Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 585

December 7, 2011

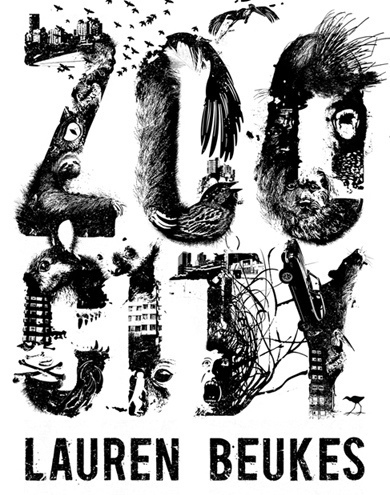

Zoo City to be turned into a film

Zoo City, the award-winning novel by South African Lauren Beukes, is to be turned into a film. Producer Helena Spring, also a South African, won the rights, and will be looking for a director.

Spring's credits range from the Oscar-nominated "Yesterday" and "Red Dust" (a not so good courtroom drama about the Truth and Reconciliation Commission) to the silly, but lucrative, Leon Schuster comedies Mama Jack (he's in blackface for most of the film) and Mr Bones. Her most recent film is "The First Grader", which is winning awards all over the place. So she seems to be in good company with Beukes, who earlier this year won the Arthur C Clarke award for Zoo City. The book also won a British Science Fiction Award for best art work – for designer Joey Hi-Fi. It is a great cover – far better in my view than the one on the North American edition.

Zoo City is a 'cyberpunk thriller' set in an alternate Johannesburg, where criminals or those who have serious moral failings, get landed with an animal familiar as a permanent attachment. They also get the added benefit of a psychic power. The book's protagonist is Zinzi December, a former journalist and drug addict, who ended up with a sloth on her back after causing her brother's death. She spends her time writing copy for 419 scam emails until she gets roped in to searching for a missing singer (her talent is being able to find lost things).

The concept of the animal familiar clearly owes a lot to Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials trilogy, although the idea plays out very differently.

Zoo City is incredibly innovative, and Beukes is clearly a really original voice in South African literature. She can be compared to China Mieville, another Arthur C Clarke award winner (in fact, here they are photographed together). They both write wildly innovative sci-fi/fantasy — Mieville calls his work weird fiction — set in dystopian urban environments. This kind of fantasy is very different from the escapist wizards and fairies you get in Tolkien and his clones. It's gritty and real, morally complex, and politically aware – though I think Beukes is not yet quite at Mieville's level.

I enjoyed Zoo City, though for some reason about two thirds of the way through the book my interest started to flag. Despite the weirdness and invention of Beukes's language, context and characters, I found the storyline ultimately a little disappointing. I preferred her earlier novel, Moxyland, which I think deserves a lot more attention. The story of corporate and political power gone mad, and the use of technology for surveillance and control in a futuristic Cape Town, has powerful resonance in these days of Carrier IQ, Occupy Wall Street and the 99 percent.

December 6, 2011

Music Break. Exit feat. Gazza

Namibian rapper Exit and kwaito artist Gazza both live in the same street in Oshakati, so this collaboration for 'To Ti Ngaa' must have come effortlessly. You'll recognize the TransNamib Railway Museum in Windhoek — still a good ten hours drive from Oshakati though.

Jay-Z's Black Republicanism

Jay-Z's brand of Black Republicanism is now the subject of a sociology course at Georgetown University. Early insights: he "beat the system" and is "a businessman and a philanthropist who used to call himself a pimp." The professor is Michael Eric Dyson. I wonder how the course handles Jay Z's 'man of the people' posture, his t-shirt politics and his dubious pan-Africanism. And he gets compared to Homer, Melville, Toni Morrison, Langston Hughes, Martin Scorcese and Francis Ford Coppola.

DVD. 'Life, Above All'

Oliver Schmitz's South African AIDS drama, "Life, Above All," is now on sale on on DVD in the United States.

I was invited to a pre-screening of this film when it first came out this summer and would strongly recommend it.

"Life, Above All" is set in a small town in rural, religious South Africa. It tells the story of prodigious 12-year-old Chanda whose sister younger dies suddenly. Then her mother gets sick. AIDS stigma is widespread, so the family (and mom's close friend) hides her status from the neighbors. In the film no one wants to talk about "the disease." The film reflects the widespread AIDS denialism which for much of the 2000s infected South Africa as high up as the country's president. Chanda, though, refuses to shut up.

At the time "Life, Above All" was accompanied by a lot of good buzz: it was included in the 2010 Cannes film festival and Schmitz is probably the greatest South African director of his generation. His resume includes two gangster movies which came to define what passed for South African cinema in the 1980s ("Mapantsula") and the mid-1990s ("Hijack Stories")

My quick verdict: Don't be put off by the child hero (the film is based on a youth novel) or the slow pace. The film is ultimately rewarding. The young actress who plays the lead, Khomotso Manyaka, is excellent, and so is most of the supporting cast.

December 5, 2011

Music Break. Michael Kiwanuka

Brit-Ugandan singer Michael Kiwanuka (featured here before), who sounds like James Taylor, performs two of his songs — 'I'm Gettting Ready' and 'Tell Me A Tale' — on the British TV show, "Later with Jools Holland":

Beginning Workout

Translating Angola

By Megan Eardley

Rhett McNeil's translation of Portuguese novelist António Lobo Antunes's "The Splendor of Portugal" received a lot of attention from the literary world when it was released earlier this fall. And with good reason. McNeil has interpreted Lobo Antune's thick, cruel prose beautifully. But so far English-language critics have focused on the technical challenges of translating Antunes, as though they were somehow isolated from the text's socio-political and ethical questions. Overall, many of these critics miss the edge of McNeil's translation, which turns on Antunes's language in order to address the reproduction of colonial violence on a global scale. We might go further to question why certain kinds of war stories–such as Antunes's–are embraced by critics, and go on to find an international audience, while other finely written stories do not.

"The Splendor of Portugal" is a domestic drama that spans generations and ends with a once wealthy Portuguese family that has abandoned its plantation in the Angolan War of Independence (1961-1975). Now, the family that has made its way in the world cheating, lying, and stealing is caught out with all its secret affairs. The novel is structured by three parts, which can be roughly associated with vignettes of the family at the height of the colonial order, memories of the war, and the children's shameful return to Portugal. Along the way, ex-lovers and mean old grandmother press in with their most hurtful memories of alcoholism, sexual abuse, and racial violence.

The book's most explicit scenes highlight the connections McNeil has made between the violence of late European colonialism and the continuation of racial violence in English-speaking communities now.

Particularly provocative is his decision to translate the Portuguese racial slur 'escarumba' as 'nigger.' According to some Portuguese-speaking friends, 'escarumba' is not a word you would hear often in Lisbon today. It carries connotations of the racial grotesque of minstrel shows and might be translated through the condescending stereotypes of 'Little Black Sambo'.

McNeil's choice more boldly ties plantations in Angola to the transatlantic slave trade, and racial violence in America now. Like, 'the only time I ever heard her call him a nigger, the only time I truly understood that she hated him' (511).

Antunes lets the splendid Portuguese family self-destruct in its hatred. He is quiet as the mother explains what she has learned about 'Blacks':

that's the thing about the Bailundos that makes me furious, their expressions never changes, the police chief would raise his whip at them or hold their pistol up to their ear and there'd be silence, no complaints, they had no more awareness than inanimate objects, a childlike innocence that had nothing to do with pride or dignity or courage, I was going to say they had the temperament of a chicken, but chickens, good Lord, chickens at least kick their feet, try to escape, you see quite clearly that they're scared of us, but the Bailundos at most

">"Yes sir"

at most

"Yes boss"

never objecting, never revolting, apologizing for the inconvenience of making us punish them for no reason, just like when we go up to the whites in Lisbon (484).

Of course, 'the Blacks' do revolt and get their revenge. Lobo Antunes stays quiet and lets the reader imagine the mother's execution:

the pickup trucks parked next to the ditches, the dogs always returning with snouts low to the ground, whining, limping, the smell reached all the way to Luanda when the wind changed directions, the government troops wearing colored ties, mirror-lenses sunglasses with metal frames as if they were silver speaking of mirrors how long has it been flower-print suspenders holding up their military pants, the soldiers inviting me to get out of the pickup. "Ma'am" (534).

But Lobo Antunes' Black characters are foils that spend most of their time reacting to the complex and volatile Portuguese that he sets out to shame. His descriptions of the servants often really describe the family:

… for the first time I began to suspect that Maria da Boa Morte and I weren't equals, since my godmother hadn't called me a repulsive little black girl, hadn't looked at me with indignant disgust, I began to suspect that Maria da Boa Morte was somehow my inferior, she didn't have carpet or rugs just two or three straw mats, metal dinner plates that didn't match, a battery-operated radio with a broken antenna, and a doll presiding over all this wretchedness in its porcelain innocence (172).

When they are alone together, Lobo Antunes's Black characters are speechless, or at least inscrutable: "Josélia and Maria da Boa Morte made comments to each other without words" (432).

Critics might focus on Antunes's use of irony, wherein The Splendor of Portugal is read as a biting criticism of the Portuguese colonial project. But throughout 500 + pages of interior monologues, memories and self-recriminations, we never get to hear what they are thinking about. Haven't we seen Black people made dumb by the violence of White 'civilization' before? As the international literati continue to hold up brutal scenes of European colonialism as the best examples of literature from and about Africa, George Steiner's praise for Antunes as Conrad's rightful heir becomes a bit of a backhand compliment.

"The Splendor of Portugal" is beautifully wrought vitriol, well translated by Rhett McNeil. But I'd rather that we read it alongside talented Angolan contemporaries who are also working through the Portuguese language. Start with José Luandino Vieira's "Luanda" (translated by Tamara L. Bender), and some of Pepetela's "Mayombe" (translated by Michael Wolfers), "The Return of the Water Spirit" (Luis R. Mitras), Jaime Bunda's "Secret Agent" (Richard Bartlett) and José Eduardo Agualusa's "Creole," "The Book of Chameleons," "My Father's Wives" and "Rainy Season" (all translated by Daniel Hahn).

* Megan Eardley recently finished a postgraduate fellowship at SOAS studying Pentecostal media culture in Southern Africa.

Africa's best soccer football players are West African

On January 10 next year FIFA will announce its World XI 2011. The result, they remind us, will be based on voting by over 50,000 professional soccer players from around the world. "Every voting player selects one goalkeeper, four defenders, three midfielders and three strikers."

The 3-year-old award feels like another one of those endless FIFA awards created to showcase sponsors' products. But I'll take it.

The news is that FIFA just announced a shortlist of 55 players from which the final 11 players for the World XI 2011 will come from.

A quick "analysis" suggests no surprises:

The bulk of those shortlisted play for European clubs in three countries: Spain (18 players), England (17) and Italy (15);

The rest on the shortlist play either for German clubs (4) or in the French first division (1);

Real Madrid, Barcelona, Manchester United and Chelsea dominate the list with the most players;

Finally, Spain has 10 players on the shortlist, with the second largest national representation coming from the largest African country in South America, Brazil–with 9 players.

As for African countries on the continent: only four players made the shortlist:

Yaya Touré (Cote d'Ivoire and Manchester City);

Samuel Eto'o (Cameroon and Anzhi);

Didier Drogba (Cote d'Ivoire and Chelsea); and

Michael Essien (Ghana and Chelsea).

Of the four, only Touré, Drogba and Eto'o still regularly turn out for their respective national teams. Touré and Drogba will be in action at next year's African Nations Cup (ANC) in Equatorial Guinea and Gabon. Cameroon has not qualified for the ANC and Eto'o is the subject of a disciplinary procedure for leading a recent player revolt in the national team and is playing–bringing peace and cashing a huge paycheck–in the Russian league. Essien, who has been injured, hasn't played for Ghana in a while–he did not make the 2010 World Cup squad–though he recently expressed an interest in playing again for his country.

I was surprised at the omission of Kevin Prince Boateng, (Ghana and AC Milan) from the list. He is arguably the most exciting player of this generation of African players. (Boateng recently announced his retirement from international football.)

I am not sure if this poor showing is a sign of the poor health of African football. In fact, all four players left their homes early and are really products of European, mostly French, youth club systems.

But perhaps, we can agree on one thing with the world's professional players: the best African players come from West Africa.

The documentary imaginary

At the recent Film Africa film festival in London, the new Ethiopian feature film "Atletu" (The Athlete) was screened to a sold-out audience. Directed by Rasselas Lakew and Davey Frankel, it is a portrayal of Abebe Bikila, the Ethiopian runner who won two Olympic marathons in a row, and broke the world record in Rome in 1960, running bare feet. Here's the trailer:

The film follows a recent trend in feature filmmaking that weaves archival material with contemporary filmed footage, producing an interesting dialogue between the documentary imaginary and the fictional. The historical 'real', in these cases, don't just provide a narrative framework, or set-dressing aesthetic. They produce a filmic grain that in turn invests in the contemporary footage a sense of historicism and character. I'm thinking of Gus Van Sant's "Milk," where Sean Penn's portrayal of the first openly gay congressman Harvey Milk is bolstered by the warmth and nostalgia of the 1970s archival footage that is intercut throughout, or Shane Meadows's "This is England" (2006), where the opening credits show Margaret Thatcher in a tractor, or Princess Diana's wedding, or a scared bobby beset by women at the Greenham Common protests. It's an example of the use of archival footage to produce a setting that is spine-tinglingly nostalgic, so powerful in its evocation of a time past, that it transports you into it. The archival material is producing a social context, a milieu and an aesthetic that extends beyond the limits of staged scenes.

In the case of the Ethiopian film "The Athlete," the restrained, somewhat sparse pace is made possible by its borrowing of footage from Kon Ichikawa's momentous documentary "Tokyo Olympiad" (1965), which used 164 cameramen operating 1, 031 cameras to capture godlike athleticism interspersed with the true grit of physical determination and suffering. Here, below, follows the 9 minute marathon sequence from Kon Ichikawa's Tokyo Olympiad:

If "The Athlete" is a marathon-paced film on the whole — slow, restrained and rhythmic (the film seems to have 4 'chapters') — the use of archival material from Ichikawa's film are the cinematic sprints in time and narrative; they capture a sense of history, of Bikila's unending determination, and of a nations pride wrapped up in one thin, loping man.

Similarly, the images of Bikila running through a torch-lit Rome in 1960, the flourishing music disguising the (imagined) soft patter of his bare feet on the cobblestones is just as powerful.

Illuminated by the headlights of the motorbike filming him, or by the warm glow of the onlookers, Bikila seems to be running in a vacuum, running on an infinite stretch of moving road, with no particular destination.

After finishing the Tokyo marathon in 1964 Bikila famously said he could have run another 10 kilometres.

It is this unending determinism that "The Athlete" portrays; athleticism is not tied to a certain discipline, and there is no finish line, rather it is an infinite race with the self. When Bikila is injured in an accident, and tragically loses the use of his legs three years before his grand finale race at the Munich Olympics (in 1972), he continues to be an athlete, taking part in the Stoke Mandeville Archery tournament (near to where his rehabilitation hospital was located in Britain), and then in a cross-country sled race with the King of Norway.

But back to Kon Ichikawa's documentary: Bikila's godlike athleticism, his gentle, composed running style, perfectly symmetrical and ruthlessly resolute is celebrated by Ichikawa. As Bikila enters the Tokyo stadium for the final lap of his momentous marathon (watch the second embedded video, above, again), his loping body is caught delicately by a telephoto tracking shot. Slowed down, it exposes every sinew in Bikila's long and graceful legs, every muscle dancing to the rhythm of his feet on the track. This sequence of the film is truly remarkable for its deft admiration of the athlete's body, marvelling at the mechanics of its workings, revealing a photographic trope that revels in the capture of the exposed body (yet perhaps bears some uncomfortable link to colonial fascinations with the black body).

And yet, Ichikawa was not seeking the Man as God illusion that is shown in Reifenstahl's "Olympia" (1936). The camera does not elevate the athlete. Rather, Ichikawa's camera is close to the ground, zoomed in on the suffering, in the collapsed marathon runner, or in the beads of sweat dripping consistently from Bikila's chin. The athlete, in the archival footage and in Lakew's dramatisation of Bikila's life, is beyond everything, movingly human.

December 4, 2011

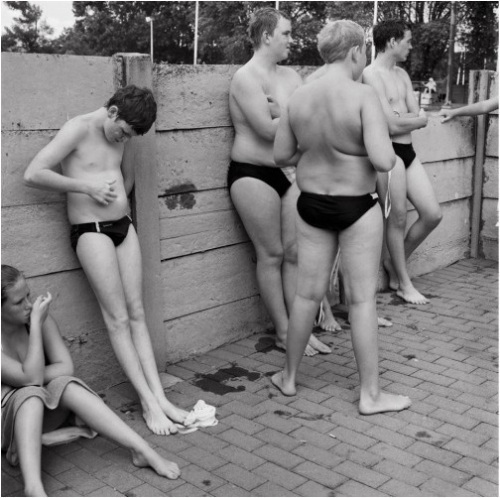

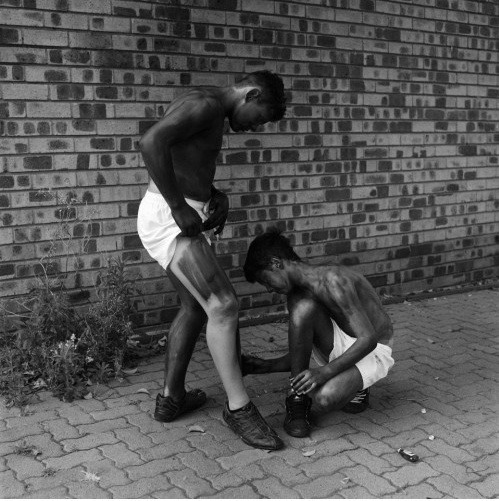

Brakpan

Brakpan is a declining mining town east of Johannesburg in South Africa. Photographer Marc Shoul's images of life there–mostly among the town's white inhabitants–has just won him first place in the Italian Winephoto 2011 photo competition. Here's some samples from the winning series:

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers