Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 588

November 25, 2011

I remember Black Pete

As a child, I never believed in Santa Claus.

I believed in Saint Nicholas and Zwarte Piet (Black Pete). I remember waking up as a child on December 6, 1983, three hours before daybreak. I also remember waking up early on December 6 for years afterwards. Always early, always too excited to go back to sleep the night Saint Nicholas came by our house. Over the years, I got to share this rush of euphoric anxiety with my two younger brothers. We would be jumping on our beds, calling our parents, yelling out to ask whether it was time yet. They were never amused. My brothers and I knew there was no way we could pussyfoot downstairs into the living room to see which presents He had left us. Because each year, Saint Nicholas's black servants, those sneaky Black Petes ('Zwarte Pieten') would have locked the room's door on their way out.

You know Black Pete?

I remember sitting in our classroom when there was a sudden banging on the window. I would first see a pair of gloved hands throwing candies against the glass. Next thing we knew, the classroom's door would be flung open, and in stormed two Black Petes, spraying the floor with marzipan cookies. We all dove under our desks, grabbing as many sweets as we could fill our mouths with. The Black Petes then ordered us to follow them. We rushed out in total chaos: there's no way the teacher could hold us back.

Although he was a ubiquitous feature in my childhood, in 2011, Black Pete stands in the docks, again, charged of blackface, and all the attendant racism attached to cultures that employ this form of costumery to evoke what they imagine to be attached to 'blackness'. Why, Black Pete's accusers ask, can we possible be tolerant toward the annual dressing up by men and women alike as curly haired, black-faced, red-lipped servants to a holy white man? Why do people in the Netherlands allow for this ritual to continue? A ritual that so bluntly flies into the face of anybody who finds the staging offensive, who considers the practice despicable; a yearly, publicly accepted rehashing of colonial stereotypes?

I remember standing in the school yard: we're watching the Black Petes, sometimes in awe of their acrobatic skills, more often laughing at their silliness. We're waiting for Saint Nicholas to arrive on his white horse. He's visiting our school! We sing. The Black Petes urge us to sing louder: "He won't come, if He can't hear you!" We sing with even more zeal: "Please, Saint Nicholas, do come in with your servant, because we're all sitting upright / Maybe you have some time for us, before you ride back to Spain." (Saint Nicholas lives in Spain, Santa in the North Pole.)

Little did I know, back in the eighties, that already there were early attempts to get rid of this figure. The first official protest on record is by a woman named M.C. Grünbauer who, in 1968, thought "it no longer appropriate to continue to celebrate our dear old Saint Nicholas feast in its actual form." While slavery has been abolished for over a century, she says, "we continue the tradition of presenting the black man as a slave. The powerful White Master sits on his horse or throne. Pete has to walk or carry the heavy sacks."

Since the 1980s, historian John Helsloot reminds us (that's him doing the soul-searching in the video above), it is mostly black people who try to convince the Netherlands of the offensiveness of the figure of Black Pete. Young Surinamese who emigrated to the Netherlands in those years, carrying with them the discrimination by white Dutch colonials in their home country, called out their former colonial masters over their racist ritual. Many temporary protest committees (varying from angry individuals to more organized groups) have lashed out at the practice ever since. Some of them were successful (up to the point where the Netherlands once experimented with introducing Red and Blue Petes–unfortunately, the Dutch public would have none of it), while the majority has silently disappeared from the stage.

I remember sitting in the school's sports hall, frantically trying to think of something I might have done wrong that year, when Saint Nicholas calls my name in front of the other school kids. There were hundreds of us. Uneasily but patiently, we all wait our turns. It made for long Friday afternoons and we loved every minute of it. But if I had done something bad, I would be punished. I would be put to shame in front of my friends. Worse, I wouldn't get my chocolate. And if I had done something really bad, Black Pete would put me in the bag he had slung over his shoulder, now void of all candy, and take me with him to Spain. It never happened. Fighting with your brothers turned out not bad enough a mischief. Nevertheless, I would hold on tightly to my candy, those afternoons, side-eyeing Black Pete.

Public attention (including a praised photo series by British photographer Anna Fox) and protests surrounding the Dutch obsession with maintaining this tradition of black caricature have come and gone over the years. So why would this year's protests be any different? Because earlier this month, one of those small protest groups –four people does constitute a group, one of them you remember as rapper Kno'Ledge Cesare– made it online and into the national media. Planning to peacefully rally wearing T-shirts with the printed slogan 'Black Pete is Racism' during the annual arrival of Saint Nicholas in the Dutch city of Dordrecht, they were caught off guard by the police, abused and their unrolled banner confiscated. They were also detained by the police.

The police should have thought twice, what with those cellphones around. It didn't take long for the images to surface on the web.

Online support for the claims of the detained group of protesters has grown since. And I concur.

Black Pete and St. Nicholas were so real to me that I remember asking myself what I would do, once in Spain, and released from the sack. And pondering how to make my way back home. But I also recall –in my third year of primary school, in that same sports hall– somebody I looked up to whispering into my ear: "He isn't real, you know."

That I'm writing this from Belgium–the Flemish speaking part of which has the exact same tradition; we share Holland's language, and some history–where there is no debate around the figure of Black Pete whatsoever proves we've got some work to do. That there's not a peep against this caricature goes to show that here in Belgium, Black Pete (although we adults know that he's not 'real'), is very much alive. If the French, the Swiss, the Germans and the Austrians can have Saint Nicholas without Black Pete, why is it that we have so much trouble letting him go?

*After Denis Hirson's I Remember King Kong.

November 23, 2011

Found Objects No.19

Born in London to a Moroccan mother and an Iraqi father, Tala Hadid completed her 12-minute short thesis film Your Dark Hair Ihsan in 2005. Recorded in Morocco and its Rif Mountains, the film was awarded the Cinecolor/Kodak Prize (2005) and the Panorama Best short Film Award at the Berlin Film Festival (2006).

Palm Wine Mixtape

It's been awhile since I could call actually call something a Mix-Tape.

But I can do that for this interesting looking project from Simone Bertuzzi, African music enthusiast and blogger at the Palm Wine site. Side one is his field recording at the Master Musicians of Joujouka Brian Jones Festival 2009 in Tangiers, Morocco. Side two is a mix by DJ Rupture and Maga Bo done this past summer while on a train, also in Morocco, during their Beyond Digital project.

Read the story behind the project here.

There is also a very nice looking Palm Wine Picó being made in Colombia right now!

'The return of the one party state'

By Mats Utas, Guest Blogger

Most supporters of the opposition Congress for Democratic Change followed the recommendation of their party leader and restrained from voting on November 8. The election results show this with all clarity. After counting all the votes NEC showed that Johnson Sirleaf and the Unity Party had received more than 90%. Johnson Sirleaf has declared that she wants an inclusive government working for national unity, and there is clearly a need for this after the election period laying bare such cracks of conflict. Socio-political cracks are twofold: first between different regions within the country, and secondly between those who have and those who have not. These rifts are not new, but were rather central tenets of the civil war as well. For long term stability the Liberian government must in a comprehensive way deal with these issues – something that the UP has during their last period in office by and large failed to do. A further problem appears to be a centralisation of power to the UP. In fact they managed to "buy" up most of the smaller parties, with supporters and all, after the first round, and made deep inroads in the CDC opposition. This appears to be an obstacle for real democratic transition, and critical voices in Monrovia have started talking about the return of the one party state.

Last week I had a longer talk with an expat in the business community. The person has spent much of the last fifteen years in the country and knows both war and peacetime Liberia extremely well. Here are some basic ideas from our chat and some additional observations made be me:

Security. The security situation particularly in Monrovia is of great concern. Currently the security apparatus has less control of the situation than during the years under the Taylor government. The root according to him is extensive poverty where crime of various kinds to many is a way to get by; simply surviving. At present time it is important to underscore that it is far from ex-combatants only who are involved in urban crime. The situation is better in other parts of the country, but in Grand Gedeh there are serious security concerns after armed elements have returned from the unrest in Côte d'Ivoire. It should however be recalled that for some citizens hailing from the Liberian south-east the security provided during the time of Taylor was precarious to the extent that many were not safe travelling in large parts of the country.

Big Men and informal networks. This is a special interest of mine. I have edited a book on the topic, African onflicts and informal power, that will be published by Zed Press early next year. In relation to Anders Themnér's and my project on former mid-level commanders I will write more about that, but from my discussion with the expat businessman I have a few notes on the politico-economic climate in Monrovia regarding the elections. Around government and ministers there are a number of networks that must be considered in order to make business. This is intimately linking business and politics. In order to be successful you must be part of Johnson Sirleaf's people. Corruption is still a central concern and in most cases payment under the table is necessary (see below) – it is in many ways the glue of the informal networks. There are still some wealthy businessmen with money originating from the days of Charles Taylor; the Lonestar telecommunication company is the largest. This group of people made their money during the war and under Taylor's presidency and today have a fragile truce with the UP government. One of the wealthiest Cyril Allen, former chairman of the NPP, did greatly upset Johnson Sirleaf, by sponsoring the CDC election campaign. Allegedly Johnson Sirleaf had promised to help lift his travel ban in case he would support her. Some other pro-Taylor politicians chose to stand as independents in this election (most importantly Daniel Chea and Edwin Snowe – the latter with the formidable slogan "it will Snow"), a sign of their willingness to shift to UP. Taylor's old party NPP, lead by his wife Jewel Taylor, threw its lot behind CDC in the second round, but my guess is that in a longer perspective many more of the Taylor crowd, his "pepper bush", will appear on the UP side once Taylor is sentenced by the Special Court for Sierra Leone and his loyalists are ascertained that he will not reappear in Liberia. If he on the other hand will be released, political power will be shifted back to him (and he is still very popular among the people) and some of the assets and profits from within the Taylor business sphere will be awarded Taylor.

Natural resource boom. There is currently a big interest in natural resources and Liberia has the potential of becoming a very wealthy country if they are exploited in a good way. Liberia has however always been plagued by informal deals with big international companies, government officials and a variety of brokers receiving extraordinary profitable deals and money under the table. During the time of the utterly corrupt interim government under Gyude Bryant Liberia started auctioning predominantly off-shore oil concessions (but also one on-shore). A global witness report has unravelled several cases of corruption, and observers with good insights in the business points out that contracts signed with the current government is given much lower income to the government than is normal in the business (the recent deal with Chevron and a Nigerian company has supposedly given Chevron 70% and the Nigerian company 30% of incomes, whilst Liberia is totally left out. In regular contracts the government should receive 20-30% – but now the only income they will get if oil is eventually pumped up is from tax). Similar contracts with much too limited incomes for the government is signed in all sectors of the natural resource market suggesting that government officials involved in signing such contacts are in the receiving end of considerable bribes.

Problems in the bank sector. The Government of Liberia has signalled their interest in boosting the business sector, but this appears to be true only for large companies. In the mean time it is almost impossible for mid-size business to obtain bank loans in Liberia. Even though companies can put land and property as security Liberian banks typically refuses to give out loans. Instead these companies are approached by bank employees informally offering private loans on short term basis. You can receive 2000 USD from a bank employee on a ten days basis and having to pay back 2500. This is seriously hampering the possibilities for smaller companies who are not part of the government "circle". On the other hand people within this circle can get loans even without any form of security.

Son of the President. Robert Sirleaf is allegedly increasingly involved in all sectors of natural resource extraction (but also demanding bribes from smaller companies). It is believed by some that most large scale deals are brokered by him. He was for instance involved in the recent oil deal with Chevron. Although it should also be acknowledged that Robert Sirleaf is involved in many community development projects, it is interesting to note how yet another son of the President is reaching notoriety. Charles Taylor's son Chuckie led the feared ATU unit during his father's presidency and a few years ago he was sentenced to 97 years in US prison for among other things severe torture committed in Liberia. Although economic crime and torture is not the same, crime is crime is crime, as Maggie Thatcher once said.

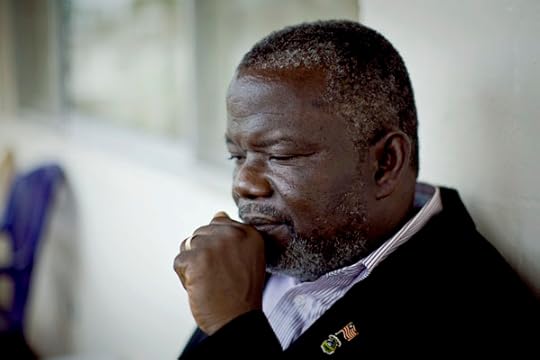

Photo Credit: Glenna Gordon

The return of the one party state

By Mats Utas, Guest Blogger

Most supporters of the opposition Congress for Democratic Change followed the recommendation of their party leader and restrained from voting on November 8. The election results show this with all clarity. After counting all the votes NEC showed that Johnson Sirleaf and the Unity Party had received more than 90%. Johnson Sirleaf has declared that she wants an inclusive government working for national unity, and there is clearly a need for this after the election period laying bare such cracks of conflict. Socio-political cracks are twofold: first between different regions within the country, and secondly between those who have and those who have not. These rifts are not new, but were rather central tenets of the civil war as well. For long term stability the Liberian government must in a comprehensive way deal with these issues – something that the UP has during their last period in office by and large failed to do. A further problem appears to be a centralisation of power to the UP. In fact they managed to "buy" up most of the smaller parties, with supporters and all, after the first round, and made deep inroads in the CDC opposition. This appears to be an obstacle for real democratic transition, and critical voices in Monrovia have started talking about the return of the one party state.

Last week I had a longer talk with an expat in the business community. The person has spent much of the last fifteen years in the country and knows both war and peacetime Liberia extremely well. Here are some basic ideas from our chat and some additional observations made be me:

Security. The security situation particularly in Monrovia is of great concern. Currently the security apparatus has less control of the situation than during the years under the Taylor government. The root according to him is extensive poverty where crime of various kinds to many is a way to get by; simply surviving. At present time it is important to underscore that it is far from ex-combatants only who are involved in urban crime. The situation is better in other parts of the country, but in Grand Gedeh there are serious security concerns after armed elements have returned from the unrest in Côte d'Ivoire. It should however be recalled that for some citizens hailing from the Liberian south-east the security provided during the time of Taylor was precarious to the extent that many were not safe travelling in large parts of the country.

Big Men and informal networks. This is a special interest of mine. I have edited a book on the topic, African onflicts and informal power, that will be published by Zed Press early next year. In relation to Anders Themnér's and my project on former mid-level commanders I will write more about that, but from my discussion with the expat businessman I have a few notes on the politico-economic climate in Monrovia regarding the elections. Around government and ministers there are a number of networks that must be considered in order to make business. This is intimately linking business and politics. In order to be successful you must be part of Johnson Sirleaf's people. Corruption is still a central concern and in most cases payment under the table is necessary (see below) – it is in many ways the glue of the informal networks. There are still some wealthy businessmen with money originating from the days of Charles Taylor; the Lonestar telecommunication company is the largest. This group of people made their money during the war and under Taylor's presidency and today have a fragile truce with the UP government. One of the wealthiest Cyril Allen, former chairman of the NPP, did greatly upset Johnson Sirleaf, by sponsoring the CDC election campaign. Allegedly Johnson Sirleaf had promised to help lift his travel ban in case he would support her. Some other pro-Taylor politicians chose to stand as independents in this election (most importantly Daniel Chea and Edwin Snowe – the latter with the formidable slogan "it will Snow"), a sign of their willingness to shift to UP. Taylor's old party NPP, lead by his wife Jewel Taylor, threw its lot behind CDC in the second round, but my guess is that in a longer perspective many more of the Taylor crowd, his "pepper bush", will appear on the UP side once Taylor is sentenced by the Special Court for Sierra Leone and his loyalists are ascertained that he will not reappear in Liberia. If he on the other hand will be released, political power will be shifted back to him (and he is still very popular among the people) and some of the assets and profits from within the Taylor business sphere will be awarded Taylor.

Natural resource boom. There is currently a big interest in natural resources and Liberia has the potential of becoming a very wealthy country if they are exploited in a good way. Liberia has however always been plagued by informal deals with big international companies, government officials and a variety of brokers receiving extraordinary profitable deals and money under the table. During the time of the utterly corrupt interim government under Gyude Bryant Liberia started auctioning predominantly off-shore oil concessions (but also one on-shore). A global witness report has unravelled several cases of corruption, and observers with good insights in the business points out that contracts signed with the current government is given much lower income to the government than is normal in the business (the recent deal with Chevron and a Nigerian company has supposedly given Chevron 70% and the Nigerian company 30% of incomes, whilst Liberia is totally left out. In regular contracts the government should receive 20-30% – but now the only income they will get if oil is eventually pumped up is from tax). Similar contracts with much too limited incomes for the government is signed in all sectors of the natural resource market suggesting that government officials involved in signing such contacts are in the receiving end of considerable bribes.

Problems in the bank sector. The Government of Liberia has signalled their interest in boosting the business sector, but this appears to be true only for large companies. In the mean time it is almost impossible for mid-size business to obtain bank loans in Liberia. Even though companies can put land and property as security Liberian banks typically refuses to give out loans. Instead these companies are approached by bank employees informally offering private loans on short term basis. You can receive 2000 USD from a bank employee on a ten days basis and having to pay back 2500. This is seriously hampering the possibilities for smaller companies who are not part of the government "circle". On the other hand people within this circle can get loans even without any form of security.

Son of the President. Robert Sirleaf is allegedly increasingly involved in all sectors of natural resource extraction (but also demanding bribes from smaller companies). It is believed by some that most large scale deals are brokered by him. He was for instance involved in the recent oil deal with Chevron. Although it should also be acknowledged that Robert Sirleaf is involved in many community development projects, it is interesting to note how yet another son of the President is reaching notoriety. Charles Taylor's son Chuckie led the feared ATU unit during his father's presidency and a few years ago he was sentenced to 97 years in US prison for among other things severe torture committed in Liberia. Although economic crime and torture is not the same, crime is crime is crime, as Maggie Thatcher once said.

Photo Credit: Glenna Gordon

November 22, 2011

Global Genre Accumulation

Around the start of Occupy Wall Street, an international DJ called Samim tweeted, "Did you know that the richest 1% of DJ´s control over 80% of the industry´s wealth and over 70% the media coverage?#occupyDJs". Perhaps it was meant as an off-hand joke, but the fact that the DJ industry is an unbalanced place in terms of representation is clearly a reality. Nothing materialized this notion more than DJ Mag's annual Top 100 DJs list, which read like a Forbes' top 100, but for wealthiest DJs. Many people noticed the racial, gender, and wealth imbalances of the list, which in today's music world almost seems preposterous (or maybe not.) Also, considering that House and Techno music's roots are in the Black and/or Gay communities of the Rust Belt urban centers in the American Midwest, it becomes a curious example of cultural appropriation.

Noticeably absent from the list was popular American DJ, Diplo, who is also a successful producer, record label owner, and style icon. Perhaps the reason why he didn't show up in the list is because he explicitly prefers to align himself with a global contemporary "underground". Most recently he has done so in a series of travel journals for Vanity Fair magazine. The first one about this past year's Carnival in Trinidad and Tobago and the latest where he "Discovers the Last True Underground Club Scene in New York." In these travel journals Diplo makes clear his critical stance to the mainstream. But, with all the structural inequalities inherent in the industry, and qualifying statements like, "I don't know a lot about being black and gay and cool…" Diplo's critique mostly ends up sounding a lot like someone looking for redemption in a pure, untouched, uncontaminated, Other.

Why should you care about this? Because, no matter where you are in the world, if there's an underground dance scene or marginalized community, Diplo has probably "discovered," re-framed, and sold it audiences in another part of the world. If he hasn't yet, he's on his way, and your local scene might just end up being the next European House or Techno.

Critiques of Diplo's practices are not hard to come by. In a recent interview in GQ magazine, Diplo defended his practices, arguing that people in various global music scenes, like Jamaican dancehall, just want their music to reach larger audiences and that he facilitates their success. At the same time, his position as cultural authority has earned him gigs producing for acts like Beyoncé and No Doubt. Like here:

I'm not a scholar of Marx, but if I applied some of his basic principles on how Capitalism works, it's not too hard to fit someone like Diplo into the role of Value appropriator and distributor (he admits as much in the GQ interview.) Instead of coming from labor, Value in this instance is "street credibility" that is harvested from these underground sub-cultures. This credibility is what allows Diplo to have a career as an internationally touring DJ, and Hollywood tastemaker. But in order for Diplo to keep his position as mediator, he must reinforce the underground (Other) status of the scene he is revealing. This is especially evident when one realizes that scenes such as Dancehall, Carnival, and Vogue aren't really that "undiscovered" after all. Yet, exploitation in this manner is essential to the way Capitalism functions, so maybe it's not fair to blame one individual for his role in the greater system.

While I fit into both of the groups that Diplo seems to despise (academia and journalism), I am also a global urban dance scene practitioner. Perhaps it would be useful for me to turn to an example of more progressive trends I see, to illustrate the potential of DJing as a revolutionary cultural artform.

This past March, a Twitter "beef" broke out between Diplo and New York based DJ, Venus X. The basic crux of their back-and-forth centered on the attempt of Diplo to record one of Venus' sets. After he recorded her set, noticing that he performed a set similar to hers, and keenly aware of Diplo's reputation for "genre discovery", she decided to call him out for it. He claimed he was helping her get famous. She insisted that she didn't want to be discovered.

In the time since that moment of exchange on Twitter, Venus' popularity has grown, and she's won the types of consulting gigs that employ Diplo. I've also become more familiar with her work, and through the process of listening closely to two of her recent mixes, I've been able to clarify some of my own thoughts on what it means to be a DJ, and what differentiates her work to that of other DJs and tastemakers in similar positions in the industry.

The art of DJing is as postmodern as it gets. Its essence is appropriation. A DJ re-contextualizes pre-existing cultural expressions to resurrect or re-interpret cultural memory for an audience. For me, Diplo and Venus exemplify two different ways of doing this.

Diplo has become known for taking an "unknown" culture and exposing it to the world. He mixes dominant American culture cues, with "foreign" cultures, and positions himself as the "in the know" intermediary, in turn reinforcing a separation between audience and subject. Venus uses culture memory of various both underground and mainstream cultures to create safe spaces for, and communicate messages to groups that are underrepresented in mainstream cultural discourse (groups that she herself is a part of.)

A few weeks ago I heard Venus appear on DJ/rupture's Mudd Up radio show. I enjoyed her unorthodox technical style where she slowed down (screwed) her tracks, and then "drumming" the cue buttons on her CD-J's to emphasize certain sections of the songs she was playing. The syrupy chopped (percussive emphasis through "turntable" tricks) and screwed (slowing down) style isn't new (it comes from the Houston-Monterey cultural axis of Texas-Mexico border region), but Venus' framing of it (evident through their conversation) places it in a wider genre of American (Ghetto) Gothic, that mixes elements from a vast sub-section of underrepresented American culture (Latinos, Blacks, LGBT folks, NYC immigrants, hood dwellers, unemployed, underemployed, Drug Users, and generally economically depressed side of the American Rust Belt, not to mention women DJs!)

The day after her radio appearance, Venus released a mixtape with her partner $hane, who together make up part of the GHE20 G0TH1K crew. Still inspired by the radio appearance, I hurriedly downloaded and listened to the new mix on my A train commute from Brooklyn into Manhattan. Towards the end of the mix, someone in the crew was sampling and percussively chopping the dialogue that seemed familiar, from a teen movie that I couldn't quite place. I went home and googled words that I heard from the clip, "Sebastian" and "funeral." Up popped a clip of the final scene in the movie Cruel Intentions (I should have known better since that was in the name of the mix.)

Many of the comments on the video I saw were made by (what seemed like) teenage girls. I suddenly realized that there was a sub-section of American society that thought that what in my opinion was a forgettable movie, was one of the best movies of all time (which was clearly a product of niche marketing.) And then I realized, beyond being sex objects, teenage girls NEVER get repped or even really spoken to (beyond consumers of products that sell them as sex objects) in urban dance music. As the soundtrack of the movie started played the song "Bittersweet Symphony", I made a second realization. Venus and $hane had probably just ripped the track directly off youtube, and let the soundtrack play out to become part of the mix.

When a DJ chooses a song it's usually from memory. The best DJs have great musical memories, and can turn the vibe of a party based on this intuition. But musical memory is different from pop-culture memory. Not having a great movie memory myself, I've always been amazed at people who can instantly recite movie lines. $hane and Venus' sampling of a youtube clip, and DJing in a sort of reciting movie lines way, opens up the realm of DJing to a social and pop cultural intuition, beyond the realm of music nerds (like myself.) The art of DJing suddenly becomes more inclusive. Also, by re-framing this film, and pop-culture moment through their GHE20 G0TH1K lens, the crew subverts the niche marketing paradigm, using Hollywood produced pop-culture as a way to create an oppositional collective identity in an industry dominated by white males.

"Western" club DJs are often too stuck in the race for global genre accumulation, to see that the practice of discovery and exposure of Other's culture is always inevitably exploitative. In contrast, Venus X, GHE20 G0TH1K, Mike Q, and others that are doing similar work around the world today, are re-storing the cultural legitimacy of the DJ by creating safe spaces for underrepresented groups, and even allowing space for people from the dominant culture (like Diplo) to join in and feel safe. This is the same context that almost every mass-popular genre, like House, Hip-Hop, Reggae, Disco, and Dubstep came out of. Diplo's right that this whole DJ thing is supposed to be about community, but how does mainstream exposure benefit a community unless they have total control, and the means to collectively capitalize on that exposure? We're all still living in a system that has oppressed many of these "discovered" communities for centuries. As both a Western and African DJ (identities are complicated, no?), I believe that recognizing each others' subjectivity, yet acknowledging our mutual humanity can only lead to the more globally communal future that we all are fighting and hoping for. We should dance in the world we want to live in.

Batsumi's cascade of sound

By Dan Magaziner*

South Africa's 1970s are rightly remembered as a time of rising militancy. From the universities to the docks to the schools–the decade saw the rise of Black Consciousness and Steve Biko's calls for a radical reorientation of black culture towards the struggle for political and mental liberation. We curate our memorials to that decade with raised right fists and confrontations between uniformed students and uniformed police. But by choosing to title his column in the SASO Newsletter, "I Write What I Like," Biko called above all else for unapologetically creative responses to the tensions of the moment. Black South Africans answered this call in a variety of ways, some stridently political, others defiantly original. Oswald Mtshali, Mongane Wally Serote and others answered his call in words; Dan Rakgoathe, Winston Saoli, Louis Maqhubela and others on canvas. Batsumi answered with a cascade of sound.

Founded in Soweto in 1972, in 1974 Batsumi recorded an album that will be re-released later this week by Matsuli Music. The music is stunning, from the moment the album opens with Zulu Bidi's searching bass, and expands to include horns, flute, what sounds like a didgeridoo, drums, voices and Johnny Mothopeng's guitar. This is the past, reaching out to the present to remind us that we still don't understand. Today Biko and Black Consciousness's legacy as a political movement is contested and debated, invoked across the political spectrum and twisted to fit present-day concerns. But Batsumi is closer to the truth of that moment. This music doesn't preach, it doesn't declaim, it doesn't sloganize – but it also doesn't offer flee from the radical demands of its present. Indeed, although these tracks are not stridently political they are by no means escapist fare, suitable for shuffling dance steps at late night shebeens. Take the third track, "Mamshanyana." It opens with Mothopeng's acoustic guitar, the spare, patient twang of which could not be more different than the township jazz sounds we associate with this time period. (The amazing quality of this remaster is most apparent here, incidentally – you can literally hear the subtle reverb of the strings.) Drums, bass and organ, join, come together, voices crest, flute and sax echo. As it builds, it swings, coalescing into a uniquely compelling statement of intent. By the time and sax and flute solo over organ, bass and drums, Batsumi has got you.

And that's precisely the point. They have you nodding along in the same way that people respond to an accurate rendering of some richly remembered past. (Albeit with considerably more rhythm than that which attends to most story-telling.) It's fairly easy to see Batsumi in your minds eye – the township practice sessions, the clothes, the conversations – at the risk of cliché, you can practically smell the incense. But when they start to blow, or jam, or pound or chant, there's an abandon that demands our attention – the compulsion to express oneself, at a time when self-expression was radical and political in and of itself. Batsumi didn't need to respond to protests or apartheid or Bantu Education to be revolutionary. It just was, without ideology or partisan squabbling, no program necessary. That Johnny Mothopeng was the son of imprisoned PAC president Zephania Mothopeng didgeridoo is incidental; he played a mean guitar. His band played what they liked and what they played kicked ass. This was black consciousness, this was the 1970s. This was revolution.

The album can be previewed and pre-ordered here.

* Dan Magaziner, an assistant professor of history at Yale University, is the author of The Law and the Prophets, an intellectual history of South Africa between 1968 and 1977. The US edition can be ordered here; the South African edition here.

November 21, 2011

Queering the Congo

War photography forces us to ask questions about the limits of cultivating empathy via looking, and the limits of seeing self in the other when the image before us intimates something so violently different from the life experiences of the viewer. The troubling ethical questions that surround photographing conflict are centered around the attempt, by the photographer, to evoke a responsiveness for the distressed people within the photographs from the readers of these images – those who are almost never the subjects in the photographs, who are hardly ever 'one' with the subjects. Moreover, war photography often exploits our aversion and attraction to violence: when we see images of semi-starved people fleeing from burning homes, or eyes enlarged with terror, we are accosted by a double impulse: to simultaneously glare voyeuristically, and to look away.

Photography depicting danger to human habitation, the worst of human depravity, and the hell holes of the world where every breath signifies the precarious of all that which the viewer regards as sacred is meant to engage those whose safe lives are in stark contrast to such instability. Such images are meant to engage evoke both our awareness of the discord and difference between our lives and theirs; yet, they trigger uncanny feelings of familiarity. Inevitably, we ponder harrowing questions about our desire to regard such violations, while receiving a grotesque sort of sublime pleasure. Small wonder, then, that image-makers of warfare, who make a living out of constructing "statement photographs" of scarred lands and hopeless bodies, are often critiqued for the vicariousness and predatory nature of their photography. In the end, we are left wondering about the photographer's (and the audience's) complicity in brutalising those who are already in precarious positions by our intrusion into intimate, violent moments in their lives.

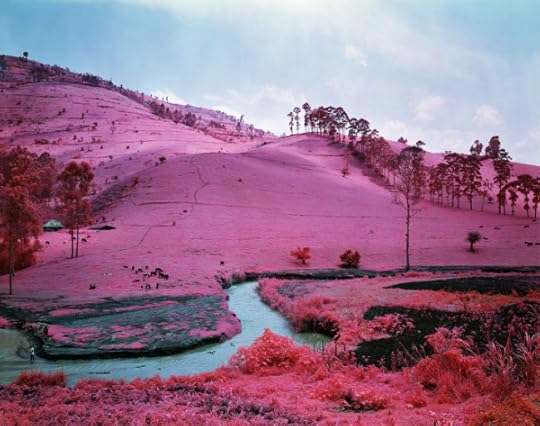

It is with all this disquiet about regarding the pain of others that I look with great wonder at Richard Mosse's Infrared images of eastern Congo, taken with Kodak's colour infrared film, Aerochrome. The film, Mosse explains, "was developed during the Cold War, in collaboration with the U.S. military, to read the landscape, detecting enemy infrastructure," and to render camouflage useless, thereby allowing the user to detect enemy positions in areas of dense vegetation. Civilians like "cartographers, agronomists, foresters hydrologists, glaciologists, and archaeologists" became fast friends of Aerochrome; soon thereafter, in the 1960s, its usage disintegrated into the world of kitschy psychedelic album art.

But the word psychedelic, Mosse points out, is tied to its Greek root: a soul-manifesting experience. What Aerochrome conveys, in Mosse's hands, is that manifestation of souls, in profane places, within profane bodies that we may believe to be devoid of the sacred. The quietness of the eloquent tremors delivered by his photographs may only communicate disturbing doses of aesthetic pleasure to those expecting the obvious shocks that are the bread-and-butter of statement photography. What we get, instead, is the photographer's invitation to us, the observer, to go beyond being told what to think by the black and white of the newsreel and charity speech. But because the images "disorder the aesthetics of conflict," notes artist Mary Walling Blackburn in an exchange with critical theorist A.H. Huber, they make us ask further questions about the "ethical dimensions" of suspending "the real"; we worry that the campiness conveyed by all that abundant pink, and the sublime escapism possible with beautifying the ugly are "modes of political disengagement," precisely because "the surreal quality of these images respond to our desire to be distracted from trauma at the moment of engagement, to float near, but not be engulfed" by the real (in Triple Canopy, "The Flash Made Flesh").

Much of Mosse's work sits apart from what was globally visible about the conflict in the eastern Congo. Mosse's use of Aerochrome attempts to engineer new ways of looking at the eastern Congo and its conflicts, beyond meaning-denuded statistics about the three million deaths, and what often seem like repetitive, boilerplate stories aimed for a 'Western audience. Mosse writes, in the essay introduction to his new book (Infra: Photographs by Richard Mosse, 2011), "I felt Aerochrome would provide me with a unique window through which to survey the battlefield of eastern Congo. Realism described in infrared becomes shrouded by the exotic, shifting the gears of Orientalism." It is the very ability to "shift" the photographer's and the viewer's Orientalist "gears" – those inevitable set of images, words, and conflicting emotions towards which our minds grind, the moment we hear the name, "Congo" – that allows Aerochrome's scarlet and pink dyes to manifest soul where there appears to be darkness.

Mosse argues that while the word "surreal" is perhaps an accurate term for the infrared representation of the Congo, "as it exists beneath realism (infra means below, beneath) … any reading must also take account of this particular colour infrared film's genesis as a military reconnaissance / aerial surveillance technology, an essentially western technology developed to fight a kind of warfare that is fundamentally scientific, which operates on the premise of "knowledge is power" (first instance of this idea was in Hobbes), a technology developed specifically for the gathering of intelligence."

He writes, also, of the discoveries he made of his abilities, and where his attention took him as a photographer:

One of the great surprises of my work in Congo was the discovery of my own interest in portrait photography, which I had never previously attempted. There was something about making portraits of rebels in eastern Congo in which the subject seemed very clearly to resist the camera's objectification. Making portraits of these people was often a sort of face-off confrontation, in which the subject (not just rebels, but also villagers) seems clearly violated by the lens at the same moment that they adjust their posture to pose for the photograph. I found this resistance fascinating, as it seemed to highlight the subject-object relation of photographer and photographed. There's a certain vulnerability revealed by the subject's stony defiance of the camera's gaze in images such as General Fevrier or Tutsi town, which I feel only serves to emphasize the authorial hand, and its objectification of the other, like a European child pointing his finger at a black man in a provincial German supermarket (something I witnessed last week).

Whatever Mosse comments upon is arrived at through the picturesque nature of the infra images, and observer's engagement with the subtleties carried within the beauty of the photographs. While many other war photographers direct the world's attention to the spectacular moments of a conflict, collective grief for lives lost, or the massive aftermath of damage to structures, Mosse's images capture what appears to be a near peaceful aftermath – the lonely remainders of domination and fear. The images contain little of the aggrandisation of aggression, even when the soldiers pose and posture; instead, as A.H. Huber explains, the use of Aerochrome "makes vivid" the ways in which "cruelty can be sublime, and violence can ravage and remake a landscape in ways we may politically detest but also find visually arresting, even beautiful…[the photographs] arrest us as viewers, and in doing so interrupt our habits of perception." Huber argues further,

I think photographs always simplify and falsify the world they show us, but Mosse's Congo photographs also expose something of the instability and contingency of our perception. And yes, in this way Mosse keeps faith with a kind of queer critique, the hallmark of which is the impulse to make the power of objective claims visible: What is real, and who decides? The stakes are high when we are dealing with histories of violence, where one never knows if the devil of disbelief might outshout the devil of indifference.

When I first read Huber's analysis of how Mosse maintains "faith with a kind of queer critique," I couldn't let go of that idea. What does it mean to "queer" something? How does that upset/reconfigure – beginning with sexuality/gender, but in other arenas, too? William B. Turner, in A Genealogy of Queer Theory writes that queer theory emerged out of feminist theory and critical theory, "with a focus on the investigation of foundational, seemingly indisputable concepts, particularly with an eye to tracing the historical development of those concepts and their contributions of 'sex' and 'gender' such that the differences of power along those axes of identity pervade our culture at a level that resists fulsomely the ministrations of political action conventionally defined" (Temple University Press, Philadelphia, 2000, p. 3).

My Theory Uncle in Denver, Colorado adds, "At its most banal level, queer theory would interrogate what constitutes a picnic and what are the threads of identity, power, representation, gender, and sexual practice / identity that constitutes a picnic. And maybe that wouldn't be so banal after all," because, as a tool to interrogate the axes of power, desire, identity, gender, sexual practice, representation and sexual identity, Queer Theory helps us ask seminal questions about "how certain forms of difference become acceptable bases for the most violent expressions of prejudice while others do not," or, "In other words, what sorts of differences matter?"(2).

It is that desire to investigate "seemingly indisputable concepts," tracing "the differences in power" which allows Queer Theory to "resist fulsomely" conventional definitions. Mosse was also able to latch on to the idea that both technique and technology would permit a revelation of conventions; in fact, he understood, instinctively, that a technology meant to harrow into shadow spaces, revealing all that one deliberately secrets away, could, instead, expose the closeted anxieties of the looker.

One of the troubling aspects of his journey as a photographer has been the upset his infrared work causes, offending "sensibilities on both sides of the spectrum," writes Mosse. First, "dyed-in-the-wool reportage photographers," the old guard of photojournalism, often seem to find the infrared colour palette in this work to be a flagrant violation of the "rules of photojournalism." Certain war photographers "dismiss the work outright," which makes Mosse wonder whether they are simply busy with "the guardianship of realism." Along with the umbrage caused to the traditions of photojournalism, he also runs into the issue of who should have the right to represent, "as if representation was territorial," and he were "trespassing," Moss writes. The question is whether a European man – and Irish man – can accurately speak for the Congolese. Certain discussions have "swiftly became heated and accusatory." He countered these heated questions by asking whether Steve McQueen may go to Belfast to make Hunger, "a film about "my" Irish troubles? Doesn't he know that only the Irish are allowed to represent the troubles?" Mosse counters that the territoriality surrounding representation of the Other is deeply problematic, precisely because such protestations do not take into account why "fresh opinions of [an] outsider's perspective might offer new ways to understand the old calcified clichés."

The essay by Adam Hochschild in Infra gives us the "just the facts" version of Congo's history, with the variations of history that most Americans do not like to incorporate as 'real' history; he begins with King Leopold of Belgium's early venture into making an area of land almost as big as the United States into his personal colony – and of Joseph Conrad's vivid, and memorable account of the unspeakable 'horror' he encountered, five years into Leopold's ravages. We also learn about how the Belgian government, realising that the decimated population could no longer produce as desired by their colonial master, gave the Congolese better health care and educations – but not too much education. So controlled was the level of knowledge permitted by Begium that by the time of independence, there were no Congolese "trained as engineers, agronomists, doctors, or army officers. Of some five-thousand management level positions in the civil service, only three were filled by Africans." The U.S. is not simply implicated, but indicted: "Less than two months after the new prime minister [Patrice Lumumba] took power, U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower ordered the CIA to have him assassinated," and then, proceeded to ensure that the U.S.'s "investments were protected" by a billion-dollar system of aid that only served to maintain their ally, Mobutu Sese Seko.

Next to (and together) with Hochschild's, Mosse's own narrative is deeply illuminating: some of the things that I felt conflicted about, as I looked at his photographs for the first time in the British newspaper, The Guardian, are explored here. He approaches, with honesty, what it means to arrive as an outsider to Congo, and to continue to be a reincarnation of "Marlow": without the adequate means of comprehending the visual and linguistic signs, then turning to the surreal as a possibility. While Hochschild's words provides a sort of reassurance – yes, this wordless horror, too, is representable – Mosse's exploration admits to succumbing to the classical Conradian "horror" initially, and the wordlessness of encountering all that we regard as Other: the inhuman, the pointlessness of such abject brutality and suffering, and the lack of clear binaries and possible solutions.

Like more illustrious scholars like Chinua Achebe, I have also made it my business to critique the "preposterous and perverse arrogance in thus reducing Africa to the role of props for the break-up of one petty European mind," wherein Africa is used "as setting and backdrop…as a metaphysical battlefield devoid of all recognizable humanity, into which the wandering European enters at his peril…[thusly] eliminate[ing] the African as human factor." In Achebe's seminal critique of Conrad (and the general European inability to word Africa and the African), he does not have a problem with European ambivalence towards the colonising mission and the colonial officers' aversion to their own "civilisation." His quarrel is, in actuality, with those who attempt to resolve this discomfort by removing Africans of their full and complex humanity. I, and other critics after Achebe have suspected that for Conrad and his narrator, the wordless horror he experienced was more of an indication of internal processes concerning the havoc he saw, in which he now recognises himself as a small tool – the root of which was intimately tied to consumption and amalgamation of power over supply. Projecting that horror on to the Other has been a part of a long tradition of European (and probably others') conquest.

In Mosse's photography, what I note is the possibility of re-visioning that which appears to be horror/wordless. So it's almost as if we need to have it "queered" in order to see anything in a morass of signals. The infra-work draws attention to the Otherness, and removes difference at the same time without succumbing to a cheesy sort of "We are the World" mirroring technique. Here, we have to live within the grey (or the pink) of simultaneously recognising the impossibility/Otherness of this place, and actually seeing the human actions there, doing things in a very logical fashion.

Mosse writes, in an email communiqué, that he is "particularly drawn to these ideas of 'the wordless horror' that I identified in Marlow. He directs me to Elaine Scarry's The Body in Pain for an elaboration on the prelinguistic, guttural failure to communicate the experiences of pain. For Mosse, these verbal failures are related to the "abject failure of the dumb optic of photography to describe a complex conflict situation…this failure was most acute when photographing the pastoral landscape of Tutsi highlands [recreated in the eastern Congo], the cattle at dusk, which makes only for beautiful and seemingly reassuring and peaceful imagery but should in fact speak volumes about the land conflict currently unfolding, the deforestation, the poisoning of primeval jungle, and the destructive encroachment of Rwandan pastoralists onto a Congolese landscape." This litany of disparities "between what the lens reveals, or is able to say, and what is actually at stake" is what Mosse identifies as the "problem with my own technique, the procrustean aspect of Kodachrome, which I seek to violate."

One can speak easily in clichés about infrared images: how seeing something in infrared light conjures up the magical ability to see the familiar as Other, making the obvious into the uncanny. Under the manufactured surrealism created by Aerochrome, everything we see is near bubble-gum delightful – grotesquely so. Here, conflict over the right to dominate over land, mineral rights, and access to sex is washed over by waves of unexpected rose, splotches of scarlet. But there's something more aesthetically electrifying within Mosse's images, beyond the shock of seeing rolling, terraced hillsides as flawless as those Sri Lankan tea-growing highlands with which I am familiar, snaking turquoise rivers, human encampments surrounded by the abundance of banana leaves, and machine-gun-toting soldiers who appear to be clad in campy pink fatigues. We begin by imagining that darkness to be in the external location of the geographical and psychosocial world that is Congo; but soon enough, as Conrad himself recognized on his famous fictional journey down the great river, that darkness is ours, rather than an external manifestation of horror.

* Richard Mosse's "Infra" is showing November 17 – December 22, 2011 at the Jack Shainman Gallery in New York City.

November 20, 2011

Paris is a Continent, N°3

Number three in this series.

On "Avec le sourire" (off his new album C'est Correct"–out November 14th) and over a sweet rhythm L'Algerino (you get his name) calls out far right French politician Marie le Pen. The youth movement of the Front National is not amused of course.

Last week I featured "force et honneur," the first single of rapper Nessbeal's new album "Sélection Naturelle" (out tomorrow). This week, here is "Soldat."

Mister You and Colonel Reyel continue the black-Arab alliance over playstation and an apartment filled with beautiful people:

Finally, one of my favorites Corneille with "Des peres, des hommes et des frères" (fathers, men and brothers), featuring who else but La Fouine. (You'll remember La Fouine from last week. He just won best French artist at the MTV Europe Music Awards 2011 held in Belfast. (He was up against David Guetta, Martin Solveig, Soprano and Ben l'oncle Soul.) La Fouine has finally been crowned French artist of the year.)

* Hinda Talhaoui is also known as Sean's "French-Algerian connection." Hinda grew up in Paris and now lives in New York City. She mines the playlists of her friends back home.

Paris a Continent, N°3

Number three in this series.

On "Avec le sourire" (off his new album C'est Correct"–out November 14th) and over a sweet rhythm L'Algerino (you get his name) calls out far right French politician Marie le Pen. The youth movement of the Front National is not amused of course.

Last week I featured "force et honneur," the first single of rapper Nessbeal's new album "Sélection Naturelle" (out tomorrow). This week, here is "Soldat."

Mister You and Colonel Reyel continue the black-Arab alliance over playstation and an apartment filled with beautiful people:

Finally, one of my favorites Corneille with "Des peres, des hommes et des frères" (fathers, men and brothers), featuring who else but La Fouine. (You'll remember La Fouine from last week. He just won best French artist at the MTV Europe Music Awards 2011 held in Belfast. (He was up against David Guetta, Martin Solveig, Soprano, Lady Gaga and Ben l'oncle Soul.) La Fouine has finally been crowned French artist of the year.)

* Hinda Talhaoui is also known as Sean's "French-Algerian connection." Hinda grew up in Paris and now lives in New York City. She mines the playlists of her friends back home.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers