Rickey Gard Diamond's Blog, page 3

November 13, 2019

Time to Break Up Race and Gender Monopolies

from Rickey Gard Diamond’s column in Ms. Magazine. See them all at msmagazine.com/tag/women-unscrewing-screwnomics-series/

In a demographically changing world, uniformity is not great for business, says research regularly reported by McKinsey and Forbes. A growing body of evidence shows diverse and inclusive companies outperform heterogeneous peers. There’s no simple, causal relationship, but across business sectors, research patterns show innovation and market-share increase in companies with more diverse leadership.

Because money talks even louder than white guys at the water cooler, diversity’s now a buzzword—and on every CEO’s radar. But a common mistake is thinking that hiring a more diverse workforce is all there is to it. Any tokenism will be quickly detected, harming company retention rates, with training expensive and differences real. A recent research report from BCG on flawed approaches says, “Our data shows that most company leaders—primarily white, heterosexual males—still underestimate the challenges [their] diverse employees face.”

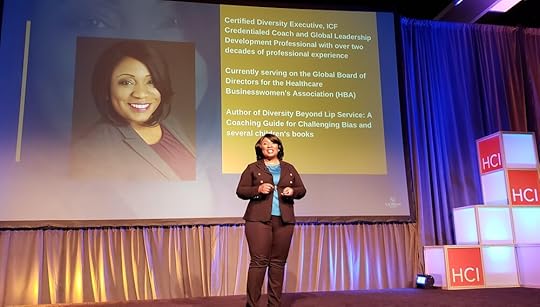

“No one has it all figured out yet,” says La’Wana Harris about the word diversity, to which she’s devoted her career. “Some talk about diversity as inclusion, or diversity as equity, but I like to think diversity is also about belonging. Belonging is a big one.” Harris is an ICF-credentialed coach who has created inclusion-awareness workshops, cultural competence programs and trainings in the U.S., Canada, Europe, Asia, and South Africa. Her new book Diversity Beyond Lip Service from business publisher Berrett-Koehler is a corporate coaching guide for challenging bias, still too often denied within male-dominated business cultures.

In 2015, McKinsey & Company reported that corporate executive teams in the US averaged only 16 percent women. According to Catalyst, an organization focused on women’s leadership in business and on corporate boards, by 2018 US women were nearly half the labor force but held only 40 percent of all management positions; often these are middle-management jobs. They noted that the higher up the corporate ladder you go, the fewer women you’ll find.

Like white men, white women still have an advantage, they note. Of the 40 percent of managers, nearly a third were white women, while Latinas were only six percent, black women under four percent, and Asians 2 percent. Far from universal, gender experience carries unique, intersectional stresses.

Unless company leaders actively pursue issues of perception, inclusion, equity, and bias, work teams may only sort out into camps or fall apart. That’s the reason corporations hire diversity coaches like La’Wana Harris to raise awareness of race, culture, and gender, while discovering deeper values, beliefs, and motivations.

In a recent interview Harris pointed out that talking diversity isn’t easy in today’s polarized political climate. People worry, she told Ms. Magazine, sharing things she’s heard from clients: “‘I won’t know what to say,’ or ‘What if I offend someone? Or ‘I kind of would like to express myself, but in this environment, I wouldn’t dare.’”

Harris said one sensible reason for inaction and silence is that people don’t want to be called out or dropped from the favor and privilege of the dominant culture. “No one wants to be excluded. What’s important is that we examine privilege and how it plays out in the power construct.”

Keynoter at Human Capital Institute’s May 2019 conference, La’Wana Harris discusses Inclusion Coaching in a talk titled, “Exploring the Radical Truth and Transformative Power that Lives within Each of Us.”

She added, “When you talk about oppression and real bias, people will go into their own corners and come out swinging and fail to find common ground. But it isn’t ‘us’ and ‘them.’ The question is how do we begin to move forward as an organization? We don’t make excuses; we don’t deny privilege. People like to talk about this in one dimension—white heterosexual male privilege— but everyone has a measure of privilege. I’m a black woman, and I’m a Christian, so I have religious privilege in America. In marginalized communities, I’m privileged by my education and my income.”

She says privilege is part of a much larger system that exists to protect power, and the unconscious biases supporting it. “That said, the goal of coaching is not to remove workplace privilege and bias, impossible anyway. Rather, let’s meet people where they are, so that they can do the self-work necessary to acknowledge their truth and how it affects their decisions. I’ll want to understand your diversity and inclusion story as a white man, too.”

White male diversity?! Does it exist? Everyone inherits a DNA shaped by a set of expectations rooted in one’s cultural context. Influences can be resisted or embraced in conscious and unconscious ways depending on circumstances and personality. Harris’s program structures, described in her book, are rooted in deep questions and self-reflection. One of the most challenging is: “What is the story you are telling yourself about….?” Fill in the blank.

Harris advises companies upfront to make room for controversy and conflict. “Tell the truth,” she says, “even when it hurts.” Just as white men don’t want their career judged as the product of unfair advantages, women and people of color don’t want to be judged as tokens to meet a quota. “As part of a team,” she says, “we all want to be acknowledged as qualified, valuable contributors. The question is, how can we use our talent and privileges to move the organization forward?”

The politically correct management perspective might be: “I am a white male, and I know that we need to increase diversity and inclusion.” But Harris insists on allowing more honest conversations, without shaming and blaming. What if mainstream management admitted something as true as: “I am a white male, and I know that in theory we need to increase diversity and inclusion. But the current power construct works for me. I’ve had a thriving career. Honestly, I don’t see what’s so wrong about that; I’m very comfortable.”

Still honesty without action amounts to lip service, by Harris’s measure. While leaders can and do discover creative ways to self-reflect and share power by welcoming differences, in a competitive world, where time and money count, diversity’s more personal work can seem at odds with short-term business objectives. In 2016, for instance, Apple shareholders rejected a proposal to prioritize diversity efforts, saying changing their leadership team, 72 percent male, would be “unduly burdensome and not necessary.”

I much admire Harris’s work and worldview, but unable to be as noble, still shame and blame. I confess I threw up in my mouth a little when in August, 2019, our biggest 200 CEOs issued a Business Roundtable signed statement, declaring “shareholder interest” or profit is not all there is to business! Led by JP Morgan CEO Jerry Dimon, paid $31 million a year, and signed by Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, who has already broken his pledge, the group’s shameless discovery of a new world of insight claims the environment and workers matter too.

Der. You think?

November 6, 2019

Do You Speak Money?

This great video from one of our favorite Cambridge University economics professors. (We also love Guy Standing, who wrote The Precariat.) Ha-Joon Chang agrees with what Screwnomics says—Economics isn’t just numbers, it’s language, too. And language and metaphors really matter.

Why? Because language not only describes what we’re talking about—it shapes HOW we think about those things and how we value them or not . It’s hard to understand how money works on Wall Street when the language isn’t familiar to you, or the language obfuscates, or tries to impress you with insider knowledge that poor-you doesn’t know. Besides, maybe Wall Street has a purpose that doesn’t match up with what you want at all.

You might not hear this often, but ultimately economics is talking about relationships. But what sort of relationships are they? This short video shows you how it works these days—so do watch it.

Still I confess I felt some cognitive dissonance between Chang’s references to “people” in this and the images you see. It’s a strange omission, or maybe a misnaming. Do YOU see a scarcity of some “people” too? HINT: It’s what Screwnomics gives a name to, exactly what’s most wrong-headed in today’s “free market” economics.

Let’s compare notes! Post your responses on Screwnomics Twitter or Facebook. What do you see? There’s no right or wrong, here, and you don’t have to have read Screwnomics I’m just wondering what you’ll think about the language and the images, what you see and what you don’t see! I’ll post my thoughts and what you said about it next week.

October 25, 2019

It Takes A Village to Raise Her Pay

Klara Martone, Burlington’s soccer team senior goalie, said her team wanted to bring attention to the pay gap. Did they ever! They’ve been on CNN, Good Morning America, and their activism has gone viral. Taking off their jerseys to reveal t-shirts saying #EqualPay got some team members penalized for breaking a soccer rule, but the girls said they’d been inspired by the US women’s national soccer team’s campaign during the World Cup this summer, and the crowd’s chanting support.

The US team’s lawsuit alleges the women’s team generated $20 million more in revenue than the men’s team while being paid only a quarter of what the men’s team was paid. The high school team has sold 2000 t-shirts and raised $30,000 so far, reports Vermont Digger. We think it matters that the team was supported by their coach, by Change the Story VT, the boys’ soccer team who also wore the shirts, and Vermont US Sen. Patrick Leahy and Marcelle Leahy, who posted pics of them wearing the jerseys, too.

It takes a village—and Title IX and a vision—to raise an assertive team of young women like these who will be tomorrow’s leaders. When the moral bankruptcy of today’s Republican party gets you down, imagine young Vermonters like these joining up with Greta Thunberg to march with Sunrise and Parkland activists. Expect a youth voting surge in 2020!

September 13, 2019

EconoMan's "Development" is Ecocide

The Amazon rainforest has been called the “lungs” of the world. Its conversion into feedlots for cattle to feed the “first world” for profit isn’t good for any humans, or for all life on earth.

Yves Smith of Naked Capitalism just published an important piece by Juan Manuel Crespo, an Ecuadorian sociologist who coins an important new word, and asks an essential question: Who is responsible for the Amazon's ecocide?

Follow the money! We need to look closer at this misnamed thing called "development," which bags money for a few, but destroys whole species and ecosystems we all depend upon. Our present economic system is not really about numbers—it is ideology and lying language. But here’s good advice from Juan’s piece, too, linked above:

If you want to preserve the balance of life, look to indigenous people. Far from being “savages,” indigenous people have knowledge and wisdom to share, the reason even our protected wildlife sanctuaries are poorer in species than the lands where they still live.

“The latest report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) recommends revisiting the native peoples for learning how to preserve critical territories. According to a study conducted by the IPCC, the areas managed or co-managed by native peoples have much higher rates of presence of birds, mammals, amphibians and reptiles than any other areas (including protected areas), which indicates that this greater biodiversity is being achieved by the practices and land uses of native cultures.

Native peoples may not exceed 5% of the world’s population, but they have preserved up to nearly 80% of the highest biodiversity areas on the planet. Ironically, they are the ones who “slow down development”. It is through the native peoples of the Amazon, and borrowing knowledge from them, that we will find the key to stopping ecocide and development.”

It’s more ideology and misused language again. We have thought ourselves superior, when we were only better armed and more violent. Unless your people came from Mars, it is far past time we “civilized” humans remember how to become indigenous natives of planet Earth. An economy waged as war, and that imagines “winning,” discounts losers, namely all inferiors like bugs, microbes, birds, fungus, diversity—and oh yes, all females, including Gaia.

Read more about the Amazon’s importance here; and while you are at it, read Riane Eisler and Douglas P. Fry’s new book, Nurturing Our Humanity. You’ll find fascinating information about indigenous people and a wider knowledge of peaceable, life-sustaining ways if only we’d look there, instead of studying war.

EconoMan's Ecocide Misnames "Development"

The Amazon rainforest has been called the “lungs” of the world. Its conversion into feedlots for cattle to feed the “first world” for profit isn’t good for any humans, or for all life on earth.

Yves Smith of Naked Capitalism just published an important piece by Juan Manuel Crespo, an Ecuadorian sociologist who coins an important new word, and asks an essential question: Who is responsible for the Amazon's ecocide?

Follow the money! We need to look closer at this misnamed thing called "development," which bags money for a few, but destroys whole species and ecosystems we all depend upon. Our present economic system is not really about numbers—it is ideology and lying language. But here’s good advice from Juan’s piece, too, linked above:

If you want to preserve the balance of life, look to indigenous people. Far from being “savages,” indigenous people have knowledge and wisdom to share, the reason even our protected wildlife sanctuaries are poorer in species than the lands where they still live.

“The latest report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) recommends revisiting the native peoples for learning how to preserve critical territories. According to a study conducted by the IPCC, the areas managed or co-managed by native peoples have much higher rates of presence of birds, mammals, amphibians and reptiles than any other areas (including protected areas), which indicates that this greater biodiversity is being achieved by the practices and land uses of native cultures.

Native peoples may not exceed 5% of the world’s population, but they have preserved up to nearly 80% of the highest biodiversity areas on the planet. Ironically, they are the ones who “slow down development”. It is through the native peoples of the Amazon, and borrowing knowledge from them, that we will find the key to stopping ecocide and development.”

It’s more ideology and misused language again. We have thought ourselves superior, when we were only better armed and more violent. Unless your people came from Mars, it is far past time we “civilized” humans remember how to become indigenous natives of planet Earth. An economy waged as war, and that imagines “winning,” discounts losers, namely all inferiors like bugs, microbes, birds, fungus, diversity—and oh yes, all females, including Gaia.

Read more about the Amazon’s importance here; and while you are at it, read Riane Eisler and Douglas P. Fry’s new book, Nurturing Our Humanity. You’ll find fascinating information about indigenous people and a wider knowledge of peaceable, life-sustaining ways if only we’d look there, instead of studying war.

September 12, 2019

Greta Thunberg Doesn't Believe in a Climate Crisis; It's a FACT.

Sixteen-year-old Greta sailed to New York like a true Viking, because aviation is a major polluter, and we humans are just about out of time to save her generation’s future. We’re in the midst of a huge extinction, losing 600 species each day, she explains to Trevor Noah on The Today Show. Where she comes from, climate talk doesn’t focus on belief; .it’s a fact. Polar ice is melting, the ocean grows acidic. Tell your Congress member that our President and a Republican Senate may be a hoax, but the climate crisis is already underway. The future looks like California fires, Houston floods, Puerto Rico and Bermuda. Time to ACT. March with Students because our future is on the line September 20th!

September 10, 2019

Sister, Can You Spare $400?

t’s time to talk about women’s economics with attitude. It’s time to laugh at what is often absurd and call out what is dangerous. By focusing on voices not typically part of mainstream man-to-man economic discourse, our Ms. Magazine series Women Unscrewing Screwnomics will bring you news of hopeful and practical changes and celebrate an economy waged as life—not as war.

In 2008, we found out just how exciting economics can be. Over 2.5 million U.S. jobs disappeared, and a third of U.S. real estate value flew out the window. It took a decade for the U.S. median household income to pass what it had been in 2008, now just over $60,000—yet, while prices go up and threaten to go higher with Washington’s trade war, 40 percent of Americans still don’t have $400 for emergencies.

Over the past 35 years, so-called “free market” changes in the rules of our money system and tax policies have moved dollars up to those already with a surplus. If you don’t have enough savings to pay for a college degree, a car to get you to your job or a house to live in, you must borrow. Businesses and governments borrow, too—and with interest reliably doubling debt, the upward movement of our system’s pyramid scheme hoists dollars to the un-needy. This is aided by Wall Street bro-bloviation, and sometimes corruption.

Interest steadfastly doubles fortunes, too. That’s the reason that we now have a record number of billionaires—2,153 worldwide, controlling piles of money estimated at $8.7 trillion.

Is this growth good news? Not when you remember that the mirror image of this class’s paper capital, the reason for its growth, is the indebtedness of the rest of us.

It’s too bad that Forbes only publishes an annual catalog of the 400 biggest fortunes. A yearly list of the 4000 biggest debtors might enlighten us more.

Mildly named “growing inequality,” these oversized lumps of billionaire numbers in the macroeconomic world affects Main Street, where most of us women work. The finance, insurance and real estate (FIRE) sector, not real economic production, now accounts for 20 percent of the U.S. GDP, double what it was in 1947. Stock buybacks and mergers that eliminate jobs are today’s most common use of billionaire surplus.

This ruthless bloating of the biggest is misnamed “economic efficiency”—an apt phrase only if your intentional goal is to melt permafrost and glaciers or develop Vermont’s Green Mountains into beachfront property.

But some capital is in Vermont women’s hands. Their numbers are smaller, but they are venturing into new territory with a wider purpose than fat cat profits.

Women are new players in the realm of capital and money. Married women couldn’t inherit property, and were property themselves, until 1848, when suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton helped win necessary legal changes to women’s statuses. Her working-class sisters couldn’t keep her own paycheck until she won that right 158 years ago. If you think sending her money to dad or husband was nuts, until 1974—just 45 years ago—banks could refuse a woman opening a bank account without a male co-signer. Even then, women needed another law to get access to business loans.

Yet women today make all the difference, says Change the Story—an alliance of the Vermont Women’s Fund, The Vermont Commission on Women, and Vermont Works for Women whose new Champions of Change campaign has already persuaded more than 140 Vermont businesses to sign on to the Vermont Equal Pay Compact pledging to improve women’s paychecks.

They also report that between 2007-2012, women started businesses at twice the rate of men’s startups. Dollar-wise their businesses are small, but even if just one in four of Vermont’s 20,786 women-owned businesses hired one additional worker, they’d create 5200 new jobs, good for the whole state’s economy. So what’s stopping them?

Small business expansion requires financing, made tighter since 2008’s crash; always it has been tightest for people of color and women. But recent studies reveal women-managed businesses make more money, so venture capital is newly seeking women out. On September 25 and 26, for instance, Vermont Innovations Commons (VIC) is hosting the third annual Vermont Investors Summit in Burlington, featuring keynote speaker Deborah Jackson, who, along with her co-founder, Andrea Turner Moffit, used her experience as an investment banker at Goldman Sachs and Citibank to create in 2015 what they call an “investors’ ecosystem.”

Their company, Plum Alley, funds women innovators and entrepreneurs “at the margins,” while also enabling women to invest in “forward-looking companies.” So far, they’ve backed startups in biotechnology, cancer immunotherapy, online marketplaces and software. Their host, Vermont Innovation Commons, calls itself a “launching pad for entrepreneurs and innovators, a nurturing partner for startup and growth firms” with a goal to create living-wage jobs and keep Vermont’s young innovators in the state. Bio-friendly terms are found on their website too, referring to Vermont’s “entrepreneurial DNA,” presumably of interest to investor ecosystems. Neither of these exists in biology, but we can hope this isn’t mere greenwashing, but a wiser way of thinking about the eco-logy in eco-nomy.

“We’re always looking out for our companies’ best interests, aggregating capital…from angel investors and other capital funds,” Samantha Roach-Gerber, innovations director at Vermont Center for Emerging Technologies (VCET), told Ms. VCET seeks to connect Vermont’s entrepreneurs to a network of peers, coaches and capital, namely The Vermont Seed Capital Fund. It, too, uses biologic words—with seed’s living reproduction connecting the green of money to their “evergreen” fund, which means its profits are plowed back into it.

The fund’s $5.1 million in revolving venture money is relatively “tiny,” yet has funded 24 startups at $25,000-$250,000 and has leveraged more. VCET’s interest is in “high opportunity businesses,” which trend to the technological, but do include women. They also co-host winter events in Burlington called Female Founders that always sell out and spark networking.

More grounded Vermont investments are in the hands of Janice St. Onge in Montpelier, through the Flexible Capital Fund. A certified Community Development Financial Institution, it provides risk capital for Vermont’s food system, forestry products, and renewable energy companies. So far, they’ve invested $4.4 million in 15 Vermont companies. What makes them different? St. Onge says she’s proudest of Flex Fund’s “royalty financing,” which is based on a piece of the revenue stream, rather than a share of equity ownership. “We remain flexible with the cash flow needs of a business and… in a way that treats our borrowers as partners.”

Vermonter Janice St. Onge, back far right, is only one of the “financial activists” who met in New York with her cohort in 2019, sponsored by the RSF Integrated Capital Fellowship program, but she and the Flexible Capital Fund are changing investment to include women and our Mother Earth. (Edith Macy)

Seeking “regenerative, not extractive businesses,” the fund values social and environmental responsibility, livable wages, and diversity in ownership, governance, and management. “The fund’s own governance is diverse,” St. Onge adds. “Four of our board of managers and two of our three-member investment committee are women.” They recently added to their portfolio MammaSez, a woman-owned plant-based meal delivery company, investing $150,000.

St. Onge is also part of a new initiative, the Vermont Women’s Investors Network, which aims to close the gender gap in funding for local businesses with positive environmental and social impact. On October 1, in Stowe, Vermont, they and the Northern New England Women’s Investors Network will host Integrated Capital—an event featuring Joel Solomon, author of The Clean Money Revolution, and Deb Nelson of RSF Social Finance, a cohort that dares call themselves “financial activists.” They even speak of poverty, rumored to be of some relevance to women.

September 4, 2019

She's Disrupting Money's Masculinity

Sallie Krawcheck, founder and CEO of Ellevest, talks with women in Denver about her favorite subject: women and money. An honest disruption of money’s masculine gaming might be good for all of us. Relationships build trust, foundational for any economy, and females are good at relationships, she says.

A sweet little girl named Sallie Krawcheck grew up in the south, and expected to get married young, but a guidance counselor she calls “weird,” pulled her into his office and said, “Look at your SAT scores, Sallie; you can do something.” That changed her mind.

Sallie tells her story in a video here. She went north, and in 1987 landed a job at Solomon Brothers, investment bankers on Wall Street. She says: “Was I in for some culture shock! The entire culture was very masculine, very testosterone driven. Every morning I’d come into my office to find photocopies of—how shall I put it? Male parts. So I’d crumple them up and keep on. I thought, hold on, I’m going to make money, I’m going to make it here.”

By 1994, she’d earned a business degree from Columbia and had become an equities research analyst at Sanford Bernstein. Her reputation, when few analysts mentioned negatives, was for uncompromising truth. Fortune magazine put her on its cover with a headline: The Last Honest Analyst, adding this clincher: she made money for her clients.

In 2002, she was hired by Citigroup’s Smith Barney, and named by Time as a “Global Influential.” She was only 38. By 2007, just as a financial crisis was taking shape, she was named CEO of Citi’s wealth management business. She said things were scary in 2008, with the biggest banks facing meltdowns, but she really thought Citi should share some of the pain with their clients. She was promptly fired.

“For me, it wasn’t about the transactions. It was about the relationships. That’s very female,” she says, and since then has made waves based on her perception that gender has a lot to do with money. In 2013, she founded The Elevate Network and acquired 85 Broads, a global network that promotes women business leaders. The next year she founded Ellevest, a company committed to ending the gender investment gap. “As I’ve looked around for things that matter, this matters!” She’s emphatic about money’s power and the importance of ethics. Ellevest’s website and its online magazine is a networking treasure for entrepreneurs and change-makers..

This week she wrote an op-ed in Newsweek that says what Screwnomics is saying! Women need to talk frankly together about money! In a capitalist country, we’ll never see women shaping power until we start talking about the ways the macroeconomy and monetary policy discounts our lives. She writes:

“A drumbeat of messages…shift the blame for women's lower levels of wealth and greater incidence of poverty onto women themselves—and away from the systemic challenges we face. If we were just better with money….if we could just get that raise….[a] blame-shifting-masked-as-personal-empowerment approach.”

Sallie’s right. There are bigger systemic issues to change! Read more at the link below. Then get together with your girlfriends and Screwnomics!

August 21, 2019

Replacing Privilege with Shared Prosperity

It’s time to talk about women’s economics with attitude. It’s time to laugh at what is often absurd and call out what is dangerous. By focusing on voices not typically part of mainstream man-to-man economic discourse, Women Unscrewing Screwnomics at Ms. Magazine online will bring you news of hopeful and practical changes and celebrate an economy waged as life—not as war.

“I never lacked for anything,” Jamila Medley says of her childhood in Brooklyn in the eighties and nineties, “but it was called ‘the killing fields.’” She’s referring to her deteriorating community at the height of the crack-cocaine epidemic. “Anything structurally and systemically wrong,” she explains, “was sent to East New York.”

Medley’s grandfather owned a property management company. Her mom was a property manager. When she was old enough, she got to work with both of them in the summers. “That’s when I learned about Section 8 processes and its paperwork,” she remembers. “It showed me grandmothers taking care of two or three grandkids with an annual income of $5000, my first introduction to poverty at that scale.” Her mom didn’t just collect rent or manage repairs: “She was a social worker.”

Later, as a single mom and college student, Medley encountered the Temporary Aid to Needy Families (TANF) program—President Clinton’s notorious effort at welfare “reform” that added yet another set of punishing government hoops to jump through to receive aid. “My view of poverty expanded,” Medley says simply. She was working with her sociology professor at Connecticut College to research women on welfare and went on to do work for a community foundation.

“There were people with resources,” she learned, “who wanted to help.” This discovery and her own desire to be of service led her to work in the nonprofit world—aiding the homeless, those in recovery or ill from cancer—while earning an MS in Organizational Dynamics at the University of Pennsylvania.

But a later position at Mariposa Food Co-op in West Philadelphia exposed her to a different model. No longer helping people, she’s now empowering them to create a thriving co-operative economy.

Philadelphia Area Co-operative Alliance (PACA) is building community trust and business savvy.

While at Mariposa, Medley served for several years on the board of the Philadelphia Area Cooperative Alliance (PACA), creating educational tools and training, before becoming its Executive Director In 2017. By then, PACA included over 20 local co-ops—including not only the most familiar type, consumer-owned food co-ops, but also a credit union, a childcare co-op, a bookkeeping business, a solar installation business, a media company, a natural cosmetics firm and a group of co-operative urban farms. Soil Generation described themselves as “a project to address displacement politics and the right to grow, thrive, and feed ourselves in Black and Brown communities of Philadelphia.”

Co-ops are sometimes portrayed in media as idealistic and crunchy-granola-headed. But Jamila and her cohorts had noticed a more painful reality in their area. Philly’s food co-ops were all white-owned and many were too expensive and exclusive for many people to feel welcomed as members. Most often black and brown people were not at the table for important collective decisions.

“All our co-ops are independent, and all have versions of food justice,” says Medley, “so PACA started our conversation by considering that one in five people in Philly are food insecure. Several of our food co-ops are in gentrifying neighborhoods, displacing black folks or poor whites. All of this is political, but also more nuanced than that,” she says, describing the difficulty of talking about race and class privilege with dynamics particular to different locations. “The important thing is to acknowledge that this displacement and poverty is happening. Let’s not ignore it. We have to interact with it—and to bridge that.”

What exactly is a co-operative? It’s a business with democratic decision-making and equal but united investment. Unlike Costco, real co-ops are owned by their customers and/or their employees, and actively engage with their local community. PACA’s website provides a surprising history of Philadelphia co-op beginnings dating back to Benjamin Franklin; a mutual insurance company started in 1752 still operates. In 1787, The Free African Society was founded in Philly, the second mutual-aid society in the US, and a precursor of formal cooperatives.

England’s 1844 Rochdale Co-op Grocery typically gets credited as first, but African Americans were ahead of the curve. W.E.B. Dubois wrote in 1900 that free Negroes were so often in “precarious economic condition” they’d created hundreds of mutual-aid societies for all kinds of shared economics. Learn more in economist Jessica Gordon Nembhard’s history, Collective Courage.

Jamila Medley told Ms. that PACA, also aligned with a larger national group, New Economy Coalition, is one of only two or three co-op alliances in the country with paid staff. Their co-op business developers are creating a promising environment for bridging racial disparities in economic terms. Ideally Philly’s co-op alliance conversations will spark other co-ops. How best to start?

“It’s important for folks who have race and class privilege to find the people who are already doing the work,” she says. “Then support their leadership. Listen and trust their decisions about who and what to fund.” Stay tuned; Jamila and PACA and a growing population pursue a united prosperity based on co-operative values.

It turns out these are also American values in need of a good dusting off—namely, self-responsibility, democracy, equality, honesty, and social responsibility. E Pluribus, Unum!

June 26, 2019

Finding My True Wealth

Inside each of us is a story of money. It is about a lot more than numbers—it is about our sense of self-worth, power, influence, and security. I had an idyllic childhood in the forest of Vermont. I was nurtured by gentle and wise parents, and my sister and I would frolic through pastures punctuated by abundant wild strawberries. I was in fourth grade when I first felt poor.

It was picture day at school, exciting for me, dressed up in my fanciest clothes. Something wasn’t right at the breakfast table. My parents were arguing, because there wasn’t enough money in the bank to cover the $24 for the large individual portraits which we purchased each year. Mom wanted to borrow money from her best friend who was wealthy; Pa refused. He was too proud.

I went to school, my enthusiasm dampened. Our small class of only ten students had our group photo taken, and then everyone but me lined up to have their individual portraits taken. I slunk off to the corner, so embarrassed. I wished I was invisible. I was so ashamed that we couldn’t afford to have this photo taken like everyone else. I felt that pain of “not enough.”

Over the years, that feeling of “not enough” has haunted me. I have seen how money divides people in society, how wealthy people have privilege, and how few people talk about their poverty, as taboo as talking about sex or death.

When I was 22, I lived in Guatemala and shopped at beautiful markets from women wearing self-woven clothing, selling their handiwork and fresh produce. There wasn’t a price tag on anything! That made me very uncomfortable. They expected me to have a conversation about what the value was. For them, the relationship determined the value. The conversation was what gave meaning, it was back and forth. It was in the dynamic give-and-take that we settled on the price and made the exchange. I grew to love this way of being more intimate with people.

I returned from Central America and rented an apartment in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, statistically one of the very richest counties in the United States. Women in fur coats and diamonds came to apply for loans at the Bank of Jackson Hole, where I was executive assistant to the vice president. One month into the job, a stack of loan documents appeared on my desk. Suzy, the receptionist, told me that the previous CEO had just been accused of embezzling $1.5 million over the last decade. It was my job to copy the evidence against him. Looking through these forged documents, I imagined him on the final day of the annual federal audit of the bank when the lies were discovered. That night he tried to commit suicide. The anxiety and shame he must have felt! The fear of being discovered! What motivates someone to do this? Hunger for more. When is enough, enough? Greed compels us to seek more and more.

I returned to college to study money and graduated with my degree in international economics from Southern Oregon University. When my $30,000 in student loans came due six months later, I was shocked. While studying economics, I had neglected my own personal finance and money management. I took a course to learn these skills, and I began teaching workshops about creating a healthier relationship with money. Almost everyone I’ve taught is suffering in some way because of money, and there is extraordinary relief when we share our intimate stories and financial struggles.

In 2010, I said yes to the hardest job I’ve ever had. It’s physically and emotionally demanding, I’m on call around the clock, and there’s very little appreciation. I became a new mother. Motherhood is one of the least appreciated jobs, truly a labor of love. I’m supported by a loving husband and have healthy children and a helpful community. The first years of my two children were the hardest five years of my life. Much of the time I felt worthless. I was doing such valuable work, but I was receiving no money and very little acknowledgment from the outside world.

I remember nursing my infant in the wee hours of the morning. I heard a rumble in her diaper, and felt a familiar wetness on my hand. I took her to the changing table, and gently wiped that mustard colored poop from her back. There was no overtime pay for this work. It’s priceless. I’m grateful for the caretakers; the men and women who care for children and elderly parents are valuable beyond measure.

My children today are eight and five, and we cooperate to care for our land and each other. In my family we fluidly balance the offers and needs of everyone as we prioritize our resource use. This flow of sacred reciprocity is at the heart of family.

I now serve as the education director of the Post Growth Institute. We bring people together to barter, buy, and otherwise share and exchange their goods, knowledge, services, and skills. I am truly wealthy, as is my family, as is my community. Nature is generous, and so are my children. So are my neighbors. Each spring I transplant into my soil perennial flowers gleaned from the land of my neighbors. I will enjoy their beauty for years to come. As these flowers burst into bloom, they are valuable beyond measure because they were gifts.

The purple irises from Rachel’s garden, the dainty columbine from Deborah, the strawberries from Amy, raspberries and sunflowers from Carrie, the parsnips from Gideon, the echinacea from Ann; they are all stretching toward the light. The beauty of these plants unfurls in the warmth of the sun and our loving care. Much like our children. We moved onto our land nearly three years ago, and each spring is like welcoming familiar friends again as the plants emerge from their slumber.

Humans are made to tend to our gardens together. Each Sunday we have some neighbors over to work in the soil and feast together. We are so nourished by this time, brought back to the roots of belonging. We belong to this land, and she provides for us. The plants living on our acre by the creek swell and decay with the changing seasons.

There is something special about being in relationship that can’t be measured in money. This is what makes life worth living. Last Thanksgiving we hosted over 30 people, some family but mostly neighbors. I looked around at the people who had brought carefully prepared dishes with such love and generosity, at the kids running and laughing and playing games, at the people playing music and having intimate conversations. I smiled as I witnessed our spirit of generosity and love, and this to me is true wealth. Honestly, we are all wealthy beyond measure.