Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 587

November 30, 2011

New Clothes

Africa and contemporary art

Blogger and broadcaster Mikko Kapanen visited the ARS11 exhibit of contemporary African art in Helsinki. These are his images and impressions written for AIAC:

I am no contemporary art expert. Sometimes one has to start with a disclaimer. The term and whatever definition whoever gives to it have been on that awkward zone where I have felt that I should be equipped with more specific knowledge to say even something quite generic about it. Also, my intuitive and somewhat outdated direct connection between the idea of contemporary and fine art has always had this self-manufactured inner conflict with my identity relating to counter culture. Even if the conflict wouldn't really exist, I have imagined it. I think I have been quite elitist in avoiding certain kinds of art, so I found myself rethinking a few things as I was going to see ARS 11 exhibition in the Kiasma museum of contemporary art in Helsinki, Finland. This year the tag line promised that the exhibition "changes your perception of Africa and contemporary art".

Of course, first I had to figure out what exactly is my–let alone everyone else's–perception of Africa. Isn't it false-advertising to promise to change something that you can't universally define and which varies from individual to individual? The use of this misguided slogan is hardly the fault of the many artists featured in the exhibition, so I thought, for my benefit and just in general, let me have an open mind. Perhaps that is the prerequisite for art anyway.

The museum is bang in the city centre overlooking the brand new state of the art music house (also, regardless of the official version, built largely for the purposes of fine art) and the nine tents of Occupy Helsinki that are standing in the rain next to it. It's all very Global Village.

My experience of the art was pretty much as I expected; some works were great, some not to my liking which is understandable considering the quantity of art in this exhibition, but admittedly, very little of it did much to change my perspective of the African continent and cultures. I don't know if it did more to someone else. Generally speaking a lot of recycled materials had been used and waste was a recurring theme that was approached from many angles. A lot of beautiful photography (some examples of my favourites were Samuel Fosso, Kudzanai Chiurai and Maïmouna Patrizia Guerresi), various installations and sculptures were scattered around the five floors of Kiasma.

For me, by far, the most interesting parts of the exhibition were the work of Nigerian photographer J.D. 'Okhai Ojeikere and South African artists Mary Sibande.

Ojeikere's photography collection titled 'Moments of Beauty' consisted of beautiful black and white images recording the Nigerian history. I found it interesting that in an exhibition that is supposed to change my view of something, the items I most enjoy, and which I think may work the best in delivering the promise of performance the curator has made, are the ones that are not abstract at all. It is just straightforward snapshots of real events in history. If reality changes our perspective, then what is our perspective based on to begin with?

Mary Sibande's art had more layers. She is playing with the idea of South African (and perhaps beyond) maids and their role in society. There were some beautiful photographs, but the piece that really stole the show was a large dressed up statue of a maid wearing a Victorian style royal blue dress riding a stallion reaching to the sky (my image below). Whether by design or by accident this horse riding maid was separated only by a window from the native horse riding statue of the Finnish war marshal and former president C.G Mannerheim (see in the background). Next to each other, quietly they ooze thousands of meanings from different struggles; one from the top of his local food chain and the other from the bottom of her own. Yet, and this might be largely due to my own values and interpretations of history, the one on the inside, the maid, was the one whose horse was to ride her to triumph, even a modest one if such an expression exists, as the historical narrative becomes less Euro-centric.

I still see Africa as I did before this show, but I enjoyed much of the art. Perhaps the exhibition mainly changed my idea of contemporary art which it also promised to do. So that's okay, but if this exhibition really changed the perceptions of its viewers on Africa, I think we should move to an area that is closer to my main interest and ask why–and media I am looking at you now–is it that these works would change the way anyone sees a continent that is frequently in the news? Perhaps there are more people than I'd care to imagine who view the whole continent of Africa as 90% disaster zone with disease and corruption sprinkled over it desperately relying on the kindness of Bob Geldof and Bono, and on the other side, 10% safari game drive utopia with animals and poor, but smiling locals and Out of Africa settlers. If that was your idea, then perhaps it was high time for it to change.

The image problem that Africa has, to a large extent, is a result of the terrible geo-branding warfare by the global north which is an extension of colonial attitude that created the realities on the ground in the first place. If the low expectations that are in our midst change because of an art exhibition we shouldn't expect anyone to thank us, but rather we should say sorry this didn't happen sooner.

November 29, 2011

'See me on television' (in Lesotho)

From Maputsoe, Lesotho comes a new video for Kommanda Obbs's 'Hona Joale', recorded in the city of Maseru and on the Thaba Bosiu sandstone plateau (where the previous–under the rule of King Moshoeshoe in the nineteenth century–capital used to be). The chorus goes something like this: "I have been broke for a long time, standing on the corner, shooting dice. Right now I'm on form, I'm everywhere. See me on television…"

H/T (and translation): Ts'eliso

Egypt Elections

Egypt's parliamentary elections are underway despite the intense violence that has rocked the nation over the past few weeks. While we all watch and wait (and vote!), a friend reminded me of this song (originally by the legendary political musician Sheikh Imam) sung by Eskenderella, a popular Egyptian band. A rough translation of the lyrics (from a friend of a friend) is below the jump.

All the lovers unite in the castles prison, they unite in front of everyone.

The sun is a song in the prisons rising, Egypt is the song that is rising.

The lovers unite in the prison no matter how long they have to wait, no matter what happens, no matter how cruel the imprisoners are.

Who in his right mind can imprison Egypt?!

Unite while love is like a fire in your blood, fire that would burn hunger, tears and agony.

Fire that would cleanse your soul and take away our pain.

When we sell our self and souls to feed our children, when the lies that we eat does not suffice any longer. When the enemies foot is on our lands chest and lies made detectives live on my door step.

(Repeats *2)

And the detectives come like hungry dogs,

(Chorus)

they unite us lovers in prison now matter how long it takes or how matter we have to wait or no matter how cruel the imprisoners are. Who in his right mind can imprison Egypt?

Egypt is the song, the tears, the blood, the earth. Egypt is the reason we set out to squares (tahrir). Egypt is the sun that shines from the lovers prisons.

Rising and planting our hearts with gardens, Egypt is the gardens but who would collect the harvest.

He who will raise his sword to protect it.

(Chorus)

they unite us lovers in prison now matter how long it takes or how matter we have to wait or no matter how cruel the imprisoners are. Who in his right mind can imprison Egypt?

November 28, 2011

Music Break. Kouyaté-Neerman

We read that the balafon is being considered for inclusion on Unesco's Intangible Cultural Heritage list. Lansiné Kouyaté knows how to play it.

Congo Votes

"Instead of growing old with analysis, I dare to obstruct those who dream of paralyzing her." Congolese rapper Alesh calls out the country's politicians "qui concoctent dans le noir" [plotting in the shadows] and urges his fellow countrymen ("all heirs to Patrice Lumumba") to wake up.

Over the past week, it was hard to find an article published in a major international press outlet not looking at the build-up to today's presidential elections through the lens of fear and/of violence. With the exception of a few, most foreign journalists didn't make it outside of Kinshasa (citing logistical problems). People did get killed in the Congolese capital on Saturday, and in Lubumbashi today, but the way this violence creeped into the international headlines mars the calm and smoothness of the election process in other parts of the countries, as reported by Congolese citizen journalists on their blogs, in their local papers, or on their facebook pages. Congo is more than two cities.

For reports by local journalists outside Kinshasa, read Now AfriCAN (North Kivu), Local Voices (Bunyakiri, South Kivu), Mutaani FM (also in Kivu), Radio Okapi (MONUSCO's website and radio channel) and Le Congo. (If you want images and reports from Kinshasa other than the foreign ones, there is Lingala Facile.) And when the votes have been counted by the end of the week, refocus on what's happening outside the Congolese political theatre. Change won't come from the government. As most Congolese realized a long time ago. Ask Alesh.

The afterlife of African studio photography

Is African studio photography, Cape Town art writer Sean O'Toole asks in frieze magazine, dying out? The answer, non-subscribers, is maybe. Everywhere in the modern world the business of professional photography is in decline. O'Tool argues that studio photography has suffered the economies of the 'digital revolution' and the rise of the mobile phone camera. According to him the easy publishing of social networking sites has dealt a death blow to the popular African institution.

Studio photography has been the medium of many of Africa's most internationally renowned artists. Malick Sidibé's (b. 1935) joyful shots of independent Mali, are celebrated in this year's Paris Photo and the ninth biennale in his native Bamako. Similarly, the virtuosic monochrome portraits of Seydou Keïta (1921-2001) have gathered acclaim since his first exhibition in Paris in 1994. The two Malian photographers are often coupled together in indexes of African photography, but there is an critical distinction between their practices. Sidibé went onto the streets of Bamako, and used his talents for reportage. In 1962, two years after Independence, Keïta was nominated official photographer of the single-party socialist state. In a 2008 interview with lensculture, Sidibé spoke about Keïta:

People showed me his photos, but I didn't go to his studio. Many things prevented me from going to Seydou's. With my notoriety from reporting, going to Seydou's studio … They all had it in their minds I might put a spell on them, or something like that, to make them lose customers, so I never went to the studio. … It was Seydou who came to me to bring cameras to be repaired. Back then, Seydou had almost finished at his studio. He was now working for the government, taking ID photos of prisoners, and so on. So I did not go to Seydou's studio. No.

Sidibé is clearly troubled by the medium they share, and tries to establish distance between his work and Keïta's along the lines of professoinalism and politics. The spirit of radical dissidence inhabits Sidibé's work, which is difficult to place into the categories of the professional photographer. This art is haunted by the camera's availability as a tool for state control.

Photography has always been deeply involved with politics. Early photographs which celebrated the brief life of the 1870 Paris Commune were later used to identify and prosecute the communards. In the first scene of Athol Fugard's monumental play, Siswe Bansi is dead, a man arrives at a studio in provincial South Africa to have a photograph taken. It is, he says, to send his wife in the country. The play shifts back in time and it transpires that this man is Siswe Bansi, on the run from the police. Bansi and a friend discover a dead man in an alleyway and decide Bansi should steal his identity. The play ends back at the beginning, and Bansi is photographed for his new identity papers. In this studio, photographs are not only taken for personal portraits but passport photography, and the camera is as much an apparatus of state control as a joyful commemoration of life. At the end of the play, Siswe Bansi is dead and the photograph is the document which tells his wife he is still alive; the photograph is a technology which wakes the dead, and kills the living.

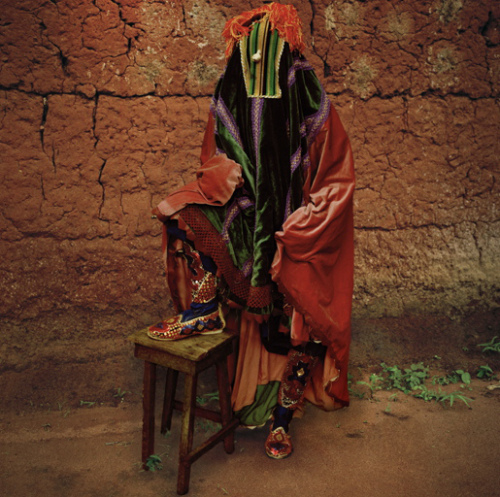

The young career of Leonce Raphael Agbodjelou (b. 1965), whose work is currently on display at the Jack Bell gallery in London, makes an interesting engagement with the traditions of studio photography. A year ago Agbodjelou was making work which looks unexceptional against the backdrop of post-modern African image-making: grinning men wearing sunglasses and brightly coloured clothing pose against patterned wallpaper. It is clear that the subjects of these photographs are their maker's clients. Agbodjelou learnt the trade from his father, Joseph Moise Agbodjelou (1912-2000), a photographer well-known in and outside of his native Benin. A small picture by Joseph Agbodjelou sits opposite these smiling men. In this a woman poses in front of a torn studio backdrop which hardly covers the bare wall of the building behind. Leonce Agbodjelou's most recent series, the Engungun Project, represents a return to these stark and humble beginnings.

The Engungun are masqueraders in the Yoruba traditions of Benin and southern Nigeria who ritually cleanse the local community. The actors wear costumes made out of furs, found fabrics, imitation shells and sequins, designed to adorn the motion of their performance. As Charles Gore's exhibition notes explain, these figures embody 'both named and unnamed' ancestors, which often 'vary from recent deceased and historical forbears, to acting as community executioners of criminals and witches'. No one in the community is permitted to know who the actors are; they become the walking dead.

The project of gathering these images was not an unpolitical act: Agbodjelou was sent home from one trip to southern Nigeria by the police, threatened by the presence of his camera. The exhibition notes also mention recent threats to the Engungun traditions:

the rise of Pentecostal churches in the 1990's across West Africa [presented] a new challenge to Engungun masquerade … as these churches sought to demonise indigenous religions (and their pantheons of deities) as pagan and dangerous and, as such, to be vehemently rejected. Engungun has responded in elaborating a counter-narrative of localised Yoruba memories, personalised histories and ritual through public performance that upholds the ethical values of the community.

The photographs displayed in the gallery are not labelled, and the viewer is thus denied even their subjects' namelessness. The streets and rural areas in which the figures are placed are carefully lit to highlight the texture of this studio en plein air. The intended effect of this project is, it seems, not to catalogue this spectacle with an ethnographic lens, but to make its curious spirit manifest.

[one more picture from exhibit]

The thesis of O'Toole's article, that non-specialist publishing on social networking sites endangers the life of African studio photography, demands further thought. The claim recalls a belief, after the invention of the daguerrotype, that painting would become obsolete. Photography did not murder painting, which responded with Impressionism and the birth of a revolutionary avant-garde. It is apparently one of modern art's most cherished lies to declare a medium bankrupt in order that the next generation of artists inherit the task of reinventing it. O'Toole refers to the work of Cheik Diallo, Santu Mofokeng and Kwame Apagya as exponents of an art-form which is not so much artistically dead, as financially defunct. This argument does not consider the crucial distinction between photography as art and as business. The significance of vocation is concretely proven in Bamako. Seydou Keïta retired in 1977 at the age of 56. O'Toole notes that this was "around the time 'colour photography took over' and machines started doing the work". As it turned out, colour film did not bring about the end of art photography but has contributed to its expansion. Malick Sidibé still practices in the studio he established in 1958.

Commentators have often warned of the vulnerability of social networking to abuse by governments and corporations. There are not many countries in which political dissidents may use the internet without some fear of supervision. It is important that photography – in digital and film, in the street and in the studio, on websites and gallery walls – negate the camera's use as an apparatus of state power and corporate interests. It is difficult to predict how social networking will influence art in the future, but the photographers whose vocation it is to document life in Africa will without doubt continue to confront the politics of image-making with energy and self-consciousness. There is hope within the ethical ambivalence of photography; a camera in certain hands becomes the weapon that disarms itself. Joseph Beuys recognised the same when he called for art to heal the knife that cuts the wound. Leonce Agbodjelou's odd, faceless images are useful reminders that some things may be photographed but not captured.

The Belfast Connection

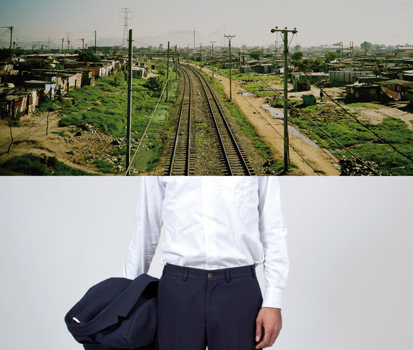

I interviewed the Northern Irish filmmaker Phil Harrison (credit: "Even Gods"), who is crowd-funding his first feature, "The Good Man," set in Ireland and South Africa. The film tells the stories "of a young banker in Belfast and a teenager living in a Cape Town township. When their lives unexpectedly collide, their impact on one another is far greater, and more surprising, than either could have imagined." Phil, writes: "In terms of the stage we are at we have almost reached our corwdsourcing target–there's less than 50 shares left of the 400 total." If you want to support the film, by becoming a shareholder, click here. Some production notes: The actor Aiden Gillen (credits: The Wire–he played Baltimore's Mayor Carcetti– and Game of Thrones) has signed on to play the lead. Here's our email interview:

Can you tell us how you came to make the connections between South Africa and Northern Ireland which to some may not be that obvious?

I'm from Belfast. In my early twenties I did what a lot of white Westerners do, and volunteered in an orphanage in South Africa's Kwazulu-Natal province, just outside the city of Pietermaritzburg. I was struck, even at the time, by the problematic nature of 'charitable' involvement by westerners like myself, engaging with the 'problems of Africa'–oversimplification, naivete (on my part), a fundamental failure to engage with or even understand the political nature of people's lives and struggles.

I was subsequently involved in various community development projects back in Ireland, and became increasingly interested in the role of creativity in protest and struggle: how people use photography, poetry, film, music to articulate ideas of identity which move away from and subvert those foisted on them – this is certainly true where I grew up, in Belfast, and I began, after doing a Masters degree in postcolonial literature and theology, to explore this in an African context. I spent a bit of time traveling in Sub-Saharan Africa in 2007–Malawi, Tanzania, Mozambique, South Africa, Ghana–just meeting artists, writers, musicians, filmmakers, and reading the histories of the likes of Seydou Keita, Djibril Diop Mambety, Lewis Nkosi, Frantz Fanon; artists subtly (and occasionally not so subtly) playing with notions of identity and authority, and helping critically dismantle social patterns and languages of oppression. The idea for the film came very simply: to creatively bring together the two post-conflict societies I was most familiar with/interested in and see what would come out of the engagement.

You're working with the Western Cape Anti-Eviction Campaign in Cape Town. Can you more about that collaboration and how it came about and how it works?

When I first began exploring this idea, I was drawn to the organisations which make up the Poor People's Alliance in South Africa: Abahlali base Mjondolo, the Anti-Eviction Campaign, the Landless People's Movement, etcetera; organizations which represented, it seemed to me, much more of the truth of the new South Africa (in opposition to the 'Rainbow Nation' myth so easily thrown about). I was struck, when I spent 6 weeks in the country in 2007, how little had changed since my time there almost a decade before. Wealth seemed largely to be in the same hands, albeit with a small black elite gaining some access. I was struck by Michael MacDonald's analysis (in 'Why Race Matters in South Africa') that what the ANC had essentially achieved was political power at the expense of economic power–in the 'transformation' wealth and capital were largely untouched, despite white fears. But as Fanon had pointed out over thirty years prior, unless capital itself is restructured for the benefit of the many, a country has not experienced 'liberation'.

The Poor People's Alliance movements seemed the most articulate voice in all of this, the most prophetic–they were hugely under-resourced, but well organized and democratic. I moved to Cape Town in 2009 for the year and spent many months meeting with some AEC members in Gugulethu, who introduced me to many people in the area who told me their own stories and concerns. After a few months I chatted through the idea of a feature film with the AEC team – the idea was that I would write a fictional script based on what I had learned. Mncedisi (the chairperson) agreed to proofread the script and give a final okay, which was crucial in ensuring that the story stays true to the experiences and stories of the people I had met in the process.

How do you avoid that your South African location does not become background 'décor' for a story about injustice, interchangeable with any other place?

The film itself is rooted in Gugulethu, and we are employing people from the township in the crew and cast–both professional and non-professional actors, film students, etcetera. Extras will come from the areas within Gugs [how local residents refer to the area] in which we're filming. The stories within the narrative all reflect genuine stories and experiences I encountered there. There is a real sense, of course, that these experiences are universal–the lack of adequate housing, the fear of crime, the failure to deliver on the promises of transformation. Good storytelling, I feel, always walks that line, where the particular stands in for the universal–but the stories have come directly from the streets where we are filming, rather than being imposed from the outside.

At the heart of the film is the question: "What does it mean to be good?" On the film's website you've written that it "is a simple question without a simple answer." Do you think you closer to that answer?

No. If anything, the question breaks down into more questions, about language, about intention, about capitalism. What can a phrase like 'goodness' mean in a system which is fundamentally amoral? In the current critique of banker's greed, the bailout, etc, I think it's vital to explore the underlying rationale of 'the market'. The 'system' is not just a set of financial and political structures, but a series of underlying assumptions, ideologies. And as Slavoj Zizek points out, ideology is at its most powerful when it appears invisible, 'normal'. In a small way the film is trying to wrestle with some of this stuff, albeit non-didactically and without proposing simple solutions.

How does your approach break with films on and about South Africa. I detect a critique of what passes for the film industry in Cape Town and, in some senses, a South African film industry?

I guess we're trying to do this at two levels. Firstly is the story we're telling; not a rosy-hued 'rainbow nation' version of South Africa, a la 'Invictus', but one where, for very many people – maybe over half the population–transformation has not really worked. And secondly, by involving local people/filmmakers in the actual process. The film industry in Cape Town is still very white, and heavily indebted to the commercials industry; young, black filmmakers struggle for opportunities in this context. It sometimes seems that to achieve anything you have to get sponsored by a sneaker brand or a beer company. We are building a crew with young, talented filmmakers from Gugulethu/Langa etc, and aim to help everyone involved step up a level in terms of skills and experience. We have also built a financial model to ensure that returns from the film also flow back into the places where we're filming. 10% of any return worldwide goes back to filmmakers/artists/activists in the townships.

Irish investors–more from south of the border–are heavily involved in the construction of luxury apartments in Cape Town and in changing the city, making it glitzy but also more unequal? How does that play into your script? Are people in Belfast or Dublin even aware of the Irish presence in South Africa?

I would say most people are unaware of the Irish construction presence in South Africa. And that presence is wide-ranging, from Habitat-style building projects which are actually spoken of very highly by many people I came across, to the high-end glitzy hotel-type development projects. The presence of western companies in South Africa is something the film explores, though I'm not going to give away just how. But it is a clearly a vital component of how we are connected – how the money from my savings or bank account in Belfast impacts communities thousands of miles away, often in surprising and problematic ways.

* Images: Courtesy of Phil Harrison.

November 26, 2011

Paris is a Continent, N°4

By Hinda Talhaoui

It's the return of one of the best R&B artists in French. K-Reen is back with a new track called "Like Before" featuring rapper Youssoupha. Her album of should be out in March 2012. And here's a link to a clip of an acoustic version of the song:

More Nessbeal. From his new album, the song "La Nébuleuse des Aigles" featuring his discovery Isleym (remember her):

Somebody new in this column: Mac Tyer. The video for the track "Docteur So":

November 25, 2011

I remember Black Pete*

As a child, I never believed in Santa Claus.

I believed in Saint Nicholas and Zwarte Piet (Black Pete). I remember waking up as a child on December 6, 1983, three hours before daybreak. I also remember waking up early on December 6 for years afterwards. Always early, always too excited to go back to sleep the night Saint Nicholas came by our house. Over the years, I got to share this rush of euphoric anxiety with my two younger brothers. We would be jumping on our beds, calling our parents, yelling out to ask whether it was time yet. They were never amused. My brothers and I knew there was no way we could pussyfoot downstairs into the living room to see which presents He had left us. Because each year, Saint Nicholas's black servants, those sneaky Black Petes ('Zwarte Pieten') would have locked the room's door on their way out. My parents held its only key.

You know Black Pete?

I remember sitting in our classroom when there was a sudden banging on the window. I would first see a pair of gloved hands throwing candies against the glass. Next thing we knew, the classroom's door would be flung open, and in stormed two Black Petes, spraying the floor with marzipan cookies. We all dove under our desks, grabbing as many sweets as we could fill our mouths with. The Black Petes then ordered us to follow them. We rushed out in total chaos: there's no way the teacher could hold us back.

Although he was a ubiquitous feature in my childhood, in 2011, Black Pete stands in the docks, again, charged of blackface, and all the attendant racism attached to cultures that employ this form of costumery to evoke what they imagine to be attached to 'blackness'. Why, Black Pete's accusers ask, can we possible be tolerant toward the annual dressing up by men and women alike as curly haired, black-faced, red-lipped servants to a holy white man? Why do people in the Netherlands allow for this ritual to continue? A ritual that so bluntly flies into the face of anybody who finds the staging offensive, who considers the practice despicable; a yearly, publicly accepted rehashing of colonial stereotypes?

I remember standing in the school yard: we're watching the Black Petes, sometimes in awe of their acrobatic skills, more often laughing at their silliness. We're waiting for Saint Nicholas to arrive on his white horse. He's visiting our school! We sing. The Black Petes urge us to sing louder: "He won't come, if He can't hear you!" We sing with even more zeal: "Please, Saint Nicholas, do come in with your servant, because we're all sitting upright / Maybe you have some time for us, before you ride back to Spain." (Saint Nicholas lives in Spain, Santa in the North Pole.)

Little did I know, back in the eighties, that already there were early attempts to get rid of this figure. The first official protest on record is by a woman named M.C. Grünbauer who, in 1968, thought "it no longer appropriate to continue to celebrate our dear old Saint Nicholas feast in its actual form." While slavery has been abolished for over a century, she says, "we continue the tradition of presenting the black man as a slave. The powerful White Master sits on his horse or throne. Pete has to walk or carry the heavy sacks."

Since the 1980s, historian John Helsloot reminds us (that's him doing the soul-searching in the video above), it is mostly black people who try to convince the Netherlands of the offensiveness of the figure of Black Pete. Young Surinamese who emigrated to the Netherlands in those years, carrying with them the discrimination by white Dutch colonials in their home country, called out their former colonial masters over their racist ritual. Many temporary protest committees (varying from angry individuals to more organized groups) have lashed out at the practice ever since. Some of them were successful (up to the point where the Netherlands once experimented with introducing Red and Blue Petes–unfortunately, the Dutch public would have none of it), while the majority has silently disappeared from the stage.

I remember sitting in the school's sports hall, frantically trying to think of something I might have done wrong that year, when Saint Nicholas calls my name in front of the other school kids. There were hundreds of us. Uneasily but patiently, we all wait our turns. It made for long Friday afternoons and we loved every minute of it. But if I had done something bad, I would be punished. I would be put to shame in front of my friends. Worse, I wouldn't get my chocolate. And if I had done something really bad, Black Pete would put me in the bag he had slung over his shoulder, now void of all candy, and take me with him to Spain. It never happened. Fighting with your brothers turned out not bad enough a mischief. Nevertheless, I would hold on tightly to my candy, those afternoons, side-eyeing Black Pete.

Public attention (including a praised photo series by British photographer Anna Fox) and protests surrounding the Dutch obsession with maintaining this tradition of black caricature have come and gone over the years. So why would this year's protests be any different? Because earlier this month, one of those small protest groups –four people does constitute a group, one of them you remember as rapper Kno'Ledge Cesare– made it online and into the national media. Planning to peacefully rally wearing T-shirts with the printed slogan 'Black Pete is Racism' during the annual arrival of Saint Nicholas in the Dutch city of Dordrecht, they were caught off guard by the police, abused and their unrolled banner confiscated. They were also detained by the police.

The police should have thought twice, what with those cellphones around. It didn't take long for the images to surface on the web.

Online support for the claims of the detained group of protesters has grown since.

I concur.

Black Pete and St. Nicholas were so real to me that I remember asking myself what I would do, once in Spain, and released from the sack. And pondering how to make my way back home. But I also recall –in my third year of primary school, in that same sports hall– somebody I looked up to whispering into my ear: "He isn't real, you know."

That I'm writing this from Belgium–the Flemish speaking part of which has the exact same tradition; we share Holland's language, and some history–where there is no debate around the figure of Black Pete whatsoever proves we've got some work to do.

That there's not a peep against this caricature goes to show that here in Belgium, Black Pete (although we adults know that he's not 'real'), is very much alive. If the French, the Swiss, the Germans and the Austrians can have Saint Nicholas without Black Pete, why is it that we have so much trouble letting him go?

*The title of this post riffs off Denis Hirson's I Remember King Kong.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers