T.C. Moore's Blog, page 2

May 4, 2022

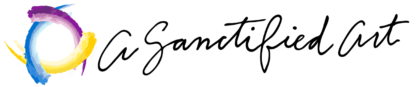

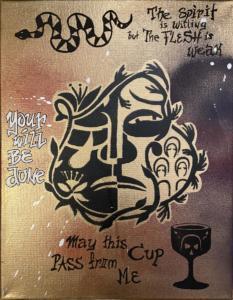

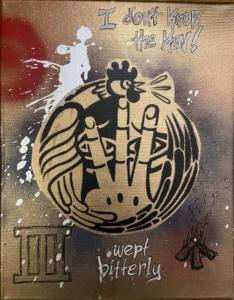

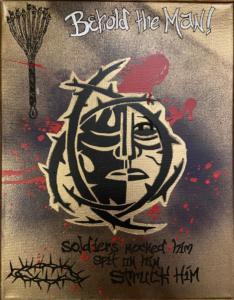

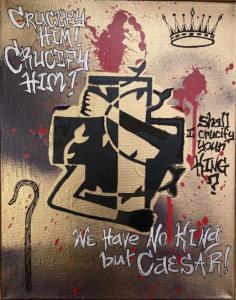

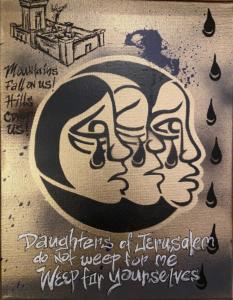

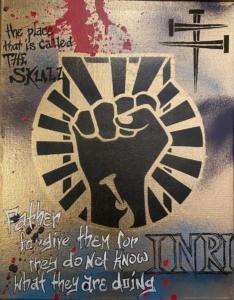

Graffiti Stations of the Cross

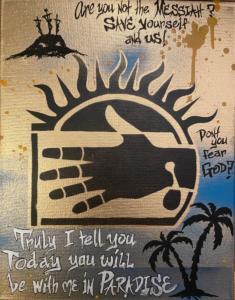

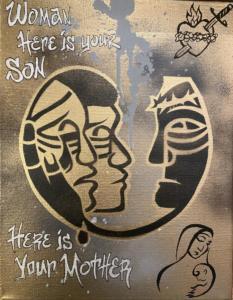

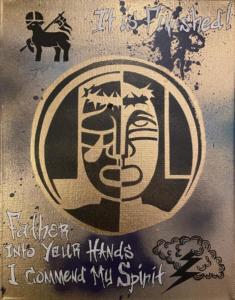

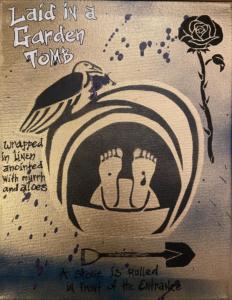

For Good Friday this year, I took on my most ambitious painting project to date: Graffiti Stations of the Cross.

The Stations of the Cross is a tradition going back hundreds of years that makes it possible for a worshiper to walk in the footsteps of Jesus to the cross without a costly journey to the Holy Land. Through artistic depictions of the Gospel accounts, worshippers can pray and meditate upon each “station” as they follow Jesus to the cross. I love that this tradition makes it possible for those who may lack the resources necessary to physically visit Jerusalem to nevertheless connect with the crucified Christ.

The Stations of the Cross is a tradition going back hundreds of years that makes it possible for a worshiper to walk in the footsteps of Jesus to the cross without a costly journey to the Holy Land. Through artistic depictions of the Gospel accounts, worshippers can pray and meditate upon each “station” as they follow Jesus to the cross. I love that this tradition makes it possible for those who may lack the resources necessary to physically visit Jerusalem to nevertheless connect with the crucified Christ.

For me, it was important to express the stations through the lens of graffiti, which is another way of delivering this tradition to a non-traditional audience. Graffiti has been known as “the voice of the streets,” and it’s an essential element of hip hop culture—a multiethnic cultural movement birthed in New York. In bringing the pilgrimage to the people through the tradition of the Stations, and through the utilization of a pop art medium like graffiti, my goal was to make our Good Friday meditations upon the cross accessible to all.

For me, it was important to express the stations through the lens of graffiti, which is another way of delivering this tradition to a non-traditional audience. Graffiti has been known as “the voice of the streets,” and it’s an essential element of hip hop culture—a multiethnic cultural movement birthed in New York. In bringing the pilgrimage to the people through the tradition of the Stations, and through the utilization of a pop art medium like graffiti, my goal was to make our Good Friday meditations upon the cross accessible to all.

My Stations were inspired by the bold graphic symbols created by Lauren Wright Pittman, from A Sanctified Art. She created the twelve symbols in the center of each piece, and they reflect a sensitivity to the emotional journey to the cross, as well as an emphasis on the role of women in the story. Another artist whose stark and beautiful designs inspired me is Scott Erickson. His graphically designed Stations in the Street contain powerful imagery, some of which I incorporated. Huge thanks to these fantastic artists for their inspirational works.

Below is a gallery of the twelve paintings I created. Once you select a thumbnail, a dialogue box with directional arrows will guide you through the rest of the images.

#bwg_container1_3 #bwg_container2_3 .bwg-container-3.bwg-standard-thumbnails { width: 904px; justify-content: center; margin:0 auto !important; background-color: rgba(255, 255, 255, 0.00); padding-left: 4px; padding-top: 4px; max-width: 100%; } #bwg_container1_3 #bwg_container2_3 .bwg-container-3.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-item { justify-content: flex-start; max-width: 180px; width: 180px !important; } #bwg_container1_3 #bwg_container2_3 .bwg-container-3.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-item > a { margin-right: 4px; margin-bottom: 4px; } #bwg_container1_3 #bwg_container2_3 .bwg-container-3.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-item0 { padding: 0px; background-color:rgba(0,0,0, 0.30); border: 0px none #CCCCCC; opacity: 1.00; border-radius: 0; box-shadow: ; } #bwg_container1_3 #bwg_container2_3 .bwg-container-3.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-item1 img { max-height: none; max-width: none; padding: 0 !important; } @media only screen and (min-width: 480px) { #bwg_container1_3 #bwg_container2_3 .bwg-container-3.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-item1 img { -webkit-transition: all .3s; transition: all .3s; } #bwg_container1_3 #bwg_container2_3 .bwg-container-3.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-item1 img:hover { -ms-transform: scale(1.08); -webkit-transform: scale(1.08); transform: scale(1.08); } } #bwg_container1_3 #bwg_container2_3 .bwg-container-3.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-item1 { padding-top: 50%; } #bwg_container1_3 #bwg_container2_3 .bwg-container-3.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-title2, #bwg_container1_3 #bwg_container2_3 .bwg-container-3.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-ecommerce2 { color: #323A45; font-family: Ubuntu; font-size: 16px; font-weight: bold; padding: 2px; text-shadow: ; max-height: 100%; } #bwg_container1_3 #bwg_container2_3 .bwg-container-3.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-thumb-description span { color: #323A45; font-family: Ubuntu; font-size: 12px; max-height: 100%; word-wrap: break-word; } #bwg_container1_3 #bwg_container2_3 .bwg-container-3.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-play-icon2 { font-size: 32px; } #bwg_container1_3 #bwg_container2_3 .bwg-container-3.bwg-standard-thumbnails .bwg-ecommerce2 { font-size: 19.2px; color: #323A45; }

/*pagination styles*/ #bwg_container1_3 #bwg_container2_3 .tablenav-pages_3 { text-align: center; font-size: 12px; font-family: Ubuntu; font-weight: bold; color: #666666; margin: 6px 0 4px; display: block; } @media only screen and (max-width : 320px) { #bwg_container1_3 #bwg_container2_3 .displaying-num_3 { display: none; } } #bwg_container1_3 #bwg_container2_3 .displaying-num_3 { font-size: 12px; font-family: Ubuntu; font-weight: bold; color: #666666; margin-right: 10px; vertical-align: middle; } #bwg_container1_3 #bwg_container2_3 .paging-input_3 { font-size: 12px; font-family: Ubuntu; font-weight: bold; color: #666666; vertical-align: middle; } #bwg_container1_3 #bwg_container2_3 .tablenav-pages_3 a.disabled, #bwg_container1_3 #bwg_container2_3 .tablenav-pages_3 a.disabled:hover, #bwg_container1_3 #bwg_container2_3 .tablenav-pages_3 a.disabled:focus, #bwg_container1_3 #bwg_container2_3 .tablenav-pages_3 input.bwg_current_page { cursor: default; color: rgba(102, 102, 102, 0.5); } #bwg_container1_3 #bwg_container2_3 .tablenav-pages_3 a, #bwg_container1_3 #bwg_container2_3 .tablenav-pages_3 input.bwg_current_page { cursor: pointer; text-align: center; font-size: 12px; font-family: Ubuntu; font-weight: bold; color: #666666; text-decoration: none; padding: 3px 6px; margin: 0; border-radius: 0; border-style: solid; border-width: 1px; border-color: #E3E3E3; background-color: #FFFFFF; opacity: 1.00; box-shadow: 0; transition: all 0.3s ease 0s;-webkit-transition: all 0.3s ease 0s; } if( jQuery('.bwg_nav_cont_3').length > 1 ) { jQuery('.bwg_nav_cont_3').first().remove() } function spider_page_3(cur, x, y, load_more) { if (typeof load_more == "undefined") { var load_more = false; } if (jQuery(cur).hasClass('disabled')) { return false; } var items_county_3 = 1; switch (y) { case 1: if (x >= items_county_3) { document.getElementById('page_number_3').value = items_county_3; } else { document.getElementById('page_number_3').value = x + 1; } break; case 2: document.getElementById('page_number_3').value = items_county_3; break; case -1: if (x == 1) { document.getElementById('page_number_3').value = 1; } else { document.getElementById('page_number_3').value = x - 1; } break; case -2: document.getElementById('page_number_3').value = 1; break; case 0: document.getElementById('page_number_3').value = x; break; default: document.getElementById('page_number_3').value = 1; } bwg_ajax('gal_front_form_3', '3', 'bwg_thumbnails_3', '0', '', 'gallery', 0, '', '', load_more, '', 1); } jQuery('.first-page-3').on('click', function () { spider_page_3(this, 1, -2, 'numeric'); return false; }); jQuery('.prev-page-3').on('click', function () { spider_page_3(this, 1, -1, 'numeric'); return false; }); jQuery('.next-page-3').on('click', function () { spider_page_3(this, 1, 1, 'numeric'); return false; }); jQuery('.last-page-3').on('click', function () { spider_page_3(this, 1, 2, 'numeric'); return false; }); /* Change page on input enter. */ function bwg_change_page_3( e, that ) { if ( e.key == 'Enter' ) { var to_page = parseInt(jQuery(that).val()); var pages_count = jQuery(that).parents(".pagination-links").data("pages-count"); var current_url_param = jQuery(that).attr('data-url-info'); if (to_page > pages_count) { to_page = 1; } spider_page_3(this, to_page, 0, 'numeric'); return false; } return true; } jQuery('.bwg_load_btn_3').on('click', function () { spider_page_3(this, 1, 1, true); return false; }); #bwg_container1_3 #bwg_container2_3 #spider_popup_overlay_3 { background-color: #EEEEEE; opacity: 0.60; } if (document.readyState === 'complete') { if( typeof bwg_main_ready == 'function' ) { if ( jQuery("#bwg_container1_3").height() ) { bwg_main_ready(jQuery("#bwg_container1_3")); } } } else { document.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', function() { if( typeof bwg_main_ready == 'function' ) { if ( jQuery("#bwg_container1_3").height() ) { bwg_main_ready(jQuery("#bwg_container1_3")); } } }); }

/*pagination styles*/ #bwg_container1_3 #bwg_container2_3 .tablenav-pages_3 { text-align: center; font-size: 12px; font-family: Ubuntu; font-weight: bold; color: #666666; margin: 6px 0 4px; display: block; } @media only screen and (max-width : 320px) { #bwg_container1_3 #bwg_container2_3 .displaying-num_3 { display: none; } } #bwg_container1_3 #bwg_container2_3 .displaying-num_3 { font-size: 12px; font-family: Ubuntu; font-weight: bold; color: #666666; margin-right: 10px; vertical-align: middle; } #bwg_container1_3 #bwg_container2_3 .paging-input_3 { font-size: 12px; font-family: Ubuntu; font-weight: bold; color: #666666; vertical-align: middle; } #bwg_container1_3 #bwg_container2_3 .tablenav-pages_3 a.disabled, #bwg_container1_3 #bwg_container2_3 .tablenav-pages_3 a.disabled:hover, #bwg_container1_3 #bwg_container2_3 .tablenav-pages_3 a.disabled:focus, #bwg_container1_3 #bwg_container2_3 .tablenav-pages_3 input.bwg_current_page { cursor: default; color: rgba(102, 102, 102, 0.5); } #bwg_container1_3 #bwg_container2_3 .tablenav-pages_3 a, #bwg_container1_3 #bwg_container2_3 .tablenav-pages_3 input.bwg_current_page { cursor: pointer; text-align: center; font-size: 12px; font-family: Ubuntu; font-weight: bold; color: #666666; text-decoration: none; padding: 3px 6px; margin: 0; border-radius: 0; border-style: solid; border-width: 1px; border-color: #E3E3E3; background-color: #FFFFFF; opacity: 1.00; box-shadow: 0; transition: all 0.3s ease 0s;-webkit-transition: all 0.3s ease 0s; } if( jQuery('.bwg_nav_cont_3').length > 1 ) { jQuery('.bwg_nav_cont_3').first().remove() } function spider_page_3(cur, x, y, load_more) { if (typeof load_more == "undefined") { var load_more = false; } if (jQuery(cur).hasClass('disabled')) { return false; } var items_county_3 = 1; switch (y) { case 1: if (x >= items_county_3) { document.getElementById('page_number_3').value = items_county_3; } else { document.getElementById('page_number_3').value = x + 1; } break; case 2: document.getElementById('page_number_3').value = items_county_3; break; case -1: if (x == 1) { document.getElementById('page_number_3').value = 1; } else { document.getElementById('page_number_3').value = x - 1; } break; case -2: document.getElementById('page_number_3').value = 1; break; case 0: document.getElementById('page_number_3').value = x; break; default: document.getElementById('page_number_3').value = 1; } bwg_ajax('gal_front_form_3', '3', 'bwg_thumbnails_3', '0', '', 'gallery', 0, '', '', load_more, '', 1); } jQuery('.first-page-3').on('click', function () { spider_page_3(this, 1, -2, 'numeric'); return false; }); jQuery('.prev-page-3').on('click', function () { spider_page_3(this, 1, -1, 'numeric'); return false; }); jQuery('.next-page-3').on('click', function () { spider_page_3(this, 1, 1, 'numeric'); return false; }); jQuery('.last-page-3').on('click', function () { spider_page_3(this, 1, 2, 'numeric'); return false; }); /* Change page on input enter. */ function bwg_change_page_3( e, that ) { if ( e.key == 'Enter' ) { var to_page = parseInt(jQuery(that).val()); var pages_count = jQuery(that).parents(".pagination-links").data("pages-count"); var current_url_param = jQuery(that).attr('data-url-info'); if (to_page > pages_count) { to_page = 1; } spider_page_3(this, to_page, 0, 'numeric'); return false; } return true; } jQuery('.bwg_load_btn_3').on('click', function () { spider_page_3(this, 1, 1, true); return false; }); #bwg_container1_3 #bwg_container2_3 #spider_popup_overlay_3 { background-color: #EEEEEE; opacity: 0.60; } if (document.readyState === 'complete') { if( typeof bwg_main_ready == 'function' ) { if ( jQuery("#bwg_container1_3").height() ) { bwg_main_ready(jQuery("#bwg_container1_3")); } } } else { document.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', function() { if( typeof bwg_main_ready == 'function' ) { if ( jQuery("#bwg_container1_3").height() ) { bwg_main_ready(jQuery("#bwg_container1_3")); } } }); }

December 21, 2021

My Top Ten Books of 2021

Continuing my annual tradition, here’s my 2021 book list. These are the top 10 books I read this year with recommendations, reviews, and even a video interview with one of the authors.

1. Reading While Black by Esau McCaulleyReading While Black was the first book I read in 2021 and it was the best. Dr. McCaulley expertly introduces the uninitiated to the ecclesial Black tradition of biblical interpretation and distinguishes it from other traditions. In so doing, he masterfully demonstrates the prophetic relevance of the scriptures for activism and social justice. This is a must read!

Check out my extended video review!

2. What is God’s Kingdom and What Does Citizenship Look Like? by César GarcíaWhile What is God’s Kingdom may have been the shortest book I read this year, it’s among the best. From now on it’ll be my go-to book on the subject. Even though it’s concise, it doesn’t fail to be impactful. García brilliantly communicates an Anabaptist ethic that avoids the common pitfalls of White Neo-Anabaptists. Namely, he doesn’t allow the distinction of the church to lead to separatism and political quietism. Instead, he explicates a missional ecclesiology that engages the polis for the common good. This too is a must read!

Check out my review over at Missio Alliance!

3. How to Have an Enemy by Melissa Florer-BixlerAs a Mennonite pastor, Florer-Bixler has no doubt had to contend with all the typical stereotypes about “peacemaking.” In this book, she explodes all the most toxic caricatures. How to Have an Enemy argues that enmity is distinct from difference and while difference can be tolerated, even celebrated, enmity is based on unjust power differentials. To love our enemies, we fight to dismantle the unjust systems that produce enmity. If you’re someone who thinks that dialogue is a silver bullet to cure every problem facing the church, you will hate this book. But if you’ve read the Gospels and fallen in love with the radical prophet who sparks a movement that turns the world upside down, you will love this book. It’s the most thought-provoking book I read all year, and it’s a must read!

4. Subversive Witness by Dominique GilliardDominique has done it again. His sophomore offering is as good or better than his first release. This time he’s tackling another thorny subject. Not the prison industrial complex or penal substitutionary atonement; this time it’s Privilege. Many have no doubt asked Dominique, “So what do I do with my privilege?” This book is the answer. And not only does he answer this question using all his experience as a pastor and expertise as an antiracist trainer, Dominique also expertly mines the scriptures for their wisdom and provides an interpretive lens that illuminates the role privilege plays. This is an excellent resource that I highly recommend!

5. Caste by Isabel WilkersonAt 496 pages, Caste was definitely the longest book I read this year, but it was well worth it. Isabel Wilkerson, well known for her other bestselling book, The Warmth of Other Suns, offers a new and expertly-researched theory: America has a caste system. I’ll admit, at first, I didn’t get it. I was confused as to what value this theory adds to the pantheon of antiracist work already in circulation. But, by the end, I was sold. Caste provides a necessary lens through which to see the United States’ relationship to race, class, and gender. This is an eye-opening book and I highly recommend it.

6. Struggling with Evangelicalism by Dan StringerSince 2016, Evangelicalism has been desperately embattled. Many question whether it’s even redeemable. Dan Stringer doesn’t answer the question of whether any particular person should remain an evangelical. That’s for you to decide. Instead, he brings new insights to bear. One example is not approaching “evangelicalism” as a Brand one can identify with or not (like Pepsi or Apple), but instead as a cultural Space we inhabit. Many who are now disavowing the brand nevertheless continue to occupy the space. So rather than helping people to discern whether to call oneself an evangelical, Dan helps readers understand what evangelicalism is, what its done wrong, but also its strengths. He doesn’t attempt to persuade anyone to “stay”; he simply offers this guide to people who are struggling. It’s a great book that, for some, is very needed!

Check out my video interview with Dan!

7. Welcoming the Stranger by Matthew Sorens and Jenny YangWelcoming the Stranger is the most in-depth book I’ve ever read on immigration and I’m so glad I did. While it’s very well researched, it doesn’t get bogged down. Instead, the authors keep the reader’s attention with vivid stories of real people’s lives. It’s also blunt about the partisan political realities. Everyone who reads this book will be better informed. This is an excellent resource that everyone needs on their shelf.

8. Why is There Suffering? by Bethany SollerederWhy is There Suffering? is the most creative book I read this year. This isn’t your typical “Choose Your Own Adventure” book. No, this book guides readers through theological, philosophical, and ethical choices in order to assist readers at arriving at their own conclusions about the so-called “problem of evil.” This format is nothing short of brilliant! I wish I’d had this book when I was a teenager. I wouldn’t have had to read the dozens of other books I read in this subject. I highly recommend this unique book!

9. Taking America Back for God by Andrew Whitehead and Samuel PerryTaking America Back for God explodes the media narrative that “evangelicals” or even “white evangelicals” got Donald Trump elected. It’s not that simple, says the data. Instead, what Whitehead and Perry demonstrate is that Christian Nationalism got Donald Trump elected. In fact, the data also shows that the more religious a person is, the less likely they were to support Trump. This book is mind-blowing. I’m so glad I read this book, because it helps me understand people who were a complete mystery to me. I highly recommend this book!

10. Who Will Be a Witness? by Drew HartThe last book I read this year is one of my favorites, from one of my favorite authors. Drew Hart doesn’t just write a book that delves deeply into the theological and political realities of following Jesus—but he does that too! He’s also written a book that mobilizes the church to be part of what God is already up to in the world. Too often books about what the church can do for justice don’t acknowledge that the Spirit is out ahead of the church, drawing us further and further into God’s Kingdom. Drew’s book not only acknowledges this—he illuminates this truth in accessible and persuasive ways. Readers will love and remember Drew’s vivid analogies. Leaders will love that the book has a free study guide. Churches will love the practical guidance. This is a must-read for churches seeking the shalom of their cities.

September 13, 2021

How to Check Your Privilege: A Review of Subversive Witness by Dominique Gilliard

Today in the U.S. a highly effective strategy has been implemented to stifle any attempt to teach about systemic racism and its impact on society. A handful of conservative partisan operatives have turned the phrase “Critical Race Theory” (which is the name of an academic legal theory that’s been taught in law schools for decades) into a catch-all category for any subject related to racism that makes recalcitrant White Americans uncomfortable. The ramifications have been wide-spread and destructive. School board meetings have turned into battlefields, with White residents feeling emboldened to denounce concepts they don’t understand and to ‘cancel’ any teacher willing to teach them. Partisan politicians have also seized upon this strategy and wielded it like a bludgeon to pummel anyone speaking out against racial injustice. And the strategy to scapegoat “Critical Race Theory” is an intentionally deceptive strategy, as one of its architects candidly admits:

One of the subjects that’s been lumped into this pro-racism campaign because it makes White Americans nervous is privilege. The subject of privilege has a way of cutting to the heart of discussions about racial injustice by pinpointing the place where systemic racism hits home in our everyday lives. Privilege is often the presenting symptom of racial injustice. It’s the place where hidden norms, unspoken rules, and policy hidden in legalese comes to light. Unjust outcomes betray the injustice that was ‘baked into the cake.’ But privilege isn’t only a bugaboo for racists; privilege is also often a frustrating conundrum even for those who care deeply about redressing social injustices. It raises the important question: What can be done if a person has privilege but doesn’t want to unjustly benefit from it? Even for many anti-racists, the topic of privilege can feel overwhelming, which can lead to fatigue and even apathy.

That’s why Dominique Gilliard’s new book Subversive Witness: Scripture’s Call to Leverage Privilege is such an important and timely resource. Gilliard confronts the reality of privilege head-on with laser focus. He doesn’t mince words in this book and he draws upon the wisdom of Scripture and the best scholarship available. He parses out what privilege is and isn’t, and also what can be done with it.

Having privilege is not a sin, though sin has perverted our systems and structures in ways that engender sinful disparities. Privilege creates and expands anti-gospel inequities that infringe on collective liberation and shalom. It endows a few with educational, socioeconomic, political, vocational, and other advantages while disenfranchising many—simply because of how God intentionally created them. (p.13)

One of the ways Gilliard unpacks the concept of privilege is through a theological reading of Scripture, by supplying biblical commentary on stories and characters with which/whom are already very familiar, but adding the lens of privilege. He retells the story of the Hebrew midwives, Esther, Moses, Paul & Silas, Jesus, and Zacchaeus. But in retelling these stories, we are now given lens through which we can recognize how privilege works and what to do with it.

For example, Gilliard retells the very familiar story of Moses, but homes in on the cultural and ethnic dynamics at play when a Hebrew boy is raised in the Egyptian royal court. He narrates the ways Moses’s story illustrates solidarity and the leveraging of privilege for the sake of faithfulness to God and God’s people. Gilliard highlights a type of privilege we may not immediately recognize in the story: education privilege. Moses’s story of living in Midian for several decades and learning from his father-in-law, Jethro, can be viewed as an example of education privilege. It mirrors the experience of many Americans who have had the opportunity to leave (or escape) unhealthy environments and receive training and knowledge in a much safer and more supportive space. Gilliard challenges readers to consider how one might utilize such privilege. Will a person merely use their education to advance their own career, or will they use that know-how to reinvest back in the communities that need help?

In fact, over and over, Gilliard demonstrates that throughout the Scriptures, God has been calling people to leverage the advantages they’ve been afforded for the sake of others, rather than exploiting those advantages for selfish gain. This is perhaps the core message of Subversive Witness. Being a disciples of Jesus means learning from Jesus and becoming more like him. And Jesus didn’t exploit his privilege, he leveraged it for the sake of others. This is precisely what the apostle Paul writes in the famous ‘Christ hymn’ of Philippians:

Who, though he was in the form of God, did not regard equality with God as something to be exploited, but emptied himself, taking the form of a slave, being born in human likeness. And being found in human form, he humbled himself and became obedient to the point of death—even death on a cross. (NRSV, emphasis mine)

Few passages articulate Jesus’ ethic of sacrificial love as comprehensively as the Christ hymn (vv. 6-11). When we take on the mindset of Christ, we do nothing out of selfish ambition or conceit and refrain from exploiting our status and positions for selfish gain. We also, in humility, empty ourselves for the sake of the kingdom and our neighbors. This entails standing in solidarity with our neighbors when we have the option not to, placing the interests of others before our own, and prioritizing the peace and prosperity of our communities above our individual success—knowing that Scripture assures us that when our communities prosper, we do as well. In taking this Christlike posture, we move toward a collectivist pursuit of freedom, flourishing, and shalom. (p.104)

I loved Gilliard’s critique of American ‘rugged individualism’ in this book. This has been an emphasis of my own pastoral teaching ministry for many years now, and it was heartening to read him highlighting it as well. I wish more pastors—particularly White Evangelicals (and even some who consider themselves ‘Progressive’)—understood this.

In addition to racial injustice, the U.S. is also plagued by COVID-19. And if the last 18 months have revealed anything, it’s that there’s no bottom to the individualistic self-centeredness of many millions of Americans. Gilliard’s message of leveraging rather than exploiting privilege is precisely what millions of Americans who have prioritized their own comfort and partisan politics before the health and safety of their entire community by refusing to be vaccinated need to hear. Political freedom in this country is a privilege, and many who claim to be Christians are exploiting their freedom rather than leveraging it in the service of others. That’s not the Jesus Way.

I also think Gilliard demonstrates his own teaching on leveraging privilege in the book itself. He’s had the privilege of learning from some of the most brilliant thinkers and experienced experts in the fields pertinent to this topic. But rather than merely repackaging their insights as his own, he draws readers’ attention toward this diverse array of scholars and practitioners. For example, he tells the story of Jonathan “Pastah J” Brooks, who’s work in the Englewood neighborhood of Chicago has helped to transform that community. And Gilliard points us to so many other important voices like Willie James Jennings, Justo González, Brenda Salter McNeil, and Bryan Stevenson. This is another way of leveraging privilege—by sharing not only the insight one has gained, but also the sources from which we draw it.

In Subversive Witness, Dominique Gilliard weaves together wisdom from Scripture on privilege with insights from some of today’s leading thinkers and practitioners. Those who are humble enough to accept this wisdom will move further into living the Jesus Way and will be more equipped to partner with God in bringing shalom to our churches, communities, and world. I highly recommend this book.

March 22, 2021

On N. T. Wright, the Cross, and Systemic Racism

Some who are attracted to N. T. Wright’s theology and affirm much of it nevertheless also deny the existence of systemic racism—something Wright acknowledges. They aren’t entirely to blame for this contradiction, since Wright has written surprisingly little on the subject. However, Wright has been explicit about his theology of the “principalities and powers” and their defeat on the cross of Jesus. This theme is actually quite central to Wright’s theology. For example, in The Day the Revolution Began he clearly connects the defeat of the powers on the cross with the overthrow of evil that is systemically present in society—systemic evil that includes racism. Therefore, it is accurate to say that N. T. Wright’s theology entails an essential acknowledgement and renunciation of systemic racism, regardless of how disappointing that may be to some of his most ardent, albeit confused, supporters.

Wright’s Theology of the CrossIn The Day the Revolution Began, Wright critiques the popular portrayal of what is often called the “Penal Substitution” theory of the atonement. It may even be fair to say he critiques the core idea of it. Here’s a brief but sufficient sampling:

“You cannot rescue someone from the scars of an abusive upbringing by replaying the same narrative on a cosmic scale and mouthing the words ‘love’ as you do.” (p.44)

“In most popular Christianity, ‘heaven’ (and ‘fellowship with God’ in the present) is the goal, and ‘sin’ (bad behavior, deserving punishment) is the problem. A Platonized goal and a moralizing diagnosis—and together they led, as I have been suggesting, to a paganize ‘solution’ in which an angry divinity is pacified by human sacrifice.” (p.74)

“Doubtless [Paul] was aware of the non-Jewish meanings of someone ‘dying for’ someone else or for some cause, and doubtless he was aware of the dangers of saying what had to be said in such a way as to give credence to the idea of a detached, capricious, or malevolent divinity demanding blood, longing to kill someone, and happening to light upon a convenient innocent victim.” (p.232)

“This is why I have said that the real danger in expounding the meaning of Jesus’s death is to collapse it into a kind of pagan scenario in which an angry God is pacified by taking out his wrath on Jesus.” (p.257)

Instead of the very pagan idea of angry gods being pacified by venting their wrath upon an innocent human victim as a blood sacrifice, Wright’s theology of the cross necessarily entails Jesus’s paradigmatic conflict with the rulers and powers demonstrated throughout the story of the Gospel told by Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, and retold by Paul and the other apostles. He writes,

“We have already heard the cryptic hint in 1 Corinthians 2:8, where the ‘rulers’ wouldn’t have executed Jesus if they had understood who he was and what the result would be. Here [in Colossians 2.13-15] the point is spelled out far more graphically. If we ask Paul what had happened when Jesus died—if we bring to him our question of what had changed by six o’clock on that evening, what was different about the world, what was now true that hadn’t been true twenty-four hours earlier—I think this is one of the primary things he would have said, that the rulers, the powers, had been defeated. When Paul speaks of the ‘rulers and authorities,’ he means both the visible rulers, the Herods, the Caesars, the governors, and the priests, and the ‘invisible’ rulers, the dark powers that stand behind them and operate through them. By the time Jesus’s body was taken down from the cross, Paul believed, these ‘rulers and authorities’ had been stripped, shamed, and defeated.” (p.258-259)

For Wright there are two ‘dimensions’ so to speak of the enemies who opposed Jesus and over whom Jesus triumphed through the Cross and Resurrection. These two dimensions are the “visible” and the “invisible.” The visible enemies are the literal governors, officials, religious leaders, and military figures who oversee the social systems of the world. Examples are plentiful but three figures loom large in the narrative of the Gospel. Herod is a ruler who represents the power of wealth and corrupt economic systems. Meanwhile Caiaphas (the High Priest) represents the corrupt religious system. And, thirdly, Pontius Pilate represents the corrupt military empire of Rome. These three rulers and powers who normally were at odds with each other, conspire together against their shared enemy: Jesus.

Behind these visible rulers and powers, Wright teaches us, lurk dark forces of evil that “operate through them.” Chief among these dark forces is the one called “the satan.” This week’s Gospel reading is from John chapter 12, in which Jesus says this world must have its “ruler” cast out. John is telling a story that culminates in Jesus’s showdown with the satan (ha satan), which means the accuser. We can see this, for example, in how John tells the story of Judas’s betrayal. John says the satan entered Judas:

“The satan, the accuser, has already put it into Judas’s heart to betray Jesus (13.2). Judas will be the accuser’s mouthpiece, embodying and enacting the great accusation, the anti-God, anticreation, antihuman force at large in the world.” (p.412)

To sum up where we are so far: For N. T. Wright, Jesus’s Cross is an essential part of the Gospel story being told in the New Testament. However, Wright bluntly critiques popular notions of the meaning of Jesus’s Cross as “pagan”—particular portrayals that center around the idea of an angry God demanding the blood sacrifice of an innocent human victim. Instead, Wright sees in the New Testament a theology of the Cross that necessarily entails the defeat of the ‘rulers’ and ‘powers.’ These rulers and powers are both the visible governors, officials, and leaders as well as the invisible, dark powers of evil that operate through visible rulers. For Wright these dark forces are “anticreation” and “antihuman.”

The Defeat of the Power of RacismFor N. T. Wright, the evil forces that operate through visible rulers are often expressed in idolatrous ideologies and oppressive systems of power. He writes,

“…when there are forces at work in our world dealing in death and destruction, propagating dangerous ideologies without regard for those in the way, or forces that squash the poor to the ground and allow a tiny number to heap up wealth and power, we know we are dealing with Pharaoh once more. Idols are being worshipped, and they are demanding human sacrifices. But we know that on the cross the ultimate Pharaoh was defeated.” (p.378)

We don’t have to guess at what examples Wright might give of these oppressive forces at work in our world, because that’s the subject of the next chapter, the conclusion of the book. Here he details some historical systems of oppression the cross defeats, which point to present-day ones.

“What might it mean for the church today to live by the same belief? It would mean recognizing, for a start, that the ‘powers,’ though defeated on the cross, are still capable of enslaving millions. When we in the Western world think of forces that enslave millions we tend to think of the ideologies of the twentieth century, not least Communism, which until 1989 had half the world in its grip and still controls millions. Many in southern Africa think back to the terrible days of apartheid and remember with a shudder how racial segregation and the denial of basic freedoms to much of the nonwhite population were given an apparent Christian justification. Similar reflections continue to be appropriate in parts of the United States, where the victories won by the civil rights movement in the 1960s still sometimes appear more precarious than people had thought.

[…]Those of us who remember the 1970s will recall that commentators predicted, as a matter of certainty, a major civil war in South Africa. That this did not happen was largely due to that patient, prayerful struggle. Similar things might be said about the work of Martin Luther King, Jr., and many others in America, speaking with a powerful Christian voice that refused to be drowned out by the Ku Klux Klan, on the one hand , or the militant Black Power activists, on the other. These things have happened in my lifetime, and they are neither to be discounted nor explained away as the inevitable progress of enlightened liberal values in the modern world. As we should know, there is nothing inevitable about such things. What we witnessed was the power of the cross to snatch power from the enslaving idols.” (p.392-393)

Let’s recap once again, just so no one misses it. For N. T. Wright, Jesus’s cross is necessarily about the defeat of the ‘rulers’ and ‘powers’ that have both ‘visible’ and ‘invisible’ dimensions. The visible dimension are the governors, the officials, and the leaders who represent social systems. The invisible dimension are the forces of evil that operate through them—forces which Wright describes as “anticreation” and “antihuman.” Oppressive systems that “squash the poor to the ground and allow a tiny number to heap up wealth and power” are demonic and defeated by Jesus’s cross.

When Wright looks for historical examples of how the cross defeats these powers, he finds several that are racist social systems. He points to the apartheid system of racism in South Africa and he points to the White Supremacy system of racism in America. He credits leaders like Desmond Tutu and Martin Luther King, Jr. as prophetic Christian voices who lived out the belief that the powers are defeated by Jesus’s cross through their protests and movements for social change.

The only conclusion that can be drawn from this evidence is that for N. T. Wright the meaning of Jesus’s cross directly translates into opposition to systemic racism in societies like the United States. For N. T. Wright political organizing against “antihuman” systems is an essential part of our role as Christians.

“As Christians, our role in society is not to wring our hands at the corruption of power or simply to pick a candidate that supports one or another supposedly Christian policy. The Christian role, as part of naming the name of the crucified and risen Jesus on territory presently occupied by idols, is to speak the truth to power and especially to speak up for those with no power at all.

I have seen this again and again, mostly in cases that never make the newspapers but significantly transformed actual communities. I saw it when friends working in the prison system, some of them as chaplains, were able to go to the prison governors and point out ways in which the system was failing to protect many highly vulnerable young people in their care. I saw it when a small group managed to protest successfully on behalf of a man who had fled for his life from another country at a time when the government was keen to boost its statistics for keeping such people out.

[…]A central part of our vocation is, prayerfully and thoughtfully, to remind people with power, both official (government ministers) and unofficial (backstreet bullies), that there is a different way to be human. A true way. The Jesus way. This doesn’t mean ‘electing into office someone who shares our political agenda’; that might or might not be appropriate. It means being prepared, whoever the current officials are, to do what Jesus did with Pontius Pilate: confront them with a different vision of kingdom, truth, and power.” (p.400-401)

This blunt acknowledgement of the existence and evil of systemic racism will no doubt trouble those who are attracted to Wright’s theology but deny the reality of systemic racism. Nevertheless, it is a fact that not only does Wright acknowledge this reality, his theology of systemic racism’s defeat by Jesus’s cross as an instance of demonic power is an essential aspect of this view of the Christian Gospel and the church’s mission in the world.

February 15, 2021

New YouTube Channel!

Welcome to Theological Graffiti, a channel about life, faith, and the city. I’m T. C. and I’m a Jesus-disciple who has been transformed by the power of the Holy Spirit through the Gospel. For the last 20 years, I’ve served the multiethnic Jesus movement across the country from New Orleans to Boston to LA to the Twin Cities. In addition to mentoring court-involved teens, I also pastor a local church, write, and make videos here on YouTube. A crucial part of our journeys of faith is being theologically equipped to live out the Way of Jesus. That’s where this channel comes in. On this channel, I not only share my own reflections, I also point you to some of my favorite theology resources, and interview important theologians and urban ministers I think you’re going to love hearing from. So whether you’re a theology nerd like me, or just theology curious, this channel is here to encourage you, resource you, and challenge you to dig deeper.

December 21, 2020

21-Book Salute (2020)

Every year I set a reading goal. This year, my goal was two books per month. I fell slightly short with 21. But given that this year was 2020, and therefore awful, I feel good about it—especially considering how good the books were!

In order of when I read them:

[image error] (Affiliate link)[image error]1. Divine Impassibility: Four Views of God’s Emotions and SufferingEdited by Robert J. Matz and A. Chadwick Thornhill; Contributions by Daniel Costelo, James Dolezal, Thomas Jay Oord, and John PeckhamIf you’re at all familiar with my theological proclivities, you’re probably aware that I’ve read and written quite a bit on the subject of divine impassibility. For most, this probably seems like a strange obsession. I get that. But it’s also a critical component of one’s view of God. On it hinges the kind of God one worships. And, personally, I couldn’t worship an impassible god. That’s why the subject matters to me. This book offers four perspectives on divine impassibilty, but that’s a bit misleading. Only one of the four actually believes God is impassible. The other three either affirm God’s passibility outright or in some modified way that still ends up affirming it. Also, the one view which affirms divine impassibility specifically denies that the doctrine is derived from Scripture. For those for whom biblical grounding for one’s theology is important, impassibility is a non-starter.

[image error] (Affiliate link)[image error]2. Evangelical Theologies of Liberation and JusticeEdited by Mae Elise Cannon and Andrea SmithAt a time when “Evangelical” has become synonymous with right-wing “Conservative” partisan politics, and a White faction in the Southern Baptist Convention has declared war any teaching that calls out systemic racism, a book like this is vitally important. Those who are called “Evangelicals” in 2020 are not the Neo-Evangelicals of Post-war America who rejected Fundamentalism and embraced science, social activism, and racial integration. (Ask the Veggie Tales guy!) Evangelicals like those who founded Gordon-Conwell’s Center for Urban Ministerial Education (CUME)—my alma mater—have always embraced a holistic gospel that encompasses liberation and justice. Which is why chapter 10: “Leaning in to Liberating Love” about the birth of CUME was one of my favorite chapters. If you’ve been taught that Evangelicalism is what Al Mohler, Robert Jeffress, and Franklin Graham say it is, you need to read this book!

[image error] (Affiliate link)[image error]3. Four Views on Hell: Second Edition (2016)General Editor: Preston Sprinkle ; Series Editor: Stanley Gundry; Contributions by Denny Burk, John Stackhouse Jr., Robin Parry, and Jerry WallsBack at the start of the year, I was teaching a series on “Deconstruction” at the church where I serve as a pastor and wanted to bone up on the hell debate. It’d been so long since I’d gone through my own deconstruction and reconstruction process around “afterlife” beliefs (2000—2003) that I’d forgotten a lot of what informed my thinking. Thankfully, Zondervan had updated their “four views” book on this subject since the version I read back in Bible college and it was very helpful.

[image error] (Affiliate link)[image error]4. Razing Hell: Rethinking Everything You’ve Been Taught About God’s Wrath and JudgmentBy Sharon L. BakerFor that same teaching series, I also read this wonderful book. Unlike the Four Views book, Baker is pastoral in her approach to this subject—and also approaches it from a distinctly Peace Church perspective, which I appreciated. Two of places where Baker shined brightest was on the subjects of “Sheol” and “Gehenna.” I highly recommend this book for those interested in looking more deeply into what the Bible teaches about “hell.”

[image error] (Affiliate link)[image error]5. Womanist Sass and Talk Back: Social (In)Justice, Intersectionality, and Biblical InterpretationBy Mitzi J. SmithIt was a goal of mine to read more Womanism this year and this book felt like a good place to start. I’d recommend it to others who are dipping their toes in the Womanism pond. Each chapter is a bite-sized essay on an interesting subject. It’s more academic than might be comfortable for the casual theology reader. But for those who are at least somewhat theologically trained, this book will excite. I expect to read much more from Mitzi Smith in the future.

[image error] (Affiliate link)[image error]6. What is the Trinity and Why Does it Matter?By Steve DancauseI’m a big fan of Herald Press’s “The Jesus Way: Small Books of Radical Faith” series of books. I’ve already reviewed Dr. Dennis Edwards’ contribution: What is the Bible and How Do We Understand It? I think these very brief books are excellent introductions for lay persons. So I was excited to read the two latest contributions. Neither disappointed. Dancause does an excellent job presenting such a complex and rich subject in a winsome and meaningful way.

[image error] (Affiliate link)[image error]7. Why Do We Suffer and Where is God When We Do?By Valerie G. RempelTackling perhaps the most challenging question of them all—the question of suffering—is tremendously difficult when one has all the room required. But to do so in a format as brief as this series is a truly amazing feat. Rempel does a fantastic job. This is such an important subject—one that is so often mishandled and yet so crucial—I’d go so far as to say this should be required reading in churches.

[image error] (Affiliate link)[image error]8. Unsettling Truths: The Ongoing, Dehumanizing Legacy of the Doctrine of DiscoveryBy Mark Charles and Soong-Chan RahI’ve been waiting for this book to come out for years. Dr. Rah is a friend, mentor, and was one of my professors at CUME. Also, back when I was pastoring in LA, I met with Mark Charles and he told me about what he was working on: the Doctrine of Discovery. I was enthralled. It would be another three years before I’d have the book in my hands. But it was well worth the wait. This book not only walks readers through the long and horrific history of Settler Colonialism, it also introduces readers to a novel theory about White Fragility and trauma. Here’s an excerpt from my review:

“Unsettling Truths isn’t just a book, it’s a prophecy. It is a blazing spotlight focused directly on the darkness that plagues the United States, and in particular white, North American Christians. It calls us out of the darkness of historical ignorance and into the light of moral courage. It calls us out of the darkness of White Supremacy and into the light of antiracism and ethnic conciliation. It calls us out of the darkness of American Empire and into the light of the global body of Christ. ‘Sunlight is the best disinfectant.’ ”

[image error] (Affiliate link)[image error]9. Resilient Faith: How the Early Christian “Third Way” Changed the WorldBy Gerald L. SittserWhat attracted me to this book was the phrase “Third Way” in the title. I’m very pleased that Sittser didn’t use this phrase to Bothsides partisan politics or to commit the “Middle Ground” logical fallacy. Instead, he details the historical roots of the term and its import for today. Here’s an excerpt from my review:

“Resilient Faith fits well into a sub-genre of books that have proliferated in the U.S. within the last several decades, which are designed to help the church adapt to ‘Post-Christian’ or ‘Post-Christendom’ society. While Sittser certainly isn’t the first non-Anabaptist Christian author to also recognize the unholy marriage of church and state as a significant ‘shift’ in not only the history of the West, but also in the church’s theology and practice, he nevertheless connects those dots in a way that didn’t feel like a ‘How To’ book. I appreciated this a lot since I’ve grown weary of the hundreds of ‘Missional’ books that all seem to sound the same. Yet Sittser isn’t entire non-prescriptive. He does see the early church’s example as a model for how the modern church can continue to faithfully witness to the Kingdom of God.”

Check out my review [image error]

[image error] (Affiliate link)[image error]10. The God Who Trusts: A Relational Theology of Divine Faith, Hope, and LoveBy Wm. Curtis HoltzenI met Curtis Holtzen in 2013 at an Open Theism conference I was co-directing in Saint Paul. Later we reconnected in Southern California while I was pastoring out there. He’s a gifted professor with keen cultural insights. That’s why I was so excited to read this book. Here’s an excerpt from my review:

“In The God Who Trusts, Curtis Holtzen demonstrates a vast knowledge of his subject. He traverses the thought of Aquinas and Tillich, process theologians and Reformed. He uses vivid analogies that stick with readers and at times his words catch the homiletical tenor of a preacher. It’s a good read! And with the publishing of The God Who Trusts, Holtzen joins the hallowed ranks of brave and brilliant theologians who have written monographs in the Open and Relational theological movement. His comrades are figures like Clark Pinnock, John Sanders, Bill Hasker, Richard Rice, David Basinger, Thomas Jay Oord, and Greg Boyd. But The God Who Trusts strikes a very different tone and emphasis from these other works—filling what I now can see was a significant void.”

[image error] (Affiliate link)[image error]11. A Multitude of All Peoples: Engaging Ancient Christianity’s Global IdentityBy Vince BantuVince Bantu and I go way back to our seminary days in Boston at CUME and we’ve kept in touch over the years since. Vince has become one of the country’s leading scholars of early African Christianities and he’s incredibly good at communicating his research to audiences. While this book is no ‘beach read,’ it was thrilling for this theology nerd, since I’m often perplexed and frustrated by what Soong-Chan Rah calls the “Western White Captivity of the Church.” Here’s an excerpt from my review:

“Along with the detailed history of the Gospel’s early spread to Africa, the rest of the Middle East, and Asia, [A Multitude of All Peoples] also problematizes the notion of ‘orthodoxy’ that has come to dominate, especially in modern American Evangelical circles. What is taken for granted by the vast majority of Western Christians is that there is a clear and decisive history of orthodox theology going back to Nicea and Chalcedon. But like the whitewashed history of Christian missions, this too is a narrative warped by Euro-American ethnocentrism and White Supremacy. The reality is far more complex.”

[image error] (Affiliate links)[image error]12. Might from the Margins: The Gospel’s Power to Turn the Tables on InjusticeBy Dennis EdwardsDennis Edwards is a beloved mentor and inspiration. While his primary work is in the academy these days, he’s an incredibly gifted pastor as well. The pastoral insights are what makes this book stand out from the rest. Here’s an excerpt from my review:

“Might From the Margins draws our attention to the way power factors into our understanding of the Christian faith. Power is something that White Evangelicals in particular have a difficult time talking about. It’s something that makes them/us uncomfortable. Which is precisely why White Evangelicals need to read this book.”

[image error] (Affiliate link)[image error]13. Bonhoeffer’s Black Jesus: Harlem Renaissance Theology and an Ethic of ResistanceBy Reggie WilliamsThis year, leading up to the presidential election, I noticed many churches beginning teaching series on how to “dialogue” and heard a lot of Bothsidesing coming from White Evangelical pulpits. That’s why, instead, I chose to teach on the life and legacy of Dietrich Bonhoeffer. His fight against Fascism in 1930s Germany was more instructive for how Jesus-disciples should position ourselves relative to the U.S. government pre-election. Reggie Williams’ excellent book on Bonhoeffer’s transformative experience in Harlem was a primary text as I prepared sermons.

Check out this sermon called “From Volk to Spoke”

[image error] (Affiliate link)[image error]14. Three Views on Eastern Orthodoxy and Evangelicalism (Counterpoints)General Editor: James Stamoolis ; Series Editor: Stanley Gundry; Contributions by Bradley Nassif, Michael Horton, Vladimir Berzonsky, George Hancock-Stefan, and Edward RommenFrom time to time, I’m impressed by the far less dualistic, more organic theological foundations in Eastern Orthodoxy. And yet, the tradition is not without its own foibles. After being alerted to a sale by an online bookstore on the Counterpoints series, I picked up a few books including this gem. I found it very helpful.

[image error] (Affiliate link)[image error]15. The Spiritual Danger of Donald Trump: 30 Evangelical Christians on Justice, Truth, and Moral IntegrityEdited by Ron Sider; Contributions by Ron Sider, Mark Galli, Miroslav Volf, Stephen Haynes, and John Fea (among others)In 2020, many media outlets continually portrayed “Evangelicals” as a Conservative/Republican monolith, which is of course far from true. In reality, there was a vocal and sustained resistance to the toxicity of Trumpism resounding in the corridors of many Evangelical institutions. For example, Mark Galli was famously ousted from his role as Editor of Christianity Today for his pointed criticism of Donald Trump and the immorality and corruption he represents. He and many others contributed to this important book.

[image error] (Affiliate link)[image error]16. God and the Pandemic: A Christian Reflection on the Coronavirus and Its AftermathBy N. T. WrightIt’s nothing short of amazing how prolific is N. T. Wright. He somehow managed to write a book about the global pandemic while most of us were still reeling from it. This book is very brief—particularly by Wright’s book-length standards—but power-packed.

[image error] (Affiliate link)[image error]17. Jesus and the DisinheritedBy Howard ThurmanAt some point in 2020 I realized that I desperately needed to read Jesus and the Disinherited. This work lays a foundation for so many of the works I’ve been reading and yet remains highly relevant today. Even though it was written over half a century ago, some of the insights could not have been more prescient. I am confident this is a book I will need to read again and again for years to come.

[image error] (Affiliate link)[image error]18. Jesus According to the New TestamentBy James D. G. DunnOccasionally I want to sink my teeth into some New Testament studies that remind me of my early Bible college and seminary days. This year, we lost one of the greats. James (known affectionally by his friends as “Jimmy”) Dunn was a giant of New Testament scholarship. And yet his writing style is without pretense and entirely approachable to intermediate to even beginning scholars. This book is no exception.

[image error] (Affiliate link)[image error]19. Strange Glory: A Life of Dietrich BonhoefferBy Charles Marsh

In my studies of Bonhoeffer for the teaching/preaching series I led for our congregation, I wanted to read something that more directly reflected upon Bonhoeffer’s early childhood and background. I learned a ton from this book that I never would have imagined about the way Bonhoeffer was raised. This book was filled with immense details and yet also a feast for the imagination. A must-read for those who want to understand who Bonhoeffer was.

[image error] (Affiliate link)[image error]20. The Battle for Bonhoeffer: Debating Discipleship in the Age of TrumpBy Stephen HaynesI primarily wanted to read this book because of how the Bonhoeffer biography written by Conservative Trump-supporter Eric Metaxes has so proliferated the market and monopolized the popular perception of Bonhoeffer among Conservative White Evangelicals. This book shows precisely why the portrait painted by Metaxes is self-serving and drastically skewed.

[image error] (Affiliate link)[image error]21. Broken Signposts: How Christianity Makes Sense of the WorldBy N. T. WrightYes, I read two books by Wright this year. (That’s not a record! Some years I read several books by Wright). It just so happens that this book was sent to me from HarperCollins before it was officially released (which was thrilling!) and so I couldn’t resist. Despite being world-famous for his encyclopedic knowledge and insight into the person and work of the apostle Paul/Saul of Tarsus, this book is actually about the Fourth Gospel (aka “John”). I’m still hoping to give this book the review it deserves, but it will likely have to wait until 2021.

My 2021 Book Stack(Some I’ve Already Begun to Read)

There were several really good books that I started but wasn’t able to finish reading in 2020. They have already made it into my 2021 stack, and I’m excited to start digging in soon!

Links to Amazon for books in this post are “Affiliate” links. If you purchase a book using any of these links, I will receive a small commission.November 15, 2020

Busting 5 Peacemaking Myths

If you know anything about me, you probably know that peace is a big deal for me. You probably know that one of the Christian traditions that’s had an important influence on how I think about following Jesus is the Peace Church tradition of the Anabaptists. You probably also know that I advocate for nonviolence and you probably know my wife Osheta’s first book was even entitled Shalom Sistas. So, for some folks, it comes as somewhat of a shock when I weigh in on matters of social justice in politics. Some folks are surprised and dismayed when I call out racism, misogyny, or economic injustice. They sometimes accuse me of violating my own emphasis on peace. They might see me making comments or statements about public policy and ask “How does peacemaking fit into this?” This question betrays a fundamental misunderstanding about what biblical “peace” means—one that I once unfortunately had as well. But, thankfully, through study of the Scriptures, through learning from wise mentors and biblical scholars, and through my own advocacy with and for those who experience injustice, I’ve been disabused of many unbiblical ways of thinking about peace. And now it’s one of my favorite subjects.

So, in this piece, I’m going to be dispelling five common misconceptions about peacemaking while talking about what peacemaking in the Way of Jesus is really all about.

In the NIV, Matthew 5.1-12 reads:

Now when Jesus saw the crowds, he went up on a mountainside and sat down. His disciples came to him, and he began to teach them. He said: “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted. Blessed are the meek, for they will inherit the earth. Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they will be filled. Blessed are the merciful, for they will be shown mercy. Blessed are the pure in heart, for they will see God. Blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called children of God. Blessed are those who are persecuted because of righteousness, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. “Blessed are you when people insult you, persecute you and falsely say all kinds of evil against you because of me. Rejoice and be glad, because great is your reward in heaven, for in the same way they persecuted the prophets who were before you.

It’s possible that some of us are so familiar with these words that we have trouble hearing them anymore. For example, I’ve observed that many of us invest our own understanding of “peacemaking” into Jesus’s use of the term here. There was a time not all that long ago when I had unknowingly invested peacemaking with my own faulty assumptions. I confused Jesus’s way of peace-making with what I’d been taught, which was all about peace-keeping. So the first myth I’m going to bust is the myth that peace-making is the same as peace-keeping.

1. Peace-keeping isn’t Peace-makingFor starters, we tend to lightly skip over the connection between peacemaking and persecution right here in the Beatitudes. Jesus was a peacemaker and yet he was also persecuted. Jesus concludes the beatitudes with the fact that the prophets were also persecuted, so his disciples are in good company. Dietrich Bonhoeffer was a peacemaker too, and obviously he was persecuted. This is where people get stuck. How can a prophet also be a peacemaker?

The misconception is that prophetic speech, such as speaking up for the oppressed, calling out injustice, isn’t peaceful. Maybe it’s cold comfort that this isn’t just a modern-day misconception. People in Jesus’s day had this misunderstanding too. Here’s what Jesus says to address this misunderstanding in his day:

Do not think that I have come to bring peace to the earth. I have not come to bring peace, but a sword. For I have come to set a man against his father, and a daughter against her mother, and a daughter-in-law against her mother-in-law. And a person’s enemies will be those of his own household. (Matthew 10.34-36)

See, Jesus is differentiating his peace from a common misconception of peace: going along to get along. Jesus is saying his peace is also a sharp and poignant truth! And the truth divides. When we’ve committed to Jesus Christ, it may mean some folks won’t be on our side anymore. The truth that Jesus is the Messiah who brings God’s kingdom on earth as it is in heaven is a divisive truth. It’s good news to those who embrace Jesus as their king; it’s very bad news to those who reject him and his kingdom. It’s good news to those who look around at the world and recognize that it’s broken, unjust, in need of renewal. It’s bad news to those who have a vested interest in preserving the status quo from which they benefit.

Jesus teaches that the truth of his kingdom divides like a sword and that some who end up on the other side might be members of our own families. Nevertheless, Jesus calls for our allegiance. Once a wannabe disciple said he would follow Jesus after burying his father. Jesus’s response was, “Follow me, and let the dead bury their own dead.” (Mt. 8.22) Jesus was a peacemaker, and yet Jesus’s peace was confrontational and a lot of us don’t like confrontation. We would rather avoid it. Unfortunately conflict-avoidance isn’t peace-making. Here’s how Osheta puts it:

2. Avoiding Conflict isn’t Peacemaking“It’s been a year of embracing my calling as a peacemaker and owning the conviction that peacemaking is more than gentle words and a humble attitude to avoid conflict when prophetic words and righteous indignation burns hot in my chest. If I do all I can to avoid conflict, then I’m simply a peacekeeper, not a peacemaker. Sometimes I forget we’re not called to be peace-keepers—the children of God are made of sterner stuff than to merely keep the peace—no, Jesus challenges us to be peacemakers. The difference is subtle, but subversive. Peacekeeping maintains the unjust status quo by preferring the powerful. Peacemaking flips over a few tables and breaks out a whip when the poor are exploited. Peacekeeping does everything to secure a place at the table. Peacemaking says all are welcome to the table, then extends the table with leaves of inclusive love. Fear drives Peacekeeping. Love powers Peacemaking.”

Do you see how this mistaking of peace-making as peace-keeping is closely related to the myth that peacemaking is avoiding conflict? This might be a particular struggle for those of us who have been culturally conditioned to avoid conflict. Maybe you grew up in a family that “just didn’t talk about those things.” Or maybe you grew up with an abiding fear that if you rocked the boat or stepped out of line in any way, you’d lose everything. You could be shunned, you could become an outcast, you could lose the people who mean the most to you: your family. So, you learned to do everything in your power to avoid conflict.

This is like growing up in a home with an alcoholic or abusive family member and everyone in the family would rather keep silent about it than confront that person. There’s a strong belief that everything will be better if we just don’t upset that person. So, the disease or the abuse gets worse and worse. That’s not peace-making.

Jesus never shied away from confronting the social ills of his day. Jesus accused religious leaders who were considered holy and well-respected of being hypocrites who abused their power to prey upon vulnerable people. Mark 12.38-40 says,

As he taught, Jesus said, “Watch out for the teachers of the law. They like to walk around in flowing robes and be greeted with respect in the marketplaces, and have the most important seats in the synagogues and the places of honor at banquets. They devour widows’ houses and for a show make lengthy prayers. These men will be punished most severely.”

Or how about the woes Jesus pronounced upon the rich?

“But woe to you who are rich, for you have already received your comfort. Woe to you who are well fed now, for you will go hungry. Woe to you who laugh now, for you will mourn and weep. Woe to you when everyone speaks well of you, for that is how their ancestors treated the false prophets. (Luke 6.24-26)

Yikes! Calm down, Jesus! Someone is going to call you a Socialist! The idea that Jesus was ever “meek and mild” is some kind of weird modern domestication of his prophetic voice. Anyone who simply reads the Gospels can see that Jesus was anything but meek and mild.

3. Neutrality isn’t PeacemakingNot only do we sometimes mistakenly associate peacemaking with conflict avoidance, we also sometimes mistakenly associate Peacemaking with Neutrality. This mistake was a particularly attractive one for me. Neutrality can carry with it an air of superiority. It’s like that old analogy of people holding different parts of an elephant in the dark and trying to describe it. Each person is wrong because they only perceive one part of the elephant. The person who mistakes peacemaking for neutrality imagines themselves the objective observer who sees the entire elephant, unlike those poor souls stuck in the dark. What’s even more ironic is that this posture of neutrality is often described by its adherents as “humility” when in fact it’s the most arrogant position of all.

But when we follow Jesus, we end up in the places where Jesus ended up, with the people that Jesus end up with. And the more we love like Jesus loved, the more clearly we can see why Jesus identifies with those who society overlooks, the afflicted, the imprisoned, the disenfranchised. We realize that Jesus himself wasn’t neutral. He came to seek and save the last, the lost, and the least. He didn’t come for those who think they are well; he came for those who know they are sick.

Jesus is the Word incarnate, God in the flesh! And yet he came as a poor peasant member of a conquered and occupied people group. He lived his life on the margins of society not the seat of power. He didn’t have to die on a cross as a criminal, but that’s the life of love he chose. Dietrich Bonhoeffer grew up wealthy and privileged. He didn’t have to die in a Nazi concentration camp, but that’s the life of love he chose. The reason Bonhoeffer set aside his power and privilege to identify with the powerless is because he was a follower of Jesus.

Elie Wiesel was a survivor of one of those Nazi concentration camps that Bonhoeffer opposed. And Wiesel went on to become a prolific and awarded author. He once wrote this:

“I swore never to be silent whenever and wherever human beings endure suffering and humiliation. We must always take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.”

Peacemaking is messy and requires courage. We’re not called to sit on the sidelines or fade into the background. We’re not called to preserve the status quo or business as usual. We’re called to be peacemakers. Dr. King understood this too and once wrote:

4. Having No Boundaries isn’t Peacemaking“I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate… who prefers a negative peace (the absence of tension) to a positive peace (the presence of justice).”

But someone will say, “T. C., doesn’t peacemaking entail listening to one another and seeking to understand each other?” Of course! I think hearing one another’s stories is a vital part of peacemaking. When we hear one another’s stories, it can build our empathy for one another. We might find important common ground that helps up move toward one another. I see an example of this in the life of Jesus when he dialogued with the Pharisee named Nicodemus, who came to him at night. Jesus didn’t rebuke him as he regularly did the other Pharisees who publicly tried to trap him. No, he received Nicodemus and spoke with him directly yet graciousness. But there are a couple critically important caveats that need to be inserted here.

Peace-making doesn’t mean having no boundaries. It’s psychologically unhealthy for a person who has experienced significant trauma to continually subject themselves to re-traumatization. Our calling to be peacemakers doesn’t mean we have to constantly relive our trauma by listening to people who hold dehumanizing, toxic, or abusive positions. It’s not peacemaking to be a sponge for toxicity. It’s not peacemaking to be a doormat.

For example, this is particularly true for our sisters and brothers who are part of minority groups. It’s not being a peacemaker for them to be constantly subjected to the views of people who further stigmatize, stereotype, or denigrate their identities.

James Baldwin once wrote:

“We can disagree and still love each other unless your disagreement is rooted in my oppression and denial of my humanity and right to exist.”

For those who publicly propped up the oppressive power structure of his day, Jesus had only words of judgment. He publicly called them to repent or face the judgment of God. Don’t make the mistake of thinking that Jesus wasn’t a peacemaker because he was also a prophet! And don’t make the mistake of thinking that modern-day prophets aren’t also peacemakers, simply because they call the rulers and powers to repentance.

5. Bothsidesing isn’t PeacemakingSometimes this false dichotomy between peacemaking and the prophetic call to repentance leads people to the false notion that Peacemaking requires us to ignore facts and create false moral equivalencies. This is also known as Bothsidesing. The reality is that very often two sides of an issue are not equally right or wrong—one side is just wrong. And the compulsion to find “middle ground” can lead people to destroy peace rather than make it. Remember this: “Half way between truth and lie is still a lie.”

Isaac Asimov was a brilliant scientist and prolific writer who taught at Boston University. He once received a letter from an english literature student named John who wanted to school Asimov in science. The letter-writer objected to Asimov’s assertion that modern science had made important advancements into understanding the nature of the universe over previous eras. Asimov writes,

“The young specialist in English Lit, having quoted me, went on to lecture me severely on the fact that in every century people have thought they understood the universe at last, and in every century they were proved to be wrong. It follows that the one thing we can say about our modern “knowledge” is that it is wrong. The young man then quoted with approval what Socrates had said on learning that the Delphic oracle had proclaimed him the wisest man in Greece. “If I am the wisest man,” said Socrates, “it is because I alone know that I know nothing.” the implication was that I was very foolish because I was under the impression I knew a great deal. My answer to him was, “John, when people thought the earth was flat, they were wrong. When people thought the earth was spherical, they were wrong. But if you think that thinking the earth is spherical is just as wrong as thinking the earth is flat, then your view is wronger than both of them put together.”

The mistake John makes is the same mistake many still make today when it comes to peacemaking. They think that “Both sides” must be equally right or equally wrong, and that the best position is to pretend we aren’t wise enough to know the difference. But as Asimov demonstrates, this is utter foolishness. Truth is not so elusive that we cannot stand on the facts in front of our faces. And, to be honest, those who often make this argument against biblical peacemaking cherry-pick the “truths” that they find obvious and the truths that inexplicably can’t be known by anyone. How convenient that we just can’t know if a policy is racist, but we can for sure know if a policy is economically sound?

Esau McCaulley is an African American Anglican priest and professor at Wheaton. He studied with N. T. Wright in Scotland for his doctorate. He writes about this in his new book Reading While Black:

“What, then, does peacemaking involve and what does it have to do with the church’s political witness? Biblical peacemaking… involves assessing the claims of groups in conflict and making a judgment about who is correct and who is incorrect. Peacemaking, then, cannot be separated from truth telling. The church’s witness does not involve simply denouncing the excesses of both sides and making moral equivalencies. It involves calling injustice by its name. If the church is going to be on the side of peace in the United States, then there has to be an honest accounting of what this country has done and continues to do to Black and Brown people. Moderation or the middle ground is not always the loci of righteousness. Housing discrimination has to be named. Unequal sentences and unfair policing has to be named. Sexism and the abuse and commodification of the Black female body has to end. Otherwise any peace is false and unbiblical. Beyond naming there has to be some vision for the righting of wrongs and the restoration of relationships. The call to be peacemakers is the call for the church to enter the messy world of politics and point toward a better way of being human.”

One of the reasons why we often make these mistakes about Peacemaking is because we have faulty mental models. Here’s one of them. We imagine that the divisions we need to overcome are horizontal on the same plain. Some are over on one side of the plain—let’s call it the Left side—while others are over on the Right side of the plain. In this mental model, the division that exists is on a horizontal spectrum. This imagines that if we can just “meet together in the middle” we’d have peace. But the fundamental problem with this mental model is that we aren’t all on the same plain, whether Left or Right.

This mental model presumes that everyone is on equal footing, having equal status relative to others. But that’s not the biblical model. In the biblical model of peace, some are unjustly disadvantaged and others are unjustly advantaged. They aren’t starting on the same plain; some hold a position in society above and over others. So the way to peace in the biblical model isn’t merely meeting in the middle, it’s the high and mighty being brought low and the downtrodden being uplifted. Shalom isn’t achieved until everyone is brought to the same level, regardless of where they fall on the “Left” or the “Right.”

It’s a little early for Advent readings, but Mary the mother of Jesus has something to say about how Jesus brings peace to the world:

And Mary said: “My soul glorifies the Lord and my spirit rejoices in God my Savior, for he has been mindful of the humble state of his servant. From now on all generations will call me blessed, for the Mighty One has done great things for me—holy is his name. His mercy extends to those who fear him, from generation to generation. He has performed mighty deeds with his arm; he has scattered those who are proud in their inmost thoughts. He has brought down rulers from their thrones but has lifted up the humble. He has filled the hungry with good things but has sent the rich away empty. He has helped his servant Israel, remembering to be merciful to Abraham and his descendants forever, just as he promised our ancestors.” (Luke 1.46-55)

The Shalom of God isn’t just people agreeing to disagree or maintaining a truce. No, the Shalom of God is when God’s dream for humanity is realized: All of humanity reigning together on God behalf as God’s representatives, stewarding the earth’s resources as the gifts they are, caring for all God’s creatures as precious, honoring one another as fellow divine image-bearers, and sharing resources with one another in a society that celebrates our God-giving diversity. Everyone belongs. Everyone has all they need. Everyone lives out of the fullness of God’s life in and through them.

Peacemaking confronts everything short of God’s dream and builds toward the day when God’s Shalom is fully established on earth as it is in heaven.

October 19, 2020

From Volk to Spoke: Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s Transformational Encounter with the Black Christ in Harlem