Gaston Dorren's Blog, page 11

November 29, 2015

Etymologising through my hat?

Business deals that seem too good to be true usually are, and the same is true for etymologies.

Business deals that seem too good to be true usually are, and the same is true for etymologies.

This morning, I came across the Turkish word şapka, pronounced /shapka/, for ‘hat’. It reminded me of the French word chapeau, and I thought the -ka ending sounded just like a Russian diminutive, as in babushka (little grandmother) and balalaika (little babbler).

Now, it is a fact that Turkish has borrowed a lot from French, and it’s another fact that Turks and Russians had close relations for centuries (though words mostly went from Turkic languages to Russian rather than the other way round). But surely it would be silly to think that Turkish might first have borrowed a noun from French and then slapped on a Russian suffix.

As indeed it hasn’t. But my fleeting intuitive association was surprisingly spot-on after all – both good and true, for once. Turkish has borrowed şapka in its entirety from Russian, and this shapka was indeed formed from of a diminutive suffix -ka and a mediaeval (!) loan from French: either chape or its diminutive chapel; chapeau is very close to both of them.

And what’s the use of all this, you may well ask? Well, for one thing it’s a reminder that Turks and Russians weren’t always at each other’s throats, as they were last week – though admittedly, there has been a lot of that, too. And in practical terms, I’m unlikely ever to forget either the Turkish or the Russian word for ‘hat’. Now that I’m studying both languages a bit, that’s a truly good deal.

October 29, 2015

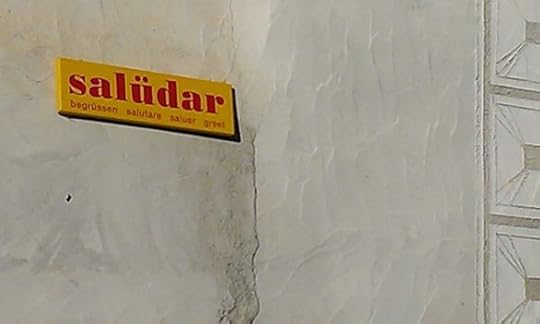

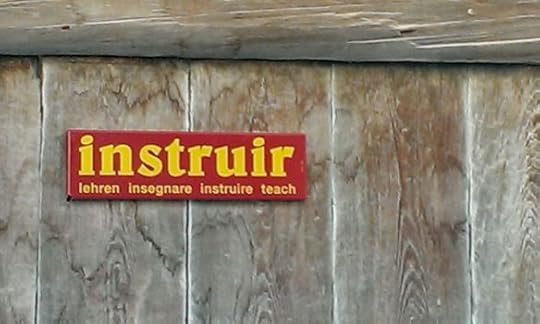

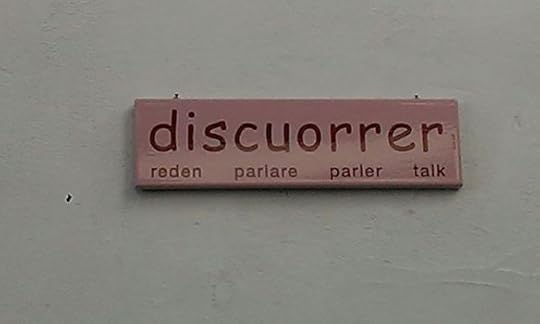

Open-air dictionary

The tiny Swiss village of Vnà got an entry in my app Language lover’s guide to Europe after its inhabitants – all 70 of them – turned the place into an open-air dictionary of the local Romansh language. They simply stuck signs to their houses with single Romansh words and their translations into German, Italian, French and English. A friend of mine who is there right now just sent me a couple of pictures. Here they are.

Photos by Michel Jehae.

October 25, 2015

The first scribbler of Western Europe

Throw your mind back to the very first time you tried your little hand at writing. With the unfamiliar pen between your fingers and your tongue between your lips, you gave of your best, but unless you were a calligraphic child prodigy, the result was, well, nothing to write home about. It looked shaky and straggly and, in a word, messy. Yet it didn’t stop your parents from being touched by your scribbles.

Call me weird, but that’s how I too felt earlier this week when I visited the Epigraphic Museum in Rome’s Baths of Diocletian. As its name and location suggest, it focuses on inscriptions from Antiquity, predominantly in Latin. Many of them look vaguely familiar: for the last five centuries or so, inscriptions in European and New World monuments have tended to emulate the Classical example. If you wonder what I’m talking about, open a new document in Word, choose the Times New Roman typeface and write a line in capitals.

The Praeneste fibula. Or rather a copy of it, unfortunately. The original is kept in a museum for prehistory (?!) in some Roman suburb.

Besides the many inscriptions on slabs of stone, there were also some short texts on small objects. There was one that I’d heard of before: a brooch known as the Praeneste fibula (see photograph, click to enlarge), dating from the seventh century BCE. On it are the words Manios med fhe fhaked Numasioi, which in Classical Latin would read Manius me fecit Numerio and in English ‘Manius made me for Numerius’. The phrase is rather archaic: the grammar, the shape of several letters and even the right-to-left direction of writing.

I enjoyed seeing it, but what touched me was another item: a simple clay pot. Found in an eighth-century BCE woman’s tomb, some 12 miles east of Rome, it displays just 5 characters (I would have guessed 4; see and click picture). They form the oldest extant text in Europe outside Greece. According to experts, the letters are Greek, though they’re not all that easily identifiable. The language might be Greek too: read as eulin, the text means ‘she who spins well’; read as eunin, ‘resting place’. But perhaps we should read it from right to left, which gives us the Old Latin ni lue or ‘don’t steal’.

I enjoyed seeing it, but what touched me was another item: a simple clay pot. Found in an eighth-century BCE woman’s tomb, some 12 miles east of Rome, it displays just 5 characters (I would have guessed 4; see and click picture). They form the oldest extant text in Europe outside Greece. According to experts, the letters are Greek, though they’re not all that easily identifiable. The language might be Greek too: read as eulin, the text means ‘she who spins well’; read as eunin, ‘resting place’. But perhaps we should read it from right to left, which gives us the Old Latin ni lue or ‘don’t steal’.

The writing is impressively old but, frankly, not very good. We are looking here at the pothooks of a less than competent scribbler. But then, he is the first Italic scribbler whose work has come down to us. And given that Western European writing began in Italy, the letters on this pot can be considered our first scribbles, dating from the time when we were learning the skill.

Hence my emotion.

Having enjoyed Rome so much – it was my first time there – I’d like to share some of the language-related treasures I saw.

The Epigraphic Museum mentioned above, which is part of the Roman National Museum, has much more to offer than just a brooch, a pot and some more inscriptions in Old Latin. Let me mention a few other highlights:

A survey of Old Italy’s numerous alphabets, from Greek and Etruscan to Roman and Faliscan.

A survey of Old Italy’s numerous alphabets, from Greek and Etruscan to Roman and Faliscan.Specimens of all sorts of (non-literary) writers, writings and methods of writing (see and click picture above).

A short video about the craft of stonemasonry, showing how inscriptions were (and still are) made.

A large number of inscriptions from the Classical era. One of the most remarkable items contains the puzzling letter Ⅎ. It was Emperor Claudius who substituted this for the consonant V, to distinguish it from the vowel V: in this spelling, the original name of Virgil would be ℲERGILIVS. After Claudius’ death, the new-fangled character immediately fell out of use. Apparently it takes more power than even a Roman emperor had to overcome spelling conservatism.

The Capitoline and Vatican Museums, both worth a visit for many reasons, have additional attractions for the language enthusiast. The former includes a small section, situated at the beginning of the tunnel between the old and the new buildings, that focuses on ancient languages. It tells the visitor about Roman language policy and shows inscriptions in several languages, including Hebrew and Palmyran, the Assyrian dialect of Palmyra – the

city now in the throes of destruction by IS bedlamites.

The Vatican’s Etruscan Museum contains several works of art with inscriptions in the largely undeciphered Etruscan language, as well as one in Gallic, the Celtic language of Gaul (see picture). The Egyptian Museum, a few doors down the corridor, has a good deal of hieroglyphic and some hieratic writings on display. However, I’m embarrassed to say that, what with all the obelisks scattered around the old city, I had seen my fill of hieroglyphs. Rome is so rich that this is how blasé it can make you.

The Vatican’s Etruscan Museum contains several works of art with inscriptions in the largely undeciphered Etruscan language, as well as one in Gallic, the Celtic language of Gaul (see picture). The Egyptian Museum, a few doors down the corridor, has a good deal of hieroglyphic and some hieratic writings on display. However, I’m embarrassed to say that, what with all the obelisks scattered around the old city, I had seen my fill of hieroglyphs. Rome is so rich that this is how blasé it can make you.

****

More specialised tourist information about Rome and other European cities can be found in the Language Lover’s Guide to Europe, an inexpensive app available for Android and iOS.

September 23, 2015

Thir house teen

Here’s something I would have added to chapter 35 of Lingo if only I had known it at the time. According to Swedish linguist Mikael Parkvall, several Celtic languages have discontinous numerals. The example he mentions is from Irish: while the word for 13 is trí déag, ‘13 houses’ is trí theach déag, with the word for ‘house’ in the middle. ‘Thir house teen’ would be a clumsy rendering in English. These Celtic complications are not entirely unique, Parkvall adds: several African and indigenous American languages display similar phenomena. If you like this sort of thing, get your hands on a copy of his book Limits of language, as it’s full of nuggets like this.

Here’s something I would have added to chapter 35 of Lingo if only I had known it at the time. According to Swedish linguist Mikael Parkvall, several Celtic languages have discontinous numerals. The example he mentions is from Irish: while the word for 13 is trí déag, ‘13 houses’ is trí theach déag, with the word for ‘house’ in the middle. ‘Thir house teen’ would be a clumsy rendering in English. These Celtic complications are not entirely unique, Parkvall adds: several African and indigenous American languages display similar phenomena. If you like this sort of thing, get your hands on a copy of his book Limits of language, as it’s full of nuggets like this.

While checking Parkvall’s claim about Irish, I stumbled upon another numerical curiosity. Finnish has two ways of expressing certain numbers, Croatian linguist Jadranka Gvozdanović writes in her Indo-European numerals. 28, for instance: the usual word is kaksikymmentäkahdeksan, made up of twenty (kaksikymmentä) and eight (kahdeksan) – a compound unremarkable for all but its length. However, there’s an alternative way of saying 28, namely kahdeksan kolmatta, and while it’s much less common, a Google search does turn up more than two score and ten contemporary uses. ‘Eight’ (kahdeksan) comes first this time, followed by kolmatta, literally ‘of the third’. So now 28 is analysed not as 20 plus 8, but as 8 of the third ten, with the first and second tens assumed.

These two approaches to the number 28 are somewhat reminiscent of our own two ways of telling the time. When we read the clock on the left as ‘seven fifty’, we take the past full hour as our reference. When we say ‘ten to eight’, on the other hand (not the clock hand!), we are anticipating the next full hour. That’s similar, I think, to the Finns’ calling 28 ‘eight of the third’.

These two approaches to the number 28 are somewhat reminiscent of our own two ways of telling the time. When we read the clock on the left as ‘seven fifty’, we take the past full hour as our reference. When we say ‘ten to eight’, on the other hand (not the clock hand!), we are anticipating the next full hour. That’s similar, I think, to the Finns’ calling 28 ‘eight of the third’.

August 28, 2015

My (or rather Ann’s) time in Edinburgh

I’ve just returned from a five-day visit to the Edinburgh Book Festival. Worth a report, of course – except that in the meantime other things have piled up, all clamouring for my time. So I’m happy to find that Ann Morgan (of Reading the World fame and the nicest stage-mate I could have wished for) has managed to look back at the festival, including the several things that we attended together. Here then are her experiences, quite a few of which are similar to my own.

I’ll admit it: I was nervous. Although my quest to read the world has taken me on many adventures and seen me speaking to a wide variety of audiences – from 20 Women’s Institute members in a school hall in Lee to 300 Procter & Gamble employees in Geneva – I had never faced a challenge quite like this. As I walked into the authors’ yurt, backstage at the Edinburgh International Book Festival, I couldn’t help being aware that I was here to take part in one of the most renowned literary events in the world.

Now, I’ve been in a yurt or two before (I once gave a talk in one in Canterbury), but I have never seen one to compare to this. Sprawling over an area about twice the size of my flat, it was made up of a series of conjoined octagons, which created pleasing little alcoves…

View original post 836 more words

July 26, 2015

Feline lingerie (2)

In December, I wrote a post on the etymology of the word panties, tracing it back to a 3rd-century Greek saint, Pantaleon, whose name I translated as ‘all lion’. The tiniest of discoveries, of course, but a nice little piece of work all the same, or so I felt.

In December, I wrote a post on the etymology of the word panties, tracing it back to a 3rd-century Greek saint, Pantaleon, whose name I translated as ‘all lion’. The tiniest of discoveries, of course, but a nice little piece of work all the same, or so I felt.

Imagine my chagrin when I recently discovered that Mark Forsyth had included this very connection between underwear and a Christian martyr in his book The Etymologicon. And to make things worse, I must have come across this factlet well before I wrote the blogpost, because I read the book a good while back. Amazingly, the link never even sounded familiar. This may be a case of entertainment-induced amnesia: Forsyth’s books (plural, since I also read his Elements of eloquence) tickle my brain in such a clever and amusing way that it switches to comedy mode and fails to memorise anything much.

Besides chagrin, I also got a nasty shock. His and my etymological explorations yielded the same results but for one thing: the translation of the saint’s name. According to him, Pantaleon was Greek for ‘all-compassionate’ – a far cry from my ‘all lion’, and obviously more befitting for a saint. I immediately felt that I was due to be wrong, because The Etymologicon was, after all, a book and I was just a person. Absurd, I know, utterly absurd. But things need not make sense to upset one.

Having pulled myself together, I delved into the matter. The Greek and German Wikipedias helpfully explained that the saint had two names. His given name was Pantoleon or Pantaleon, depending on which Wikipedia you believe. The other name – accorded to him by God, the German source specified – was Panteleimon, and this is the one that means ‘all-compassionate’. Both names could have produced the word panties, but since we also have pantaloons and French pantalon, clearly Pantaleon was the one that did. And what little Greek I know strongly suggests that this means ‘all lion’.

Ha!

But even as I was cheering, I carelessly took a peek at the French Wikipedia for further confirmation. What I got instead was another twist to the story. Pantaleon was merely a Latin corruption of Panteleimon, it claimed: meaningless in itself, but misinterpreted by the Romans (and by me) as ‘all lion’. So if this was correct, Forsyth and I would both be in error, but me more so than him.

Fortunately, the French Wikipédistes seem to have got the wrong end of the stick. A lot of other sources are agreed that Pantaleon does indeed mean ‘hole lion’ (ganzer Löwe – the German Wikipedia again) or ‘in all things a lion’ (in alles een leeuw – a Catholic website) or ‘in all things like a lion’ (an Orthodox wiki).

So I seem to have beaten Forsyth after all. Sorry, Mark. We all make mistakes. And I love The Etymologicon all the same.

June 16, 2015

Edinburgh and Audible

Two pieces of exciting good news. Well, I’m excited.

The one thing is that, at long last, I’m allowed to spread the word that I’ll be participating in the Edinburgh Book Festival. On Monday 24 August, at 2 pm, I’ll be interviewed abut Lingo in the Baillie Gifford Corner Theatre. I’ll share the honour with fellow author and journalist Ann Morgan, who wrote Reading the world. Later that day, I’ll participate in The Revolution Will be Tweeted, an event organised by Amnesty International, where four authors will be reading some work (not our own) around the use of social media in social activism. I’ll spend several days in Edinburgh, so I may be available for a chat about language over a cup or glass.

The one thing is that, at long last, I’m allowed to spread the word that I’ll be participating in the Edinburgh Book Festival. On Monday 24 August, at 2 pm, I’ll be interviewed abut Lingo in the Baillie Gifford Corner Theatre. I’ll share the honour with fellow author and journalist Ann Morgan, who wrote Reading the world. Later that day, I’ll participate in The Revolution Will be Tweeted, an event organised by Amnesty International, where four authors will be reading some work (not our own) around the use of social media in social activism. I’ll spend several days in Edinburgh, so I may be available for a chat about language over a cup or glass.

Second, there is a new edition of Lingo in the making, the fifth in all: an audio book! Audible have bought the rights. I happen to have an Audible subscription myself, so I know that they have lots of great and well produced stuff. I’m awfully pleased to see my Lingo mingle there with other books that I’ve enjoyed, by writers ranging from P.G. Wodehouse to Steven Pinker and from Jasper Fforde to Anton Chekhov.

Second, there is a new edition of Lingo in the making, the fifth in all: an audio book! Audible have bought the rights. I happen to have an Audible subscription myself, so I know that they have lots of great and well produced stuff. I’m awfully pleased to see my Lingo mingle there with other books that I’ve enjoyed, by writers ranging from P.G. Wodehouse to Steven Pinker and from Jasper Fforde to Anton Chekhov.

May 27, 2015

Five reasons to vote (for me)

The goddess of gorgeous victory

My language blog has been included in this year’s Top 100 Language Professional blogs, which is the kick-off for the annual competition organised by the international multilingual language and translation portal bab.la and the Lexiophiles blog.

You see where I’m heading: I want to win, and therefore, I want your vote. If you’re willing to oblige, just click here and find me under the letter G of my first name, Gaston.

There is a snag, though: the nominee is not this blog, languagewriter.com, but its Dutch-speaking twin sister, taaljournalist.nl. You may not mind, of course. That’s great; I love you already, in an opportunistic sort of way. (Have you voted yet?) But if you feel that you cannot possibly vote for a blog that you’re unable to read, who am I to argue that point? Well, the blogger himself, that’s who, and I’m going to argue it like nobody’s business.

1) Being the language lover you are, you’ll agree that blogs in languages smaller than the Big Western Handful (English, French, German, Spanish and Portuguese) have a serious handicap on the international stage in terms of visitor numbers, media attention and awards. This is your opportunity to do something about it.

2) If you like this website, let me assure you that its Dutch counterpart is even better. It has more and more varied content, livelier discussions and a more polished and personal style. Some of the posts will even make it into a book, to be published early next year.

3) If you liked Lingo and want to read more, vote for me. Publicity sells books, which enables me to spend time writing new ones. I am working on one, and I think it’s going to be a corker. Sorry I can’t disclose more yet.

4) This Sunday, I’m turning fifty. (You don’t think I would admit that if it weren’t true, do you?) So why not give me a little gift at no cost to yourself?

5) (Add you own persuasive point here.)

Five convincing reasons to vote for my blog: that should do the trick, I think. Finally, let me quote the Greek goddess of victory: Just do it. Do it here, and now.