the Holy Trinity.

Richard's Book Three of the Trinity [2] is unique, however, in that it appeals to human reason to establish the necessity of three persons in God. The basis for this necessity is the perfection of love. Made in the image and likeness of God, a human being knows that love is necessary for happiness.

Through twenty-seven short chapters (pp. 371-397) Richard looks at every angle of the meaning of love and how it has to include relatedness. God could not be an absolutely alone person and be infinitely perfect, good, happy or powerful.

"Where there is fullness of all goodness, true and supreme charity cannot be lacking, for nothing is better than charity; nothing is more perfect than charity. However no one is properly said to have charity on the basis of his own private love for himself. And so it is necessary for love to be directed toward another for it to be charity. Therefore, where a plurality of persons is lacking, charity cannot exist." (p. 374)

After he has established that in God there must be a plurality, Richard of St. Victor goes on to say that the plurality must be more than two persons.

"It is necessary that each of those loved supremely and loving supremely should search with equal desire for someone who would be mutually loved and with equal concord willingly possess him. Thus you see how the perfection of charity requires a Trinity of persons, without which it is wholly unable to subsist in the integrity of its fullness. Thus, just as integral charity cannot be lacking, so also true Trinity cannot be lacking where everything that is, is altogether perfect. Therefore there is not only a duality but also true Trinity in true unity and true unity in true Trinity." (p. 385)

Richard a valuable guide

Richard of St. Victor was both an administrator and a teacher. He spoke often to the Canons in his monastery, preached to them and counseled them in private. Grover Zinn, the translator of Richard, sums up Richard's contribution in his work on the Trinity:

"In the supreme source of life, the Creator, one finds full personhood understood in terms of union and individuality; of loving, being loved and sharing love. Such a pattern suggests that in the imago Dei that is man, the reflection of this life should lead to a renewed appreciation of charity as a love lived in community with others, involving interpersonal sharing of the deepest kind." (p. 48)

It is not hard to see how meditation on the Trinity can strengthen the whole fabric of human relationships. It can help in the family, in a monastery or convent, in governmental bodies, in business, in any situation where cooperation is called for. You are most your true self, you are your best self, not when standing alone, but when aware of the primordial nature of relatedness in regard to unity. A true Christian, united with Christ, and aware from deep meditation that Christ and the Father are one, will be a person who strives humbly for unity. He knows that good human relatedness is a faint reflection of the relatedness that is essential in the divine unity.

The unique explorations of the two masters above, writing 800 years apart, arrive at the same conclusion. We might sum it up by saying that the nature of God includes a built-in relatedness. The medieval writer finds this result by examining the demands of perfect love, the modern writer by allowing his studies a double vantage point suggested by the demands of modern physics.

One simple, practical result from considering their thoughts about the Trinity, personhood and love, would be to make the Sign of the Cross in a thoughtful and deliberate manner. For priests this has application also in giving blessings, whether at the end of Mass or at other times. In this simple sign an amazing amount of mystery lies hidden. It deserves more perfection than an indefinite wave of the hand. (Perhaps a flashback to the idea of "parcels of waves" may help.) For it recalls at once the perfect sacrifice of Christ and the perfection of love that demands plurality in the Trinity.

ENDNOTES:

[1] Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, An Introduction to Christianity (English, 1990 & 2004, Ignatius Press, San Francisco).

[2] Richard of St. Victor, The Twelve Patriarchs, The Mystical Ark, Book Three of the Trinity (Paulist Press, New York, Ramsey, Toronto, 1979), pp. xvii & 425.

CLICK HERE to subscribe to Homiletic & Pastoral Review

Related IgnatiusInsight.com Articles and Excerpts:

• Are Truth, Faith, and Tolerance Compatible? | Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger

• Why Do We Need Faith? | Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger

• God's Eros Is Agape | Fr. James V. Schall, S.J.

• First Musings on Benedict XVI's First Encyclical | Fr. Joseph Fessio, S.J.

• Some Comments on Deus Caritas Est | Mark Brumley

• • Eternal Security? A Trinitarian Apologetic for Perseverance | Freddie Stewart, Jr.

• Jean Daniélou and the "Master-Key to Christian Theology" | Carl E. Olson

• Love Alone is Believable: Hans Urs von Balthasar's Apologetics | Fr. John R. Cihak

• Understanding The Hierarchy of Truths | Douglas Bushman, S.T.L.

Reverend Christopher Rengers, O.F.M. Cap., is in retirement at St. Augustine Friary in Pittsburgh, Penn. He continues to cooperate with the Workers of St. Joseph and the Queen of the Americas Guild in their endeavors to foster devotion to St. Joseph, Our Lady of Guadalupe and the Blessed Sacrament. His Marian books, Mary of the Americas and The Youngest Prophet, have been updated lately to include the canonization of St. Juan Diego and the beatification of Jacinta and Francisco of Fatima.

"The Trinity: Three Persons in One Nature" by Frank Sheed

The Trinity: Three Persons in One Nature | Frank Sheed | From Theology and Sanity | Ignatius Insight

The notion is unfortunately widespread that the mystery of the Blessed Trinity is a mystery of mathematics, that is to say, of how one can equal three. The plain Christian accepts the doctrine of the Trinity; the "advanced" Christian rejects it; but too often what is being accepted by the one and rejected by the other is that one equals three. The believer argues that God has said it, therefore it must be true; the rejecter argues it cannot be true, therefore God has not said it. A learned non-Catholic divine, being asked if he believed in the Trinity, answered, "I must confess that

the arithmetical aspect of the Deity does not greatly interest me"; and if the learned can think that there is some question of arithmetic involved, the ordinary person can hardly be expected to know any better.

the arithmetical aspect of the Deity does not greatly interest me"; and if the learned can think that there is some question of arithmetic involved, the ordinary person can hardly be expected to know any better. (i) Importance of the doctrine of the Trinity

Consider what happens when a believer in the doctrine is suddenly called upon to explain it — and note that unless he is forced to, he will not talk about it at all: there is no likelihood of his being so much in love with the principal doctrine of his Faith that he will want to tell people about it. Anyhow, here he is: he has been challenged, and must say something. The dialogue runs something like this:

Believer: "Well, you see, there are three persons in one nature."

Questioner: "Tell me more."

Believer: "Well, there is God the Father, God the Son, God the Holy Spirit."

Questioner: "Ah, I see, three gods."

Believer (shocked): "Oh, no! Only one God."

Questioner: "But you said three: you called the Father God, which is one; and you called the Son God, which makes two; and you called the Holy Spirit God, which makes three."

Here the dialogue form breaks down. From the believer's mouth there emerges what can only be called a soup of words, sentences that begin and do not end, words that change into something else halfway. This goes on for a longer or shorter time. But finally there comes something like: "Thus, you see, three is one and one is three." The questioner not unnaturally retorts that three is not one nor one three. Then comes the believer's great moment. With his eyes fairly gleaming he cries: "Ah, that is the mystery. You have to have faith."

Now it is true that the doctrine of the Blessed Trinity is a mystery, and that we can know it only by faith. But what we have just been hearing is not the mystery of the Trinity; it is not the mystery of anything, it is wretched nonsense. It may be heroic faith to believe it, like the man who

Wished there were four of 'em

That he might believe more of 'em

or it may be total intellectual unconcern - God has revealed certain things about Himself, we accept the fact that He has done so, but find in ourselves no particular inclination to follow it up. God has told us that He is three persons in one Divine nature, and we say "Quite so", and proceed to think of other matters - last week's Retreat or next week's Confession or Lent or Lourdes or the Church's social teaching or foreign missions. All these are vital things, but compared with God Himself, they are as nothing: and the Trinity is God Himself. These other things must be thought about, but to think about them exclusively and about the Trinity not at all is plain folly. And not only folly, but a kind of insensitiveness, almost a callousness, to the love of God. For the doctrine of the Trinity is the inner, the innermost, life of God, His profoundest secret. He did not have to reveal it to us. We could have been saved without knowing that ultimate truth. In the strictest sense it is His business, not ours. He revealed it to us because He loves men and so wants not only to be served by them but truly known. The revelation of the Trinity was in one sense an even more certain proof than Calvary that God loves mankind. To accept it politely and think no more of it is an insensitiveness beyond comprehension in those who quite certainly love God: as many certainly do who could give no better statement of the doctrine than the believer in the dialogue we have just been considering.

How did we reach this curious travesty of the supreme truth about God? The short statement of the doctrine is, as we have heard all our lives, that there are three persons in one nature. But if we attach no meaning to the wordperson, and no meaning to the word nature, then both the nouns have dropped out of our definition, and we are left only with the numbers three and one, and get along as best we can with these. Let us agree that there may be more in the mind of the believer than he manages to get said: but the things that do get said give a pretty strong impression that his notion of the Trinity is simply a travesty. It does him no positive harm provided he does not look at it too closely; but it sheds no light in his own soul: and his statement of it, when he is driven to make a statement, might very well extinguish such flickering as there may be in others. The Catholic whose faith is wavering might well have it blown out altogether by such an explanation of the Trinity as some fellow Catholic of stronger faith might feel moved to give: and no one coming fresh to the study of God would be much encouraged.

(ii) "Person" and "Nature"

Let us come now to a consideration of the doctrine of the Blessed Trinity to see what light there is in it for us, being utterly confident that had there been no light for us, God would not have revealed it to us. There would be a rather horrible note of mockery in telling us something of which we can make nothing. The doctrine may be set out in four statements:

In the one divine Nature, there are three Persons - the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.

The Father is not the Son, the Son is not the Holy Spirit, the Holy Spirit is not the Father: no one of the Persons is either of the others.

The Father is God, the Son is God, the Holy Spirit is God.

There are not three Gods but one God.

We have seen that the imagination cannot help here. Comparisons drawn from the material universe are a hindrance and no help. Once one has taken hold of this doctrine, it is natural enough to want to utter it in simile and metaphor - like the lovely lumen de lumine, light from light, with which the Nicene Creed phrases the relation of the Son to the Father. But this is for afterward, poetical statement of a truth known, not the way to its knowledge. For that, the intellect must go on alone. And for the intellect, the way into the mystery lies, as we have already suggested, in the meaning of the words "person" and "nature". There is no question of arithmetic involved. We are not saying three persons in one person, or three natures in one nature; we are saying three persons in one nature. There is not even the appearance of an arithmetical problem. It is for us to see what person is and what nature is, and then to consider what meaning there can be in a nature totally possessed by three distinct persons.

The newcomer to this sort of thinking must be prepared to work hard here. It is a decisive stage of our advance into theology to get some grasp of the meaning of nature and the meaning of person. Fortunately the first stage of our search goes easily enough. We begin with ourselves. Such a phrase as "my nature" suggests that there is a person, I, who possesses a nature. The person could not exist without his nature, but there is some distinction all the same; for it is the person who possesses the nature and not the other way round.

One distinction we see instantly. Nature answers the question what we are; person answers the question who we are. Every being has a nature; of every being we may properly ask, What is it? But not every being is a person: only rational beings are persons. We could not properly ask of a stone or a potato or an oyster, Who is it?

By our nature, then, we are what we are. It follows that by our nature we do what we do: for every being acts according to what it is. Applying this to ourselves, we come upon another distinction between person and nature. We find that there are many things, countless things, we can do. We can laugh and cry and walk and talk and sleep and think and love. All these and other things we can do because as human beings we have a nature which makes them possible. A snake could do only one of them - sleep. A stone could do none of them. Nature, then, is to be seen not only as what we are but as the source of what we can do.

But although my nature is the source of all my actions, although my nature decides what kind of operations are possible for me, it is not my nature that does them: I do them, I the person. Thus both person and nature may be considered sources of action, but in a different sense. The person is that which does the actions, the nature is that by virtue of which the actions are done, or, better, that from which the actions are drawn. We can express the distinction in all sorts of ways. We can say that it is our nature to do certain things, but that we do them. We can say that we operate in or according to ournature. In this light we see why the philosophers speak of a person as the center of attribution in a rational nature: whatever is done in a rational nature or suffered in a rational nature or any way experienced in a rational nature is done or suffered or experienced by the person whose nature it is.

Thus there is a reality in us by which we are what we are: and there is a reality in us by which we are who we are. But as to whether these are two really distinct realities, or two levels of one reality, or related in some other way, we cannot see deep enough into ourselves to know with any sureness. There is an obvious difference between beings of whom you can say onlywhat they are and the higher beings of whom you can say who they are as well. But in these latter - even in ourselves, of whom we have a great deal of experience - we see only darkly as to the distinction between the what and the who. Of our nature in its root reality we have only a shadowy notion, and of our self a notion more shadowy still. If someone - for want of something better to say - says: "Tell me about yourself", we can tell her the qualities we have or the things we have done; but of the self that has the qualities and has done the things, we cannot tell her anything. We cannot bring it under her gaze. Indeed we cannot easily or continuously bring it under our own. As we turn our mind inward to look at the thing we call "I", we know that there is something there, but we cannot get it into any focus: it does not submit to being looked at very closely. Both as to the nature that we ourselves have and the person that we ourselves are, we are more in darkness than in light. But at least we have certain things clear: nature says what we are, person says who we are. Nature is the source of our operations, person does them.

Now at first sight it might seem that this examination of the meaning of person and nature has not got us far toward an understanding of the Blessed Trinity. For although we have been led to see a distinction between person and nature in us, it seems clearer than ever that one nature can be possessed and operated in only by one person. By a tremendous stretch, we can just barely glimpse the possibility of one person having more than one nature, opening up to him more than one field of operation. But the intellect feels baffled at the reverse concept of one nature being totally "wielded", much less totally possessed, by more than one person. Now to admit ourselves baffled by the notion of three persons in the one nature of God is an entirely honorable admission of our own limitation; but to argue that because in man the relation of one nature to one person is invariable, therefore the same must be the relation in God, is a defect in our thinking. It is indeed an example of that anthropomorphism, the tendency to make God in the image of man, which we have already seen hurled in accusation at the Christian belief in God.

Let us look more closely at this idea. Man is made in the image and likeness of God. Therefore it is certain that man resembles God. Yet we can never argue with certainty from an image to the original of the image: we can never be sure that because the image is thus and so, therefore the original must be thus and so. A statue may be an extremely good statue of a man. But we could not argue that the man must be a very rigidman, because the statue is very rigid. The statue is rigid, not because the man is rigid, but because stone is rigid. So also with any quality you may observe in an image: the question arises whether that quality is there because the original was like that or because the material of which the image is made is like that. So with man and God. When we learn anything about man, the question always arises whether man is like that because God is like that, or because that is the best that can be done in reproducing the likeness of God in a being created of nothing. Put quite simply, we have always to allow for the necessary scaling down of the infinite in its finite likeness.

Apply this to the question of one person and one nature, which we find in man. Is this relation of one-to-one the result of something in the nature of being, or simply of something in the nature of finite being? With all the light we can get on the meaning of person and of nature even in ourselves, we have seen that there is still much that is dark to us: both concepts plunge away to a depth where the eye cannot follow them. Even of our own finite natures, it would be rash to affirm that the only possible relation is one person to one nature. But of an infinite nature, we have no experience at all. If God tells us that His own infinite nature is totally possessed by three persons, we can have no grounds for doubting the statement, although we may find it almost immeasurably difficult to make any meaning of it. There is no difficulty in accepting it as true, given our own inexperience of what it is to have an infinite nature and God's statement on the subject; there is not difficulty, I say, in accepting it as true; the difficulty lies in seeing what it means. Yet short of seeing some meaning in it, there is no point in having it revealed to us; indeed, a revelation that is only darkness is a kind of contradiction in terms.

(iii) Three Persons - One God

Let us then see what meaning, - that is to say, what light, - we can get from what has been said so far. The one infinite nature is totally possessed by three distinct persons. Here we must be quite accurate: the three persons are distinct, but not separate; and they do not share the divine nature, but each possesses it totally.

At this first beginning of our exploration of the supreme truth about God, it is worth pausing a moment to consider the virtue of accuracy. There is a feeling that it is a very suitable virtue for mathematicians and scientists, but cramping if applied to operations more specifically human. The young tend to despise it as a kind of tidiness, a virtue proper only to the poor-spirited. And everybody feels that it limits the free soul. It is in particular disrepute as applied to religion, where it is seen as a sort of anxious weighing and measuring that is fatal to the impetuous rush of the spirit. But in fact, accuracy is in every field the key to beauty: beauty has no greater enemy than rough approximation. Had Cleopatra's nose been shorter, says Pascal, the face of the Roman Empire and so of the world would have been changed: an eighth of an inch is not a lot: a lover, you would think, would not bother with such close calculation; but her nose was for her lovers the precise length for beauty: a slight inaccuracy would have spoiled everything. It is so in music, it is so in everything: beauty and accuracy run together, and where accuracy does not run, beauty limps.

Returning to the point at which this digression started: we must not say three separate persons, but three distinct persons, because although they are distinct - that is to say, no one of them is either of the others - yet they cannot be separated, for each is what he is by the total possession of the one same nature: apart from that one same nature, no one of the three persons could exist at all. And we must not use any phrase which suggests that the three persons share the Divine Nature. For we have seen that in the Infinite there is utter simplicity, there are no parts, therefore no possibility of sharing. The infinite Divine Nature can be possessed only in its totality. In the words of the Fourth Council of the Lateran, "There are three persons indeed, but one utterly simple substance, essence, or nature."

Summarizing thus far, we may state the doctrine in this way: the Father possesses the whole nature of God as His Own, the Son possesses the whole nature of God as His Own, the Holy Spirit possesses the whole nature of God as His Own. Thus, since the nature of any being decides what the being is, each person is God, wholly and therefore equally with the others. Further, the nature decides what the person can do: therefore, each of the three persons who thus totally possess the Divine Nature can do all the things that go with being God.

All this we find in the Preface for the Mass on the Feast of the Holy Trinity: "Father, all-powerful and ever-living God, ... we joyfully proclaim our faith in the mystery of your Godhead ...: three Persons equal in majesty, undivided in splendor, yet one Lord, one God, ever to be adored in your everlasting glory."

To complete this first stage of our inquiry, let us return to the question which, in our model dialogue above, produced so much incoherence from the believer - if each of the three persons is wholly God, why not three Gods? The reason why we cannot say three Gods becomes clear if we consider what is meant by the parallel phrase, "three men". That would mean three distinct persons, each possessing a human nature. But note that, although their natures would be similar, each would have his own. The first man could not think with the second man's intellect, but only with his own; the second man could not love with the third's will, but only with his own. The phrase "three men" would mean three distinct persons, each with his own separate human nature, his own separate equipment as man; the phrase "three gods" would mean three distinct persons, each with his own separate Divine Nature, his own separate equipment as God. But in the Blessed Trinity, that is not so. The three Persons are God, not by the possession of equal and similar natures, but by the possession of one single nature; they do in fact, what our three men could not do, know with the same intellect and love with the same will. They are three Persons, but they are not three Gods; they are One God.

Related Ignatius Insight Book Excerpts:

• The Incarnation | Frank Sheed

• The Problem of Life's Purpose | Frank Sheed

• The Trinity and the Nature of Love | Fr. Christopher Rengers

• The Creed and the Trinity | Henri de Lubac

• • The Ministry of the Bishop in Relation to the Blessed Trinity | Cardinal Francis George, O.M.I

• The Reality of God": Benedict XVI on the Trinity | Fr. James V. Schall, S.J.

• Eternal Security? A Trinitarian Apologetic for Perseverance | Freddie Stewart, Jr.

• Jean Daniélou and the "Master-Key to Christian Theology" | Carl E. Olson

• God's Eros Is Agape | Fr. James V. Schall, S.J.

• First Musings on Benedict XVI's First Encyclical | Fr. Joseph Fessio, S.J.

• Some Comments on Deus Caritas Est | Mark Brumley

• Love Alone is Believable: Hans Urs von Balthasar's Apologetics | Fr. John R. Cihak

• Understanding The Hierarchy of Truths | Douglas Bushman, S.T.L.

Frank Sheed (1897-1981) was an Australian of Irish descent. A law student, he graduated from Sydney University in Arts and Law, then moved in 1926, with his wife Maisie Ward, to London. There they founded the well-known Catholic publishing house of Sheed & Ward in 1926, which published some of the finest Catholic literature of the first half of the twentieth century.

Frank Sheed (1897-1981) was an Australian of Irish descent. A law student, he graduated from Sydney University in Arts and Law, then moved in 1926, with his wife Maisie Ward, to London. There they founded the well-known Catholic publishing house of Sheed & Ward in 1926, which published some of the finest Catholic literature of the first half of the twentieth century.Known for his sharp mind and clarity of expression, Sheed became one of the most famous Catholic apologists of the century. He was an outstanding street-corner speaker who popularized the Catholic Evidence Guild in both England and America (where he later resided). In 1957 he received a doctorate of Sacred Theology honoris causa authorized by the Sacred Congregation of Seminaries and Universities in Rome.

Although he was a cradle Catholic, Sheed was a central figure in what he called the "Catholic Intellectual Revival," an influential and loosely knit group of converts to the Catholic Faith, including authors such as G.K. Chesterton, Evelyn Waugh, Arnold Lunn, and Ronald Knox.

Sheed wrote several books, the best known being Theology and Sanity, A Map of Life, Theology for Beginners and To Know Christ Jesus. He and Maise also compiled the Catholic Evidence Training Outlines, which included his notes for training outdoor speakers and apologists and is still a valuable tool for Catholic apologists and catechists (and is available through the Catholic Evidence Guild).

For more about Sheed, visit his IgnatiusInsight.com Author Page.

May 25, 2013

The Trinity: A Mystery for Eternity

A Scriptural Reflection on the Readings for Sunday, May 26, 2013, The Solemnity of the Most Holy Trinity

Readings:

• Prov 8:22-31

• Ps 8:4-5, 6-7, 8-9

• Rom 5:1-5

• Jn 16:12-15

The apologist and novelist Dorothy Sayers dryly noted, in an essay

titled “The Dogma is the Drama,” that for many people, even some Christians,

the doctrine of the Trinity is, “The Father incomprehensible, the Son

incomprehensible, and the whole thing incomprehensible.” There are likely a few

Catholics who would candidly admit, “Well, the Church teaches that the Trinity

is a mystery—and it’s certainly a mystery to me!”

In fact, the Catechism of the

Catholic Church explains, “The mystery of

the Most Holy Trinity is the central mystery of Christian faith and life” (CCC

234). It goes on to explain that this great mystery is the most fundamental,

essential teaching in the “hierarchy of the truths of faith” and that it is a

mystery of faith “in the strict sense”—it cannot be known except it has been

revealed by God (CCC 237). A theological mystery such as the Trinity is a truth

about God known only through divine revelation, not by reason or philosophy. It

is like a well with no bottom from which we can drink endlessly, our minds and

souls never going away thirsty.

Belief in the Trinity—one God who

is Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—is a distinctive mark of the Christian Faith. The

first few centuries of the Church were filled with controversies and careful

definitions regarding the one nature of God, the three Persons of the Trinity,

and their relationship with each other. Yet the dogma of the Trinity cannot be

proven in the usual sense of “proven” and “proof.” But this does not mean that

the dogma of the Trinity is contrary to reason or that reason cannot be applied

to understanding it to some degree (cf. CCC 154); it means that the Triune

reality of God is ultimately beyond human reasoning. As St. Augustine remarked,

“If you understood Him, it would not be God” (CCC 230).

Today’s readings do not use the term “Trinity,” of course,

because it doesn’t appear in Scripture. But they are some of the many texts the

Church has looked to as either foreshadowing the reality of the Trinity or

giving explicit witness to it. The

reading from Proverbs is one of several Old Testament passages that describe

the wisdom of God, which is often referred to as a sort of personal being or

reality. Some of this language is taken up in the New Testament to refer to the

Son, including St. Paul’s description of Christ as “the power of God and the

wisdom of God” (1 Cor 1:24). Or, similarly, in a passage that bears a strong

resemblance to today’s reading from Proverbs, the “one Lord, Jesus Christ” is

described as the one “through whom all things are and through whom we exist” (1

Cor 8:6).

While the Old Testament contains hints and suggestions, the

mystery of the Trinity was revealed with the Incarnation—first at Jesus’

baptism in the Jordan River, and then in His teachings. Jesus spoke of the

intimate communion between the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, including in

today’s reading from the Gospel of John. “Everything that the Father has is

mine,” Jesus tells the Apostles, “for this reason I told you that he”—the Holy

Spirit—“will taken from what is mine and declare it to you.” The Father sends

forth the Son so that, as St. Paul wrote to the Romans, we might have peace

with God, while the Holy Spirit pours out God’s love, all so we might be

justified and made right with God.

In his great work The Trinity, St. Augustine summed up the heart of the Church’s belief in the

mystery of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit by simply stating, “If you see

charity, you see the Trinity.” God is One and three Persons; He offers His divine life and love to

those who believe in Him (CCC 257). The Trinity is not just a mystery to us,

but also for us.

(This "Opening the Word" column originally appeared in the June 3, 2007, issue of Our Sunday Visitor newspaper.)

May 23, 2013

Former atheist: "Ignatius Press is my publisher!!!!"

Prolific blogger and former atheist Jennifer Fulwiler posted this news yesterday on her Conversion Diary blog:

One thousand eight hundred and twenty days ago, I started writing my book, a memoir about going from atheism to belief. After three complete, from-a-blank-page rewrites; countless feedback sessions from Joe and my agent and brilliant fellow writers, each of which left me wondering whether I should perhaps just give up on the written word altogether; revisions that made me feel like my brain was melting; a reality show;

three new babies; and a pitch process that almost sent me into cardiac

arrest every time I saw my agent’s name in my inbox…I finally have a

publisher.

I know I use this word too much, but there is no other way to

describe the pitch process other than to say it was EPIC. When Ted, my

agent, first told me that we had multiple offers from great publishers, I

was thrilled. My excitement quickly melted into a vague sense of dread,

however, when I realized that I could only pick one. I know, I know,

good problem to have. But because my writer angst knows no bounds, I had

these visions of making the wrong decision and ruining everyone’s life

in the process, leaving some poor acquisitions editor so scarred that

she’d spit on the ground any time she heard my name.

I prayed for direction, and to my great relief my prayers were

answered. God made it clear which house would be the right fit for this

project, probably because he knew that I’d turn this situation into too

much of a hot mess if he didn’t intervene directly this time. Ted made

some calls, we all signed some papers, and now I can finally tell you:

Ignatius Press is my publisher, and my book will probably be released either this Fall or next Spring! ...

I keep waiting for Mark Brumley to call and tell me delicately that

there’s this professor with five PhDs named Jennifer Fullwider, and,

long story short, a horrible mistake has been made. But that hasn’t

happened yet, and I’ve given it a few weeks, so I guess I can officially

say:

Ignatius Press is my publisher!!!!

Congratulations to Jennifer on this good news!

Pope Francis teaches that everyone is saved! Wow! (Hold on. Wait a second.)

by Carl E. Olson | CWR blog

By now you've heard about the Pope's astounding remark about the redemption of all men:

In the Holy Spirit, every individual and all people have become, through the Cross and Resurrection of Christ, children of God, partakers in the divine nature and heirs to eternal life. All are redeemed and called to share in glory in Jesus Christ, without any distinction of language, race, nation or culture. The Good News which Christ proclaimed and which the Church continues to proclaim, in accordance with the Lord's will, must be preached "to all creation" and "to the ends of the earth".

Oops, sorry—that was actually Pope John Paul II, back in 1981 in Manila. Let's see. Hold on a second. Try this:

God our Savior…desires all men to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth. For there is one God, and there is one mediator between God and men, the man Christ Jesus, who gave himself as a ransom for all, the testimony to which was borne at the proper time. … For the grace of God has appeared for the salvation of all men.

Whoops! That's the Apostle Paul, writing a couple of thousand years ago to Timothy and Titus (1 Tim 2:3-6; Tit 2:11). My apologies. Here goes:

But, if Christian precepts prevail, the respective classes will not only be united in the bonds of friendship, but also in those of brotherly love. For they will understand and feel that all men are children of the same common Father, who is God; that all have alike the same last end, which is God Himself, who alone can make either men or angels absolutely and perfectly happy; that each and all are redeemed and made sons of God, by Jesus Christ, "the first-born among many brethren"; that the blessings of nature and the gifts of grace belong to the whole human race in common, and that from none except the unworthy is withheld the inheritance of the kingdom of Heaven. "If sons, heirs also; heirs indeed of God, and co-heirs with Christ."

No, no, no. Wrong pope! That was Pope Leo XIII, back in 1891. How embarrassing that I cannot get my quotes right. I'm doing my best, I really am.

By his glorious Cross Christ has won salvation for all men. He redeemed them from the sin that held them in bondage. … Created in the image of the one God and equally endowed with rational souls, all men have the same nature and the same origin. Redeemed by the sacrifice of Christ, all are called to participate in the same divine beatitude: all therefore enjoy an equal dignity.

You're onto me: that was the Catechism of the Catholic Church (pars 1741, 1934). Ummm. Try this one:

May 22, 2013

How Great is This Gatsby?

How Great is This Gatsby? | Thomas M. Doran | Catholic World Report

A review of Baz Luhrmann’s new film adaptation of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby

Ad Finem Fidelis…faithful to the

end. Well, not exactly. These words are inscribed on Gatsby’s mansion gate and are

laden with irony in relation to this film.

When a film is made of a great

book, I am willing to tolerate a fair amount of artistic license, character

elimination, and innovation, but messing with the principal themes of the book

is verboten. To Kill a Mockingbird

lost some characters and some scenes, and The

Lord of the Rings took some liberties with the plot, but I consider these

films to be faithful to the main themes of the Lee and Tolkien stories.

We have become so inured to

action, glitz, and sensory assault that making a big budget film without a

healthy dose of sensory stimuli is

practically unthinkable. When such directorial innovations are confined to,

say, a sledding Radagast the Brown in The

Hobbit, I groan and move on, but I draw the line when stimulation defines

the film, as it does with this new Gatsby,

especially as F. Scott Fitzgerald’s story has so much to offer.

Having said this, there are aspects

of this film that are appealing and compelling, so stay tuned.

Everyone who has read The Great Gatsby, or who has seen

earlier films, knows about the title character’s obsession with Daisy, and the

way this obsession has changed, even defined, his life.

So far, so good. There’s a lot

more to the story than this.

Thinking as a Christian with Josef Pieper

Thinking as a Christian with Josef Pieper | Matthew Anger | HPR

In an age when society is again becoming highly polarized, it is important to remember that the lack of real communication causes a breakdown in civility, and an increase in ignorance.

During his long lifetime, Josef Pieper (1904-1997) was known as a leading member of the neo-Thomist movement. When his most famous work, Leisure: The Basis of Culture (1952), appeared in English, a reviewer at the Chicago Tribune wrote: “Pieper has subjects involved in everyone’s life; he has theses that are so counter to the prevailing trends as to be sensational; and he has a style that is memorably clear and direct.” The German philosopher can be easily ranked alongside Jacques Maritain and Etienne Gilson as one of the important Catholic thinkers of the postwar period. He made the theories of high academia approachable to the educated layman, and for many decades Pieper’s works were widely disseminated by both mainstream and religious institutions. Fortunately, many of them remain in print.

The first thing to note is Pieper’s unique style. Anyone sampling his writing will find it highly economical: there is no wasted thought or verbiage. Few of his books—most of which are long essays—are more than a hundred pages in length, and many are even shorter. But one should not be misled by his brevity. Within each of these studies is a mass of highly condensed thought and weighty considerations which span the millennia, from the pre-Socratic Greeks to the insights of 20th century intellects. Some of his works can be read in an hour or two. But they are studies that can last a lifetime.

The second consideration for the reader is the author’s highly integrated and harmonized outlook. There are many recurring themes—for example, his views on the meaning of philosophical dialogue, the idea of the incarnated soul, or the human capacity for leisure. For this reason, I will not approach his thought in terms of individual titles, which would result in a somewhat tedious and confusing list of books. Instead, I will treat each major theme systematically, and provide a bibliography for readers who want to pursue his major writings further.

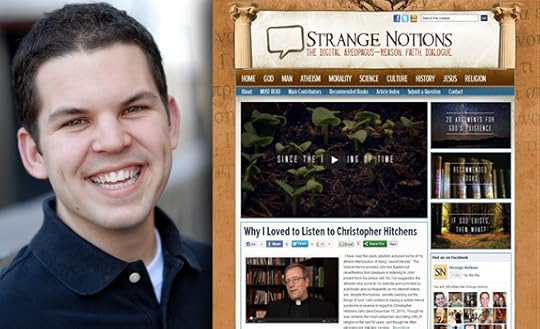

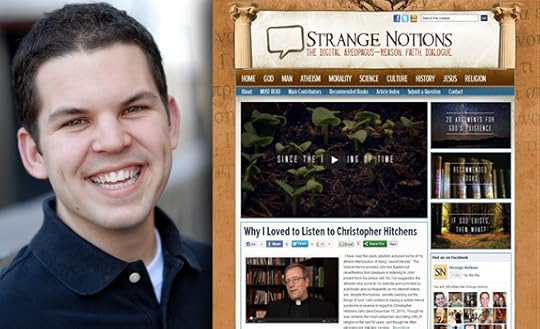

Catholics, Atheists, and the “Digital Areopagus”

Catholics, Atheists, and the “Digital Areopagus” | CWR Staff | Catholic World Report

An interview with author and blogger Brandon Vogt about

StrangeNotions.com

Brandon Vogt apparently does not sleep very much. He is an

author, blogger, and speaker, as well as an engineer, husband, and father. His

first book was titled The Church and New Media: Blogging Converts, Online

Activists, and Bishops Who Tweet (Our

Sunday Visitor, 2011), and included a Foreword by Cardinal Sean O'Malley and an

Afterword by Cardinal Timothy Dolan.

Brandon’s most recent project is the site, StrangeNotions.com, which is “designed

to be the central place of dialogue online between Catholics and atheists. Its

implicit goal is to bring non-Catholics to faith--especially followers of the

so-called New Atheism. As a 'digital Areopagus', the site will include

intelligent articles, compelling video, and rich discussion through its comment

boxes.” It is, Brandon says, “the first English apostolate dedicated solely to

reaching atheists and agnostics.” He recently answered some questions put to

him by Catholic World Report.

CWR: There are countless Catholic websites, many of them

dedicated to apologetics and evangelization. What is unique about

StrangeNotions.com?

Brandon Vogt: Well, first the

aim. Few other sites exclusively engage atheists. Most focus on Protestant

apologetics, which is certainly needed, but the issues there are quite

different than those relevant to non-believers. For example, at Strange Notions

we don't really focus on Marian dogmas, purgatory, or the liturgy. We're

concerned with more basic questions about God's existence, cosmology, morality,

miracles, science, and the reliability of the Gospels. We must solidify these

foundational issues before the second-level issues become important.

Second, the tone. We're all familiar with the typical online religious

discussion. If not, just visit any secular newspaper site and scroll down to

the comments. They're full of snark, shallowness, and slander. But Strange Notions

is not like that. We've done several things to ensure the dialogue remains

serious and charitable, and in the site's first weeks it seems to have

worked. Our tight comment policy and several moderators have kept the

discussions fair and on point.

Third, the contributors really differentiate this site from

others. I've gathered the best-of-the-best Catholic intellects to

contribute content including Dr. Peter Kreeft, Dr. Edward

Feser, Fr. Robert Barron, Fr. Robert Spitzer, Dr. Benjamin

Wiker, Dr. Christopher Kaczor, Dr. Janet Smith, Dr. Kevin Vost,

Christopher West, Jimmy

Akin, Jennifer Fulwiler, Marc Barnes, Leah Libresco, Stacy Trascanos,

Mark Shea, Tim Staples, Carl Olson, and many more. Right now we have

over thirty contributors and we're continuing to add more. The hope

is that this website becomes the definitive Catholic response to atheism--the

best of our rich theological and philosophical tradition.

Finally, we have some exciting plans in the works to set the site apart,

including interactive YouTube debates and video interviews with popular

atheists and Catholics. So stay tuned!

CWR: Why the specific focus on atheism?

Continue reading on the CWR blog.

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers