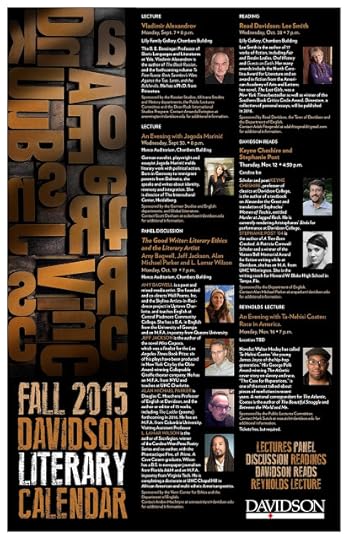

Steph Post's Blog, page 31

September 21, 2015

Summer Round Up!

Appearently summer is over this week (though you wouldn't know it here...) and as we're going into fall (or post-summer in this part of FL) I'd like to take a quick look back at the "wow" books from the past few months. Unlike last year, where I was gobbling up debuts like it was nobody's business, I've been shying away from contemporary literature lately in light of the fact that I'm deep in my hobbit hole of writing. It's that whole Anxiety of Influence thing... I've been absorbed in research and classics, but a few of today's hot up-and-coming writers managed to break their way through and conquer my heart. If you haven't bought and read these gems already... hop to it!

Brian Panowich's Bull Mountain.

"Bull Mountain has everything you would want in this genre: outlaws, grit, violence and filial loyalties being smashed together and pulled apart, all with a literary grace that is both natural and surprising."

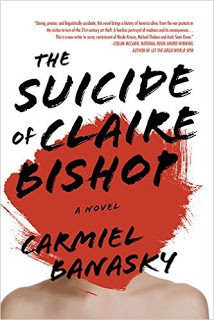

The Suicide of Claire Bishop by Carmiel Banasky

"I’ll just go ahead and say it now- Carmiel Banasky’s physiological tour de force The Suicide of Claire Bishop is going to be one of THOSE books. You know, one of the novels that everyone is talking about this fall."

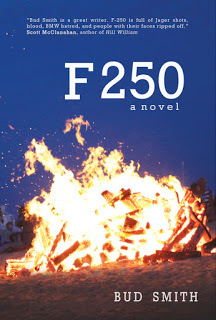

Bud Smith's F 250

"Many a novel has tried to walk the line Smith takes here and the story ends only in hipster posturing and pretention. Without a doubt, Bud Smith’s F 250 is the real deal."

Then there's also the books that I was lucky enough to obtain an advance copy of. Be on the lookout for these beauties in the coming months....

Fallen Land by Taylor Brown- January, 2016

Eric Shonkwiler's Moon Up, Past Full- October, 2015

God in Neon by Sam Slaughter- Winter, 2015

And then there's a few other books that dazzled me this summer- just in case you were interested...

A Constellation of Vital Phenomena by Anthony Marra

Brideshead Revisited by Evelyn Waugh

Brideshead Revisited by Evelyn Waugh

Simon Mawer's The Glass Room

Happy Reading!!!

Brian Panowich's Bull Mountain.

"Bull Mountain has everything you would want in this genre: outlaws, grit, violence and filial loyalties being smashed together and pulled apart, all with a literary grace that is both natural and surprising."

The Suicide of Claire Bishop by Carmiel Banasky

"I’ll just go ahead and say it now- Carmiel Banasky’s physiological tour de force The Suicide of Claire Bishop is going to be one of THOSE books. You know, one of the novels that everyone is talking about this fall."

Bud Smith's F 250

"Many a novel has tried to walk the line Smith takes here and the story ends only in hipster posturing and pretention. Without a doubt, Bud Smith’s F 250 is the real deal."

Then there's also the books that I was lucky enough to obtain an advance copy of. Be on the lookout for these beauties in the coming months....

Fallen Land by Taylor Brown- January, 2016

Eric Shonkwiler's Moon Up, Past Full- October, 2015

God in Neon by Sam Slaughter- Winter, 2015

And then there's a few other books that dazzled me this summer- just in case you were interested...

A Constellation of Vital Phenomena by Anthony Marra

Brideshead Revisited by Evelyn Waugh

Brideshead Revisited by Evelyn Waugh

Simon Mawer's The Glass Room

Happy Reading!!!

Published on September 21, 2015 15:10

September 18, 2015

What Are You Reading?

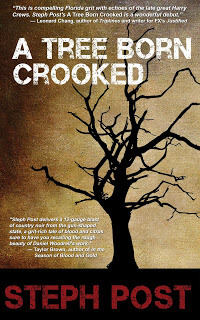

Many thanks to Maureen O'Leary Wanket for her review of A Tree Born Crooked on her "What Are You Reading?" round-up. This is great review list to check out if you're looking for some killer books, by the way....

Published on September 18, 2015 13:57

September 17, 2015

5+20 Female Short Story Writers

Thrilled to be included on this list: 5+20 Female Short Story Writers You Should Be Reading Right Now by Entropy Magazine. And even better- this list includes story excerpts from all of the mentioned authors so you can get to know their work and why they were included on this list. My "authors-to-read" list had already grown tremendously and I'm sure yours will too. Have a read...

Published on September 17, 2015 13:31

September 14, 2015

The Art of Madness: An Interview with Carmiel Banasky, author of The Suicide of Claire Bishop

I’ll just go ahead and say it now- Carmiel Banasky’s physiological tour de force The Suicide of Claire Bishop is going to be one of THOSE books. You know, one of the novels that everyone is talking about this fall. Complete with schizophrenic characters, art theft, Greenwich Village in the 60s, paranoia, Hasidism and the possibility of time travel, The Suicide of Claire Bishop is a whirlwind of a complex and utterly brilliant story. I’ve already recommended it over on Writer’s Bone and now I’m thrilled to bring you an interview with the author. I dove deep with Banasky and she chose to dive even deeper. This is an interview for readers, yes, but especially for writers. The Suicide of Claire Bishop debuts tomorrow (September 15th) so read on and be sure to pick up your copy this week.

Steph Post: The Suicide of Claire Bishop is written from two different character’s viewpoints, with different point of view styles. The narrative jumps back and forth between Claire Bishop in 1959 and West Butler (in first person) in 2004. While they are are linked by the portrait of Claire, every other aspect of their stories is very different, from events to voice to time period to gender. Even the fact that Claire is sane and West is schizophrenic. I’m curious about the process of crafting one novel containing two very different narratives. Did you write the novel straight through, alternating between characters as you went along, or did you write first one story and then the other? And how did you keep the dual stories focused and on track for the ultimate meeting of Claire and West?

Carmiel Banasky: I wrote a lot of my novel straight through, alternating their voices. (Though in my first drafts, I started with West before shifting back in time to Claire.) But big plot pieces came to me later, only after I could see what Claire and West’s character arcs were from a more aerial view. There were missing periods of growth and change or despair that I could only write having seen how both narratives parallel or move away from one another. I think much of the sixties sections I wrote later. And once I had one of them visiting their hometown and staying with their mother, I knew the other character had to as well. In many ways, their narratives are similar to me, or they reflect one another in an old, marred mirror sort of way: while one steals the painting and the other has the painting stolen, they both struggle with family, identity, pressures from society. They are both forced to question the fragility and control one has over one’s own mind and self, and how a diagnosis can define a life, or not.

From the outset, I knew that West was going to aid Claire in achieving the thing she’d been pondering all her life (maybe it’s obvious but I’m avoiding using a spoiler key-word here!). I knew the purpose of their meeting from the beginning stages of drafting. But, even though I knew what point A and point B were, I didn’t know what route I would take between them. I excised a lot that seemed OUT of focus on the track to get West and Claire where they had to be in the end. For West, his timeframe is shorter and his plot follows more of a mystery structure: finding and deciphering clues, even if they are only in his head. I felt like I had to focus his attention by allowing him to interpret everything he comes across as a clue connected to the painting or the painter, Nicolette. With Claire, anything could happen as we follow her over many decades. I had to choose the highlights that both disrupt and guide her character arc. Maybe the questions I posed were: What unsettled her from herself? What moments got her out of the comfort zone of the stories she was telling about herself? I’d like to think everything that made it into the book is vital in telling the story of how West and Claire become who they become to one another.

SP: Aside from the obvious fact of two stories and two characters dominating The Suicide of Claire Bishop, the themes of opposites and dualities are reflected throughout both the narrative and the style. There are the obvious character traits- male and female, sane and insane, 1950s and 2000s- but I was most interested in how your language conveyed this same sense of duplicity. Line such as “There Claire was, and wasn’t.” and “I am a lie. But I am not a liar.” Was this an intentional style decision, to mirror the schizophrenia of West and the uncertainty of Claire, or did the language come naturally to the story?

CB: I think the answer is two-fold: 1) These lines are probably instances of where my voice meets or overlaps with my characters’ voices. A “natural” language, like you said. And 2) I wanted to create moments, through language and through thought processes, to show how similar Claire and West really are. In Claire, I set out to portray a character who was sane, but who had been close to madness, or the idea of it, all her life. Claire is as obsessed with madness as she is fearful of it. When their voices overlap stylistically, it is Claire sinking further into her own brand of madness, or West lifting out of his. Our brains are so fragile, and West is not so different from the rest of us. He just makes a lot of hairpin turns while the rest of us stick to what seems to be a straighter path. That may be a horrible metaphor. But in any case, both paths follow a certain logic. I wanted West to feel relatable. One way to achieve that was to align the styles I used for both characters. Claire’s sanity is not so far removed from West’s insanity. The line between the two is thin.

SP: While there is, of course, a tradition of madness in literature, I was struck by how Claire is defined by her sanity. The artist Nicolette, after depicting Claire’s suicide in her portrait, comments, “You lived your life afraid you’d go mad… And now you’re disappointed.” It is this disappointment, and the seemingly infinite stretch of life looming ahead of her once she realizes that she does not have hereditary madness, that marks Claire’s character. What prompted you to write about un-insanity (for lack of a better word)?

CB: A good friend had a similar experience and shared it with me. I was already beginning to write both of these characters, and I was a sponge at that point in the writing process. I grasped onto that story when I heard it and immediately asked my friend, a poet, for permission to use it in my novel. She granted it, and was one of my first readers. It was exactly, thematically and plot-wise, what I had been waiting for. (I love that time in the writing process. Was it Saul Bellow who said something about having his suction cups at the ready?) In retrospect, maybe I was looking for a backstory that linked Claire and West through a difference. Claire thought her trajectory would look like West’s. She is so convinced and attached to this narrative of going mad, of unknowing herself by losing her mind, that when she learns that that the narrative is actually something other, she does in fact lose track of who she is. She no longer knows herself. The unknowing and redefining still occur.

SP: You write the character of West Butler extremely convincingly and I appreciated how well you portrayed his schizophrenia. What was the research process like for you to be able to so fully craft his character?

CB: I suppose I did a lot of asking permission in order to write this book. I had two friends who were diagnosed with schizophrenia and who had very similar experiences. They told me about their episodes. I was struck by the similarity. I was struck also by my own reaction, which was partly of fear—how my extraordinarily functional, brilliant friends could suddenly have brains so suddenly (it seemed to me) out of their own control. And finally, I was struck by the fact that I was so struck: I hadn’t read experiences like these in literature before, especially not in the first person. I wanted to write characters they could recognize (though West is completely different from both of them in most other ways). More importantly, I wanted to write a character with schizophrenia who is as relatable, loveable, and familiar as any character without schizophrenia to any reader who has or has not had experience with mental illness. I wanted to portray a whole human, schizophrenia being one of many characteristics.

I interviewed others with different types of mental illnesses about their journeys in and out of recovery. I read memoirs, novels, and some clinical books. I read essays geared toward family members of those with schizophrenia. I had a therapist friend read a draft. Elyn Saks’s writing and talks were a huge help. But the research could have been endless. At some point, I had to stop. I’m sure I didn’t read enough. There’s no way I got the experience exactly right. But I love West, that important author-character love, and I wouldn’t change him now.

There was always the question of what to put the most weight on: the story, or the portrayal of West’s disease. Luckily, these overlapped most of the time, were one and the same.

SP: Much of The Suicide of Claire Bishop is based on the concept of complicated perception, but my favorite parts of the novel are the moments of brilliant clarity where you use simple language to convey extremely difficult emotions. My favorite line comes from West as he is describing his feelings for Nicolette. He tells the reader, “I loved her so much I could rip out my collarbone.” This line floored me. Not because of its violence or its strangely poetic imagery, but because of its truth. Haven’t we all loved someone and/or been heartbroken to the point where we felt it physically, down to our bones? It’s such a simple description, but so perfect in its ability to encapsulate an otherwise slippery emotion. I have to ask then, do you have a background in poetry? Or does all of your fiction so succinctly use language to such a powerful degree?

CB: This is the type of language I learned from my friend—it’s one take on the schizophrenic linguistic style, if you will: seemingly unrelated elements coming together to create a logic that is beyond logic, that reaches a higher emotional truth. I wanted West’s language to make emotional sense even if it doesn’t make any other kind of sense. I was, however, afraid of exploiting the disease in that way, by romanticizing elements of it because some aspects felt like writerly, poetic, stylistic gifts. Lines like that are my attempt to portray the workings of West’s mind through my own literary voice.

I only write poems in secret. (Except I do have a weird historical novella in the works—fragmented poetry and prose. So some of it will hopefully see the light of day in the near future.) In general, sound and rhythm have always been the most important aspects of prose to me. But I used to, perhaps I still do sometimes but more rarely now, forsake clarity for lushness. West’s voice was a very difficult test and a great lesson: how do I allow his madness to feel logical and lyrical at once? He has his own logic, which should come across as sensical, if you are close enough to his perspective. There was also the challenge of using as few similes as possible. Something is not “like” something else to someone with schizophrenia. Things meld and overlap and many dots are connected, but simile is not commonly used. I, myself, am prone to using similes. So in one of my last revisions, I went through and excised as many instances of the word “like” (which were instances of me the author) as I could. It was a question of where my voice meets or should be reigned in from West’s voice.

SP: It is the bizarre portrait depicting Claire’s suicide that ties the characters and narratives of Claire and West together. The painting is described as “Claire at every moment of her life” as she falls from a bridge. In my mind, I saw this portrait in the style perhaps of Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase. In the novel, the portrait of Claire is painted in 1959. In your mind, who in that time period would have actually painted Claire’s suicide? Are there any contemporary artists that you think would be candidates to paint this piece?

CB: I have always seen Claire’s portrait (but never wanted to explicitly state this in the novel because I prefer that you had your own interpretation) in the style of Frida Kahlo, as I arrived at the germ of Claire’s narrative from an anecdote about the painter. Kahlo was commissioned by a Manhattan socialite to paint a portrait commemorating Dorothy Hale, the socialite’s friend who had committed suicide. Instead of a portrait, Frida depicted Hale’s death—her jump and fall from a tall building. It was considered an insult at first, but the painting, The Suicide of Dorothy Hale, is stunning on many levels. It’s dream-like; it raises so many questions about death and suicide, and about the identity of the falling woman. I didn’t realize until later that what became of Kahlo’s painting is similar to the journey the painting in my novel takes: nearly destroyed, locked away, donated anonymously, etc. The lost and found nature of both my fictional painting and Kahlo’s painting makes a lot of sense to me.

SP: The Suicide of Claire Bishop debuts on September 15 and as I’ve said, I have a strong feeling that it’s going to be one of the heavy hitters on the fall literary scene. Aside from your own, of course, are there any novels debuting this fall or winter that you’re excited about? Any books or authors I should be keeping an eye out for?

CB: So many of my friends have books out this year! It has been fantastic to celebrate with them. Here are a few: Matthew Selasses, Alexandra Kleeman, Amy Jo Burns (paperback just came out), you know Scott Cheshire of course (paperback out now), Christopher Robinson/Gavin Kovite, Steve Totlz (his second book comes out next week). Next year keep an eye out for Michael Copperman and Kaitlyn Greenidge. I’ll probably think of more another day. These are my friends, I freely admit, and also some of the best writers I’ve ever read.

Steph Post: The Suicide of Claire Bishop is written from two different character’s viewpoints, with different point of view styles. The narrative jumps back and forth between Claire Bishop in 1959 and West Butler (in first person) in 2004. While they are are linked by the portrait of Claire, every other aspect of their stories is very different, from events to voice to time period to gender. Even the fact that Claire is sane and West is schizophrenic. I’m curious about the process of crafting one novel containing two very different narratives. Did you write the novel straight through, alternating between characters as you went along, or did you write first one story and then the other? And how did you keep the dual stories focused and on track for the ultimate meeting of Claire and West?

Carmiel Banasky: I wrote a lot of my novel straight through, alternating their voices. (Though in my first drafts, I started with West before shifting back in time to Claire.) But big plot pieces came to me later, only after I could see what Claire and West’s character arcs were from a more aerial view. There were missing periods of growth and change or despair that I could only write having seen how both narratives parallel or move away from one another. I think much of the sixties sections I wrote later. And once I had one of them visiting their hometown and staying with their mother, I knew the other character had to as well. In many ways, their narratives are similar to me, or they reflect one another in an old, marred mirror sort of way: while one steals the painting and the other has the painting stolen, they both struggle with family, identity, pressures from society. They are both forced to question the fragility and control one has over one’s own mind and self, and how a diagnosis can define a life, or not.

From the outset, I knew that West was going to aid Claire in achieving the thing she’d been pondering all her life (maybe it’s obvious but I’m avoiding using a spoiler key-word here!). I knew the purpose of their meeting from the beginning stages of drafting. But, even though I knew what point A and point B were, I didn’t know what route I would take between them. I excised a lot that seemed OUT of focus on the track to get West and Claire where they had to be in the end. For West, his timeframe is shorter and his plot follows more of a mystery structure: finding and deciphering clues, even if they are only in his head. I felt like I had to focus his attention by allowing him to interpret everything he comes across as a clue connected to the painting or the painter, Nicolette. With Claire, anything could happen as we follow her over many decades. I had to choose the highlights that both disrupt and guide her character arc. Maybe the questions I posed were: What unsettled her from herself? What moments got her out of the comfort zone of the stories she was telling about herself? I’d like to think everything that made it into the book is vital in telling the story of how West and Claire become who they become to one another.

SP: Aside from the obvious fact of two stories and two characters dominating The Suicide of Claire Bishop, the themes of opposites and dualities are reflected throughout both the narrative and the style. There are the obvious character traits- male and female, sane and insane, 1950s and 2000s- but I was most interested in how your language conveyed this same sense of duplicity. Line such as “There Claire was, and wasn’t.” and “I am a lie. But I am not a liar.” Was this an intentional style decision, to mirror the schizophrenia of West and the uncertainty of Claire, or did the language come naturally to the story?

CB: I think the answer is two-fold: 1) These lines are probably instances of where my voice meets or overlaps with my characters’ voices. A “natural” language, like you said. And 2) I wanted to create moments, through language and through thought processes, to show how similar Claire and West really are. In Claire, I set out to portray a character who was sane, but who had been close to madness, or the idea of it, all her life. Claire is as obsessed with madness as she is fearful of it. When their voices overlap stylistically, it is Claire sinking further into her own brand of madness, or West lifting out of his. Our brains are so fragile, and West is not so different from the rest of us. He just makes a lot of hairpin turns while the rest of us stick to what seems to be a straighter path. That may be a horrible metaphor. But in any case, both paths follow a certain logic. I wanted West to feel relatable. One way to achieve that was to align the styles I used for both characters. Claire’s sanity is not so far removed from West’s insanity. The line between the two is thin.

SP: While there is, of course, a tradition of madness in literature, I was struck by how Claire is defined by her sanity. The artist Nicolette, after depicting Claire’s suicide in her portrait, comments, “You lived your life afraid you’d go mad… And now you’re disappointed.” It is this disappointment, and the seemingly infinite stretch of life looming ahead of her once she realizes that she does not have hereditary madness, that marks Claire’s character. What prompted you to write about un-insanity (for lack of a better word)?

CB: A good friend had a similar experience and shared it with me. I was already beginning to write both of these characters, and I was a sponge at that point in the writing process. I grasped onto that story when I heard it and immediately asked my friend, a poet, for permission to use it in my novel. She granted it, and was one of my first readers. It was exactly, thematically and plot-wise, what I had been waiting for. (I love that time in the writing process. Was it Saul Bellow who said something about having his suction cups at the ready?) In retrospect, maybe I was looking for a backstory that linked Claire and West through a difference. Claire thought her trajectory would look like West’s. She is so convinced and attached to this narrative of going mad, of unknowing herself by losing her mind, that when she learns that that the narrative is actually something other, she does in fact lose track of who she is. She no longer knows herself. The unknowing and redefining still occur.

SP: You write the character of West Butler extremely convincingly and I appreciated how well you portrayed his schizophrenia. What was the research process like for you to be able to so fully craft his character?

CB: I suppose I did a lot of asking permission in order to write this book. I had two friends who were diagnosed with schizophrenia and who had very similar experiences. They told me about their episodes. I was struck by the similarity. I was struck also by my own reaction, which was partly of fear—how my extraordinarily functional, brilliant friends could suddenly have brains so suddenly (it seemed to me) out of their own control. And finally, I was struck by the fact that I was so struck: I hadn’t read experiences like these in literature before, especially not in the first person. I wanted to write characters they could recognize (though West is completely different from both of them in most other ways). More importantly, I wanted to write a character with schizophrenia who is as relatable, loveable, and familiar as any character without schizophrenia to any reader who has or has not had experience with mental illness. I wanted to portray a whole human, schizophrenia being one of many characteristics.

I interviewed others with different types of mental illnesses about their journeys in and out of recovery. I read memoirs, novels, and some clinical books. I read essays geared toward family members of those with schizophrenia. I had a therapist friend read a draft. Elyn Saks’s writing and talks were a huge help. But the research could have been endless. At some point, I had to stop. I’m sure I didn’t read enough. There’s no way I got the experience exactly right. But I love West, that important author-character love, and I wouldn’t change him now.

There was always the question of what to put the most weight on: the story, or the portrayal of West’s disease. Luckily, these overlapped most of the time, were one and the same.

SP: Much of The Suicide of Claire Bishop is based on the concept of complicated perception, but my favorite parts of the novel are the moments of brilliant clarity where you use simple language to convey extremely difficult emotions. My favorite line comes from West as he is describing his feelings for Nicolette. He tells the reader, “I loved her so much I could rip out my collarbone.” This line floored me. Not because of its violence or its strangely poetic imagery, but because of its truth. Haven’t we all loved someone and/or been heartbroken to the point where we felt it physically, down to our bones? It’s such a simple description, but so perfect in its ability to encapsulate an otherwise slippery emotion. I have to ask then, do you have a background in poetry? Or does all of your fiction so succinctly use language to such a powerful degree?

CB: This is the type of language I learned from my friend—it’s one take on the schizophrenic linguistic style, if you will: seemingly unrelated elements coming together to create a logic that is beyond logic, that reaches a higher emotional truth. I wanted West’s language to make emotional sense even if it doesn’t make any other kind of sense. I was, however, afraid of exploiting the disease in that way, by romanticizing elements of it because some aspects felt like writerly, poetic, stylistic gifts. Lines like that are my attempt to portray the workings of West’s mind through my own literary voice.

I only write poems in secret. (Except I do have a weird historical novella in the works—fragmented poetry and prose. So some of it will hopefully see the light of day in the near future.) In general, sound and rhythm have always been the most important aspects of prose to me. But I used to, perhaps I still do sometimes but more rarely now, forsake clarity for lushness. West’s voice was a very difficult test and a great lesson: how do I allow his madness to feel logical and lyrical at once? He has his own logic, which should come across as sensical, if you are close enough to his perspective. There was also the challenge of using as few similes as possible. Something is not “like” something else to someone with schizophrenia. Things meld and overlap and many dots are connected, but simile is not commonly used. I, myself, am prone to using similes. So in one of my last revisions, I went through and excised as many instances of the word “like” (which were instances of me the author) as I could. It was a question of where my voice meets or should be reigned in from West’s voice.

SP: It is the bizarre portrait depicting Claire’s suicide that ties the characters and narratives of Claire and West together. The painting is described as “Claire at every moment of her life” as she falls from a bridge. In my mind, I saw this portrait in the style perhaps of Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase. In the novel, the portrait of Claire is painted in 1959. In your mind, who in that time period would have actually painted Claire’s suicide? Are there any contemporary artists that you think would be candidates to paint this piece?

CB: I have always seen Claire’s portrait (but never wanted to explicitly state this in the novel because I prefer that you had your own interpretation) in the style of Frida Kahlo, as I arrived at the germ of Claire’s narrative from an anecdote about the painter. Kahlo was commissioned by a Manhattan socialite to paint a portrait commemorating Dorothy Hale, the socialite’s friend who had committed suicide. Instead of a portrait, Frida depicted Hale’s death—her jump and fall from a tall building. It was considered an insult at first, but the painting, The Suicide of Dorothy Hale, is stunning on many levels. It’s dream-like; it raises so many questions about death and suicide, and about the identity of the falling woman. I didn’t realize until later that what became of Kahlo’s painting is similar to the journey the painting in my novel takes: nearly destroyed, locked away, donated anonymously, etc. The lost and found nature of both my fictional painting and Kahlo’s painting makes a lot of sense to me.

SP: The Suicide of Claire Bishop debuts on September 15 and as I’ve said, I have a strong feeling that it’s going to be one of the heavy hitters on the fall literary scene. Aside from your own, of course, are there any novels debuting this fall or winter that you’re excited about? Any books or authors I should be keeping an eye out for?

CB: So many of my friends have books out this year! It has been fantastic to celebrate with them. Here are a few: Matthew Selasses, Alexandra Kleeman, Amy Jo Burns (paperback just came out), you know Scott Cheshire of course (paperback out now), Christopher Robinson/Gavin Kovite, Steve Totlz (his second book comes out next week). Next year keep an eye out for Michael Copperman and Kaitlyn Greenidge. I’ll probably think of more another day. These are my friends, I freely admit, and also some of the best writers I’ve ever read.

Published on September 14, 2015 13:02

September 10, 2015

A Tree Born Crooked on WGCU

So this is pretty awesome- A Tree Born Crooked was reviewed by Sally Bissell on WGCU (Southwest Florida's NPR station). Many, many thanks!

Published on September 10, 2015 10:53

September 9, 2015

A Conversation with Steph Post- The Spark

Many thanks to Kevin Catalano for this killer interview up at Alternating Current's The Spark. This was by far one of my favorite interviews, as Kevin conjured up questions about everything from tattoos to badass women to, of course,

A Tree Born Crooked

. Read on!

Published on September 09, 2015 10:23

August 31, 2015

Shaping Memories: A Conversation with Will Boast, Author of Epilogue: A Memoir

Today's interview was a long time coming and, as I'm sure you'll agree, worth every moment of the wait. I read Will Boast's

Epilogue: A Memoir

last fall and challenged him with some hard-hitting questions. As Epilogue will be released in paperback this week, it's a perfect time to dive back into Boast's story of love, loss, memory, grief and, most essential to the novel, the mysteries and complicated bonds of family. Read on as Boast and I discuss authenticity, writing painful scenes and the complex line between truth and fiction, novel and memoir.

Steph Post: As a fiction writer, I am both fascinated and terrified by the idea of writing a memoir. When I took a memoir writing class in grad school one of the most difficult parts for me was staying true to the facts and not embellishing or derailing events to create a better story. I’m curious how you handled this balance. Were you ever tempted to stretch the truth for the sake of the book? While writing, did you ever struggle with crafting a scene for readers, knowing that you had to both entertain and be authentic?

Will Boast: I hear what you’re saying and absolutely agree. There are some skills that cross over from writing fiction to writing explicit autobiography, but just as many that do not. I actually started Epilogue as a novel, and it took me at least a couple years to realize that, for various reasons, it had to be nonfiction. That was a long process with a lot of hesitations and strange turns into odd hybrids of the two genres. Once I settled on something like memoir (I still consider Epilogue something of a hybrid), I really began to grapple with the subject and the memories. Instead of shaping the material, I had to find its shape, if that makes any sense. I had to think about it all more deeply and more analytically, and to be honest I learned a great deal about my family by moving away from fiction (not that trying it as a novel didn’t help also). Strangely, I found that playing down the dread and joy and confusion of actual experiences tended to make them more powerfully felt on the page. So, no, I wasn’t tempted to punch anything up. A certain reticence became a big part of the book.

SP: Epilogue is a story of discovery through death and while it is not all bleak, there are many parts in the novel that felt like I was being punched in the stomach while reading. The Prologue was particularly painful (which, I suppose, it should be, since it is titled “Pain”) and much of the description of your mother dying was difficult to get through. A scene that I found extremely gut-wrenching was in the chapter “Strangers.” When you relate how your mother no longer recognized you at the dinner table, it seems as if the story has hit rock bottom. If I was upset reading this scene, I can only imagine how you must have felt in writing it. How did you handle writing about the terror, grief, depression and other dark emotions you felt at the time? Do you think such powerful emotions hindered or helped the writing process?

WB: It wasn’t just a process of writing scenes like the one you mentioned but re-writing and re-working and revisiting them again and again and again. I hope this doesn’t sound too grim, but I would not recommend this sort of thing to many people. I don’t know if it hindered or helped the drafting of the book. Everything takes me a very long time to write, in part because I’m an inveterate, obsessive tinkerer. I don’t think this is the best way to proceed, not at all, but I don’t seem to have much choice in the matter. I would say that it’s been a bit of a relief to get back to fiction, especially the novel I’m working on now, because I feel that I have a little more room to play around.

SP: My favorite chapter in Epilogue is “Overdue.” Even though it still connects heavily to your mother and her escalating illness, it was somewhat of a much needed reprieve. It was clever to break the chapter up by book genres and the Dewey Decimal system, but it was also extremely revealing. I felt like there was more honesty in this chapter than almost anywhere else in the book. Perhaps because it mostly contained childhood memories, but also because I think the library scenes created a strong connection with the reader. Most readers and writers haunted libraries as they grew up. Your descriptions of such simple things as the sound of books sliding into a book drop brought back a host of memories for me. (That, and your mention of the Dragonriders of Pern series…) Why did you make such a point of going into detail with the library scenes?

WB: Thank you and glad you enjoyed it! Strangely, “Overdue” is the one chapter I considered taking out of the draft. I put it in and took it out several times, and then re-wrote it at the last minute—literally on my editor’s desk, with a blue pencil and eraser crumbs piling up everywhere. I almost had a nervous breakdown. Now that I think of it, this was on 5th Ave, right across from the New York Public Library…. I had a nice time excavating the details and the tiny little sensations of my own little public library, and I came to agree with others who found the chapter a moment of quiet in the general doom and destruction, though the chapter is, in a way, a eulogy. I think dwelling with those little details became necessary, because it is, dramatically speaking, a quieter sequence in the book. I’m glad I left it in, but I definitely sweated a lot over it.

SP: The true gravity of Epilogue hit me in the last chapter. Aptly titled “Revision,” this chapter goes back over the story of your mother and father meeting, the secret marriages both had before, and the death of your father. Periodically throughout the chapter sentences are crossed out to further cement the idea of revision. This made me think about the nature of memory itself and how complicated it is. How can you ever be sure that you are remembering something correctly? Does it even matter if it’s correct if you remember it a certain way? I imagined as I was reading that these were concepts you had to consider while writing. Did the idea of memory itself ever preoccupy you while writing?

WB: I did the best I could to remember it all accurately, but you’re right—there is an inherent uncertainty in the genre: Did it happen exactly like that? You’d think that going to other sources, talking to, even interviewing others who might have been there or knew the people involved, might help with this. But, in my experience anyway, if you talk to five different people, you’ll get five different versions of what happened. We’re simply too bound up with our allegiances and our own fragile identities not to slant the actual experience in some way. So, yes, I did have many occasions to ruminate on the fallibility of memory. Most of that thinking, however, got cut out of the manuscript. I think you end up understanding that a certain degree of questioning and re-evaluating memory is a part of the genre of memoir—the proof is in the name itself--but it would perhaps be paralyzing, for reader and writer both, to lean too heavily on this. Also, I think it’s important to remember that memoir is not simply remembering. (If it were, it would be rather easier to write.) To paraphrase, Lucy Grealy, whose Autobiography of a Face I like a lot, you don’t remember a memoir, you write it. At first I thought this was a bit of a dodge on the question you’re asking. But now I think I agree. The best of the genre is every bit as artfully made as the best novels. If fiction is the art of invention, memoir is the art of selection and arrangement (and interrogation of experience and the careful balancing of tone and effect). It’s not just a transcript of actual life, in other words, but a re-enactment, a summoning, of it.

SP: Finally, I have to wonder, where do you go from here? You were a published short story writer before Epilogue hit the scene. Are you planning on returning to fiction? Do you think that possibly you will ever write about your own life again?

WB: Yes, back to fiction. I’m finishing a novel. As for explicit autobiography, perhaps. I always think I can plan 2-5 years into the future, and I always find out that I’m wrong.

Many thanks to Will Boast for stopping by. Be sure to pick up your copy of

Epilogue: A Memoir today!

Many thanks to Will Boast for stopping by. Be sure to pick up your copy of

Epilogue: A Memoir today!

Steph Post: As a fiction writer, I am both fascinated and terrified by the idea of writing a memoir. When I took a memoir writing class in grad school one of the most difficult parts for me was staying true to the facts and not embellishing or derailing events to create a better story. I’m curious how you handled this balance. Were you ever tempted to stretch the truth for the sake of the book? While writing, did you ever struggle with crafting a scene for readers, knowing that you had to both entertain and be authentic?

Will Boast: I hear what you’re saying and absolutely agree. There are some skills that cross over from writing fiction to writing explicit autobiography, but just as many that do not. I actually started Epilogue as a novel, and it took me at least a couple years to realize that, for various reasons, it had to be nonfiction. That was a long process with a lot of hesitations and strange turns into odd hybrids of the two genres. Once I settled on something like memoir (I still consider Epilogue something of a hybrid), I really began to grapple with the subject and the memories. Instead of shaping the material, I had to find its shape, if that makes any sense. I had to think about it all more deeply and more analytically, and to be honest I learned a great deal about my family by moving away from fiction (not that trying it as a novel didn’t help also). Strangely, I found that playing down the dread and joy and confusion of actual experiences tended to make them more powerfully felt on the page. So, no, I wasn’t tempted to punch anything up. A certain reticence became a big part of the book.

SP: Epilogue is a story of discovery through death and while it is not all bleak, there are many parts in the novel that felt like I was being punched in the stomach while reading. The Prologue was particularly painful (which, I suppose, it should be, since it is titled “Pain”) and much of the description of your mother dying was difficult to get through. A scene that I found extremely gut-wrenching was in the chapter “Strangers.” When you relate how your mother no longer recognized you at the dinner table, it seems as if the story has hit rock bottom. If I was upset reading this scene, I can only imagine how you must have felt in writing it. How did you handle writing about the terror, grief, depression and other dark emotions you felt at the time? Do you think such powerful emotions hindered or helped the writing process?

WB: It wasn’t just a process of writing scenes like the one you mentioned but re-writing and re-working and revisiting them again and again and again. I hope this doesn’t sound too grim, but I would not recommend this sort of thing to many people. I don’t know if it hindered or helped the drafting of the book. Everything takes me a very long time to write, in part because I’m an inveterate, obsessive tinkerer. I don’t think this is the best way to proceed, not at all, but I don’t seem to have much choice in the matter. I would say that it’s been a bit of a relief to get back to fiction, especially the novel I’m working on now, because I feel that I have a little more room to play around.

SP: My favorite chapter in Epilogue is “Overdue.” Even though it still connects heavily to your mother and her escalating illness, it was somewhat of a much needed reprieve. It was clever to break the chapter up by book genres and the Dewey Decimal system, but it was also extremely revealing. I felt like there was more honesty in this chapter than almost anywhere else in the book. Perhaps because it mostly contained childhood memories, but also because I think the library scenes created a strong connection with the reader. Most readers and writers haunted libraries as they grew up. Your descriptions of such simple things as the sound of books sliding into a book drop brought back a host of memories for me. (That, and your mention of the Dragonriders of Pern series…) Why did you make such a point of going into detail with the library scenes?

WB: Thank you and glad you enjoyed it! Strangely, “Overdue” is the one chapter I considered taking out of the draft. I put it in and took it out several times, and then re-wrote it at the last minute—literally on my editor’s desk, with a blue pencil and eraser crumbs piling up everywhere. I almost had a nervous breakdown. Now that I think of it, this was on 5th Ave, right across from the New York Public Library…. I had a nice time excavating the details and the tiny little sensations of my own little public library, and I came to agree with others who found the chapter a moment of quiet in the general doom and destruction, though the chapter is, in a way, a eulogy. I think dwelling with those little details became necessary, because it is, dramatically speaking, a quieter sequence in the book. I’m glad I left it in, but I definitely sweated a lot over it.

SP: The true gravity of Epilogue hit me in the last chapter. Aptly titled “Revision,” this chapter goes back over the story of your mother and father meeting, the secret marriages both had before, and the death of your father. Periodically throughout the chapter sentences are crossed out to further cement the idea of revision. This made me think about the nature of memory itself and how complicated it is. How can you ever be sure that you are remembering something correctly? Does it even matter if it’s correct if you remember it a certain way? I imagined as I was reading that these were concepts you had to consider while writing. Did the idea of memory itself ever preoccupy you while writing?

WB: I did the best I could to remember it all accurately, but you’re right—there is an inherent uncertainty in the genre: Did it happen exactly like that? You’d think that going to other sources, talking to, even interviewing others who might have been there or knew the people involved, might help with this. But, in my experience anyway, if you talk to five different people, you’ll get five different versions of what happened. We’re simply too bound up with our allegiances and our own fragile identities not to slant the actual experience in some way. So, yes, I did have many occasions to ruminate on the fallibility of memory. Most of that thinking, however, got cut out of the manuscript. I think you end up understanding that a certain degree of questioning and re-evaluating memory is a part of the genre of memoir—the proof is in the name itself--but it would perhaps be paralyzing, for reader and writer both, to lean too heavily on this. Also, I think it’s important to remember that memoir is not simply remembering. (If it were, it would be rather easier to write.) To paraphrase, Lucy Grealy, whose Autobiography of a Face I like a lot, you don’t remember a memoir, you write it. At first I thought this was a bit of a dodge on the question you’re asking. But now I think I agree. The best of the genre is every bit as artfully made as the best novels. If fiction is the art of invention, memoir is the art of selection and arrangement (and interrogation of experience and the careful balancing of tone and effect). It’s not just a transcript of actual life, in other words, but a re-enactment, a summoning, of it.

SP: Finally, I have to wonder, where do you go from here? You were a published short story writer before Epilogue hit the scene. Are you planning on returning to fiction? Do you think that possibly you will ever write about your own life again?

WB: Yes, back to fiction. I’m finishing a novel. As for explicit autobiography, perhaps. I always think I can plan 2-5 years into the future, and I always find out that I’m wrong.

Many thanks to Will Boast for stopping by. Be sure to pick up your copy of

Epilogue: A Memoir today!

Many thanks to Will Boast for stopping by. Be sure to pick up your copy of

Epilogue: A Memoir today!

Published on August 31, 2015 12:58

August 29, 2015

Reading at Davidson College in November

Published on August 29, 2015 15:08

August 28, 2015

Catching Up with Jeff Messick: Author of Knights of the Shield

Today, I'm talking with Jeff Messick, whose novel

Knights of the Shield

just debuted in July. Read on to find out more about Jeff, his genre-bending book and the many projects he's working on now.

Steph Post: Knights of the Shield is your debut novel and has only been out since July. Now that the book is out, how do you feel? Excited? Relieved? Ready for the next one?

Jeff Messick: A combination of everything, really. I'm really excited to finally be published; it's been a lifelong dream since I was around fifteen. Relieved that I have crossed the finish line and actually completed a project. I am already at work on five more projects, one of which will feature characters from Knights of the Shield in recurring roles for an ongoing series.

SP: Your novel focuses on the characters of two detectives on the hunt for a serial killer, but it's much more than a by-the-book crime thriller. How do you think Knights of the Shield differs from most books in the crime genre?

JF: The crime genre is typically the crime, the detective and the road to capturing the bad guy. Knights is exactly the same, except there's a paranormal twist and solving the crime is not the only journey the protagonist is on. I explore a lot of different relationship types as well, so there's a lot going on in there, more than just the crime.

SP: When you're not writing, you're working in the IT world (I barely know what that means). What got you interested in writing and how do you manage the dual roles of computer guy and published author?

JM: I've been writing since around fifteen, like I said before, but I've been telling stories since I was very young. As a computer guy, there's a lot to do in the workplace and I get it done. When I go home, I put on the writer hat and try to kick out as much as I can. Sometimes it's all crap, so it gets recycled, but sometimes I'm successful. It's tricky balancing all the requirements of fatherhood, husbanding, work and writing, but I do what I can.

SP: The cover of Knights of the Shield is filled with symbolic elements. Can you tell me what is going on with the cover image and what it was like working with a cover artist to design it?

JM: Let me answer that in reverse order. The cover designers at Pandamoon Publishing are first rate. When I saw the cover for Southbound, by Jason Beem, I was in awe. The cover for your novel, A Tree Born Crooked, just fits so well into the style of the book. Working with them on the cover of Knights was sheer joy. The main focus of the cover is a badge wallet that you'll see on nearly any cop show, but the badge holds everything in it. The religious angle, the ghostly ancestor, are both subtle. The colors were the kicker. The colors of good and honor throughout history are gold, blue, and white. The colors on my cover are perfect. The symbolism isn't quite as important as the colors.

SP: Who are some of the authors who have influenced your writing style and who do you like to read who does Not influence your style?

JM: Robert Parker is one of the best detective novelists I've ever read. He crams so much into dialogue, it's uncanny. I like that a lot because I feel it's a lot more active storytelling. Readers feel like they're actually there. That's been a huge influence on me. I absolutely love The Lord of the Rings, all those books are iconic to me. However, I could never write like that.

SP: I have to ask- what's next for you? Do you have another novel you're working on that you give us a glimpse of?

JM: I have five projects working. A paranormal drama about finding what in your life is truly valuable and is a shout out to my great Aunt Dale. She was the creator, writer, and illustrator of Brenda Starr, the comic strip that ran for thirty-plus years in over a hundred papers around the world. My project involves her characters, plus my own. I have an idea for a political thriller involving the first woman president and the plot to kill her. I have the ongoing series idea I mentioned earlier, involving a fallen angel that investigates paranormal activity and is dedicated to maintaining the balance between good and evil. I have a paranormal (see the connections here?) novel of a vampire dealing with being changed against his will and having to deal with a divorce and the possibility of losing his kids, which would be worse to him than losing his soul. And finally, a fantasy (you thought I was going to say paranormal) story about a young man's journey with mind boggling power and the balancing act he must keep between what is right and what is required of him.

Thanks so much to Jeff Messick for stopping by and be sure to check out Knights of the Shield !

Steph Post: Knights of the Shield is your debut novel and has only been out since July. Now that the book is out, how do you feel? Excited? Relieved? Ready for the next one?

Jeff Messick: A combination of everything, really. I'm really excited to finally be published; it's been a lifelong dream since I was around fifteen. Relieved that I have crossed the finish line and actually completed a project. I am already at work on five more projects, one of which will feature characters from Knights of the Shield in recurring roles for an ongoing series.

SP: Your novel focuses on the characters of two detectives on the hunt for a serial killer, but it's much more than a by-the-book crime thriller. How do you think Knights of the Shield differs from most books in the crime genre?

JF: The crime genre is typically the crime, the detective and the road to capturing the bad guy. Knights is exactly the same, except there's a paranormal twist and solving the crime is not the only journey the protagonist is on. I explore a lot of different relationship types as well, so there's a lot going on in there, more than just the crime.

SP: When you're not writing, you're working in the IT world (I barely know what that means). What got you interested in writing and how do you manage the dual roles of computer guy and published author?

JM: I've been writing since around fifteen, like I said before, but I've been telling stories since I was very young. As a computer guy, there's a lot to do in the workplace and I get it done. When I go home, I put on the writer hat and try to kick out as much as I can. Sometimes it's all crap, so it gets recycled, but sometimes I'm successful. It's tricky balancing all the requirements of fatherhood, husbanding, work and writing, but I do what I can.

SP: The cover of Knights of the Shield is filled with symbolic elements. Can you tell me what is going on with the cover image and what it was like working with a cover artist to design it?

JM: Let me answer that in reverse order. The cover designers at Pandamoon Publishing are first rate. When I saw the cover for Southbound, by Jason Beem, I was in awe. The cover for your novel, A Tree Born Crooked, just fits so well into the style of the book. Working with them on the cover of Knights was sheer joy. The main focus of the cover is a badge wallet that you'll see on nearly any cop show, but the badge holds everything in it. The religious angle, the ghostly ancestor, are both subtle. The colors were the kicker. The colors of good and honor throughout history are gold, blue, and white. The colors on my cover are perfect. The symbolism isn't quite as important as the colors.

SP: Who are some of the authors who have influenced your writing style and who do you like to read who does Not influence your style?

JM: Robert Parker is one of the best detective novelists I've ever read. He crams so much into dialogue, it's uncanny. I like that a lot because I feel it's a lot more active storytelling. Readers feel like they're actually there. That's been a huge influence on me. I absolutely love The Lord of the Rings, all those books are iconic to me. However, I could never write like that.

SP: I have to ask- what's next for you? Do you have another novel you're working on that you give us a glimpse of?

JM: I have five projects working. A paranormal drama about finding what in your life is truly valuable and is a shout out to my great Aunt Dale. She was the creator, writer, and illustrator of Brenda Starr, the comic strip that ran for thirty-plus years in over a hundred papers around the world. My project involves her characters, plus my own. I have an idea for a political thriller involving the first woman president and the plot to kill her. I have the ongoing series idea I mentioned earlier, involving a fallen angel that investigates paranormal activity and is dedicated to maintaining the balance between good and evil. I have a paranormal (see the connections here?) novel of a vampire dealing with being changed against his will and having to deal with a divorce and the possibility of losing his kids, which would be worse to him than losing his soul. And finally, a fantasy (you thought I was going to say paranormal) story about a young man's journey with mind boggling power and the balancing act he must keep between what is right and what is required of him.

Thanks so much to Jeff Messick for stopping by and be sure to check out Knights of the Shield !

Published on August 28, 2015 14:16

August 24, 2015

Booksie's Blog

Published on August 24, 2015 13:39