Steph Post's Blog, page 29

March 29, 2016

Rock Bottom Noir: A Conversation with City of Rose author Rob Hart

Rob Hart is on fire. His first novel, New Yorked, debuted last year and since then he's been on a roll. His second novel with protagonist Ash McKenna, City of Rose, just hit shelves this past February and the third installment, South Village, will be available this coming October. He's also got this little writing thing going on with James Patterson... in addition to all the other projects either currently taking place or forming in his mind. Last year I was lucky enough to catch up with Rob to talk about New Yorked and now I'm thrilled to bring you a following up focusing on City of Rose and the continued adventures of Ash McKenna. Read on as Rob and I talk character development, strip clubs and why reading outside of your writing genre is important (among many other things). Enjoy!

Steph Post: City of Rose is the sequel to your debut with PI Ash McKenna, New Yorked. In New Yorked, the city itself was an essential character to the story and it seemed hard to imagine Ash functioning in any place else. Part of the evolution of Ash's story, though, is his move in City of Rose to Portland, Oregon. In writing this new novel, were you nervous about taking Ash out of his element? Were you concerned at all that since the city of New York is such a part of your identity of a writer, this drastic change of setting would be a jolt for readers?

Rob Hart: I was excited to take Ash out of New York. He's got this quality that's common to New York natives: That New York, and being raised there, has made them smarter and better than everyone else. It was time to dissuade him of that notion. And I needed the challenge--I wanted to get out of my own element. So in a lot of ways, me and Ash were on the same page--we were both navigating a place we weren't very familiar with. My hope is that it's exciting for the reader, too.

SP: In addition to shipping Ash all the way to the west coast, you land him in a vegan strip club. In all honesty, I found this a little startling at first. Maybe I'm old fashioned, but I'd never even heard of a vegan strip club.... Where on earth did you get the idea for this and why did you choose this as this the place where Ash ends up?

RH: Vegan strip clubs are real! Portland has at least one, maybe more. There's a law in Portland--any place that serves booze has to serve food. And they take food pretty seriously out there. I originally had him working in a coffee shop and it was okay, but not really clicking. Strip clubs in Portland are weird--the audience is usually equally male and female, at least in a lot of the ones I've been to. Going to a strip club in Portland is like going to a bowling alley in most places. It's an avalanche of storytelling opportunities.

SP: City of Rose is the second in a four book series of novels starring Ash McKenna. What is it like writing so many stories all centering on the same main character? In some ways, it must be comfortable, because you are so familiar with Ash, but I can also see it having its own particular set of constraints. Have you ever been frustrated with your commitment to this character?

RH: Honestly, yes, it can be a little frustrating. There are other stories I want to tell, plus I get worried that people will be less inclined to jump into a series mid-stream--which is why I try to make all the books stand alone. You can read them individually and still get a complete story, but if you read them all, you see a more complete arc. That said, I don't regret this decision. I feel like I'm working through some stuff, both personally and as a writer. And Ash is just really fun to write. His voice comes naturally to me, so even the hard parts of the process are still fun.

SP: With City of Rose and the Ash McKenna series, you've firmly established yourself as a modern noir serial author. What is it about the noir genre that you're so attracted to? Have you always been interested and/or influenced by noir in literature? How about noir in film or visual art?

RH: I've always been a fan of noir and darker stuff. I feel like you don't get the true measure of a person until they've hit rock bottom. And noir is all about rock bottom.

SP: Your third novel in the series, South Village, is due out this coming October. How do you keep up such a productive writing pace? How much time do you allow for each novel and do you take time off between works?

RH: I type fast, which helps. My wife is understanding, about giving me space. It's a lot of nights and weekends, or just finding time where I can. Recently I was touring the West Coast for City of Rose and I used the downtime to finish South Village. I don't really have a set timeframe for anything--to my mind, the book is done when it's done. I do try to build in breaks. For example, while I was writing South Village, I was also writing a novella with James Patterson. I'd finish a draft of South Village, move over to the novella, finish the draft of that, move back to South Village. It was a nice palate cleanser.

SP: In addition to this series, it seems like you've always got your hands on some other project. What else are you currently working on or preparing to work on? Anything coming out of left field?

RH: Right now I'm finishing up the novella with Patterson, which is part of his new BookShots series. That's about as left field as it gets, and it's been a lot of fun--and it's pushed me to be more mindful of things I need to be better at, like plot and pacing. I've also been making moves to get into comic books. That's the next mountain I want to climb. I signed for some comic work that got put on hold, which was a bummer, but it happens. Otherwise, I'm looking toward the fifth--and probably final--Ash novel. And the books I want to write after that.

SP: Though I'm sure you read in the genre you write, do you have any secret reading habits that would surprise your readers? Are there any unlikely books or authors who have influenced your work?

RH: I wouldn't call my reading habits secret--one of my favorite bits of advice is to read outside your chosen genre as much as possible. I read YA, erotica, literary, sci-fi... it's good to have a bubble, but if you spend too much time inside, you'll suffocate. And when you read outside your chosen genre, you're introduced to new storytelling tropes and techniques, but you find a lot of the scaffolding is the same.

SP: Finally, as always, I'd like to spread the love. Give me three upcoming novels (this year or next) that I should have my eye on.

RH: Rough Trade, the new Boo and Junior book from Todd Robinson, is fantastic. No one writes like Todd--he's got this big, booming voice that is so engaging and so unique to him. Underground Airlines by Ben Winters is brilliant--it's set in an alternate version of the United States, where slavery is still legal. I begged the editor at Mulholland for an advance reading copy-- I got it as a Word doc, before the galleys were even available. Worth it. And Down the Darkest Street, the new Pete Fernandez book by Alex Segura, is awesome. A solid entry in what I hope is a long series.

So many thanks to Rob Hart! Be sure to check out New Yorked and City of Rose , both currently available from Polis Books, and keep your eyes open for the upcoming South Village. Cheers!

Steph Post: City of Rose is the sequel to your debut with PI Ash McKenna, New Yorked. In New Yorked, the city itself was an essential character to the story and it seemed hard to imagine Ash functioning in any place else. Part of the evolution of Ash's story, though, is his move in City of Rose to Portland, Oregon. In writing this new novel, were you nervous about taking Ash out of his element? Were you concerned at all that since the city of New York is such a part of your identity of a writer, this drastic change of setting would be a jolt for readers?

Rob Hart: I was excited to take Ash out of New York. He's got this quality that's common to New York natives: That New York, and being raised there, has made them smarter and better than everyone else. It was time to dissuade him of that notion. And I needed the challenge--I wanted to get out of my own element. So in a lot of ways, me and Ash were on the same page--we were both navigating a place we weren't very familiar with. My hope is that it's exciting for the reader, too.

SP: In addition to shipping Ash all the way to the west coast, you land him in a vegan strip club. In all honesty, I found this a little startling at first. Maybe I'm old fashioned, but I'd never even heard of a vegan strip club.... Where on earth did you get the idea for this and why did you choose this as this the place where Ash ends up?

RH: Vegan strip clubs are real! Portland has at least one, maybe more. There's a law in Portland--any place that serves booze has to serve food. And they take food pretty seriously out there. I originally had him working in a coffee shop and it was okay, but not really clicking. Strip clubs in Portland are weird--the audience is usually equally male and female, at least in a lot of the ones I've been to. Going to a strip club in Portland is like going to a bowling alley in most places. It's an avalanche of storytelling opportunities.

SP: City of Rose is the second in a four book series of novels starring Ash McKenna. What is it like writing so many stories all centering on the same main character? In some ways, it must be comfortable, because you are so familiar with Ash, but I can also see it having its own particular set of constraints. Have you ever been frustrated with your commitment to this character?

RH: Honestly, yes, it can be a little frustrating. There are other stories I want to tell, plus I get worried that people will be less inclined to jump into a series mid-stream--which is why I try to make all the books stand alone. You can read them individually and still get a complete story, but if you read them all, you see a more complete arc. That said, I don't regret this decision. I feel like I'm working through some stuff, both personally and as a writer. And Ash is just really fun to write. His voice comes naturally to me, so even the hard parts of the process are still fun.

SP: With City of Rose and the Ash McKenna series, you've firmly established yourself as a modern noir serial author. What is it about the noir genre that you're so attracted to? Have you always been interested and/or influenced by noir in literature? How about noir in film or visual art?

RH: I've always been a fan of noir and darker stuff. I feel like you don't get the true measure of a person until they've hit rock bottom. And noir is all about rock bottom.

SP: Your third novel in the series, South Village, is due out this coming October. How do you keep up such a productive writing pace? How much time do you allow for each novel and do you take time off between works?

RH: I type fast, which helps. My wife is understanding, about giving me space. It's a lot of nights and weekends, or just finding time where I can. Recently I was touring the West Coast for City of Rose and I used the downtime to finish South Village. I don't really have a set timeframe for anything--to my mind, the book is done when it's done. I do try to build in breaks. For example, while I was writing South Village, I was also writing a novella with James Patterson. I'd finish a draft of South Village, move over to the novella, finish the draft of that, move back to South Village. It was a nice palate cleanser.

SP: In addition to this series, it seems like you've always got your hands on some other project. What else are you currently working on or preparing to work on? Anything coming out of left field?

RH: Right now I'm finishing up the novella with Patterson, which is part of his new BookShots series. That's about as left field as it gets, and it's been a lot of fun--and it's pushed me to be more mindful of things I need to be better at, like plot and pacing. I've also been making moves to get into comic books. That's the next mountain I want to climb. I signed for some comic work that got put on hold, which was a bummer, but it happens. Otherwise, I'm looking toward the fifth--and probably final--Ash novel. And the books I want to write after that.

SP: Though I'm sure you read in the genre you write, do you have any secret reading habits that would surprise your readers? Are there any unlikely books or authors who have influenced your work?

RH: I wouldn't call my reading habits secret--one of my favorite bits of advice is to read outside your chosen genre as much as possible. I read YA, erotica, literary, sci-fi... it's good to have a bubble, but if you spend too much time inside, you'll suffocate. And when you read outside your chosen genre, you're introduced to new storytelling tropes and techniques, but you find a lot of the scaffolding is the same.

SP: Finally, as always, I'd like to spread the love. Give me three upcoming novels (this year or next) that I should have my eye on.

RH: Rough Trade, the new Boo and Junior book from Todd Robinson, is fantastic. No one writes like Todd--he's got this big, booming voice that is so engaging and so unique to him. Underground Airlines by Ben Winters is brilliant--it's set in an alternate version of the United States, where slavery is still legal. I begged the editor at Mulholland for an advance reading copy-- I got it as a Word doc, before the galleys were even available. Worth it. And Down the Darkest Street, the new Pete Fernandez book by Alex Segura, is awesome. A solid entry in what I hope is a long series.

So many thanks to Rob Hart! Be sure to check out New Yorked and City of Rose , both currently available from Polis Books, and keep your eyes open for the upcoming South Village. Cheers!

Published on March 29, 2016 09:15

March 18, 2016

March Book Bites! (Tasty Reviews for Your Reading Pleasure)

This was a pretty eclectic reading month for me, but here are my four top book recommendations. Enjoy!

Ways to DisappearA quirky, fast-paced and engaging read. Against the lush backdrop of Brazil and the world of authors, editors and translators, Ways to Disappear explores the different ways to look at art and perspective (and does so with a noir storyline to make it even crazier...). Available now.

All the Light We Cannot SeeAn all encompassing, absorbing tale that telescopes back and forth through time and across spaces both great and small. Its story is powerful and quietly commanding. I can't believe it's taken me this long to pick up this gem! Available now.

Olive KitteridgeHere's another book I'm kicking myself for not having read sooner. Olive Kitteridge, though seemingly unassuming, is one of the best literary novels I've read in a long time. Elizabeth Strout is one of those writers that actually does manage to take a reader's breath away. Available now.

This is Not a ConfessionDavid Olimpio's essay collection is a brutally honest memoir, but also an excavation and examination of the power of memory and its creative potential. To learn more, check out my interview with the author as we discuss everything from unreliable narrators to philosophy to science. Available April 22nd.

Ways to DisappearA quirky, fast-paced and engaging read. Against the lush backdrop of Brazil and the world of authors, editors and translators, Ways to Disappear explores the different ways to look at art and perspective (and does so with a noir storyline to make it even crazier...). Available now.

All the Light We Cannot SeeAn all encompassing, absorbing tale that telescopes back and forth through time and across spaces both great and small. Its story is powerful and quietly commanding. I can't believe it's taken me this long to pick up this gem! Available now.

Olive KitteridgeHere's another book I'm kicking myself for not having read sooner. Olive Kitteridge, though seemingly unassuming, is one of the best literary novels I've read in a long time. Elizabeth Strout is one of those writers that actually does manage to take a reader's breath away. Available now.

This is Not a ConfessionDavid Olimpio's essay collection is a brutally honest memoir, but also an excavation and examination of the power of memory and its creative potential. To learn more, check out my interview with the author as we discuss everything from unreliable narrators to philosophy to science. Available April 22nd.

Published on March 18, 2016 08:55

March 14, 2016

Not a Confession- A Conversation. (With Author David Olimpio)

On April 22nd, Awst Press will be releasing David Olimpio's memoir/essay collection

This is Not a Confession

. Though not for everyone, (there are quite a few graphic descriptions of sexual abuse- I want to make that clear) Olimpio's debut is both startling and accomplished. In brash and brutally honest form Olimpio delves into uncomfortable issues ranging from traumatic childhood events to coping with his mother's death to his somewhat unconventional adult life. In each of these essays, Olimpio explores both the facts and perceptions surrounding the incident with an uncompromising lens. This is Not a Confession goes beyond autobiography or memoir, however, as it also explores the relationship Olimpio has with memory and with the process of uncovering and crafting memory.

With this interview, David Olimpio digs even deeper as we discuss unreliable narrators, logic and existentialism through memory. Read on.

Steph Post: I'm going to jump right in with the title of your essay collection- This is Not a Confession. The theme of confessing, or rather, not confessing, comes up throughout the pieces as does your declaration that you can't be shamed. Yet at first glance, this book reads exactly like a confession, as it hallmarked by a painfully honest tone. Can you explain how it is not? Why is the concept of confessing so important to your work?

David Olimpio: I think I've always been enamored with unreliable narrators. And it turns out I am also most enamored with myself as narrator when I am somewhat unreliable. So I think, in part, the title has something to do with that. I like when somebody says one thing but means something else. Not in an untruthful sort of way, but in a knowing sort of way. As in, we all know what’s really being said. Because another word to describe "saying one thing but meaning something else" is that it’s a lie. But I've never been good at lying. I think I might be genetically incapable of it. Which has made my fiction-writing attempts a real pain in the ass.

So you're absolutely right: this book is definitely a confession. The line "this isn't a confession" comes out of one of the stories during a conversation with my wife. Confessions often connote an apology, though. And the act of confessing in that story, as well as in the other stories in this book, are not that. They are not apologies.

I spent most of my life feeling shame over a lot of the things I write about in the book. And I'm done with that. Part of the reason I'm done with it is because speaking about the things has made the shame over them disappear. That's one of the themes in the book: how voicing the things you're feeling shame about has a way of taking that shame away.

But one of the things I didn't want was for this to come across as any sort of apology for having done the things or for having been involved in the things. There is no regret or feelings of sorrow for the things having happened. Those things both are and aren't me and I wouldn't change any of them, even if I could. I hope that’s conveyed by the title.

By the way, this wasn’t my original idea for the title of the book. I had originally wanted to call it Shirts and Skins. Or These Not Quite Sleeping Dogs. I believe Tatiana Ryckman is the one who suggested This Is Not a Confession and the others at Awst Press thought that was the best one. They were right.

SP: The book is composed of four sections, each made up of several essays, many of which are broken down into further sections. Does this breaking down and compartmentalizing of the text have any relationship to how memory works or how an author must approach memory when writing autobiographically?

DO: The sections sort of evolved on their own and with the help of the editors at Awst Press. I wrote a whole blog post about how much their input helped shape the book.

I do think you might be on to something about that structure sort of mirroring how memory works. The book opens with stories about my mother and her death, which was something at the forefront of my mind for much of the last five years. The interesting thing about that is that my mother's death sparked the writing of most of the rest of the stories in the book. And so in that way it makes sense for this section to be first in the book. Because without her death, the stories might never have happened, either in real life, or on the page.

I might never have written stories about me being molested when I was five and six if my mother hadn't died. Because I never wanted to tell her about it. Partly because of my own shame, but partly because it would have broken her heart. So the story of that stuff happening to me as a child became wrapped up in the story of her death, which was a weird thing to have happen, but was also a very honest and truthful thing.

I've never been drawn to linear stories because memory doesn't work that way. At the same time, an author has to make the stories make some kind of sense—that’s the author's job in this whole writing game, especially in nonfiction. There is a lot of memoir out there that basically amounts to this: "Here are a bunch of things that happened to me, and well, ain't it some shit?" It isn't enough to do that. You have to tell the reader why it matters. You have to tell the reader what it means. If you haven't done that, then you've missed the whole point and you haven't done the hard work and you'd probably be better off selling cars or tending bar or something where you can at least make some money.

SP: Especially in the first section, many of the essays are riddled with references to time, numbers and physics. You mention Einstein a few times and also cite stories which have appeared on the science-oriented podcast Radiolab. Where does this science influence come from?

DO: In school I never really liked math. But the reason I didn't like math was not because I wasn't good at it. I could do math just fine. I got good grades in it. The thing I didn't like about math was that I never really understood why I was doing it. I didn't understand why it mattered.

In college I took an advanced math class that wasn't so much about memorizing and applying formulas; instead it was all conceptual. It was a class on symmetry and how symmetrical patterns were things that could be found everywhere in nature and maybe, just maybe, this held some sort of answer to life. This spoke to me. Here was a reason why math mattered. Numbers could be the answer. They could be the answer to everything.

I am also heavily into philosophy and people who like philosophy are usually people who like logic and numbers. I like Wittgenstein a lot because he takes logic problems and makes them, essentially, problems about language. All problems are really just problems of language. If we don't have an answer to them, it’s because we don't have the right words.

Juxtaposing the scientific with the personal is probably my way of trying to get at some deeper meaning that I feel is out there but can’t quite find, because I don’t have the language for it yet. I wish I had a better head for science because then I might be able to arrive at something truly important or groundbreaking. But I guess it's enough for me to just skip a rock over the ocean body of mysteries. It's all my brain is capable of.

SP: Without going into the details explicitly described in many of the essays, there is some tough material for readers to get through in This is Not a Confession. In many ways, your book has "trigger warning" written all over it and, to be honest, I had a rough time getting through the many personal accounts of your childhood sexual trauma and abuse. I very much admire the strength and candidness of your writing, but have you ever worried about either hurting or alienating readers?

DO: My main concern wasn't so much over the childhood sex stuff, as it was over some of the graphic sexual material from my adult life. I know there are probably members of my family, for instance, who will not want to read that shit. Not for the reasons you've mentioned, but simply because they will have absolutely no interest in reading graphic sex scenes, especially ones with me in them.

But I didn't write this for them. I would say that I didn't write it for anybody but me, but that's not really true. I think any writer who makes that kind of statement is either lying or deluded or both.

I wrote it for me, but I also know there is an audience for this book. There are people who will absolutely love this book. That feels cocky for me to say, but I don’t mean it in that way. I just know that there are things I write about in this book that somebody out there is dying to hear somebody talk about. There are people out there who would be interested to read an account of a man who has been raped by another man as a child, and who would be interested to know what that man thinks about it. You don't find that story written about very often. It's not a buzz topic on all the literary sites. Not because it doesn't happen, or because it isn’t an issue, but because men don't tend to talk about it.

Likewise, there are people out there who would love for somebody to write honestly about polyamory and making that work within the context of a long-term, committed relationship of 15+ years. And to approach that subject on the page in a way that goes beyond the low-hanging fruit of jealousy and breakup and divorce. To write a narrative about it that doesn’t try to pathologize it, or begin with the premise that it is a problem of some kind.

I think there are people who will relate to this book and who will say "fuck yes." I think it will resonate with a certain audience and my sincere hope is to find that audience.

I do worry that the book may alienate some of the people who have come to know me primarily through my dog photo blog. But I also know this: many of those people aren't going to read a book I write no matter what it's about. And so worrying about their reaction to it is a waste of time. And the fact of the matter is, they may read it and love it and never tell me about it. You just don’t know.

Still, if I’m being honest, I can think of dozens of people who, if I think too hard about them reading the book, it makes me cringe. I worry about their reaction to it, and I understand that I may in fact alienate those people. But in the end, I'm more excited over the prospect of the readers I might gain by writing a book like this than I am worried about the ones I'm going to alienate.

SP: At the end of your essay "The Big Bad Wolf," there are some lines that really struck me as being central to both this collection and your style. You write: "We create memories; they do not create us. And the more we remember a thing... The less we hide from it. The less power we give it to control us." How did you come to think about memory in this way? Why is it important to you both to share your memories and this philosophy with readers?

DO: I think the main reason I write at all is to try to find answers to the questions "Who Am I?" and "Why am I?" Writing, for me, will always be about trying to arrive at some sort of existential meaning, whether the narrative form is nonfiction, as it is in this book, or fiction. Regardless of which tact I take (fiction/nonfiction) I always will aim to do that.

I’m not a fan of the passive voice in personal narrative. Where there is a lot of talk of an “other” or of an event that happened to the person telling the story. ”Such and such happened to me." "So and so did this to me.”

No. I did this. I partook in this.

What I’ve found is that when I don’t talk about an important thing in my life, especially traumatic things, the thing holds a power over me. As soon as I work at remembering it and telling it, the thing becomes a lot less mysterious and abstract and powerful. You see it for what it is: just a thing that happened in a world full of things that happen. And it eventually turns into a less scary thing. That was probably the main point to “Big Bad Wolf.”

I don't want my memories to be “things that happened to me.” I want my memories to be exactly what they are: Things I make. There is science behind the notion that the act of remembering something is inherently an act of creation. I love that. I want to own my memories. I don’t want to hide from them or treat them as fucking precious things by either skirting around them or trying to uncover every single supposed fact about them.

This is one of the reasons I'm skeptical of any memoir that is very tied to the details of what happened, as if those details convey some kind of truth about the thing. There is no empirical truth to a thing that happened in our lives. There is only our truth to it. Except in regards to science and numbers and math. I suppose there can be truth in those things. (Ah! It’s all coming back to science, isn’t it?)

Life happens in those memories. Humanness happens in those memories. And we are all human and we are all a part of life. None of us are any more or less than human.

SP: I don't often read memoirs or personal essay collections, but I'm intrigued by the genre the way you write it. Who or what else would you recommend for readers interested in this style?

DO: I don't know if the books I'm about to mention are necessarily "in this style." If I were to suggest that my book was in the same playground or sandbox as these, I would probably be taken as egotistical at best or an outright liar at worst. But there are three that come to mind. When I read these, I didn't think of them so much as “nonfiction essay" or “memoir” as I did a story or set of stories which, among other things, didn't profess to be fiction. And I really liked that about them.

Maggie Nelson: Bluets

Tim Kreider: We Learn Nothing

And because I can't seem to recommend anything without one of the things being a Martin Amis book, I'd say: Experience .

Many thanks to David Olimpio! As a reminder, This is Not a Confession drops on April 22nd. If you're in the Dallas area, be sure to hit up the launch party on the 23rd at Deep Vellum Books, 7pm. And, of course, if This is Not a Confession piques your interest, be sure to buy, read, review and recommend. Cheers!

With this interview, David Olimpio digs even deeper as we discuss unreliable narrators, logic and existentialism through memory. Read on.

Steph Post: I'm going to jump right in with the title of your essay collection- This is Not a Confession. The theme of confessing, or rather, not confessing, comes up throughout the pieces as does your declaration that you can't be shamed. Yet at first glance, this book reads exactly like a confession, as it hallmarked by a painfully honest tone. Can you explain how it is not? Why is the concept of confessing so important to your work?

David Olimpio: I think I've always been enamored with unreliable narrators. And it turns out I am also most enamored with myself as narrator when I am somewhat unreliable. So I think, in part, the title has something to do with that. I like when somebody says one thing but means something else. Not in an untruthful sort of way, but in a knowing sort of way. As in, we all know what’s really being said. Because another word to describe "saying one thing but meaning something else" is that it’s a lie. But I've never been good at lying. I think I might be genetically incapable of it. Which has made my fiction-writing attempts a real pain in the ass.

So you're absolutely right: this book is definitely a confession. The line "this isn't a confession" comes out of one of the stories during a conversation with my wife. Confessions often connote an apology, though. And the act of confessing in that story, as well as in the other stories in this book, are not that. They are not apologies.

I spent most of my life feeling shame over a lot of the things I write about in the book. And I'm done with that. Part of the reason I'm done with it is because speaking about the things has made the shame over them disappear. That's one of the themes in the book: how voicing the things you're feeling shame about has a way of taking that shame away.

But one of the things I didn't want was for this to come across as any sort of apology for having done the things or for having been involved in the things. There is no regret or feelings of sorrow for the things having happened. Those things both are and aren't me and I wouldn't change any of them, even if I could. I hope that’s conveyed by the title.

By the way, this wasn’t my original idea for the title of the book. I had originally wanted to call it Shirts and Skins. Or These Not Quite Sleeping Dogs. I believe Tatiana Ryckman is the one who suggested This Is Not a Confession and the others at Awst Press thought that was the best one. They were right.

SP: The book is composed of four sections, each made up of several essays, many of which are broken down into further sections. Does this breaking down and compartmentalizing of the text have any relationship to how memory works or how an author must approach memory when writing autobiographically?

DO: The sections sort of evolved on their own and with the help of the editors at Awst Press. I wrote a whole blog post about how much their input helped shape the book.

I do think you might be on to something about that structure sort of mirroring how memory works. The book opens with stories about my mother and her death, which was something at the forefront of my mind for much of the last five years. The interesting thing about that is that my mother's death sparked the writing of most of the rest of the stories in the book. And so in that way it makes sense for this section to be first in the book. Because without her death, the stories might never have happened, either in real life, or on the page.

I might never have written stories about me being molested when I was five and six if my mother hadn't died. Because I never wanted to tell her about it. Partly because of my own shame, but partly because it would have broken her heart. So the story of that stuff happening to me as a child became wrapped up in the story of her death, which was a weird thing to have happen, but was also a very honest and truthful thing.

I've never been drawn to linear stories because memory doesn't work that way. At the same time, an author has to make the stories make some kind of sense—that’s the author's job in this whole writing game, especially in nonfiction. There is a lot of memoir out there that basically amounts to this: "Here are a bunch of things that happened to me, and well, ain't it some shit?" It isn't enough to do that. You have to tell the reader why it matters. You have to tell the reader what it means. If you haven't done that, then you've missed the whole point and you haven't done the hard work and you'd probably be better off selling cars or tending bar or something where you can at least make some money.

SP: Especially in the first section, many of the essays are riddled with references to time, numbers and physics. You mention Einstein a few times and also cite stories which have appeared on the science-oriented podcast Radiolab. Where does this science influence come from?

DO: In school I never really liked math. But the reason I didn't like math was not because I wasn't good at it. I could do math just fine. I got good grades in it. The thing I didn't like about math was that I never really understood why I was doing it. I didn't understand why it mattered.

In college I took an advanced math class that wasn't so much about memorizing and applying formulas; instead it was all conceptual. It was a class on symmetry and how symmetrical patterns were things that could be found everywhere in nature and maybe, just maybe, this held some sort of answer to life. This spoke to me. Here was a reason why math mattered. Numbers could be the answer. They could be the answer to everything.

I am also heavily into philosophy and people who like philosophy are usually people who like logic and numbers. I like Wittgenstein a lot because he takes logic problems and makes them, essentially, problems about language. All problems are really just problems of language. If we don't have an answer to them, it’s because we don't have the right words.

Juxtaposing the scientific with the personal is probably my way of trying to get at some deeper meaning that I feel is out there but can’t quite find, because I don’t have the language for it yet. I wish I had a better head for science because then I might be able to arrive at something truly important or groundbreaking. But I guess it's enough for me to just skip a rock over the ocean body of mysteries. It's all my brain is capable of.

SP: Without going into the details explicitly described in many of the essays, there is some tough material for readers to get through in This is Not a Confession. In many ways, your book has "trigger warning" written all over it and, to be honest, I had a rough time getting through the many personal accounts of your childhood sexual trauma and abuse. I very much admire the strength and candidness of your writing, but have you ever worried about either hurting or alienating readers?

DO: My main concern wasn't so much over the childhood sex stuff, as it was over some of the graphic sexual material from my adult life. I know there are probably members of my family, for instance, who will not want to read that shit. Not for the reasons you've mentioned, but simply because they will have absolutely no interest in reading graphic sex scenes, especially ones with me in them.

But I didn't write this for them. I would say that I didn't write it for anybody but me, but that's not really true. I think any writer who makes that kind of statement is either lying or deluded or both.

I wrote it for me, but I also know there is an audience for this book. There are people who will absolutely love this book. That feels cocky for me to say, but I don’t mean it in that way. I just know that there are things I write about in this book that somebody out there is dying to hear somebody talk about. There are people out there who would be interested to read an account of a man who has been raped by another man as a child, and who would be interested to know what that man thinks about it. You don't find that story written about very often. It's not a buzz topic on all the literary sites. Not because it doesn't happen, or because it isn’t an issue, but because men don't tend to talk about it.

Likewise, there are people out there who would love for somebody to write honestly about polyamory and making that work within the context of a long-term, committed relationship of 15+ years. And to approach that subject on the page in a way that goes beyond the low-hanging fruit of jealousy and breakup and divorce. To write a narrative about it that doesn’t try to pathologize it, or begin with the premise that it is a problem of some kind.

I think there are people who will relate to this book and who will say "fuck yes." I think it will resonate with a certain audience and my sincere hope is to find that audience.

I do worry that the book may alienate some of the people who have come to know me primarily through my dog photo blog. But I also know this: many of those people aren't going to read a book I write no matter what it's about. And so worrying about their reaction to it is a waste of time. And the fact of the matter is, they may read it and love it and never tell me about it. You just don’t know.

Still, if I’m being honest, I can think of dozens of people who, if I think too hard about them reading the book, it makes me cringe. I worry about their reaction to it, and I understand that I may in fact alienate those people. But in the end, I'm more excited over the prospect of the readers I might gain by writing a book like this than I am worried about the ones I'm going to alienate.

SP: At the end of your essay "The Big Bad Wolf," there are some lines that really struck me as being central to both this collection and your style. You write: "We create memories; they do not create us. And the more we remember a thing... The less we hide from it. The less power we give it to control us." How did you come to think about memory in this way? Why is it important to you both to share your memories and this philosophy with readers?

DO: I think the main reason I write at all is to try to find answers to the questions "Who Am I?" and "Why am I?" Writing, for me, will always be about trying to arrive at some sort of existential meaning, whether the narrative form is nonfiction, as it is in this book, or fiction. Regardless of which tact I take (fiction/nonfiction) I always will aim to do that.

I’m not a fan of the passive voice in personal narrative. Where there is a lot of talk of an “other” or of an event that happened to the person telling the story. ”Such and such happened to me." "So and so did this to me.”

No. I did this. I partook in this.

What I’ve found is that when I don’t talk about an important thing in my life, especially traumatic things, the thing holds a power over me. As soon as I work at remembering it and telling it, the thing becomes a lot less mysterious and abstract and powerful. You see it for what it is: just a thing that happened in a world full of things that happen. And it eventually turns into a less scary thing. That was probably the main point to “Big Bad Wolf.”

I don't want my memories to be “things that happened to me.” I want my memories to be exactly what they are: Things I make. There is science behind the notion that the act of remembering something is inherently an act of creation. I love that. I want to own my memories. I don’t want to hide from them or treat them as fucking precious things by either skirting around them or trying to uncover every single supposed fact about them.

This is one of the reasons I'm skeptical of any memoir that is very tied to the details of what happened, as if those details convey some kind of truth about the thing. There is no empirical truth to a thing that happened in our lives. There is only our truth to it. Except in regards to science and numbers and math. I suppose there can be truth in those things. (Ah! It’s all coming back to science, isn’t it?)

Life happens in those memories. Humanness happens in those memories. And we are all human and we are all a part of life. None of us are any more or less than human.

SP: I don't often read memoirs or personal essay collections, but I'm intrigued by the genre the way you write it. Who or what else would you recommend for readers interested in this style?

DO: I don't know if the books I'm about to mention are necessarily "in this style." If I were to suggest that my book was in the same playground or sandbox as these, I would probably be taken as egotistical at best or an outright liar at worst. But there are three that come to mind. When I read these, I didn't think of them so much as “nonfiction essay" or “memoir” as I did a story or set of stories which, among other things, didn't profess to be fiction. And I really liked that about them.

Maggie Nelson: Bluets

Tim Kreider: We Learn Nothing

And because I can't seem to recommend anything without one of the things being a Martin Amis book, I'd say: Experience .

Many thanks to David Olimpio! As a reminder, This is Not a Confession drops on April 22nd. If you're in the Dallas area, be sure to hit up the launch party on the 23rd at Deep Vellum Books, 7pm. And, of course, if This is Not a Confession piques your interest, be sure to buy, read, review and recommend. Cheers!

Published on March 14, 2016 16:14

February 22, 2016

Consider the Octopus: An Interview with Elizabeth Gonzalez

One of the most interesting and unique books I've read as of late is Elizabeth Gonzalez's

The Universal Physics of Escape

from Press 53. The short story collection is tied together by tales richly infused with science which, of course, is right up my alley (being the huge Sam Kean and other science writers fan that I am....). You can read my full account of the book over at Small Press Book Review, but today I bring you an interview with Gonzalez herself. Enjoy!

Steph Post: All of the stories in The Universal Physics of Escape contain some reference to science. Additionally, the themes of loneliness, death and religion are prevalent in most works and overall this collection appears to be a cohesive body of work. I’m interested in how this collection came about. Did you write these stories intending for them to one day be compiled in a book or did you see the common threads running through afterwards and then decide to develop a collection?

Elizabeth Gonzalez: Basically, to create the collection, I pulled together all of the stories I had that had worked out. I’m not a prolific writer and it was a feat for me to assemble enough finished work to create a collection at all. I had gathered some of the stories for my master’s thesis seven years ago, and I was surprised then to see then how connected they were. Collecting stories gives you a new, larger perspective on what’s eating you, what makes you write.

I was working on the final story, "Universal Physics," as I assembled the collection. I was struck by the line connecting the titles of the short shorts – "0 = 1," "Here," "Departure," "Trajectories." That was just weird, an artifact of something. "Here" and "Departure" formed their own sort of line of thinking that came together very concretely in the final story. That moment—when those threads of very disparate stories came together in a handful of lines—is the one that told me the collection was done. It’s the same way it works in a story—you have that line on which the whole matter hinges. You hit it and know you have a story.

By far, that is the most exciting aspect of writing for me. The work really does write back, if you work through it long enough, and give it enough time to resolve.

SP: As a lover of science writing in its own right, I was excited to see a short story collection built upon themes of astronomy, physics and the natural sciences. What drew you to incorporating scientific formulas, images and concepts into your fiction work? While I certainly appreciated the motif, do you think there is a risk of alienating some readers?

EG: I think it’s a case of writing what you read and think about. I love lay science. It reveals reality to me. I read science to try to understand on a very fundamental level what I am, what to make of my time on the planet, what life is. Sometimes, something happens that bounces into a story. I see a line between something I’m obsessing over and a character, and I start writing.

I do think there’s a huge risk of alienating people. I guess I feel about it generally the way I feel about my hair: it’s unfortunate, but I’m stuck with it. But I am very aware of that possibility. This is a challenging market, and just on a sort of hostess level, you never want to abuse a ready reader. So the fact that it’s in there means I have no other choice. It is how it has to be said. When someone like you reads it and likes it, I have to say, I choke up. No exaggeration. When someone reads it at all, I am amazed.

SP: Oftentimes, religion and scientific thought are seen as being odds with one another. In your stories, however, I found these themes flowing together seamlessly. How do you think science and religion are connected? Is this something that you deliberately set out to explore in your writing?

EG: I think religion and science are absolutely, intimately, inextricably connected. It is one of the great sorrows of our time that their discussions are so polarized and mutually deaf. I think endlessly, tirelessly, about what it means to be here. So I think endlessly about religion and origins and ends and science. They’re all the same question, the same quest, to me. I hate partisanship of all stripes, and this sort especially. Because it prevents people from hearing one another. And it prevents some of the most interesting discussions, I think, that people could have.

Richard Dawkins writes beautifully about the incredible privilege of seeing a day on the planet. About the overwhelming odds against having that experience at any given moment in the universe. He happens to be an atheist, and has become a champion of that world view. But he’s probing the same questions that writers like C.S. Lewis and Soren Kierkegaard wrestled with. And the jury’s still out, right? We have to answer these questions for ourselves.

SP: Most of the pieces in The Universal Physics of Escape fit the structure of what readers would easily recognize as stories. I wanted to ask you about “Departure,” though. For me, this is the piece that borders on the abstract. It’s not a prose poem, but it doesn’t necessarily have all of the elements of a story. How would you describe this work? Is there a story somewhere buried somewhere beneath the reflective layers that I’ve missed? And does it even matter if “Departure” is a traditional story or not?

EG: It’s funny, the version of this story in the collection is one I fleshed out from a story I wrote for my thesis. The original had even less character and plot resolution, and the very smart people I went to school with said it needed more of that traditional “story.” I resisted for years, then finally, after a couple of editors made similar comments in rejections, I fleshed out some of those elements. I sold it shortly after. It’s my personal case study for when to listen to editorial suggestions (consensus is a good sign). Probably part of my resistance is personal. Maybe it could be more resolved. I guess I quit when I sold it.

SP: I’ve already mentioned that the themes of loneliness and death pervade your work. There is also a haunting sense of isolation in many of your stories. Is all of your work infused with some form of melancholia? Or are your stories not sad, but something else entirely?

EG: There is a tremendous isolation in the stories. That was something that really struck me when I pulled them together, how alone the characters are, down to the last. That was definitely a case of self-revelation. I wish it were not so. You don’t pick your themes. At least, that’s my experience.

When I was a kid, I always assumed I was isolated from moving around all the time. When I got older, I viewed this as a problem to solve and moved to the suburbs. I guess my work revealed to me the issue may go beyond where I live, as I’ve been in the same place now for 22 years. I’d probably have to write for ten more years to figure out the next glaringly obvious thing about my life that anyone on the street could see in five minutes. Apparently this is how it works.

SP: One of the things I found most interesting about your stories is the use of animals. I found their inclusion not to be typically symbolic, however, but rather a way of giving voice to emotions and ideas otherwise inexpressible. Can you explain how you intended animals to function in The Universal Physics of Escape?

EG: Honestly, you had a line in your review that really struck me, about the elements of the stories working as “voices.” I’d never seen it in quite that light, and I really like that terminology. The octopuses and herons and crows aren’t things I put in to enhance the stories, or to signify for someone else. They are the stories. The story "Universal Physics" is as much about real living octopuses in the depths of the ocean as it is about middle-aged mothers in the depths of suburbia. The collection is all about bats that will dive for a stone, and moths that fry themselves because they thought they saw the moon, and the weather coming unhinged, and arms that can run away when severed. This is a wondrous and terrible planet.

SP: And finally, I have to ask: why the octopus?

EG: I met a little white octopus in a science museum on Tybee Island, South Carolina about ten years ago. It latched onto the glass and followed my hand wherever I moved it, and that made me sad. That little guy prompted years of reading and exploration, and the more I read, the more I was struck by the similarities between the octopus and myself, or my kind. And—and here’s the part I don’t think maybe people understand—it wasn’t a case of making a case for connection, of writing to create a parallel. It was a case of seeing the connections that exist, of taking down evidence—of writing, very simply, what is.

So many thanks to Elizabeth Gonzalez. Be sure to order and read The Universal Physics of Escape - and while you're at, check out some of the other great collections from Press 53. There's quite a lot of talent coming from that direction.... Cheers!

Steph Post: All of the stories in The Universal Physics of Escape contain some reference to science. Additionally, the themes of loneliness, death and religion are prevalent in most works and overall this collection appears to be a cohesive body of work. I’m interested in how this collection came about. Did you write these stories intending for them to one day be compiled in a book or did you see the common threads running through afterwards and then decide to develop a collection?

Elizabeth Gonzalez: Basically, to create the collection, I pulled together all of the stories I had that had worked out. I’m not a prolific writer and it was a feat for me to assemble enough finished work to create a collection at all. I had gathered some of the stories for my master’s thesis seven years ago, and I was surprised then to see then how connected they were. Collecting stories gives you a new, larger perspective on what’s eating you, what makes you write.

I was working on the final story, "Universal Physics," as I assembled the collection. I was struck by the line connecting the titles of the short shorts – "0 = 1," "Here," "Departure," "Trajectories." That was just weird, an artifact of something. "Here" and "Departure" formed their own sort of line of thinking that came together very concretely in the final story. That moment—when those threads of very disparate stories came together in a handful of lines—is the one that told me the collection was done. It’s the same way it works in a story—you have that line on which the whole matter hinges. You hit it and know you have a story.

By far, that is the most exciting aspect of writing for me. The work really does write back, if you work through it long enough, and give it enough time to resolve.

SP: As a lover of science writing in its own right, I was excited to see a short story collection built upon themes of astronomy, physics and the natural sciences. What drew you to incorporating scientific formulas, images and concepts into your fiction work? While I certainly appreciated the motif, do you think there is a risk of alienating some readers?

EG: I think it’s a case of writing what you read and think about. I love lay science. It reveals reality to me. I read science to try to understand on a very fundamental level what I am, what to make of my time on the planet, what life is. Sometimes, something happens that bounces into a story. I see a line between something I’m obsessing over and a character, and I start writing.

I do think there’s a huge risk of alienating people. I guess I feel about it generally the way I feel about my hair: it’s unfortunate, but I’m stuck with it. But I am very aware of that possibility. This is a challenging market, and just on a sort of hostess level, you never want to abuse a ready reader. So the fact that it’s in there means I have no other choice. It is how it has to be said. When someone like you reads it and likes it, I have to say, I choke up. No exaggeration. When someone reads it at all, I am amazed.

SP: Oftentimes, religion and scientific thought are seen as being odds with one another. In your stories, however, I found these themes flowing together seamlessly. How do you think science and religion are connected? Is this something that you deliberately set out to explore in your writing?

EG: I think religion and science are absolutely, intimately, inextricably connected. It is one of the great sorrows of our time that their discussions are so polarized and mutually deaf. I think endlessly, tirelessly, about what it means to be here. So I think endlessly about religion and origins and ends and science. They’re all the same question, the same quest, to me. I hate partisanship of all stripes, and this sort especially. Because it prevents people from hearing one another. And it prevents some of the most interesting discussions, I think, that people could have.

Richard Dawkins writes beautifully about the incredible privilege of seeing a day on the planet. About the overwhelming odds against having that experience at any given moment in the universe. He happens to be an atheist, and has become a champion of that world view. But he’s probing the same questions that writers like C.S. Lewis and Soren Kierkegaard wrestled with. And the jury’s still out, right? We have to answer these questions for ourselves.

SP: Most of the pieces in The Universal Physics of Escape fit the structure of what readers would easily recognize as stories. I wanted to ask you about “Departure,” though. For me, this is the piece that borders on the abstract. It’s not a prose poem, but it doesn’t necessarily have all of the elements of a story. How would you describe this work? Is there a story somewhere buried somewhere beneath the reflective layers that I’ve missed? And does it even matter if “Departure” is a traditional story or not?

EG: It’s funny, the version of this story in the collection is one I fleshed out from a story I wrote for my thesis. The original had even less character and plot resolution, and the very smart people I went to school with said it needed more of that traditional “story.” I resisted for years, then finally, after a couple of editors made similar comments in rejections, I fleshed out some of those elements. I sold it shortly after. It’s my personal case study for when to listen to editorial suggestions (consensus is a good sign). Probably part of my resistance is personal. Maybe it could be more resolved. I guess I quit when I sold it.

SP: I’ve already mentioned that the themes of loneliness and death pervade your work. There is also a haunting sense of isolation in many of your stories. Is all of your work infused with some form of melancholia? Or are your stories not sad, but something else entirely?

EG: There is a tremendous isolation in the stories. That was something that really struck me when I pulled them together, how alone the characters are, down to the last. That was definitely a case of self-revelation. I wish it were not so. You don’t pick your themes. At least, that’s my experience.

When I was a kid, I always assumed I was isolated from moving around all the time. When I got older, I viewed this as a problem to solve and moved to the suburbs. I guess my work revealed to me the issue may go beyond where I live, as I’ve been in the same place now for 22 years. I’d probably have to write for ten more years to figure out the next glaringly obvious thing about my life that anyone on the street could see in five minutes. Apparently this is how it works.

SP: One of the things I found most interesting about your stories is the use of animals. I found their inclusion not to be typically symbolic, however, but rather a way of giving voice to emotions and ideas otherwise inexpressible. Can you explain how you intended animals to function in The Universal Physics of Escape?

EG: Honestly, you had a line in your review that really struck me, about the elements of the stories working as “voices.” I’d never seen it in quite that light, and I really like that terminology. The octopuses and herons and crows aren’t things I put in to enhance the stories, or to signify for someone else. They are the stories. The story "Universal Physics" is as much about real living octopuses in the depths of the ocean as it is about middle-aged mothers in the depths of suburbia. The collection is all about bats that will dive for a stone, and moths that fry themselves because they thought they saw the moon, and the weather coming unhinged, and arms that can run away when severed. This is a wondrous and terrible planet.

SP: And finally, I have to ask: why the octopus?

EG: I met a little white octopus in a science museum on Tybee Island, South Carolina about ten years ago. It latched onto the glass and followed my hand wherever I moved it, and that made me sad. That little guy prompted years of reading and exploration, and the more I read, the more I was struck by the similarities between the octopus and myself, or my kind. And—and here’s the part I don’t think maybe people understand—it wasn’t a case of making a case for connection, of writing to create a parallel. It was a case of seeing the connections that exist, of taking down evidence—of writing, very simply, what is.

So many thanks to Elizabeth Gonzalez. Be sure to order and read The Universal Physics of Escape - and while you're at, check out some of the other great collections from Press 53. There's quite a lot of talent coming from that direction.... Cheers!

Published on February 22, 2016 14:54

February 20, 2016

Book Bites: February Recommended Reading

Here we go! Your bite-sized reviews for the month of February...... Enjoy!

The Tsar of Love and Techno by Anthony Marra

Marra's ability to dig beneath the surface and find the jewels, the moments, that define an individual and then present those experiences as a universal experience is breathtaking. Available now. The Longest Night by Andria Williams

A tense and powerful domestic drama in the vein of Richard Yates' Revolutionary Road. Available now. The Universal Physics of Escape by Elizabeth Gonzalez At times whimsical, at times rife with the echoes of loneliness and isolation, Gonzalez's collection explores difficult human emotions through stories built on nature, physics, astronomy and religion. Read my full review at Small Press Book Review. Available now. Far Beyond the Pale by Daren Dean

At times whimsical, at times rife with the echoes of loneliness and isolation, Gonzalez's collection explores difficult human emotions through stories built on nature, physics, astronomy and religion. Read my full review at Small Press Book Review. Available now. Far Beyond the Pale by Daren Dean

Gritty, with an unscrupulous dedication to authenticity, Far Beyond the Pale is a tense tale told in an uncompromising voice. Available now. Find Me by Laura Van Den Berg

Gritty, with an unscrupulous dedication to authenticity, Far Beyond the Pale is a tense tale told in an uncompromising voice. Available now. Find Me by Laura Van Den Berg

A haunting, surreal story of a young woman attempting to come to grips with her identity in a world that more closely mirrors the convolutions of her mind than a place we would readily recognize. Available now.

The Tsar of Love and Techno by Anthony Marra

Marra's ability to dig beneath the surface and find the jewels, the moments, that define an individual and then present those experiences as a universal experience is breathtaking. Available now. The Longest Night by Andria Williams

A tense and powerful domestic drama in the vein of Richard Yates' Revolutionary Road. Available now. The Universal Physics of Escape by Elizabeth Gonzalez

At times whimsical, at times rife with the echoes of loneliness and isolation, Gonzalez's collection explores difficult human emotions through stories built on nature, physics, astronomy and religion. Read my full review at Small Press Book Review. Available now. Far Beyond the Pale by Daren Dean

At times whimsical, at times rife with the echoes of loneliness and isolation, Gonzalez's collection explores difficult human emotions through stories built on nature, physics, astronomy and religion. Read my full review at Small Press Book Review. Available now. Far Beyond the Pale by Daren Dean

Gritty, with an unscrupulous dedication to authenticity, Far Beyond the Pale is a tense tale told in an uncompromising voice. Available now. Find Me by Laura Van Den Berg

Gritty, with an unscrupulous dedication to authenticity, Far Beyond the Pale is a tense tale told in an uncompromising voice. Available now. Find Me by Laura Van Den Berg

A haunting, surreal story of a young woman attempting to come to grips with her identity in a world that more closely mirrors the convolutions of her mind than a place we would readily recognize. Available now.

Published on February 20, 2016 07:08

February 12, 2016

Review of The Universal Physics of Escape by Elizabeth Gonzalez

I've got a new book review over at Small Press Book Review (one of my favorite sites to read and learn about the best indie lit on the scene). Read on to hear my thoughts on Elizabeth Gonzalez's short story collection-

The Universal Physics of Escape

.

P.S.- Keep an eye out for an upcoming author interview...

P.S.- Keep an eye out for an upcoming author interview...

Published on February 12, 2016 06:12

January 29, 2016

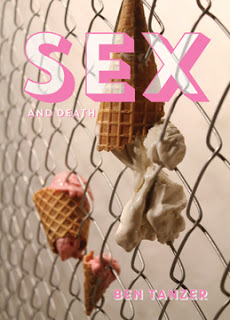

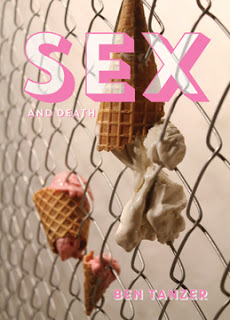

Sex and Death and Dreams: A High-Speed Interview with Ben Tanzer

Ben Tanzer has been on my radar for while now, every since I read his short story collection Lost in Space last year. I interviewed him, he interviewed me and we bonded over Darth Vader (among many other things). Tanzer is a brilliant writer, a kind and hilarious soul, and a huge advocate in the literary world, both large and small. He's the kind of guy you'd buy drinks for all night, just to keep him telling stories. I plan to do this if I ever make it out to Chicago, but in the meantime I can content myself with Tanzer's recently released collection

Sex and Death

. And this interview. Read on...

Steph Post: Okay, I'm going to go ahead and start with point of view. Most of the stories in Sex and Death (and many of your other stories) are written in 2nd person. It's a little unusual, but it absolutely works for your style. Do you find writing in 2nd person POV natural or is this a conscious decision? How do you think writing in this style changes the story-reader relationship?

Ben Tanzer: I rarely consciously start a piece in 2nd person, and I probably never shift to 2nd person when I'm editing, but the dreamier the pieces play out in my head, the more likely they are come out written that way, and ultimately stay that way, and I find that 2nd person reads, and feels, dreamier to me. And so, these pieces started dreamy as I pictured them, and they stayed that way as I edited them. They are stories that take place for the most part in the protagonists' heads and this is what they sounded like my head. As far as the reader goes then, my hope is that reader feels like I'm in their head as well, that I know how they would think and act if they were in the same position and that we are practically in real time as we experience the story - something I'm always interested in - and I think 2nd person invites all of that. SP: This collection, Sex and Death, obviously contains stories that all feature sex and, less noticeably, death. How did this collection develop? Were any of these stories written specifically for this book?

BT: They were a series of pieces that came together at the same time, not necessarily with a collection in mind - though in general, I'm always thinking in those terms - but as a reflection of a certain kind of mood I was in, seeing things as dreamier, and at a distance, possibly in reaction to the more visceral, or dialogue-driven, The New York Stories - and then as the idea of these pieces were coming together in my head and as a collection started to feel like a thing, I thought of pieces I had written at other times when I was clearly in the same kind of dreamy, distant, out of body mood, and did some retrofitting to further ensure they hung together.

SP: You never seem to shy away from the awkward- whether this be in characters, narrative style or how you make the reader feel. Why is awkwardness something that you have embraced as a storyteller?

BT: I have a lot of things I am easily embarrassed about in myself - a lack of humility for example - but awkwardly making my way through the world is not one of those things, especially in retrospect. But I have embraced it because it's such a universal feeling, common even, and in that, it's such a rich material for writing. And yet, even with my own comfort with my discomfort, these people aren't me, not totally, and not in some of their worst behavior. So I get the feeling, and I can see what it looks like, and I can feel it, but that doesn't mean it is, or was, me, and so from that perspective, I am removed from it, not unlike the characters themselves and in that way it's easier to write about. SP: My absolute favorite story in Sex and Death is "Dead or Alive." Even though the subject matter isn't exactly something that I can relate to, I think it effected me because it felt so deeply personal. Is there any truth to this story? And, for that matter, how much truth winds up in your fiction?

BT: I love that you dig it, it is the only piece that wasn't part of the dreamy mode I was in when so many of the pieces were written, and I didn't engage in any retrofitting. It just felt like a centerpiece sort of piece that captured the appropriate overarching beats and threads, but in a way more visceral sense. That is a visceral age though, and I felt such intense longing then, and was always on the make, like always, and in that way it is very personal, with some nuggets of truth. But all my fiction has at least a nugget of truth, it's how those nuggets evolve and play out and mash into each other, the fantasy and fears and confusions and the ways I allow them to breathe where they become fiction.

SP: Unless I missed something somewhere, I'm still not sure how the ice cream cones on the fence cover relate to either sex, death or the story collection. Care to explain? BT: I see it as something akin to a quashing of innocence, something sad and full of loss, and not quite real, but right there, intimate and confounding, striking and visual, like sex, and death, or at least my experience with them.

SP: You always seem to have something coming out- a collection, an article- or you're participating in literary events. You also run your own book review blog and podcast (and many other things as well). How important is it to be part of a literary community? And does all of this involvement effect your writing positively or negatively?

BT: It's important for me to be part of something, anything, and not because writing is lonely, because that is not my experience, writing is just one part, sometimes the best part, of a very full day, but that's the thing, I want a full life, doing cool shit, meeting people, especially writers, but comedians and artists and changemakers too - creating, running around, and consuming everything possible, trying to give back, support people, maybe transform lives, mine included. And so being part of the lit community provides all of that, which for me is a blessing. Now does it effect the writing positively or negatively, I don't know, but it makes me happier and feel alive, and all of that's definitely a positive. SP: And to pass along the love- what are three upcoming novel or collection releases that you're particularly excited about?

BT: So many Post, you can't believe it. Or maybe you can. Anyway, Single Stroke Seven by Lavinia Ludlow, The History of Great Things by Elizabeth Crane and The Telling by Zoe Zolbrod. So many thanks to Ben Tanzer for coming by, keeping it real and infusing all of his crazy energy into what otherwise might be a very dull and different literary scene. :) Check out

Sex and Death

,

Lost in Space

,

The New York Stories

and Tanzer's many other collections and be sure to stop by This Blog Will Change Your Life- his rockin' blog/podcast/website as well. Cheers and happy reading!

So many thanks to Ben Tanzer for coming by, keeping it real and infusing all of his crazy energy into what otherwise might be a very dull and different literary scene. :) Check out

Sex and Death

,

Lost in Space

,

The New York Stories

and Tanzer's many other collections and be sure to stop by This Blog Will Change Your Life- his rockin' blog/podcast/website as well. Cheers and happy reading!

Steph Post: Okay, I'm going to go ahead and start with point of view. Most of the stories in Sex and Death (and many of your other stories) are written in 2nd person. It's a little unusual, but it absolutely works for your style. Do you find writing in 2nd person POV natural or is this a conscious decision? How do you think writing in this style changes the story-reader relationship?

Ben Tanzer: I rarely consciously start a piece in 2nd person, and I probably never shift to 2nd person when I'm editing, but the dreamier the pieces play out in my head, the more likely they are come out written that way, and ultimately stay that way, and I find that 2nd person reads, and feels, dreamier to me. And so, these pieces started dreamy as I pictured them, and they stayed that way as I edited them. They are stories that take place for the most part in the protagonists' heads and this is what they sounded like my head. As far as the reader goes then, my hope is that reader feels like I'm in their head as well, that I know how they would think and act if they were in the same position and that we are practically in real time as we experience the story - something I'm always interested in - and I think 2nd person invites all of that. SP: This collection, Sex and Death, obviously contains stories that all feature sex and, less noticeably, death. How did this collection develop? Were any of these stories written specifically for this book?

BT: They were a series of pieces that came together at the same time, not necessarily with a collection in mind - though in general, I'm always thinking in those terms - but as a reflection of a certain kind of mood I was in, seeing things as dreamier, and at a distance, possibly in reaction to the more visceral, or dialogue-driven, The New York Stories - and then as the idea of these pieces were coming together in my head and as a collection started to feel like a thing, I thought of pieces I had written at other times when I was clearly in the same kind of dreamy, distant, out of body mood, and did some retrofitting to further ensure they hung together.

SP: You never seem to shy away from the awkward- whether this be in characters, narrative style or how you make the reader feel. Why is awkwardness something that you have embraced as a storyteller?

BT: I have a lot of things I am easily embarrassed about in myself - a lack of humility for example - but awkwardly making my way through the world is not one of those things, especially in retrospect. But I have embraced it because it's such a universal feeling, common even, and in that, it's such a rich material for writing. And yet, even with my own comfort with my discomfort, these people aren't me, not totally, and not in some of their worst behavior. So I get the feeling, and I can see what it looks like, and I can feel it, but that doesn't mean it is, or was, me, and so from that perspective, I am removed from it, not unlike the characters themselves and in that way it's easier to write about. SP: My absolute favorite story in Sex and Death is "Dead or Alive." Even though the subject matter isn't exactly something that I can relate to, I think it effected me because it felt so deeply personal. Is there any truth to this story? And, for that matter, how much truth winds up in your fiction?

BT: I love that you dig it, it is the only piece that wasn't part of the dreamy mode I was in when so many of the pieces were written, and I didn't engage in any retrofitting. It just felt like a centerpiece sort of piece that captured the appropriate overarching beats and threads, but in a way more visceral sense. That is a visceral age though, and I felt such intense longing then, and was always on the make, like always, and in that way it is very personal, with some nuggets of truth. But all my fiction has at least a nugget of truth, it's how those nuggets evolve and play out and mash into each other, the fantasy and fears and confusions and the ways I allow them to breathe where they become fiction.

SP: Unless I missed something somewhere, I'm still not sure how the ice cream cones on the fence cover relate to either sex, death or the story collection. Care to explain? BT: I see it as something akin to a quashing of innocence, something sad and full of loss, and not quite real, but right there, intimate and confounding, striking and visual, like sex, and death, or at least my experience with them.

SP: You always seem to have something coming out- a collection, an article- or you're participating in literary events. You also run your own book review blog and podcast (and many other things as well). How important is it to be part of a literary community? And does all of this involvement effect your writing positively or negatively?