Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 291

January 20, 2017

Music Break No.102–Winter In America edition

“… The stakes are very high: literally, survival of organized human society in any decent form,” Noam Chomsky tells Brooklyn Rail, as the former British colony of the United States of America, inaugurates its 45th president. So, this weekend’s Music Break goes out to our American family, who are set to face four years of struggle against a new set of rulers, led by “a mendacious and cathartic white president.” The decisions made in the nation with the largest military, some of the biggest corporations and the loudest media companies in the world, effect us all.

But let’s not be too quick to panic. If American citizens are firm in their resistance, the regime will be checked by a balance of powers and precedent (we’d recommend some political history, e.g. Corey Robin and Stephen Skowronek) and an law making and enforcement regime that is spread between 50 semi-autonomous states (though those states are equally important in introducing retrogressive laws around trade union organizing, abortion or sexual rights).

For starters, you can play these sounds to drown out the noise of Donald Trump’s inauguration speech today.

Music Break No. 102 – Winter in America edition

January 19, 2017

African inequality rising

Bean harvest in Ethiopia. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Bean harvest in Ethiopia. Image via Wikimedia Commons.Witness Nigeria. The African goliath has in recent years climbed steadily through the ranks of the UN’s Human Development Index, a global index of key development indicators such as income, literacy and life-expectancy. But Nigeria’s success in the HDI disguises a widening gulf between the haves and the have-nots. In fact, when Nigeria’s latest placement in the index is adjusted for income inequality, it falls nine places – three more than in 2010. In other words, the living standards of the Nigerian elite have raced far ahead of the quality of life of the majority.

Indeed, according to the HDI, every country in Africa is today less equal than it was in 2010; for the African masses, in other words, the trickle-down benefits of economic growth have been relatively small. But the story of inequality in Africa is more complex than that of a widening gulf between the very rich and the very poor. African Women, in particular, have shouldered a disproportionately heavy burden. The UNDP estimates, for example, that African women earn only seventy cents on their male peer’s wage dollar, and attain only 87 per cent of the development outcomes of men.

The causes of rising inequality in Africa are a matter for debate. But as Branko Milanovic shows in his excellent book Global Inequality – as in the West, so in Africa, the concentration of wealth in the hands of the few is a long-run global trend. As Milanovic and others argue, Africa’s recent lurch towards inequality is, as it were, the “natural” outcome of an increasingly capital-driven market economy. But the markets which have emerged in the last two decades are not spontaneous or organic creations; they have architects.

Major Western donor governments and international lending institutions, in particular, spearheaded neoliberal reforms in Africa which spur headline GDP growth but drive inequality. While Western governments unraveled the welfare state in their own countries in the 1980s and ‘90s, they forced their African counterparts to emulate their retrenchment agenda through loan and aid conditions. Under the influence of Western donors, austerity became African leaders default coping mechanism for periods of global economic stress.

The cure for economic stagnation, in other words, became the cause of a new pathology: austerity. Never was this truer in Africa than after the 2007-08 financial crisis. World demand for Africa’s exports collapsed, Foreign Direct Investment fell away and the cost of servicing dollar-debt rose after the 2007-2008 financial crisis; African governments responded – as their western creditors insisted – with spending cuts. The cut-backs buoyed macro-economic growth rates, but entrenched inequality, so much so that the IMF acknowledged it had overestimated the value of structural adjustment.

Increasingly, development in the form of retrenchment and chasing GDP growth has become a kind of madness: the cure for poverty creates more obstacles to economic growth than it overcomes. In Ethiopia, for example, officials post 12% annual GDP growth rates, while tens of millions of Ethiopians find themselves on the cusp of starvation. As René Lefort observed, the cause lies not in Ethiopia’s levels of food production – the country produces enough cereal to feed the entire population – but in the disproportionate impact poor harvests and price rises have on Ethiopia’s agricultural wage-laborers.

By prioritizing high-yield, industrial agricultural practices and diverting resources to manufacturing, the EPLF – Ethiopia’s ruling party – has left great swathes of the population to starve without access to land or income. But such extreme inequality has driven popular protest in Ethiopia in recent months, which has shut down factories, stalled foreign investment and crippled infrastructure.

Is Ethiopia a bellwether, a portent for Africa for the year ahead? It is an extreme case: its growth has been headier, its government’s commitment to development goals steelier than that of other African countries. But Ethiopia is not unique. This is an election year for a number of large African economies, including Angola, Algeria, Kenya, Rwanda and Sierra Leone; each faces a cocktail of falling commodity prices, international economic headwinds, isolationism and domestic polarization. As Joseph Warungu writes, many African governments enter 2017 in defensive mode. As events in Ethiopia, the US and Europe in 2016 have hinted, the fall-out from rising inequality promise to be problematic – as much in Africa as in the West.

January 18, 2017

Opening Angola’s past to public debate

Angola’s recent history is beset with conflict. Twenty-seven years of civil war (1975-2002) followed by thirteen years of anti-colonial war (1961-1974). Real political differences fueled these wars, compounded by foreign intervention and shifting control over precious natural resources that altered the calculus of conflict. The Luena Peace Accords of 2002 between the governing MPLA and the rebel UNITA movement brought an unsteady peace without reconciliation and ushered in an oil boom (one that has faltered in the past two years).

Angola’s recent history is beset with conflict. Twenty-seven years of civil war (1975-2002) followed by thirteen years of anti-colonial war (1961-1974). Real political differences fueled these wars, compounded by foreign intervention and shifting control over precious natural resources that altered the calculus of conflict. The Luena Peace Accords of 2002 between the governing MPLA and the rebel UNITA movement brought an unsteady peace without reconciliation and ushered in an oil boom (one that has faltered in the past two years).

The socialist ethos of Angola’s First Republic (1975-1992), and the civil war, kept the state focused on the horizon. As the Popular Republic of Angola, the ruling MPLA produced five-year plans and annual slogans to motivate production and bolster morale under difficult economic conditions. Independence meant that the miseries of colonialism were tidily prologued, and energies targeted present and future development. The 2002 “peace without reconciliation” model opted for a similar perspective: let the oil boom keep Angolan sights on new high rises to distract from body counts, betrayals and disappointments.

Even as the Angolan leadership is relentless in its future orientation, other Angolans have taken up the peace to dig into the past. The year 2015 marked the 40th anniversary of Angolan Independence. The Associação Tchiweka de Documentação (Tchiweka Association for Documentation –Tchiweka was the nom de guerre of Lúcio Lara) and Geração 80 (80s Generation, in this case: Mário Bastos, Jorge Cohen, Kamy Lara, and Tchiloia Lara) launched the film Independência.

Independência Trailer

This film is the result of six years of work by a team of media producers and an historical consultant, Dr. Maria de Conceição Neto, all of them associated directly or indirectly with the MPLA, and headed up by Paulo Lara, a former guerrilla fighter, general in the Angolan Armed Forces, and the son of Lúcio Lara (a founding member of the MPLA and a key figure in Angola’s independence struggle). They produced not only a film, but also more than 1,000 hours of interviews with more than 600 participants of the armed struggle for Angola’s independence. This was not just a film, but a project: Project Angola – Pathways to Independence. And the project is a signal achievement, the film a door to conversations about this critical period in Angola’s past.

Independência screened in Luanda, Malange, Benguela, and Viana beginning in late 2015 and throughout 2016. I saw it Luanda and Lisbon. Typically, Bastos and some of the research and production crew were present at screenings. The idea being that the film is an invitation to dialogue, not the last word on independence.

Film director Mário Bastos explains that the film is but one of many that have emerged from this vast new archive. It is one that speaks from the point of view of participants, but that is pitched to an audience of those, like Bastos, born after 1975. In this sense, the film is an intergenerational act of collective story-telling and history making. Unlike the memories recounted in homes, at Saturday afternoon funges, the film is systematic in piecing together the fragments of memory with archival documents and footage. It begins with memories of the late colonial period, the early days of clandestine organizing, and then moves to the development of the different movements and the armed struggle in exile and in the Angolan interior.

Independência brings together the stories of those who fought on the frontlines, those who were imprisoned (and the stories of the prisons themselves, rarely recounted), and those who were involved in clandestine support for the movements. It shines when it shows us small moments of humanity: Rodeth Gil recounting her fear of swimming. Or for tackling sticky historical questions of memory, like the story of a brutal beating of a prisoner at Missombo prison camp, nightmarishly etched in prisoners’ memories but without documentary record. Importantly, the film reminds us of the fear with which people lived under the colonial regime. Independência also expands the cast of characters typically associated with the struggle for independence. It has an equalizing force, showing “Kiluanji,” a fabled soldier and UNITA general Samuel Chiwale, recounting their memories and experiences alongside Augusto Loth, a nurse, largely unknown to the average Angolan.

Unita, still from film.

Unita, still from film.The film, and its beautiful DVD version (which includes a short film on memory and another on the making of the film), attend to the past’s difference, its pastness. Bastos’s camera plays with materiality, the flatness of documents, their capacity to betray, the noble quietness of photos, and the digital/analog interface. As someone who has spent many hours with PIDE (Portuguese secret police) documents and many hours conducting interviews, tangling with the complications of reminiscence and of the archival fragment, I appreciated the way the film uses memory to, literally sometimes, re-write the past and contest its interested traces.

Noted Angolan musician Victor Gama crafted a soundtrack that is poignant and historically precise. The film is narrated by writer and musician Kalaf Epalanga whose bass-toned voice but straightforward delivery strike just the right tone for my ear. Elizângela Rita does the narration for Deolinda Rodrigues, one of the five heroines killed in 1969 at the hands of the FNLA after being trained by Cuban soldiers and led into Angola by “Ingo” Vieira Lopes for a reconnaissance mission. Deolinda’s diaries were posthumously published in the early 2000 and offer rich, reflective material and an insider´s critique of the MPLA and its masculinism.

The idea to screen the film in various locales within Angola as well as where its diasporas live and congregate, is its great promise. The film has its limitations too. One friend thought Mário Pinto de Andrade’s role in the founding of the MPLA had been underplayed (I was happy it was mentioned at all); another thought Viriato de Cruz got short shrift. Others may think that Jonas Savimbi (an ally of the U.S. and Apartheid South Africa) and Holden Roberto (close to neighboring Zaire’s Mobutu) don’t get their due. Some viewers will dispute the experience of particular participants. But the film, and, more significantly, the Project, have left an open invitation to conversation and to greater engagement with this critical moment in Angola’s past – one in which even as there was political division, there was also agreement on the desire for independence. Like the recent spate of books on the 27 de Maio (the massacre of MPLA dissidents in 1977), they have re-opened the past to public debate and not just whispers and conversations between friends.

* Independencia will screen at the Pan-African Film Festival in L.A. in February 2017.

January 17, 2017

Patrice Lumumba (1925–1961)

Patrice Lumumba (center) in 1960. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Patrice Lumumba (center) in 1960. Image via Wikimedia Commons.Patrice Lumumba was prime minister of a newly independent Congo for only seven months between 1960 and 1961 before he was murdered, fifty-six years ago today. He was thirty-six.

Yet Lumumba’s short political life — as with figures like Thomas Sankara and Steve Biko, who had equally short lives — is still a touchstone for debates about what is politically possible in postcolonial Africa, the role of charismatic leaders, and the fate of progressive politics elsewhere.

The details of Lumumba’s biography have been endlessly memorialized and cut and pasted: a former postal worker in the Belgian Congo, he became political after joining a local branch of a Belgian liberal party. On his return from a study tour to Belgium arranged by the party, the authorities took note of his burgeoning political involvement and arrested him for embezzling funds from the post office. He served twelve months in prison.

Congolese historian Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja — who was in high school during Lumumba’s rise and assassination — points out that the charges were trumped-up. Their main effect was to radicalize him against Belgian racism, though not colonialism. Upon his release in 1958, Lumumba, by now a beer salesman, was more explicit about Congolese autonomy and helped found the Congolese National Movement, the first Congolese political group which explicitly disavowed Belgian paternalism and tribalism, called unreservedly for independence, and demanded that Congo’s vast mineral wealth (exploited by Belgium and Euro-American multinational firms) benefit Congolese first.

For Belgian public opinion — which played up Congolese ethnic differences, infantilized Africans, and in the late 1950s still had a thirty-year plan for Congolese independence — Lumumba and the Congolese National Movement’s pronouncements came as a shock.

Two months after his release from prison, in December 1958, Lumumba was in Ghana, at the invitation of President Kwame Nkrumah who had organized the seminal All Africa People’s Conference. There, as a number of other African nationalists pushing for political independence listened, Lumumba declared:

The winds of freedom currently blowing across all of Africa have not left the Congolese people indifferent. Political awareness, which until very recently was latent, is now becoming manifest and assuming outward expression, and it will assert itself even more forcefully in the months to come. We are thus assured of the support of the masses and of the success of the efforts we are undertaking.

The Belgians reluctantly conceded political independence to the Congolese, and two years later, following a decisive win for the Congolese National Movement in the first democratic elections, Lumumba found himself elected to prime minister and with the right to form a government. A more moderate leader, Joseph Kasavubu, occupied the mostly ceremonial position of Congolese president.

On June 30, 1960, Independence Day, Lumumba gave what is now considered a timeless speech. The Belgian king, Boudewijn, opened proceedings by praising the murderous regime of his grandfather, Leopold (eight million Congolese died during his reign from 1885 to 1908), as benevolent, highlighted the supposed benefits of colonialism, and warned the Congolese: “Don’t compromise the future with hasty reforms.” Kasavubu, predictably, thanked the king.

Then Lumumba, unscheduled, took the podium. What happened next has become one of the most recognizable statements of anticolonial defiance and a postcolonial political program. As the Belgian writer and literary critic Joris Note later pointed out, the original French text consisted of no more than 1,167 words. But it covered a lot of ground.

The first half of the speech traced an arc from past to future: the oppression Congolese had to endure together, the end of suffering and colonialism. The second half mapped out a broad vision and called on Congolese to unite at the task ahead.

Most importantly, Congo’s natural resources would benefit its people first: “We shall see to it that the lands of our native country truly benefit its children,” said Lumumba, adding that the challenge was “creating a national economy and ensuring our economic independence.” Political rights would be reconceived: “We shall revise all the old laws and make them into new ones that will be just and noble.”

Congolese congressmen and those listening by radio broke out in applause. But the speech did not sit well with the former colonizers, Western journalists, nor with multinational mining interests, local comprador elites (especially Kasavubu and separatist elements in the east of the country), the United States government (which rejected Lumumba’s entreaties for help against the reactionary Belgians and the secessionists, forcing him to turn to the Soviet Union), and even the United Nations.

These interests found a willing accomplice in Lumumba’s comrade: former journalist and now head of the army Joseph Mobutu. Together they worked to foment rebellion in the army, stoke unrest, exploit attacks on whites, create an economic crisis — and eventually kidnap and execute Lumumba.

The CIA had tried to poison him, but eventually settled on local politicians (and Belgian killers) to do the job. He was captured by Mobutu’s mutinous army and flown to the secessionist province of Katanga, where he was tortured, shot, and killed.

In the wake of his murder, some of Lumumba’s comrades — most notably Pierre Mulele, Lumumba’s minister of education — controlled part of the country and fought on bravely, but was finally crushed by American and South African mercenaries. (At one point Che Guevara traveled to Congo on a failed military mission to aid Mulele’s army.)

That left Mobutu, under the guise of anticommunism, to declare a one-party, repressive, and kleptomanic state, and govern, with the consent of the United States and Western governments, for the next thirty-odd years.

In February 2002, Belgium’s government expressed “its profound and sincere regrets and its apologies” for Lumumba’s murder, acknowledging that “some members of the government, and some Belgian actors at the time, bear an irrefutable part of the responsibility for the events.”

A government commission also heard testimony that “the assassination could not have been carried out without the complicity of Belgian officers backed by the CIA, and it concluded that Belgium had a moral responsibility for the killing.”

Lumumba today has tremendous semiotic force: he is a social media avatar, a Twitter meme, and a font for inspirational quotes — a perfect hero (like Biko), untainted by any real politics. He is even free of the kind of critiques reserved for figures like Fidel Castro or Thomas Sankara, who confronted some of the inherent contradictions of their own regimes through antidemocratic means.

As such, Lumumba divides debates over political strategy: he is often derided as a merely charismatic leader, a good speaker with very little strategic vision.

For example, in the famed Belgian historical fiction writer David van Reybrouck’s much-praised Congo: An Epic History of a People, Lumumba is characterized as a poor tactician, unstatesmanlike, and more interested in rebellion and adulation than governance. He is faulted for not prioritizing Western interests.

Lumumba’s denunciation of the Belgian king in June 1960, for example, only served to embolden his enemies, argues Van Reybrouck. Lumumba is also criticized by his Western critics for turning to the Soviet Union after the United States had spurned him.

But as the writer Adam Shatz has argued: “It’s not clear how . . . in his two and a half months in office, Lumumba could have dealt differently with a Belgian invasion, two secessionist uprisings, and a covert American campaign to destabilize his government.”

More powerful perhaps is how Lumumba operates unproblematically as a figure of defiance. As the disappointment with national liberation movements in Africa (in particular, Algeria, Angola, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, and more recently South Africa’s African National Congress) sets in, and new social movements (#OccupyNigeria, #WalktoWork in Uganda, the more radical #FeesMustFall and struggles over land, housing, and health care in South Africa) begin to take shape, references to and images of Patrice Lumumba serve as a call to arms.

In Lumumba’s native Congo, ordinary citizens are currently fighting President Joseph Kabila’s attempts to circumvent the constitution (his two terms were up in December, but he refused to step down). Hundreds have been killed by the police and thousands arrested. Kabila, who inherited the presidency from his father, who overthrew Mobutu, exploits the weakness of the opposition, especially the power of ethnicity (via patronage politics) to divide Congolese politically. In this, Kabila is merely emulating the Belgian colonists and Mobutu.

Here Lumumba’s legacy may be helpful. Lumumba’s Congolese National Movement was the only party offering a national — rather than ethnic — vision and a means to organize Congolese around a progressive ideal. Such a movement and such politicians are in short supply in Congo these days.

But Lumumba’s story offers not just an invitation to revisit the political potential of past movements and currents, but also opportunities to refrain from projecting too much onto leaders like Lumumba who had a complicated political life and who did not get to confront the messiness of postcolonial governance. It also means treating tragic political leaders as humans. To take seriously political scientist Adolph Reed Jr’s advice about Malcolm X:

He was just like the rest of us — a regular person saddled with imperfect knowledge, human frailties, and conflicting imperatives, but nonetheless trying to make sense of his very specific history, trying unsuccessfully to transcend it, and struggling to push it in a humane direction.

It is perhaps then that we can begin to make true Patrice Lumumba’s critical wish, perhaps as self reflection, that he wrote in a letter from prison to his wife in 1960:

The day will come when history will speak. But it will not be the history which will be taught in Brussels, Paris, Washington or the United Nations. It will be the history which will be taught in the countries which have won freedom from colonialism and its puppets. Africa will write its own history and in both north and south it will be a history of glory and dignity.

January 16, 2017

Martin Luther King Jnr., Pan-African

Martin Luther and Coretta Scott King in Ghana in March 1957. Image: LIFE Magazine.

Martin Luther and Coretta Scott King in Ghana in March 1957. Image: LIFE Magazine.Last night, on the eve of Martin Luther King Jnr. Day, an official holiday here in the U.S., I felt the impulse to go in search of references to MLK’s engagement with the African continent. Starting from when he was a guest of Prime Minister Kwame Nkrumah at Ghana’s independence in March 1957, where he told Richard Nixon (representing President Dwight Eisenhower): “I want you to come visit us down in Alabama where we are seeking the same kind of freedom the Gold Coast is celebrating.”

A few weeks later, back in the U.S., he gave a sermon “The Birth of a New Nation,” in Montgomery, Alabama, about his trip to Ghana. It is first class. It is part popular history of Ghana, a recounting of its independence struggle, what lessons for African-American struggle (“Ghana has something to say to us. It says to us first, that the oppressor never voluntarily gives freedom to the oppressed”), and, crucially, the challenges represented by the postcolonial (“This nation was now out of Egypt and had crossed the Red Sea. Now it will confront its wilderness. Like any breaking aloose from Egypt, there is a wilderness ahead.”). It is worth revisiting.

In 1960, in Atlanta, Georgia, King met with Kenneth Kaunda, then the leading anticolonial leader in Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia). Kaunda went onto play a crucial in liberation struggles in Southern Africa (Namibia, South Africa, Zimbabwe). Which is fitting that the second King speech I read, dealt with the topic was Apartheid South Africa. This speech delivered by King in in London in 1964 on his way to receive his Nobel Peace Prize. This speech is shorter, but just as powerful. It name-checks Albert Luthuli, Nelson Mandela and Robert Sobukwe. Significantly, King talks about how he “understands” the turn to armed struggle as well as calls for sanctions against South Africa. (The reference to armed struggle also contradicts what is often a stock characterization of King favored by American conservatives and liberals and U.S. mainstream media.)

There is also a separate speech, also on South Africa, that King delivered the following year at Hunter College. It is also worth checking out, as King expands on many of the arguments of the London speech and extends his call for sanctions to Portugal, for its colonies and violent repression of Africans in Angola and Mozambique.

What emerges in these speeches by and interviews with King, including on a range of other topics (.e.g. U.S. foreign policy, Vietnam, racism), is how “from the beginning of his ministry, King was far more radical, especially on matters of labor, poverty, and economic justice, than we remember,” as a post on Jacobin reminds us.

Finally, I listened to a lost audio interview of December 1960, where King is interviewed in Chattanooga, Tennessee, and speaks about his 1957 trip to Ghana and his November 1960 trip to the inauguration of Nigeria’s first independent president. It is worth copying his whole answer to what he learned about those two trips:

There is quite a bit of interest and concern in Africa for the situation in the United States. African leaders in general, and African people in particular are greatly concerned about the struggle here and quite familiar with what has taken place. I just returned from Africa a little more than a month ago and I had the opportunity to talk with most of the major leaders of the new independent countries of Africa, and also leaders in countries that are moving toward independence. And I think all of them agree that in the United States we must solve this problem of racial injustice if we expect to maintain our leadership in the world and if we expect to maintain a moral voice in a world that is two thirds color … They are familiar with [conditions of black people in the United States] and they are saying in no uncertain terms that racism and colonialism must go for they see the two are as based on the same principle, a sort of contempt for life, and a contempt for human personality.

The market decides if we are free

Nana Akufo-Addo swears-in as Ghana’s newly-elected President. Image credit Stringer (Anadolu Agency/Getty Images)

Nana Akufo-Addo swears-in as Ghana’s newly-elected President. Image credit Stringer (Anadolu Agency/Getty Images)Before Nana Akufo-Addo’s inauguration as Ghana’s new President, the Financial Times sent its Africa correspondent to interview him. Akufo-Addo won Ghana’s presidential elections, on December 7, 2016, by a wide margin over incumbent John Dramani Mahama. The Financial Times report follows the typical prescription for foreign-correspondents-commenting-on-African-elections. Read it if you are bored. With slight condescension it uses the specter of corruption to frame the country’s political legacy. It wonders-warns about how the new leader will fare in a climate of political uncertainty. It fake-commands that he “must make good” on his promises. Mahama’s National Democratic Congress (NDC) is glossed as “left-leaning” and Akufo-Addo of the New Patriotic Party (NPP) as a “center-right wealthy technocrat,” who is too rich to be corrupted. The backhanded endorsement of Akufo-Addo comes not because of his skill or political courage, but because he already has enough money, which seems a willfully simplistic misunderstanding of the links between aesthetics and politics. The Financial Times’s focus on the personal characteristics and power of individuals and outdated tropes of African political fragility distract from the structural conditions of the Ghanaian state and, globally, the increasingly tenuous relationship between electoral politics and economics.

As both presidential candidates themselves pointed out, Ghanaian political-economic actors are limited in their ability to change conditions because of massive debt and the influence that foreign investors and loan-makers have over national production, consumption, and infrastructure. Even for the Financial Times, all that matters are macroeconomic indicators of fiscal stability. Understanding its ability to service debt and return on investment are the main reasons that most foreign observers are interested in Ghana.

There are substantive differences between Ghana’s two main political parties rooted in their respective histories, but to call the NDC left-leaning and the NPP center-right today distracts from the global power of free market thinking. Akufo-Addo’s NPP is the political descendant of the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC), which invited Kwame Nkrumah to lead the independence movement against British rule in the 1940s. The NPP follows its forebearers’ legacy with its explicit orientation towards facilitating free market capital through a decentralized state.

Nkrumah’s radical call for “Self-government Now” led to a split with the capitalist oriented UGCC that continues today. Nkrumahists wanted a centralized, socialist state; this radical position was later taken up by NDC founder Jerry John Rawlings, who led two coups d’etat in 1979 and 1983 and was later elected president in 1992 when Ghana returned to democratic rule. But Ghana entered into a Structural Adjustment Program in 1983, when Rawlings was still a purportedly left-leaning military leader. And since then state policy under various governments has been shaped by the goals of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) which advocate trickle-down development – making the country appear as a reliable place for foreign investment and loan repayment.

Despite their differing rhetorics, the two main political parties both valorize neoliberal economic policies focused on building a good global image and middle-class consumption practices as engines of progress. Indeed, as the 2016 elections have shown, Ghana’s main political-economic split has become a disagreement about how to gain advantage in the global free market with a clear recognition that, by design, post-independence international finance has disadvantaged Ghanaian economic actors at all levels by limiting border crossings and hampering access to capital.

The NDC folks are embarrassed by their candidate’s loss in 2016: the first time an incumbent president in the country’s history has been voted out of office. One party insider tells me that they should have won, but were arrogant and got complacent. Mahama seems more sanguine. In his farewell address, he stakes his legacy on his infrastructural successes. He marks his greatest accomplishments as developing roads, schools, electricity and water access. But for many, the beginning of the end of the Mahama regime was the crippling electricity load shedding by Electricity Corporation of Ghana (ECG) that went on for several years.

State policy since the 1980s – shaped by IMF and World Bank agreements – mandated privatizing state resources. Electricity, like other sectors, has been caught in this process: not fully state-run and not totally private. Unreliable power has harmed local businesses; and even when electricity is available most residential and commercial clients cannot pay market rate. But the Ghanaian state has seemed unconcerned, rather prioritizing state fiscal discipline and maximizing productivity of resources. As a World Bank official pointed out, more than 30% of electricity is lost in its circulation. Rather than focusing on providing cheap electricity to all, they advocate fighting illegal hook-ups and encourage policies that squeeze every last resource out of the poor to service state debt and make private profit. The ECG struggles to regulate its product, and is under pressure to make money and streamline service delivery; people’s needs drop out of the equation.

When Ghana recently attained lower-middle income status it increased its exposure to repaying loans. In a country rich in oil and gas resources, many blame inefficiency and corruption. But even with revenue from natural resources, the state is increasingly tied to the dictates of foreign capital. The state is forced into short-term borrowing to pay civil servant salaries and service older debt instead of investing in local people’s long-term productive capacities, creativity, health, education, and infrastructural needs.

Ghana is not exceptional in this regard. Nations like Ghana aspire to self-sufficiency but find that domestic policies and institutions are structured with an eye to marketing the nation to foreign investors whose goals are extracting resources and selling commodities rather than creating self-sufficient industries through long-term investment.

State and World Bank policy makers rely on macroeconomic indicators that see timely return on foreign investment and debt repayment as engines of growth. Macroeconomics also validate growing class divisions by celebrating the rise of a small entrepreneurial middle-class as an engine of national growth. Accra’s art and music scene and digital industries receive attention from global hipsters, tourists, and even the New York Times. Foreign investments fund highly-visible flashy infrastructure projects, with most construction done by multinational corporations who are locally criticized for importing skilled workers, equipment, and materials and leaving few resources behind. Meanwhile most working people in urban Ghana, such as traders, civil servants, laborers and teachers, do not benefit and cannot afford basic food, shelter, transportation and utilities with their earnings.

As wealth disparities grow in Ghana, and elsewhere, questions arise about the long-term effects of policies that focus on building unsustainable service and consumer economies. We continue to imagine nations as discrete entities that aim for state fiscal efficiency; but the lives of the nation’s citizenry are controlled through global financial networks. Rather than making sustainable conditions for people, policies reinforce growing inequality and continued dependence.

As the 2016 global cycle of elections shows, this is a moment of political anxiety. Elections in many locales mask finance capital’s influence by exacerbating national, racial, cultural, gender and class differences, rather than recognizing historical connections. Electoral politics create the illusion that a national populace shapes state policy, though publics are increasingly uncertain. The United States and Britain threaten to close borders due to racist and xenophobic fears over resource and job losses. A large segment of American voters are so alienated along race and class lines that they identify themselves in the anger and incoherence of demagoguery, turning to an irrational charismatic pundit who talks of fantastical past greatness to address anxieties about an uncertain future. Great Britain votes to remove itself from its closest economic allies, undercutting the flows of goods, resources, and labor that have built its economy in favor of a nostalgia for an ethno-nationalist singularity that also never was. These politics of nostalgia are forms of collective forgetting that erase histories of struggle and inequality.

But whereas in the U.S. and Europe there is a turn to isolationist national rhetoricians who dream on non-existent past glory, in Ghana, where the state is supposedly less stable and less in control of its borders and economic fate, people elect someone deemed a “technocrat” from an old political family, a lawyer who explicitly represents multiple fluencies and access to the power of finance capital. While Ghanaian governments have been forced to navigate an exploitative global financial landscape, perhaps their history of dealing with foreign influences can help reimagine a sustainable political future both within and against capital.

Supporters of the NPP are ecstatic at last weekend’s inauguration in Black Star Square. One campaigner explained to me they were in opposition so long that they had forgotten what being in power was like. Many people are grateful that the elections were peaceful and, as one Mahama voter told me, “we are now just proud to be Ghanaian.” As he takes the oath of office, Akufo-Addo looks the part of national leader. Although he has long been criticized for being overly western, always wearing a business suit, white shirt and cufflinks, he is resplendent in his chiefly regalia and elegant Kente cloth emblazoned with symbols of power and lineage. He carries the presidential sword, raising it above his head, a sign of his office.

From first president Nkrumah’s time, state ceremonies were modeled on the symbols and procedures of an Akan chief’s court as a way to blend established African ideas of sovereignty into the nation-state form. As Nkrumah was opposed to the power of Akan chiefs, he posited appropriating the nuanced ceremonial force of his enemies to help bring Ghanaians of all cultural-linguistic heritage together into a centralized socialist collective. Akufo-Addo, being of Akan royal heritage, dresses for power in a double sense, drawing on a centuries-long history of Akan political order and its more recent reinvention within a Ghanaian national idiom.

Akufo-Addo’s speech struck a presidential tone. But immediately after the ceremony, videos and memes start circulating of his speech intercut with speeches from which he seemingly plagiarized lines by Bill Clinton and George W. Bush, with Bush’s speech having drawn on one by Woodrow Wilson from 1913. When I first saw the video sent to me on WhatsApp, I was struck by how the elegance of Akufo-Addo’s delivery was enhanced, as his lines were immediately repeated by footage of Bush and Clinton from years earlier. This doubling created a rhetorical continuity and traces political connections to Clinton’s free trade doctrines and Bush’s neo-imperialism all put in the language of citizenship.

The sutured, cut-and-paste speech blended Akan, Ghanaian, and American signs of political power in a pastiche that announced the obligations and privileges of Ghanaian citizenship. Perhaps unintentionally the speech showed how in both the United States and Ghana ideological differences – Democrat and Republican, NPP and NDC – blur in the face of the power of the free market to shape worldviews; purportedly rational discourse is in fact a play of aesthetic differences. A further irony in drawing on Woodrow Wilson to celebrate Ghana is that Wilson’s political internationalism was underpinned by support for racial segregation and justifications for slavery. This has led to recent calls for the removal of his name from Princeton University’s School of Public and International Affairs. African nation-states were never supposed to be equal players on the global stage, but now claim sovereignty in the language of international finance; in this case literally doubling the speeches of American leaders that link citizenship to financial domination at the root of the free market. While American and European electorates rush to forget a past in which national wealth came through violences of the slave trade and imperial conquest, Ghana calls forth global linkages in the voice of Empire.

The inauguration captured how Ghanaian politics blends various traditions of rhetoric and sovereignty into a new mix. We cannot be distracted by the intents of charismatic personalities, but should ask ourselves what political aesthetics tell us about future alternative economic configurations dressed in the attire of the free market.

January 13, 2017

The long short history of Angola-Israel relations

Following the vote in favor of UN Security Council (UNSC) Resolution 2334 (2016) condemning illegal Israeli settlements of Palestinian territories and East Jerusalem, Israel cut diplomatic ties with 10 of the 15 member states that compose the UNSC. Israel reserved a specific retaliation for the UNSC’s two African member states: no more international development aid for Senegal and Angola. Interpreted as a largely symbolic move, Israel’s reaction to Angola is, however, in sync with the longer trajectory of Israeli/Angolan foreign relations.

These relations have been both material and symbolic. The relationship has two distinct phases. Hostile at first, it began with Angola’s independence and emplotment in the global Cold War. In the wake of the Cold War, Israel-Angolan relations morphed into a friendly and lucrative bond. Yet, some of the discourses and commitments of the first phase are cross-hatched into the second phase. Angola’s vote on UNSC resolution 2334 is the most recent example, although Israel’s public outrage is new.

First, a thumbnail sketch of Angola’s decolonization. The MPLA (Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola) declared Angola’s independence on November 11, 1975. Cuban troops and Soviet military hardware allowed them to hold off FNLA (National Front for the Liberation of Angola) forces bolstered by Zairean troops (and CIA funding) to the capital’s north. The MPLA had secured the city’s southern rim against a South African military invasion accompanied by a clutch of UNITA (National Union for the Independence of Angola) soldiers. In brief, independence, civil war and foreign intervention blossomed simultaneously.

The sociologist Jan Nederveen Pieterse noted that Israeli army brass helped plan the 1975 South African invasion of Angola. The strategy echoed that used by the Israelis to drive the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) out of Lebanon and the US strategy against the Nicaraguan Sandinistas (blamed for fomenting insurgency in El Salvador). In other words, this constituted part of a pattern of white settler states not only red-baiting but actively attacking liberation movements. The South African invasion of Angola further drew on Israeli counterterrorism strategies developed in the West Bank and Gaza. Counterinsurgency cooperation in Southern Africa thus lit up a network of politics that spanned the Middle East, Central America and Southern Africa.

International revolutionary movements built their own networks of solidarity, military support, and educational training. Southern African liberation movements (the MPLA, Mozambique’s FRELIMO, South Africa’s ANC, and Namibia’s SWAPO), for their turn, struggled to protect or achieve their sovereignty in the face of obstructionist white settler states and Apartheid policies. Various observers have reminded us of the similarities between Apartheid South Africa and Israeli occupation of Palestinian lands: population control, non-contiguous land areas, passbooks and special IDs, archipelagos of ethnicity, militarized states, torture, and terror. (Also not too distant, by the way, is the US history of Native American reservations.)

These white settler states acted in their own interests in the name of the Cold War. Israel, like South Africa, did not act as a proxy for US interests any more than Cuba acted at the behest of the Soviet Union (as Piero Gleijeses and others have demonstrated). When Angola’s civil war shed its Cold War allies after 1988 – the Battle of Cuito Cuanavale proved key to negotiating Namibia’s independence and the withdrawal of Cuban troops – it did not take long for Israel and the Angola’s MPLA-ruled state, once on opposite sides of the Cold War, to enter a warm embrace. Interest superseded ideology.

But first, Angola’s civil war had to incarnate another continental stereotype: resource war (a key step in the shift from Israel-South Africa-UNITA relations to Israel-MPLA relations).

In the early 1990s, UNITA controlled the diamond-producing regions of northeastern Angola, allowing it to purchase weapons on the international market. In 1993, a former South African Apartheid army officer, Fred Rindel, helped UNITA leader Jonas Savimbi establish diamond sales to a DeBeers subsidiary with offices in Antwerp and Tel Aviv. Meanwhile the Angolan state fattened the Angolan Armed Forces (FAA) on a rising tide of oil production. Between 1994-1999 – a period Angolans refer to as “neither peace nor war” – FAA and UNITA generals exchanged fuel for diamonds in a strange state of peaceable co-exploitation of the diamond rich Lundas region.

By 1999, the FAA drove UNITA troops from the region and the Angolan state began to take over the diamond trade. In 2000 Ascorp (Angola Selling Corporation), was afforded by the state a legal monopoly on diamond marketing. Aside from the Angolan state, Ascorp’s main stakeholders were TAIS of Belgium (first held by Isabel dos Santos, the daughter of the country’s President, then transferred to her mother) and Welox of Israel (part of the Leviev group).

Lev Leviev is an Israeli businessman. Born in Uzbekistan he resides in London. He is the world’s largest cutter and polisher of diamonds. He is Vladimir Putin’s friend. He owns key New York City properties. Among his holdings is Africa-Israel, a company with an investment profile in other mining ventures on the continent and in settlements on the West Bank (and a Times Square property apparently sold to Jared Kushner, Donald Trump’s son-in-law and confidant).

More official, less problematic relations pertain too. In late 2001 and early 2002, Israeli intelligence lent assistance to the FAA (then in hot pursuit of Savimbi). While official and public relations focused on greenhouse vegetables and the transfer of agricultural expertise, an Israeli drone cruised the skies of eastern Angola tracking UNITA troop movements and attempting to pinpoint Savimbi’s whereabouts. They eventually killed Savimbi in February 2002, ending 27 years of civil war by April of that year.

Meanwhile, in the Lundas, Ascorp tried to create a single buyer and seller for Angolan diamonds and thus abolish “blood diamonds.” In fact, it created a new kind of war. According to journalist Rafael Marques de Morais, Law 17/94 has turned the Lundas into a kind of reservation where the state confiscates anything from anyone or any enterprise, in the name of the public good, and delivers it to the mining companies. The local population is forced into mining and denied the possibility of producing a livelihood by agricultural means. Security services, owned and run by FAA generals, act with impunity. The terror in the area, as recounted in Morais’s book, Blood Diamonds: Corruption and Torture in Angola, is reminiscent of King Leopold’s red rubber regime in the Congo. Diamonds support a regime worse than that in Gaza, in an area larger than Portugal. Angolan generals profit. Israeli businessman Lev Leviev profits. And with profits from the alluvial miners of Lunda North and the industrialized mine at Catoca in Lunda Sul, together with companies like Alrosa, they’ve broken the DeBeers monopoly.

This is why, until recently, Israel has countenanced Angolan support for Palestine at the UN. Israeli prosperity matters more. But what work has that done for Angola? And what has changed with the recent vote? Angola recognized Palestine as a state and Yasser Arafat visited Angola regularly. In the 1980s, Angola’s radio jingle “From Luanda, Angola: the firm trench of the revolution in Africa!” keened a rallying cry to fight imperialism around the globe. Those connections weren’t just official. Angola’s ruling party, the MPLA, maintains a cog and machete on the nation’s flag (despite calls for change) and party protocol still finds cadres referring to one another as “comrade.” At the same time, ordinary Angolans strategically employ socialist rhetoric on their uber-capitalist rulers.

The connections between Israel and Angola operate in ambiguous historical terrain, no matter how glaring the profit of their current bond and its bind with justice. Subtending the new, friendly, lucrative relation is Angola’s socialist international and anti-imperialist past. Today the MPLA-ruled state cultivates symbols from that past to produce a sense of continuity and historical legacy. Some powerfully placed old-school cadres still believe in the right to self-determination and sovereignty. Political rhetoric and international relations mobilize this tension between old and new values. That’s what happened in the UN vote. This time Israel reacted, because it was the Security Council.

Angola got a slap on the hand. The Angolan ambassador to Israel got a parking ticket for parking illegally when he went to justify the vote to the Israeli Foreign Ministry in Jerusalem. And the Israeli press played up the charge of Angola as “occupying” the province of Cabinda; the latter “fighting for a sovereign independent state since 1960.” But it is hard to believe that this schoolyard, tit-for-tatting will bruise the moneyed networks that keep Angolan and Israeli elites unconcerned with righteousness.

*This post is adapted from Chapter 9, “Along the Edges of Comparison,” by Marissa Moorman in Jon Soske and Sean Jacobs (editors), Apartheid/Israel: The Politics of an Analogy (Haymarket 2015).

January 12, 2017

The Arabs had a country

Nasser with crowds. Image via Associated Press.

Nasser with crowds. Image via Associated Press.The death of Fidel Castro prompted some debate in the West. Many commentators concluded that the Cuban revolution’s descent into authoritarianism outweighed its contributions to the struggle for independence in Latin America and the Third World. Others have celebrated Castro as a hero of Third World liberation. For many in the West, it is puzzling to see the likes of Castro venerated as a hero. Perhaps the legacies of leaders such as Thomas Sankara, Hugo Chavez or Castro are only fully intelligible from a perspective that de-centers the West. From that perspective, victories – however flawed or fleeting – are cause for jubilation. Leadership like that of Castro’s broadened the horizon of political possibilities, and his internationalism and commitment to social revolution at home proved that revolution itself, however flawed, was indeed possible.

In the Arab world, there is no figure that embodies these ideals and contradictions than the second president of Egypt, Gamal Abdel Nasser. Himself a comrade of the late Castro, and leading figure of the non-aligned movement, Nasser counted among his sincere allies the likes of Malcolm X, Muhammad Ali, Che Guevera and Patrice Lumumba. He led the nationalization of the Suez Canal and subsequent confrontation with the British, French and Israeli militaries in 1956, which was not just an Egyptian or Arab victory, it was a victory for all colonized people, a reversal of one the glaring injustices of colonialism.

Nasserism became a dominant ideology in the Arab world, and inspired a wave of “republican” coups and revolutions; Jordan and Iraq in 1958, Yemen in 1962, Algeria in 1964, Sudan and Libya in 1969, Jordan again in 1970. Central to Nasserism, and the ideologically similar Baathism, was the impulse to reverse the dismemberment of the Arab world in the wake of the World War I through the eventual creation of a single pan-Arab state, “from the Ocean to Gulf.”

The most successful experiment in this proposed political union was between Egypt and Syria from 1958 to 1961. Political instability had wracked Syria since the current state was established as part of the Sykes-Picot agreement between colonial powers Britain and France in 1918. In 1958, the Syrian government proposed immediate unification with Egypt as a way to stabilize Syria and finalize a long-standing process of integration between the two states in pursuit of Arab unity. Though the unification was brief – undone in a coup led by Baathists in 1961 – it was welcomed with “overwhelming support” by the Arab masses, as Tareq Y. Ismael argued in his 1976 book, The Arab Left.

Even in death, Nasser was a man of his era. His passing in 1970 came as the Arab world was still reeling from the successful Israeli attack on Egypt in 1967, which was ultimately the death-knell of pan-Arabism and Nasserism. A Lebanese newspaper headline captured the significance of his death best, declaring: “One hundred million human beings – the Arabs – are orphans. There is nothing greater than this man who is gone, and nothing is greater than the gap he has left behind.”

Nasser’s successor, Anwar Sadat, worked diligently to undo much of the progress Egypt made under his predecessor’s reign, pivoting towards the West in foreign policy and initiating a painful economic liberalization that created the social and political conditions that caused the Arab revolutions of four decades later. Sadat’s agreement to forge a separate peace with Israel completed Egypt’s transition from the leader of the Arab world to a regional pariah. With the Arab world’s most powerful and populous country effectively removed from the Palestinian theater, the Arab states retreated inward and non-interference became the rule in their relations. Domestically, Sadat began the long process of neoliberal economic restructuring.

For some, the idea that Nasser’s image would be raised by Egyptian protesters in 2011 battling the very apparatus he built in Egypt, is a contradiction that cannot be resolved. Such a perspective fails to understand that Nasser is not remembered by most as a military dictator. Rather, he represents a bygone era in which principled opposition to a world system built upon and the exploitation of the Third World was a viable political project. Nasser, like Castro, like Chavez, like Sankara, symbolized the Third World’s dignified opposition to the very conditions that created it.

For Arab revolutionaries in 2016, that dignity remains elusive. The fall of Aleppo in Syria is but the latest in a series of crushing defeats. The euphoria of 2011 has given way to despair and tragedy almost everywhere in the region, and every concession to the revolution has been brutally rolled back. The ancien regimes have handled the challenge of 2011 more adeptly than anyone could have imagined.

In the Arab world, there is no other figure that embodies this counterrevolution more than the sixth president of Egypt, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi. His regime positioned itself as the continuation of the 2011 revolution, while stamping out any trace of it that remained. El-Sisi is attempting to coopt Nasser’s image in his propaganda, but he is nothing more than the farce to Nasser’s tragedy. Nasserism was legitimated by populist economic policy and anti-imperialism through pan-Arabism. El-Sisi can lay claim to none of these aspects of Nasser’s legacy. He has continued the process of neoliberal economic restructuring set forth by Sadat and acted as rear-gunner for Israeli colonialism on the ground, and most recently for incoming U.S. President Donald Trump at the UN Security Council.

It is perhaps in “the Arab sphere,” to use the parlance of Nasserism, that El-Sisi has most perfectly become Nasser’s inverse. His foreign adventures are a departure from the isolation of Sadat and Hosni Mubarak, but they have served the forces of counterrevolution at every turn. The Egyptian regime has entered the Libyan quagmire on the side of General Khalifa Haftar, who hopes to become “Libya’s Sisi”. Egypt was also an early member in Saudi Arabia’s war in Yemen, a familiar battlefield for Egyptian military, though in the 1960s, the Egyptians were going to war against the Saudis and their British backers.

But the reports of an Egyptian intervention in Syria to support the Baathist regime strike the most historic chord. Just as it was in 1958, Syria has become the epicenter of a crisis plaguing the wider Arab world, and Egypt, in the midst of its own political turmoil, is entering the fray. But where Nasser’s unification with Syria represented the hope that the Arab world could transcend the divisions it inherited from the colonial masters – the hope that a revolutionary moment could be exported – El-Sisi’s is the completion of Egypt’s counter-revolutionary turn. For Arabs leaders, it seems, there is only unity in betrayal.

January 11, 2017

“Doing good” in an age of parody

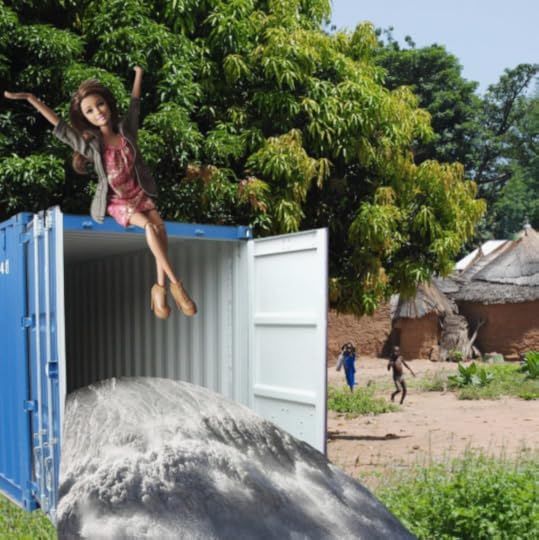

Image via Barbie Savior Instagram.

Image via Barbie Savior Instagram.For some time now it has felt overdone, even somewhat passé, to examine closely the ways that Africa is represented and how Americans engage with it. The backlash against clicktivism after #KONY2012 has bought us the funny ranging from Radi-Aid’s Band Aid-like music video calling on Africans to send radiators to freezing Norwegians, or the more recent viral White Savior Barbie Instagram account. Everybody is in on the joke. Does this mean there is little power left in the narratives about Africa that sites like Africa is a Country gave us such clarity about a few years back?

There are two reasons to take this moment of parody seriously. First it wouldn’t be far-fetched to argue that there is a dependence on parody as political critique. Second the “volunteer” or “saving Africa” industry parodied so bitingly on social media and elsewhere, continues to thrive sending thousands of young Americans and Europeans to Africa to do good. So, why does being in on the joke not slow down the desire to save Africans?

Much of how we think about volunteerism stems from the experiences of one of us (Elsa) working as a volunteer at the Moroccan Children’s Trust in Taroudant in southern Morocco close to Marrakesh. During her time there, Elsa interviewed volunteers from North America and Europe as well as on-site coordinators. (The research, by the way, was conducted for an honors thesis in International Comparative Studies at Duke University.) Instead of finding volunteers blind to the multiple and complex ways in which “voluntourism” can be a neocolonial project, the Moroccan Children’s Trust was supported by young volunteers fully aware of the relation between their work and parodies of it, as well as the cultural and political critique of the “white savior complex.”

What might appear to be a paradox – that young people volunteer for NGO’s abroad while aware of the critique of such work – is not only built on a long history of such debates in philanthropy but in its contemporary iteration, and is a logical outcome of neoliberal subject-making. Familiar images of Africa both presented in earnest or satirized continue to represent Africans as needing help. These allow a new generation to continue their self-development through service on the continent despite their awareness of the ethical problems. How does this happen?

The generation in the Global North that most consumes social media news and satire as politics has been labeled “millennials.” They are a generation born in Europe and North America between the early 1980s and the early 2000s, those who came of age at the beginning of the 21st century. They grew up in a geopolitical environment that values individual empowerment and asserts that compassion is the main catalyst for social change. Millennials have been raised to believe that they can and should be major actors in helping provide aid abroad. Their choices and desires are intertwined with the evolution of social media, which has helped create a collective society that empowers millennials to construct their own identities through being seen and recognized constantly. These selves are present not only on individual social media platforms but are effectively echoed in the way voluntourism and other forms of aid represent the role of young people in Africa. The circulation of images online between official sites created by international NGO’s and community based organizations and personal sites makes one’s own world almost indistinguishable from the global terrain of aid and development. As they have always done, such images also make consumers feel connected to a wider community, one united by shared global responsibility. These images are of course what Barbie Savior skewers. But they also successfully turn aid and philanthropy and volunteering into an entirely affective economy, switching emotional resonance for political and economic landscapes of inequality.

Millennials are also encountering an increasingly stressful and limited job market, albeit one that is meant to offer freedom and flexibility not available to their parents. They have experienced waves of financial collapse and economic downturns leading to higher levels of unemployment, student debt and lower levels of income than preceding generations had achieved at a similar age. They are, therefore, encouraged to pursue experiences that they can use to market themselves positively. Their job searches are characterized by employers’ desire for candidates with affective skills such as empathy and sympathy. Not only has the last decade seen significant increase in the professionalism and skills required of volunteers but volunteering is the ideal evidence of having achieved affective skills. Volunteering has therefore become a worthwhile investment for millennials in periods of economic stringency and despite increasing criticism.

Alongside this changing labor landscape, millennials have only really known a world characterized by neoliberal policies. They value above much else individual empowerment and are skeptical of a governments’ capacity to provide social good. Such subjectivity allows young millennials to understand their own voluntourism, not in terms of the unequal geopolitical relationships that they critique, but as an appropriate form for them to develop their own skills base, including something that could be called global empathy.

If, as neoliberal citizen-, their primary responsibility is towards their own advancement (because that is in itself a social good and globally responsible), there is no contradiction in being both critical of and a participant in voluntourism. Or being engaged in (or resistant to) many other seemingly paradoxical political and social movements.

January 10, 2017

The struggle for moral authority in Zimbabwe

Screenshot of Evan Mawarire’s This Flag Youtube video.

Screenshot of Evan Mawarire’s This Flag Youtube video.One of the most remarkable protest acts in Zimbabwe in 2016 was a little-publicized act by a small group of female Christian worshippers who dressed up in sacks, and prayed and wailed for three days. It was indicative of a year replete with seemingly symbolic and performative acts of defiance against President Robert Mugabe and the ruling party ZANU-PF’s chokehold on power.

In mid-2016, preacher Evan Mawarire started a campaign that startled the regime. Mawarire posted a video on Youtube of himself, swaddled in Zimbabwe’s national flag and lamenting the country’s state of affairs. Perhaps in spite of himself, he had gone straight to the heart of the beast. His words and actions appealed immediately to Zimbabweans’ moral sensibilities. Following Mawarire’s post, various other movements – mostly launched through social media – mustered courage and confronted the state using different tactics. Some organized saucepan-clanging marches, prayer meetings, dressed up in academic regalia and played street football or just sat, looking idle on the streets. The actions injured the ego of a regime that prides itself in ruling over one of Africa’s most educated populations; the message of “graduates,” in particular, was unequivocal: “We are graduates today, rovha mangwana ([and]loafers tomorrow).” These actions, while seemingly eschewing direct confrontation with a notoriously brutal state machinery, effectively challenged the moral authority of the regime. The last thing the Zimbabwe regime wants to surrender to anyone, even before the national airport, is its guardianship of the post-independence moral narratives and symbols and the authority that comes with them.

After independence from British colonial rule in 1980, Robert Mugabe moved swiftly to consolidate his hold on the political and historical landscape narratives and imaginations of the country. Monuments were built to commemorate fallen war combatants and civilians of the independence war. Besides Independence Day, other days were also set aside for commemoration of the war and its heroes. Particular care was taken in ensuring that the war narrative, national days and associated emblems, such as the national flag, were closely related to President Mugabe and the ruling party. It’s no exaggeration that Independence Day in Zimbabwe today is associated, not with a national embrace of a nation, and the journeys Zimbabweans have travelled together, but with the ruling party’s reaffirmation of its perceived one-sided heroism, moral hegemony and authority.

Mawarire prayerful lamentation and use of the national flag on Independence Day was a radical political action indeed: A flag sans the meanings attributed to it, we are reminded by social theorist Emile Durkheim, is just but a piece of cloth, but as a societal emblem, it is imbued with a moral force that galvanizes collective sentiments and exerts moral demands on individuals in society. His action hit the regime square in the face. The national outpouring and support that followed Mawarire’s Youtube post and his subsequent persecution, became for many not only a civic duty, but also a higher moral one. For the regime, it was an extreme challenge to its moral authority and the backlash was immediate. Mawarire had to skip the country into exile.

Prayer meetings, spontaneous possession by ancestral spirits in courtrooms during activists’ trials and other quasi-religious activities continued after he left. Such political actions do not lack historical precedence in Africa. In 1985, the anthropologist Jean Comaroff wrote about Apartheid South Africa – and how the use of brute force in suppressing political protests gave rise to symbolic and performative practices, often involving ritual practice, in place of “open discourse.” In her analysis, Black Africans’ religious communities took centre stage in defying the brutal Apartheid machinery. Similarly, in the Zimbabwean case where any kind of dissent is met with booted feet, gunfire, water cannons and tear gas canisters, creative modalities of political action, such as the manipulation of religious and cultural codes, are common responses from the oppressed. During the country’s liberation struggle against white minority rule in the 1970s, it was not uncommon for Black guerilla armies of ZANU and ZAPU to seek spiritual endorsement from traditional chiefs and spirit mediums. Over and above their Marxist “revolutionary” training, ZANU fighters often sought legitimacy from mediums of the spirit of Mbuya Nehanda, a female ancestor claimed by many Shona-speaking groups in the country. So, political efforts that lean on things religious and spiritual have today also become useful in shaking the edifice of dictatorship. In fact, they are more useful than the calculated ten-point, calibrated plans and “organic” political actions of those identifying as “secular” political outfits. It is pastoral figures, and other religio-political actors who have shown a knack at articulating the social experiences of Zimbabweans, and they have a redemptive appeal to the long-suffering nation.

What does this mean then for the future of political organizing and mobilization in Zimbabwe? Clearly, modalities of mainstream struggle also have to change or accommodate other creative political actions, even when they appear transient. It’s no longer helpful to cast aspersions on those who don’t bring forward political manifestos or chant revolutionary slogans. Religious, moral and psychic solidarities are not compensatory to “real” political action. They are real, and they reflect sentiments rooted in extant conditions of social existence. In Zimbabwe people have turned en masse in recent years towards religion – be it charismatic churches, traditional revivalist movements or other spiritual groups. Civil society movements, such as those of organized labor and students (the traditional constituencies of opposition parties) have been largely decimated during the last two decades. So, religion, taken here in the broader sense as a rallying point for the collective social organization and action, has gained more from the crisis. And it is religion that will have the most significant role in either delaying or inspiring future meaningful political action in Zimbabwe.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers