Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 293

December 19, 2016

Africa is a funds-raiser

Image via Playboy.

Image via Playboy.With all the excitement around us joining Jacobin, we were a bit worried that the fundraising part might have gotten a lost in the shuffle.

So with that we just wanted to make a reminder post for you to donate to Africa Is a Country! It will help us with our relaunch effort on the new platform covering operational costs, including paying up and coming African writers, photographers, and video makers, as well as expanding towards a print issue.

Africa Is a Country still a truly independent media platform that has largely been volunteer run. Over the years we’ve made a lot of effort to keep the site free from ad driven content, and corporate sponsors. That can only continue with help from our dear readers!

So please take some time to donate. You can do it by visiting this link: paypal.me/africasacountry — or by sending a check to: Jacobin Foundation, 388 Atlantic Avenue, Brooklyn NY 11217 (including “Africa Is a Country” in the memo line if mailing in your contribution).

Small donations can make a big impact! If you can only donate $5, $10, or $15 we would be grateful. Even more helpful would be to also share your favorite Africa is a Country article with a friend, and ask them to donate to support independent media!

To sweeten the incentive to contribute, we’ve also reopened our T-shirt shop. So if you haven’t gotten your’s yet, from now until the end of the year you can head there to grab your Africa Is a Country logo T’s!

The best books of 2016

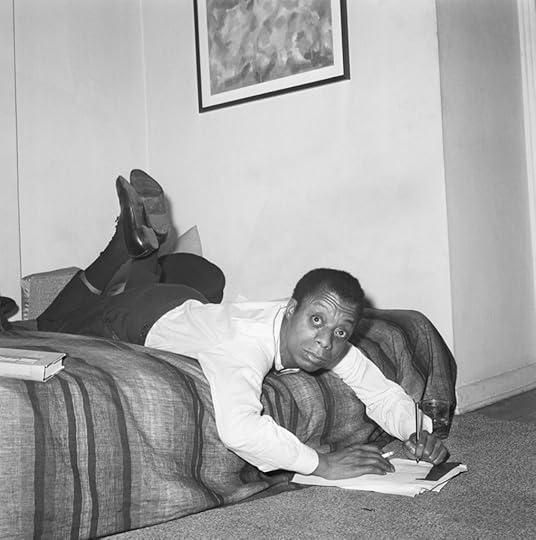

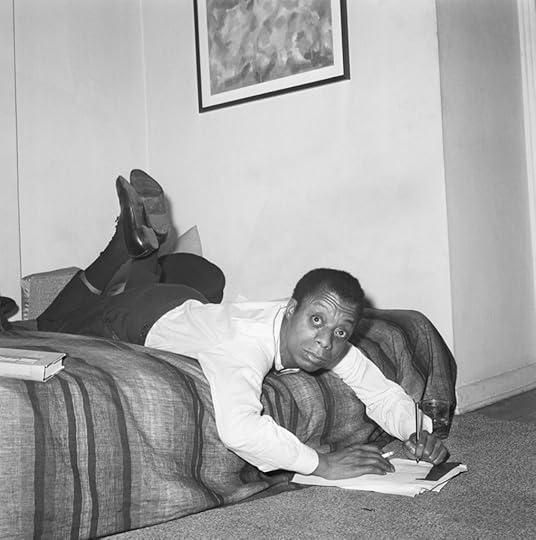

James Baldwin Gets Comfortable to Write. Image Credit Bettmann (CORBIS).

James Baldwin Gets Comfortable to Write. Image Credit Bettmann (CORBIS).We’re a bookish bunch at AIAC, and once a year we like to share some of our favorite reads from the year just gone. It always feels like there’s too much to read, because there is. But one can always read more! So here’s some more to add to your reading pile for 2017.

Wangui Kimari

City of Thorns: Nine Lives in the World’s Largest Refugee Camp by Ben Rawlence (Picador, 2016): I was bracing myself for another Michela Wrong type narrative – Africans deep in the abyss of every kind of darky maelstrom. But the intricate and vibrant portraits painted here of Dadaab’s people making life amidst the violent encampments of Kenya’s self-interest, humanitarian inconsistency, Al-Shabaab, and the many structural and intimate manifestations of this, are very moving.

Chika Unigwe

Born on a Tuesday by Elnathan John (Grove Press, 2016): relevant, insightful, timely and beautiful prose. Dantala, John’s protagonist, is a compelling character who stays with you long after you’ve turned the last page.

Zachary Levenson

Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi (Penguin/Random House New York, 2016). When a friend recommended this historical novel about the Gold Coast slave trade, I was skeptical: Gyasi is younger than I am, and how many historical novels have been written about slavery? Wrong. This book is phenomenal from start to finish. A progression of short stories about characters from two family lines in Ghana, Gyasi’s book demonstrates how the intimate life of the slave trade transforms understandings of race, power, and social structure in both Ghana and the US. For a book that only treats each of its characters briefly, the degree of character development is remarkable.

Gabeba Baderoon

Pumla Dineo Gqola’s Rape: A South African Nightmare (Jacana, 2015) shows how the extraordinary scale of sexual violence in South Africa became ordinary and invisible. The grave reality has begun to change, with students in the fees movements refusing to accept that sexual violence is a necessary price of struggle.

Neelika Jayawardane

Mr. Loverman, by Bernardine Evaristo (Penguin, 2013). Barrington “Barry” Walker, a Caribbean transplant to Stoke Newington, has been playing the field on the Down Low all his adult sexual life. At 74, he is still not ready to come out because…well, his wife, Carmel, is a fine cook (I mean, what man could reproduce her fried plantains or her stews?!). And he likes his house, and the social role he plays in his community as a three-piece suit wearing dapper gent with “a certain je ne sais whatsit” who built a not-inconsiderable real-estate business. It’s the “What would people say” about him being a “Buggerer of men” and the fear of resulting social death that stops him from being out in the open about his life-long love – whom he followed, from Antigua, all the way to Great Britain – the long-suffering Morris de la Roux. Although the novel revolves around Barry and Morris, and the “will they or won’t they” question, part of the fun of reading this book is in that Evaristo is grounded in post-colonial criticism. She does not reduce Carmel’s character to a devout Christian who may be using her hellfire and brimstone church morality to mask her own loneliness. We get to question Carmel’s own reasons for wanting to immigrate to Britain, though she came from a wealthy, landowning Antiguan family. In her youthful projections of escape, romantic love and desire for freedom from an abusive father are conflated with images of an idealized, pastoral England (even though Evaristo is careful to note that the actual Antiguan scenery around her is luscious – there’s even a hummingbird buzzing around as she dreams of the glories dear old England will offer). We see how Britain has carefully constructed and projected itself as the place in which ideal love, beauty, and fulfillment exists – through everything from images on teacups, popular narratives and the novels that Carmel reads. Needless to say, when she gets to London with Barry, she finds neither romantic love nor self-actualization. Even her skin looks like shit (happily restored, however, when she returns to Antigua). Through Carmel’s disappointing journey, we re-evaluate our own romance with the vestigial remnants of the British Empire.

Adam Shatz

This year I immersed myself in the work of two extraordinary French-language writers; both are just beginning to translated into English, and both help, in very different ways, to explain the current political impasse, particularly around the question of identity.

Zahia Rahmani is a Paris-based art historian and curator who is also an essayist and novelist. Born in 1962 in Algeria, the year the country won its independence from France, she moved to the French countryside with her family only a few years later, because her father was accused of being aharki, a member of the Algerian forces who fought alongside the French. (Although jailed for several years, he was comparatively lucky; tens of thousands of harkis were killed after the war, many in grisly public executions.) Rahmani, who grew up in a village where she and her Kabyle Berber family were the only Muslims, has written of this experience in three autobiographical fictions, one of which, France, Story of a Childhood, has just been translated by Yale University Press. The novel is a fragmentary, intensely lyrical and deeply affecting portrait of the artist as a young “Muslim” girl, reckoning with her place in an ostensibly inclusive yet hostile republic. In France, identity is a puzzle and a project, not a simple question of embracing some fixed “self.” In fact, the book that saves her is not a work of French or Algerian literature, but Richard Wright’s Black Boy, a reminder of the power of language to forge connections beyond identity.

Enzo Traverso is a historian, not a novelist, but he addresses a set of related questions in The End of Jewish Modernity, newly translated by Pluto Press. Born and raised in Italy, Traverso, who teaches in Paris and writes in French, has become one of our most trenchant guides to Europe’s descent into barbarism in the 1930s and 40s: in other words, to our present. The End of Jewish Modernity explores the rise and fall of the dissident Jewish intellectual tradition (from Marx and Rosa Luxembourg to Walter Benjamin and Hannah Arendt) that powerfully shaped Western critical thought. As Traverso explains in this terse, erudite and elegiac volume, radical Jewish modernity went into decline with the Nazi genocide, the creation of Israel (on the ruins of Arab Palestine), and the incorporation of Jews, the West’s historic Other, into the establishment. Yet its analyses of alienation, statelessness, racism and mass culture have seldom felt more prescient, as Traverso shows in Blood and Fire, a powerful and disturbing study of Europe’s “civil war” from 1914-45, newly translated by Verso.

Gina Ulysse

In Little Edges (Wesleyan University, 2015) Fred Moten uses white spaces on the page to lure and guide us through vastness, and the rhythmic poetics of his “shaped prose.” His crafted, homages to dailies, the greats are evidence of the avant-garde marronage in jazz – a reminder that poetry is necessary in these times to breathe. (I re-read it twice this year).

Tseliso Monaheng

Bongani Madondo is class, style and sophistication. These traits he carries through and lets bleed through his writing. The results are what we have here, in 2016. Around May this year, Pan-Macmillan SA released another tome from the gahd himself. Titled Sigh, the Beloved Country — a subversion of the ole Alan Paton’s book title – the scholarly treatise follows on from I’m Not Your Weekend Special (2014), the collection of essays on Brenda Fassie, in which he was both contributor and editor. This time, Brother B levitates atop kush-cautioned keys, reaching a high whose viewfinder caters for recollections of train rides to and from Hammanskraal into Pretoria during the bum years of Apartheid, to rappers, their drug habits, and what the consequences of their actions say about this project-in-progress that we term democracy. It’s the gift that keeps overflowing; essential reading for now and beyond. Cop it!

Jill Kelly

Favorite read this year is The Underground (Restless Books, 2013). Uzbek novelist Hamid Ismailov follows the lonely child of a Siberian woman and an African athlete in Moscow for the 1980s Olympics through the city and its metro. Chapters named after metro stations explore what it might have meant to be black and Russian in the Soviet Union’s last decade and its aftermath. Reading Africa from Dallas, I’d be remiss not to recommend (newly translated with Deep Vellum Press) Fouad Laroui’s short story collection The Curious Case of Dassoukine’s Trousers (Deep Vellum Publishing, 2016) for deep laughs and Ananda Devi’s brutal Eve Out of Her Ruins (Deep Vellum Publishing, 2016)for Mauritius beyond the resorts and beaches.

Herman Wasserman

One of the books I enjoyed this year was Richard Poplak and Kevin Bloom’s Continental Shift (Portobello Books, 2016). I reviewed it length in AIAC, but here is an extract again:

Continental Shift is an entertaining and stimulating recounting of the authors’ experience of traveling thousands of kilometers and wading through academic books, historical documents, policy documents and news articles. It covers a broad range of topics – construction in Namibia, the building of a dam in Botswana, mining in Zimbabwe, Nollywood in Nigeria, food security in Ethiopia, realpolitik in South Sudan and conflict in Central African Republic. Continental Shift’s biggest achievement is its lively, and sometimes even humorous tone. It’s a heady mix of memoir, ethnography, analysis, travel writing and at times comes close to a type of political poetry. The accessibility and lucidity of this ambitious project is largely thanks to the distinctive style of writing – fans of Poplak’s political journalism in the Daily Maverick will be familiar with his destructive sense of irony. But this is also a gripping tale because of its reliance on first-hand experiences and field work, several conversations and interviews, and sharp observations on the ground.

Jon Soske

Jack Shenker’s The Egyptians: A Radical History of Egypt’s Unfished Revolution (The New Press, 2016). A great writer, Shenker’s account of the Egyptian revolution and its betrayal is perceptive, nuanced and hard-hitting. It’s a welcome break from the revolutionary tourism that has so often passed as left analysis of the Arab revolts. Shenker understands the everyday struggles of Egyptians as the cutting edge of the global struggle to extend democracy from electoral systems to every aspect of our lives. Also, Keeanga-Yammata Taylor’s brilliant and stirring From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation (Haymarket, 2016) provides a synoptic historical account of U.S. White supremacy, counter insurgency, and the betrayals of the black elite. It’s hard-headed in its diagnosis of the obstacles confronting anti-racist and radical politics while insisting on the new possibilities of struggle illuminated by Black Lives Matter. Finally, I would whole heartedly recommend Nnedi Okorador’s beautiful work of magical futurism, The Book of Phoenix (Hodder, 2016). And everything else she has written.

Aditi Surie von Czechowski

Darryl Pinckney’s Black Deutschland (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2016) is a masterpiece of adaptation and evasion. Set between Berlin and Chicago, it narrates the psychic aftermath of black resistance and the impossibility of choice. A meditation on blackness as politics and the promise of different futures that somehow never quite pan out in the face of structural racism, this book left me reeling.

Dan Magaziner

Best fiction: Jose Eduardo Agualusa, A General Theory of Oblivion (Harvill Secker, 2015). The revolution comes to Luanda, most Portuguese flee, Ludo is left behind and resolves never to go outside again. Historical and urban transformations are glimpsed only in moments. Artfully wrought, melancholic, moving and hilarious. And published in English by a small independent press to boot!

Best academic: Neil Roberts, Freedom as Maroonage (University of Chicago Press, 2015). The necessary relationship between struggle and freedom, reflecting on the efforts of slaves to establish durable communities through flight. Powerfully written, theoretically rigorous and good to think with in depressing times.

Thando Njovane

Yvonne Adhiambo Owour’s Dust (2014). Dust is a novel mired as much in grief and loss as it is in love (both filial and romantic) and redemption. It is an epic with acute insights into the human spirit and psychological motivations, rooted in the land’s memory of itself and its people, and covered in dust. Immaculately crafted and beautifully lyrical, Dust endures as a love letter to Kenya and to us all. I can only recommend Dust. I’m haunted by it.

Sophia Azeb

Stuart Hall, The Hard Road to Renewal: Thatcherism and the Crisis of the Left (Verso, 1988). On Wednesday, November 9, I dragged myself out of bed and made way to my office. There, just around the corner from Washington Square Park and only a few hours after the first of the spontaneous protests against the U.S. election results, I re-read Ruth Wilson Gilmore’s 2010 Presidential Address to the American Studies Association, “What Is To Be Done?” (answer: “Organise!”), and the late Stuart Hall’s only single-authored monograph: The Hard Road to Renewal: Thatcherism and the Crisis of the Left. Published in1988 and drawn from an array of his previously published articles on the topic, Hall theorizes that the concept of Thatcherism is based on the state and public investment in “free market, strong state, iron times, and authoritarian populism” and laments that Thatcherism is enabled, if not encouraged, by the dilution of the left. In one particularly damning essay, Hall writes: “If Labour has no other function, its role is surely to generalize the issues of the class it claims to represent. Instead its main aim was damage limitation.” Sound familiar?

Despite this cheerless assessment, Stuart Hall’s valuable insights (doubtless the inspiration for a new series of texts by and about Hall from Duke University Press in 2017) are found in the realm of possibility that understanding and articulating Thatcherism as a phenomenon provides: if we understand how Thatcherism successfully modernized regressive, anti-worker politics, perhaps the left can embrace our own radical politics (in Hall’s writing, the example of feminism is given. For our times, we might look to Black Lives Matter and the Water Protectors at Oceti Sakowin camp) to the same end.

Abdi Latif Ega

Okey Ndibe’s Arrows of Rain (Heinemann, 2000) is a powerful, nuanced and highly evocative exploration of the nexus between silence and power (my favorite character in the novel, an elderly woman, entreats her grandson, “A story that must be told never forgives silence.”). It is at once an enthralling, fast-paced narrative and a sardonic meditation on the ethical, political and social dimensions of silence and the imperative to bear witness.

Ndibe’s second novel, Foreign Gods, Inc. (Soho Press, 2014) offers a fresh, sharp-witted perspective on the modernist impulse to turn everything, including (in the case of the novel, deities and sacred objects) into commodities. Ndibe’s latest, a memoir titled Never Look an American in the Eye: Flying Turtles, Colonial Ghosts, and the Making of a Nigerian American (Soho Press, 2016), offers memorable and instructive vignettes from the author’s life as an immigrant in the United States. A wonderfully humorous writer, Ndibe uses the memoir to illuminate essential truths about the hard, sometimes even harrowing, price that many immigrants must pay for their rite of passage.

Okey Ndibe’s writing, especially his first two novels, have received enthusiastic reviews and been praised by such literary greats as Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Wole Soyinka, and African-American writer, John Edgar Wideman.

Elliot Ross

For whatever reason, this was the year I couldn’t stop reading memoirs, having previously been somewhat circumspect about the genre. All excellent in different ways were: Emily Witt’s Future Sex (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2016), Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts (Graywolf Press, 2015), Samuel Delany’s The Motion of Light in Water (Arbor House, 1988), Elizabeth Alexander’s The Light of the World (Grand Central Publishing, 2015), and Aleksandar Hemon’s The Book of My Lives (Macmillan, 2014). Highly recommended.

Africa is a Country Recommends… (our 2016 book list).

James Baldwin Gets Comfortable to Write. Image Credit Bettmann (CORBIS).

James Baldwin Gets Comfortable to Write. Image Credit Bettmann (CORBIS).*Africa is a Country is currently fundraising for a website relaunch as part of the Jacobin Family of publications. Head here to read up on the transition and to donate!

We’re a bookish bunch at AIAC, and once a year we like to share some of our favorite reads from the year just gone. It always feels like there’s too much to read, because there is. But one can always read more! So here’s some more to add to your reading pile for 2017.

Wangui Kimari

City of Thorns: Nine Lives in the World’s Largest Refugee Camp by Ben Rawlence (Picador, 2016): I was bracing myself for another Michela Wrong type narrative – Africans deep in the abyss of every kind of darky maelstrom. But the intricate and vibrant portraits painted here of Dadaab’s people making life amidst the violent encampments of Kenya’s self-interest, humanitarian inconsistency, Al-Shabaab, and the many structural and intimate manifestations of this, are very moving.

Chika Unigwe

Born on a Tuesday by Elnathan John (Grove Press, 2016): relevant, insightful, timely and beautiful prose. Dantala, John’s protagonist, is a compelling character who stays with you long after you’ve turned the last page.

Zachary Levenson

Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi (Penguin/Random House New York, 2016). When a friend recommended this historical novel about the Gold Coast slave trade, I was skeptical: Gyasi is younger than I am, and how many historical novels have been written about slavery? Wrong. This book is phenomenal from start to finish. A progression of short stories about characters from two family lines in Ghana, Gyasi’s book demonstrates how the intimate life of the slave trade transforms understandings of race, power, and social structure in both Ghana and the US. For a book that only treats each of its characters briefly, the degree of character development is remarkable.

Gabeba Baderoon

Pumla Dineo Gqola’s Rape: A South African Nightmare (Jacana, 2015) shows how the extraordinary scale of sexual violence in South Africa became ordinary and invisible. The grave reality has begun to change, with students in the fees movements refusing to accept that sexual violence is a necessary price of struggle.

Neelika Jayawardane

Mr. Loverman, by Bernardine Evaristo (Penguin, 2013). Barrington “Barry” Walker, a Caribbean transplant to Stoke Newington, has been playing the field on the Down Low all his adult sexual life. At 74, he is still not ready to come out because…well, his wife, Carmel, is a fine cook (I mean, what man could reproduce her fried plantains or her stews?!). And he likes his house, and the social role he plays in his community as a three-piece suit wearing dapper gent with “a certain je ne sais whatsit” who built a not-inconsiderable real-estate business. It’s the “What would people say” about him being a “Buggerer of men” and the fear of resulting social death that stops him from being out in the open about his life-long love – whom he followed, from Antigua, all the way to Great Britain – the long-suffering Morris de la Roux. Although the novel revolves around Barry and Morris, and the “will they or won’t they” question, part of the fun of reading this book is in that Evaristo is grounded in post-colonial criticism. She does not reduce Carmel’s character to a devout Christian who may be using her hellfire and brimstone church morality to mask her own loneliness. We get to question Carmel’s own reasons for wanting to immigrate to Britain, though she came from a wealthy, landowning Antiguan family. In her youthful projections of escape, romantic love and desire for freedom from an abusive father are conflated with images of an idealized, pastoral England (even though Evaristo is careful to note that the actual Antiguan scenery around her is luscious – there’s even a hummingbird buzzing around as she dreams of the glories dear old England will offer). We see how Britain has carefully constructed and projected itself as the place in which ideal love, beauty, and fulfillment exists – through everything from images on teacups, popular narratives and the novels that Carmel reads. Needless to say, when she gets to London with Barry, she finds neither romantic love nor self-actualization. Even her skin looks like shit (happily restored, however, when she returns to Antigua). Through Carmel’s disappointing journey, we re-evaluate our own romance with the vestigial remnants of the British Empire.

Adam Shatz

This year I immersed myself in the work of two extraordinary French-language writers; both are just beginning to translated into English, and both help, in very different ways, to explain the current political impasse, particularly around the question of identity.

Zahia Rahmani is a Paris-based art historian and curator who is also an essayist and novelist. Born in 1962 in Algeria, the year the country won its independence from France, she moved to the French countryside with her family only a few years later, because her father was accused of being aharki, a member of the Algerian forces who fought alongside the French. (Although jailed for several years, he was comparatively lucky; tens of thousands of harkis were killed after the war, many in grisly public executions.) Rahmani, who grew up in a village where she and her Kabyle Berber family were the only Muslims, has written of this experience in three autobiographical fictions, one of which, France, Story of a Childhood, has just been translated by Yale University Press. The novel is a fragmentary, intensely lyrical and deeply affecting portrait of the artist as a young “Muslim” girl, reckoning with her place in an ostensibly inclusive yet hostile republic. In France, identity is a puzzle and a project, not a simple question of embracing some fixed “self.” In fact, the book that saves her is not a work of French or Algerian literature, but Richard Wright’s Black Boy, a reminder of the power of language to forge connections beyond identity.

Enzo Traverso is a historian, not a novelist, but he addresses a set of related questions in The End of Jewish Modernity, newly translated by Pluto Press. Born and raised in Italy, Traverso, who teaches in Paris and writes in French, has become one of our most trenchant guides to Europe’s descent into barbarism in the 1930s and 40s: in other words, to our present. The End of Jewish Modernity explores the rise and fall of the dissident Jewish intellectual tradition (from Marx and Rosa Luxembourg to Walter Benjamin and Hannah Arendt) that powerfully shaped Western critical thought. As Traverso explains in this terse, erudite and elegiac volume, radical Jewish modernity went into decline with the Nazi genocide, the creation of Israel (on the ruins of Arab Palestine), and the incorporation of Jews, the West’s historic Other, into the establishment. Yet its analyses of alienation, statelessness, racism and mass culture have seldom felt more prescient, as Traverso shows in Blood and Fire, a powerful and disturbing study of Europe’s “civil war” from 1914-45, newly translated by Verso.

Gina Ulysse

In Little Edges (Wesleyan University, 2015) Fred Moten uses white spaces on the page to lure and guide us through vastness, and the rhythmic poetics of his “shaped prose.” His crafted, homages to dailies, the greats are evidence of the avant-garde marronage in jazz – a reminder that poetry is necessary in these times to breathe. (I re-read it twice this year).

Tseliso Monaheng

Bongani Madondo is class, style and sophistication. These traits he carries through and lets bleed through his writing. The results are what we have here, in 2016. Around May this year, Pan-Macmillan SA released another tome from the gahd himself. Titled Sigh, the Beloved Country — a subversion of the ole Alan Paton’s book title – the scholarly treatise follows on from I’m Not Your Weekend Special (2014), the collection of essays on Brenda Fassie, in which he was both contributor and editor. This time, Brother B levitates atop kush-cautioned keys, reaching a high whose viewfinder caters for recollections of train rides to and from Hammanskraal into Pretoria during the bum years of Apartheid, to rappers, their drug habits, and what the consequences of their actions say about this project-in-progress that we term democracy. It’s the gift that keeps overflowing; essential reading for now and beyond. Cop it!

Jill Kelly

Favorite read this year is The Underground (Restless Books, 2013). Uzbek novelist Hamid Ismailov follows the lonely child of a Siberian woman and an African athlete in Moscow for the 1980s Olympics through the city and its metro. Chapters named after metro stations explore what it might have meant to be black and Russian in the Soviet Union’s last decade and its aftermath. Reading Africa from Dallas, I’d be remiss not to recommend (newly translated with Deep Vellum Press) Fouad Laroui’s short story collection The Curious Case of Dassoukine’s Trousers (Deep Vellum Publishing, 2016) for deep laughs and Ananda Devi’s brutal Eve Out of Her Ruins (Deep Vellum Publishing, 2016)for Mauritius beyond the resorts and beaches.

Herman Wasserman

One of the books I enjoyed this year was Richard Poplak and Kevin Bloom’s Continental Shift (Portobello Books, 2016). I reviewed it length in AIAC, but here is an extract again:

Continental Shift is an entertaining and stimulating recounting of the authors’ experience of traveling thousands of kilometers and wading through academic books, historical documents, policy documents and news articles. It covers a broad range of topics – construction in Namibia, the building of a dam in Botswana, mining in Zimbabwe, Nollywood in Nigeria, food security in Ethiopia, realpolitik in South Sudan and conflict in Central African Republic. Continental Shift’s biggest achievement is its lively, and sometimes even humorous tone. It’s a heady mix of memoir, ethnography, analysis, travel writing and at times comes close to a type of political poetry. The accessibility and lucidity of this ambitious project is largely thanks to the distinctive style of writing – fans of Poplak’s political journalism in the Daily Maverick will be familiar with his destructive sense of irony. But this is also a gripping tale because of its reliance on first-hand experiences and field work, several conversations and interviews, and sharp observations on the ground.

Jon Soske

Jack Shenker’s The Egyptians: A Radical History of Egypt’s Unfished Revolution (The New Press, 2016). A great writer, Shenker’s account of the Egyptian revolution and its betrayal is perceptive, nuanced and hard-hitting. It’s a welcome break from the revolutionary tourism that has so often passed as left analysis of the Arab revolts. Shenker understands the everyday struggles of Egyptians as the cutting edge of the global struggle to extend democracy from electoral systems to every aspect of our lives. Also, Keeanga-Yammata Taylor’s brilliant and stirring From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation (Haymarket, 2016) provides a synoptic historical account of U.S. White supremacy, counter insurgency, and the betrayals of the black elite. It’s hard-headed in its diagnosis of the obstacles confronting anti-racist and radical politics while insisting on the new possibilities of struggle illuminated by Black Lives Matter. Finally, I would whole heartedly recommend Nnedi Okorador’s beautiful work of magical futurism, The Book of Phoenix (Hodder, 2016). And everything else she has written.

Aditi Surie von Czechowski

Darryl Pinckney’s Black Deutschland (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2016) is a masterpiece of adaptation and evasion. Set between Berlin and Chicago, it narrates the psychic aftermath of black resistance and the impossibility of choice. A meditation on blackness as politics and the promise of different futures that somehow never quite pan out in the face of structural racism, this book left me reeling.

Dan Magaziner

Best fiction: Jose Eduardo Agualusa, A General Theory of Oblivion (Harvill Secker, 2015). The revolution comes to Luanda, most Portuguese flee, Ludo is left behind and resolves never to go outside again. Historical and urban transformations are glimpsed only in moments. Artfully wrought, melancholic, moving and hilarious. And published in English by a small independent press to boot!

Best academic: Neil Roberts, Freedom as Maroonage (University of Chicago Press, 2015). The necessary relationship between struggle and freedom, reflecting on the efforts of slaves to establish durable communities through flight. Powerfully written, theoretically rigorous and good to think with in depressing times.

Thando Njovane

Yvonne Adhiambo Owour’s Dust (2014). Dust is a novel mired as much in grief and loss as it is in love (both filial and romantic) and redemption. It is an epic with acute insights into the human spirit and psychological motivations, rooted in the land’s memory of itself and its people, and covered in dust. Immaculately crafted and beautifully lyrical, Dust endures as a love letter to Kenya and to us all. I can only recommend Dust. I’m haunted by it.

Sophia Azeb

Stuart Hall, The Hard Road to Renewal: Thatcherism and the Crisis of the Left (Verso, 1988). On Wednesday, November 9, I dragged myself out of bed and made way to my office. There, just around the corner from Washington Square Park and only a few hours after the first of the spontaneous protests against the U.S. election results, I re-read Ruth Wilson Gilmore’s 2010 Presidential Address to the American Studies Association, “What Is To Be Done?” (answer: “Organise!”), and the late Stuart Hall’s only single-authored monograph: The Hard Road to Renewal: Thatcherism and the Crisis of the Left. Published in1988 and drawn from an array of his previously published articles on the topic, Hall theorizes that the concept of Thatcherism is based on the state and public investment in “free market, strong state, iron times, and authoritarian populism” and laments that Thatcherism is enabled, if not encouraged, by the dilution of the left. In one particularly damning essay, Hall writes: “If Labour has no other function, its role is surely to generalize the issues of the class it claims to represent. Instead its main aim was damage limitation.” Sound familiar?

Despite this cheerless assessment, Stuart Hall’s valuable insights (doubtless the inspiration for a new series of texts by and about Hall from Duke University Press in 2017) are found in the realm of possibility that understanding and articulating Thatcherism as a phenomenon provides: if we understand how Thatcherism successfully modernized regressive, anti-worker politics, perhaps the left can embrace our own radical politics (in Hall’s writing, the example of feminism is given. For our times, we might look to Black Lives Matter and the Water Protectors at Oceti Sakowin camp) to the same end.

Abdi Latif Ega

Okey Ndibe’s Arrows of Rain (Heinemann, 2000) is a powerful, nuanced and highly evocative exploration of the nexus between silence and power (my favorite character in the novel, an elderly woman, entreats her grandson, “A story that must be told never forgives silence.”). It is at once an enthralling, fast-paced narrative and a sardonic meditation on the ethical, political and social dimensions of silence and the imperative to bear witness.

Ndibe’s second novel, Foreign Gods, Inc. (Soho Press, 2014) offers a fresh, sharp-witted perspective on the modernist impulse to turn everything, including (in the case of the novel, deities and sacred objects) into commodities. Ndibe’s latest, a memoir titled Never Look an American in the Eye: Flying Turtles, Colonial Ghosts, and the Making of a Nigerian American (Soho Press, 2016), offers memorable and instructive vignettes from the author’s life as an immigrant in the United States. A wonderfully humorous writer, Ndibe uses the memoir to illuminate essential truths about the hard, sometimes even harrowing, price that many immigrants must pay for their rite of passage.

Okey Ndibe’s writing, especially his first two novels, have received enthusiastic reviews and been praised by such literary greats as Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Wole Soyinka, and African-American writer, John Edgar Wideman.

Elliot Ross

For whatever reason, this was the year I couldn’t stop reading memoirs, having previously been somewhat circumspect about the genre. All excellent in different ways were: Emily Witt’s Future Sex (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2016), Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts (Graywolf Press, 2015), Samuel Delany’s The Motion of Light in Water (Arbor House, 1988), Elizabeth Alexander’s The Light of the World (Grand Central Publishing, 2015), and Aleksandar Hemon’s The Book of My Lives (Macmillan, 2014). Highly recommended.

*Africa is a Country is currently fundraising for a website relaunch as part of the Jacobin Family of publications. Head here to read up on the transition and to donate!

December 17, 2016

Weekend Music Break No.101

It’s the last music break of the year, and we leave 2016 with the 101st edition. It’s been a pleasure for me to do these playlist. If you’ve been enjoying them as well, make sure to donate to our end of the year funds drive, so we can continue to expand our coverage of the global African pop culture map!

Weekend Music Break No.101

1) This edition we kick things off with Blitz the Ambassador who has a new album out this week. The above video, shot in Salvador de Bahia, Brazil, is the final installment of his self-directed Diasporadical video triology (we’ve featured part 1 and part 2 here before). Be sure to check out the album that perfectly accompanies this video short collection. 2) Next up, we head to Nigeria with Santi and Odunsi and their “Gangster Fear” video, shot in Lagos’ streets and teenage house parties. 3) After that we get some rhythmic fire from Cameroon’s Reniss, who teaches us about the joys of Cameroonian cooking. 4) We have a habit of posting Booba videos here on the Weekend Music Break, why break with tradition? Headed to DKR (and once again linking with Sidiki Diabate) to represent his Senegalese roots, Booba certainly shows he has no intention to. 5) UK Afrobeats og Silvastone teams up with Frank T Blucas in the video for “Remedy” showing a warmer side of London that is probably being missed by that city’s residents right now. 6) Teddy Yo and Joe Lox take us to Addis Ababa showing what might be the exciting growth of an indigenous Ethiopian Hip Hop scene? (Take back those samples brothers!) 7) A UK-raised Sierra Leonean, Brother Portrait reflects on the Black British experience in this video poem for “Seeview/Rearview”. 8) Next up Ghalileo attends a funeral in Ghana, and channels a history of pan-African leadership in the process. 9) Then, Vic Mensa takes on police brutality in Chicago. 10) And finally, Star Zee takes on “2 Much” corruption and general social malaise in Sierra Leone.

Have a great weekend and a very happy holiday season wherever you are, and whatever you believe!

December 12, 2016

Making Europe White… Again

French police officers citing a woman wearing a Burqini on a French beach. Image Credit: Bestimage via NYTimes.

French police officers citing a woman wearing a Burqini on a French beach. Image Credit: Bestimage via NYTimes.Zygmunt Bauman, the renowned Polish sociologist, calls them the emergent precariat. Shaken by the false promises of global neoliberal capitalism, the emergent precariat is a significant class of white Europeans living in constant fear of losing their positions of privilege. Their lives are characterized by a sense that they are in a constant state of crisis – the death of multiculturalism, the moral panic about terrorism, the collapse of the European Union and continued European economic paralysis. The global crisis of 2008, in particular, rapidly expanded and intensified their anxieties. Stalked by these, and material precarity, refugees and migrants have become the embodiment of their greatest fears – a change in a nation’s color and the real specter of economic meltdown in Europe.

Against this growing “influx” and increasing visibility of non-Europeans, right-wing populist politicians, aided by the moral panic induced by mainstream western media, appear to be urgently summoning the emergent precariat to defend their “ancestral lands” against threatening “hordes” of migrants. The words of former French president Nicolas Sarkozy to “bring back authority and defend the French Republic,” (to kick start a failed second presidential bid), are eerily similar to those as say President-elect Donald Trump’s to “make America great again,” and as geographically proximate as Geert Wilders of the Netherlands who summons the Dutch to make the “Netherlands Ours Again.” Indeed, much of this rhetoric is about the restoration of economic nationalism and a purported disdain for the nefarious political elites in Brussels and Washington.

But there is something more sinister at work. The true power of this ideological production is not dictated by what is really said but rather by what is omitted. Both in Europe and the United States, there is a nostalgia for when Europe and the U.S. were whiter – a supposed return to former glory and greatness – and an accompanying fear that particular migrants are rapidly diluting the whiteness of their countries. Central to this rhetoric, is a coded racial grammar directed largely at Arab and or Muslim and Black Africans. By using the phrases “ours” and “bring back,” while simultaneously omitting any references to race, they are tacitly signaling the idea that Europe excludes those historically categorized as non-European; those that are not white. In the case of America, making it “great again” is a direct reference to eight years of leadership under a black president, whose birthplace was relentlessly questioned by Trump.

These leaders are communicating that even if you are indeed here, you don’t really or fully belong. Your sojourn is temporary, you may even be “born in, but [are] not of [this] society” as critical theorist David Theo Goldberg reminds us. Sarkozy, in a speech to launch his re-entry into French politics indicated precisely : “Being French means having a language, a history, and a way of life in common.” And in specific reference to public contentions about the burqini (the bathing suit worn by many Muslim women): “People cannot say ‘I want to be French, but in my own way’.” Here we see rhetorical strategies that continue to support “national fantasies” and reinforce the characterization of migrant populations as deeply suspect and potentially disloyal; this manifest in their apparent unwillingness to integrate as prescribed by French authorities. Sarkozy went on to note: “Wearing a burqini is a radical, political gesture, a provocation… the women who are choosing to wear it are testing the resilience of the Republic.”

Crucially, this kind of rhetoric invokes violent cultural induction, internal boundary making and the expansion of illegality. Earlier this year, we saw French Muslim women interrogated by French police for wearing burqinis on the beach. In the pursuit of apparently sustaining secularism, French authorities remain steadfastly opposed to veiling, to the point of dramatically curtailing otherwise “benign liberties of self-expression”. In Germany, Frauke Petry, the leader of the AfD – Germany’s Far Right party – in April of this year demanded that headscarves be banned in schools and universities and minarets prohibited. Succumbing to this pressure, Chancellor Angela Merkel’s Interior Minister called for a partial ban on burkas in a range of public contexts, noting that it would apply in “places where it is necessary for our societies to coexistence.”

But what is really at play here? When asked by French broadcast media about the burqini, Marine Le Pen of the French National Front party said: “The burqini is a symptom. One of the multiple symptoms of the rise of fundamentalist Islam in France for many years… it is about demands that are designed to say ‘We Muslims, though not all are in agreement with this, we want to eat differently, we want to live differently, and we want to dress differently’.”

Differently from whom precisely? Therein lies the revealing point of departure for Le Pen. Women in burqinis – “consenting victims” as she calls them – represent an affront to whiteness, white aesthetic comforts and more generally mainstream western culture. It is this that Muslims want to be different from. And in western societies structured by racism, the state and the politically powerful engage in disciplining immigrant difference and mobility into “commensurable citizens and commodifiable cultures”; cultures which are innocuously referred to as “authentically” French or German.

Worryingly, these racist discourses serve to legitimate increasingly stringent immigration controls and mechanisms of refugee incorporation. In the current European migration policy regime, migrant’s integration is seen as precondition for achieving formal rights of residence and finally citizenship: formal tests for citizenship were practices in six countries in 1998 rising to nineteen by 2010. However, this testing – and other forms of control – are not only practiced at entry, but consistently after supposed “inclusion.” In Germany for instance, a new Integration Law gives the state power to determine where refugees can live – either by allocating or banning them from certain areas; this will supposedly “avoid the emergence of social hotspots.”

The effects are in fact to place people under a glare of general suspicion until they prove otherwise. Migrants are in turn deprived of the self-evident fundamental right of the freedom to choose where they live. Thus institutionalizing the “exclusionary incorporation” of migrants; the relative lack of educational and employment opportunities, the residential segregation, the public media denigrations, the police profiling, the public humiliations etc. This ensures that they remain second-class citizens and on the margins of the economy, despite being granted citizenship or asylum.

December 9, 2016

Kabila’s impasse

Joseph Kabila, image via MONSUCO Flickr.

Joseph Kabila, image via MONSUCO Flickr.There is a nervous crescendo building up on the streets of Kinshasa ahead of December 19, the day President Joseph Kabila is supposed to step down. Diplomats are sending their families on early Christmas vacations and the Congolese franc has depreciated by about 25 per cent against the US dollar. On social media and even in the streets, signs of “Bye Bye Kabila” and “Eloko Nini Esilaka Te?” (What thing never ends?) denounce what is increasingly looking like a power grab: Although scheduled to leave office after 15 years at the helm, Kabila and his administration have created artificial delays in the electoral process, making it impossible to hold presidential elections on time. Public protest in response to these delays has been suppressed often violently. In September, police and presidential guards cracked down on protests in the poor northwestern neighborhoods of Limete, Masina, and Matete, with tear gas and live bullets, killing at least 53.

It would be easy to look at the streets of Kinshasa and think that we’ve seen this before: A president clinging to power, restive and frustrated youth, streets barricaded with burning tires, and abusive soldiers cuffing, beating, and taking what they want. The Congo is a generous purveyor of African stereotypes, often making it difficult to see the politics through the thickets of hyperbole.

But there is something new afoot, making this uncharted territory. The country has never seen a peaceful, democratic transfer of executive power in its history. There is no Léopold Senghor or Julius Nyerere – leaders who were in power for over twenty years but eventually stepped down peacefully – to serve as a model or blueprint for how to navigate this turbulence.

At the core of the impasse is the political future of Kabila. Parachuted into power following his father Laurent’s assassination in January 2001, Kabila cuts an enigmatic figure. A reclusive president who dislikes the public stage, he presided over the reunification of the country after the war and has overseen an average GDP growth of more than 6% since 2010. Notwithstanding, he has done little to reform an abusive state apparatus or spread economic growth – which is largely driven by industrial mining – more evenly.

Only 45 years old, Kabila now faces an extremely uncertain political future. At times over the past two years, various members of his inner circle have floated the idea of changing the constitution to allow him to run for a third term; after all, this is what Presidents Denis Sassou Nguesso and Paul Kagame did last year, and what Yoweri Museveni, Sam Nujoma, and Paul Biya did in years past. These ideas have been met with fierce opposition from the Catholic Church, the international community, and civil society. In a nationwide opinion poll conducted jointly by the Congo Research Group, where I work, and the Congolese polling firm BERCI, 81% of respondents said they were against a constitutional revision. Kabila seems to have abandoned this approach for now.

He does not have many other options. Having used political fragmentation and weakness as a means of rule for more than a decade, Kabila has become a victim of his own strategy. He is now confronted with an extremely fractious inner circle, in which no one is both popular and loyal enough to be a viable successor. Advisors say that he is worried that if he names someone, his coterie will erupt in infighting. In our poll, when asked whom they would vote for if elections were held this year, only 7.8% named Kabila. And only 17.5% said they would vote for an individual who is currently in the ruling coalition.

This leaves Kabila dead-ended. Unable to change the constitution and lacking a dauphin, he is forced to play for time – a strategy known as glissement (slippage). Members of government are experts at stalling. The government only disbursed 15% of the election budget in 2012, and 25% in 2013 and 2014, making it difficult for the electoral commission to do its job. Several rounds of negotiations have also been a means of co-opting opponents and playing for time, first in the wake of the deeply flawed 2011 elections and most recently with the dialogue politique, which culminated in a deal with opposition politicians that offered them the prime ministry in return for postponing elections until April 2018.

However, the two most popular politicians in the country have boycotted this deal. In our poll, Moise Katumbi, the wealthy former governor of Katanga province won 33% of the potential vote and Etienne Tshisekedi, the veteran opposition leader, 17%. They are now planning a series of nationwide protests aimed at unseating Kabila.

A resolution of this crisis is not likely soon. Katumbi, who left for exile when the government issued a dubious arrest warrant for him in May 2016, is barred from negotiations, and Tshisekedi is not known for compromise. They are bolstered by an energized donor community, which has threatened sanctions – the US has already imposed a travel ban and asset freezes on three security officials – and has been uncharacteristically united. On the other hand, Kabila appears to believe that he can muddle his way through by repressing street protests and hiving off opponents with money and positions in government. Last month he named a former Tshisekedi loyalist prime minister, and diplomats suspect that part of the drop in the Congolese franc has to do with “patronage inflation” – the premium Kabila has to pay for loyalty during this crisis. There do not seem to be any divisions within the security services that could present a physical threat to himself or his government.

Meanwhile, his African peers, after some wavering, appear also to be grudgingly backing him. A summit of regional leaders met in Luanda this week and endorsed the deal that Kabila had hashed out with the opposition. South Africa has been particularly feckless: though it brokered the historic 2002 peace deal, its current leadership has remained silent in face of the turmoil in Kinshasa.

Over the next two years, the Congolese political system will enter a new phase, with a new relationship between the population and its elites. The framework of the past 13 years was defined by a peace process that culminated in a new constitution, the Third Republic, which forged new democratic institutions and set the terms for political competition. The current impasse is testing that document to its core. It will either be jettisoned, or maimed to such a degree that it will be nothing more than a series of laws, or will survive as a stronger, sturdier foundation.

December 8, 2016

Africa Is a Country is joining Jacobin, and needs your help!

Dear readers,

We are happy to announce today, that Africa is a Country is joining the Jacobin family of publications.

We couldn’t be more excited about this new partnership!

Over the past five years, Jacobin has become the leading intellectual voice of the American left. But more than that it has invigorated intellectual culture online. Jacobin’s achievements have also been noted in features in The New York Times, The Hindu, and the Guardian, among others.

For almost nine years, Africa is a Country has been doing much of the same, on a smaller scale, for coverage of Africa and African politics and culture. We started as an outlet for founder and editor Sean Jacobs to challenge the received wisdom about Africa from a left perspective, informed by his experiences of resistance movements to Apartheid. Since then we have grown in size to include a larger geographic scope and, crucially, launched the careers of a number of young African and diaspora writers, scholars and artists to a point where as the South African newspaper Mail & Guardian concluded: “Try as you might, it is hard not to turn an online corner in Africa without bumping into Africa is a Country.” All of this has been done with contributors and editors putting in long volunteer hours.

As part of the Jacobin family, the editorial direction of Africa is a Country will largely remain the same. However, with more resources and help, we will be able to grow as a publication and organization. One major project we are hoping to pull off in the next year or so is the launching of the Africa is a Country print magazine. Our coverage on the site will reflect this direction, as it will be more thematically oriented. Moving in this new direction will require even more resources, which is where you our loyal readers come in.

During our nine year run, we haven’t asked for much from you. However, today we are going to make that ask. For our initial fundraising goal we would like to raise $10,000 by the end of December.

Around this holiday season, please consider giving to Africa is a Country, so that we can continue bringing you the new perspectives from across the continent. United States donations are tax-deductible and can be sent either online here or via check to Jacobin Foundation, 388 Atlantic Avenue, Brooklyn NY 11217. Please include “Africa Is a Country” in the memo line if mailing in your contribution.

Africa Is a Country needs your money!

Dear readers,

We are happy to announce today, that Africa is a Country is joining the Jacobin family of publications.

We couldn’t be more excited about this new partnership!

Over the past five years, Jacobin has become the leading intellectual voice of the American left. But more than that it has invigorated intellectual culture online. Jacobin’s achievements have also been noted in features in The New York Times, The Hindu, and the Guardian, among others.

For almost nine years, Africa is a Country has been doing much of the same, on a smaller scale, for coverage of Africa and African politics and culture. We started as an outlet for founder and editor Sean Jacobs to challenge the received wisdom about Africa from a left perspective, informed by his experiences of resistance movements to Apartheid. Since then we have grown in size to include a larger geographic scope and, crucially, launched the careers of a number of young African and diaspora writers, scholars and artists to a point where as the South African newspaper Mail & Guardian concluded: “Try as you might, it is hard not to turn an online corner in Africa without bumping into Africa is a Country.” All of this has been done with contributors and editors putting in long volunteer hours.

As part of the Jacobin family, the editorial direction of Africa is a Country will largely remain the same. However, with more resources and help, we will be able to grow as a publication and organization. One major project we are hoping to pull off in the next year or so is the launching of the Africa is a Country print magazine. Our coverage on the site will reflect this direction, as it will be more thematically oriented. Moving in this new direction will require even more resources, which is where you our loyal readers come in.

During our nine year run, we haven’t asked for much from you. However, today we are going to make that ask. For our initial fundraising goal we would like to raise $10,000 by the end of December.

Around this holiday season, please consider giving to Africa is a Country, so that we can continue bringing you the new perspectives from across the continent. United States donations are tax-deductible and can be sent either online here or via check to Jacobin Foundation, 388 Atlantic Avenue, Brooklyn NY 11217. Please include “Africa Is a Country” in the memo line if mailing in your contribution.

Africa is a Country joins Jacobin!

Dear readers,

We are happy to announce today, that Africa is a Country is joining the Jacobin family of publications.

We couldn’t be more excited about this new partnership!

Over the past five years, Jacobin has become the leading intellectual voice of the American left. But more than that it has invigorated intellectual culture online. Jacobin’s achievements have also been noted in features in The New York Times, The Hindu, and the Guardian, among others.

For almost nine years, Africa is a Country has been doing much of the same, on a smaller scale, for coverage of Africa and African politics and culture. We started as an outlet for founder and editor Sean Jacobs to challenge the received wisdom about Africa from a left perspective, informed by his experiences of resistance movements to Apartheid. Since then we have grown in size to include a larger geographic scope and, crucially, launched the careers of a number of young African and diaspora writers, scholars and artists to a point where as the South African newspaper Mail & Guardian concluded: “Try as you might, it is hard not to turn an online corner in Africa without bumping into Africa is a Country.” All of this has been done with contributors and editors putting in long volunteer hours.

As part of the Jacobin family, the editorial direction of Africa is a Country will largely remain the same. However, with more resources and help, we will be able to grow as a publication and organization. One major project we are hoping to pull off in the next year or so is the launching of the Africa is a Country print magazine. Our coverage on the site will reflect this direction, as it will be more thematically oriented. Moving in this new direction will require even more resources, which is where you our loyal readers come in.

During our nine year run, we haven’t asked for much from you. However, today we are going to make that ask. For our initial fundraising goal we would like to raise $10,000 by the end of December.

Around this holiday season, please consider giving to Africa is a Country, so that we can continue bringing you the new perspectives from across the continent. United States donations are tax-deductible and can be sent either online here or via check to Jacobin Foundation, 388 Atlantic Avenue, Brooklyn NY 11217. Please include “Africa Is a Country” in the memo line if mailing in your contribution.

December 7, 2016

What happens in the DRC after December 19th

Image via The White House

Image via The White HouseThe presidential term of Joseph Kabila, in power in the Democratic Republic of Congo since 2001, is suppose to end in less than two weeks on December 19th. Kabila is barred from running for another term. The next day Congo should have a new government.

For the last year, opposition groups have demanded the electoral commission organize elections. They have mostly met with violence and obfuscation. At least 100 people have been killed in protests in 2016 and hundreds more arrested. Opposition party offices have been torched and one of the opposition candidates have been forced to flee the country. Meanwhile, Kabila’s party insist that no election can happen until 8 million potential new voters are added to the voters roll, knowing full well this could take years.

Joseph Kabila took power — he wasn’t elected; he inherited the office — in January 2001 after the assassination of his father Laurent D. Kabila while nearly half of the country was occupied by foreign troops and rebels. Among the foreign armies on the ground in the Congo, were Rwandan and Ugandan troops who earlier helped Laurent Kabila take power in May 1997. Following disagreements between Laurent Kabila and his former Rwandan and Ugandan allies who warned him against becoming too independent, the latter wound up occupying a large part of Congolese territory along with rebel groups.

The Congolese met in the South African resort, Sun City, to find a solution to the country’s crisis. They drafted a constitution accepted by referendum in December 2005 and promulgated on February 18, 2006. According to article 70 of the Constitution, the president of the republic is elected by a direct, general vote for a five year term that is renewable once. Article 220 of the Constitution is a safeguard stipulating that “… the term length of the President of the Republic” cannot be subject to constitutional revision.

In 2006, Joseph Kabila was elected for a five-year term. Before the 2011 elections, Kabila changed the rules of the game by imposing a single round of elections. This was made possible by paying large sums of money to members of the Congolese parliament. In so doing, Kabila trampled on the Congolese constitution and disregarded the separation of executive and legislative powers. The 2011 elections were particularly flawed and lacked transparency. Despite the objections by the Catholic Church of the Congo, the Carter Center, and the European Union over numerous electoral irregularities, the CENI declared Joseph Kabila the “winner.”

The country plunged into a grave political and institutional crisis. Nevertheless, the opposition expected Kabila to organize new elections at the end of his second and final term, leave power, and make way for a new president. Instead, Kabila stepped up his delay tactics in order to avoid holding elections. That’s when his excuses started. At the same time, he revived an old project to double the number of provinces, adding to the challenge of holding elections. Understanding this climate gives context to the current crisis.

There are currently two camps in conflict. On one side is the Rassemblement, which consists of the following political parties: the UDPS of veteran politician Etienne Tshisekedi; the G7 supporting football club owner and former governor of Katanga province, Moise Katumbi; Congo Na Biso (“Our Congo”) of Freddy Matungulu; the Dynamique de l’Opposition; and l’Alternance pour la République. Tshisekedi’s Rassemblement argues that Kabila is primarily to blame for the current political crisis and thus cannot take part in its resolution. Therefore, the Rassemblement is calling for inclusive talks to determine the conditions and means for Joseph Kabila’s departure from the presidency later this month. The Rassemblement also seeks to select an interim President until new elections can be held and seeks to find the technical and financial means for instituting a new electoral schedule and planning the next election.

On the other side are Joseph Kabila and his supporters, who want to keep the incumbent in power past December 19, 2016, in violation of article 75. Article 75 states that: “In the case of a vacancy, as a result of death, resignation or any other cause of permanent incapacitation, the functions of the President of the Republic … are temporarily discharged by the President of the Senate.” Nevertheless, the Congolese president held talks, led by African Union mediator Edem Kodjo, a Togolese diplomat, on the crisis. Only a small portion of the opposition, which included Vital Kamerhe a former ally of President Kabila and president of the Union pour la Nation Congolaise, participated in the talks. The Rassemblement did not join in the talks for several reasons, including, firstly, the rejection of Kodjo who is seen as being too close with the presidential majority; second, the government’s current judicial proceedings against Moise Katumbi who is in exile in the United States (the government accuses him of hiring mercenaries and sentenced him, in absentia, to three years in jail for fraud); and, finally, the government’s incarceration of political prisoners and a media blackout. The Catholic Church who initially participated in the talks withdrew following bloody protests in September 2016.

Despite the fact that the main political parties did not participate in these talks, Edem Kodjo continued consulting with a very fringe part of the opposition and reached a political accord that allows Kabila to remain in power after the end of his term this year. In exchange for accepting what the Congolese people are calling glissement, the French word for “slippage,” Vital Kamerhe was expected to be named Prime Minister. Instead, on November 17, Kabila gave the position to Samy Badibanga, who had been excluded from the UDPS in 2012.

Observers of Congolese politics note that the political accord reached by Kodjo and Badibanga’s nomination do nothing to resolve the country’s crisis. With the support of the US, the European Union, and the UN, the Catholic Church of the Congo continued engaging in consultations with the Kabila camp and Rassemblement.

On December 2, the Catholic Church proposed that the presidential majority (MP) and the Rassemblement coalition meet, in a less formal setting, to discuss their differences. Such discussions would focus on adherence to the Constitution, the electoral process (including the scheduling of elections), the functioning of institutions during the transition, or what a possible political compromise might look like.

Joseph Kabila visited with Catholic bishops on Monday, December 5, and the question remains whether the Congolese president will make any concessions with respect to the Rassemblement’s positions. The Catholic Church insists that this is a critical hour and has called for all parties to share responsibility and exercise good political will in order to keep the country from falling into an out of control situation.

The Rassemblement is bound to spill out onto the streets on December 19 to demand that Kabila abide by the constitution and step down from office. Maman Sambo Sidikou, the head of MONUSCO, told the United Nations that there are real dangers in DR Congo’s descent into chaos.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers