Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 568

February 2, 2012

Laduma

During the summer I was interviewed for a new film about how a group of American fans experienced the 2010 World Cup in South Africa, including the qualifying leading up to it. I think I made the cut. The trailer for the film, "Laduma" is now on Youtube and it is hitting the festival circuit (it's showing tomorrow night in Philadelphia, at a film festival in Pennsylvania next month and I know there's a New York City screening also lined up in the near future). You can see my man Tony Karon, who co-teaches a regular 'Global Soccer, Global Politics' course (Fall 2011 syllabus here) with me at The New School, in the trailer above. Other talking heads interviewed in the film include ESPN's Bob Ley and Sports Illustrated's soccer writer Grant Wahl. Here's the Facebook page for updates.

Salone Got Riddim

AIAC contributor Anni Lyngskaer just posted this short video showcasing the rhythm of daily life in Sierra Leone, and the dancing talents of the country's women. It's a really nicely shot and edited clip, plus the incorporation of sounds corresponding to the action makes for an interesting audio visual experience. Great job Anni!

February 1, 2012

Ahdaf Soueif's Cairo

Days after "The Economist" decided no-one in the "Middle East" reads books (I'm serious, read the piece here), Ahdaf Soueif dedicated a short piece to Cairo in Newsweek. Just like Youssef Chahine's Cairo, beautifully expressed on film, Soueif identifies the ugliness that exists alongside the lovely in al Qahira. If the following is a taste of what the novelist's new book, Cairo: My City, Our Revolution, will express, I am eager to continue reading.

Small art galleries opened, and tiny performance spaces, and new bands formed across the musical spectrum. Mosques and cultural centers clutched at the derelict spaces under flyovers. Green spaces vanished, but every night the bridges would be crammed with Cairenes taking the air. We suffered a massive shortage of affordable housing, but every night you'd see a bride starring in her wedding procession in the street. Unemployment ran at 20 percent, and every evening there was singing and drumming from the cheap, bright, noisy little pleasure boats crisscrossing the river.

Trees that were not cut down refused to die. They got dustier, some of their branches grew bare, but they grew. We looked out anxiously for the giant baobab in Sheikh Marsafy Street in Zamalek, for the Indian figs on the Garden City Corniche, for what my kids called the Jurassic Park trees by the zoo. If they cut a tree down, it grew shoots. If they hammered an iron fence into its roots, the tree would lean into the iron, lean on it. If a building crowded the side of a tree, the tree grew its other side bigger, lopsided. I knew trees that couldn't manage leaves anymore but put all they had into a once-a-year burst of pink flowers. And once I saw a tree that seemed looked after, that had just been washed: it couldn't stop dancing.

Photo Credit: Hossam el-Hamalawy

The Toto 'Africa' Meme N°2. Madlib and GZA

Remember when we promised we'd start a weekly Toto "Africa" meme. On Wednesdays. Here's the second installment: Track no.2 off Madlib's Medicine Show #13: Black Tapes. It features GZA of the Wu Tang Clan. Makes even Toto sound better.

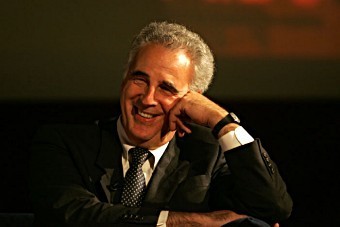

Trouble at the Global Fund

As Brett pointed out at the end of 2011, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB & Malaria (GFATM) recently had to cancel a new round of grants because funding has severely declined, and commitments made by donor countries have yet to materialize. As a result of the lack of funding, progress in many countries against the three diseases will be crippled until GFATM has the resources it needs. According to Medecins Sans Frontieres, 500 people marched in Nairobi on January 30th to protest the lack of funding for GFATM, which will directly impact people in Kenya. The Executive Director of the Global Fund, Michel Kazatchkine (in the picture above), also resigned last week.

In his resignation letter, Kazatchkine wrote,

Today, the Global Fund stands at a cross-road. In the international political economy, power-balances are shifting and new alignments of countries and decision-making institutions are emerging or will have to be developed to achieve global goals. Within the area of global health, the emergency approaches of the past decade are giving way to concerns about how to ensure long-term sustainability, while at the same time, efficiency is becoming a dominant measure of success.

"It is almost possible to hear Kazatchkine spitting out the words 'sustainability' and 'efficiency'," wrote long-time HIV journalist Laurie Garret in a recent analysis of GFATM's current situation in Nature, titled, "Global health hits crisis point."

In response to some of the recent news coverage of GFATM, the clever Auntie Retroviral has created a video to educate viewers on 'Global Fund Villains' – the people and issues which the Global Fund has dealt with in trying to ensure people around the world have access to life-saving medicine.

Die Antwoord butchering old beats

Going through photographer Roger Ballen's Boarding House series, each portrait made me wonder: "but what are these people in the photographs doing after the shoot?" Ballen's portraits are detailed, staged pictures of unnamed human figures, often with out-of-place props (rats, crosses, dolls…) in the same frame, always against a dead cold grey background. I failed to imagine them to be alive, real, or moving. Watching the music video that Ballen directed for South African crew Die Antwoord ("from da dark dangerous depths of Afrika" — their words) changed that a little. The figures do come to life. But I never imagined them dancing to an old beat.

I didn't imagine them freaking out to hardcore bass drum gabber beats, that Dutch sound which flooded the clubs in the nineties — those records now safely stored somewhere in my basement. I imagined the figures as puppets in an American-South African photographer's play, hinting at what he believes is an undiscovered surreal mental wasteland, that of poor whites, poor white South Africans, poor Afrikaners. It's the same trope Die Antwoord played with, and it's a trope we won't write about again.

Although some people are still tempted to consider them as being exemplary of white South Africans' (and Afrikaners in particular) "liberation" through art after Apartheid (as this article in the New York Times suggests), I don't believe Die Antwoord's essence lies in their projected identity, nor is the latter a useful concept to explain their runaway success.

I don't think they ever wanted to be regarded as 'Afrikaans artists'; they are only Afrikaans in so far as the press, blogs and online trolls believe them to be Afrikaans or poor Afrikaners. The new album, tellingly, hardly has any Afrikaans lyrics on it — unless you don't count the odious lines "Ek's 'n lanie, jy's 'n gam/want jy lam in die mang/met jou slang in 'n man" on 'I Fink You Freeky' [translated: "I am a white boss, you're a child of Ham/'cause you're locked up in jail/with your snake [penis] inside a man"].

Sure, there's some swearing and a skit in Afrikaans, but when Ninja for example raps how they broke with the American record deal that got South African press hyped up, he does so in English.

What they always did want though, is to play with the spectacular to get people's attention. As one does as an artist, I assume.

Die Antwoord play the game well; whether they play it fair is open for interpretation.

What they still do badly is "borrowing" from other people's work. Ripping Jane Alexander's sculpture Butcher Boys in the album trailer — without the South African artist's knowing — is one example, while 'I Fink You Freeky' not just seems to take the title and the sound of LFO's track 'Freak' but also an idea from this video made for that same LFO track. And maybe for good reason. If your songs don't differ much from what kids growing up in the nineties listened and danced to, you better come up with striking visuals and clever marketing.

And this is how Diane Coetzer, in an "interview" for the South African version of Rolling Stone (which put them on the cover), deals with questions of appropriation and race. She has it in for "South African critics who accuse the group of cultural appropriation (or worse) and spend hours analysing why two white South Africans shouldn't be stepping over the border into [coloured] Mitchell's Plain or Fietas to mine the lives of those who reside there." We learn that Die Antwoord's "ruthless loyalty to their imagination are the sole boundaries." Yes.

Anyway, good PR helps. And it helps to be well connected. (Diane Coetzer's partner is Die Antwoord's music publisher.) The PR worked last time, and so it will this time. The New York Times fell for it (including misrepresenting their critics) and fashion designer Alexander Wang flies them in for his new spring campaign.

By the way, I see Welsh rock band Feeder's using a Ballen portrait for their cover art too. It's becoming a trend. And it sells.

'Very African and Very Modern'

Written by Wayne Marshall*

As if there weren't already enough to tease out about Konono N°1 and Congotronics, a recent article in The Guardian points to a song and video called "Karibu Ya Bintou" by Baloji, a Congo-born rapper who cut his teeth on the Belgian hip-hop scene but who has worked over the last few years to return to "roots" — in part by incorporating "traditional" sounds of the Congo, from soukous guitars to Konono's hallmark distorted likembé. The latter can be heard supporting the vivid video for "Karibu Ya Bintou":

It may be tempting to read something like "Karibu Ya Bintou" as a relatively straightforward exercise in "indigenizing" or localizing hip-hop, but the story of Baloji's transnational musical moorings — especially his ambivalence toward Congolese pop — complicates such an interpretation:

His first rap outfit, Les Malfrats Linguistiques ("The Linguistic Hustlers"), morphed into Starflam and Baloji became something of a Belgian hip-hop heartthrob. Meanwhile, living above a legendary record store, Caroline Music, in Liège did wonders for his musical education. "I heard everything…PiL, Kraftwerk, Queens of the Stone Age, the Smiths…"

Despite suffering from the rampant racism of smalltown Belgium – he was almost deported back to the Congo at the age of 20 – Baloji can thank his adoptive country for the eclecticism of his style. Until recently, however, he hated most African music, especially Congolese soukous, the bedrock style of post-independence pan-African pop. "For me, it was the worst music in the world," he says. Nonetheless, when he received a letter from his mother out of the blue, in 2007, his Congolese heritage came back into his life with a vengeance. It inspired Baloji to return to his roots and record an album – a kind of soundtrack without a film – to tell his mother what his life had been like over the past 20 years.

That said, it's perhaps telling — as with the success of Crammed Discs' marketing of Konono N°1 as Congotronics — that Baloji would find the greatest interest in his work at precisely the moment he decides to place himself on a map that is easy enough to read.

Legibility does have its advantages. So it's not terribly surprising that Baloji's surrender to soukous on another song, "Independence," ends up serving as a vehicle for a sort of Congolese nationalism, if one that strongly resists the authority of the state. As with "Karibu Ya Bintou," the video is directed by the duo Spike & Jones, who have an awesome name and seem to make pretty awesome clips:

Most poignant though, I think, are Baloji's own words on the matter of musical heritage and nationhood, or of signifying Africanness vis-a-vis certain source material. Here he shows himself to be, among other things, a thoughtful student of hip-hop, which, for all the dots it connects around the world, clearly draws plenty of lines in the process

I want to make music that is very African and very modern. You have to be proud of who you are. You can sample Bob James or Curtis Mayfield, but it means more when Talib Kweli or Kanye West sample them because that's their heritage. But we Africans also have an interesting heritage, which has richness and a diversity that is huge and under-exploited. We can also go deep into it and make it modern, celebrate its value, just like the Americans.

Putting aside the gnarly notion that Bob James constitutes some part of Kweli's and Kanye's heritage (which he surely does, at least in Nautilus and Mardi Gras), I can't help but hear echoes of Baaba Maal's "Yela" (as discussed in this space almost 3 years ago to the day), which Maal himself refers to as "ancient African music" despite also noting that it sounds a lot "like reggae" — not to mention, of course (as also shared 3 years back), Christopher Waterman's classic article about jùjú, "Our Tradition Is a Very Modern Tradition": Pan-Yoruba Music and the Construction of Pan-Yoruba Identity.

In case you missed that one way back when.

If I may be allowed one last little addendum, I'd like to share a recording that seems somewhat germane. While revisiting The Noise 6 for the post I wrote for LargeUp, I came across a real gem of a pre-reggaeton track. Don't get me wrong, the Ivy Queen and Bebe songs are standouts, to be sure, but the final track — #16 to be exact — is definitely the biggest eyebrow-raiser. It's worth noting, if you don't know, that the last tracks on proto-reggaeton albums are often the weirdest, and this one, simply labeled "Bonus Track"

As you'll hear, there's definitely a nod to "Whoomp! (There It Is)" and no doubt a few other jams from the Miami-Atlanta axis (though all the percussion can make it sound a bit like drum'n'bass at times, save for the tempo). Oh, yeah, and there's the appearance of that ol' "Egyptian" melody.

Although plenty is going over my head, no doubt, I suspect this is about as allusive as any other track from this era, which means it's utterly full of vocal references and direct samples. It definitely gives a good sense of how widely Puerto Ricans were listening to hip-hop and contemporary club music as they sought to synthesize their own thing. No doubt for plenty of listeners — and maybe the producers and performers themselves — such a track might even sound both "very African and very modern."

* This post first appeared on Wayne's blog Wayne and Wax. He has kindly agreed to us republishing it here.

Very African and Very Modern

Written by Wayne Marshall*

As if there weren't already enough to tease out about Konono N°1 and Congotronics, a recent article in The Guardian points to a song and video called "Karibu Ya Bintou" by Baloji, a Congo-born rapper who cut his teeth on the Belgian hip-hop scene but who has worked over the last few years to return to "roots" — in part by incorporating "traditional" sounds of the Congo, from soukous guitars to Konono's hallmark distorted likembé. The latter can be heard supporting the vivid video for "Karibu Ya Bintou":

It may be tempting to read something like "Karibu Ya Bintou" as a relatively straightforward exercise in "indigenizing" or localizing hip-hop, but the story of Baloji's transnational musical moorings — especially his ambivalence toward Congolese pop — complicates such an interpretation:

His first rap outfit, Les Malfrats Linguistiques ("The Linguistic Hustlers"), morphed into Starflam and Baloji became something of a Belgian hip-hop heartthrob. Meanwhile, living above a legendary record store, Caroline Music, in Liège did wonders for his musical education. "I heard everything…PiL, Kraftwerk, Queens of the Stone Age, the Smiths…"

Despite suffering from the rampant racism of smalltown Belgium – he was almost deported back to the Congo at the age of 20 – Baloji can thank his adoptive country for the eclecticism of his style. Until recently, however, he hated most African music, especially Congolese soukous, the bedrock style of post-independence pan-African pop. "For me, it was the worst music in the world," he says. Nonetheless, when he received a letter from his mother out of the blue, in 2007, his Congolese heritage came back into his life with a vengeance. It inspired Baloji to return to his roots and record an album – a kind of soundtrack without a film – to tell his mother what his life had been like over the past 20 years.

That said, it's perhaps telling — as with the success of Crammed Discs' marketing of Konono N°1 as Congotronics — that Baloji would find the greatest interest in his work at precisely the moment he decides to place himself on a map that is easy enough to read.

Legibility does have its advantages. So it's not terribly surprising that Baloji's surrender to soukous on another song, "Independence," ends up serving as a vehicle for a sort of Congolese nationalism, if one that strongly resists the authority of the state. As with "Karibu Ya Bintou," the video is directed by the duo Spike & Jones, who have an awesome name and seem to make pretty awesome clips:

Most poignant though, I think, are Baloji's own words on the matter of musical heritage and nationhood, or of signifying Africanness vis-a-vis certain source material. Here he shows himself to be, among other things, a thoughtful student of hip-hop, which, for all the dots it connects around the world, clearly draws plenty of lines in the process

I want to make music that is very African and very modern. You have to be proud of who you are. You can sample Bob James or Curtis Mayfield, but it means more when Talib Kweli or Kanye West sample them because that's their heritage. But we Africans also have an interesting heritage, which has richness and a diversity that is huge and under-exploited. We can also go deep into it and make it modern, celebrate its value, just like the Americans.

Putting aside the gnarly notion that Bob James constitutes some part of Kweli's and Kanye's heritage (which he surely does, at least in Nautilus and Mardi Gras), I can't help but hear echoes of Baaba Maal's "Yela" (as discussed in this space almost 3 years ago to the day), which Maal himself refers to as "ancient African music" despite also noting that it sounds a lot "like reggae" — not to mention, of course (as also shared 3 years back), Christopher Waterman's classic article about jùjú, "Our Tradition Is a Very Modern Tradition": Pan-Yoruba Music and the Construction of Pan-Yoruba Identity.

In case you missed that one way back when.

If I may be allowed one last little addendum, I'd like to share a recording that seems somewhat germane. While revisiting The Noise 6 for the post I wrote for LargeUp, I came across a real gem of a pre-reggaeton track. Don't get me wrong, the Ivy Queen and Bebe songs are standouts, to be sure, but the final track — #16 to be exact — is definitely the biggest eyebrow-raiser. It's worth noting, if you don't know, that the last tracks on proto-reggaeton albums are often the weirdest, and this one, simply labeled "Bonus Track"

As you'll hear, there's definitely a nod to "Whoomp! (There It Is)" and no doubt a few other jams from the Miami-Atlanta axis (though all the percussion can make it sound a bit like drum'n'bass at times, save for the tempo). Oh, yeah, and there's the appearance of that ol' "Egyptian" melody.

Although plenty is going over my head, no doubt, I suspect this is about as allusive as any other track from this era, which means it's utterly full of vocal references and direct samples. It definitely gives a good sense of how widely Puerto Ricans were listening to hip-hop and contemporary club music as they sought to synthesize their own thing. No doubt for plenty of listeners — and maybe the producers and performers themselves — such a track might even sound both "very African and very modern."

* This post first appeared on Wayne's blog Wayne and Wax. He has kindly agreed to us republishing it here.

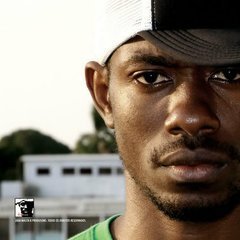

Rapping in 'Father Banana's Country'

The Angolan rap artist MCK (MC Kappa) released his third CD, Proíbido ouvir isto (Listening prohibited) in December 2011. Musically and lyrically it is his most complex and mature work yet and includes collaborations with well-known Angolan musicians of variety of genres like Paulo Flores (semba), Beto Almeida (kizomba), Ikonoklasta (rap) and Bruno M (kuduro).

Since his first album, Trincheira de ideias (Trench of ideas), MCK's m.o. has been social and political critique. "A Técnica, as causas, e as consequências" (The technique, the causes, and the consequences) circulated on candongueiros (collective transport) and in the informal market. The song exhorted listeners: "clean the dust out of your eyes/open your eyes brother/switch off TPA [official television]/tear up the newspaper and analyze daily realities." And then lamented the fact that "we have more firearms than dolls/fewer universities than discos/and more bars than libraries."

A young car washer, nicknamed "Cherokee," singing the song as he idled between jobs, was beaten to death by the presidential guard who overheard him and his body was discarded in the ocean. Divers sent to recover the corpse turned up empty handed. The body washed ashore the next day bloated and with the hands and feet still bound by bootlaces: a ringing indictment of the presidential guards' savagery. The guilty guards offered a coffin, transport and armed security for Cherokee's funeral. MCK and other like-minded rappers raised $1000 for the family and he, a university student at the time, assumed the cost of educating Cherokee's two children.

Though I don't know for sure, I would guess that some of those like-minded musicians count among those generally referred to as Angola's underground rappers – Ikonoklasta (Luaty Beirão), Keita Mayanda, Carbono Casimiro. Along with MCK they have created a brand of consciousness raising, community minded, tech-savvy, anti-commercial rap in a market with lyrics and clips awash with bling, swag and surly sisters.

Despite reports of MCK's music having been censored from play on radio stations, his first CD circulated widely via candongueiros, hand to hand and in cars. Perhaps in a nod to alleged state censorship, his second CD, Nutrição espiritual (Spiritual nutrition), pictured him in a baseball cap, with headphones on and tape over his mouth (that said, this CD was available for purchase in the gift shop at the airport). "Atrás do prejuizo," from that album, recounts the daily struggles of a student in Luanda – lack of water, strikes by professors, children begging in the streets, making a living pounding the pavement.

Like the second CD, Proíbido ouvir isto takes taboo head on. Interviewed recently in the newsweekly Novo Jornal about the new album MCK commented:

I decided to make a thematic incursion regarding various untouchable subjects and aspects of our society in order to dismantle some myths and taboos by bringing such themes as politics, religion, and race to the discussion….I took advantage of the sweet and seductive power of those things that are 'prohibited' and I invited Angola to the debate.

This new CD even caught the attention of Angola's anti-corruption campaigner Rafael Marque de Morais who wrote about it on his blog:

One of the most popular songs is "O país do Pai Banana" (The country of Father Banana – or Head of the Banana Republic) MCK describes it as tragicomedy and he and his collaborators use parody to great effect. A sampling of lyrics: "I was born here, no one fools me!" Later: "I confess, I've had it!/ I can't take it any more. I'd rather die by the bullet than of hunger/brothers, the disparities are enormous/…everything is theirs….This is the country of Father Banana." "They've made misery into a profitable business/such wealth in the hands of those who govern." And here's a state slogan followed by a popular saying which mocks disengagement: "They've transformed Angola into a 'country of the future'/ 'we'll leave everything for tomorrow' don't you think?, hahahaha!"

In the interview MCK gave Novo Jornal, the journalist asked him what dreams he had. His response is worth quoting in full:

Our elders who dreamed of Angola's independence are today living a huge nightmare. My generation doesn't want to dream anymore because to dream you first need to sleep (laughter). My generation wants to demand, wide awake, the building of a country where all of us can be proud of being Angolans.

In fact, a number of Angola's underground rappers were on the ground, mobilized and mobilizing the "32 is enough!" movement that took to the streets in March, May and September of 2011 to protest President José Eduardo dos Santos' 32 years in power.

January 31, 2012

Egyptian Post

Arguments around the affinity between art and pornography have been too frequent in Egypt recently. I have mentioned Mahmoud Amer's accusations in recent posts. Sophia Azeb has described the hysterical responses to Aliaa Elmahdy's naked self-portraits. Against the gaudy backdrop of these arguments – where conservatism and protest, Islam and Western, religion and 'secular' art are divided into predictable encampments – consider this painting by Mai Heshmat. Its her proposal for the new Egyptian stamp – now Mubarak's head has been deposed – and demonstrates a refreshing humor. The ambivalence of this woman's faceless face is suggestive of the way bodies have become canvases for political debate. Remember the logic that virginity tests were carried out by the army on female activists in order to establish that they could not claim to have been raped by the soldiers. And yet the work, veiled in colour, seems playful, even celebratory. There is something jarring in her acid green outline: it is a complex and satirical image. This is art which provokes thought without seeking to be provocative.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers