T.C. Moore's Blog, page 4

June 6, 2016

Chemical & Idolatry: Reflections on a Jack Garratt Track and the Apocalypse of John

Because here’s something else that’s weird but true: in the day-to-day trenches of adult life, there is actually no such thing as atheism. There is no such thing as not worshipping. Everybody worships. The only choice we get is what to worship. And the compelling reason for maybe choosing some sort of god or spiritual-type thing to worship—be it J.C. or Allah, be it YHWH or the Wiccan Mother Goddess, or the Four Noble Truths, or some inviolable set of ethical principles—is that pretty much anything else you worship will eat you alive. If you worship money and things, if they are where you tap real meaning in life, then you will never have enough, never feel you have enough. It’s the truth. Worship your body and beauty and sexual allure and you will always feel ugly. And when time and age start showing, you will die a million deaths before they finally plant you. On one level, we all know this stuff already. It’s been codified as myths, proverbs, clichés, epigrams, parables; the skeleton of every great story. The whole trick is keeping the truth up front in daily consciousness. Worship power, you will end up feeling weak and afraid, and you will need ever more power over others to numb you to your own fear. Worship your intellect, being seen as smart, you will end up feeling stupid, a fraud, always on the verge of being found out. But the insidious thing about these forms of worship is not that they’re evil or sinful, it’s that they’re unconscious. They are default settings. They’re the kind of worship you just gradually slip into, day after day, getting more and more selective about what you see and how you measure value without ever being fully aware that that’s what you’re doing.

— David Foster Wallace, “This is Water”

Late last year, I fell headlong into the music of Jack Garratt. It started with his EP, Remnants, and continued with the release of his first full album, Phase. There’s too much to say about my love for his music. Suffice to say I find it enchanting.

Meanwhile, in my teaching capacity as a pastor, I’ve been immersed in the study of Revelation. Rather than charting the Great Tribulation, or attempting to decipher which rogue agent on the world’s stage is the “antichrist,” or some such quixotic project (as Dispensationalists are want to do), I’ve been teaching John’s Apocalypse using the cruciform-centric hermeneutic that has been developed by such scholars as Richard Bauckham, Michael J. Gorman, N. T. Wright, and Greg Boyd. I’ve also been learning from works by both David DeSilva and Brian Blount, who read it through the lenses of postcolonial empire criticism and the experience of the African American church in America, respectively. And I also have to give props to Brian Zahnd’s excellent teaching ministry via the Word of Life podcast. He’s spent some extensive time in Revelation in recent months/years and it has been highly formative.

A second lens through which I’ve been reading Revelation is pedagogical. For this I blame the works of James K. A. Smith—particularly his book Desiring the Kingdom, of which he has recently published a layman’s version called You Are What You Love. Smith has succeeded in shifting my focus as a teacher from the dissemination of information to the inspiration of imaginations for the purpose of spiritual formation. (Not that I’ve mastered this; I’ve still got a lot of pedagogical baggage to overcome.)

One of the unexpected discoveries I’ve made thus far has been just how much of Revelation is pastorally concerned with spiritual formation. This should have been more obvious to me, considering that the book is so clearly addressed to seven churches from their bishop. However, I’ve spent so much of my Christian life surrounded by those who read this book as a roadmap to the “end times,” that the pastoral value of the book has rarely been presented as anything more than its ability to predict the future.

This brings me to “Chemical” by Jack Garratt.

Phase has become the soundtrack to my life for the past several months. I listen to it in the car and I listen to it while I write sermons. “Chemical” is one of the tracks that has fascinated me the most. What initially captured my attention was this:

And when you pray, he will not answer

Although you may hear voices on your mind

They won’t be kind

And when you pray, he will not answer

I know this for I ask him all the time

To reassure my mind

Naturally, my pastoral ears perk up when prayer is mentioned. But this is clearly not a positive assessment. I’m almost ashamed to admit I didn’t understand what this track was about until I watched the video—and then the brilliance of this track blew my mind.

John of Patmos does something unparalleled in the New Testament. Instead of writing in the didactic style of the epistles, which Evangelical Modernists love, or the narrative style of the Gospels and Acts, he writes in the apocalyptic mode of a Hebrew prophet. He writes a book that takes many of the things Jesus preached in his famous “Olivet Discourse” and expands them into something that resembles a Greek drama more than a sermon. Relentlessly paraded before the eyes of our imaginations is a graphic and often grotesque onslaught of nightmarishly disturbing pictures. But as the cruciform-centric hermeneutic has taught us, these images are not meant to be taken as a journalistic, if phenomenological, account of future events. Instead, they are symbols of realities as true today as they were nineteen hundred years ago.

The Seer’s primary pastoral concern is the vision of ‘the good life’ toward which these fledgling churches (and by extension our churches today) were living. Every day, in a thousand different ways, they and we are tempted to place our trust in a story that is not the story of Jesus’s incarnation, self-giving death, and resurrection. The story in John’s day was the “Pax Romana”; the story for many of us today is the “American Dream.” The way John combats this lie is with the truth that empire is beastly and to follow its way is adultery for the people whom God has redeemed. John gives his congregations a new imagining of what ‘the good life’ is all about. Instead of conquest as violent domination, conquest becomes giving faithful witness to God’s grace in and through Jesus. The Lion of the Tribe of Judah, Messiah Jesus, is revealed as the little, slaughtered Lamb who yet stands and reigns from the very center of the God’s throne. True power is not located in the military might of Rome’s armies but in the self-giving love and wisdom of God demonstrated on the Cross and in the Resurrection.

“Revelation does not contain two competing Christologies and theologies—one of power and one of weakness—symbolized by the Lion and the Lamb, respectively. Rather, Revelation presents Christ as the Lion who reigns as the Lamb, not in spite of being the Lamb. […] ‘Lamb power’ is ‘God power,’ and ‘God power’ is ‘Lamb power.’ If these claims are untrue, then Jesus is not in any meaningful way a faithful witness.” [1]

The New Heaven and New Earth is a vision the world gone wrong finally made right. It is a reimagining of the vision of shalom ubiquitous among the writings of the Hebrew prophets—not just some tranquil “peace,” but the world as it should be. This is the vision the churches are to be proleptically embodying now in part as a foretaste of what’s to come.

But, like a fish in water, we unconsciously swim in the current of our surrounding culture and the desires of our hearts are molded and shaped by our environment. We are indoctrinated into believing that ‘the good life’ is found in the acquisition of power, wealth, and pleasure. We surrender our agency to the pursuit of these ends and we become instruments of the powers that be. This is what the psalmist is describing when he warns that placing our trust in human-made idols numbs us to the life-giving Spirit of the Creator God.

The idols of the nations are merely things of silver and gold, shaped by human hands. They have mouths but cannot speak, and eyes but cannot see. They have ears but cannot hear, and mouths but cannot breathe. And those who make idols are just like them, as are all who trust in them. — Psalm 135.15-18 NLT

Here’s how N. T. Wright puts it:

“You become what you worship: so, if you worship that which is not God, you become something other than the image-bearing human being you were meant and made to be. […] Worship idols—blind, deaf, lifeless things—and you become blind, deaf and lifeless yourself. Murder, magic, fornication and theft are all forms of blindness, deafness and deadliness, snatching at the quick fix for gain, power or pleasure while forfeiting another bit of genuine humanness.” [2]

“Chemical” is about the power we give our idols—with which they mercilessly destroy our humanity. The “love” idols have for us is the “love” of an abusive master. It is not a relationship of mutuality, interdependence, nor understanding; it is a relationship of utter domination. As David Foster Wallace put it, “[they] will eat you alive.”

My love is overdone, selfish and domineering

It won’t sit up on the shelf

So don’t try to reason with my love

My love is powerful, ruthless and unforgiving

It won’t think beyond itself

So don’t try to reason with my love

My love is chemical, shallow and chauvinistic

It’s an arrogant display

So don’t try to reason with my love

The apostle Paul famously describes love in a letter to the Jesus-disciples of Corinth. If you’ve ever been to a wedding, you probably know at least this much Scripture.

Love is patient, love is kind. It does not envy, it does not boast, it is not proud. It does not dishonor others, it is not self-seeking, it is not easily angered, it keeps no record of wrongs. Love does not delight in evil but rejoices with the truth. It always protects, always trusts, always hopes, always perseveres. Love never fails. — I Corinthians 13.4-8 NIV

Our idols aren’t patient or kind; they aren’t self-giving or forgiving. Our idols demand subservience at all costs—especially the loss of our humanity.

The pastoral mission of John of Patmos is to inspire the imaginations of God’s people—to place before them the vision of the Lamb Who Was Slain—the only One worthy to reign in heaven—because he is the embodiment of self-giving love. The Lamb moves us to worship not because of some ‘shock and awe’ display of brute force. No, the Lamb moves us to worship because the self-giving love of God smites our hearts with a power that could never be possessed by tanks or bombs. The image of God being restored in God’s redeemed people is the vocation of serving as priestly rulers on God’s behalf, reflecting God’s loving reign into the world God loves.

The questions with which John of Patmos confronts us are of allegiance and trajectory.

What vision of ‘the good life’ is forming the desires of our hearts—the shape and aim of our lives—through the everyday practices in which we often unconsciously participate?

__________________

Michael J. Gorman, Reading Revelation Responsibly: Uncivil Worship and Witness Following the Lamb Into the New Creation (Cascade Books, 2011), p.139.

N. T. Wright, Revelation For Everyone (Westminster John Knox, 2011), p.92.

April 25, 2016

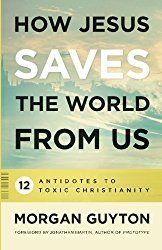

Prophetic Detox: A Review of Morgan Guyton’s book How Jesus Saves the World From Us

Morgan Guyton is a husband, father, writer, Methodist campus minister serving the students of Tulane and Loyola in New Orleans, and he also might be the inventor of the “rave sermon” [1]. I’ve been reading his blog, Mercy Not Sacrifice, for many years and a few years ago we took a run at starting an online collective of writers called “The Despised Ones”. Over all the years I’ve known Morgan, he has challenged and encouraged my thinking with both pastoral and prophetic wisdom. And he continues to do so with his first book, How Jesus Saves the World From Us.

In this book, Morgan takes on 12 of the most toxic aspects of Christianity in the U.S., which include, but aren’t limited to: performance, biblicism, separatism, judgment, and hierarchical power. While Morgan clearly approaches these subjects from firmly within the “progressive” wing of Christianity in the U.S., I was pleasantly surprised at just what an equal opportunity offender he was. There’s no doubt in my mind some of Morgan’s criticisms will not be well-received by his own progressive comrades.

In this book, Morgan takes on 12 of the most toxic aspects of Christianity in the U.S., which include, but aren’t limited to: performance, biblicism, separatism, judgment, and hierarchical power. While Morgan clearly approaches these subjects from firmly within the “progressive” wing of Christianity in the U.S., I was pleasantly surprised at just what an equal opportunity offender he was. There’s no doubt in my mind some of Morgan’s criticisms will not be well-received by his own progressive comrades.

For example, I remember when we were co-leading “The Despised Ones,” it was understood that anyone and everyone was welcome. That’s progressive Christianity 101, after all! Well, that didn’t last long. Even progressives have their own “unclean” communities: “abusers” and “unsafe” persons, are just a couple examples. So, quickly the discussion in our group shifted from how inclusive we were of anyone and everyone, to how there was no hope of redemption for “oppressors.” And few recognized the irony. That’s why I thought it was wonderful to read this passage in Morgan’s book:

“Jesus’ meal with Zacchaeus committed the cardinal sin of today’s progressive activist culture: centering the oppressor. Did Jesus betray everyone who had been oppressed by Zacchaeus by eating dinner with him? What would Twitter say? […]

The goal of Jesus’ solidarity with all sinners and victims of their sin is to dismantle our divisions so that all humanity can be reconciled together.” (p.116-117)

This will definitely offend Morgan’s progressive friends who will no doubt accuse him of revictimizing them. But Morgan demonstrates that he’s not interested in toeing any theological camp’s “party line.” He’s perfectly willing to call attention to the hypocrisy of both the Right and the Left! For this courage, I applaud him.

But that certainly doesn’t mean Morgan is unwilling to boldly confront the ubiquitous abuses of the conservative, Fundamentalist Right in the U.S.. He most assuredly does that. However, unlike other progressive Christian authors who have practically made this style of writing into its own genre, I think Morgan critiques this favored target with more pastoral sensitivity and personal reflection than usual. Morgan is nothing if not first self-critical. He locates himself directly within the demographic most often responsible for abuses of power, racial insensitivity, denigration of women, etc. Part of Morgan’s genius is using his own highly reflective journey as a guide for others who share his social location. He doesn’t stand outside and hurl stones at white, cis-gendered, straight males—he stands within that space and calls attention to his own failings and how he’s seen God’s grace transform him. This might actually be the only Christ-like way to challenge people who are like you in so many ways, but nevertheless hold a significantly divergent worldview. Two of my favorite chapters were “Worship Not Performance” and “Poetry Not Math.”

Redeeming Justification

In “Worship Not Performance,” Morgan reframes the essential human problem from guilt to self-consciousness. I think this is brilliant. Today, in the U.S., when I hear sermons or read writing that calls attention to God’s power to forgive the guilty, I hear chirping crickets. I’m not sure I ever felt “guilty” for my sins, and that certainly wasn’t what turned my heart toward God. Instead, I was chiefly aware of my alienation from God, from others, and even from myself. I felt like I was wearing a mask all the time, trying to live up to a mysterious and often shifting set of expectations. And I always felt like there was a gap between who I knew I was and who I was for other people. Self-consciousness is a better description of that experience than “guilt.”

White Westerners like “guilt” as a descriptor of sin because they like to conceptualize God as a judge who wants law and order above all. When you’re on top of the world in terms of political power and wealth, it’s to your benefit to conceptualize God as a “law and order” God. It keeps the riff-raff in check. But, if, as Morgan puts it, we have been “transformed from curious delightful worshippers into anxious, self-obsessed performers,” (p.8) then everyone on any spectrum of political power or wealth is implicated. In fact, the most “anxious” and “self-obsessed” people might be those who “break commandments” the least. Those who are most “anxious” and “self-obsessed” might even be those who are very religious and very wealthy. Such a reframe is not advantageous to the rich and powerful. It necessarily levels the sin playing field. And that’s precisely why I think it’s such a brilliant and biblical reconceptualization. Here’s a little taste to whet your appetite:

“We are not saved from God’s disapproval. We are saved from the self-isolation of believing the serpent’s lie and hiding in the bushes from God. Faith isn’t the performance that passes God’s test to earn us a ticket to heaven; it’s the abolition of performance that liberates us from the hell of self-justification and restores us to a life of authentic worship.” (p.17)

Another reason I love this chapter so much, is that it rescues the doctrine of “justification by grace through faith” from those who peddle it as a replacement for sanctification. There is a wealthy and politically powerful contingent of American Christians who love, love, love them some “justification by grace through faith” because it promises to free them from the “legalism” of “works.” What then happens is, “the Gospel” is equated with a message that we “don’t have to do anything to earn our salvation,” and everyone who already didn’t want to “do anything” erupts in joy. But Morgan’s reframe on this cherished Protestant doctrine actually ups the ante. There is nothing more challenging than to daily resist the pressure to self-justify and to perform for the expectations of others, or even ourselves. This take on justification by grace through faith actually requires me to daily relinquish my own nagging need for status, recognition, and value to God as a “work” that is far more strenuous than following some list of “dos and don’ts”. This reframe of justification makes sanctification essential rather than dismissing it as an optional addition to the Christian life. And that’s a message Christians in the U.S. desperately need to hear.

Deepening Hermeneutics

In “Poetry Not Math,” Morgan takes aim at toxic hermeneutics in a beautifully-brief yet powerfully-poignant chapter. So much of my own journey of faith has included grappling with biblical interpretation. I was incredibly impressed by how succinctly Morgan captured concepts it has taken me over a decade to work through thoughtfully. (Where was this book when I was 17?!)

By describing our relationship to biblical interpretation as more akin to one with poetry than one with math, Morgan takes the legs out from underneath those who would accuse him of undervaluing the Bible. Poetry is not “less valuable” than math. In fact, viewed one way, poetry may be more valuable than math, since math has very defined limits, while poetry is potentially limitless. Also, by comparing our interpretation of Scripture to interpretation of poetry, Morgan sneakily teaches a post-colonial and post-modern hermeneutic. Who we are has as much to do with our interpretations of the Bible as the text itself. Again, this is a message the church in the U.S. desperately needs to hear.

For far too long, Fundamentalists in particular, but also many, if not most, conservative evangelicals, have put forth a conception of Scripture that is little more than a facade behind which they hide their own bids for wealth and political power. The certainty with which they’ve spoken about what is an “abomination” to God and the certainty with which they’ve spoken about the divine purpose of geo-political events could only be supported by a “mathematical” conception of Scripture. To admit that hermeneutics is more of an art than a science would be to admit that they could be wrong, and that just wouldn’t be good for fundraising nor fear-mongering. And that’s why this chapter is so necessary. Here’s another sample:

“Poetry has a unique truth about it. Arguments that you might lose in logic can be won through poetry. It does justice to realities that cannot be captured by scientific explanation. It gets under your skin in a way that strictly rational communication cannot. Most importantly, good poetry is never finished being interpreted. No one can say the final word on a good poem, because its meaning defies any conclusive explanation.” (p.70)

As a pastor in a highly diverse congregation, I am routinely faced with questions about biblical interpretation from every possible starting point. Morgan’s take on biblical interpretation is one that will aid me immensely as I lead both Fundamentalists and progressives toward a more faithful immersion in the biblical narrative.

Conclusion

How Jesus Saves the World from Us is a gift to the church. In particular, it is a gift to those who, like Morgan, are open to God’s leading of them on a journey of exploration, adventure, and delight. This book is not for those who are so confident in their own views that they do not want to have them challenged. Reviews from those folks have already been predictably defensive. Rather, this book is for those who are humble or want to be humble. This book is for those who want to peer into the life of a Christian writer in the U.S. as he processes with depth and wisdom several of the most challenging subjects of the Christian life. As for me, I’ll be revisiting and recommending this book often. And I’m tremendously grateful to Morgan for writing it.

_______________________

1. Jonathan Martin, who wrote the forward to How Jesus Saves the World from Us was the preacher behind whose sermon Morgan performed his modified “progressive trance” music.

March 21, 2016

Palm Sunday: Two “Triumphs”

Palm Sunday is the occasion on the Christian calendar when we commemorate Jesus’s “triumphal entry” in Jerusalem. The concept of a triumph requires some explanation because it’s foreign to modern Americans.

A triumph was a ceremonial and celebratory procession through the streets of a city. When the Romans wanted to celebrate their latest conquest, they celebrated with a triumph. In fact, in 70AD the Roman general Titus destroyed the very city into which Jesus entered that first Palm Sunday. Titus’s triumph, with the spoils from the Jerusalem Temple, is depicted on a monument which remains to this day in Rome.

That first Palm Sunday, Jesus wasn’t the only person leading a procession into Jerusalem. There was a second. From the opposite side of the city, Pontius Pilate was entering Jerusalem from his home in Caesarea. His procession was in the Roman style—complete with a terrifying display of Rome’s military might. Pilate was perched atop a majestic stallion with all the trappings of Roman wealth and prestige. His procession was a proclamation of his and Rome’s superiority. The message was directed to the pilgrims who had gathered in the city from near and far for the Passover festivities. “Don’t let things get out of control. Or these soldiers you see here, they will cut you down!” (1)

That first Palm Sunday, Jesus wasn’t the only person leading a procession into Jerusalem. There was a second. From the opposite side of the city, Pontius Pilate was entering Jerusalem from his home in Caesarea. His procession was in the Roman style—complete with a terrifying display of Rome’s military might. Pilate was perched atop a majestic stallion with all the trappings of Roman wealth and prestige. His procession was a proclamation of his and Rome’s superiority. The message was directed to the pilgrims who had gathered in the city from near and far for the Passover festivities. “Don’t let things get out of control. Or these soldiers you see here, they will cut you down!” (1)

But Jesus’s “triumph” was of an altogether different kind. His victory would not be won by military might. His status would not secured by wealth or prestige. And he isn’t interested in asserting his superiority. By direct contrast, Jesus enters Jerusalem in humility, on a donkey.

Mark’s Gospel makes it clear Jesus deliberately staged his “triumphal entry” to fulfill the prophesy of Zechariah:

“Rejoice greatly, Daughter Zion! Shout, Daughter Jerusalem! See, your king comes to you, righteous and victorious, lowly and riding on a donkey, on a colt, the foal of a donkey.” (9.9)

Jesus sent his disciples to bring him a donkey colt for him to ride. Jesus staged his procession as a prophetic lampoon of Roman imperial pomp and circumstance. He meant it to expose the pretensions that exalt themselves.

When my children were a little smaller than they are now, I used to read them stories from this book called Donkeys and Kings by Tripp York. He tells eight Bible stories from the perspectives of the animals in the stories. But the star of the book is the story of Jesus entering Jerusalem on a donkey. In this story, the donkey Jesus rode into the city, George, finds himself stabled with the royal horses of the Caesar’s court. And they are not happy at all at the ruckus his rider has caused. In fact, they’re outraged at his presumptuousness to be in a procession at all. Here’s what the arrogant royal stallion, named Constantine, says to George, the donkey Jesus rode into Jerusalem:

When my children were a little smaller than they are now, I used to read them stories from this book called Donkeys and Kings by Tripp York. He tells eight Bible stories from the perspectives of the animals in the stories. But the star of the book is the story of Jesus entering Jerusalem on a donkey. In this story, the donkey Jesus rode into the city, George, finds himself stabled with the royal horses of the Caesar’s court. And they are not happy at all at the ruckus his rider has caused. In fact, they’re outraged at his presumptuousness to be in a procession at all. Here’s what the arrogant royal stallion, named Constantine, says to George, the donkey Jesus rode into Jerusalem:

“…your kind does not get to make history. History is made by the strong, the powerful—those in charge. It si made by kings, Caesars, warriors, government officials, nobility, and stallions. It is not made by the weak, the lowly, those filled with resentment for their small and insignificant place in life. It is not made by creatures like you or the one you gave a ride into the city.” (2)

Today we celebrate Jesus’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem because it reveals to us an altogether different way of being-in-the-world from the arrogance and violence of empires.

In Luke’s account, when Jesus sees the city of Jerusalem he foresees its destruction in 70 AD and he weeps over the city. He said,

“Would that you, Jerusalem, had known on this day the things that make for peace! But now they are hidden from your eyes.” (Lk. 19.42 ESV)

May we not make the same mistake. May we see the way of Jesus and his way of peace!

Responsive Reading:

One: Hosanna! Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord! Today we celebrate the triumphal entry into Jerusalem of our King, Jesus!

All: Hosanna! Hosanna! Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord!

One: Humble, riding on a donkey, King Jesus entered the city as the crowds prepared the way for his victorious arrival.

All: Rejoice! Rejoice! The triumphant King has come!

One: On the journey to liberation from sin, we celebrate Christ’s victory, we sorrowfully contemplate his sacrifice, and we revel in his resurrection.

All: We remember the long road to freedom that our ancestors traveled, filled with triumphs, death, and new life.

One: Ride on, King Jesus! Ride on, conquering King!

All: Jesus came “to bring Good News to the poor; to proclaim release to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind; and to set the oppressed free.” (Lk. 4.18)

One: With excitement and joy we welcome you into our lives. With loud shouts of hosanna we joy you on your march toward liberation, justice, and love for all people.

All: Rejoice! Rejoice! The triumphant King has come! (3)

Prayer:

We praise you, O God,

For your redemption of the world through Jesus Christ.

Today he entered the holy city of Jerusalem in triumph

and was proclaimed Messiah and King,

by those who spread garments and branches along his way.

Let these branches be signs of his victory,

and grant that we who carry them

may follow him in the way of the Cross,

that, dying and rising with him, we may enter into your Kingdom;

Through Jesus Christ, who lives and reigns

with you and the Holy Spirit, now and forever.

Amen. (4)

______________________

Marcus Borg, “Holy Week: Two Different Meanings” [http://www.marcusjborg.com/2011/05/07/holy-week-two-different-meanings]

Tripp York, Donkeys and Kings: And Other “Tails” of the Bible, p. 43 [http://astore.amazon.com/theolograffi-20/detail/1606089404]

Adapted from “Triumphant Entry (Palm Sunday)” Litany in African American Heritage Hymnal,

p.66.

Adapted from the Book of Common Worship, “Palm Sunday”.

February 17, 2016

Treasures in the Attic: A Brief Review of Water to Wine by Brian Zahnd

In Mark 2.22, Jesus said,

And no one pours new wine into old wineskins. Otherwise, the wine will burst the skins, and both the wine and the wineskins will be ruined. No, they pour new wine into new wineskins.

I’m no wine aficionado, but I think it’s common knowledge that wine gets better with age. Maybe there is something about the aging process that brings out the wine’s flavor and texture. But Jesus is clearly doing a new thing among the people in Judea. He teaches with authority, unlike the scribes and Pharisees. He takes authority over demons, heals people of their diseases, and even commands the wind and waves. Jesus welcomes sinners to his table and forgives people of their sins. This is “new wine” indeed! So, people need renewed thinking to understand what God is doing in and through Jesus. They need new “wineskins.”

But, what if you’re not a first-century Judean witnessing the ministry of Jesus firsthand? What if you’re a twenty-first century Westerner who has been immersed in an Americanized form of Christianity that looks very little like the faith of Jesus. Well, in that event, the “old” wineskins of an ancient faith might feel quite “new” to you. And, in fact, many Christians today are discovering just that. They are discovering for the first time what Christianity has been for hundreds of years and to them it tastes as rich as aged wine.

In Water to Wine, pastor Zahnd tells “some of [his] story” around cultivating a richer Christian faith. But this journey hasn’t let Zahnd to some novel form of Christianity. No, it has led Zahnd to recover much of what has characterized Christian faith since the time of the early church. Water to Wine is about an American evangelical pastor who had been successful at being an American evangelical, but not at being a faithful Christian. The beauty and power of Water to Wine is seeing snapshots of Zahnd rediscovering Christianity like a man who finds priceless treasures in his own attic.

One way of reading Water to Wine is to see in it a prophetic indictment of Americanized Christianity. Another way is to read it as an invitation into a journey that Zahnd and many others have embarked upon. It’s a journey for those Christians who have grown dissatisfied with grape juice Christianity, are craving “new wine,” and are discovering it in “old wineskins.”

Potter’s Wheel Prayer

One of the most profound transitions Zahnd has underwent is out of consumer Christianity and into the Spiritual Formation movement made popular by authors and thinkers like Dallas Willard and Eugene Peterson. In “Jerusalem Bells,” Zahnd recounts how God began to teach him how, after being a pastor for several decades, to finally pray well. It was similar to a movement I’ve described as going from wielding prayer like a tool, to viewing prayer as a potter’s wheel on which one is being formed. At first, Zahnd is annoyed by the Muslim call to prayer he hears in Middle Eastern countries in which he’s led pilgrims. But God’s Spirit uses this occasion of discomfort to lead Zahnd into the ancient practice of formative prayer. This was one of my favorite sections of the book. Like Zahnd, formative prayer has breathed new life into my Christian faith. It has caused me to rely more on God and to situate myself in the global and historic body of Christ. I love what Zahnd says here,

“If we think of prayer as ‘just talking to God’ and that it consists mostly in asking God to do this or that, then we don’t need to be given prayers to pray. Just tell God what we want. But if prayer is spiritual formation and not God-management, then we cannot depend on our self to pray properly. If we trust our self to pray, we just end up recycling our own issues—mostly anger and anxiety—without experiencing any transformation. We pray in circles. We pray and stay put. We pray prayers that begin and end in our own little self. When it comes to spiritual formation, we are what we pray. Without wise input that comes from outside ourselves, we will never change. We will just keep praying what we already are. A selfish person prays selfish prayers. An angry person prays angry prayers. A greedy person prays greedy prayers. A manipulative person prays manipulative prayers. Nothing changes. We make no progress. But it’s worse than that. Not only do we not make progress, we actually harden our heart. To consistently pray in a wrong way reinforces a wrong spiritual formation.” (p.75)

Due to this insight, Zahnd has now made teaching Jesus-disciples how to be properly formed in prayer a pillar of his ministry. He regularly teaches a “prayer school” at Word of Life, the church he leads as pastor and he says it’s the best thing he does as a pastor. Even though he staunchly refuses to bottle up his teaching on prayer and sell it or give it away in video form online, he nevertheless includes a central component of his prayer insight in Water to Wine. “Jerusalem Bells” concludes with a morning liturgy of prayer Zahnd himself uses and teaches others to use. It’s a wonderful collection of Psalms, prayers from the Book of Common Prayer, passages of Scripture, and prayers from a wide variety of Christian traditions. When one prays this liturgy, she can be assured she is being properly formed.

A Journey into Maturity

Overall, Water to Wine is about growing up in the faith. It’s about being weaned off milk and learning to eat meat. Many American Christians have been taught that milk is all there is, or that milk is actually the stuff of maturity. But Zahnd exposes the immaturity of consumeristic, militaristic, tribalist, dualistic, and secular Christianity. And instead of merely replacing them with an equal and opposite list of -isms, Zahnd invites readers into an experiential practice of discipleship that is rooted in the global and historic church. Zahnd’s gift is helping readers taste the richness of a Christianity that’s been aged to maturity through his eyes of wonder and joy as he discovers it anew. His pastoral gift comes through as he invites us to join him on his journey.

This is a wonderful and timely little book that I would recommend to just about anyone. For many it will rekindle a faith that has laid dormant. For others it will kick open the doors to new rooms of Christianity that haven’t yet been explored. For others still, this may be the best introduction to Christianity they’ve ever read. For all who read it, it offers a fascinating glimpse at the spirituality of an American Christianity that is discovering treasures in the attic of the church.

_______________