Steph Post's Blog, page 27

September 10, 2016

Strange Magic: An Interview with Matthew Fogarty, author of Maybe Mermaids and Robots are Lonely

Today, I'm super excited to bring you an interview with Matthew Fogarty, author of the brilliant short story collection (with novella), Maybe Mermaids and Robots are Lonely. This is one of the best collections I've ready all year and I've been anxiously awaiting its debut on September 16th, so that I can share it with the rest of the world. Enjoy!

Steph Post: Maybe Mermaids and Robots are Lonely is like a love letter to childhood. The stories are rife with totemic childhood hallmarks: robots, mermaids, pirates, monsters, videogame characters, cowboys, astronauts, the list goes on... Opening this collection is like opening a treasure chest containing everything we ever wanted to be when we grew up (before we became jaded and realized that no, we were probably not going to grow fins). What gave you the inspiration for tapping into and channeling the idealized (and also real) experiences of childhood?

Matthew Fogarty: Oh wow, thank you. Yeah, I'm not sure where to begin answering this question.

The collection really started as an experiment with freeing myself up to write anything and, more specifically, to write the kinds of stories I like to read. Entering the second year of my MFA, I was feeling aimless (in a bad way) with my fiction—I’d been trying to write the kinds of “serious” and intensely adult stories I thought I needed to write, but everything was coming out flat and emotionless and well-worn; I hated the characters I was writing. And so I experimented with removing any sense of responsibility or any “supposed to” and just freed myself up to write and explore and have fun. And, thinking only that I wanted to write something involving a robot and a love story, I wrote the title piece.

And maybe that’s the connection to childhood, this release from responsibility and this opening up of possibilities. I was obsessed with the idea of childlike wonder. I wanted the chance, in my writing, to let the world be wondrous and exciting and new again. After a while, I also became obsessed with the idea of nostalgia for a time or a place or a thing that never existed. I’d been revisiting the movies of John Hughes and thinking about how they seemed to so perfectly capture my childhood and young adulthood, but how the worlds they depict weren’t real or realistic even when the movies were first released.

Maybe it all has something to do with growing up in the suburbs of Detroit and the weirdness and strange magic of that space: that it’s neither city nor country, that it’s this bizarrely “un” place. Which, as a kid, felt blank or boring or generic, but now, looking back, feels unique and magical. That within our square-mile subdivision we had a park and a river (really, a creek) and a block of trees that felt at the time, and still does, like an endless, boundaryless forest in which all manner of things are possible.

SP: Because some of these stories are so delightfully wild, I'm interested in your story-creation process. Do you sit around and just ask yourself "what if" questions? As in, "well, what if a mermaid and robot fell in love?" or, "what if Bigfoot needed a temp job?" Do these ideas hit you like a bolt of lightening while driving down the road or are they highly developed?

MF: A little of all of those, I'd say. Many started with an inkling or an emotion or a word or a line or a sound and grew from there. The hardest work was letting myself follow them into the weird. At a certain point, I realized many of the stories I was writing involved characters that were almost legendary or mythological, but in some way distinctly American, characters that I'd grown up with and that helped form my understanding of the world. From there, I identified a bunch of other characters that felt like they deserved a story, characters I could throw into situations I wanted to explore or that I could pair with an emotion or an idea.

Some stories are premise-based what-ifs, but I find those stories to be toughest just because, at least until I dive deeply into them, I feel like I'm floundering and awkward and aimless, hoping to find my role in the telling of the story. For example, I knew I wanted to write something involving a zombie theme park. It took two years of actively and passively thinking about it, and living with it and letting it germinate, to develop it into an actual story idea. Even then, there were maybe a dozen or so false starts—me trying to write into the story or write through the story or write around the story, trying to approach it from various angles and pull on some of the strings I developed and all of it failing to gain any momentum. And then one day I found the voice, the tone of the narration, and I had it—three weeks later I had most of a first draft.

SP: The sections in the collection are broken down and titled with prepositions: Under, over, between, above, away. What was the reasoning for the section breakdowns and what is the meaning behind the titles?

MF: Let me say first, structuring a flash collection is maybe the hardest part of writing a flash collection. And in this case, many of these ideas are actually credited to the folks at Stillhouse and, in particular, my wonderful editor, Justin Lafreniere. Originally, I had thought of all of the stories as little rivers or creeks that all empty into the novella, which collects everything thematically and plotwise and plays with it all some more and twists things and so on. It's how Etgar Keret and Stuart Dybek structure many of their collections.

But Justin made some keen observations: for one, given the length of the collection and the sheer number of stories, it was hard to maintain any kind of readerly momentum or to make any real sense out of the collection as a whole without any signposts of some sort; for another, the stories play in so many different worlds, there needed to be something to help them cohere. He suggested grouping the stories into a few sections with the novella in the middle. Eventually, we struck on the idea of how these stories relate to each other in space. I came up with loose groupings of stories and Justin took the idea back to his editorial team. Together, we came up with the order.

Originally, I was firmly opposed to section titles. I like to let my work speak for itself and I didn't want to ruin the way the stories were naturally kind of working off each other. But Justin pushed me to make it work, and I settled on the prepositions. Maybe initially they were an attempt to be cute, but the more I lived with them and read and reread the collection throughout the editing process, the more I've come to love the way they both provide some coherence among the stories in the book while also challenging some of the stories and driving them perhaps deeper than I ever could have intended.

SP: Many of the stories have a fairy tale or allegorical type structure. I'm thinking especially in the novella "The Dead Dream of Being Undead," but also in shorter works such as the title story. Were you influced by allegories directly or is this a reflection of the overall theme of childhood, as most often it is children who are exposed to this style of storytelling?

MF: In one sense, I think it’s a storytelling strategy. There’s something so unequivocally firm about the allegorical or fable-like telling, something we so readily accept as truthful on some figurative level. And I love testing the limits of this, of exploring how readily we might accept something presented in that style or how long we might choose to stay with something that begins to deviate or expand or transmorph out of that old fablelike telling into something wholly, magically, wondrously different. I like Borges and Calvino a lot, and they were masters of this.

Another thought as I was working on the collection was that there were so many stories or ideas or characters floating around in my memory that seemed like they were real, like they already existed on paper or in a book, like they were firm and well-worn. I feel like I remember stories about mermaids and robots and astronauts flying to the moon in a barrel. But of course I don’t remember those stories, my memory is faulty, it’s swirled all these ideas, these little pieces of culture and history and geography and so on into some weird false fairyland. I don’t know if others have this same experience or if they experience these false memories of iconic or legendary characters the same way I do. But I want to tell those stories, to make them firm, to make them as real as the mythologies I remember.

SP: In many of my favorite stories, a single image or object is focused on as a way to convey "unspeakable" emotions. I'm thinking of the chair in "River to Shanghai" or the cooler in "Plain Burial." Bigfoot's overcoat. Was this a conscious decision- to use objects to express emotions?

MF: This is also a storytelling strategy, I guess. I'm not sure how consciously I deploy it. It's always kind of a happy accident, whether the story grew naturally out of a particular object or an object just happens to show up in a story. Once I get past that initial creative burst of WHOOSH that splatters the start of a story on the page and the actual real work begins, I begin to see objects as things I can work with and out of which I can tease more story and more ideas.

I don't say this in relation to my own work, but it's one of the things I love in fiction and in storytelling generally—the idea of using an object as both a focal point that concentrates the reader's or the audience's attention and as a tool of distraction or misdirection. Aaron Sorkin does it. David Mamet does it. Stuart Dybek does it. Etgar Keret has a number of stories that center the reader's attention on an object. Aimee Bender does it often. Caitlin McGuire does it. It's a cool dramatic and rhetorical trick that I try to get my students to do in essay writing, as well.

SP: I noticed that many of the stories highlight the landscape or natural elements. Water in particular, but also the earth itself, seems to play a keen role in explore the relationship between character. This is most evident in my favorite piece (and it took a while to decide how to use the word 'favorite' there)- "We Are Swimmers." Do you think that your emphasis on nature harkens again back to the themes of childhood and how children experience the world?

MF: Yeah, that's definitely true. I think, more than just childhood and children in general, it has to do with growing up in the suburbs and my childhood in particular. My understanding and experience of nature was formed in this weird in-between space, where elements of the city and the industrial blend with elements of the country and the natural. Something went awry in that blending, and we ended up with a space that was not quite city, not quite country, a space that was simply "un." And I should add that these aren't my ideas at all, that there are plenty others who've written about this, including Stewart O'Nan in Last Night at the Lobster, which is a fantastic book set in a Red Lobster that's about to close but is enduring a snowstorm.

And I guess, more literally, much of the landscape here is the landscape of my childhood in the suburbs of Detroit: the crumbling industrial center, the relatively affluent and green suburbs, the majesty of the great lakes. My grandmother lived in a cottage on a hill on the Canadian side of Lake Erie near Buffalo. That house, which was ramshackle and threatening to fall into the drink but nonetheless magical, and that beach, which often overtaken by rotting seaweed but nonetheless beautiful, are where my sisters and I had our most awesome adventures.

SP: To wrap up, I say that we end on love. Although there are heartbreaking moments in these stories, there is a pervading sense of buoyancy. A steadfast belief in hope that is refreshing, perhaps because it is so absent in much of modern literature. There is a purity in the way you convey love, no more so than in "Maybe Mermaids and Robots are Lonely." The whole time I was reading this story, I was waiting for the crushing ending, the expected 'we can't have what we want because we're all different and life sucks' ending, but instead, the story closes with the belief in the power of love. It's not cheesy. It's not sappy. It's honest and hopeful and shocking, because it dares to be so pure. Do you think these themes and types of stories are missing from the contemporary lit landscape? Do you think they are needed? And were you deliberately treading on this ground or is this more a reflection of the way you personally experience the world?

MF: I don't know. I'm not sure how to think of myself in relation to the contemporary lit landscape and I really don't feel like any kind of authority on what types of stories we do and don't need. Certainly, as far as the contemporary lit landscape goes, we don't necessarily need another straight white dude writer from the suburbs. There are plenty of us out there and all the stories of that generic experience have been pretty well told by writers who are better at writing than I am. But I do know that I love to write, that there are elements of how I've experienced the world that are both singular to me and also, on some level, touch on ideas or themes or emotions that we all experience in our own ways. There are stories out there that feel like they should exist but don't. And so I write and all I can write, all I can ever hope to write, are the stories only I can write, the stories that reflect my unique and subjective experience of the world.

It's inevitable in all this that I end up writing the types of stories that I like to read. So do I wish there were more stories like that? Of course. Absolutely. I wish there were more happy stories that explore the joy and whimsy in the world. I wish there were more stories that explore emotions other than devastation and longing. But not everyone is so fortunate as to spend their time doing that. There's ugly and there's hatred in the world. Certainly, there's truth and understanding and empathy to be found in stories that plumb those depths. There are plenty of voices writing into and around experiences of those depths—voices that are bolder and more important than mine.

I sometimes feel limited in my capacity to fight back the ugly and the hatred and the evil. It's a feeling that happens often when I sit down to write or, more often, when I decide there's no reason to sit down to write. And I don't know the answer and, again, this is just me and my thoughts. And I don't mean any of this as naively as it may sound. But I think there's some value in those times, that one other way to fight back the bad is to make something beautiful, to add to the beauty in the world. My work doesn't always live up to that lofty goal, but maybe there's something of merit in the trying.

"Maybe Mermaids" is one of those stories. I don't know if all of this was in my mind as I wrote it. Rather, it was me just letting myself write whatever I wanted, whatever felt real to me, whatever felt like mine. When I was a kid, my parents kept boxes full of books—children's books, mostly, and encyclopedias and school books—in our basement and during tornado warnings, we'd all go down to the basement and read. As an adult, I'm struck by how prominent and happy those afternoons are in my memory even though I know they can't have happened more than once every couple of years. But I wanted to write one of those stories, one of the stories I'd read in a children's book or an encyclopedia or a science book and what came out was a little bit of all of those things.

Thanks so much to Matt Fogarty for fielding my relentless questions and for bringing Maybe Mermaids and Robots are Lonely into the world. Be sure to pick up your copy on September 16th! It will be worth it; I promise.

Steph Post: Maybe Mermaids and Robots are Lonely is like a love letter to childhood. The stories are rife with totemic childhood hallmarks: robots, mermaids, pirates, monsters, videogame characters, cowboys, astronauts, the list goes on... Opening this collection is like opening a treasure chest containing everything we ever wanted to be when we grew up (before we became jaded and realized that no, we were probably not going to grow fins). What gave you the inspiration for tapping into and channeling the idealized (and also real) experiences of childhood?

Matthew Fogarty: Oh wow, thank you. Yeah, I'm not sure where to begin answering this question.

The collection really started as an experiment with freeing myself up to write anything and, more specifically, to write the kinds of stories I like to read. Entering the second year of my MFA, I was feeling aimless (in a bad way) with my fiction—I’d been trying to write the kinds of “serious” and intensely adult stories I thought I needed to write, but everything was coming out flat and emotionless and well-worn; I hated the characters I was writing. And so I experimented with removing any sense of responsibility or any “supposed to” and just freed myself up to write and explore and have fun. And, thinking only that I wanted to write something involving a robot and a love story, I wrote the title piece.

And maybe that’s the connection to childhood, this release from responsibility and this opening up of possibilities. I was obsessed with the idea of childlike wonder. I wanted the chance, in my writing, to let the world be wondrous and exciting and new again. After a while, I also became obsessed with the idea of nostalgia for a time or a place or a thing that never existed. I’d been revisiting the movies of John Hughes and thinking about how they seemed to so perfectly capture my childhood and young adulthood, but how the worlds they depict weren’t real or realistic even when the movies were first released.

Maybe it all has something to do with growing up in the suburbs of Detroit and the weirdness and strange magic of that space: that it’s neither city nor country, that it’s this bizarrely “un” place. Which, as a kid, felt blank or boring or generic, but now, looking back, feels unique and magical. That within our square-mile subdivision we had a park and a river (really, a creek) and a block of trees that felt at the time, and still does, like an endless, boundaryless forest in which all manner of things are possible.

SP: Because some of these stories are so delightfully wild, I'm interested in your story-creation process. Do you sit around and just ask yourself "what if" questions? As in, "well, what if a mermaid and robot fell in love?" or, "what if Bigfoot needed a temp job?" Do these ideas hit you like a bolt of lightening while driving down the road or are they highly developed?

MF: A little of all of those, I'd say. Many started with an inkling or an emotion or a word or a line or a sound and grew from there. The hardest work was letting myself follow them into the weird. At a certain point, I realized many of the stories I was writing involved characters that were almost legendary or mythological, but in some way distinctly American, characters that I'd grown up with and that helped form my understanding of the world. From there, I identified a bunch of other characters that felt like they deserved a story, characters I could throw into situations I wanted to explore or that I could pair with an emotion or an idea.

Some stories are premise-based what-ifs, but I find those stories to be toughest just because, at least until I dive deeply into them, I feel like I'm floundering and awkward and aimless, hoping to find my role in the telling of the story. For example, I knew I wanted to write something involving a zombie theme park. It took two years of actively and passively thinking about it, and living with it and letting it germinate, to develop it into an actual story idea. Even then, there were maybe a dozen or so false starts—me trying to write into the story or write through the story or write around the story, trying to approach it from various angles and pull on some of the strings I developed and all of it failing to gain any momentum. And then one day I found the voice, the tone of the narration, and I had it—three weeks later I had most of a first draft.

SP: The sections in the collection are broken down and titled with prepositions: Under, over, between, above, away. What was the reasoning for the section breakdowns and what is the meaning behind the titles?

MF: Let me say first, structuring a flash collection is maybe the hardest part of writing a flash collection. And in this case, many of these ideas are actually credited to the folks at Stillhouse and, in particular, my wonderful editor, Justin Lafreniere. Originally, I had thought of all of the stories as little rivers or creeks that all empty into the novella, which collects everything thematically and plotwise and plays with it all some more and twists things and so on. It's how Etgar Keret and Stuart Dybek structure many of their collections.

But Justin made some keen observations: for one, given the length of the collection and the sheer number of stories, it was hard to maintain any kind of readerly momentum or to make any real sense out of the collection as a whole without any signposts of some sort; for another, the stories play in so many different worlds, there needed to be something to help them cohere. He suggested grouping the stories into a few sections with the novella in the middle. Eventually, we struck on the idea of how these stories relate to each other in space. I came up with loose groupings of stories and Justin took the idea back to his editorial team. Together, we came up with the order.

Originally, I was firmly opposed to section titles. I like to let my work speak for itself and I didn't want to ruin the way the stories were naturally kind of working off each other. But Justin pushed me to make it work, and I settled on the prepositions. Maybe initially they were an attempt to be cute, but the more I lived with them and read and reread the collection throughout the editing process, the more I've come to love the way they both provide some coherence among the stories in the book while also challenging some of the stories and driving them perhaps deeper than I ever could have intended.

SP: Many of the stories have a fairy tale or allegorical type structure. I'm thinking especially in the novella "The Dead Dream of Being Undead," but also in shorter works such as the title story. Were you influced by allegories directly or is this a reflection of the overall theme of childhood, as most often it is children who are exposed to this style of storytelling?

MF: In one sense, I think it’s a storytelling strategy. There’s something so unequivocally firm about the allegorical or fable-like telling, something we so readily accept as truthful on some figurative level. And I love testing the limits of this, of exploring how readily we might accept something presented in that style or how long we might choose to stay with something that begins to deviate or expand or transmorph out of that old fablelike telling into something wholly, magically, wondrously different. I like Borges and Calvino a lot, and they were masters of this.

Another thought as I was working on the collection was that there were so many stories or ideas or characters floating around in my memory that seemed like they were real, like they already existed on paper or in a book, like they were firm and well-worn. I feel like I remember stories about mermaids and robots and astronauts flying to the moon in a barrel. But of course I don’t remember those stories, my memory is faulty, it’s swirled all these ideas, these little pieces of culture and history and geography and so on into some weird false fairyland. I don’t know if others have this same experience or if they experience these false memories of iconic or legendary characters the same way I do. But I want to tell those stories, to make them firm, to make them as real as the mythologies I remember.

SP: In many of my favorite stories, a single image or object is focused on as a way to convey "unspeakable" emotions. I'm thinking of the chair in "River to Shanghai" or the cooler in "Plain Burial." Bigfoot's overcoat. Was this a conscious decision- to use objects to express emotions?

MF: This is also a storytelling strategy, I guess. I'm not sure how consciously I deploy it. It's always kind of a happy accident, whether the story grew naturally out of a particular object or an object just happens to show up in a story. Once I get past that initial creative burst of WHOOSH that splatters the start of a story on the page and the actual real work begins, I begin to see objects as things I can work with and out of which I can tease more story and more ideas.

I don't say this in relation to my own work, but it's one of the things I love in fiction and in storytelling generally—the idea of using an object as both a focal point that concentrates the reader's or the audience's attention and as a tool of distraction or misdirection. Aaron Sorkin does it. David Mamet does it. Stuart Dybek does it. Etgar Keret has a number of stories that center the reader's attention on an object. Aimee Bender does it often. Caitlin McGuire does it. It's a cool dramatic and rhetorical trick that I try to get my students to do in essay writing, as well.

SP: I noticed that many of the stories highlight the landscape or natural elements. Water in particular, but also the earth itself, seems to play a keen role in explore the relationship between character. This is most evident in my favorite piece (and it took a while to decide how to use the word 'favorite' there)- "We Are Swimmers." Do you think that your emphasis on nature harkens again back to the themes of childhood and how children experience the world?

MF: Yeah, that's definitely true. I think, more than just childhood and children in general, it has to do with growing up in the suburbs and my childhood in particular. My understanding and experience of nature was formed in this weird in-between space, where elements of the city and the industrial blend with elements of the country and the natural. Something went awry in that blending, and we ended up with a space that was not quite city, not quite country, a space that was simply "un." And I should add that these aren't my ideas at all, that there are plenty others who've written about this, including Stewart O'Nan in Last Night at the Lobster, which is a fantastic book set in a Red Lobster that's about to close but is enduring a snowstorm.

And I guess, more literally, much of the landscape here is the landscape of my childhood in the suburbs of Detroit: the crumbling industrial center, the relatively affluent and green suburbs, the majesty of the great lakes. My grandmother lived in a cottage on a hill on the Canadian side of Lake Erie near Buffalo. That house, which was ramshackle and threatening to fall into the drink but nonetheless magical, and that beach, which often overtaken by rotting seaweed but nonetheless beautiful, are where my sisters and I had our most awesome adventures.

SP: To wrap up, I say that we end on love. Although there are heartbreaking moments in these stories, there is a pervading sense of buoyancy. A steadfast belief in hope that is refreshing, perhaps because it is so absent in much of modern literature. There is a purity in the way you convey love, no more so than in "Maybe Mermaids and Robots are Lonely." The whole time I was reading this story, I was waiting for the crushing ending, the expected 'we can't have what we want because we're all different and life sucks' ending, but instead, the story closes with the belief in the power of love. It's not cheesy. It's not sappy. It's honest and hopeful and shocking, because it dares to be so pure. Do you think these themes and types of stories are missing from the contemporary lit landscape? Do you think they are needed? And were you deliberately treading on this ground or is this more a reflection of the way you personally experience the world?

MF: I don't know. I'm not sure how to think of myself in relation to the contemporary lit landscape and I really don't feel like any kind of authority on what types of stories we do and don't need. Certainly, as far as the contemporary lit landscape goes, we don't necessarily need another straight white dude writer from the suburbs. There are plenty of us out there and all the stories of that generic experience have been pretty well told by writers who are better at writing than I am. But I do know that I love to write, that there are elements of how I've experienced the world that are both singular to me and also, on some level, touch on ideas or themes or emotions that we all experience in our own ways. There are stories out there that feel like they should exist but don't. And so I write and all I can write, all I can ever hope to write, are the stories only I can write, the stories that reflect my unique and subjective experience of the world.

It's inevitable in all this that I end up writing the types of stories that I like to read. So do I wish there were more stories like that? Of course. Absolutely. I wish there were more happy stories that explore the joy and whimsy in the world. I wish there were more stories that explore emotions other than devastation and longing. But not everyone is so fortunate as to spend their time doing that. There's ugly and there's hatred in the world. Certainly, there's truth and understanding and empathy to be found in stories that plumb those depths. There are plenty of voices writing into and around experiences of those depths—voices that are bolder and more important than mine.

I sometimes feel limited in my capacity to fight back the ugly and the hatred and the evil. It's a feeling that happens often when I sit down to write or, more often, when I decide there's no reason to sit down to write. And I don't know the answer and, again, this is just me and my thoughts. And I don't mean any of this as naively as it may sound. But I think there's some value in those times, that one other way to fight back the bad is to make something beautiful, to add to the beauty in the world. My work doesn't always live up to that lofty goal, but maybe there's something of merit in the trying.

"Maybe Mermaids" is one of those stories. I don't know if all of this was in my mind as I wrote it. Rather, it was me just letting myself write whatever I wanted, whatever felt real to me, whatever felt like mine. When I was a kid, my parents kept boxes full of books—children's books, mostly, and encyclopedias and school books—in our basement and during tornado warnings, we'd all go down to the basement and read. As an adult, I'm struck by how prominent and happy those afternoons are in my memory even though I know they can't have happened more than once every couple of years. But I wanted to write one of those stories, one of the stories I'd read in a children's book or an encyclopedia or a science book and what came out was a little bit of all of those things.

Thanks so much to Matt Fogarty for fielding my relentless questions and for bringing Maybe Mermaids and Robots are Lonely into the world. Be sure to pick up your copy on September 16th! It will be worth it; I promise.

Published on September 10, 2016 11:36

September 9, 2016

A Conversation with Nature... (and Marrow Island author Alexis M. Smith)

This week, I'm excited to bring you an interview with Alexis M. Smith, author of

Marrow Island

, a haunting tale of love, loss and discovery in the wilds of the Pacific Northwest. Read on!

Steph Post: Lucie’s story in Marrow Island is told back and forth across time with chapters alternating between 2016 and 2014. In this way, we slowly learn of the traumatic events that happened in the past, while the story simultaneously moves forward with the repercussions of those events. It’s an interesting structural technique and one that reminds me a little of Evie Wyld’s All the Birds, Singing . To create these dual narratives in time, did you write each separately and then weave them together or did you write straight through, flipping back and forth in your own mind as you wrote?

Alexis Smith: I loved All the Birds, Singing! I was struck by her use of time as structure as well (though I read it after I had finished Marrow Island).

When I began writing I thought that I would write the story linearly (beginning with her return to the islands, moving through her experiences there, then moving on to the woods and the aftermath). As it turns out, I get bored by linear narratives. I couldn’t sustain it. My mind was skipping ahead, then looking back, almost constantly. So I just started writing the chapters as you read them. There was more joy in writing back and forth like that, even if it did take more concentration not to reveal too much, too soon.

SP: While Marrow Island focuses heavily on Lucie’s introspection and her relationships with her boyfriend Carey and childhood friend Katie, there is a lot of natural science going on in both narratives. Marrow Island is home to an eco-colony whose members are focused on healing the island, mainly by means of reviving the soil with mushrooms. Are the scientific practices used by the colony members real? While researching, did you ever visit a place like the colony you describe?

AS: Yes! Mycoremediation is a real thing. My deployment of it in the novel is pure fantasy, though. As far as I know, no one has tried it on such a large scale.

I didn’t visit any eco-communes or intentional communities, or, indeed, any mushroom farms or mycoremediation sites. I read a lot, watched videos, interviewed people, and became an amateur mycologist. I spend a lot of time out in the woods, and just walking around the city observing urban flora and fauna, so I took lots of pictures on my phone of mushrooms I encountered in the world, then I came home to my field guides and mushroom forums online and identified what I had seen. It’s an obsession I haven’t given up. If you follow me on Instagram you’ll likely still see a mushroom every now and then.

SP: Marrow and Orwell Island are located in Washington and Malheur National Forest, where Lucie lives in 2016, is located in Oregon. In both places, Lucie falls for the lushness of the natural world around her. How important is the Pacific Northwest setting to the story itself?

AS: Stories very often arise from landscapes for me. Whether it’s the Pacific Northwest, where I was born and have lived most of my life, or New Mexico, where my mom has lived for the last fifteen years, the stories are there and I’m open to them. It’s a sort of conversation with the natural world that I’ve been having since I was a little kid, playing in the woods outside my grandparents’ homestead in Alaska.

SP: Without going into detail, I’ll just say that the novel ends with a terrifyingly gorgeous, image-heavy scene. Did you have this particular scene in mind when you started Marrow Island? It carries such a weight and I could see it guiding the narrative instead of being only a conclusion.

AS: I envisioned that scenario as the ending, yes—it was definitely a guide for me throughout the book—though I didn’t know exactly what Lucie would do in that scene, or what the final image and words would be. I like to keep an ending in mind as I write, so that I know where I’m going. To your previous question: this scene was inspired by a solo road trip through southern Oregon, during a thunder storm. I was maybe fifty pages into the novel at that point, and felt adrift. I was plugging along but without momentum. Driving alone through the Siskiyou National Forest on a stormy spring brought out that scene. This might be my only useful writing advice: when you’re not sure where your story’s going, get to the woods.

SP: In many ways, Marrow Island is a tale of loss. Lost love, lost trust, lost land. Especially in regards to the island itself, and the damage it sustained in an oil refinery explosion, the wounds you explore in the novel don’t seem to heal. Is there a message of hope here as well? Does there have to be?

AS: Oh, good question…

Hope is such a tricky concept for me. I go back and forth: sometimes I have hope that humans will get their shit together and stop killing each other and the planet; other days, the only hope I see is in the persistence of species other than our own, the ability of, say, mycelia to communicate with trees, or protect bees from colony colapse. Ultimately, I want there to be an end to the greed that is causing so much suffering, and I see so many examples of flawed but beautiful human beings doing their best to learn from time spent in contemplation of the natural world around us. Right now my heart is with the people of Standing Rock, facing down dogs and bulldozers and corporate power. They give me hope. The Marrow colonists are meant to give hope, too, I guess, however stacked the odds against them.

Thanks to Alexis M. Smith for stopping by! Be sure to check out Marrow Island , as well as Smith's first novel, Glaciers . Happy Reading!

Steph Post: Lucie’s story in Marrow Island is told back and forth across time with chapters alternating between 2016 and 2014. In this way, we slowly learn of the traumatic events that happened in the past, while the story simultaneously moves forward with the repercussions of those events. It’s an interesting structural technique and one that reminds me a little of Evie Wyld’s All the Birds, Singing . To create these dual narratives in time, did you write each separately and then weave them together or did you write straight through, flipping back and forth in your own mind as you wrote?

Alexis Smith: I loved All the Birds, Singing! I was struck by her use of time as structure as well (though I read it after I had finished Marrow Island).

When I began writing I thought that I would write the story linearly (beginning with her return to the islands, moving through her experiences there, then moving on to the woods and the aftermath). As it turns out, I get bored by linear narratives. I couldn’t sustain it. My mind was skipping ahead, then looking back, almost constantly. So I just started writing the chapters as you read them. There was more joy in writing back and forth like that, even if it did take more concentration not to reveal too much, too soon.

SP: While Marrow Island focuses heavily on Lucie’s introspection and her relationships with her boyfriend Carey and childhood friend Katie, there is a lot of natural science going on in both narratives. Marrow Island is home to an eco-colony whose members are focused on healing the island, mainly by means of reviving the soil with mushrooms. Are the scientific practices used by the colony members real? While researching, did you ever visit a place like the colony you describe?

AS: Yes! Mycoremediation is a real thing. My deployment of it in the novel is pure fantasy, though. As far as I know, no one has tried it on such a large scale.

I didn’t visit any eco-communes or intentional communities, or, indeed, any mushroom farms or mycoremediation sites. I read a lot, watched videos, interviewed people, and became an amateur mycologist. I spend a lot of time out in the woods, and just walking around the city observing urban flora and fauna, so I took lots of pictures on my phone of mushrooms I encountered in the world, then I came home to my field guides and mushroom forums online and identified what I had seen. It’s an obsession I haven’t given up. If you follow me on Instagram you’ll likely still see a mushroom every now and then.

SP: Marrow and Orwell Island are located in Washington and Malheur National Forest, where Lucie lives in 2016, is located in Oregon. In both places, Lucie falls for the lushness of the natural world around her. How important is the Pacific Northwest setting to the story itself?

AS: Stories very often arise from landscapes for me. Whether it’s the Pacific Northwest, where I was born and have lived most of my life, or New Mexico, where my mom has lived for the last fifteen years, the stories are there and I’m open to them. It’s a sort of conversation with the natural world that I’ve been having since I was a little kid, playing in the woods outside my grandparents’ homestead in Alaska.

SP: Without going into detail, I’ll just say that the novel ends with a terrifyingly gorgeous, image-heavy scene. Did you have this particular scene in mind when you started Marrow Island? It carries such a weight and I could see it guiding the narrative instead of being only a conclusion.

AS: I envisioned that scenario as the ending, yes—it was definitely a guide for me throughout the book—though I didn’t know exactly what Lucie would do in that scene, or what the final image and words would be. I like to keep an ending in mind as I write, so that I know where I’m going. To your previous question: this scene was inspired by a solo road trip through southern Oregon, during a thunder storm. I was maybe fifty pages into the novel at that point, and felt adrift. I was plugging along but without momentum. Driving alone through the Siskiyou National Forest on a stormy spring brought out that scene. This might be my only useful writing advice: when you’re not sure where your story’s going, get to the woods.

SP: In many ways, Marrow Island is a tale of loss. Lost love, lost trust, lost land. Especially in regards to the island itself, and the damage it sustained in an oil refinery explosion, the wounds you explore in the novel don’t seem to heal. Is there a message of hope here as well? Does there have to be?

AS: Oh, good question…

Hope is such a tricky concept for me. I go back and forth: sometimes I have hope that humans will get their shit together and stop killing each other and the planet; other days, the only hope I see is in the persistence of species other than our own, the ability of, say, mycelia to communicate with trees, or protect bees from colony colapse. Ultimately, I want there to be an end to the greed that is causing so much suffering, and I see so many examples of flawed but beautiful human beings doing their best to learn from time spent in contemplation of the natural world around us. Right now my heart is with the people of Standing Rock, facing down dogs and bulldozers and corporate power. They give me hope. The Marrow colonists are meant to give hope, too, I guess, however stacked the odds against them.

Thanks to Alexis M. Smith for stopping by! Be sure to check out Marrow Island , as well as Smith's first novel, Glaciers . Happy Reading!

Published on September 09, 2016 14:46

September 6, 2016

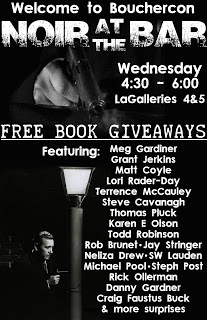

Bouchercon: Noir at the Bar

Heading to Bouchercon next week? Me too! This will be my first time attending the event and I'm excited to kick it off with a Noir at the Bar reading. And one with such a crazy, stellar line-up. Be sure to stop by!

Published on September 06, 2016 15:49

September 5, 2016

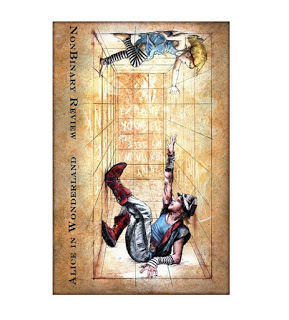

Alice-Ecila

In case you didn't know, I love all and anything related to Alice in Wonderland....

So, of course, I love Nonbinary Review's Alice Anthology, which was just released from Zoetic Press. And I'm thrilled and honored to have a poem- "Alice-Ecila" included in the edition. Cheers!

Published on September 05, 2016 15:41

August 25, 2016

Interview in Fiction Southeast

So today I'm hanging out over at Fiction Southeast, talking about (basically) how hard writing is and how much it's worth it. Cheers!

Published on August 25, 2016 13:19

August 24, 2016

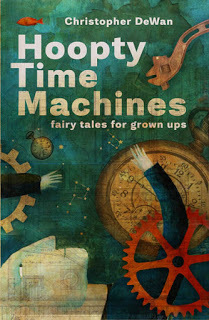

Of Wonder and Shadows: An Interview with Christopher DeWan, author of Hoopty Time Machines

Christopher DeWan's

Hoopty Time Machines: fairy tales for grown ups

debuts on September 22 and let me just say, you're in for a doozy. Wild, imaginative, poetic, and disturbingly familiar, the stories found in this collection are so much more than fairy tale reduxes. They are gem-like bits mined from our collective childhood imaginations, viewed through the lens of maturity and polished to a high shine. And a lot of them were written on the subway.... Christopher DeWan clearly has a fantastical mind and his interview doesn't fall short of the honesty and quirkiness that I so loved about his collection. Be sure to add Hoopty Time Machines to your To-Be-Read list, but in the mean time, sit back, relax and step into another world:

Steph Post: Hoopty Time Machines is a collection of flash fiction and what may be described as “mirco-fiction.” Several stories are only a single sentence long. What’s the secret to telling an entire story in such a condensed, limited space?

Christopher DeWan: A lot of the stories in Hoopty Time Machines got their start while I was living in New York City: I would use my morning subway commute to write, so if I stumbled on an interesting idea around City Hall, I knew I had to find a way to wrap up before my stop at Union Square. I think that really did help me hone in on an aesthetic of suddenness: how much can I squeeze in, how many worlds or ideas can I explode, in the next ten minutes?

A few years ago, I moved to Los Angeles to work as a screenwriter, and the writing I do for that is longer: nobody wants to buy a TV series that lasts for ten minutes. But screenwriting requires so much efficiency that I think my background writing flash has really helped: scenes have to start at the very last possible moment, and they have to end as quickly and effectively as possible. Screenwriting has also made my fiction tighter: there’s a story in Hoopty Time Machines that was initially around 2,000 words, and by the time I finished editing, it was 83 words long.

SP: As the complete title of the collection suggests, Hoopty Time Machines is comprised of “fairy tales for grown-ups.” Almost every story is in some way a modern re-imagining of a classic story. This includes everything from Hans Christian Andersen fairy tales to Greek myths to 20th century superhero adventures. What drew you to traditional children’s literature and why do you think adults still find these genres and stories so fascinating?

CD: You know when people say, “Write the book you want to read"? I think about the stories I used to read when I was a kid, and the way they plunged into my heart—and I really wanted the stories in this book to do that, somehow, to tap into some of that under-the-skin feeling of wow and wonder. So many books I read now, they’re so good, but I feel myself read them with my head instead of with my body. I wanted to see if I could reconnect with this other way that I used to read—with my body. My gateway into that wound up being these stories I read when I was younger—not just fairy tales and myths, but superheroes and backwoods monsters and Stephen King, too. I wanted to get back in touch with anything that gave me a vocabulary for that feeling of “Wow.”

SP: As I previously mentioned, all of the stories collected in Hoopty Time Machine are re-imagined fairy tales. Did you write these stories with the intention of putting them together in book form? Or were you just on a thematic kick for a while there and the collection grew from stories you were already writing?

CD: I don’t know how conscious this was at the beginning, but in retrospect, I think what was happening was that I hit an age where things stopped going the way I wanted. My relationships weren’t working out. I didn’t get the jobs I thought I would get. Things weren’t getting easier; they were getting harder. So my experience of the world was going through a transition from a very youthful, “fairy tale” way of thinking—the belief that I was always going to get what I wanted—into a harder, more realistic understanding: that often I would not get what I wanted, even when I worked hard, even when I thought I deserved it.

So, intentional or not, this was a theme that was on my mind: what happens to a fairy tale hero when they realize they aren’t going to get to be a hero, or at least not in the way they initially imagined. I think the stories in this book are, purposefully or not, about me learning to make that transition—learning that “Happily ever after” isn’t a place you earn and then arrive at, once and for all. It’s a place you make for yourself a little bit every day for the rest of your life.

SP: Although the stories in this collection are based on stories familiar to children, your versions are often gritty, violent and not exactly G-rated. Was this part of the subversion of the original fairy tales or are you expounding upon and modernizing the violence already found in the stories?

CD: We really maybe should have boldfaced the “for grown ups” part of the subtitle…

It was never my intention to “retell” classic fairy tales; I don’t think I ever once sat down to write what I thought was a clever new interpretation of an old story. For me, it always starts with a feeling, and what I found, as I started writing about these feelings, is that often these mythical characters were great vessels to convey the thing I was trying to articulate.

I think these fairy tales and myths and childhood heroes are lodged so deep in our collective brains, but also in its murkiest unlit corners. There is so much violence, so much that’s unexplained or impossible to understand or resolve—and I think that’s why they still feel so vital to me, and maybe it’s why I find them so helpful for exploring a lot of these murky feelings: there’s so much shadow.

SP: At the end of Hoopty Time Machines, you include a section titled “Notes and Origin Myths” in which you comment on every story in the collection. I’ve never seen this kind of personal annotation included in a book of short stories. What was the reason for this section? Did you write the commentary after you completed each story or did you go back and write each piece for the purpose of the published collection?

CD: Haha—the honest answer is that my publisher was worried our book was too short. But there were already so many stories in the collection, I didn’t want to overwhelm a reader by adding more—so I thought it might be fun to offer this sort of “DVD special feature,” a little extra “behind the scenes” for people who want it.

SP: Finally, to share the love- what books are you most looking forward to reading in the coming year?

CD: Ah, I’m falling so behind on my reading list! There are so many books I’m looking forward to reading, but the next bunch on my queue are Amber Sparks' The Unfinished World , Kelly Link’s Get in Trouble , and Samantha Hunt’s Mr. Splitfoot . I want to go to a cabin in the woods without internet and read all three of them in one big gulp, and probably fuel my dreams and nightmares for the next five years. Can’t wait.

Many thanks to Christopher DeWan for stopping by! Be sure to pick up your own Hoopty from Atticus Books on September 22. Cheers!

Steph Post: Hoopty Time Machines is a collection of flash fiction and what may be described as “mirco-fiction.” Several stories are only a single sentence long. What’s the secret to telling an entire story in such a condensed, limited space?

Christopher DeWan: A lot of the stories in Hoopty Time Machines got their start while I was living in New York City: I would use my morning subway commute to write, so if I stumbled on an interesting idea around City Hall, I knew I had to find a way to wrap up before my stop at Union Square. I think that really did help me hone in on an aesthetic of suddenness: how much can I squeeze in, how many worlds or ideas can I explode, in the next ten minutes?

A few years ago, I moved to Los Angeles to work as a screenwriter, and the writing I do for that is longer: nobody wants to buy a TV series that lasts for ten minutes. But screenwriting requires so much efficiency that I think my background writing flash has really helped: scenes have to start at the very last possible moment, and they have to end as quickly and effectively as possible. Screenwriting has also made my fiction tighter: there’s a story in Hoopty Time Machines that was initially around 2,000 words, and by the time I finished editing, it was 83 words long.

SP: As the complete title of the collection suggests, Hoopty Time Machines is comprised of “fairy tales for grown-ups.” Almost every story is in some way a modern re-imagining of a classic story. This includes everything from Hans Christian Andersen fairy tales to Greek myths to 20th century superhero adventures. What drew you to traditional children’s literature and why do you think adults still find these genres and stories so fascinating?

CD: You know when people say, “Write the book you want to read"? I think about the stories I used to read when I was a kid, and the way they plunged into my heart—and I really wanted the stories in this book to do that, somehow, to tap into some of that under-the-skin feeling of wow and wonder. So many books I read now, they’re so good, but I feel myself read them with my head instead of with my body. I wanted to see if I could reconnect with this other way that I used to read—with my body. My gateway into that wound up being these stories I read when I was younger—not just fairy tales and myths, but superheroes and backwoods monsters and Stephen King, too. I wanted to get back in touch with anything that gave me a vocabulary for that feeling of “Wow.”

SP: As I previously mentioned, all of the stories collected in Hoopty Time Machine are re-imagined fairy tales. Did you write these stories with the intention of putting them together in book form? Or were you just on a thematic kick for a while there and the collection grew from stories you were already writing?

CD: I don’t know how conscious this was at the beginning, but in retrospect, I think what was happening was that I hit an age where things stopped going the way I wanted. My relationships weren’t working out. I didn’t get the jobs I thought I would get. Things weren’t getting easier; they were getting harder. So my experience of the world was going through a transition from a very youthful, “fairy tale” way of thinking—the belief that I was always going to get what I wanted—into a harder, more realistic understanding: that often I would not get what I wanted, even when I worked hard, even when I thought I deserved it.

So, intentional or not, this was a theme that was on my mind: what happens to a fairy tale hero when they realize they aren’t going to get to be a hero, or at least not in the way they initially imagined. I think the stories in this book are, purposefully or not, about me learning to make that transition—learning that “Happily ever after” isn’t a place you earn and then arrive at, once and for all. It’s a place you make for yourself a little bit every day for the rest of your life.

SP: Although the stories in this collection are based on stories familiar to children, your versions are often gritty, violent and not exactly G-rated. Was this part of the subversion of the original fairy tales or are you expounding upon and modernizing the violence already found in the stories?

CD: We really maybe should have boldfaced the “for grown ups” part of the subtitle…

It was never my intention to “retell” classic fairy tales; I don’t think I ever once sat down to write what I thought was a clever new interpretation of an old story. For me, it always starts with a feeling, and what I found, as I started writing about these feelings, is that often these mythical characters were great vessels to convey the thing I was trying to articulate.

I think these fairy tales and myths and childhood heroes are lodged so deep in our collective brains, but also in its murkiest unlit corners. There is so much violence, so much that’s unexplained or impossible to understand or resolve—and I think that’s why they still feel so vital to me, and maybe it’s why I find them so helpful for exploring a lot of these murky feelings: there’s so much shadow.

SP: At the end of Hoopty Time Machines, you include a section titled “Notes and Origin Myths” in which you comment on every story in the collection. I’ve never seen this kind of personal annotation included in a book of short stories. What was the reason for this section? Did you write the commentary after you completed each story or did you go back and write each piece for the purpose of the published collection?

CD: Haha—the honest answer is that my publisher was worried our book was too short. But there were already so many stories in the collection, I didn’t want to overwhelm a reader by adding more—so I thought it might be fun to offer this sort of “DVD special feature,” a little extra “behind the scenes” for people who want it.

SP: Finally, to share the love- what books are you most looking forward to reading in the coming year?

CD: Ah, I’m falling so behind on my reading list! There are so many books I’m looking forward to reading, but the next bunch on my queue are Amber Sparks' The Unfinished World , Kelly Link’s Get in Trouble , and Samantha Hunt’s Mr. Splitfoot . I want to go to a cabin in the woods without internet and read all three of them in one big gulp, and probably fuel my dreams and nightmares for the next five years. Can’t wait.

Many thanks to Christopher DeWan for stopping by! Be sure to pick up your own Hoopty from Atticus Books on September 22. Cheers!

Published on August 24, 2016 03:00

August 23, 2016

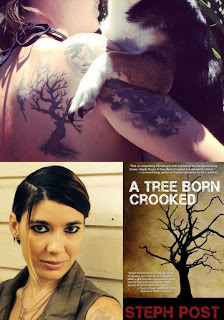

10 Authors with Tattoos Inspired by Their Own Books

So, as I've been pretty much hunkered down in my hobbit hole writing all summer, I've missed posting a few things. Here's an awesome one... Rob Hart, over at Electric Lit, put together a fantastic piece on authors who have gotten tattoos inspired by novels they've written. I might be one of them...

Published on August 23, 2016 14:47

August 12, 2016

A Love Letter to Lily: Steven Rowley and Lily and the Octopus

Anyone who knows anything about me knows that I am a dog person. I'm also, actually, a huge fan of cephalopods. So when I first saw the cover for Steven Rowley's recently released

Lily and the Octopus

, I thought, "Oh, perfect! A weenie dog and an octopus- my two favorite animals..." Then I read the inside cover: Old. Dog. Tumor. Gulp. The book sat on my dining room table and we eyeballed each other for a few days until finally I had the guts to open it to the first page. I steeled myself and started reading. And laughing. And eventually, yes, crying, and, in the end, recommending the book to anyone and everyone who would listen. Lily and the Octopus is the sort of novel that comes along every once in a while and wraps its arms around you, refusing to let go. And I wouldn't want it to.

I am thrilled and honored, then, to bring you an interview with Steven Rowley. If you're interested, but still nervous about checking out a "sad dog book," I think this conversation will alleviate some of your fears. For Lily and the Octopus so magnificently transcends that depressing label: in reality, it is a story not about death, but about life. About life and courage and the honest, raw vulnerability of unconditional love.

Steph Post:I’m not going to lie, I started reading Lily and the Octopus with some trepidation. Even before I cracked the spine I was nervous, because, well, it was obviously a book about a dog. And we all know how dog books end…. The last time I read a novel about a dog, I think it was Marley and Me, which has nothing on Lily and the Octopus by the way, I was a hot mess on the final page. I called my then-boyfriend in tears and was so upset that he thought something had happened to my real dogs who were, of course, snoozing through it all. So I knew that I was going to cry over Lily. And I did. Starting around page 250. My now-husband came home to find me curled up in a chair, with red eyes and eyeliner streaks, and all he could say was “you read that dog book after all, didn’t you?” What I’m getting at here, is that Lily and the Octopus is a book that makes a person cry. In a profound, beautiful, cathartic, but still sniffley and salty, kind of way. How much did you consider your readers’ emotional reactions when you were in the process of writing the novel? Did you ever want to not write Lily and the Octopus because of how you knew it would affect people?

Steven Rowley: This may sound terribly selfish, but I didn’t really consider the reader when I first sat down to write. Mostly, in retrospect, that’s because I didn’t set out to write a book. While Lily and the Octopus is very much a novel, I did have a dog named Lily who passed away from cancer in 2013. When she died, I was surprised by how sidelined I felt with grief. So when I decided to write about her, and about what that relationship meant to me, I was only doing so to help myself understand our bond and (hopefully) to heal. But it is the number one question I get: “Am I going to cry?” (Actually, the number one question is “Why an octopus?” But the trepidation is right up there!) And I can’t answer that for everyone. But I’m surprised by how much the idea of crying is a red flag for certain readers. I understand that for most of us our time to read is limited and there are many books vying for our eyes; life is hard and reading is an escape. But when I have such a connection with a book that it provokes a visceral reaction, I think that’s a good thing! When I finished the manuscript, I was very proud of it as a piece of writing, but even I didn’t know that it had the power to really connect with readers the way that it has. It’s been deeply humbling. And my goal was never to leave anyone despondent. If I walk you to that edge, I promise to help guide you back!

SP: I had to open up with the tear-jerking question, but there is so much more to Lily and the Octopus than sadness. Part of the reason readers are so enamored of the character of Lily is how you clearly and simply voiced her, a dachshund, through the mind of her human, the novel’s narrator Ted. We are able to hear Lily speak because Ted articulates her thoughts for her. This includes everything from her Cate Blanchett impressions, to her barking, exclamatory reaction to dolphins. As a dog person, reading Lily as talking seemed pretty normal, as I’m the sort of person, like Ted, who carries on one-sided conversations with her dogs and assumes that my dogs are doing the same back. Still, I’ve never seen this narrative technique used in fiction. Did voicing Lily just come naturally as you developed the story, or did you have to struggle to create a way for readers to both understand, and, more importantly, bond with the character of a dog?

SR: Thank you! I actually think the book has many laughs and encompasses the full spectrum of emotions. Lily speaks in two ways throughout the book. AT! TIMES! IN! ALL! CAPITAL! LETTERS! That is meant to be a literal translation of her barking. At other times she speaks conversationally, which is the main character Ted carrying on both sides of their dialogue. I heard someone describe this as a book about a talking dog and I had to correct them. Lily doesn’t actually speak (although she says volumes with a well-raised eyebrow). Novel writing is a very solitary occupation and when you’re alone a lot with the dog, it’s only a matter of time before you talk out loud to the dog. And then it’s not so long after that when the dog starts “talking” back. Finding that voice on the page came very naturally to me, and once I had settled on two ways to represent her speaking voice I was off to the races.

SP: In addition to communicating with Lily, Ted also has conversations, and encounters, with her tumor, which he sees and experiences as an octopus. It all makes perfect sense in the context of the novel and giving the octopus a voice is one of the elements that I think really works to enamor readers to Lily. Like Ted, readers are exasperated and furious at the octopus, especially as he is, obviously, a total asshole. This takes something scary, but impersonal, (a tumor) and turns it into something which can attempt to be reasoned with (a talking cephalopod), making it more personal, but even more infuriating. Giving the octopus a voice raised the bar for me, because it added such an extra, maddening layer to Lily’s story. How did you come up with the idea for the character of the octopus? Would you have been able to tell the same sort of story if Lily was described as simply having a tumor or dying of some other sort of disease?

SR: I don’t remember the single moment that I settled on an octopus, other than it came from thinking about the story in thematic terms. I wanted to write about attachment and how difficult in can be to let go. There was something about an octopus, something with tentacles and suction cups, that lent itself so perfectly to that goal. Also, many times cancer grows in tentacle-like ways through the body, reaching and unfurling and spreading. So an octopus made sense to me pretty much from the get go. It was never Lily and the Giraffe, or Lily and the Hippopotamus. I did not know that the octopus would speak. My goal from the outset was to write the emotional truth of the story, no matter how weird or rubbery the plot began to be. I think I even surprised myself when the octopus first spoke. 'Oh! That’s… interesting.’ But octopuses are so smart and scientists say they can learn and even play, so his speaking was just one more way to needle Ted and get under his skin. I do harbor some guilt for villainizing the octopus – they really are incredible creatures!

SP: Ted, whom Lily sometimes thinks of as Dad, is going through some of his own issues separate from Lily’s battle with the octopus. He is in therapy, very lonely and is stuck in the dating doldrums. Having him speak to a therapist could mislead the reader to think that perhaps Ted is crazy, or at the very least unstable, which would explain why his dog, and her tumor, can talk to him. The section “The Pelagic Zone” can easily be read as a complete delusion. But I think that reading Lily and the Octopus from that perspective negates the entire story. Were you ever concerned that readers might dismiss Ted, Lily and the octopus’s complex relationships as simply figments of his imagination?

SR: To me, more than it is the story about a man and his dog, Lily and the Octopus is about a man who is stuck in his life and how often the biggest obstacles blocking our paths are, if not outright imagined, greatly exaggerated. I would hope people wouldn’t think Ted is crazy. While the octopus is there from pretty much page one, I tried to introduce the other elements of magical realism carefully and integrate them naturally so as not to confuse the reader. As a writer, I am very fascinated with the human brain’s ability to create these elaborate constructs to keep us from having to face what we’re not yet capable of seeing. I think that’s what Ted is doing. Deep down he knows the deal, but the octopus and the epic battle in the Pelagic Zone are his way of processing loss. I did a lot of reading on Freud’s theories on loss, and many of us know the Kübler-Ross model outlining the five stages of grief. I worked hard to concoct Ted’s personal coping recipe from how the healthy brain is known to grieve.

SP: Despite the heart-stabbing, Lily and the Octopus is also riddled with humorous moments, even if they are dark, dark moments. How important was it to balance out the gravity of the story with Lily’s silly innocence or the absurdity of talking inflatable sharks?

SR: Being able to laugh, even through the darkest moments in life, is essential to sanity and survival. Especially being able to laugh at oneself and to remember to look at the world every now and again with childlike wonder. I find so much of life to be absurd when you think about it in the context of a bigger picture, or get too stuck in the trance of small self. So I wanted the book to be funny, because I wanted the book to be like life. There’s an honesty in humor. And dogs are really funny. They just are. You can’t write about dogs and not introduce a few laughs.

SP: The first chapter of Lily and the Octopus is pretty near perfect, but the author in me couldn’t help but imagine what your agent and editor first thought of it: A guy and his dog are discussing boys on a Thursday and then he discovers an octopus on his dog’s head. Did any of your first readers have a dubious reaction to the first few pages? Were there any odd or awkward discussions about the beginning of your novel?

SR: I’m very fond of the first chapter still, and it’s usually what I read at appearances and signings. Even through the long process of publishing a book, through endless rewrites, tweaks and edits, the first chapter is pretty much exactly what came pouring out the first time I sat down to write. In fact, before I understood that this was going to be a novel, there was a time I thought the first chapter was a short story. That it would somehow exist on its own. But I can see now how very frustrating it would be as a short story, because there isn’t really an ending or any kind of resolution. In terms of landing with an agent or a publisher, the whole book was a tough sell and the opening pages were indeed discussed. (Try reaching out to literary agencies and asking if they want to read a manuscript about a dog with an octopus stuck to her head. You can actually hear crickets in response.) What I learned was not that I needed to change the pages or alter my vision, but I had to become much smarter about how I talked about the book and how I pitched the manuscript to those I wanted and needed to read it. That meant talking about it in terms of an emotional arc, thematically as opposed to the actual plot. But the first pages are very much the book; they establish the relationship, the humor, the voice and I fought hard to keep them.

SP: Finally, I have to ask, how much of Lily and the Octopus is true? Lily was obviously your real dog and even now, looking back at your dedication to her in the acknowledgments section, I feel that choking around my heart that accompanied me throughout much of your novel. I’m assuming that the Trent and Byron mentioned are also the same as the two characters in the novel. Despite some of the departures from strict reality in the story, could Lily and the Octopus be considered a memoir? Or is more along the lines of an ode or a love letter, rendered in novel form?

SR: There’s no denying that there are elements of the book that are autobiographical, and that the work is deeply personal – but I don’t consider it a memoir. To me, as you say, it’s a love letter to Lily and to the spirit of our relationship. I do have a best friend named Trent and my boyfriend’s name is Byron; I borrowed those names as shorthand when I was developing those characters and they kind of stuck. And there are some similarities there. But in order to spotlight the relationship between Ted and Lily, I tried to remove Ted from humanity as much as possible. Ted has one friend, and one sibling, and one parent, whereas I am blessed with many friends and a large family. The Lily that’s in the novel, however, is exactly the dog that I had. And now I’m grateful to have this beautiful catalog of memories printed and sandwiched between two hard covers that stands alongside my most prized possessions – my collection of books.

Much love and many thanks to Steven Rowley for stopping by! And please be sure to check out Lily and the Octopus. It will be worth all the tears; I promise.

I am thrilled and honored, then, to bring you an interview with Steven Rowley. If you're interested, but still nervous about checking out a "sad dog book," I think this conversation will alleviate some of your fears. For Lily and the Octopus so magnificently transcends that depressing label: in reality, it is a story not about death, but about life. About life and courage and the honest, raw vulnerability of unconditional love.

Steph Post:I’m not going to lie, I started reading Lily and the Octopus with some trepidation. Even before I cracked the spine I was nervous, because, well, it was obviously a book about a dog. And we all know how dog books end…. The last time I read a novel about a dog, I think it was Marley and Me, which has nothing on Lily and the Octopus by the way, I was a hot mess on the final page. I called my then-boyfriend in tears and was so upset that he thought something had happened to my real dogs who were, of course, snoozing through it all. So I knew that I was going to cry over Lily. And I did. Starting around page 250. My now-husband came home to find me curled up in a chair, with red eyes and eyeliner streaks, and all he could say was “you read that dog book after all, didn’t you?” What I’m getting at here, is that Lily and the Octopus is a book that makes a person cry. In a profound, beautiful, cathartic, but still sniffley and salty, kind of way. How much did you consider your readers’ emotional reactions when you were in the process of writing the novel? Did you ever want to not write Lily and the Octopus because of how you knew it would affect people?

Steven Rowley: This may sound terribly selfish, but I didn’t really consider the reader when I first sat down to write. Mostly, in retrospect, that’s because I didn’t set out to write a book. While Lily and the Octopus is very much a novel, I did have a dog named Lily who passed away from cancer in 2013. When she died, I was surprised by how sidelined I felt with grief. So when I decided to write about her, and about what that relationship meant to me, I was only doing so to help myself understand our bond and (hopefully) to heal. But it is the number one question I get: “Am I going to cry?” (Actually, the number one question is “Why an octopus?” But the trepidation is right up there!) And I can’t answer that for everyone. But I’m surprised by how much the idea of crying is a red flag for certain readers. I understand that for most of us our time to read is limited and there are many books vying for our eyes; life is hard and reading is an escape. But when I have such a connection with a book that it provokes a visceral reaction, I think that’s a good thing! When I finished the manuscript, I was very proud of it as a piece of writing, but even I didn’t know that it had the power to really connect with readers the way that it has. It’s been deeply humbling. And my goal was never to leave anyone despondent. If I walk you to that edge, I promise to help guide you back!

SP: I had to open up with the tear-jerking question, but there is so much more to Lily and the Octopus than sadness. Part of the reason readers are so enamored of the character of Lily is how you clearly and simply voiced her, a dachshund, through the mind of her human, the novel’s narrator Ted. We are able to hear Lily speak because Ted articulates her thoughts for her. This includes everything from her Cate Blanchett impressions, to her barking, exclamatory reaction to dolphins. As a dog person, reading Lily as talking seemed pretty normal, as I’m the sort of person, like Ted, who carries on one-sided conversations with her dogs and assumes that my dogs are doing the same back. Still, I’ve never seen this narrative technique used in fiction. Did voicing Lily just come naturally as you developed the story, or did you have to struggle to create a way for readers to both understand, and, more importantly, bond with the character of a dog?

SR: Thank you! I actually think the book has many laughs and encompasses the full spectrum of emotions. Lily speaks in two ways throughout the book. AT! TIMES! IN! ALL! CAPITAL! LETTERS! That is meant to be a literal translation of her barking. At other times she speaks conversationally, which is the main character Ted carrying on both sides of their dialogue. I heard someone describe this as a book about a talking dog and I had to correct them. Lily doesn’t actually speak (although she says volumes with a well-raised eyebrow). Novel writing is a very solitary occupation and when you’re alone a lot with the dog, it’s only a matter of time before you talk out loud to the dog. And then it’s not so long after that when the dog starts “talking” back. Finding that voice on the page came very naturally to me, and once I had settled on two ways to represent her speaking voice I was off to the races.

SP: In addition to communicating with Lily, Ted also has conversations, and encounters, with her tumor, which he sees and experiences as an octopus. It all makes perfect sense in the context of the novel and giving the octopus a voice is one of the elements that I think really works to enamor readers to Lily. Like Ted, readers are exasperated and furious at the octopus, especially as he is, obviously, a total asshole. This takes something scary, but impersonal, (a tumor) and turns it into something which can attempt to be reasoned with (a talking cephalopod), making it more personal, but even more infuriating. Giving the octopus a voice raised the bar for me, because it added such an extra, maddening layer to Lily’s story. How did you come up with the idea for the character of the octopus? Would you have been able to tell the same sort of story if Lily was described as simply having a tumor or dying of some other sort of disease?

SR: I don’t remember the single moment that I settled on an octopus, other than it came from thinking about the story in thematic terms. I wanted to write about attachment and how difficult in can be to let go. There was something about an octopus, something with tentacles and suction cups, that lent itself so perfectly to that goal. Also, many times cancer grows in tentacle-like ways through the body, reaching and unfurling and spreading. So an octopus made sense to me pretty much from the get go. It was never Lily and the Giraffe, or Lily and the Hippopotamus. I did not know that the octopus would speak. My goal from the outset was to write the emotional truth of the story, no matter how weird or rubbery the plot began to be. I think I even surprised myself when the octopus first spoke. 'Oh! That’s… interesting.’ But octopuses are so smart and scientists say they can learn and even play, so his speaking was just one more way to needle Ted and get under his skin. I do harbor some guilt for villainizing the octopus – they really are incredible creatures!