Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 563

February 15, 2012

Rwandan film part of prestigious traveling film exhibition

In December, the Global Film Initiative announced ten award winning narrative feature films to represent their Global Lens 2012 series, a collaboration between MoMA and the Global Film Initiative, which will tour the world as a traveling film exhibition. The series aims to coax filmmakers in emerging film communities into action by showcasing the talents of contemporary global filmmakers. The films selected for this years collection come from Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Iran, Iraq, Morocco, Rwanda and Turkey — a truly exciting cross section of recent world cinema output. Rwandan director Kivu Ruhorahoza's Matière Grise (Grey Matter) was one of the films selected, following a fantastic reception at various film festivals. The first film made by a Rwandan, living in Rwanda, and shot in Kigali, Ruhorahoza's film premiered at Tribeca in 2011, and portrays life in Rwanda today, merging fantasy and reality through the confused lens of memory and trauma to depict the aftermath of the genocide.

The jury at Tribeca gave Grey Matter special mention… 'for it audacious and experimental approach, the film speaks of recent horros and genocide with great originality'.

The Shadow and Act blog, that champions film by people of African descent (and now part of Indiewire) called Grey Matter 'Fellini-esque', linking the anguished filmmaker-within storyline to Fellini's own 8 1/2 , 'as film's that centre on filmmakers in some turmoil, as the dream world blurs with reality…'

Christopher Bell on The Playlist blog (also at Indiewire) has reservations about the film, suggesting that it falls short of the mesmerizing and hypnotic qualities of the films it is so clearly influenced by — Miguel Gomes' Our Beloved Month of August or much of Apichatpong Weerasethakul's work. Yet it does, he writes, successfully build a powerful force of a "deep, pent-up rage bubbling throughout the film, one that never quite explodes but is still thoroughly felt."

In The New York Times, critic David DeWitt observes that 'there are no emotional fireworks here, just smoldering, quiet, lonely agony.'

You can read an interview with Kivu in The New York Times here.

January in Cairo IV: the two faces of Egyptian art

Om Kalthoum, the late great Egyptian singer, stands in Khaled Hafez studio. Her eyes are closed, her mouth open in song or lament. There is not one of her, but six (including a shadow), laser-printed repetitively across a wide canvas. She has her trademark hair, evening dress, large earrings. One hand raised in emphasis. The other holds a curious flesh-coloured object. A stained shawl? A chicken with its neck wrung? 'First as tragedy, then as farce.' Khaled, one of the most internationally-celebrated Egyptian painters, is working through the visual clichés of her legacy. One of Kalthoum's nicknames is Arabic for "the woman", a word he says comes from Isis. For Khaled, the tension between her quest for a secular womanhood, and the old-fashioned elegance she represents, makes her an embodiment of independent Egypt. I visited Khaled's studio in Heliopolis at the beginning of January to ask for his perspective on contemporary art and the situation in Cairo.

"I was teaching in January [2011] and, for the first time, no students turned up. I said 'Okay, we will arrange for another day.' But the next week they said 'are you coming to the protest?'"

Khaled went to school with Gamal Mubarak ("we played soccer together"). This is perhaps partly why the revolution represented such a shock: "we were politically programmed. We were deceived." Khaled trained as a doctor, and during the protests he revisited this profession; he and his wife visited Tahrir Square on alternate days, taking turns to look after the children.

Khaled has, like many others, found it hard to make work in the last year:

"After the revolution, I did not think I would go back to painting … I started work on a Tahrir Square painting then stopped. I founded it physically difficult … The work was too literal, too sensational. When I look at it I admire only the effort."

But eventually the work has recommenced: he made video diaries, three simultaneous videos of found footage. And he started painting again: "painting is like singing, dancing, squash, you must do it every day. Two months ago I started dripping and underpainting. It is the best thing in the world to do when you are not inspired."

His studio is now lined with canvases, dripping with colour, destined for exhibition at the Safarkhan gallery. These are evidence of furious recent activity: 20 square metres painted in 29 days. Khaled tells me he wants to turn the gallery into a 'tomb', to make the viewer 'suffocate'.

His work before the uprisings was beginning to develop a visual iconography whose grammar originates in ancient Egyptian painting. The tombs at Saqqara, or that of Rameses III, he says, evidence the creation of 'rules for painting: flat, floor-to-ceiling, organised from right-to-left and left-to-right'. These paintings have a 'rigorous layout' like that of modern advertising. Inspired by the collections of imagery and prayers in the 'Book of the Dead', this series is called 'The Book of Flight'. Many Egyptian artists have decided to leave since the uprisings. Flight must be a temptation and a dilemma for the artist. To confront the situation or escape from it.

The vocabulary of Khaled's work is however, explicitly modern. Watching a child play with military toys, he realised the child knew all the correct names for the technologies, and decided he wanted to build a 'new hieroglyphics out of military symbols … a new alphabet.' This work was started in isolation during a residency at the McColl Center in North Carolina. Configurations of soldiers fill the canvases, tiny bodies arranged into what look, at a distance, like pure patterns.

Khaled claims that in his paintings there are 'no emotional gestures'. Modernist Western painting is a strong influence: Rauschenberg, Picasso, Klimt. Basquiat is "like a God". I wonder if there is some antipathy in contemporary art towards painting. There are young artists in Egypt who "get together and say 'Alain Badiou says painting is dead.' Fuck Alain Badiou."

With the evocation of ancient iconography, I wonder, does this work represent the search for a pre-Islamic state? Do these visual archaeologies involve attempts to validate the artist's work?

He shows me a new painting, "my Sister Julia painting": Julia Robert's face emerges from a burka. This is a response, he says, to Salafi demonstrations against the reports that two Coptic sisters had been prevented from converting to Islam.

Khaled also experiments in film, and his 2006 video piece 'Revolution', has been described as premonitory. "But," he says, "it referred to previous revolutions of the 1950s and its promises …" Promises whose non-fulfilment led to last year's uprisings. The screen is split into three, representing the splitting between the promises of revolution, its real motivations, and inevitable outcome. "I am always in search of déjà vu," he reflects.

This attitude manifests itself in the dialogue between the ancient and the modern which dominates his painting. Khaled is a student of iconography, passionately interested in the visual archaeology of symbols. The star of David, he tells me, reaching over to point at an image of a six-pointed star, is also found in ancient Egypt. This 'cultural recycling' is also present in the Bible: Abraham, Sara, Adam, all have their etymological origin in Egyptian mythology. Batman, he gestures towards a crouching, long-eared creature, comes from the Egyptian god Amun-Ra.

Are Egyptians, then, the best pop artists?

"Egypt invented beer, wine … the modern army," he quickly responds, "does that mean ours is the best?"

With some distance from last year's uprising, if the violence of Egypt's political transition does not pose greater problems, Khaled's work will no doubt develop a sophisticated system for deciphering the present. He has four paintings in "Hajj" at the British Museum and exhibitions coming up in Manchester, Kaohsiung, and Havana.

Art in Egypt must be janus-faced. It contends with the past – not merely with last year's spectacular events, or the fifty years of independence but with the whole visual history of this civilisation – and looks towards a future populated with uncertainties. The establishment of a new government and writing of a new constitution may cause new tensions leading to years of conflict. Art has been challenged to justify itself as Egyptian, and popular elements of society are seeking its total alienation from national discourses; but Egyptian contemporary art is playing a more important part than ever before in the international conversation art is. And Khaled would surely want to remind us that Janus too was invented in Egypt.

February 14, 2012

Music Break. Sababu

Belgian band Zita Swoon, world-famous in their own country –I'm biased– recorded an easy listening album with the help of Burkinabé artists Awa Demé and Mamadou Diabaté Kibié. It sounds and looks exactly as I expected it to.

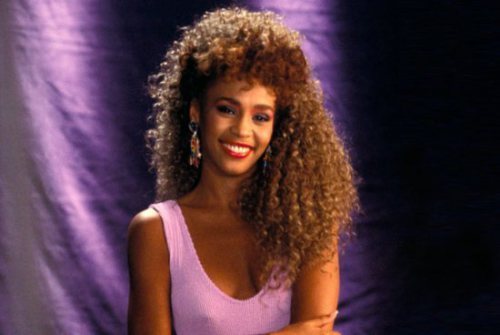

The Whitney Soundtrack

Written by Keguro Macharia

I grew up listening to Whitney Houston. Not simply in the sense that she was famous as I entered adolescence, but that the affect-world she created saturated and colored my sense of what it meant to live in the world. Michael Jackson's "Thriller" was fun, Prince was nice to like, New Edition appealing, but Whitney's "Greatest Love of All" felt transformative. Along with my best friend then—I claimed him as a best friend while he tolerated me—I memorized and sang the song, performing it, if memory serves, for a school assembly. I might be misremembering this. I do remember how affirming it was to believe, as a child, that children were "the future," and how, as I entered my non-rebellious adolescence as a very religious person, I embraced the possibilities of living "as I believed," determined not to "walk in anyone's shadow."

I want to register the importance of these sentiments. Today, I might sneer at everything that young Keguro did not know. But, as I note in recent writing, "I am learning to treasure the ecstasies of my youth." Not nostalgia, but a deep respect for the intuition of youth—a moment when, to use Whitney, I was "living on feelings".

Amid what feels like a flood of sneers about Whitney's "banal" songs—great voice, but terrible lyrics and style, I've read—I keep thinking about what it means to lose the soundtrack to one's life. About the worlds of loss and desire Whitney enabled: she was my gateway to Billie Holiday and Bessie Smith and Abbey Lincoln, all very different vocalists. The foundation she laid let me spend a heartbroken two weeks in Seattle playing Bessie over and over and over.

But I'm trying to get to something else.

As I watch and re-watch her videos, even those I have not seen for a long time, I'm reminded that I *know* Whitney's voice—the runs, the catches, the slight shifts, the trembles, the hand gestures, the shoulder movements, the eye rolls. I *know* Whitney. She stamped my life in ways I will probably never be able to recognize.

What does it mean to lose the soundtrack to one's life?

I've tried collecting music before, but I am terrible at it. I yearn for the familiar. I am mostly indifferent to the new. And despite efforts from good friends to diversify my tastes, I incline toward particular sounds, particular singers, particular styles. Whitney is my one constant. In my years of collecting and purging music collections, I have always collected her. I don't have a Whitney habit—I don't listen to her all the time—but I like knowing she's around. I like to glide on her voice.

It is, after all, the voice that ushered me into adulthood. In the late 90s, I spent more time dancing to Whitney dance mixes than to anything else. She was my "welcome to America" figure: I didn't know much about rock, had to discover about Janis Joplin, but Whitney was familiar. I lack the language to describe the effect of her voice, the "vibrations" of her presence—the wide, wide smile; the playful grin; the candy colors of her first videos. She was fun. And, what some call "over-processed" and "commercial"—can I pause to say how much I dislike music critics who sneer at "popular" taste—I found enabling.

I keep coming back to the word "enabling," perhaps because I have been thinking about love in Fanon, thinking, that is, about racial life that is not a Greek tragedy. Perhaps this is why I so resent the idea that many British shows champion: Othello is the best role for black men. See Idris Elba in Luther. At times, many times, I have craved the quotidian.

Over the past ten years, the "quotidian" has been one of my critical foundations—I don't have a theory of it and I don't know that I need one. I think about what might be termed the "black ordinary" when I'm in the States and about the "Kenyan ordinary," when I'm in Nairobi. I want to register not simplicity, that's not what it is, but the thickness of daily living, of encounter and solitude, stasis and movement, flavor and sensation. Whitney has been part of my quotidian—my experience with feeling and being—for as long as I had taste that was not borrowed or simply available. (Some might question "taste," especially those who remember my daisy dukes or, earlier, my maroon moccasins, as we termed them.)

I chose Whitney.

As I watch and re-watch her, I remember the little queer boy who sang soprano for far too long and found refuge in Whitney's vibrations. My vocal chords remember patterns, move silently, aching to chase notes I lost a long time ago.

Her not being in the world makes those notes more elusive.

* Keguro Macharia blogs at Gukira. He generously allowed us this cross-post.

Nigeria Fashion Week

Probably to coincide with New York Fashion Week, Vice released the Nigerian installment of its "Fashion International" series. It's not bad considering how Vice usually treats Africa (reference: Congo, Liberia and Ghana) and it definitely captures some of the energy of Nigeria. But it can't help itself. We're barely a minute into Vice's report ("looking for something beautiful behind the depressing headlines") on Nigeria's 2011 fashion week when we're told Lagos is troubled by "civil unrest, religious tension and wide-spread corruption" that "have lead to calls for the resignation of long-standing president Goodluck Jonathan." Pretty prescient. The first Nigerian to get some words in is the "fantastically named" fashion week's organizer Lexy Mojo-Eyes "who looks like Don King"; next up are the fashion week's female models (but it quickly gets too "naked", so the reporter moves on to the male models), wondering why they love "to represent Africa."

It gets better after the 5:00 mark, pitting general male vanity against the recently proposed self-righteous anti-gay bill and homophobic sentiments in local press. (We'll ignore how the reporter slides from 'traditional African beauty' over 'pure Nigerian beauty' to back-stage 'pure Nigerian chaos' — do French fashion back-stages look anything less chaotic?)

It's a decent document (and rare in its portraying of gay figures –albeit in a stereotypical fashion context– where Nigerian pastors and politicians would rather see them outlawed).

One question though: what is it about "being on a yacht under African skies" that makes journalists "lose control of [their] senses"?

February 13, 2012

Chipolopolo Music

The closer we got to Sunday's Africa Cup of Nations final, the more Zambian music videos started appearing in our feedreaders (especially: Zed Beats). Mag44, Tio, Pompi & Chungu take the prize for the best tune, Tribal Cousins for the best moves:

Chipolopolo on Music

The closer we came to Sunday's Africa Cup of Nations final, the more Zambian music videos started appearing in our feedreaders (especially: Zed Beats). Mag44, Tio, Pompi & Chungu take the prize for the best tune, Tribal Cousins for the best moves:

Financial Times blues

[image error]

I read The Financial Times because they cover the news that is essential to capital and those who rule us. For example, last week, while the occasional story about South Africa online is either about Die Antwoord's performance on David Letterman (awkward), Julius Malema's disciplinary hearing (I thought we were done with him) or who was wearing what at President Jacob Zuma's State of the Nation address (what did he say?), the FT focuses on what really matters: What is the South African ruling party thinking about doing to the mining industry. They've had at least 2 stories last week from their Johannesburg correspondent Andrew England on the subject and an editorial on Friday. Though the stories and editorial are full of deliberate biases and timely leaks, the long and short of it is that, despite Malema's rhetoric, the ANC is ruling out nationalization and instead is thinking about "ways in which mining profits can be redistributed more fairly." This includes "a resource rent tax of 50 per cent." (The FT approves of course.) That said, there's something I don't get about the FT: its op-ed or "Comment" page.

Take last week. First they had Mohamed el Baradai, the liberal Egyptian scientist who was hoping to run for president post-Mubarak, but has now withdrawn to a role in civil society. (He wants to train young liberals to run in future elections.) His column was timely as it coincided with the one year anniversary of the fall of Mubarak on February 11. El Baradai soberly reviewed recent events and then added this:

Some are sceptical about the influence of the Islamists. After decades of banishment from the political scene, they have no experience in governing. Before the revolution, we fought together; in the new Egypt, we have differing perspectives. On the eve of January 28 last year, two of their leaders were arrested leaving my home. One is now the speaker of the parliament. I called him last week to wish him success. I predict the Islamists will embrace other political factions, support free markets and be pragmatic.

So, you may disagree with his politics, but he lives in Egypt and knows the ground and is politically astute.

Then Thursday, the page ran an op-ed by Ayaan Hirsi Ali, the American-based Somali writer (her husband is Niall Ferguson) to present what amounted to a counterargument. If you expected some nuance from her, what she predictably presented was her usual collection of Islamic stereotypes. (We're not surprised of course.)

If that was not enough, in between, they had Dambisa Moyo–who gave us the badly argued "Dead Aid" book–write that what Africa needs right now is more free market capitalism.

Rick Ross is the boss

For some odd reason the latest issue of The New Yorker ran a profile of rapper Rick Ross. Lots of good, clever writing by Sasha Frere Jones on familiar controversies about Ross (for example, Frere Jones calls Ross out for lying about his real life drug dealer exploits; show me the rapper who doesn't make things up) and gratuitous breakdown of Ross' mostly misogynistic lyrics. The oddest part was where the magazine encourages its readers to go and listen to Ross's music on the New Yorker website. (Just imagine the reader.) Anyway, it reminded me of the two-part "vlog" (video blog) that Ross's people produced of his late 2011 trips to South Africa and Gabon. That's part one above. It's a full 9 minutes of product placement, driving cars, scenes from a casino, screaming fans and Ross occasionally reminding people of his surroundings ("Johannesburg … one of the most beautiful places I've ever been"). Here's part 2, still "South Africa Vlog Part 2″ but which is really about his trip to Gabon and him talking about the chicken pasta Kenya Airways served it ("that was love") and how he thought Kilamanjaro was the name for weed.

Introducing: Angolan singer Aline Frazão

Angolan music has its share of famed female voices. Belita Palma, Lourdes Van Dunem, and Dina Santos from the golden years of semba in the 1960s and 1970s, Nany and Clara Monteiro from the 1980s, as Gingas do Maculusso from the 1990s, and in the 2000s Yola Araujo, Yola Semedo and Perola, among a long list of other contenders. The most recent debut, Aline Frazão, draws deeply from the earliest generation and from a wealth of other sources, trans and circum-Atlantic. Unlike her predecessors, she was born in Luanda but currently resides in Santiago de Compostela, in Galícia, Spain.

Her first CD, Clave Bantu, is an independent production of eleven songs, all but two written by Ms. Frazão. The other two, Amanheceu (Dawn) and O Ceu da Tua Boca (The Roof of Your Mouth) were written by the highly regarded Angolan writers Ondjaki and José Eduardo Agualusa, respectively. With Frazão on guitar and vocals, Carlos Freire (Galícia) on percussion and Jose Manuel Díaz (Cuba) on bass, Clave Bantu evokes and returns to patterns that structure the rhythms of African musics and those of the African diaspora.

This video is for the first song on the album Assinatura de Sal (Salt's Signature). Shot in black and white, it nicely underscores the clarity of the arrangement and the brightness of Frazão's voice and the percussion:

In January Ms. Frazão was interviewed on a Portuguese television program called "Ethnicities." Her unflappable poise in the face of the interviewer's flattery and leading questions says much more about her decision to move from Portugal to Spain than her direct answer to the interviewer's query about re-locating to Portugal. As the album cover shows, with birds so easily alit on her tresses, why would she settle in Lisbon or thereabouts and subject herself to the pigeon-holing practices of post-colonial Portuguese paternalism?

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers