Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 294

December 7, 2016

What happens in the Democratic Republic of Congo after December 19th?

The presidential term of Joseph Kabila, in power in the Democratic Republic of Congo since 2001, is suppose to end in less than two weeks on December 19th. Kabila is barred from running for another term. The next day Congo should have a new government.

For the last year, opposition groups have demanded the electoral commission organize elections. They have mostly met with violence and obfuscation. At least 100 people have been killed in protests in 2016 and hundreds more arrested. Opposition party offices have been torched and one of the opposition candidates have been forced to flee the country. Meanwhile, Kabila’s party insist that no election can happen until 8 million potential new voters are added to the voters roll, knowing full well this could take years.

Joseph Kabila took power—he wasn’t elected; he inherited the office—in January 2001 after the assassination of his father Laurent D. Kabila while nearly half of the country was occupied by foreign troops and rebels. Among the foreign armies on the ground in the Congo, were Rwandan and Ugandan troops who earlier helped Laurent Kabila take power in May 1997. Following disagreements between Laurent Kabila and his former Rwandan and Ugandan allies who warned him against becoming too independent, the latter wound up occupying a large part of Congolese territory along with rebel groups.

The Congolese met in the South African resort, Sun City, to find a solution to the country’s crisis. They drafted a constitution accepted by referendum in December 2005 and promulgated on February 18, 2006. According to article 70 of the Constitution, the president of the republic is elected by a direct, general vote for a five year term that is renewable once. Article 220 of the Constitution is a safeguard stipulating that “… the term length of the President of the Republic” cannot be subject to constitutional revision.

In 2006, Joseph Kabila was elected for a five-year term. Before the 2011 elections, Kabila changed the rules of the game by imposing a single round of elections. This was made possible by paying large sums of money to members of the Congolese parliament. In so doing, Kabila trampled on the Congolese constitution and disregarded the separation of executive and legislative powers. The 2011 elections were particularly flawed and lacked transparency. Despite the objections by the Catholic Church of the Congo, the Carter Center, and the European Union over numerous electoral irregularities, the CENI declared Joseph Kabila the “winner.”

The country plunged into a grave political and institutional crisis. Nevertheless, the opposition expected Kabila to organize new elections at the end of his second and final term, leave power, and make way for a new president. Instead, Kabila stepped up his delay tactics in order to avoid holding elections. That’s when his excuses started. At the same time, he revived an old project to double the number of provinces, adding to the challenge of holding elections. Understanding this climate gives context to the current crisis.

There are currently two camps in conflict. On one side is the “Rassemblement,” which consists of the following political parties: the UDPS of veteran politician Etienne Tshisekedi; the G7 supporting football club owner and former governor of Katanga province, Moise Katumbi; “Congo Na Biso (Our Congo)” of Freddy Matungulu; the Dynamique de l’Opposition; and “l’Alternance pour la République.” Tshisekedi’s Rassemblement argues that Kabila is primarily to blame for the current political crisis and thus cannot take part in its resolution. Therefore, the Rassemblement is calling for “inclusive” talks to determine the conditions and means for Joseph Kabila’s departure from the presidency later this month. The Rassemblement also seeks to select an interim President until new elections can be held and seeks to find the technical and financial means for instituting a new electoral schedule and planning the next election.

On the other side are Joseph Kabila and his supporters, who want to keep the incumbent in power past December 19, 2016, in violation of article 75. Article 75 states that: “In the case of a vacancy, as a result of death, resignation or any other cause of permanent incapacitation, the functions of the President of the Republic … are temporarily discharged by the President of the Senate.” Nevertheless, the Congolese president held talks, led by African Union mediator Edem Kodjo, a Togolese diplomat, on the crisis. Only a small portion of the opposition, which included Vital Kamerhe a former ally of President Kabila and president of the Union pour la Nation Congolaise, participated in the talks. The Rassemblement did not join in the talks for several reasons, including, firstly, the rejection of Kodjo who is seen as being too close with the presidential majority; second, the government’s current judicial proceedings against Moise Katumbi, who is in exile in the United States (the government accuses him of hiring mercenaries and sentenced him, in absentia, to three years in jail for fraud); and, finally, the government’s incarceration of political prisoners and a media blackout. The Catholic Church who initially participated in the “talks” withdrew following bloody protests in September 2016.

Despite the fact that the main political parties did not participate in these talks, Edem Kodjo continued consulting with a very fringe part of the opposition and reached a “political accord” that allows Kabila to remain in power after the end of his term this year. In exchange for accepting what the Congolese people are calling “glissement,” the French word for “slippage,” Vital Kamerhe was expected to be named Prime Minister. Instead, on November 17, Kabila gave the position to Samy Badibanga, who had been excluded from the UDPS in 2012. Observers of Congolese politics note that the “political accord” reached by Kodjo and Badibanga’s nomination do nothing to resolve the country’s crisis. With the support of the U.S., the European Union, and the UN, the Catholic Church of the Congo continued engaging in consultations with the Kabila camp and Rassemblement. On December 2, the Catholic Church proposed that the presidential majority (MP) and the Rassemblement coalition meet, in a less formal setting, to discuss their differences. Such discussions would focus on adherence to the Constitution, the electoral process (including the scheduling of elections), the functioning of institutions during the transition, or what a possible political compromise might look like. Joseph Kabila visited with Catholic bishops on Monday, December 5, and the question remains whether the Congolese president will make any concessions with respect to the Rassemblement’s positions. The Catholic Church insists that this is a critical hour and has called for all parties to share responsibility and exercise good political will in order to keep the country from falling into an out of control situation. The Rassemblement is bound to spill out onto the streets on December 19 to demand that Kabila abide by the constitution and step down from office. Maman Sambo Sidikou, the head of MONUSCO, told the United Nations that there are real dangers in DR Congo’s descent into chaos.

December 6, 2016

“I will become a straight girl”

Noluvo Swelindawo.

Noluvo Swelindawo.In May 2015, Zakwe, a 28 year-old woman from Soweto, in Johannesburg, told ActionAid: “They tell me that they will kill me, they will rape me and after raping me I will become a girl. I will become a straight girl.” Earlier this week, the body of Noluvo Swelindawo, a 22 year old lesbian young woman was found discarded near the N2 highway near Khayelitsha, the largest township in the Western Cape. Noluvo was shot dead after being abducted from home and gang raped. She was known in her community for her LGBTQI activism.

Her friends are convinced she was targeted by a group of “well known thugs and gangsters in the community,” specifically because she was lesbian.

Novulo’s death was likely a homophobic hate crime and her killers are statistically likely to never be found or brought to justice (for lack of investigation).

Absolute numbers are hard to come by, but somewhere between 15 to 37.5% of South African men have admitted to raping a woman – whether an intimate partner, or a woman with whom they had no previous relationship. Basically, at best – at best – one in six South African men is a rapist. In Diepsloot, an informal settlement in northern Johannesburg, a recent study showed that 56% of men admitted to either raping or beating a woman in the last 12 months, and of these, “60% said they had done so several times over the past year.” Let that sink in: Almost four out of five had raped their first victim before the age of twenty.

One in three women (worldwide) has been beaten, coerced into sex, or otherwise abused in her lifetime.

One in three. For those of you who have a mother, a sister and a female friend all at the same time, let that sink in: one in three women has been beaten, coerced into sex, or otherwise abused in her lifetime. Maybe it’s time to start talking to each other.

In South Africa, over 25% of all women will be raped in their lifetime and 75% of all rapes are gang rapes. I am not sure that there are italics enough in the world to express what I feel about these statistics. For every 25 “men” brought to trial for rape, 24 will be acquitted. And those are just those who are brought to trial.

Here’s the testimony of Nomawabo, 30, from Limpopo, South Africa:

At school I was betrayed by my best friend. He told me to come to his house for a school assignment but when I got to the house we fought until he hit me so hard I collapsed, and then he raped me because he said I needed to stop being a lesbian. Afterwards I got pregnant and had a baby. The second time my soccer friends and I were kidnapped at gunpoint and they took us somewhere far away and did what they wanted with us for three days. We told the police but the case just disappeared. Nothing happened because they all thought I deserved it. These men are still walking free.

“The second time”…

The term “corrective rape” (as opposed to regular rape?) was introduced into the common vernacular when it became a widespread practice for (South) African males to attempt to rape the lesbian out of their victims. South Africa was the 5th country in the world to legalize same-sex marriage. For South African (and other African) lesbians, this has proved to be more of a target on their backs than a civil rights victory.

I thought he was going to kill me; he was like an animal. And he kept saying: “I know you are a lesbian. You are not a man, you think you are, but I am going to show you, you are a woman. I am going to make you pregnant. I am going to kill you” — Gaika, South Africa 2009

In their 2010/2011 Annual Report, The Triangle Project, a South African organization whose stated mission is challenging homophobia and appreciating sexual diversity, wrote this:

Our understanding is that rape is a form of gender violence that is rooted in patriarchal and heteronormative systems of control and power. Rape is a means of maintaining control and power over women and their bodies and of policing gender and sexuality norms. These norms prescribe what a woman is, how a woman should behave and stipulate that women’s bodies belong to men. It is precisely for these reasons that lesbian women in particular are targeted.

Rape is a violent, inhumane, incomprehensible abomination. If not a hate crime, it is certainly hateful. I do not subscribe to the idea that rape can be classified by circumstance or by motivation. To the victim, does it really matter if the rapist was motivated by lust and power rather than by a sick desire to change his/her sexuality? By classifying different types of rape and by extension, assigning different sentences for what is essentially the same crime, are we not introducing yet another shade of grey into a conversation that needs to be completely black and white? Responding to my question by email, Melanie Nathan, Executive Director of the African Human Rights Commission said:

These are woman who might not otherwise have been raped and these men may not have committed the rape but for the vengeance factor of the woman being a lesbian and the anger it invokes in the man. The idea of a lesbian – a woman not needing a man – often emasculates a man and so he is proving his power over her… it goes to the core of who she is. Of a perpetrator purporting to control her sexual orientation under the false notion, perpetuated by religious and cultural dogma, that she can be changed. I believe that because of rampant homophobia in some cultures and especially now in Africa and South Africa, it must be prosecuted as a specific hate crime.

I disagree. I believe that making distinctions based on the motive of a specific rape muddies the waters. All rapes are about the subjugation of women and men trying to assert their physical and sexual superiority over women. Yes, being a lesbian (a population already living through social discrimination) certainly adds a layer of “motivation” for these rapists, but so does wearing a short skirt, or being flirtatious, walking down a street, rejecting a man’s advances or breathing while female.

In South Africa, between 15 – 37.5% of men admit to intercourse with a woman without consent and 1 in 4 women have been raped (and those are the women we know about). Perhaps lesbians are more at risk than heterosexual women (there isn’t enough research to say definitively), but with those statistics, is that difference in risk significant enough to justify a separate class of rape and the subsequent clouding of the conversation and dilution of law enforcement that comes with it? There is no such thing as “corrective rape;” there is nothing about rape that is correct.

“Corrective” rapists are motivated by the idea that homosexuality is “unnatural.” We should be teaching African boys (and shouting it from every rooftop) that every rape is inarguably unnatural, that the perpetrator forfeits their membership in the human family and is worthy of maximum punishment.

“I Will Become A Straight Girl”

Noluvo Swelindawo.

Noluvo Swelindawo.In May 2015, Zakwe, a 28 year old woman from Soweto, in Johannesburg, told ActionAid: “They tell me that they will kill me, they will rape me and after raping me I will become a girl. I will become a straight girl. Earlier this week, the body of Noluvo Swelindawo, a 22 year old lesbian young woman was found discarded near the N2 highway near Khayelitsha, the largest township in the Western Cape. Noluvo was shot dead after being abducted from home and gang raped. She was known in her community for her LGBTQI activism.

Her friends are convinced she was targeted by a group of “well known thugs and gangsters in the community,” specifically because she was lesbian.

Novulo’s death was likely a homophobic hate crime and her killers are statistically likely to never be found or brought to justice (for lack of investigation).

Novulo’s death was likely a homophobic hate crime and her killers are statistically likely to never be found or brought to justice (for lack of investigation).

Absolute numbers are hard to come by, but somewhere between 15 to 37.5% of South African men have admitted to raping a woman – whether an intimate partner, or a woman with whom they had no previous relationship. Basically, at best – at best – one in six South African men is a rapist. In Diepsloot, an informal settlement in northern Johannesburg, a recent study showed that 56% of men admitted to either raping or beating a woman in the last 12 months, and of these, “60% said they had done so several times over the past year.” Let that sink in: Almost four out of five had raped their first victim before the age of twenty.

One in three women (worldwide) has been beaten, coerced into sex, or otherwise abused in her lifetime.

One in three. For those of you who have a mother, a sister and a female friend all at the same time, let that sink in: one in three women has been beaten, coerced into sex, or otherwise abused in her lifetime. Maybe it’s time to start talking to each other.

In South Africa, over 25% of all women will be raped in their lifetime and 75% of all rapes are gang rapes. I am not sure that there are italics enough in the world to express what I feel about these statistics. For every 25 ‘men’ brought to trial for rape, 24 will be acquitted. And those are just those who are brought to trial.

Here’s the testimony of Nomawabo, 30, from Limpopo, South Africa:

At school I was betrayed by my best friend. He told me to come to his house for a school assignment but when I got to the house we fought until he hit me so hard I collapsed, and then he raped me because he said I needed to stop being a lesbian. Afterwards I got pregnant and had a baby. The second time my soccer friends and I were kidnapped at gunpoint and they took us somewhere far away and did what they wanted with us for three days. We told the police but the case just disappeared. Nothing happened because they all thought I deserved it. These men are still walking free.

“The second time”…

The term ‘corrective rape’ (as opposed to regular rape?) was introduced into the common vernacular when it became a widespread practice for (South) African males to attempt to rape the lesbian out of their victims. South Africa was the 5th country in the world to legalise same-sex marriage. For South African (and other African) lesbians, this has proved to be more of a target on their backs than a civil rights victory.

The term ‘corrective rape’ (as opposed to regular rape?) was introduced into the common vernacular when it became a widespread practice for (South) African males to attempt to rape the lesbian out of their victims. South Africa was the 5th country in the world to legalise same-sex marriage. For South African (and other African) lesbians, this has proved to be more of a target on their backs than a civil rights victory.

I thought he was going to kill me; he was like an animal. And he kept saying: ‘I know you are a lesbian. You are not a man, you think you are, but I am going to show you, you are a woman. I am going to make you pregnant. I am going to kill you– Gaika, South Africa 2009

In their 2010/2011 Annual Report, The Triangle Project, a South African organisation whose stated mission is challenging homophobia and appreciating sexual diversity, wrote this:

Our understanding is that rape is a form of gender violence that is rooted in patriarchal and hetero-normative systems of control and power. Rape is a means of maintaining control and power over women and their bodies and of policing gender and sexuality norms. These norms prescribe what a woman is, how a woman should behave and stipulate that women’s bodies belong to men. It is precisely for these reasons that lesbian women in particular are targeted.

Rape is a violent, inhumane, incomprehensible abomination. If not a hate crime, it is certainly hateful. I do not subscribe to the idea that rape can be classified by circumstance or by motivation. To the victim, does it really matter if the rapist was motivated by lust and power rather than by a sick desire to change his/her sexuality? By classifying different “types” of rape and by extension, assigning different sentences for what is essentially the same crime, are we not introducing yet another shade of grey into a conversation that needs to be completely black and white? Responding to my question by email, Melanie Nathan, Executive Director of the African Human Rights Commission said:

These are woman who might not otherwise have been raped and these men may not have committed the rape but for the vengeance factor of the woman being a lesbian and the anger it invokes in the man. The idea of a lesbian – a woman not needing a man – often emasculates a man and so he is proving his power over her… it goes to the core of who she is. Of a perpetrator purporting to control her sexual orientation under the false notion, perpetuated by religious and cultural dogma, that she can be changed. I believe that because of rampant homophobia in some cultures and especially now in Africa and South Africa, it must be prosecuted as a specific hate crime.

I disagree. I believe that making distinctions based on the motive of a specific rape muddies the waters. All rapes are about the subjugation of women and men trying to assert their physical and sexual superiority over women. Yes, being a lesbian (a population already living through social discrimination) certainly adds a layer of “motivation” for these rapists, but so does wearing a short skirt, or being flirtatious, walking down a street, rejecting a man’s advances or breathing while female.

In South Africa, between 15 – 37.5% of men admit to intercourse with a woman without consent and 1 in 4 women have been raped (and those are the women we know about). Perhaps lesbians are more at risk than heterosexual women (there isn’t enough research to say definitively), but with those statistics, is that difference in risk significant enough to justify a separate class of rape and the subsequent clouding of the conversation and dilution of law enforcement that comes with it? There is no such thing as ‘corrective rape’; there is nothing about rape that is correct.

‘Corrective’ rapists are motivated by the idea that homosexuality is ‘unnatural’. We should be teaching African boys (and shouting it from every rooftop) that every rape is inarguably unnatural, that the perpetrator forfeits their membership in the human family and is worthy of maximum punishment.

‘Corrective’ rapists are motivated by the idea that homosexuality is ‘unnatural’. We should be teaching African boys (and shouting it from every rooftop) that every rape is inarguably unnatural, that the perpetrator forfeits their membership in the human family and is worthy of maximum punishment.

December 5, 2016

The grapes of wrath

Image Credit: Lotte La Cour

Image Credit: Lotte La Cour“For me personally, it seems as if modern day slavery is practiced on many farms, and the farmworker is almost viewed as ‘the property’ of the employer.” These words are not mine, but those of a prominent member of the wine industry, and they represent the culmination of a long and arduous research into the South African wine industry.

The South African wine industry contributes R36 billion (US$2,5 billion) to the South African national budget. It has seen booming exports in recent years, especially to Scandinavia, where the rise in imports of South African wine has increased by 78 % in Denmark alone in just 10 years. In Sweden, South African wine has been second or third in wine sales for years, often outselling French wine. Annually, we Scandinavians drink more than 50 million liters of wine.

But despite this apparent success, there are grim, but well hidden realities of the wine industry that have been ongoing for many years. So, perhaps South Africans needed a foreign journalist to show them just how bad it is.

Bitter Grapes UK Trailer

The nasty truths about how wine is produced in South Africa are not new, and the South African wine industry has been warned repeatedly about abuses occurring across vineyards in wine producing areas of the country. In 2011, Human Rights Watch published a report, “Ripe with Abuse,” that focused on the same issues that my film dealt with, and four years later, the ILO published an equally damning report. Both reports were serious critiques of the working and living conditions of South African farm workers. Several local and foreign NGOs and unions have addressed the same issues.

Yet, these reports failed to make headlines in Scandinavia and South Africa. In December 2015, I traveled with a film crew to the Western Cape province to document conditions on farms — filming and interviewing workers. We were commissioned by three Scandinavian public service broadcasters in Denmark, Sweden and Norway, and also partly funded by the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs through the Danish international development agency, DANIDA. In total we made three trips to the area.

In anticipation of our arrival for the last of these trips in June 2016, a so-called heads-up warning was sent to 133 stakeholders in the industry accusing of us putting “…unethical questions to workers and changing the angle to a negative.”

Indeed, we were asking critical questions, not only to the various farm owners and industry bodies, but also to the Wine and Agricultural Ethical Trade Association (Wieta). This is an organization which has almost half of all wine producers in South Africa as members, and an organization that many Western importers and consumers must rely on to ensure that the wine we buy is produced under reasonable conditions.

Their label, “Certified Fair Labour Practice,” adorns many bottles and pap-sacks (wine in plastic containers) on supermarket shelves in Scandinavia. But is a label that is issued by an organization whose board gives the industry a majority say, a guarantee that everything is fine?

Or is it as a former member of its board writes in an internal e-mail to the board:

“…We clearly have a case of power imbalances at play here and producers, especially those with deeper pockets, seem to think they own Wieta as their marketing tool.”

This was just one of many e-mails we obtained, following a final meeting with two top-executives from the wine industry. A meeting that was ultimately fruitless, as all the involved farm owners and their industry bodies refused to be interviewed on camera and told us openly and frankly that we were wrong. They even refused to shake our hands in parting, instead sending us off with the words: “You are a disgusting piece of rubbish.”

After a couple of months of editing, the documentary was aired in Sweden and Denmark in October and in Norway in November. This was when the metaphorical explosion began, and conditions in the South African wine industry suddenly began making headlines around the world.

In addition to the many critical points about the working and living conditions among the approximately 100,000 permanent farm workers struggling to survive in the South African vineyards, the documentary also explores how a rapidly growing number of migrant workers from countries such as Lesotho and Zimbabwe ended up at the bottom of the global labor pyramid. Desperate workers live in cardboard houses, with families and children back home who are trying to survive on four US dollars a day. Not an easy task, given that four dollars a day is half the absolute minimum wage in South Africa.

But they have no choice and they have no voice, especially since only a very few are members of a union. Many don’t even have a work permit and most don’t even know if there is room for them on the back of the labor broker’s truck or bakkie the next morning.

Another alarming thing that the documentary unveiled was the gruesome heritage of the Dop-system, where workers are paid in alcohol instead of money. This system was banned in 1960, but according to researchers at various South African universities and organizations, the Dop-system still exists today, just in other forms, where farmers allow alcohol-dependent workers to buy alcohol on credit. As a result, South Africa has one of the world’s highest levels of children born with Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS), with more than 60,000 children born with severe brain damage annually, a condition they will have to live with for the rest of their lives.

We met several of these children, both on the farms and in crèches. One of them was Robyn. She is ten years old, but has the mental development of a child aged four or five. Luckily, she is now in good hands with a foster mother, but thousands of other children like her are not so lucky and face an uphill struggle in life.

After having made headline news for weeks (see here, here, here and here), and after the industry has done its best to “shoot the messenger boy” by claiming that the documentary is “biased” and “one-sided,” both local and national governments intervened.

Recently there were unannounced inspections at five of the farms that we visited in the documentary, and as a result of these inspections, all five farms were served legal notices to improve the conditions of their workers. Some of the breaches include that housing was illegal, the official Health and Safety Act was violated, and that workers had not been trained or equipped with the necessary protective clothing when using hazardous pesticides that for many years have been totally banned in Scandinavia. One of the farms was also in breach of the national wage policy.

The authorities have promised that many more farms will be inspected in the future. Is this good news for the farm workers? Will the wine industry and its respective bodies understand that Apartheid is over and that they must treat the workers as they would like to be treated themselves? Will the Danish, Swedish and Norwegian state-owned retailers and supermarket chains understand that their ethical values and Corporate Social Responsibility policies are more than nice words on a piece of paper.

In the management buzzword dictionary, this is referred to as to “walk the talk.” I would advise the South African wine industry to tie their shoe laces and start walking, and to be assured that we will be hot on their heels for the duration of the journey.

December 3, 2016

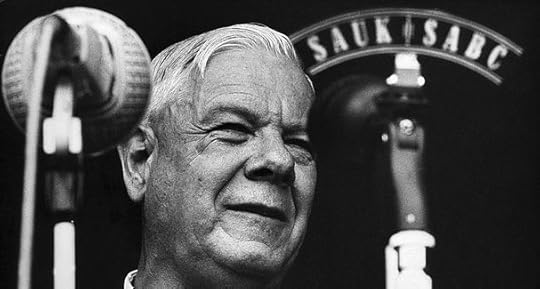

Inheritances of our fathers

There’s History, with a capital ‘H’ – the one you find written up, memorized and recited as facts, dates, inaugurations, wars, victims and statistics. And then there is the one in small caps – the history that gets under your skin: when great political systems are embodied in the tiny details of everyday life; when policies made in the soft cushions of parliaments have a devastating impact on your daily lived experience; when great power struggles are mimicked in the blood and guts of the most intimate of relationships.

Three recent books about South African history display the latter version: Marianne Thamm’s autobiography Hitler, Verwoerd, Mandela and Me: A Memoir of Sorts, Bill Nasson’s History Matters: Selected Writings, 1970-2016 and Wilhelm J. Verwoerd’s edited collection of tributes to his father, Verwoerd: Só onthou ons hom (“Verwoerd: This is how we remember him”). In all three these books we see History echoed in the personal histories of people, their relationships, and their life choices.

The title of Marianne Thamm’s autobiography already places her next to three great historical figures of the twentieth century. The shadow of Adolph Hitler falls across her childhood, Hendrik Verwoerd’s ghost stalks her adolescence and adulthood, and then, finally, Nelson Mandela’s legacy brings her the hope she needs to keep going in this bleak, bewildering, beloved country.

Throughout Thamm’s life she has been wrestling with the legacy that she inherited. Until shortly before the death of her father, Georg, Thamm struggles to make peace with his Nazi past and his apparent inability to adapt to a changing South Africa. Initially the constant repetition of her daughterly rebukes becomes somewhat jarring, as if the reader is brought in to observe a personal therapy session. In the former Nazi Jugend member, Thamm sees a manifestation of the intolerance, racial supremacy and ethnocentrism that diagonally oppose the values she has pursued as journalist and activist. But gradually the reader comes to realize that this relationship between child and father also serves as a larger metaphor for the continuing struggles of a younger generation of white South Africans to come to terms with their political and cultural inheritance – the historical guilt, or at least collective responsibility, they carry with them.

Thamm’s ability to tell a story is what made her a respected and popular journalist. The anecdotes of her adolescence in the suburbs, the fumbling discovery of her sexuality, and her hesitant first steps into motherhood are told with compassion, insight and self-deprecating humor, and are bound to resonate with many readers who have had similar experiences. But it is her ability to contextualize these personal experiences within the racist, homophobic, and paranoid South African society that imbues them with a much broader resonance.

A similar ability to make links between seemingly everyday events and the bigger historical maelstrom one finds in Bill Nasson, even though his is a more academic register than Thamm’s. Nasson, a historian who has taught at the Universities of Cape Town and Stellenbosch, is a historian to the bone – someone who constantly experiences the present through the prism of the past, for whom the smallest of daily experiences are projected onto the large canvas of history. His anthology is an enjoyable assortment of scholarly articles, book reviews and personal recollections. His own teenage years are drawn upon to take stock of the ideals of non-racialism, while the Leitmotiv of resistance to oppression is woven through chapters on historical figures, such as Abraham Esau, a Coloured blacksmith from Calvinia who died cruelly at the hand of marauding Boers during the South African War, and in the drawing of historical comparisons such as the one between the 1916 resistance in Northern Ireland and the Boer rebellion. Culture and politics are close companions throughout, and even braaiing and cricket form part of the passing parade. Nasson also reflects on the discipline of historical writing itself, and laments the inability of many historians to make history come alive in accessible language. This is not a limitation Nasson himself suffers from.

A stark contrast to the relationship between Thamm and her father emerges in the anthology (in Afrikaans) about Hendrik Verwoerd, edited by his son (who, in his foreword, takes issue with the “clichéd accusations of Nazism, racism, anti-Semitism and more”). The book, an updated version of a commemorative collection from 2001, has now been republished with additional contributions to mark the 115th anniversary of his birth and the 50th of his death. The anthology does not attempt to provide any critical perspective, serving rather as a hagiography aimed at painting a picture of a strict, but humane “Doctor,” who could provide rational grounds for his policies of racial discrimination. You have to pinch yourself to realize that you’re actually reading this rose-tinted remembrance of Verwoerd in the year 2016, without so much as a hint of irony.

Whether anecdotes of Verwoerd as a patriarch – who chastises his son because his friend showed up at the official residence in shorts, or who gives his grandson a spoonful of sharp mustard in order to end his insistence to play with the condiments on the table – succeeds in bringing to life a kinder persona than the one associated in the history books with the design of Apartheid, is for the reader to decide. But what does feel like a historical slap in the face is the thinly veiled attempt at ameliorating Verwoerd’s legacy through a reflection on his intelligence and upright personality, as if to suggest that history judged him unfairly. After all, “Doctor didn’t easily make a mistake” (p. 283).

Tell that to Thamm’s adopted daughters, for whom racism, skeptical looks and uncomfortable questions have been part of their experiences growing up. It is in those casual comments at the nursery school, those stares at the supermarket, and in the unchecked callousness of friends that one once again hears the echoes of great historical narratives resound through the small dramas of the everyday. In his son’s eyes, Verwoerd might have been a good father and a family man, but that doesn’t make the smallest of dents in his political and social legacy. No amount of banal tales of how he interacted with his family, colleagues or friends can undo the indisputable historical fact that he was the architect of an evil system of which the tentacles can still be felt today in every aspect of our public and private lives. There is a line by the Afrikaans poet D.J. Opperman that, roughly translated, goes: “always remember, around your actions borders an eternity.”

History, as told by these three authors, reminds us that the past is not something that can or should be left behind. Rather, as History echoes in the histories of our daily lives – in the supermarket, at the pre-school, on the cricket pitch, beside the fire at a braai – we are morally obliged to keep reflecting on them. Didn’t a verse in the old Nationalist anthem Die Stem ask for the inheritances of our fathers to remain inheritances to our children?

Be careful, as they say, what you pray for.

This is an edited version of a piece that first appeared in Afrikaans in the Media24 publication Rapport.

December 1, 2016

Memory of the Present

Every time I visit the prison, I try to notice as much as possible. The attitude of each of the guards I meet as I go through the different levels of security, the names on the form that show how many visitors arrived before us, the words on the faded notices – printed and handwritten – along the way, how much sky shows between the windows and bars and walls, the sound of buzzing that releases the heavy steel gate and its banging behind us so the guards can hear it click shut, the posture of the inmates’ bodies in the big room where we all sit, everything controlled and everything subtly revealing.

This is what I think about on December 1st these days. Though many of us do not mark the day, on December 1st 182 years ago the institution of slavery was abolished in the colonies that made up South Africa.

Slavery was a prison the size of the world.

It made us not human while building a definition of the human out of those who enslaved us. As a result, to be human was to be not us. And the brutality that exclusion unleashed against us made the world we still live in today.

In the past we tried to forget slavery just to abolish the enormity of its violence against us. But, as Audre Lorde said in another place of slavery and about another kind of silence, forgetting does not protect us.

So we must urgently remember. Slavery and its legacy is a deep well, and we climb out of its steep walls slowly. Enslaved people built the economy of the early South African colonies. This is so indisputable that dominant culture can benignly afford to recall slavery as part of a vaguely picturesque past that left us with beautiful colonial houses, award-winning wines and tourism. A form of forgetting, in other words.

But on every one of those estates, the slave bells and the slave quarters summon a hidden history like bones protruding from the ground. In reality, slaves brought from East Africa, India and South East Asia formed the majority of the population of the Cape Colony and every aspect of colonial society relied on the daily brutality of those stolen bodies and their stolen labour. The Slave Lodge in central Cape Town, now a haunting museum of slavery, was also the main brothel of Cape Town. To be enslaved was to be treated with daily, intimate and public violence for 176 years.

The memory of that violence hovers over us like a threat and yet is also used against us in a cruel sleight of hand as evidence of our inhumanity, the way women are accused of being responsible for the sexual violence against them. The legacy of slavery is in the normalization of violence against certain people, as is clear in our rates of sexual violence, poverty, unemployment and incarceration. For whom are such figures normal, inconsequential, no national crisis?

So that is why we need to take hold of this past. But is remembering apartheid 22 years after the transition is not enough? Yes, apartheid is more than enough, but apartheid took its grammar, logic and laws, like the pass system, from slavery and the colonial period.

Two of the men across two generations in my family have been in prison, that I know of. Some things you don’t speak about. I think of them when I’m signing in to visit another woman’s son. Apartheid’s focused violence, poor schooling, poverty, the moral violence of patriarchy and the availability of drugs seemed to make their path to jail almost inevitable, and the shame caused the rest of us to draw our boys and girls closer, protect them more, and watch the world continue as it does. African American scholars who study the aftermath of slavery in the US argue that the institutions of state that were built by a slave-holding society adapted to abolition as simply new conditions for forced labour. They call this the Prison-Industrial Complex and the School-to-Prison pipeline, which today delivers more Black men to prison than higher education. They are calling for a new abolition.

They say that clanging sound reverberating around us is the world still shaped like a prison.

November 29, 2016

Is your mobile phone company seeing like a state?

In September 2014 streams of people flowed into Kenya’s largest stadium, located a few miles from downtown Nairobi on the much-celebrated Thika Superhighway. This arena is typically host to major sporting events and political speeches; Barack Obama recently addressed “the Kenyan people” there. But on this day, it was the site of a more unorthodox event. The crowds, dressed in their Sunday best, disembarked from their buses and walked toward the grounds, now peppered with new signage. The first of these gave a hint of what was to come: a large billboard identifying the destination as Safaricom Stadium Kasarani.

The occasion was the 2014 annual shareholder meeting for Safaricom, a mobile network provider that is the country’s largest and most profitable company. Like other publicly traded corporations around the world, Safaricom stages this yearly event as an occasion to distribute information and receive feedback. It invited shareholders to celebrate their company’s successes, critique its perceived failures, and weigh in on the policies that will drive the corporation’s strategies in the year to come.

But if annual shareholder meetings are a global form, Safaricom’s meeting was particularly Kenyan. On that September day, the signs of the corporate body and the signs of the body politic were brought together in a way that distilled a doubling of meaning increasingly common in Kenya, where Safaricom holds considerable cultural cachet, political import, and economic significance. Every few feet, as the national anthem played, one was confronted by Safaricom’s telltale green logo. Although this marketing blankets the country—across billboards, shops, and news media—within the stadium it existed in telling cohabitation with a highly charged symbolic palette: the forest green, blood red, and dark black of the Kenyan flag. Most strikingly, the “Kenyan green” of the flag—which symbolizes the land lost to white settlers, gained through decolonization, and subsequently the source of (sometimes violent) ethnic politics—was juxtaposed against a green of a lighter hue. This shade, Kenyans will tell you, is “Safaricom green.”

If the iconography of the stadium sought an uneasy conviviality between Kenyan nationalism and commercial branding, there were also indications of a more thorough entanglement. The stadium itself, a historically important sign of independent Kenya, had only recently received its corporate name, which came on the heels of Safaricom’s large injection of capital to revive the site. In a few discreet places, however, the old name remains in a smaller, red font: Moi International Sports Centre. It is the name of Daniel Arap Moi—the strongman who ruled Kenya for nearly a quarter of a century—that previously greeted citizens’ arrival at this venue of national and sporting spectacle. Today both he and a state that once seemed omnipresent are sidelined, their importance mediated by a company that, as one informant told us while patting his pocketed phone, “has an intimate relationship with millions of Kenyans.”

In his influential account of the aesthetics of postcolonial power, Achille Mbembe emphasizes its banality: it is through the everyday proliferation of an autocrat’s presence—through required portraiture, inscriptions on currency, and ubiquitous media coverage—that political hierarchies are reproduced. Through the mobilization of national symbols and corporate iconography, Safaricom today is replicating such patterns of statecraft. Although the resulting formation differs in important ways from the dictatorial regimes studied by Mbembe, a close examination of Safaricom’s operations in Kenya reveals how new configurations of capital and politics shape life in Kenya today. It is not only through advertisements that Safaricom impresses its symbolic order upon Kenya—though it does so considerably—it is also through the pomp and circumstance of new store openings, the sponsorship of cultural events and philanthropic initiatives, and the routine use of text messages to remind, nudge, and discipline users. Tracing the stylistics of Safaricom’s power reveals more than the aesthetic registers at play in Kenya. It demonstrates how corporations—often in close relationship with states—are able to shape the intimacies and banalities of everyday life in Kenya and elsewhere.

Safaricom is not just another mobile phone company. Both in Kenya and abroad, Safaricom has carved out a conceptual and material presence that far outweighs such a generic description. Across the world, it is widely lauded for its innovations, most notably the mobile money transfer service M-Pesa, which today is used by 20 million Kenyans. Within the country it is the most profitable company and largest taxpayer. By most accounts, Safaricom was established in 1997 as a subsidiary of the parastatal Telkom; in 2000, the United Kingdom-based Vodafone acquired 40% of the shares and the authorization to autonomously manage the firm. Today, the government maintains a 35% share, while the rest is traded publicly on the Nairobi Securities Exchange (NSE). In addition to providing mobile infrastructure to nearly 70% of Kenyans and many government offices, Safaricom was tasked with building a multimillion-dollar surveillance system for Kenya’s national security apparatus in 2014. But one regulator gave perhaps the best summary of its importance: if Safaricom’s network goes down, he told us, “everything else stops.”

The unwieldy entangling of this multinational corporation and the postcolonial state are refiguring notions of citizenship and bringing Safaricom into a direct, even intimate, relationship with Kenyans. Many Kenyans will tell you, with a hint of pride, that their countrymen are “peculiar,” and Safaricom invests considerably in the cultural work of fitting this distinctiveness. In doing so, Safaricom has established itself as a corporation deeply attuned to a national milieu, in large part through the calling forth of Kenyan publics as new markets. Put another way, as it extends its infrastructures to a growing body of paying customers, Safaricom invokes a seemingly noncommodified public: the nation.

Consider an example. In dialogue with a wider network of development aid organizations and researchers, Safaricom invests considerably in multiple forms of market research, much of which resembles the fine-grained knowledge work associated with ethnography. Indeed, the company routinely attributes its success to its capacity to map vernacular practices and preferences in a bid to simultaneously create new markets and secure the “public good.” Many of its commercial innovations rely upon this acuity. For example, an oft-cited early success was Safaricom’s proactive cultivation of cash-strapped users through the introduction of per-second billing. More famously, the employees credited with designing M-Pesa initially imagined it as a microcredit repayment scheme; it was only by monitoring the unexpected behavior of the pilot populations that M-Pesa became what it is today: a person-to-person money transfer service, mimicking in digital form the already existing networks of domestic remittance (Morawcyznski 2009). Cultural expertise is thus generative of new forms of commercial infrastructure that many see as crucial to Kenya’s vibrant future as the continent’s “Silicon Savannah.”

In other cases, Safaricom engages in practices and invokes idioms with long genealogies in Kenya’s patrimonial politics. For example, if the 2014 shareholder meeting was a performance evocative of Kenyan politicking, this was a staging borne of criticism. In preparation for the first shareholder meeting in 2009, Safaricom announced that the cost of providing lunch, printed documents, and branded gifts for the thousands of expected attendees was prohibitively high. Shareholders reacted vocally. As one wrote to the Daily Nation, not providing free lunch was a sign of “disrespect”:

I have an issue with the contention that [these shareholder meetings] “are not social events.” This view is snobbish; what’s wrong with mixing business with interaction? Don’t managers routinely meet at leisure spots to do business while partaking of fun and food? Are ordinary shareholders lesser investors?

Here, the author was drawing on an enduring expectation in Kenya (as elsewhere) that solidarities in business or politics be marked through gift exchange. If this has been most evident historically in political rallies and electioneering, it is an idiom that readily incorporates Safaricom. These, in other words, were critiques emanating from a public conceiving itself in the registers of both shareholders and citizens.

Safaricom has learned in the years since how their shareholders expect to be treated. When they entered the stadium in 2014, attendees were provided a boxed lunch and a Safaricom T-shirt. Investors expressed approval. One gentleman rose to ask about financial accounting but received applause for beginning his question by congratulating the company for becoming attuned to shareholders’ expectations: “Mr. Chairman, we have been entertained today. We have had transport, we have had some lunch, we have had some giveaways. This meeting is a big improvement in the history of Safaricom. Thank you very much. Asante sana. Asante sana.”

It is a common—and justifiable—fear that the privatization of infrastructure removes the capacity of citizens to make demands upon providers; the case in Kenya, however, suggests more subtle processes are at play. While Kenyans are first and foremost customers of Safaricom, more than half a million of them are also shareholders. Moreover, and because Safaricom’s corporate strategy includes national branding, sometimes these publics make their critiques not as shareholders or customers: they make their claims as Kenyan nationals, demanding the company acknowledge theirs as a relationship of reciprocal obligation and respect.

While Safaricom relies on foreign capital, expertise, and infrastructure, our emphasis on the peculiarity of Safaricom belies any straightforward notion that the liberalization of markets and the privatization of infrastructure engender a deterritorialized, homogenous space of flows. Instead, the formation of capitalism visible in Kenya relies on nuanced translations and heterogenous forms of capture. This puts the historical and cultural specificity of place at the center of Safaricom’s ability to generate profits.

It also means that Safaricom reflects and responds to ideas about the social good and public interest that are both firmly embedded in Kenya and circulating globally in development thinking and corporate strategizing. One of the crucial ways this plays out is through Safaricom’s extensive investment in corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives. Like many companies, Safaricom has a philanthropic foundation that provides goods traditionally considered the responsibility of modern states: education, health services, clean water. And it is important to note many Kenyans expect Safaricom to step in to provide services that the Kenyan state is either unwilling or unable to provide. As one Safaricom employee told us, when something terrible happens, people ask, “What is Safaricom doing” to help? Through CSR, in other words, Safaricom engages in state-like actions.

Globally, CSR is now big business, but it is not always good business. Instead, it is often seen as a necessary expense stemming from relatively selfless commitments to philanthropy or an interest in managing public image. In Safaricom’s case, however, CSR and core commercial services often exist in a zone of indistinction: what qualifies as philanthropy and what qualifies as business is not always obvious. For example, their enormously successful and profitable mobile money transfer service, M-Pesa, was originally promulgated as a CSR initiative. For a contemporary development industry that sees connectivity as a human right, simply selling airtime bundles is framed as a means of securing the public good. For Safaricom, however, while this indistinction requires vigilant management, it is not a problem to be solved, but rather a strategic stance. It is through the work of “building communities” and “transforming lives” that new markets and new profits result.

CSR is concurrently a global corporate strategy and a means of more firmly embedding Safaricom within a particularly Kenyan milieu. However, proximity to Kenyan particularity can be a liability for the company. Although Safaricom can parlay its state-like actions into profits, it cannot predict how Kenya’s multiple publics will register their claims and critiques. In a country where the reach of infrastructures often maps onto ethnoregional patterns of stratification, Safaricom’s role as provider of infrastructures and services—its state-like actions—are always open to accusations of engaging in ethnic politics. This happens in ways significant and mundane: the public even scrutinizes promotional giveaways for signs of ethnic favoritism, requiring Safaricom’s CEO to publicly insist on the company’s objectivity. It is Safaricom’s efforts to manage these contradictions to which we now turn.

If Safaricom’s importance in Kenya suggests the emergence of something like a corporate state, it is a stature dependent on the savvy enactment of corporate nationhood. Understood as a unifying, emotional bond, nationalism has a precarious status in Kenya. Often loyalties are more circumscribed, leading to moments of intense fragmentation along the lines of ethnicity, or what John Lonsdale calls “political tribalism.” As Safaricom seeks to don the mantle of the nation, its position is similarly fraught, but the company does much to address this. For example, other large corporations in Kenya are considered biased due to their management’s ethnic affiliation. Safaricom, in contrast, employs foreign management to avoid accusations of favoritism. In its public performances, too, it does its best to present itself as an undifferentiating national force, such as in its advertisements, which soar through landscapes of natural vitality and human productivity.

In both cases, it is through a strategy of distance from certain aspects of Kenyan business and politics that Safaricom seeks to achieve a national identity unencumbered by the ethnic politics that have characterized postcolonial Kenya. Thus, although we argue here that Safaricom relies on an intimate relationship with Kenya’s distinctiveness, that relationship is calibrated to maintain a distance from some of Kenya’s more divisive aspects. Indeed, maintaining this distance is critical to its profit-making capacities.

Safaricom’s success in Kenya is widely celebrated as an emblem of “Africa rising,” an aphorism that signals an end to “the hopeless continent,” its patronage politics, and the uneven service delivery that are said to beleaguer the continent’s progress. Less noted, however, is how Safaricom’s success has been dependent on the uneasy management of the dialectics of intimacy and estrangement, of proximity and distance. It is by working these unwieldy middle grounds that new relations of power among “the public,” “the private,” and “the philanthropic” become visible. It is here that the lines between market making and the public good, enacted through infrastructure, come to the fore and change the terrain on which Kenyans can make claims for services, redistribution, and recognition.

This post was first published on Limn. It is republished here with kind permission of the editors.

November 26, 2016

VIVA FIDEL!

If Africa is a country, then Fidel Castro is one of our national heroes.

After fronting the Cuban revolution against a corrupt, American-sponsored dictatorship in 1959, Cuba under Fidel worked hard to develop its own distinct foreign policy independent from its more powerful neighbor, the United States, or its supposed ally, the Soviet Union. Africa became central to that foreign policy. For me, and people of my generation, Fidel Castro entered our consciousness as a hero of our liberation. He wasn’t just fighting for an abstract cause. He was literally fighting for us.

One of Castro’s central foreign policy goals was “internationalism” – the promotion of decolonization and revolutionary politics abroad. This involved sending troops to fight in wars against colonial or proxy forces on the African continent, as well as supporting those movements with logistics and technical support. Cuba sent troops, but it also sent tens of thousands of Cuban doctors, dentists, nurses, health-care technicians, academics, teachers and engineers to the continent and elsewhere. That a significant proportion of Cubans trace their ancestries to West and Central Africa (owing to slavery) contributes to this politics. It is important to note that critics of Cuba have pointed to the paradox of this policy: while Cuba has a progressive foreign policy on race, at home Afro-Cubans have often been at odds with the Communist Party’s failure to reflect the full range of Cuba’s racial diversity in its leadership structures or to fully address race politics. Nevertheless, this doesn’t detract from Cuba’s Africa policy.

Cuba’s involvement in Africa started with the Congo (later renamed Zaire and now the Democratic Republic of Congo or DRC) following the murder of Congo’s first prime minister, Patrice Lumumba, by a conspiracy of western intelligence agencies (the strong hand of former Belgian rulers), and local elites. In 1964 Castro sent his personal emissary, Che Guevara, on a three-month visit of a number of African countries, including Algeria, Benin, Ghana, Mali, Guinea, Congo-Brazzaville and Tanzania. The Cubans believed that there was a revolutionary situation in Central Africa, and they wanted to help, argued historian Piero Gleijeses, who studied Cuba’s Cold War foreign policy in his books, Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington, and Africa 1959-1976 and Visions of Freedom: Havana, Washington, Pretoria, and the Struggle for Southern Africa 1976-1991. Crucially, Guevara established relations with the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), then based in Congo-Brazzaville. In 1965 Cubans instructors trained MPLA fighters to fight Portuguese colonialism. Later that year, Guevara and a group of exclusively black Cubans joined Lumumbaists, led by Laurent Kabila, in a revolt against Mobutu Sese Seko’s government (then backed by South African and Rhodesian mercenaries). This revolt was crushed due to a mix of factors: naiveté, unpreparedness, and the poor quality and lack of commitment of Kabila and his men.

Successes did follow elsewhere, however. Even as Cuba’s intervention struggled in Congo, Amilcar Cabral, leading a guerrilla struggle against Portuguese colonialism in Guinea Bissau and Cape Verde, asked for Cuban assistance. Between 1966 and 1974 a small Cuban force proved pivotal in the Guineans’ victory over the Portuguese. Following the Carnation Revolution in Portugal in 1974, Guinea-Bissau finally won independence. This time Cuba’s involvement also stretched to medical support (Cuban doctors) and technical know-how. After shifting their to Guinea-Bissau and Capo Verde, the Cubans were critical to the MPLA’s success in taking the capital city of Luanda and declaring independence on November 11, 1975.

Cuba’s involvement in the freedom of South Africa from white minority rule was even more dramatic. Twice – in 1976 and again in 1988 – the Cubans defeated a US supported proxy force of the South African Apartheid army and Angolan “rebels;” these instances were the first times South Africa’s army was defeated, a humbling experience that the Apartheid regime’s white generals still have trouble stomaching in retirement.

As Gleijeses told Democracy Now! in December 2013, at the time of Mandela’s passing, black South Africans understood the significance of these defeats. The black South African newspaper, The World, wrote about the 1975 skirmishes: “Black Africa is riding the crest of a wave generated by the Cuban victory in Angola. Black Africa is tasting the heady wine of the possibility of achieving total liberation.” Gleijeses remembered how Mandela wrote from Robben Island: “It was the first time that a country had come from another continent not to take something away, but to help Africans to achieve their freedom.” (Another excellent account of Cuba’s African policy is Egyptian director Jihan el Tahri’s film Cuba: An African Odyssey.)

Ultimately, Cuba’s successful battle against South Africa in Angola also hastened the Apartheid regime’s withdrawal from Namibia after 70 years of occupation, and that country’s subsequent independence.

In a 1998 speech, Fidel Castro told the South African Parliament (it was his first visit to the country) that by the end of the Cold War at least 381,432 Cuban soldiers and officers had been on duty or “fought hand-in-hand with African soldiers and officers in this continent for national independence or against foreign aggression.” Many Cubans also lost their lives in these wars.

Given this history, it was no surprise that one of Mandela’s first trips outside South Africa – after he was freed – was to Havana. There, in July 1991, Mandela, referred to Castro as “a source of inspiration to all freedom-loving people,” adding that Cuba, under Castro’s leadership “helped us in training our people, gave us resources to keep current with our struggle, trained our people as doctors.” At the end of his Cuban trip, Mandela responded to American criticism about his loyalty to Castro and Cuba: “We are now being advised about Cuba by people who have supported the Apartheid regime these last 40 years. No honorable man or woman could ever accept advice from people who never cared for us at the most difficult times.”

That loyalty to Cuba led to Mandela being boycotted by Cuban exiles on a 1990 visit to Miami, Florida. The local African-American community, however, supported Mandela’s stance.

The Cold War ended a long time ago, but Cuba continues its involvement on the African continent, including training Africans in Cuban universities. During the Ebola outbreak in three West African countries, even Cuba’s American critics had to acknowledge the Cuban contribution to alleviating the crisis. The Washington Post, a newspaper hardly favorable to Cuba’s government, conceded that Cuba’s “official response to Ebola seems far more robust than many countries far wealthier than it.” The Post noted – via Reuters – that Cuba had around 50,000 health workers working in 66 countries, including more than 4,000 in 32 African countries.

At one point during the Ebola crisis, Cuba – a country with only 11 million people – had supplied the largest contingent of foreign medical personnel by any single nation working alongside African medics.

Altogether fitting was Cuban President Raul Castro’s address at Nelson Mandela’s funeral in 2013. In Johannesburg, Raul reminded his audience: “We shall never forget Mandela’s moving homage to our common struggle when on the occasion of his visit to our country on July 26, 1991, he said, and I quote, ‘the Cuban people have a special place in the hearts of the peoples of Africa’.”

If Raul Castro decided to give all the credit for that love to his older brother Fidel, well, no one would blame him.

November 25, 2016

The Nigerians are coming

Ramsey Nouah in director Izu Ijukwu’s historical drama ’76 (2016). Credit: Still from the film.

Ramsey Nouah in director Izu Ijukwu’s historical drama ’76 (2016). Credit: Still from the film.The prominence of Nigerian film on the 2016 film festival circuit represents something of a sea change. Long withheld even from Pan-African film festivals and institutions, Nigerian cinema is finally being embraced on the international stage for its sheer diversity and capacity to adapt to dramatic technological and infrastructural shifts. The dam broke when in 2013, the Pan-African Film and Television Festival of Ouagadougou (FESPACO) finally abolished its controversial “no-video” policy, which had long excluded Nollywood films shot and distributed on VHS, VCD, and DVD. More recently, with the rise of the so-called New Nollywood, video formats have been supplemented with a capital-intensive return to celluloid film (both 16mm and 35mm) as a technology of production, distribution, and (in rare instances) exhibition.

Boasting a “Spotlight on Nigerian Cinema,” the 24th annual African Diaspora International Film Festival (ADIFF), which runs from tonight to December 11th in New York City, features the U.S. premieres of four Nigerian films—all of which were recently presented at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) as part of its Lagos-themed “City to City” program.

Shot on 16mm by the great cinematographer Yinka Edward, Izu Ijukwu’s historical drama ’76 (2016) is set against the backdrop of the abortive coup that led to the assassination of General Murtala Mohammed, Nigeria’s head of state for just six months in 1975 and 1976. In an Army barracks in Ibadan, Captain Joseph Dewa (Ramsey Nouah) lives with his pregnant wife Suzie (Rita Dominic). Their interethnic marriage (Joseph is from Nigeria’s Middle Belt, while the Igbo Suzie is from the southeast) is repeatedly tested by Suzie’s father, a veteran of Nigeria’s civil war, and by her brother, a self-serving bigot who derisively refers to non-Igbo ethnic groups as “those people.” The theme of tribalism places ’76 in a venerable Nollywood tradition, and Ijukwu, whose 2004 film Across the Niger depicts the Biafran War, is attuned to the historically specific dimensions of ethnic prejudice.

Set just 6 years after the defeat of the Biafrans, ’76 explores some of the civil war’s cultural and political reverberations, as when Suzie’s father, who has vivid memories of wartime atrocities committed against the Igbos, confronts her about Joseph’s ambiguous past and possible role in the conflict. Mostly, though, he falls back upon an ethnic-nationalist aversion to anyone who isn’t Igbo, as he defiantly informs his daughter, who replies, in Igbo, “Love has no boundaries.” As Suzie, Nollywood star Rita Dominic gives what may be her greatest performance to date in a role that, in quintessential Nollywood fashion, requires her to juggle multiple languages. Her costar, Ramsey Nouah, plays a man who, against his will, gets swept up in the attempted coup, as its architects privately engage in debates about inflation and denounce Mohammed for “abandoning our traditions and ideology” and appearing to serve Communist interests.

As a period piece, ’76 is a thrilling success. Edward’s 16mm cinematography cannily evokes an earlier era of image making—elegantly grainy and muted, with the look of old color photographs. (The celluloid factor represented a welcome change for Ijukwu, who, in order to approximate the look of 1960s documentary, had to digitally add grain to his film Across the Niger.) Shot on location at the Mokola Barracks in Ibadan and on Bar Beach in Lagos, ’76 is full of impressive, period-specific details best appreciated on a big screen: an array of Afro wigs, bell-bottom pants, and platform shoes; historically accurate military attire; vintage bottles of Star lager; and sporadic evidence of Nigeria’s oil boom, including a palatial movie house where Joseph and Suzie enjoy a raucous Indian comedy. In addition, Ijukwu incorporates archival footage of the coup and its aftermath, along with snippets of actual radio broadcasts, which contribute to the film’s docudramatic power. And then there’s the music: Bongos Ikwue, Nelly Uchendu, Fela Kuti, Prince Nico Mbarga and the Rocafils, and Miriam Makeba provide the intoxicating sounds of the 60s and 70s.

The three other Nigerian films in ADIFF’s lineup are set in the present. Steve Gukas’s 93 Days (2016), starring Bimbo Akintola, Keppy Ekpenyong-Bassey, and Danny Glover, tackles West Africa’s Ebola crisis, dramatizing the medical response to a diplomat (played by Ekpenyong-Bassey) who brings the virus to Nigeria after becoming infected in Liberia. Elegantly shot by the prolific Yinka Edward, and featuring dazzling images of Lagos, 93 Days is among the best Nigerian films to seriously consider the local effects of Ebola, and it is the first to dramatize the extensive (and ultimately successful) efforts to contain the virus in the country.

Part of a growing trend in Nigerian cinema, Niyi Akinmolayan’s The Arbitration (2016) is set in the high-stakes world of tech companies, where the worst imaginable fate is to cede a modicum of corporate control to an ambitious rival (while remaining a multimillionaire, of course). Adesua Etomi plays Dara, an up-and-coming tech professional who accuses her boss, Gbenga (played by O.C. Ukeje), of rape. That Dara was involved in an often-volatile affair with the married Gbenga complicates her case, as she quickly discovers, bitterly observing, “Apparently, the mistress of a married man can’t be raped.” The question of consent is soon eclipsed by financial considerations, however, as the eponymous mediation comes to focus on ownership and management of the 115-million-dollar company of which Gbenga is the CEO.

Rounding out ADIFF’s program of Nigerian films is Daniel Oriahi’s remarkable Taxi Driver (Oko Ashewo, 2015), an urban comedy that is at once uproariously funny, unsettlingly mysterious, and profoundly beautiful.

The setup is familiar: a village man moves to the big city (in this case, Lagos) in order to “make it.” The execution, however, is electrifying, as the hapless Adigun (a superb Femi Jacobs), derided as a naïve new arrival—a “Johnny Just Come”—must learn to navigate the streets of Lagos at nighttime, having inherited his late father’s taxicab (dubbed Tom Cruise). Guided by the swaggering Taiwo (Odunlade Adekola), Adigun encounters a range of memorable characters—some comical, others threatening—in Oriahi’s exuberant tribute to Lagos Island.

November 22, 2016

Don’t call me Toubab

Author in front of Kanifing Estate, Gambia via Instagram.

Author in front of Kanifing Estate, Gambia via Instagram.It is mid-September. I am walking alone in the streets of Old Jeswang, a small neighborhood in Banjul, the capital of The Gambia, where I have been working as a health promotion intern for two weeks. I am wearing an H&M black and white stripped dress, an African print head wrap and pendant earrings.

“Toubab, Toubab, Toubab!” White person. People passing by shout, smiling and waving at me.

I am black. I am African. I am Rwandan. I look around. But there is no one but me. I stop. Partially shocked, partially amused. I wave and smile back. I think to myself, they are just kids. They don’t know. I walk.

Two weeks later, I head to Mustapha’s shop to get chicken and onions for the Yassa Gannarr I am about to cook for the first time. The Mauritanian shop keeper greets me. Amused and as if to provoke me, he calls me “Toubab”.

Not again, I think.

“Duma Toubab!” I am not a Toubab, I reply smiling, to hide what’s boiling inside of me.

As a Rwandan diasporan living in Montreal, my coming to The Gambia means a lot of things. Not just a break from Canada, but my first trip back to the continent after forcibly leaving Rwanda behind in 1994. It means experiencing what I always thought of “home,” but away from Rwanda.

Like many other Africans living in the diaspora and traveling to the continent for the first time, my trip to The Gambia symbolizes a long-awaited return: familiarity, comfort and kinship that is somewhat hard to find in places where we are constantly othered. For the first time, I am not a visible minority. Back in Canada, my blackness goes unquestioned. I am dark. My hair defies gravity.

My trip also means that I can see and experience The Gambia without Eurocentric lenses; on my own terms, not defined by some anthropological jargon-filled book. I am well aware of the many privileges I wear. As an African studies major however, I have grown critical of both overly pessimist and romanticized misrepresentations of Africa as an academic subject.

How dare do they call me Toubab? I am not here for it. I can’t bear to be othered.

I am not one to preach the romanticized unification of Africans or black people as “one people,” or fervently defend nationalism and patriotism. I know I am “other”. I am Rwandan and raised in Canada. But somewhere deep down, I wish they recognized a little bit of themselves in me. It is their association of me with whiteness or the West that I can’t take.

When I ask my Gambian friends about the meaning of the term, especially targeted at me, they reply that it is custom to refer to visibly white people and foreigners raised in the West as Toubabs. For them, it is more my lifestyle and habits that define me as a Toubab than my mentality. I am the typical “western lazy student”. I don’t wake up at 6am on weekends to clean my house or cook for the day. However, I adapt fairly easily, eat all local meals with no refrain, and hang out mostly with locals unlike my fellow western friends. Locals call Indians, Lebanese or Chinese people by their respective nationalities regardless of their western upbringing, so why not me?

I reflect a lot on authenticity. What does it mean to be truly “African”? More so, to be a “real African” woman? I surely do not meet the local criteria. Non-African foreigners aren’t expected to enact “authentic Africanness,” but I am, because of my heritage. I have failed at the test and thus, I am Toubab. Some won’t even acknowledge my Rwandan background, because I have never seen Rwanda. To them, I am Canadian. Period.

I surely was raised in Canada, but having spent most of my teenage and adult years fighting against skewed beauty standards, ideas of modernity and superiority rooted in white supremacy, I just couldn’t accept it. Even so, because for many, it meant that I was rich, that North America was better than The Gambia. Sure, our living conditions are different, but it is those romanticized ideas of the West that hurt the most.

I do not blame them, though. I realize how much we as diasporans, have a duty to bridge the gap. No more faking that we “made it.” No more romanticized African immigrant tales. As much as I am privileged, being called Toubab also signifies the erasure of my blackness and what it means to be black in white spaces. It signifies the erasure of my upbringing in the West as a Rwandan child, by Rwanda parents, who tried their best to inculcate in me the traditions, culture, history and language of our homeland while navigating exclusion, discrimination and feelings of not belonging.

Taiye Selasi, in her TED Talk (“Don’t ask where I’m from, ask where I’m a local”) proposed that home is where one grew up, lived or worked. As a “multi-local,” she (with British and American passports and living in Rome) rejects the concept of “coming from one country” as countries are merely concepts, their boundaries often unfixed, artificial. But what if my hometown, the country I grew up in hasn’t embraced me as local yet? Where am I local? What if I find solace in the resilience, the culture, the traditions of a land I have never seen?

As a diasporan, the constant quest for authenticity and belonging is one I grapple with on a daily basis. Longing for a land I have never seen. Not being western/White enough. Not being African/Rwandan enough. Processes of identity-making are complex. Ultimately, the hurt is rooted in constant feelings of not belonging. However, I now find solace in knowing that my acceptance is mine alone.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers