Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 565

February 9, 2012

What's wrong with abortion?

Is there a war on women's health care? Yes.

In the United States, the last week has seen one aspect of it, in explosive terms that continue to reverberate. Komen. Planned Parenthood. Abortion.

Abortion is but one front in the war on women's health in the United States. Maternal mortality. Shackling women prisoners in childbirth. Bad care. Abusive care. Refusal of care.

The war on women's health in the United States is a war without borders. So, let's talk about abortion and 'Africa', the continent … and the country. After all, the US Republican Party believes that "abortion is the leading cause of death in the black community."

And then of course there's Republican Representative Chris Smith who traveled 'all the way' to Kenya to make sure that the new Constitution, which bans abortion, wouldn't allow an exception, "abortions to preserve the health of the mother." Smith's African abortion adventure even caught the attention of … Africa Is a Country! One of the few times this site has mentioned abortion.

Last month, The Lancet published a Guttmacher Institute study, "Induced abortion: incidence and trends worldwide from 1995 to 2008." The findings were fairly widely publicized. For example, a leading Argentine paper commented on the findings just this week. In a nutshell, the study indicated that criminalizing abortion doesn't reduce its rate. It increases the rates as in so doing intensifies the dangers. The study provided little comfort, to put it mildly.

The altogether predictable dangers of illegal abortions are of particular consequence on the African continent. The study reports that of 6.4 million abortions carried out on the continent in 2008, only 3% were performed under safe conditions. In 2008, thirteen percent of all pregnancies in Africa ended in abortions. The World Health Organization estimates that in 2008 14% of maternal deaths were due to unsafe abortions. Ever year about 1.7 million women are hospitalized due to complications from unsafe abortions. The situation for women in rural areas is, again predictably, much worse, and much more intensely so. In 2008, 92% of women on the African continent lived in countries with restrictive abortion laws.

The somewhat happy outlier to this picture is South Africa. There, with the most liberal abortion laws and policies on the continent, the actual rate of abortion is the lowest … on the continent. There, with the most liberal abortion laws on the continent, abortion-related deaths dropped by 91% between 1994 and 2008. It's not perfect, by a long shot, but it's something.

Criminalizing abortion kills, maims and otherwise has harmed and continues to harm women across the continent.

So, how does abortion in Africa get covered? Most of the reports were general, covering the numbers, but two stand out for their 'case study' approach.

When the Guttmacher study came out, the BBC ran a human-interest sidebar, the testimony of Akech Ayimba, a Kenyan woman. Ayimba describes her life, her two abortions, her current work as a counselor to women who have had abortions. She also describes herself as, now, pro-life. The BBC focuses on her being 'pro-life.' The caption beneath her photo reads: "Akech Ayimba after her unsafe abortions now has a pro-life position." That's it. Nothing more. Ayimba's words speak of the difficulties, the pain, the questions, the arc of a life, but somehow the BBC reduces all of that to … "a pro-life position."

On the other hand, last Tuesday, the Christian Science Monitor reported on Isabel, a young woman in Mozambique. Isabel had an abortion at the age of 15. Abortion is illegal in Mozambique. Today, ten years later, she is 'one of the lucky ones'. She's alive. She's healthy, and she has a healthy child, who is five years old. In March, Mozambique will most likely vote through a liberalization of abortion policies, allowing for legal and voluntary abortions in the first twelve weeks of pregnancy.

The difference between the BBC case study and that of the Christian Science Monitor is one of focus. For Ayimba, as represented by the BBC, the crisis is seen among the survivors, the scars and syndromes. For Isabel, as represented by the Christian Science Monitor, the crisis is seen among the invisible, the women who died, who cannot speak for themselves.

Meanwhile, the world continues to produce global patterns of death from criminalized abortion. Yes, there is a war on women's health.

February 8, 2012

In Praise of Mohamed Aboutrika

By Karim Azeb, Guest Blogger*

It was 76 minutes and 41 seconds into the 2008 African Cup of Nations final match between Egypt and Cameroon when Mohamed Zidane beats defender Rigobert Song to the ball and squares across the goal to Mohamed Aboutrika who calmly maneuvers the ball beneath Cameroon's diving keeper to score the match-winning goal. This goal cemented Aboutrika's place as the 'superman' of Egypt's footballing history, was followed by his trademark celebration: dropping to his knees and touching his forehead to the ground in symbolic prayer. Aboutrika's exploits are also admired outside Egypt. In 2008, BBC readers named him African Footballer of the Year, and CAF named him (or shafted him as, depending on your point of view) to the 2nd best African player in their African Footballer of the Year selection (the same year Egypt and Al Ahly took National Team and Club of the Year, respectively). But Aboutrika is also a hero off the field.

Mohamed Aboutrika began his career at Tersana football club in Egypt's second division. In the middle of the 2003-2004 season, Aboutrika sealed a move to Egypt's most popular and most successful team in the midseason transfer window: Al Ahly. It is here that he began to build his reputation as Egypt's most talented player, scoring an incredible 11 goals in his first 13 games for Al Ahly.

On March 31, 2004, Aboutrika debuted for Egypt's national team against Trinidad & Tobago, scoring his first goal for the Pharaohs (the match ended in a 2-1 win for Egypt). In 2005 Aboutrika aided Al Ahly in claiming their first Egyptian League title in 4 years as well as the Confederation of African Football (CAF) Champions League title, which punched Al Ahly's ticket to the 2005 FIFA Club World Championship in Japan.

In 2006 Aboutrika led Al Ahly to a third consecutive league title, finishing the competition as the top scorer with 18 total goals. Aboutrika continued to dominate during the 2006 Africa Cup of Nations tournament, scoring important goals against Libya and Cote d'Ivoire in the group stages, setting up Amr Zaki's game-winning goal in the semi-finals against Senegal, and scoring the decisive 4th penalty in the championship game against Cote d'Ivoire. Al Ahly's victory in the 2006 CAF Champions league was highlighted by Aboutrika placing as the tournament's top scorer with 8 goals, which he followed up with the 2006 FIFA Club World Championship, also finishing the tournament as top scorer with 3 goals in 3 games.

To cap off his footballing achievements, Aboutrika led Al Ahly to four more league titles between 2007-2011 and helped Egypt complete an unprecedented hat trick of consecutive ACN championships in 2010. Ultimately, however, Aboutrika's achievements are not constrained to the football pitch in the minds of his fans.

In Egypt there is a popular story regarding Aboutrika's contract negotiations with Tersana. As the narrative goes, Tersana wanted Aboutrika and a teammate to sign new contracts and they offered Aboutrika a much higher salary than his teammate, but Aboutrika refused to believe he was more valuable than his teammate and insisted on taking the same salary as his teammate. Aboutrika, on the pitch and off, has been very conscious of his influence on Egyptian football fans, and signed with Tersana at the same salary as his teammates.

This story, like so many others of its kind, is what endears Aboutrika to the Egyptian people. He is not just a football hero, he is our hero. He plays football for the people, embodying Al Ahly's reputation as The People's Club. He refused approaches from European clubs so he could continue to play exclusively for the Egyptian people. He is a United Nations Development Programme Goodwill Ambassador and a World Food Programme Ambassador Against Hunger. When Aboutrika plays, Egypt stops everything to watch. When he speaks, the people listen. And when the people speak, Aboutrika listens. When they ask, he answers. He is a successful footballer, a devout Muslim, a generous philanthropist, a human rights advocate, and a supporter of Egypt's revolution.

Mohamed Aboutrika played for the club of the poor, the club of an independent and free Egypt, and now he plays – or, rather, does not play – for the people and their future. As February 1, 2012 will go down in Egypt's history as a day of national mourning following the deaths of 74 football fans in the devastating Port Said riot, February 2 will be remembered as the day Egypt's military rulers forced Aboutrika, our hero, to retire and help put the final nails in their own coffin.

*Karim Azeb is a college student majoring in History and Political Science and minoring in Afro-American Studies at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. He is also a fantastic football player and dedicated Ahlawy (and yes, Sophia is his big sister).

Y'En A Marre's political hip-hop anthems in Wolof

8 of 13 Senegalese opposition candidates trying to unseat Abdoulaye Wade in the upcoming presidential elections (including three former prime ministers under Wade, and no-longer-candidate Youssou N'Dour) gathered on Obelisk Square in Dakar last Sunday. The rally went peaceful, "crowds of color-coordinated supporters awaited while listening to political hip-hop anthems in Wolof." On Tuesday, Wade "tried to divert attention from growing street protests calling for his resignation and prove that he still had grassroots support by leading an impromptu rally through the capital," some hours after he summoned "the U.S. ambassador to Dakar" over the ambassador's telling local journalists that "President Wade has compromised the elections and threatened the security of the country by insisting on running for a third term in the February 26 presidential election" — a move in which "a lobbying group in Atlanta" had a hand. The anthems on Obelisk Square included the sound of Y'En A Marre.

The Toto 'Africa' Meme: Jason Derulo

R&b crooner Jason Derulo mouths some inane lyrics–complete with the "ba bum ba eh ba bum ba eh eh ba bum ba eh" refrain and acting out the "rain down in Africa" line in a shower–over synth beats. Toto taken to its logical extreme. I still think Karl Wolf still owns the R&B/dance adaptation corner of "Africa."

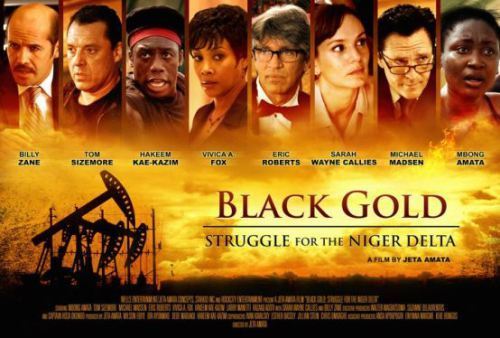

Nollywood and Hollywood

In a recent article in The Guardian, Phil Hoad writes that 'maverick' Nigerian director Jeta Amata is perhaps 'Nollywood's gift to Hollywood', for Amata's recent feature is a Hollywood-friendly big budget epic, delving into the horrific situation in the Niger Delta and the havoc that the oil industry leaves behind. Hoad's article is a nice survey of Amata's current status, yet it fails to truly explore how Nollywood could affect a wider cinematic context. Hoad is writing about Amata's upcoming feature Black November, a gritty epic of oil-fuelled conflict, collusion and unrest, which features an all-star cast, both from Hollywood and Nollywood (Billy Zane, Vivica Fox, Eric Roberts, Mickey Rourke, Kim Basinger, Anne Heche, Hakeen Kae-Kazim and Razaaq Adoti).

It has an impressively long synopsis on IMDB, and it tipped as 'hotly anticipated'. But why 'hotly anticipated'? In the same way that Blood Diamond — a teeth-grindingly banal look at conflict diamonds in Sierra Leone — was 'hotly anticipated' because it had DiCaprio in it, and the black darling of Hollywood, Djimon Hounsou? Invariably, when Hollywood deals with African conflict, political unrest or social issues, it produces a catalogue of stereotype, sentiment and sugary soundtracks. I'm thinking of recent offerings such as Machine Gun Preacher directed by Marc Forster and starring Gerard Butler, or The Bang Bang Club directed by Steven Silver starring Ryan Phillipe. Both are big Hollywood entertainment pieces that place white, courageous characters amongst the imagined chaos and freefall of African states, with none of the subtlety, sophistication or research that they might have dedicated to a film about a white conflict.

No, Black November is not hotly anticipated because it is a Nollywood director hitting the big time: it is because a Nollywood director has reached the dizzying heights of Hollywood, and all the famous names that come with it.

Rather than focusing on the instances where Nollywood directors/actors 'make it' in Hollywood (Amata's new feature is an American production), it is necessary to focus on moments where Nollywood cinema carves it's own, independent space within a Western context. At a recent forum discussing the trials and tribulations of securing theatrical distribution for African cinema in the UK, Moses Babatope spoke about his rise from Odeon usher to 'Odeon Cinema's special projects manager for Nollywood'. Moses managed to convince Odeon, one of the largest cinema chains in Europe, that Nollywood films deserve to be screened in their UK cinemas by running screen rentals, often showing Nollywood films at 11pm at night, which would sell out. Moses, a fan of Nollywood film himself was sure that there was a market, and the two films his programme has screened, Anchor Baby (2010) and Mirror Boy (2011) have both been huge successes. He proved that Nollywood film is a mainstream and commercially viable option for Odeon.

It is a very quiet revolution for African film. Hoad writes in his article that 'Amata could be the savvy alumbus who encourages Nollywood to raise its game'. Could it not be the other way around? Sold out performances of Nollywood films challenging US blockbusters at the box office. The common criticism of Nollywood cinema is the lo-fi quality of the film material itself- it is often on video, with distorted audio and melodramatic acting. Stereotypes, sexism and violence are prevalent. Yet, narratives and quality are changing of their own accord, rather than from Hollywood's influence. The recent film The Figurine (2010) by Kunle Afolayan was a powerful and entertaining look at ritual belief, the role of women in contemporary Nigeria and the pressures of success. It is a convincing story about the meeting between metropolitan, contemporary people and the beliefs and rituals that still play a part in Nigerian society. It is a witty and thrilling imagining of how these two worlds meet, and interact.

Similarly, 'alt-Nollywood', pioneered by experimental filmmaker Zina Saro-Wiwa has been subverting many of the themes of Nollywood, creating acerbic and witty short films that challenge Nollywood on its own grounds. This is the way around we should be looking at Nollywood film, rather than judging its success on the level of assimilation certain Nollywood directors have found within the shallow glitter of Hollywood.

Things to watch:

Sweet Crude: a documentary by Sandy Cioffi, described by Steve Kretzmann, director of Oil Change International as "an incredible film that is moving, effective and is by far the most powerful educational and motivational tool that I've ever seen regarding the Delta."

On Nollywood and alt-Nollywood: This artist's talk with Zina Saro-Wiwa dicusses Nollywood and her films at Location One in NYC.

The African Cup of Nations Commercials

The semi-finals of the 2012 African Cup of Nations are played later today. I'll find a stream somewhere online (none of the American TV stations or sports channels are broadcasting the tournament live). As someone obsessed with media, I could not help but notice the TV commercials on Eurosport or any of the other channels whose streams of matches I've been lucky to get access to. Here's a sample of some of the commercials, including ones I have spotted online made specifically for the 2012 tournament.

Probably the most striking is Nike's "Next Generation" ad with Andre Ayew of Olympique Marseille and Ghana, Gervinho of Arsenal and Cote D'Ivoire, Adel Taarabt of Queens Park Rangers and Morocco and Kwadwo 'Kojo' Asamaoah of Udinese and Ghana. At least three of these players–Ayew, Gervinho and Asamaoah–will be involved in matches today. The ad is part of a series "The New Masters of Football" and aims to shake off "the stereotypical view of the African game." It opens with this voice over by an actor: "Too often we have seen African dreams turned to dust / Or end in defeat, no matter how glorious / We pledge to make a change / To break the cycle."

Then there's this ad shot in Dubai for Indian-owned phone company, Muse, in support of Cote d'Ivoire's national team. A few members of the Ivorian national team are joined by local actors.

Predictably there's an ad with children. Legendary Liberian footballer George Weah joins a group of children in Johannesburg's Soccer City to kick footballs into a goal stacked with drums. It's for another mobile and phone card company, Lebara.

Lebara also has another ad that looks like it was shot in South Africa. For this one they got the Indian composer A R Rahman to compose something:

Any ads I missed?

February 7, 2012

Cape Town's make-believe politics

Cape Town's local politics seems to be getting more and more distressing. Last week the Rondebosch Common, a public plot of open land in the leafy suburb of Rondebosch in Cape Town showed a bit more activity than usual. Cape Town's city council– run by the Democratic Alliance; South Africa's official opposition with 16 percent of the national vote–and the police cracked down on a proposed "people's jobs, housing and land summit" entitled Occupy Rondebosch Common. The city police acted in a show of force that even the centrist 'liberal' media called excessive, and others compared to Apartheid's suppression of dissent. The police even sprayed blue dye to disperse the peaceful protest. Around 40 people, mostly women, were arrested on site at the common and chief organizer Mario Wanza of the organization Proudly Manenberg was detained before he could even leave the Cape Flats. Mayor Patricia De Lille (a former trade unionist) was quick to call Wanza and his colleagues "agents of destruction."

The city claimed the protest was illegal, as the organisers didn't have permission to gather, allegedly because they turned up late for a meeting with the council.

What was interesting was that the Occupy group, which loosely consists of members of a number of organisations (including the Congress of South African Trade Unions and the small Institute for the Restoration of Aborigines of South Africa (check my post on Hangberg for a primer on postapartheid identity politics in Cape Town) are also using the logo and posters of the United Democratic Front (UDF), a crucial coalition of 400 different organisations that came together in opposition to the apartheid government during the 1980s but was disbanded after the ANC was unbanned. Some are criticizing this as a appropriation of the nostalgia bygone era, although judging by the way the city dealt with the issues, have we truly moved on since then? Cape Town remains one of the most racially and economically segregated cities in South Africa, and there aren't many signs of things getting better.

A friend of mine was amongst those who were arrested. She said that upon arrival at the police station she was verbally forced by police to sign a statement saying she committed "public violence", even though she was peaceful and did not resist arrest. The arrestees were detained until around midnight, all day unsure of whether they would have to sleep in the cells. They appeared in court on Monday, where all charges were dropped. Clearly the city was using heavy-handed scare tactics. This is not the first time, as seen recently in the violent clash over housing in Hangberg, Hout Bay, in early 2011 and which I documented in a documentary film.

All this plays out against ample favorable press for the DA, not only at home, but also abroad. Like this breezy article in The New York Times on Lindiwe Mazibuko, the DA's first black leader in parliament. The article never mentions what Mazibuko's actual politics and views are, besides the homily that government "empowers people to help themselves." Other than that we learn more about her hair. The writer also positions Mazibuko as the key to the DA shedding its "white" image, yet as far as I have experienced, Mazibuko is no drawing card to black middle class. Meanwhile it turns out that the DA youth wing's "interracial couple kissing" ad campaign was worse than Benetton politics. The ridicule was deserved. It turns out they bought the picture–part of a series by the same two models–for about $20 off a New York City-based stock photo site.

Music Break. Mufasa

Somali-Canadian R&B Singer A'maal Nuux wants to be Mufasa. The description of the song on Youtube says, "This song touches on the devastation and upheavals afflicting Somalia… offers a message of hope calling on the people that a devastated nation can actually rise from the ashes of war!" A little Somali pride in your radio R&B. I can't be mad. I appreciate that more and more artists aspiring to the mainstream in the Americas are able to foreground their African heritage. Not too long ago it would have been a detriment. And although not necessarily a direct reference to the Lion King, just like the American President she flips the stereotype. Nice one!

The Two Sudans

On July 6 2011, the world's diplomatic elite flocked to one of the globe's most underdeveloped regions to bask in the warm glow of the birth of a new nation. That South Sudan's struggle for independence had claimed the lives of an estimated 2million people, and that the majority of its inaugural citizens had been displaced by decades of war, ensured that the Juba inauguration was all the more remarkable – brimming with the promise of peace, and the fruits of freedom. Now, in an act of apparent economic suicide, South Sudan has literally turned off the taps of their economy. "This is a matter of respect," Pagan Amum, the South's chief negotiator with Khartoum asserted, "We may be poor, but we will be free." By shutting down 90% of the country's oil production Juba seems willing to entirely forego 98% of the government's non-aid related foreign currency earnings. How did we get here?

Recent events are almost inexplicable when one considers the developmental and economic progress that accrued to both Sudans in the six years that spanned the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) in 2005, and the independence of South Sudan last year.

But then again, perhaps not: Khartoum began to act in bad faith with regard to the terms of the CPA almost as soon as the ink had dried: siphoning money from the proceeds of oil fields in the South; failing to administer a referendum on the final status of the disputed, and oil rich, Abyei region; reneging on their commitment to conduct "popular consultation" processes in the border states of South Kordofan and Blue Nile; and failing to demobilize and integrate Northern rebel militias affiliated with the Sudanese People's Liberation Army (SPLM) into the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF).

As secession grew near, critical issues of resource division, citizenship, inherited debt, and the final status of borders remained unresolved. Hardliners, and military men, in the northern establishment, emasculated by the failure of Omar al-Bashir to extract any concessions to end or mitigate Sudan's pariah status, buttonholed the president in a soft coup, forestalling the prospect of effective conciliation with the South. Fratricidal, petty, and pathetic politicking is now the order of the day.

Rump Sudan now faces a chronic fiscal crisis. Having lost 75% of known oil reserves to the South, the Khartoum regime, under the shadow of the Arab Spring, must enact 26% spending reductions in the face of a restive population, whose marginal livelihoods are being squeezed at the crosshairs of inflation, failed or conflict affected cultivation, and the lifting of government subsidies on staples. The full extent of the bankruptcy of government's current fiscal positions was exposed in December when Finance Minister Ali Mahmood Abdel Rasool admitted to a hostile Majlis that current fuel subsidies accounted for a gobsmacking 25% of government expenditure.

That the SAF has invaded and occupied Abyei, and vast swathes of South Kordofan and Blue Nile states, will divert more resources to oppressive state apparatus in lieu of poverty reduction and the provision of basic services. The UN now estimates that as a consequence of these new conflicts a quarter of a million citizens have been "severely affected", and that half a million may require food aid. The government's refusal to allow international aid groups to work with conflict-affected populations has the potential to induce a catastrophic, but entirely avoidable, humanitarian disaster.

Moreover, the destabilization of Libya – actively supported by Bashir – has forced Darfuri rebels from their former safe haven. Notwithstanding the assassination of the leader of the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) in December, the influx of battle-hardened militia and military hardware to the Darfurs, and Kordofan states, has breathed new fire into that conflict. Increasing cooperation between the SPLM-North and Darfuri rebel groups now trace the contours of a new "South" and, potentially, protracted conflict.

Domestic protests – often spontaneous – have been suppressed, amid allegations of torture and human rights violations.

In this cauldron of unrest and economic decline, perhaps it is no surprise that the Sudanese government began to 'officially' confiscate Southern oil to offset their demands for a $36 a barrel surcharge to cover the costs of transit through the Red Sea pipeline. The South now accuses Khartoum of stealing more than $800m worth of oil, a charge that is not denied.

Ongoing efforts to negotiate a sustainable compromise appear to be floundering with the South offering to pay a $1 surcharge per barrel. Both sides are, moreover, insisting on linking any agreement to border disputes, allegations of proxy warfare, and the Abyei conflagration. The negotiating teams appear bent on holding hands and plunging off the economic precipice together.

The North may be in an economic crisis, but the South desperately needs money. Human development indicators for the region are abysmal, but for the South they are positively medieval. The influx of 362,000 'returnees' from the North, joined by throngs of refugees from Abyei and South Kordofan, has strained the limited welfare capacity of the new state, while bloody internecine violence in Warrap and Jonglei states continues to undermine internal security, with tens of thousands dead, and hundreds of thousands displaced. Khartoum will soon consider 700,000 South Sudanese resident in the North as foreign; their return would trigger unthinkable social destabilization.

Against this backdrop, the Government of South Sudan is shutting down oil production. If oil does not flow the pipeline will atrophy and become moribund, leaving both nations economically adrift in a sea of conflict.

With the United States utterly alienated from the process – comprehensive and longstanding sanctions against the North leaving them with few card to play – and both sides unwilling to consider the African Union's interventions, it is difficult to see who can bring the parties back from the cliff face.

China, however, could still play a significant and constructive role, but only if they were to blur the edges of a longstanding policy of non-interference in the sovereign affairs of African states. China's burgeoning and commodity intensive economy derives 6% of oil needs from Sudanese oil fields. There are also over 100 Chinese companies, with over 10,000 employees, heavily invested in the extraction and refinery capacity of both Sudans, whose security is increasingly tenuous. These sunk costs, in conjunction with the compounded opportunity cost of economic growth foregone as a consequence of diminished oil resources, could force China's hand. Already diplomats have been shuttling, amid calls for restraint. A selfish foreign policy could yet bring Sudan back from the brink.

How to feminise a tank

Nadine Hammam is an Egyptian artist making work around the embattled domain of gendered self-expression. We speak as she works on a series which will go to Art Dubai at the end of March. This, she tells me, addresses "political issues and gender issues, using the female nude". Gender is one of the Egypt revolution's most complex domains. Sophia Azeb has engaged with it in these pages. Sarah Topol has recently blogged in the IHT about sexual harassment Egyptian women have faced since the revolution. Hammam's work maps out the social and psychological position of the female body through the dialectic of the naked and the nude. A recent series, 'Heartless', featured the silhouettes of women, adorned with splatters of what might be blood, stamped with slogans like 'i need a revolver more than i need you'. I'm interested to know if her work consciously seeks out controversy, aiming to provoke political debate around gender. She insists it doesn't with a blankness that I believe:

I don't really care about what's acceptable and what's not. I've had a lot of no's in my career.

This new work, she says, is an attempt to form "iconographies of what's happening today." The situation in Egypt today is something Hammam has only recently been able to work through. She was asked to make a piece for Art Dubai last year, but refused:

I said I can't – I'm too emotional about it, I'm too involved. I need time to let it digest … I couldn't make work about it. I didn't know how I felt about it … I didn't know how to translate that into work.

She realized this during a recent interview:

We were talking about events in Fayoum, we were talking about the arms trade … I started talking about how I'd like to get my hands on something from that area. I started brainstorming … about the arms trade and arms from Libya … I wanted to get my hands on a tank … feminise a tank, something superviolent …

If the current situation in Egypt is an obstacle to the production of art, this is certainly a project which explores those difficulties:

If I could get funding to do it, I would do it … [but] when you get a lifesized tank, where do you put it? It would be a direct insult to the army.

Provoking the army is clearly not her priority. It's probably too easy as a female Egyptian artist. Hammam, like many Egyptians, felt overjoyed when the army entered Tahrir Square on the 29th January:

I even got on the tanks as they rolled in from the Rameses Hilton. Saturday, I got on a tank happy. … Oh my god the army are here to save us … There was a sense … the army was going to do what's right.

The last year has been a political maturity for generations of Egyptians, and the temptation to assume a position of cynicism must be tempting. The struggle continues, Hammam suggests, increasingly in the arena of media representation:

We are fighting a media war. What some of the television channels say … They say that in Tahrir there are only 2,000 people.

But, she suggests, art has a role beyond critique. The artist must not remain "reactive", stuck attacking regimes of meaning and representation, but must become "proactive":

It's like a husband and wife … I can keep calling you a liar … but until she gets up and says 'I've had enough, this is what I am going to about it' … Until we become proactive. I can't convince you that the army is a liar … until I show you a better way.

This impulse, to make romantic situations speak to political conflicts (and vice versa) is at the heart of Hammam's work. As surely as politics intervenes at the most personal levels, the personal is the most accessible domain in which political decisions are made. And most intimately known. Hammam's think about change, she says, applies in all areas of life:

Education, healthcare, social services. The whole thing. Across the board. For some reason, we can never agree. If we could take one village. If we were to implement that kind of social change. If there was one success story it would spread like wildfire. If there was one success story it would spread like wildfire. I don't think that calling you a liar will do anything to change that.

The pressure on Egyptian artists, to protest, to be exemplary, to make art which provides critique, and vision for the future is significant. The piece Hammam is working on at the moment is, she says, "proactive":

It's telling the army. It's direct – I don't know whether it's an attack or a commentary – without me saying anything. I'm using the icon of the tank. And the female figure. And I'm feminising the tank. I think it's a piece that has a lot to do with gender in Egypt. If you look at statistics alone – if you look at the lower classes. Mainly the women are the main workforce. Men stay at home. If these [were to] women mobilise …

Still, I wonder if the work Hammam makes would be shocking to some Egyptian women:

The liberals are very shocked by the work. I don't find it shocking. Other artists are far more shocking, far more erotic. The sister of a friend of mine is veiled, very conservative, very close to God. She had come over and I had said to her 'I don't know if your sister should come over'. [But] she came over and 'The Girl With The Hole In Her Heart' brought tears to her eyes. She brought another interpretation [to the work]: virginity. I was very surprised. This is not someone who was exposed to work.

The exposure of work remains something which she knows must be carefully controlled. Before the January protests, Hammam had posted some images of her work on Facebook. She soon took them off:

When you're in Tahrir you're judged because of what you wear and you're not veiled … I thought I can have dialogues with these people … I can break this barrier. But if they were then to see all this nudity they would judge me … If I were to bring my nudes to Tahrir, that would change. I would probably be labelled … the majority would not understand it … it would probably create a backlash, like Alia [Elmahdy]. It's not a productive.

I assume Hammam's thinking into the politics of the female body must have made Elmahdy's decision seem naïve, but she counters this:

I work with the nude. When I first heard someone had taken off their clothes. It sounded cool. When I first saw the photograph I was taken aback. It was a very stylised photo … the red ballerinas … the red clip in her hair … the position of her leg … slightly suggestive.

The decision to post the picture may have been naïve, but it was these stylistic decisions which made it such a problematic gesture.

I thought the picture was stunning, I loved the picture. I would have loved to see the picture in the setting of a gallery. [But] it did damage to the liberal cause.

And that is the difference between gestures like Elmahdy's media intervention and Hammam's work:

I'm not trying to shock people. What I make is really from my heart. The last series was a question: is it possible to love someone for ever, with that same passion or desire … If yes, okay, I haven't seen it. I lean towards the no …

But are there buyers for this work in Egypt? Yes, she says, but of "the collectors who do have female nudes, I can think of two who can put female nudes in their living room not their bedroom. There is nudity in Egypt. It does exist. They do buy it. But they will put it in the bedroom."

And has the revolution damaged this?

I think people were scared to invest in art. Were scared to go out. Investing in art is stage 5 of your daily life. People were scared to go out. Tahrir now is a parallel universe to the rest of Cairo. Certain people are going about their daily lives. And Tahrir is still going on. Whereas in the past people would stop their daily lives. Now you get people going to Tahrir then going out for drink in the evening.

This situation, in which riot becomes contained in the schedule of the mundane, is something Hammam's art militates against. The idea of democratic self-determination – which has recently authorised some notably undemocratic military interventions – must presume a definition of the self. This determining self, complete with a stable social identity and coherent desires, is one of democracy's most important fictions. Art which knows the fluidities of the self, and confronts the attempt by an apparatus of power to coerce them into containment is especially important in this moment of national reformation. These nudes are the brutal and exterior selves formed by the shocks of political life. This exteriority is punctured by an intimate presence which is both a wound and a sign of life. Those who are fighting for political self-determination are no more than a mass of people each longing for love. This work recognises an interiority which must survive at any cost.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers