Gaston Dorren's Blog

September 18, 2024

Upcoming talk

Live in or near London, England? Watch this video!

May 26, 2024

Twenglish

In quite a few languages, the word for ‘twenty’ is derived from a word meaning ‘person’ or ‘body’. The logic runs like this: 5 is ‘a hand’, 10 is ‘two hands’, 15 is ‘both hands and a foot’, and 20 is ‘all hands and feet’ – in other words, all the digits of our bodies.

Also in quite a few languages, the word used to designate both the language itself and its speakers literally means ‘person’ or ‘people’ or ‘real people’. The Yami of Taiwan, for instance, call themselves Tao or ‘people’, and their language ciriciring no tao, ‘speech of people’.

If a significant number of languages use ‘person’ for ‘twenty’ and ‘persons’ or ‘people’ for the language itself and its speakers, it stands to reason that some of them call themselves something like ‘twenty’. And so they do. I happened upon three of them in the span of just a few days.

The neatest case is found on the Philippine island of Luzon: in Arta, one word for ‘20’ is arta. (There’s another one that translates simply as ‘two tens’, not unlike our ‘twenty’.) The Arta language is falling out of use today, and earlier this century, there must have been a moment when there were exactly 20 Arta speakers left. It would be funny if it weren’t tragic.

In the Indonesian part of New Guinea, there’s a people and a language called Aghu. Their word for ‘twenty’ is aghu-bigi, where bigi means ‘full-length, complete’.

And then there’s Iñupiaq, spoken in Alaska. Iñuk (plural: iñuit) means ‘person’, while piaq means ‘real’. And what’s the word for ‘twenty’? Iñuiññaq. The –ñaq part, again, stands for ‘complete’.

Theoretically, the speakers of Arta, Aghu and Iñupiaq might call the year 2024 ‘person-person-four’. I’m pretty sure they don’t, but it tickles me just to think that they could.

April 10, 2024

‘Corncob-iron.’ Say what?

A ‘snake-iron’ is a train. I get that. And a ‘vulture-iron’ is a plane. Beautiful. Both words are used in Q’eqchi’, a Mayan language spoken in Guatemala and Belize. Or to be completely accurate, these are the literal bit-by-bit translations of the actual Q’eqchi’ words.

Q’eqchi’ has several other such words for metal objects. ‘Awakening iron’ for alarm clock. Not quite as interesting. ‘Thorn-iron’ for fork or rake. Nice. ‘Transporter-iron’ for car. Um – boring.

And then there’s one that I simply don’t understand. There must be some logic to it, but I can’t see it. I’m talking about the Q’eqchi’ word for bicycle, b’aqlay ch’iich’, which bit-by-bit translates as ‘corncob-iron’. Why the corncob? Why should a bicycle remind the Q’eqchi’-speakers of a metal corncob?

AI, ever the confident fool, has an interpretation ready (see picture), but I, without the A, do not. I remain deeply puzzled. If you have an inkling, and a heart, please share your thoughts down below.

January 19, 2024

Butter No Parsnips

I think of myself as a language and linguistics writer, not a polyglot. But nor am I ashamed of speaking a few languages – imperfectly, but serviceably. So when the people of the Butter No Parsnips podcast invited me for an interview, I agreed. The result’s just come out. You can hear it on Spotify or Apple Podcasts or Player FM and Web knows where else. The thing here below is just the trailer.

January 18, 2024

Making a case in three simple steps

Latin has them, Russian has them, and even English has conserved a tiny trace of them. I’m speaking of case endings, those grammatical boobytraps that make second-language speakers hesitant to finish their words. In Latin it’s rosa, rosae and the rest, in Russian it’s the thing that made me give up studying the language and in English it’s the difference between greengrocer and greengrocer’s.

Cases, however annoying, aren’t useless, but nor are they indispensable, and lots of languages do without them. So why haven’t Latin and Russian done away with them? Sorry to correct you, but Latin has: see Spanish, French and the other daughters. With Russian and most other Slavics, the answer is filial piety. Children, even teenagers, even rebellious teenagers, speak largely the way their parents taught them to.

The more interesting question really is: how did cases come about?

In general terms, endings are often former words clinging on for dear life. A clear example is the regular English past tense ending: the –ed of forms like I baked are the remains of an old Germanic word, *dedē, which has also given us did. So baked can be thought of as bake-did. (Probably, anyway. No surviving witnesses.)

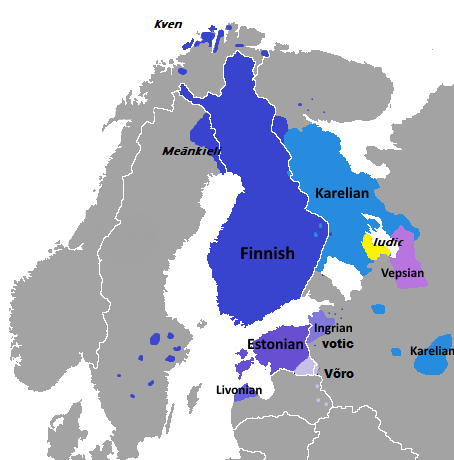

How about cases? Frankly, I don’t know about the origin of the Latin and Russian cases, nor English’s pathetic one single specimen. But I’ve just come across a beautiful example of how ome particular case came about in Karelian. You know – Karelian? Spoken in Karelia? Karelia, like the UK, is a region bordering on the EU. It’s the part of Russia that borders on Finland, is Karelia. Its language is a close relative of Finnish.

It’s like this. In the deep past, say 25 centuries ago, there was neither Finnish nor Karelian, only a language now known to linguists as Balto-Finnic. In Balto-Finnic there was a word kanssa meaning ‘people’. In modern Finnish, it still exists, but it now means ‘with’. One can see why: people are company, and ‘with’ expresses who the company consists of. (In French, an old word for ‘house’ now means ‘at’, as in ‘at my parents’ [house]’. That’s how prepositions come about.) Ah, and the Finns place their prepositions behind their nouns, that’s also important to know. They’re not so much pre- as post-positions. They don’t say ‘with the rebellious child’ but ‘the rebellious child with’. And they don’t have articles, so: ‘rebellious child with’.

Okay, so in Finnish, a noun has become a postposition. Next, there’s another offshoot of Balto-Finnic called Vepsian, spoken a short way (250 verst or so) east of Saint Petersburg. Here, the old word kanssa has been reduced to ka. Also, the postposition has changed to a suffix, meaning that it is no longer a word, but an ending. We have already seen both changes in our English example: the old word dedē got reduced to ed and became an ending, -ed: you can’t cut baked in two and shove something in between. Same with -ka in Vepsian. So if Finnish has ‘rebellious child with’, Vepsian has ‘rebellious childwith’, or perhaps I should write ‘rebellious childwi’.

And then there is, as promised, Karelian. Here, the form has become –kela – don’t ask me where the additional letters come from, I don’t know; the experts are confident that the whole thing has the same origin. As in Vepsian, this -kela is stuck at the end of the word. But something new has happened: while it still means ‘with’, it now gets attached to both the noun AND the adjective. ‘With the rebellious child’ in Karelian is something like ‘rebelliouswil childwil’ (where -wil is my silly way of rendering –kela in English). Which is very similar to what you would see in Latin or Russian. Not literally of course, but structurally: -kela is a case ending.

So there you have it: from noun to case in three simple steps. If you want to know more about these sorts of processes: I read it in Peter Trudgill’s book Millennia of Language Change. Trudgill is a lively writer, so if you’re madly into language and can handle a fair amount of linguistic jargon, I recommend it. His source, in turn, was Lynne Campbell’s article On the linguistic prehistory of Finno-Ugric. That sounds like a plodding read, but I could be wrong.

July 14, 2023

Capital mistake

A Cypriot reader of Babel drew my attention to what he considered ‘a big mistake’ in the Greek translation: my claim that Turkish is spoken in Northern Cyprus. ‘There is not a country named North Cyprus,’ he countered. ‘The northern part of the island is occupied and only recognised by the occupiers (Turkey).’

That’s true in my world as well. At the same time, it’s also a fact that most people in that unrecognised country speak Turkish. So where’s the big mistake? Could this be just another case of fact-free nationalism?

I was in the process of writing a puzzled reply when a possible explanation dawned on me, and checking the English and Greek editions of the book seemed to corroborate it. At first sight, the translation was immaculate: Northern Cyprus, Vóreios Kúpros. However, while words like Northern and Western are often written with a capital in English, Greek only seems to do so when they’re part of an established name. If the translator had written vóreios Kúpros, this simply would have meant ‘Northern Cyprus’, as in ‘the Northern part of the island called Cyprus.’ However, she committed the infelicity of using a capital V, Vóreios Kúpros, which placed this entity in the same category as Vóreia Koréa and Vóreia Makedonía—countries. Hence the reader’s protest.

Before I could even finish this short blogpost, my correspondent replied to confirm that that was exactly it. He was going to notify the publisher in Athens, he announced.

March 24, 2023

After John, after jam

When you’re learning a new language, prepositions seem nice and easy at first. But after a while they prove to be pesky little buggers, keen on causing mischief. That’s certainly true for Polish, currently my favourite nuisance. One of its mischievous prepositions is po, followed by the locative case. Its most frequent meaning is ‘after’ – but what an ‘after’ it is sometimes!

In English, John’s wife becomes John’s widow after John’s death. Not so in Polish. Here, after John’s death, John’s wife becomes the ‘widow after John’: wdowa po Janie. One sees the logic: post-John, she’s a widow. But ‘widow after John’ would most definitely raise a lot of eyebrows in English. And not only in English: I don’t know of any Germanic or Romance language where a widow is said to be ‘after’ her dead spouse. Nor a widower – let’s not forget the bereft men.

It doesn’t take dying. Much less tragic events have the same effect of creating an aftertime, so to speak. Eating jam will do. Drinking beer will do. Even unboxing a pair of shoes is enough. I’ll explain.

A Polish ‘jar of jam’, filled with the sweet stuff, is very similar to an English one: słoik dżemu, in which słoik is a jar, dżem is how Polish spells ‘jam’ and the u-ending means ‘of’. But a ‘jam jar’ is a different matter. A jam jar no longer contains jam, it’s beyond jam – it’s after its jam phase. So there’s po again: słoik po dżemie, ‘jar after jam’. The same with beer bottles and shoe boxes: they’re ‘bottles after beer’ and ‘boxes after shoes’. (Just so you can verify: Butelki po piwie, pudełka po butach.) These are just examples, of course.

What I don’t know is how Poles call jars, bottles and boxes that are waiting to be filled with jam, beer and shoes. Jars for jam – słoiki na dżem? Of perhaps they follow the deep-rooted Slavic tendency to create special adjectives: jammy jars – słoiki dżemowe? My impression is that both constructions are not exactly wrong, but neither are they standard. I’m happy to bow to superior wisdom though. And I’m well aware that over 40 million people have such wisdom.

I’m also not sure how far this ‘after’ logic can be stretched. For instance, you’ve nearly reached the end of this blogpost. Does that make you a ‘reader after blog’ (czytelnik po blogu)? Makes sense to me. Not to the Poles, alas.

September 14, 2022

Let me mnow your mnemonics!

To memorise new words in foreign languages, I use all kinds of tricks. I look for etymological relationships to more words I know, I stick Post-its to objects, I listen to songs that have the word in their chorus. But my number two favourite (etymology is number one) is the kind of mnemonic device known as ‘bridge for donkeys’ in German and Dutch: an artificial and often tenuous, but helpful connexion between the hard word and something familiar.

I’ll list some examples here, mostly in order to inspire you to remember your own mnemonics and share them with me. How have you memorised those hard words in French, Spanish, German, Russian, Mandarin or indeed English, if that’s your second language?

Most of the list is from Polish, since that’s what I’m currently learning. I used to have lots of mnemonics for French, Spanish, Vietnamese and English as well, but I no longer need them. They’re like scaffolding: once the house has been built, you no longer need it. Though in the case of my personal history with Vietnamese, a more apt metaphor would be: once the unfinished house has been abandoned, it will collapse, the scaffolding along with it.

Gasić means ‘to extinguish’. My mnemonic is ‘turn off the gas’. Fortunately, I had less trouble memorising ‘turn on, to ignite’, so no confusion there.Badać means ‘to research, to explore’. Somehow I kept inverting the first two consonants (*dabać), until I realised that researchers and explorers can be real badasses (in the best possible meaning of the word, of course). That took care of it.How to memorise marzyć, meaning ‘to dream, to wish’? In winter, I dream of March, typically the first clement month here in the Netherlands, which in Polish is called marzec . Nearly all Polish verbs end in ć, not c, so the difference between marzyć and marzec is only this one vowel, really.Pielęgnować means ‘to nurse’. Piel is Spanish for ‘skin’, e.g. the skin of the leg – which is the next syllable. Nurses will care for the skin of the leg, e.g. when it’s burnt. Far-fetched? Absolutely! But if it works, it works. Can’t deny I prefer simpler ones though, such as the next.Puppis is Latin for the ‘stern’ of a ship. In English, this can also be called the ship’s poop, though I can’t imagine any kid saying that without a giggle. Dutch also has the woord poop (spelled poep) in the meaning of ‘fecal matter’. And where does poep come from? From our bodies’ very own sterns. Again, problem solved! Not in the best of taste, I guess, but as a 13-year old student, I found it helpful. And truth be told, even today I sometimes use mnemonics I would blush to share, including for some personal names.So these were some of mine. What are yours like? I’m really keen to know, so I hope you’ll share them in the comments or on social media. They may even end up in a book I’m working on. These ‘bridges for donkeys’ that you use may be visual, auditive or based on one of the other senses. They can be far-fetched or in dubious taste. I don’t care, as long as you can explain why each of them works for you.

Bring them on!

July 8, 2022

What does a language writer do?

Screenwriters write for the screen, ghostwriters write like (invisible) ghosts and sports writers write about sports. As a language writer, I write in language about language. Or rather: in languages (English and Dutch) about languages (dozens of ’em).

From history and politics to spelling, vocabulary and grammar: no matter how mundane or arcane the linguistic issue, I will deal with it in a way that both enlightens and entertains you – or so readers and reviewers across Europe, North America and Asia persistently maintain.

Lingo, my first bestseller, is about sixty European languages. They all have their own chapters, which are therefore short and sweet. (Here are some reviews.) Lingo has been published in twelve languages.

Babel, which has seen editions in seven scripts representing fifteen languages, is about the twenty most widely-spoken languages in the world. Since these stories are roughly three times as long as those in Lingo, Babel had appealed even more to language enthusiasts. (More reviews.)

Not a book but a board game, The League of the Lexicon was developed and written by Joshua Blackburn of Two Brothers. My contribution is the Global Edition, an expansion set consisting of 500 multiple-choice questions about languages other than English.

And then there’s my song Mother Tongue. Listen to it here.

July 5, 2022

Reading ‘Western European’ through a Dutch lens

I’ve just published a Dutch-language book titled Seven Languages in Seven Days. It teaches the Dutch and Flemish reader how to read Danish. Norwegian, Swedish, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese and West Frisian based on the languages they already know: their native Dutch, their (semi-)fluent English and their typically rusty school German and French. For them, I made this video.

This book could also be written – not simply translated, because it will require quite an overhaul – for speakers of German and the Scandinavian languages. To make the video accessible for them, I’ve added English subtitles (machine-translated and lightly edited). But of course, if you’re a native speaker of yet another language, such as English, you’re still cordially invited to have a peek. Be welcome!

By the way, I’m delighted to say that the book has been very successful in the first three weeks of its life. Loads of media attention, extremely positive response from potential readers and even an official bestseller listing – my first ever in the Netherlands. There was even a great blogpost in English about it, written by my Portuguese language friend Marco Neves.