T.C. Moore's Blog

July 22, 2024

Moravians: Theological Trailblazers, Part 2 – Jesus & Scripture

Cookbook Theology

Cookbook TheologyMany (perhaps most) Christian denominations, especially those that identify as “Protestant”, consider themselves “Jesus-centered.” They may claim this, but when the rubber meets the road, they often reflexively default to a generic and defensive form of Biblicism that isn’t Jesus-centered at all. For example, some Christian denominations support highly controversial and harmful doctrinal positions and policies regarding ordination and marriage by exclusively citing passages from the Hebrew Bible and the letters of Paul. Jesus’s life, ministry, teaching, example, death, and resurrection aren’t the foundation of their theology. Rather, they consult the Bible like it’s a cookbook: Turn to any page and all the recipes are equally applicable. How odd, considering these same traditions disregard commands from the Hebrew Bible on a whole host of subjects ranging from dietary restrictions to farming prohibitions to child-rearing. These denominations don’t require their members to follow laws regarding Kosher eating. Those, they conclude, have been conveniently done away with by the New Testament. Yet the laws these denominations pick from the Hebrew Bible like options in a buffet are the laws that reinforce their preconceived positions on human sexuality, which can be employed as a bludgeon against those they perceive to be “sinners.” This is hermeneutical malpractice.

Essentials vs. MinisterialsFrom our fraught history, Moravians understand that the Bible can be used as a weapon against those with less power by those with greater power. After the bloody Hussite Wars and merciless persecution, the ancient Unity knew that contentious divisions that produce destructive violence was not what Christ wants for his church. They also knew that at any moment those in power could imprison their ministers, seize their places of worship, and burn their sacred books. They also knew that some holy things, like scripture itself, could be used against them as weapons, as it was in the inquisitions. This is why Luke of Prague refined the Unity’s thinking around “essential” matters of faith by clearly distinguishing them from “ministerials.” By creating this second category and placing highly important things like scripture, the church, sacraments, the priesthood, and even doctrine in this category, the Unity distinguished itself from all other Christian traditions. Early Siblings (also called “Brethren”) like Luke were convinced that as good as these things were, they are “sacred tools given by Christ and the Holy Spirit to lead us to what is essential. They are sacred not in and of themselves, but because of the essential things to which they lead and direct us.” 1

Tools aren’t unimportant; ask a specialist of just about any craft. Tools are extremely important! But the brush of a painter isn’t the painting. Neither is the chisel in the same category as the sculpture. As prized and indeed cherished as they are, tools are meant to facilitate expression, formation, production. “Ministerials” are so called because they serve, they facilitate, the process by which one experiences Creator, Redeemer, Sanctifier; Faith, Love, and Hope. As vital as scripture is, scripture used improperly is not sacred, but desecrated. As powerful as they can be, the sacraments when used to divide or oppress human beings are no longer holy.

The Chief MinisterialMoravians honor scripture as the “chief ministerial.” This means scripture is the standard we use to evaluate our doctrine and practice. However, it also prevents the scriptures from being worshiped as in the bibliolatry of Biblicism. The Ground of the Unity, one of the most important statements of Moravian faith says,

The Triune God as revealed in the Holy Scripture of the Old and New Testaments is the only source of our life and salvation; and this Scripture is the sole standard of the doctrine and faith of the Unitas Fratrum and therefore shapes our life.”

It is God, not the Bible, who is the source of our life and salvation. The Bible is a sacred tool that God uses, but it is not God. “The Moravian Church recognizes that Scripture is the witness to faith in God rather than the source of faith.” 2 This means that we must decide how to interpret the Bible in a way that comports with our allegiance to Jesus Christ.

Christocentric Hermeneutic

Christocentric HermeneuticSince the formation of the ancient Unity, the Moravian tradition has been upfront about our Jesus-centered hermeneutic. The early Siblings prioritized the New Testament and particularly Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount in their discernment of how to live out their faith. In more recent times, in North America in particular, the affirmation of LGBTQ+ siblings in Christ has raised hermeneutical questions afresh. Will the Moravian Church continue its tradition of Christ-centered interpretation, or cave in to the peer pressure of Biblicism? To meet this question, Moravian theologians and pastoral leaders joined together to draft “Guiding Principles of Biblical Interpretation in a Moravian Context.” 3 Through scholarship and dialogue, the statement thoroughly explores the history and theology of the Unitas Fratrum. Among its conclusions is this:

…as Moravians… we do not believe that Jesus points us to Scripture so that we can find the answers there, but rather that Scripture points us to Jesus so that we can find the answers in him. As a church we must be attentive to God’s Word (the word of the cross, the word of reconciliation, the word of personal union with the Savior, the word of love between one another), and our faith and order must be formulated under Scripture and the Holy Spirit. Yet, it is not Scripture and our conformity to a particular interpretation of it that unites us, but rather Christ, our Chief Elder, who holds us together by keeping us all close to Him.”

At a gathering at New Philadelphia Moravian Church in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, on January 19th, 2016, Pastor Worth Green share about his own journey of understanding the hermeneutical and pastoral complexities of interpretation the Bible’s teaching around sexuality, and the affirmation of same-sex unions in particular. In his presentation (linked to below) he shared about a conversation he had with his 90+ year old father, who expressed that he must oppose same-sex marriage on the grounds that it is prohibited in the Bible. Pastor Green asked his father about the Bible’s command to stone disobedient children (e.g. Deuteronomy 21:18–21). Pastor Green asked his father, “Is this the word of God for us today?” His father responded, “My spirit will not accept it and it does not measure up to Jesus Christ.” Pastor Green commented, “Wow, what a Moravian answer.”

The Moravian Church doesn’t just say it is Jesus-centered—it proves it by how it categorizes and interprets the Bible.

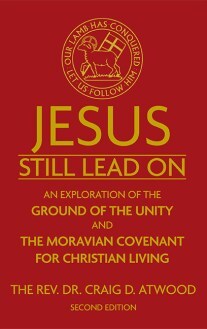

Craig Atwood, “In Essentials, Unity: Understanding the Essential Things” The Moravian Magazine, Jan/Feb 2014, quoted in The Moravian Catechism (IBOC, 2020), p.25.Craig Atwood, Jesus Still Lead On: An Exploration of the Ground of the Unity and The Moravian Covenant for Christian Living, Second Edition (The Interprovincial Board of Communication, Moravian Church in America, 2023), p.111.For more on this, see the Full Program of the Moravian Interpretation of the Bible conference and the document it produced:https://youtu.be/sa4O8_ub9rw?si=ivQ0RrUH5E4gWXcf https://www.trinitymoravian.org/download/Guiding-Principles-Handout.pdf

July 8, 2024

Moravians: Theological Trailblazers, Part 1 – Forged in Fire

This week I’ve been reading Jesus Still Lead On (Second Edition) by Dr. Craig Atwood. It’s a book written to help people better understand two statements of faith that are important to Moravians: “The Moravian Covenant for Christian Living” and “The Ground of the Unity.” As I’ve been reading, I’ve been struck once again by just how many foundational teachings of the Moravian tradition are seminal for all Protestant Christians. It’s surprising how this relatively obscure movement of Jesus-followers has had such an outsized impact on global Christianity—and it may be largely due to its unique history.

This week I’ve been reading Jesus Still Lead On (Second Edition) by Dr. Craig Atwood. It’s a book written to help people better understand two statements of faith that are important to Moravians: “The Moravian Covenant for Christian Living” and “The Ground of the Unity.” As I’ve been reading, I’ve been struck once again by just how many foundational teachings of the Moravian tradition are seminal for all Protestant Christians. It’s surprising how this relatively obscure movement of Jesus-followers has had such an outsized impact on global Christianity—and it may be largely due to its unique history.

Moravian theology is borne of their rich yet repressed history that begins as a reform movement within the medieval Western church but grows into an independent and illegal ministry. After intense persecution, it is later reborn as a conglomerate of religious refugees seeking to recover an embattled heritage. This historical and geographical journey that spans centuries and the globe—at times in the wilderness of political and religious persecution, and at other times in danger of utter annihilation—has forged the theological imagination of this innovative and pioneering denomination.

Jan Hus (1372–1415) burned at the stake during the Council of Constance1. The Ancient Unity

Jan Hus (1372–1415) burned at the stake during the Council of Constance1. The Ancient UnityThere are three major eras of the Moravian theological tradition. The first is after the martyrdom of Jan Hus, a beloved Bohemian Catholic priest and professor who was inspired by Wycliffe to challenge and reform the Western Church in areas of corruption and other harmful practices. After he was burned at the stake for his audacity, the Hussite Wars engulfed Bohemia and Moravia, leading to massive ecclesial shifts, including the birth of the Unitas Fratrum, the first “Protestant” church.

This first major era is called “the ancient Unity”, the original ministry that liberated itself from the domination of the medieval Western church, which began in a small village called Kunvald in Bohemia in 1457 and was almost entirely lost by the 1620s. The Unity was the first free church, the first peace church, and the first “Protestant” church. It also pioneered ecumenical work and innovated sacramental theology as well as soteriology.

Count Nicholas Ludwig von Zinzendorf (1700–1760)2. The Renewed Moravian Church

Count Nicholas Ludwig von Zinzendorf (1700–1760)2. The Renewed Moravian ChurchOne of the most prominent figures in Moravian history, John Amos Comenius, prophetically dreamed that the Unity would become a ‘hidden seed’ that would be born again. His dream came true in the second major era, the “Renewed Moravian Church,” that was reborn in Herrnhut, Saxony, in 1722, on the estate of Count Nicholas Ludwig von Zinzendorf, a charismatic, innovative, and ecumenical Lutheran Pietist. There at Herrnhut, Zinzendorf was instrumental in uniting a diverse community of Jesus-disciples from multiple cultures and traditions. This period was filled with innovations in missions, music, and ministry that would go on to shape global Protestantism ever since.

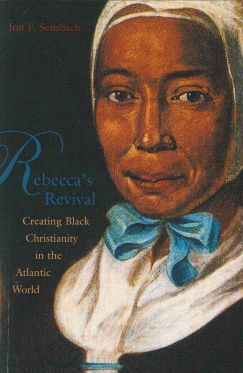

Rebecca Protten “Mother of Modern Missions” (1718–1780)3. The Reorganized Moravian Church

Rebecca Protten “Mother of Modern Missions” (1718–1780)3. The Reorganized Moravian ChurchThe third major era of Moravian history began in 1857 when the global Moravian Church reorganized itself into autonomous provinces joined together in one “Unity.” This decentralized the church from Western/American power. This work continues and we may be part of a new, fourth era since 1957: a Post-Colonial Era.

Perhaps due to its early and intense conflict with powerful religious and political institutions, Moravian theology has been developed in the midst of necessity and in response to extreme danger. This tempers its approach to theology like steel. Moravian theology is not only time-tested, but battle-hardened. Many of the theological innovations Moravians pioneered have thus seeded other traditions forming the basis upon which they have developed further. Often without proper recognition, Moravianism has been seminal in many forms of Reformation/Protestant theology.

While it would be impossible to exhaustively cover all the ways Moravians have been theological trailblazers, over the next several posts I only want to highlight a few that are most meaningful to me:

Jesus & ScriptureSacraments & SoteriologyEcclesiology & EcumenismDiscipleship & MissionsEducation & ScienceGender & SexualityOrthopraxy & OrthodoxyTune in next time!

Moravians: Theological Trailblazers, Part 1

This week I’ve been reading Jesus Still Lead On (Second Edition) by Dr. Craig Atwood. It’s a book written to help people better understand two statements of faith that are important to Moravians: “The Moravian Covenant for Christian Living” and “The Ground of the Unity.” As I’ve been reading, I’ve been struck once again by just how many foundational teachings of the Moravian tradition are seminal for all Protestant Christians. It’s surprising how this relatively obscure movement of Jesus-followers has had such an outsized impact on global Christianity—and it may be largely due to its unique history.

This week I’ve been reading Jesus Still Lead On (Second Edition) by Dr. Craig Atwood. It’s a book written to help people better understand two statements of faith that are important to Moravians: “The Moravian Covenant for Christian Living” and “The Ground of the Unity.” As I’ve been reading, I’ve been struck once again by just how many foundational teachings of the Moravian tradition are seminal for all Protestant Christians. It’s surprising how this relatively obscure movement of Jesus-followers has had such an outsized impact on global Christianity—and it may be largely due to its unique history.

Moravian theology is borne of their rich yet repressed history that begins as a reform movement within the medieval Western church but grows into an independent and illegal ministry. After intense persecution, it is later reborn as a conglomerate of religious refugees seeking to recover an embattled heritage. This historical and geographical journey that spans centuries and the globe—at times in the wilderness of political and religious persecution, and at other times in danger of utter annihilation—has forged the theological imagination of this innovative and pioneering denomination.

Jan Hus (1372–1415) burned at the stake during the Council of Constance1. The Ancient Unity

Jan Hus (1372–1415) burned at the stake during the Council of Constance1. The Ancient UnityThere are three major eras of the Moravian theological tradition. The first is after the martyrdom of Jan Hus, a beloved Bohemian Catholic priest and professor who was inspired by Wycliffe to challenge and reform the Western Church in areas of corruption and other harmful practices. After he was burned at the stake for his audacity, the Hussite Wars engulfed Bohemia and Moravia, leading to massive ecclesial shifts, including the birth of the Unitas Fratrum, the first “Protestant” church.

This first major era is called “the ancient Unity”, the original ministry that liberated itself from the domination of the medieval Western church, which began in a small village called Kunvald in Bohemia in 1457 and was almost entirely lost by the 1620s. The Unity was the first free church, the first peace church, and the first “Protestant” church. It also pioneered ecumenical work and innovated sacramental theology as well as soteriology.

Count Nicholas Ludwig von Zinzendorf (1700–1760)2. The Renewed Moravian Church

Count Nicholas Ludwig von Zinzendorf (1700–1760)2. The Renewed Moravian ChurchOne of the most prominent figures in Moravian history, John Amos Comenius, prophetically dreamed that the Unity would become a ‘hidden seed’ that would be born again. His dream came true in the second major era, the “Renewed Moravian Church,” that was reborn in Herrnhut, Saxony, in 1722, on the estate of Count Nicholas Ludwig von Zinzendorf, a charismatic, innovative, and ecumenical Lutheran Pietist. There at Herrnhut, Zinzendorf was instrumental in uniting a diverse community of Jesus-disciples from multiple cultures and traditions. This period was filled with innovations in missions, music, and ministry that would go on to shape global Protestantism ever since.

Rebecca Protten “Mother of Modern Missions” (1718–1780)3. The Reorganized Moravian Church

Rebecca Protten “Mother of Modern Missions” (1718–1780)3. The Reorganized Moravian ChurchThe third major era of Moravian history began in 1857 when the global Moravian Church reorganized itself into autonomous provinces joined together in one “Unity.” This decentralized the church from Western/American power. This work continues and we may be part of a new, fourth era since 1957: a Post-Colonial Era.

Perhaps due to its early and intense conflict with powerful religious and political institutions, Moravian theology has been developed in the midst of necessity and in response to extreme danger. This tempers its approach to theology like steel. Moravian theology is not only time-tested, but battle-hardened. Many of the theological innovations Moravians pioneered have thus seeded other traditions forming the basis upon which they have developed further. Often without proper recognition, Moravianism has been seminal in many forms of Reformation/Protestant theology.

While it would be impossible to exhaustively cover all the ways Moravians have been theological trailblazers, over the next several posts I only want to highlight a few that are most meaningful to me:

Jesus & ScriptureSacraments & SoteriologyEcclesiology & EcumenismDiscipleship & MissionsEducation & ScienceGender & SexualityOrthopraxy & OrthodoxyTune in next time!

April 7, 2024

No Substitute for Cruciformity: A Review of Lamb of the Free by Andrew Rillera

Ask your average American Christian about the meaning of Jesus’s cross, why he died and what it accomplished, and you’re likely to hear some version of an atonement theory known as “Penal Substitution” or “PSA”. (There are complex socio-cultural and historical reasons for this, but that isn’t my focus here.) This PSA explanation can be expressed in a variety of ways, but some of the core components are that Jesus died in our place suffering the penalty of sin that we deserved so that we don’t have to. The “wrath of God” is also often suggested as a reason for the need for blood. Whether warranted or not, PSA is associated with the ancient Israelite sacrificial system detailed most extensively in the book of Leviticus. Someone might elaborate on their explanation by saying something like, “In the Old Testament, a lamb had to be killed instead of a person, for God to forgive their sins.” This is taken to be the biblical background for the cross: Jesus is the lamb of God who had to be killed instead of humanity so that God could forgive sins.

No doubt someone will say this as an unfair caricature. But I’ve heard this kind of explanation more times than I can count in my over two decades of pastoral ministry. Whether it represents the best presentation its most scholarly proponents would offer is another matter altogether. Laypeople can’t be held to the same standard as biblical scholars, and it’s important to be honest about what people retain from our presentations. There are even much more profane examples I can personally cite. For example, I once attended a Christmas service at a megachurch outside Los Angeles in which the pastor said, “I love you all a lot, but I don’t love you enough to kill my only son for you! That’s how much God’s loves you!” Imagine thinking that makes God seem loving.

Not only does the PSA explanation of the cross portray God as wrathful and violent, it also portrays Jesus as doing something for us that we don’t have to. I’ve witnessed people well up with tears talking about how grateful they are that they don’t have to die for their sins, because Jesus died instead of them. It’s closely related to way many Christians reverence Jesus as their Savior, but don’t feel obligated to obey his teachings as their Lord. It’s much easier to think of Jesus as a historical sacrifice for sins and a distant divine person than it is to embrace Jesus’s Way of the Cross as one’s own.

That’s why Andrew Rillera wrote Lamb of the Free: Recovering the Varied Sacrificial Understanding of Jesus’s Death.

Disambiguating SacrificeAs a former college ministry pastor and now an undergraduate professor, I have seen first- and secondhand how much destruction is caused by Christians because their essentialized substitutionary framework prevents them from even wanting to be conformed and transformed into the cruciform image of Christ. Substitutionary frameworks—whether intentionally or not—corrode the logic of Christian discipleship among everyday Christians. Substitution makes conformity to the cruciform image of Christ incoherent. If Jesus is my substitute, why do I need to take up a cross? Why do I need to have fellowship with his sufferings? Why do I need to be co-crucified?” (p.8)

Before Rillera can get to the positive vision of the cross he wants to present, he has a lot of ground-clearing to do. American Christians often have very little knowledge of the Israelite sacrificial system, yet many think they know what it entails. Rillera demonstrates that much of what is typically thought to be included are distortions and conflations. For example, it might come as a shock to some Christians to learn that not all sacrifices served an “atoning” function. “It is all too common to think that there is only one purpose for Levitical sacrifice; namely, to atone. However, not all sacrifices have an atoning function. […]there are two main categories for sacrifices broadly speaking: these are ‘the categories of gift-offering-display and/or pollution removal.’ ” (p.28) To drive home this point, the sacrifice most associated with Jesus’s cross, the Passover, is a “well-being” sacrifice, Not an atoning sacrifice.

Conveniently, it is straightforward to recognize if a sacrifice is atoning or non-atoning: if the laity eat from it, then it cannot be an atoning sacrifice. This is how we know, for example, that the Passover is a type of communal well-being sacrifice since it is eaten by the laity. This is why these sacrifices are sometimes translated as ‘fellowship’ or ‘communion’ offerings, since these are a way for the worshiper to commune or have fellowship with God at the sanctuary.” (p.29)

Furthermore, sacrifices that did function as atoning, didn’t atone for moral sins (like the kind that required a death sentence), they purified or decontaminated sacred spaces or objects for God’s presence. Further still, the offering of animals as sacrifice wasn’t about their suffering or death in the place of human beings. Instead, ritual sacrifice performed in the prescribed manner transformed the killing into an offering and the animal’s death into a sacred gift.

Rillera systemically walks readers through a detailed survey of the Levitical sacrificial system to disambiguate “sacrifice” from “killing” and “atonement.” These things are Not synonymous. After that, Rillera differentiates the kinds of sins for which atoning sacrifices could purify or decontaminate and the kinds of sins they could not. The prophets didn’t condemn Israel for ritual impurity; they condemned Israel for moral sins like idolatry and injustice. These are the sins that remained unforgiven—the sins for which Jesus died.

No Substitute for CruciformityUltimately, Rillera’s aim is to remind Christians that Jesus’s death isn’t merely a historical event we can point to and be grateful for. No, Jesus calls his disciples to follow him in the Way of the cross, a cross-shaped life. Christian discipleship isn’t a ‘spectator sport’; every disciple is called to participate in the self-giving love Jesus modeled for us on the cross.

Jesus’s death is a participatory phenomenon; it is something all are called to share in experientially. The logic is not: Jesus died so we don’t have to. Rather it is: Jesus died so that we, together, can follow in his steps and die with him and like him, having full fellowship with his sufferings so that we might share in the likeness of his resurrection. […] In short, while Jesus did die for us, this does not mean that Jesus died instead of us. It means that he died ahead of and with us.” (p.7)

This is why we don’t just watch a priest or pastor receive communion on our behalf, but we partake ourselves. This is why the famous hymn in Philippians 2 isn’t about Jesus being humble so that we don’t have to be. No, the apostles teach us that Jesus’s cross is ours too. “To this you were called, because Christ suffered for you, leaving you an example, that you should follow in his steps.” (1 Peter 2:21) The apostle Paul even says that his own suffering for the sake of the Gospel is a continuation of Christ’s sufferings (Col. 1:24–29). Cruciformity isn’t an optional part of the Christian life; it is the Christian life.

That is why I’d highly recommend this work to all those who are seeking a better explanation for Jesus’s death on the cross. Rillera’s work deserves a wide reading, even if it is primarily geared toward a more academic audience. If lay readers are interested, I’d suggest reading it with seminary-trained clergy. There is a far amount of technical language. But the benefits of this study shouldn’t be confined to those with a working knowledge of Greek or Hebrew. This book has the potential to infuse Christians with a renewed passion for the Way of the Cross.

January 12, 2024

The Book of Clarence: Some Initial Thoughts

It’s late and I just got home from seeing The Book of Clarence in the theater and I have no intention of writing a thorough review. But, I did want to document some initial impressions while they’re still fresh on my mind. Fair warning: these are hot off the press and may contain “spoilers”.

1. The Book of Clarence is NOT About JesusGo back and read the title of the movie again. This is not the Book of Matthew, Mark, Luke, or John. This is a film about an “Everyman”. Clarence is meant to represent a regular person who could have lived at the time of Jesus in Jesus’s general vicinity. It’s a story about someone who is layered, flawed, but has great potential (like all of us!) It’s a story about doubt, faith, love, greed, regret, sibling rivalry, and growth as a person. This is not an evangelistic tract about how to become a follower of Jesus (but it also might make some more curious!) If you’re looking for a story centered around Jesus, read the Gospels, or watch The Chosen, or wait until Martin Scorsese comes out with his film on Jesus next year. This isn’t that movie.

2. The Book of Clarence Honors JesusI’ve seen a lot of comments decrying this film as blasphemous based solely on the trailers. But one shouldn’t judge a film by its trailers (even though I saw no blasphemy in the trailers either!) Now that I’ve seen the film—and I’m a pastor and a devout follower of Jesus—I can assure you The Book of Clarence isn’t blasphemous at all. If anything, the film goes out of its way to reverence Jesus. Jesus is depicted as the Son of God, divine, a miracle-worker, beloved by the people, a prophet, a threat to Rome, a defender of the defenseless, and the Messiah. It doesn’t get any less blasphemous than that!

I can’t help but think the reason some people might be pre-judging this film as blasphemous is solely because the role of Jesus is played by a Black man. But if one has even a cursory understanding of the ancient Near Eastern cultural and historical context of the New Testament, they would know that it’s far more accurate for a person of African descent to play Jesus than a person of European descent. And there have already been way too many European Jesuses on film!

3. The Book of Clarence is EntertainmentIn the middle of this film where people are walking around first-century Jerusalem in sandals and tunics there’s a fun dance sequence set to Nights Over Egypt by The Jones Girls. If that doesn’t signal to audiences that this film is meant to be entertaining, we aren’t paying attention. There are also many surrealist and absurdist elements throughout the film. People float in the air when they smoke “herbs”, lightbulbs appear over Clarence’s head when he has an idea, among other things. Again, this tells audiences: relax, this is fun. After all, this movie is a comedy people! So, if you’re looking for a somber, historical, dramatic depiction of first-century life in Judea-Palestine, this isn’t the film for you. But if you’re looking for an entertaining yet thought-provoking comedy set in New Testament times, then you will likely really enjoy this movie.

4. The Book of Clarence Has a Lot of HeartWhile there were several distracting plot holes, overall I found the film really touching. It likely won’t earn an Oscar, but I thought he did a very good job. His performance was heart-felt and, at times, really moving. He wrestles with a full range of human emotions and experiences, from unrequited love, to the need for recognition, to compassion for the oppressed. And ultimately, he doesn’t become some perfect person; he simply grows as a person (which is one of the main themes of the film). I really liked Clarence’s relationship with his mother. I really liked the way the film depicted racism. And I really liked how the film depicted John the Baptizer and Jesus’s disciples. Is the film perfect? Of course not! But no film is.

Go see The Book of Clarence!December 31, 2023

Top 5 Books of 2023

This year I took a course in Moravian history online through Moravian Seminary in Bethlehem, PA with the esteemed historian, Dr. Craig Atwood. That course required reading several textbooks. Plus, I did a lot of research in the Moravian archives with primary sources for a research paper. But, somehow, I did get a chance to do some leisure reading, though not nearly as much as I would have liked. Here are the top five books I read for fun this year:

Humility Illuminated by Dennis Edwards

Humility Illuminated by Dennis EdwardsThere’s no one I know who I’d trust more to write a book-length treatment of humility from a Christian perspective than Dennis Edwards, and he doesn’t disappoint. Humility Illuminated not only addresses the common twin errors of false humility masquerading as humility and humility as a strategy to success. It also addresses the socio-political dimension of humility. Often when Scripture is addressing humility, it’s addressing injustice. Dennis calls direct attention to it and I loved every paragraph. During our Advent series at Roots, I preached a sermon called “Making Room for Humility” where I drew heavily from this book. This is a must-read!

Ecosystems of Jubilee by José Humphreys and Adam Gustine

Ecosystems of Jubilee by José Humphreys and Adam GustineAnother one of my personal friends and mentors, José Humphreys also wrote a book this year, with a co-author, Adam Gustine. This book is fantastic at clearly laying out the economic vision of the Hebrew Bible and New Testament and how they relate to the modern world. So often Christians, particularly Americans, have deeply distorted views on Jesus’s vision for economic justice. This book is essential for all those who question things like “debt forgiveness” or who think the parable of the talents is somehow an endorsement of Capitalism. I highly recommend this one!

When Everything is On Fire by Brian Zahnd

When Everything is On Fire by Brian ZahndZahnd’s book always minister to me. I’ve read several of them and they’re all very well-written. I’m always struck by how seamlessly (and seemingly effortlessly) Zahnd is able to weave together the work of great poets, musicians, philosophers, Scripture, and his own life’s journey. He’s extremely well-read and has a grasp of literature and philosophy that is almost singular among popular pastoral authors. This book walks readers through the present crisis of faith in the West. A lot of people have been talking about “deconstruction” but Zahnd’s take is far more sophisticated. And I love that his book concludes with some solid chapters on contemplative practices, something I’ve learned a lot about from him. Highly recommend.

Godbreathed by Zach Hunt

Godbreathed by Zach HuntGodbreathed is Zach Hunt’s foray into the well-trod territory of books that poke holes in Fundamentalist hermeneutics and the misguided doctrine of inerrancy. If you’re not already familiar with these works or the subject in general, this book might challenge you and surprise you. But if you’ve at all read other works in this vein, there wasn’t a lot of new insights. Instead, the strength of this book was Hunt’s casual and funny writing style. The book is written almost as if you’re having a beer with Zach and for some readers that will be enough to make it worth reading. I really enjoyed it.

Mirror for the Soul by Alice Fryling

Mirror for the Soul by Alice FrylingOver the summer at Roots, we preached through a series on how the Enneagram could be a tool that helps us find rest for our souls. For that series, I read several books and articles about the Enneagram, but this one stood out. It wasn’t exactly comprehensive, but it was a solid introduction for anyone generally familiar but not well-versed in the language and concepts of the Enneagram. Fryling’s writing style is highly accessible and at times vulnerable. If you’re at all interesting in learning more about the Enneagram, I’d say this book is a great place to start.

December 24, 2023

Jesus is Good, Not Monarchy

The Advent season—with its royal purple liturgical color and symbols of kingship—has inspired Peter Leithart to write a brief and baffling reflection on authority for First Things. Leithart’s Advent article is entitled “Monarchy is Good.”

The flow of his argument goes like this:

At Advent time, we celebrate Jesus as King. But Americans don’t like authority, which is silly. Americans are like petulant children, complaining that grown-ups are mean. Don’t Americans know that Jesus redefines what it means to be a king and models a different kind of authority—authority that empowers others? Sure, some authority figures use their authority in not-so-good ways. But, because Jesus is a King, authority is good: “Monarchy is good.” QED?

This line of argumentation is almost entirely wrong-headed. The only things Leithart gets right here are: Advent entails honoring Jesus as King and Jesus redefines “kingship.” The rest is a foil he uses to prop up conservative culture war talking points. This article is less about sharing the Gospel of Jesus than it is about taking potshots at progressives and propping up conservative positions with flimsy thinking.

Consider this crucial passage:

Part of the problem is that we’ve been catechized to regard all forms of authority as oppressive. Our world has lost the distinction between authority and authoritarian and blurred the difference between use and abuse. Fathers rule their homes—patriarchal tyranny! Parents correct or spank their kids—child abuse! Pastors discipline unruly members—pastoral exploitation! Want severe punishments for murderers and rapists? You’re a Nazi or a Fascist.”

Let’s break this down. Leithart asserts that the world has catechized people to regard all forms of authority as oppressive. Really? Everyone? Or, is this an obvious Straw Man?

Is Fatherly “Rule” Really Unquestionable?The first authoritative relationship Leithart points to is “Fathers rul[ing] their homes.” I’m sorry, what? Since when are fathers “rulers”? This isn’t a description of default fatherly authority; this is a highly disputed interpretation. I’m a father, and a Christian, and I don’t have any intention of “ruling” my home. My discipleship to Jesus won’t allow me to assume such an arrogant posture. Not to mention, what would that say about my spouse, the mother of my children? Is she “ruled” over by me as well? This is nothing less than a highly presumptuous and unsubstantiated Complementarian position.

What response does Leithart put in the mouths of those “catechized to regard all forms of authority as oppressive”? He ascribes to them the response: “patriarchal tyranny!” (With an exclamation point for emphasis) But I want to ask: Are Leithart’s imaginary interlocutors wrong though?

Leithart has undeservedly given the father (and only the father) in this hypothetical scenario the power to “rule.” Is there another term for male-only rule besides Patriarchy that I’m unaware of? No? Well, then, yes, it is patriarchal—by definition. It’s not enough that Leithart doesn’t like the label—it’s accurate. Father-only rule is called Patriarchy. “Facts don’t care about your feelings.” But what of “tyranny”? Does this hypothetical father “rule” with a council of elders? Does his rule include a Parliamentary system? Or, is he the sole, unchecked “ruler”? Is tyranny no longer an accurate description of a single unchecked ruler? The American Declaration of Independence seems to think tyranny is the correct descriptor for such “rule” and I don’t disagree.

Is Spanking Really Unquestionable?The next authoritative relationship Leithart points to is that of parents to their children. Specifically, he points to the parents’ authority to “correct or spank their kids.” This is thinly-veiled sleight of hand. Virtually no one questions whether parents have authority to “correct” their kids. But Leithart sneaks in a second word: spank. He’s not slick. He knows spanking is a highly contentious subject, so he couples it with “correct,” which is too vague to raise anyone’s hackles. But these two words aren’t synonymous at all. Parents can “correct” their children in any number of ways that doesn’t involve physical force or violence. But, to smuggle violence into the “authority” he’s advocating, he couples correction with corporal punishment.

When my spouse and I began parenting our children, we weren’t well-educated about child development. And, we didn’t come from families of origin that modeled for us healthy forms of correction. So, we defaulted to spanking as a form of discipline. It was awful and we deeply regretted it. Of course, we defended it while we were utilizing it. At the time, we felt like we had to. But, the more we learned about trauma, about brain development, about social-emotional development, the less wise or healthy we found spanking.

According to Leithart this makes us one of his hypothetical authority-haters. But we aren’t. We still believe that as parents we serve in a vital role of authority for our children. And we still expect respect and administer discipline. But, we would never promote physical violence as a form of “correction.” Our discipleship to Jesus has taught us to seek nonviolent means of resolving conflict and to model self-giving love. (But I’m getting ahead of myself. More on Jesus’s “authority” later). Leithart would have readers believe that spanking is just good ol’ fashioned “correction” that only authority-haters object to. But, what if violently hitting children actually is abuse? Is that not a possibility?

Is Deciding Which Church-members are “Unruly” Really Unquestionable?From parents, Leithart moves on to the authority of pastors in the local church. Specifically, he homes in on their authority to administer church discipline. It should be noted here that there may be at least as many perspectives on church discipline as there are Christian denominations. Is Leithart so certain all the editorial staff of First Things agree on this matter? I doubt it.

For arguments’ sake, let’s assume that First Things is united in its doctrinal stance regarding church discipline. Would that necessarily mean they are in agreement on who constitutes an “unruly” church-member? What exactly makes a church-member “unruly”? Does holding conservative or progressive political views make one “unruly”? Knowing how touchy Conservatives are on this subject, I’m not going far out on a limb to guess that the editorial staff of First Things would take vehement issue with a pastor labeling some Conservative church-member “unruly” based on their political views.

But, let’s give Leithart the benefit of the doubt. Perhaps he has in mind some legitimate matter that calls for pastoral intervention. Does one need to be a catechized authority-hater to question whether church discipline could potentially devolve into exploitation? Or, based on what we’ve seen with our own eyes in far too many American churches, is that a legitimate and appropriate concern?

Is Severe Punishment for Criminals Really Unquestionable?The final authority relationship Leithart uses as an example is that of the state and its power over criminals. According to Leithart, the hypothetical authority-haters in this scenario really over-react. They accuse those who want “severe punishments for murders and rapists” of being “Nazis and Fascists”.

Is this realistic? Are proponents of stricter sentencing guidelines for perpetrators of sexual assault routinely accused of being Nazis? That doesn’t track. I think the clear implication here is the death penalty. Despite the caricature on the Right, liberal prosecutors aren’t letting murderers and rapists go free. Prosecutors, regardless of whether they vote Democrat or Republican, prosecute criminals. And I can’t remember any prosecutors of sexual assault cases being accused of being Nazis or Fascists.

But if, as I suspect, Leithart is using “severe punishments” as a euphemism for the death penalty, then it makes slightly more sense. I still don’t think proponents of the death penalty in America are routinely being compared to Nazis or Fascists. But, at least the comparison would be in the same ballpark.

Are catechized authority-haters the only ones who question whether the State should be imbued with the power to take life? Or, as history would show us, is this an ethical matter that has resulted in much wrestling among some of the church’s greatest minds? It would seem to me that, if Clement of Alexandria, Tertullian, and Augustine weren’t unanimous on the matter, then it shouldn’t so flippantly be considered settled.

But, what of restorative methods? Are Christians prohibited from even considering whether a person who has committed a heinous crime like murder or rape can be rehabilitated through restorative means? Are Christians only allowed to consider “severe punishments” in such cases? I don’t recall the Apostle Paul ever being “severely punished” for his role in the murder of St. Stephen, but maybe I missed that part.

Whence Comes Real Authority?The crux of Leithart’s argument is that because Jesus is a King, authority is good. But, Leithart also argues that Jesus redefines what it means to be a king and to have authority. He writes,

Jesus revolutionizes authority. He asserts his claim on the world by humbling himself. He doesn’t enter the world as an oiled ancient warrior, but as a helpless baby. The King isn’t born in a splendid palace but in a manger, as the son of a carpenter or mason. In his adulthood, he humbles himself further, even to death on a cross. As Tom Holland demonstrates in Dominion, the message of God on a cross permanently altered what we think authority is and what it’s for.”

Now that’s good preaching! Leithart forcefully asserts that Jesus turns our assumptions about authority upside-down, calling them into question. We would think a king would be born in a “splendid palace,” but Jesus wasn’t. We would think a king would be an “oiled ancient warrior,” but Jesus wasn’t. (I want credit for ignoring the part about warriors being “oiled”) We would think that a king would rule over the world with an iron fist, not humble himself to the point of being executed by the state, but that’s what Jesus does.

So, Leithart correctly argues, Jesus’s radical redefinition of “kingship” calls into question all our assumptions about power and authority.

But Leithart goes even further. He next argues that Jesus’s form of authority was actually the authorization of others.

When God’s kingdom comes, he gives those who receive him the authority of sons, heirs, co-rulers. Through his gift of filial authority, the Father’s Word enables us to reach our created destiny. The Word’s authority authorizes.”

Amen! I agree wholeheartedly with Leithart here. Jesus’s radical redefinition of “kingship” not only calls into question our assumptions about power and authority, it is characterized by sharing power and giving it away. “Co-ruling” is sharing power, in case anyone missed that. And “authorizing” others is giving them power.

If, as Leithart concludes, Jesus and his kingship teach us that “true authority doesn’t beat people down, but raises them up. Ruling isn’t lording over others, but serving them,” why would it be unfaithful to Jesus for anyone to question highly contentious and debatable methods of authority figures?

If, as Leithart concludes, “all authorities are called to mimic the heavenly king,” why would it be unfaithful to Jesus for anyone to question Patriarchy, Spanking, or the Death Penalty?

The implication is precisely the opposite. If Jesus and his Kingship define authority for us, and Jesus’s Kingship is characterized by “raising people up” and “serving them,” then Jesus’s disciples Must question all potentially harmful methods of exercising authority. Jesus’s disciples Must question whether fathers should “rule” their homes or parents should spank their kids. Jesus’s disciples Must question whether pastors should be able to label congregants “unruly” and discipline them without accountability, or whether the State should be able to take the life of a prisoner!

By teaching the Gospel of Jesus’s upside-down Kingdom authority, Leithart hasn’t made a case for the protection of Conservative positions, he’s completely undermined them. By teaching the Gospel of Jesus’s upside-down Kingdom authority, Leithart hasn’t made the case for Authority for Authority’s Own Sake, he’s completely undermined it. By teaching the Gospel of Jesus’s upside-down Kingdom authority, Leithart hasn’t made the case for Monarchy at all—he’s completely undermined it.

Democracy is more of a reflection of the shared power, others-authorizing, and servant-authority of Jesus than monarchy.

Egalitarianism is more of a reflection of the shared power, humility, and servant-authority of Jesus than Complementarianism.

Nonviolence is more of a reflection of the shared power, humility, and servant-authority of Jesus than “severe punishments.”

At every point, the upside-down Kingdom of Jesus leads us further and further away from the positions that Leithart takes as default modes of “authority.”

The message of Advent and Christmas isn’t that Authority is Good (much less Monarchy). No, the message of Advent and Christmas is that Jesus is Good and his life, teachings, miracles, death, and resurrection are the very definition of godly authority—authority that is so radically unlike our assumptions of authority that it calls into question and exposes the sinfulness of all human rule and authority.

August 6, 2023

PRE-ORDER FORGED

The Jesus Way calls us into community with others to form a new kind of family—a forged family.

In an era when our relationships with our families of origin are more complicated than ever, pastor T. C. Moore shows us how following the way of Jesus can lead us to forged families that are authentic and life-giving.

Our forged families are the ones who love us for who we are and show up for us when we’re in desperate need. Our forged families are the ones with whom we’re worked through conflict. Our forged families make us who we are, strengthen our faith, and sustain us through life’s many challenges.

Forged weaves together stories from the author’s over twenty years of experience with urban, multiethnic ministry all over the U.S., principles from scripture, and his own experience as an ex-gang member turned church planter to propose a way of approaching faith in community that rejects hierarchical, bureaucratic structures in favor of formative, inclusive friendships that last.

PRE-ORDER NOW AVAILABLEForged is now available for Pre-order from these outlets:

July 3, 2022

Belfast, Belovedness, and the Banksy Tunnel

Last week, I embarked upon my first time traveling internationally to England and Northern Ireland. We spent two days in London, two days in Belfast, and three days in Ballycastle, Northern Ireland. Osheta has been journeying alongside peacemakers from around the United States along with peacemakers in the United Kingdom as part of the Journey of Hope 2022. She connected with this cohort of peacemakers through The Global Immersion Project, led by Jer Swigart. Osheta played a pastoral role, facilitating and guiding participants in spiritual practices, while 40 peacemakers gathered at the storied Corrymeela Community in Ballycastle, Northern Ireland. While she served, I had the privilege of tagging along and experiencing the beauty of the Emerald Isle.

Belfast, Northern Ireland #bwg_container1_0 #bwg_container2_0 .bwg-container-0.bwg-standard-thumbnails { width: 904px; justify-content: center; margin:0 auto !important; background-color: rgba(255, 255, 255, 0.00); padding-left: 4px; padding-top: 4px; max-width: 100%; } #bwg_container1_0 #bwg_container2_0 .bwg-container-0.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-item { justify-content: flex-start; max-width: 180px; width: 180px !important; } #bwg_container1_0 #bwg_container2_0 .bwg-container-0.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-item > a { margin-right: 4px; margin-bottom: 4px; } #bwg_container1_0 #bwg_container2_0 .bwg-container-0.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-item0 { padding: 0px; background-color:rgba(0,0,0, 0.30); border: 0px none #CCCCCC; opacity: 1.00; border-radius: 0; box-shadow: ; } #bwg_container1_0 #bwg_container2_0 .bwg-container-0.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-item1 img { max-height: none; max-width: none; padding: 0 !important; } @media only screen and (min-width: 480px) { #bwg_container1_0 #bwg_container2_0 .bwg-container-0.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-item1 img { -webkit-transition: all .3s; transition: all .3s; } #bwg_container1_0 #bwg_container2_0 .bwg-container-0.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-item1 img:hover { -ms-transform: scale(1.08); -webkit-transform: scale(1.08); transform: scale(1.08); } } #bwg_container1_0 #bwg_container2_0 .bwg-container-0.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-item1 { padding-top: 50%; } #bwg_container1_0 #bwg_container2_0 .bwg-container-0.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-title2, #bwg_container1_0 #bwg_container2_0 .bwg-container-0.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-ecommerce2 { color: #323A45; font-family: Ubuntu; font-size: 16px; font-weight: bold; padding: 2px; text-shadow: ; max-height: 100%; } #bwg_container1_0 #bwg_container2_0 .bwg-container-0.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-thumb-description span { color: #323A45; font-family: Ubuntu; font-size: 12px; max-height: 100%; word-wrap: break-word; } #bwg_container1_0 #bwg_container2_0 .bwg-container-0.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-play-icon2 { font-size: 32px; } #bwg_container1_0 #bwg_container2_0 .bwg-container-0.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-ecommerce2 { font-size: 19.2px; color: #323A45; }

/*pagination styles*/ #bwg_container1_0 #bwg_container2_0 .tablenav-pages_0 { text-align: center; font-size: 12px; font-family: Ubuntu; font-weight: bold; color: #666666; margin: 6px 0 4px; display: block; } @media only screen and (max-width : 320px) { #bwg_container1_0 #bwg_container2_0 .displaying-num_0 { display: none; } } #bwg_container1_0 #bwg_container2_0 .displaying-num_0 { font-size: 12px; font-family: Ubuntu; font-weight: bold; color: #666666; margin-right: 10px; vertical-align: middle; } #bwg_container1_0 #bwg_container2_0 .paging-input_0 { font-size: 12px; font-family: Ubuntu; font-weight: bold; color: #666666; vertical-align: middle; } #bwg_container1_0 #bwg_container2_0 .tablenav-pages_0 a.disabled, #bwg_container1_0 #bwg_container2_0 .tablenav-pages_0 a.disabled:hover, #bwg_container1_0 #bwg_container2_0 .tablenav-pages_0 a.disabled:focus, #bwg_container1_0 #bwg_container2_0 .tablenav-pages_0 input.bwg_current_page { cursor: default; color: rgba(102, 102, 102, 0.5); } #bwg_container1_0 #bwg_container2_0 .tablenav-pages_0 a, #bwg_container1_0 #bwg_container2_0 .tablenav-pages_0 input.bwg_current_page { cursor: pointer; text-align: center; font-size: 12px; font-family: Ubuntu; font-weight: bold; color: #666666; text-decoration: none; padding: 3px 6px; margin: 0; border-radius: 0; border-style: solid; border-width: 1px; border-color: #E3E3E3; background-color: #FFFFFF; opacity: 1.00; box-shadow: 0; transition: all 0.3s ease 0s;-webkit-transition: all 0.3s ease 0s; } if( jQuery('.bwg_nav_cont_0').length > 1 ) { jQuery('.bwg_nav_cont_0').first().remove() } function spider_page_0(cur, x, y, load_more) { if (typeof load_more == "undefined") { var load_more = false; } if (jQuery(cur).hasClass('disabled')) { return false; } var items_county_0 = 1; switch (y) { case 1: if (x >= items_county_0) { document.getElementById('page_number_0').value = items_county_0; } else { document.getElementById('page_number_0').value = x + 1; } break; case 2: document.getElementById('page_number_0').value = items_county_0; break; case -1: if (x == 1) { document.getElementById('page_number_0').value = 1; } else { document.getElementById('page_number_0').value = x - 1; } break; case -2: document.getElementById('page_number_0').value = 1; break; case 0: document.getElementById('page_number_0').value = x; break; default: document.getElementById('page_number_0').value = 1; } bwg_ajax('gal_front_form_0', '0', 'bwg_thumbnails_0', '0', '', 'gallery', 0, '', '', load_more, '', 1); } jQuery('.first-page-0').on('click', function () { spider_page_0(this, 1, -2, 'numeric'); return false; }); jQuery('.prev-page-0').on('click', function () { spider_page_0(this, 1, -1, 'numeric'); return false; }); jQuery('.next-page-0').on('click', function () { spider_page_0(this, 1, 1, 'numeric'); return false; }); jQuery('.last-page-0').on('click', function () { spider_page_0(this, 1, 2, 'numeric'); return false; }); /* Change page on input enter. */ function bwg_change_page_0( e, that ) { if ( e.key == 'Enter' ) { var to_page = parseInt(jQuery(that).val()); var pages_count = jQuery(that).parents(".pagination-links").data("pages-count"); var current_url_param = jQuery(that).attr('data-url-info'); if (to_page > pages_count) { to_page = 1; } spider_page_0(this, to_page, 0, 'numeric'); return false; } return true; } jQuery('.bwg_load_btn_0').on('click', function () { spider_page_0(this, 1, 1, true); return false; }); #bwg_container1_0 #bwg_container2_0 #spider_popup_overlay_0 { background-color: #EEEEEE; opacity: 0.60; } if (document.readyState === 'complete') { if( typeof bwg_main_ready == 'function' ) { if ( jQuery("#bwg_container1_0").height() ) { bwg_main_ready(jQuery("#bwg_container1_0")); } } } else { document.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', function() { if( typeof bwg_main_ready == 'function' ) { if ( jQuery("#bwg_container1_0").height() ) { bwg_main_ready(jQuery("#bwg_container1_0")); } } }); }

/*pagination styles*/ #bwg_container1_0 #bwg_container2_0 .tablenav-pages_0 { text-align: center; font-size: 12px; font-family: Ubuntu; font-weight: bold; color: #666666; margin: 6px 0 4px; display: block; } @media only screen and (max-width : 320px) { #bwg_container1_0 #bwg_container2_0 .displaying-num_0 { display: none; } } #bwg_container1_0 #bwg_container2_0 .displaying-num_0 { font-size: 12px; font-family: Ubuntu; font-weight: bold; color: #666666; margin-right: 10px; vertical-align: middle; } #bwg_container1_0 #bwg_container2_0 .paging-input_0 { font-size: 12px; font-family: Ubuntu; font-weight: bold; color: #666666; vertical-align: middle; } #bwg_container1_0 #bwg_container2_0 .tablenav-pages_0 a.disabled, #bwg_container1_0 #bwg_container2_0 .tablenav-pages_0 a.disabled:hover, #bwg_container1_0 #bwg_container2_0 .tablenav-pages_0 a.disabled:focus, #bwg_container1_0 #bwg_container2_0 .tablenav-pages_0 input.bwg_current_page { cursor: default; color: rgba(102, 102, 102, 0.5); } #bwg_container1_0 #bwg_container2_0 .tablenav-pages_0 a, #bwg_container1_0 #bwg_container2_0 .tablenav-pages_0 input.bwg_current_page { cursor: pointer; text-align: center; font-size: 12px; font-family: Ubuntu; font-weight: bold; color: #666666; text-decoration: none; padding: 3px 6px; margin: 0; border-radius: 0; border-style: solid; border-width: 1px; border-color: #E3E3E3; background-color: #FFFFFF; opacity: 1.00; box-shadow: 0; transition: all 0.3s ease 0s;-webkit-transition: all 0.3s ease 0s; } if( jQuery('.bwg_nav_cont_0').length > 1 ) { jQuery('.bwg_nav_cont_0').first().remove() } function spider_page_0(cur, x, y, load_more) { if (typeof load_more == "undefined") { var load_more = false; } if (jQuery(cur).hasClass('disabled')) { return false; } var items_county_0 = 1; switch (y) { case 1: if (x >= items_county_0) { document.getElementById('page_number_0').value = items_county_0; } else { document.getElementById('page_number_0').value = x + 1; } break; case 2: document.getElementById('page_number_0').value = items_county_0; break; case -1: if (x == 1) { document.getElementById('page_number_0').value = 1; } else { document.getElementById('page_number_0').value = x - 1; } break; case -2: document.getElementById('page_number_0').value = 1; break; case 0: document.getElementById('page_number_0').value = x; break; default: document.getElementById('page_number_0').value = 1; } bwg_ajax('gal_front_form_0', '0', 'bwg_thumbnails_0', '0', '', 'gallery', 0, '', '', load_more, '', 1); } jQuery('.first-page-0').on('click', function () { spider_page_0(this, 1, -2, 'numeric'); return false; }); jQuery('.prev-page-0').on('click', function () { spider_page_0(this, 1, -1, 'numeric'); return false; }); jQuery('.next-page-0').on('click', function () { spider_page_0(this, 1, 1, 'numeric'); return false; }); jQuery('.last-page-0').on('click', function () { spider_page_0(this, 1, 2, 'numeric'); return false; }); /* Change page on input enter. */ function bwg_change_page_0( e, that ) { if ( e.key == 'Enter' ) { var to_page = parseInt(jQuery(that).val()); var pages_count = jQuery(that).parents(".pagination-links").data("pages-count"); var current_url_param = jQuery(that).attr('data-url-info'); if (to_page > pages_count) { to_page = 1; } spider_page_0(this, to_page, 0, 'numeric'); return false; } return true; } jQuery('.bwg_load_btn_0').on('click', function () { spider_page_0(this, 1, 1, true); return false; }); #bwg_container1_0 #bwg_container2_0 #spider_popup_overlay_0 { background-color: #EEEEEE; opacity: 0.60; } if (document.readyState === 'complete') { if( typeof bwg_main_ready == 'function' ) { if ( jQuery("#bwg_container1_0").height() ) { bwg_main_ready(jQuery("#bwg_container1_0")); } } } else { document.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', function() { if( typeof bwg_main_ready == 'function' ) { if ( jQuery("#bwg_container1_0").height() ) { bwg_main_ready(jQuery("#bwg_container1_0")); } } }); } In Belfast, we briefly toured some of the sites where this region has suffered from sectarian violence and religious segregation. We got a crash-course in what’s known as “The Troubles”—the conflict that has persisted between Catholics and Protestants, Loyalists and Republicans. We visited neighborhoods that have been home to paramilitary groups which have waged an urban war on their perceived enemies and saw murals that remain to this day commemorating (even celebrating) their attacks. While the famed “Good Friday Agreement” has brought about a time of relative peace in Belfast, locals don’t believe The Troubles are completely over. Even now, a so-called “Peace Wall” stands 40+ feet tall separating these communities and gates that control the flow of traffic between them are closed at night. What does it mean to be a Peacemaker in a city like Belfast today?

The Corrymeela Community #bwg_container1_1 #bwg_container2_1 .bwg-container-1.bwg-standard-thumbnails { width: 904px; justify-content: center; margin:0 auto !important; background-color: rgba(255, 255, 255, 0.00); padding-left: 4px; padding-top: 4px; max-width: 100%; } #bwg_container1_1 #bwg_container2_1 .bwg-container-1.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-item { justify-content: flex-start; max-width: 180px; width: 180px !important; } #bwg_container1_1 #bwg_container2_1 .bwg-container-1.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-item > a { margin-right: 4px; margin-bottom: 4px; } #bwg_container1_1 #bwg_container2_1 .bwg-container-1.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-item0 { padding: 0px; background-color:rgba(0,0,0, 0.30); border: 0px none #CCCCCC; opacity: 1.00; border-radius: 0; box-shadow: ; } #bwg_container1_1 #bwg_container2_1 .bwg-container-1.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-item1 img { max-height: none; max-width: none; padding: 0 !important; } @media only screen and (min-width: 480px) { #bwg_container1_1 #bwg_container2_1 .bwg-container-1.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-item1 img { -webkit-transition: all .3s; transition: all .3s; } #bwg_container1_1 #bwg_container2_1 .bwg-container-1.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-item1 img:hover { -ms-transform: scale(1.08); -webkit-transform: scale(1.08); transform: scale(1.08); } } #bwg_container1_1 #bwg_container2_1 .bwg-container-1.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-item1 { padding-top: 50%; } #bwg_container1_1 #bwg_container2_1 .bwg-container-1.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-title2, #bwg_container1_1 #bwg_container2_1 .bwg-container-1.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-ecommerce2 { color: #323A45; font-family: Ubuntu; font-size: 16px; font-weight: bold; padding: 2px; text-shadow: ; max-height: 100%; } #bwg_container1_1 #bwg_container2_1 .bwg-container-1.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-thumb-description span { color: #323A45; font-family: Ubuntu; font-size: 12px; max-height: 100%; word-wrap: break-word; } #bwg_container1_1 #bwg_container2_1 .bwg-container-1.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-play-icon2 { font-size: 32px; } #bwg_container1_1 #bwg_container2_1 .bwg-container-1.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-ecommerce2 { font-size: 19.2px; color: #323A45; }

/*pagination styles*/ #bwg_container1_1 #bwg_container2_1 .tablenav-pages_1 { text-align: center; font-size: 12px; font-family: Ubuntu; font-weight: bold; color: #666666; margin: 6px 0 4px; display: block; } @media only screen and (max-width : 320px) { #bwg_container1_1 #bwg_container2_1 .displaying-num_1 { display: none; } } #bwg_container1_1 #bwg_container2_1 .displaying-num_1 { font-size: 12px; font-family: Ubuntu; font-weight: bold; color: #666666; margin-right: 10px; vertical-align: middle; } #bwg_container1_1 #bwg_container2_1 .paging-input_1 { font-size: 12px; font-family: Ubuntu; font-weight: bold; color: #666666; vertical-align: middle; } #bwg_container1_1 #bwg_container2_1 .tablenav-pages_1 a.disabled, #bwg_container1_1 #bwg_container2_1 .tablenav-pages_1 a.disabled:hover, #bwg_container1_1 #bwg_container2_1 .tablenav-pages_1 a.disabled:focus, #bwg_container1_1 #bwg_container2_1 .tablenav-pages_1 input.bwg_current_page { cursor: default; color: rgba(102, 102, 102, 0.5); } #bwg_container1_1 #bwg_container2_1 .tablenav-pages_1 a, #bwg_container1_1 #bwg_container2_1 .tablenav-pages_1 input.bwg_current_page { cursor: pointer; text-align: center; font-size: 12px; font-family: Ubuntu; font-weight: bold; color: #666666; text-decoration: none; padding: 3px 6px; margin: 0; border-radius: 0; border-style: solid; border-width: 1px; border-color: #E3E3E3; background-color: #FFFFFF; opacity: 1.00; box-shadow: 0; transition: all 0.3s ease 0s;-webkit-transition: all 0.3s ease 0s; } if( jQuery('.bwg_nav_cont_1').length > 1 ) { jQuery('.bwg_nav_cont_1').first().remove() } function spider_page_1(cur, x, y, load_more) { if (typeof load_more == "undefined") { var load_more = false; } if (jQuery(cur).hasClass('disabled')) { return false; } var items_county_1 = 1; switch (y) { case 1: if (x >= items_county_1) { document.getElementById('page_number_1').value = items_county_1; } else { document.getElementById('page_number_1').value = x + 1; } break; case 2: document.getElementById('page_number_1').value = items_county_1; break; case -1: if (x == 1) { document.getElementById('page_number_1').value = 1; } else { document.getElementById('page_number_1').value = x - 1; } break; case -2: document.getElementById('page_number_1').value = 1; break; case 0: document.getElementById('page_number_1').value = x; break; default: document.getElementById('page_number_1').value = 1; } bwg_ajax('gal_front_form_1', '1', 'bwg_thumbnails_1', '0', '', 'gallery', 0, '', '', load_more, '', 1); } jQuery('.first-page-1').on('click', function () { spider_page_1(this, 1, -2, 'numeric'); return false; }); jQuery('.prev-page-1').on('click', function () { spider_page_1(this, 1, -1, 'numeric'); return false; }); jQuery('.next-page-1').on('click', function () { spider_page_1(this, 1, 1, 'numeric'); return false; }); jQuery('.last-page-1').on('click', function () { spider_page_1(this, 1, 2, 'numeric'); return false; }); /* Change page on input enter. */ function bwg_change_page_1( e, that ) { if ( e.key == 'Enter' ) { var to_page = parseInt(jQuery(that).val()); var pages_count = jQuery(that).parents(".pagination-links").data("pages-count"); var current_url_param = jQuery(that).attr('data-url-info'); if (to_page > pages_count) { to_page = 1; } spider_page_1(this, to_page, 0, 'numeric'); return false; } return true; } jQuery('.bwg_load_btn_1').on('click', function () { spider_page_1(this, 1, 1, true); return false; }); #bwg_container1_1 #bwg_container2_1 #spider_popup_overlay_1 { background-color: #EEEEEE; opacity: 0.60; } if (document.readyState === 'complete') { if( typeof bwg_main_ready == 'function' ) { if ( jQuery("#bwg_container1_1").height() ) { bwg_main_ready(jQuery("#bwg_container1_1")); } } } else { document.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', function() { if( typeof bwg_main_ready == 'function' ) { if ( jQuery("#bwg_container1_1").height() ) { bwg_main_ready(jQuery("#bwg_container1_1")); } } }); }

/*pagination styles*/ #bwg_container1_1 #bwg_container2_1 .tablenav-pages_1 { text-align: center; font-size: 12px; font-family: Ubuntu; font-weight: bold; color: #666666; margin: 6px 0 4px; display: block; } @media only screen and (max-width : 320px) { #bwg_container1_1 #bwg_container2_1 .displaying-num_1 { display: none; } } #bwg_container1_1 #bwg_container2_1 .displaying-num_1 { font-size: 12px; font-family: Ubuntu; font-weight: bold; color: #666666; margin-right: 10px; vertical-align: middle; } #bwg_container1_1 #bwg_container2_1 .paging-input_1 { font-size: 12px; font-family: Ubuntu; font-weight: bold; color: #666666; vertical-align: middle; } #bwg_container1_1 #bwg_container2_1 .tablenav-pages_1 a.disabled, #bwg_container1_1 #bwg_container2_1 .tablenav-pages_1 a.disabled:hover, #bwg_container1_1 #bwg_container2_1 .tablenav-pages_1 a.disabled:focus, #bwg_container1_1 #bwg_container2_1 .tablenav-pages_1 input.bwg_current_page { cursor: default; color: rgba(102, 102, 102, 0.5); } #bwg_container1_1 #bwg_container2_1 .tablenav-pages_1 a, #bwg_container1_1 #bwg_container2_1 .tablenav-pages_1 input.bwg_current_page { cursor: pointer; text-align: center; font-size: 12px; font-family: Ubuntu; font-weight: bold; color: #666666; text-decoration: none; padding: 3px 6px; margin: 0; border-radius: 0; border-style: solid; border-width: 1px; border-color: #E3E3E3; background-color: #FFFFFF; opacity: 1.00; box-shadow: 0; transition: all 0.3s ease 0s;-webkit-transition: all 0.3s ease 0s; } if( jQuery('.bwg_nav_cont_1').length > 1 ) { jQuery('.bwg_nav_cont_1').first().remove() } function spider_page_1(cur, x, y, load_more) { if (typeof load_more == "undefined") { var load_more = false; } if (jQuery(cur).hasClass('disabled')) { return false; } var items_county_1 = 1; switch (y) { case 1: if (x >= items_county_1) { document.getElementById('page_number_1').value = items_county_1; } else { document.getElementById('page_number_1').value = x + 1; } break; case 2: document.getElementById('page_number_1').value = items_county_1; break; case -1: if (x == 1) { document.getElementById('page_number_1').value = 1; } else { document.getElementById('page_number_1').value = x - 1; } break; case -2: document.getElementById('page_number_1').value = 1; break; case 0: document.getElementById('page_number_1').value = x; break; default: document.getElementById('page_number_1').value = 1; } bwg_ajax('gal_front_form_1', '1', 'bwg_thumbnails_1', '0', '', 'gallery', 0, '', '', load_more, '', 1); } jQuery('.first-page-1').on('click', function () { spider_page_1(this, 1, -2, 'numeric'); return false; }); jQuery('.prev-page-1').on('click', function () { spider_page_1(this, 1, -1, 'numeric'); return false; }); jQuery('.next-page-1').on('click', function () { spider_page_1(this, 1, 1, 'numeric'); return false; }); jQuery('.last-page-1').on('click', function () { spider_page_1(this, 1, 2, 'numeric'); return false; }); /* Change page on input enter. */ function bwg_change_page_1( e, that ) { if ( e.key == 'Enter' ) { var to_page = parseInt(jQuery(that).val()); var pages_count = jQuery(that).parents(".pagination-links").data("pages-count"); var current_url_param = jQuery(that).attr('data-url-info'); if (to_page > pages_count) { to_page = 1; } spider_page_1(this, to_page, 0, 'numeric'); return false; } return true; } jQuery('.bwg_load_btn_1').on('click', function () { spider_page_1(this, 1, 1, true); return false; }); #bwg_container1_1 #bwg_container2_1 #spider_popup_overlay_1 { background-color: #EEEEEE; opacity: 0.60; } if (document.readyState === 'complete') { if( typeof bwg_main_ready == 'function' ) { if ( jQuery("#bwg_container1_1").height() ) { bwg_main_ready(jQuery("#bwg_container1_1")); } } } else { document.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', function() { if( typeof bwg_main_ready == 'function' ) { if ( jQuery("#bwg_container1_1").height() ) { bwg_main_ready(jQuery("#bwg_container1_1")); } } }); } For the lion share of our time in the UK, we stayed at the storied Corrymeela Community in Ballycastle, Northern Ireland along the coast outside Belfast. For decades, this place has been a center for learning, growing, and forming peacemakers. Host to global leaders like Mother Teresa and the Dalai Lama, Corrymeela is a spiritual oasis amidst a conflict zone. At the center of the village is a sacred worship space called the Croí, which is the Irish word for “heart.” The building itself is shaped like the inner-ear calling upon visitors to listen to their own hearts and the heart of God.

Tagging the Leake Street Tunnel (AKA the Banksy Tunnel) #bwg_container1_2 #bwg_container2_2 .bwg-container-2.bwg-standard-thumbnails { width: 904px; justify-content: center; margin:0 auto !important; background-color: rgba(255, 255, 255, 0.00); padding-left: 4px; padding-top: 4px; max-width: 100%; } #bwg_container1_2 #bwg_container2_2 .bwg-container-2.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-item { justify-content: flex-start; max-width: 180px; width: 180px !important; } #bwg_container1_2 #bwg_container2_2 .bwg-container-2.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-item > a { margin-right: 4px; margin-bottom: 4px; } #bwg_container1_2 #bwg_container2_2 .bwg-container-2.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-item0 { padding: 0px; background-color:rgba(0,0,0, 0.30); border: 0px none #CCCCCC; opacity: 1.00; border-radius: 0; box-shadow: ; } #bwg_container1_2 #bwg_container2_2 .bwg-container-2.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-item1 img { max-height: none; max-width: none; padding: 0 !important; } @media only screen and (min-width: 480px) { #bwg_container1_2 #bwg_container2_2 .bwg-container-2.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-item1 img { -webkit-transition: all .3s; transition: all .3s; } #bwg_container1_2 #bwg_container2_2 .bwg-container-2.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-item1 img:hover { -ms-transform: scale(1.08); -webkit-transform: scale(1.08); transform: scale(1.08); } } #bwg_container1_2 #bwg_container2_2 .bwg-container-2.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-item1 { padding-top: 50%; } #bwg_container1_2 #bwg_container2_2 .bwg-container-2.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-title2, #bwg_container1_2 #bwg_container2_2 .bwg-container-2.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-ecommerce2 { color: #323A45; font-family: Ubuntu; font-size: 16px; font-weight: bold; padding: 2px; text-shadow: ; max-height: 100%; } #bwg_container1_2 #bwg_container2_2 .bwg-container-2.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-thumb-description span { color: #323A45; font-family: Ubuntu; font-size: 12px; max-height: 100%; word-wrap: break-word; } #bwg_container1_2 #bwg_container2_2 .bwg-container-2.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-play-icon2 { font-size: 32px; } #bwg_container1_2 #bwg_container2_2 .bwg-container-2.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-ecommerce2 { font-size: 19.2px; color: #323A45; }

/*pagination styles*/ #bwg_container1_2 #bwg_container2_2 .tablenav-pages_2 { text-align: center; font-size: 12px; font-family: Ubuntu; font-weight: bold; color: #666666; margin: 6px 0 4px; display: block; } @media only screen and (max-width : 320px) { #bwg_container1_2 #bwg_container2_2 .displaying-num_2 { display: none; } } #bwg_container1_2 #bwg_container2_2 .displaying-num_2 { font-size: 12px; font-family: Ubuntu; font-weight: bold; color: #666666; margin-right: 10px; vertical-align: middle; } #bwg_container1_2 #bwg_container2_2 .paging-input_2 { font-size: 12px; font-family: Ubuntu; font-weight: bold; color: #666666; vertical-align: middle; } #bwg_container1_2 #bwg_container2_2 .tablenav-pages_2 a.disabled, #bwg_container1_2 #bwg_container2_2 .tablenav-pages_2 a.disabled:hover, #bwg_container1_2 #bwg_container2_2 .tablenav-pages_2 a.disabled:focus, #bwg_container1_2 #bwg_container2_2 .tablenav-pages_2 input.bwg_current_page { cursor: default; color: rgba(102, 102, 102, 0.5); } #bwg_container1_2 #bwg_container2_2 .tablenav-pages_2 a, #bwg_container1_2 #bwg_container2_2 .tablenav-pages_2 input.bwg_current_page { cursor: pointer; text-align: center; font-size: 12px; font-family: Ubuntu; font-weight: bold; color: #666666; text-decoration: none; padding: 3px 6px; margin: 0; border-radius: 0; border-style: solid; border-width: 1px; border-color: #E3E3E3; background-color: #FFFFFF; opacity: 1.00; box-shadow: 0; transition: all 0.3s ease 0s;-webkit-transition: all 0.3s ease 0s; } if( jQuery('.bwg_nav_cont_2').length > 1 ) { jQuery('.bwg_nav_cont_2').first().remove() } function spider_page_2(cur, x, y, load_more) { if (typeof load_more == "undefined") { var load_more = false; } if (jQuery(cur).hasClass('disabled')) { return false; } var items_county_2 = 1; switch (y) { case 1: if (x >= items_county_2) { document.getElementById('page_number_2').value = items_county_2; } else { document.getElementById('page_number_2').value = x + 1; } break; case 2: document.getElementById('page_number_2').value = items_county_2; break; case -1: if (x == 1) { document.getElementById('page_number_2').value = 1; } else { document.getElementById('page_number_2').value = x - 1; } break; case -2: document.getElementById('page_number_2').value = 1; break; case 0: document.getElementById('page_number_2').value = x; break; default: document.getElementById('page_number_2').value = 1; } bwg_ajax('gal_front_form_2', '2', 'bwg_thumbnails_2', '0', '', 'gallery', 0, '', '', load_more, '', 1); } jQuery('.first-page-2').on('click', function () { spider_page_2(this, 1, -2, 'numeric'); return false; }); jQuery('.prev-page-2').on('click', function () { spider_page_2(this, 1, -1, 'numeric'); return false; }); jQuery('.next-page-2').on('click', function () { spider_page_2(this, 1, 1, 'numeric'); return false; }); jQuery('.last-page-2').on('click', function () { spider_page_2(this, 1, 2, 'numeric'); return false; }); /* Change page on input enter. */ function bwg_change_page_2( e, that ) { if ( e.key == 'Enter' ) { var to_page = parseInt(jQuery(that).val()); var pages_count = jQuery(that).parents(".pagination-links").data("pages-count"); var current_url_param = jQuery(that).attr('data-url-info'); if (to_page > pages_count) { to_page = 1; } spider_page_2(this, to_page, 0, 'numeric'); return false; } return true; } jQuery('.bwg_load_btn_2').on('click', function () { spider_page_2(this, 1, 1, true); return false; }); #bwg_container1_2 #bwg_container2_2 #spider_popup_overlay_2 { background-color: #EEEEEE; opacity: 0.60; } if (document.readyState === 'complete') { if( typeof bwg_main_ready == 'function' ) { if ( jQuery("#bwg_container1_2").height() ) { bwg_main_ready(jQuery("#bwg_container1_2")); } } } else { document.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', function() { if( typeof bwg_main_ready == 'function' ) { if ( jQuery("#bwg_container1_2").height() ) { bwg_main_ready(jQuery("#bwg_container1_2")); } } }); }