Pam Laricchia's Blog, page 47

January 15, 2015

Refusal of the Call: Choosing to Commit to the Journey

The road so far:

Departure phase of the journey

Call to adventure: We discover unschooling and excitedly imagine the possibilities.

*****

As we begin learning about unschooling, we get very excited imagining the possibilities. Then reality hits and fear grows as we imagine going so blatantly outside the conventional education system. We waver. We wonder:

This is going to mean big changes. Will it really work out?

If it’s so wonderful, why isn’t everybody doing it?

Schools and teaching are big business—what makes me think I can do a great job of replacing that?

It’s daunting.

The myths and folktales of the whole world make clear that the refusal is essentially a refusal to give up what one takes to be one’s own interests. The future is regarded not in terms of an unremitting series of deaths and births, but as though one’s present system of ideals, virtues, goals, and advantages were to be fixed and made secure. (Joseph Campbell, The Hero With a Thousand Faces, p. 49)

This is the timeless, internal struggle between the comfort of the known path (i.e. extrapolating today’s relative contentment into the future) and the imagined rewards beckoning from the unknown path. It can be so tempting to stay wrapped in the warm blanket of our established and familiar lives. To venture beyond that means opening ourselves up to the chill of fear and vulnerability found in not knowing.

One is harassed, both day and night, by the divine being that is the image of the living self within the locked labyrinth of one’s own disoriented psyche. (p. 50)

What dangers lurk there?

Will the changes brought about by the journey be for the better in the end?

Battle for the Kingdom, Lissy Elle

Battle for the Kingdom, Lissy ElleThese questions are good. Don’t try to ignore them, turning up the excitement volume to drown them out. By exploring the questions that arise, we can find that clear purpose and deep resolve that will help us on our journey. We need to find our courage, so we can move forward alongside our fear.

When you’re feeling frazzled by the enormity of the journey you’re considering, be careful not to berate yourself. Instead, breathe. Take stock. The vast majority of things needn’t be resolved in this moment. Find joy. Even better, find joy with your children. Play. Start fresh—when you’re feeling fresh.

And remember, refusal of the call can be a valid choice, “for it is always possible to turn the ear to other interests.” (p. 49) I know I’ve encountered that situation a number of times: first introduced to something, I get curious and excited to dive in and learn more; yet upon reflection, I decide it’s not for me. At least right now. You need to have—or make—the time to commit to a journey, and strong reasons to get started.

For example, if I’d heard of homeschooling before I had kids, I don’t think I would have immediately embarked on my unschooling journey. It would have been an interesting philosophical exercise, but I had other, more immediate interests to follow. It turns out I already had school age kids when I encountered it, and the enthusiasm generated by the call to our unschooling adventure was so powerful that after only a few weeks of consideration we chose to dive in.

Of course, our paths can vary widely. I’m sure others may find the sociological and educational aspects interesting, even without kids. For example, the young adults in graduate school who are behind some of the home and unschooling research surveys that cross my path.

What if someone wants what they see as the “reward” at the end of the journey—the strong and connected unschooling family lifestyle—without going through all the fuss and challenge of the journey? I imagine they’re tempted to look for shortcuts, for “the answer.”

“Just tell me what to do. No curriculum? Check. No rules? Check. Whatever they want to do? Check. This is easy!”

They’re looking for unschooling “rules” to follow, rather than doing the work to understand the principles deeply enough to evaluate and chose their own actions. We sometime cling to rules because they are familiar. When the things we’re doing feel risky, rules can bring a measure of comfort; signposts we can rely on to keep us on the path as we journey into the unknown.

So using what they interpret as “the rules,” they imitate the unschooling actions they’ve heard about. And life might look like unschooling for a while, but then what’s likely to happen?

Can you envision the chaos?

If the only tool you have is a hammer, you tend to treat everything as if it were a nail. (Abraham Maslow, The Psychology of Science, 1966.)

As issues arise, they pull out the hammer of those “unschooling rules.” But children are unique individuals, with their own personalities, experiences, and goals. What works for one family, one child, may not work well for others. Without a solid understanding of the principles of unschooling and how they can be used (a full toolkit), they’ll be stuck using that hammer, again and again, and wondering why that reward is looking further and further out of reach.

A lot of work and experience has gone into an experienced unschooling parent’s ability to make it look easy. Easy enough that sometimes others think all they need to do is imitate the resulting actions, and they’re doing it.

If you really want the reward, take the journey. Don’t look for a shortcut.

That doesn’t mean you need to understand everything about unschooling before you get started: we learn so much by doing. Starting unschooling with your family is the beginning of the journey—the departure in Campbell’s language—not the end.

It’s up to you.

Will you refuse the call or choose to commit to the journey?

Your journey

If you’re inclined to share, I’d love to hear about your journey in the comments! Here are a few questions about the “refusal of the call” stage to get you started:

1. Did you refuse the call one or more times before deciding to embark on your unschooling journey?

2. As you were first getting underway, what did you imagine the journey would look like?

3. Did you start out looking for the “rules” of unschooling?

4. What clear purpose gave you the courage to commit to your unschooling journey?

January 8, 2015

The Call to Adventure: Exploring Unschooling

How I got here …

From bits and pieces and stories I’ve encountered over the last few years, I’ve come to imagine that the significant journeys of our lives may parallel the hero’s journey. And the unschooling journey is definitely a significant one! For the last couple of years I’ve been wanting to learn more about the hero’s journey and consider it in terms of my own unschooling journey. I’m very curious to see where it leads—if anywhere.

Yet life is busy (not full of busyness, but full of living) so I haven’t yet found time to follow this particular curiosity down the rabbit hole. Then last month as I was doing my year-end contemplation, it hit me: what about my blog? I already spend a few hours each week thinking and writing about unschooling here, why not use that existing time and process to dig into this? Yes!

My first thought was to fit it in as a monthly topic, but I quickly realized the posts would be super long. Plus I didn’t think a month was enough time to do it justice, to give it space to roll around in my mind, finding new and interesting connections to explore. Then I thought, this is my blog—it can evolve with me! Ha! So with calendar in hand and some scrap paper scribbling, I estimate that this will be a six month blog project / topic. Of course, I reserve the right the change it up if I find I have more, or less, to say as we get deeper into the journey. (See what I did there? The journey about the journey? This should be fun.)

So let’s get started with a touch of background.

The hero’s journey

Joseph Campbell analyzed countless mythological and religious stories from around the world and, in The Hero With a Thousand Faces, first published in 1949, outlined the commonalities he discovered between them. He called this the monomyth—the story, or journey, structure that underlies humanity’s rich history of stories. (The edition I’m using for page references throughout this series is the third edition hardcover, published in 2008 by New World Library, ISBN 978-1-57731-593-3.)

“It has always been the prime function of mythology and rite to supply the symbols that carry the human spirit forward, in counteraction to those constant human fantasies that tend to tie it back.” (p. 7)

Campbell describes these rites of passage as a death-birth cycle: death of an old way, conquered by the birth of something new. His point is that the symbols of mythology, the stages of our journeys, are not manufactured but are part of the innate nature of being human, part of our psyche. Though of course, there are infinite variations on the theme, hence the incredible range and depth of our stories.

That goes for our unschooling journeys as well: I’m sure there are many variations in our individual journeys, stages that some of us find more challenging, while we breeze through others, dependant on the unique set of experiences and perspective with which we start the journey.

And here we go!

The first five stages that Campbell defines make up the departure phase of the journey.

Exploring unschooling

The first stage is the call to adventure.

Our journey begins in our ordinary world. For many of us, that means a conventional outlook on education and learning: learning is the result of teaching; school is where trained teachers are; ergo, children go to school to learn. For others, homeschooling is already considered a viable option. They may even be homeschooling already, but still adhering to the conventional model of learning with teaching and curriculum. Others still may be living quite unconventional lives, but before having children hadn’t considered their perspective on education and learning.

We all start our journey from our own unique place. An individual perspective that is built upon our understanding of the world up to this moment in our lives. We’re reasonably comfortable here.

But then, something happens. Something unexpected that opens our eyes to new possibilities. As Campbell describes it, the call comes when the individual has outgrown some pattern of their familiar life. It marks a transfiguration, a spiritual passage. The herald, or “the announcer of the adventure,” (p. 44) may be a person or an event, but they are the harbinger of the journey to come.

It may even have been an ordinary event, but this time, it leads somewhere new. In fact, the herald is often an unlikely candidate for the job. Meaning not necessarily a person or event from the new world beckoning you in, but someone from your ordinary world who says or does something that, often inadvertently, sparks in you new level of awareness.

On the unschooling journey, it’s the moment when we realize that this way of learning is a possibility for our family. We decide to explore unschooling as a viable option. We have started down the path.

The call often evokes feelings of both adventure and anxiety. There’s the uneasy anticipation of trials to come, yet there’s also an inner glow of warmth and excitement. It feels like it might be a very good fit for your family. This might be “the answer” you’ve, maybe even unknowingly, been looking for. You feel the wonderful turmoil of choosing to move into the unknown: the call to adventure.

On my unschooling journey, the herald of my call to adventure was the head of the private school Joseph was attending. I can’t recall why we were meeting, or which of us had requested it, but we were discussing how Joseph was doing (we had pulled him from public school a few months earlier). I had come with a couple of printed articles and test results to discuss, and in the end she said “we’ll have to look for his gifts.”

When I left her office, I was elated. Finally, they were going to actually pay attention to him, to see him. But that evening I realized what it really meant: their environment didn’t allow him to shine either. If it did, they would have already seen the engaged and interested (and interesting) child that I see at home.

In my research leading up to that meeting, I had come across an article that had mentioned homeschooling—I hadn’t heard of it before. And it sounded intriguing.

Campbell also talks about how, when the hero is ready, the proper heralds automatically appear. I’ve noticed this throughout my life: when I’m ready for something, even if I don’t quite realize it on a conscious level, it soon appears. I don’t think it’s really the case of it magically appearing in the moment, I think it’s more that it was already there, but now I’m open to seeing it. Not just visually—we can “see” things without processing them i.e. background noise—but now I actually notice it, bring it into my mind to connect with other things.

A simple example that always makes me smile is cars. Driving around, there are lots of cars. I notice a few here and there, the odd Porsche or VW Rabbit that remind me of a couple of summers I spent as a teen at local race tracks, working pit crew and track cleanup. The amazing Batman replica car in town that I spot during the summer. But mostly, I just see cars.

And then we’re looking to purchase a car and we get a Kia. A what? I think at first. Then, all of a sudden, I notice how many Kias there are on the road. I see them in front of me at the stoplight. In the parking lot. On the highway. And I smile. Because I know that people didn’t suddenly start buying Kias en masse. They’ve been around me all the time. But it’s only now that I notice them. Just like when I bought my first car, a red Mazda 323 hatchback, and all of a sudden I noticed how many people drove red cars. Before that moment, they were just background noise.

I’m sure it’s not only me that happens to, so I just did a quick search. It’s a cognitive phenomenon called frequency illusion, or colloquially, the Baader-Meinhof phenomenon. It’s the result of selective attention: our brains are great at picking out patterns, once we’re struck by something new. (If you perceive that these new-to-you sightings are new to the world at large, i.e. are signs of “overnight success” or an incredible deal at the local Kia dealership, that’s an additional process at work, confirmation bias, where your brain lends more and more importance to each new sighting.)

So it wasn’t until Michael was interested in karate that I started noticing how many dojos were scattered about. And when he began performance martial arts and stunt training, all of a sudden I more clearly noticed all of the stunt work in movies. What before was a fist fight on a TV show, became familiar moves I could distinguish.

And once I was exposed to unschooling and the idea that learning is all around us, with that idea now spinning around in my subconsciousness, when I looked around, all of a sudden I could see it everywhere.

All that is to say, I totally get what Campbell means when he says that when the hero is ready, the signs appear. They were already there. We’re just now ready to see them.

I think it’s helpful to note that these signs from the heralds are not typically blinding, immediately understood revelations. But as we ponder the meaning of these signs (as I did the real message behind the school owner’s remark) our curiosity about this unknown world we’ve heard of grows stronger and we may find our original, conventional world feeling “strangely emptied of value.” (p. 46) Our familiar activities can begin to feel less meaningful as we’re drawn to unfamiliar, at least to us, territory.

In our minds, this uncharted world seems to hold both “treasure and danger.” (p. 48) (Ha! This may explain why I’ve always been drawn to illustrating unschooling on my website as a treasure map! You can check out the original full map here.) We hear of the strong and connected relationships experienced unschoolers have with their children and it seems impossibly delightful. We hear stories of things they do, or don’t do, and it seems almost unimaginable. I remember when I first read about things like “no bedtimes” and “eat what they want” and I thought well, we won’t be doing that bit. Perceived danger.

Yet we are inextricably drawn to this world, and the one around us now seems strangely muted, and a bit uncomfortable.

This call to adventure signals a shift deep in our core.

Are you ready?

Your journey

If you’re inclined to share, as we explore the depths of the unschooling journey in the context of Campbell’s monomyth, I’d love to hear about yours in the comments!

Here are a few questions about the “call to adventure” stage to get you started:

1. What spurred you to begin exploring unschooling?

2. Was there a person or moment that heralded your call to the adventure of unschooling?

3. Or was it an internal shift that had you considering this new world?

4. Were you already homeschooling when something triggered you to explore learning beyond a curriculum?

December 21, 2014

Seeing Learning in the Quiet Moments

When our children are younger, their energy levels are often breathtaking! They seem to go nonstop all day, jumping from activity to activity, leaving toys, games, crafts, and experiments in their wake. But as they get older, we start to glimpse quieter moments. Often just as focused, but less physical swirl, more internal contemplation.

These moments are so valuable.

They needn’t be sitting still, staring off into space. It can be a soothing, repetitive activity that doesn’t take a lot of concentration. In our house, sometimes it looked like hours on the swing listening to music. A long walk in the forest with a stick. An afternoon on the couch watching old episodes of a favourite TV show. Something relaxing and familiar, where their mind can wander. If you ask what they’re up to, maybe they say, “just thinking.” But they’re just as apt to say “nothing.”

And our society doesn’t look kindly upon those moments. They use words like lazy and apathetic.

Again, they’re seeing the surface, not the rich soil being cultivated underneath.

This time to be still is very important time. It’s where creative connections are born. This is a quote from Steve Jobs from a 1996 WIRED magazine interview:

Creativity is just connecting things. When you ask creative people how they did something, they feel a little guilty because they didn’t really do it, they just saw something. It seemed obvious to them after a while. That’s because they were able to connect experiences they’ve had and synthesize new things. And the reason they were able to do that was that they’ve had more experiences or they have thought more about their experiences than other people. Unfortunately, that’s too rare a commodity.

Yes, it’s unfortunate that it’s rare. But it’s one of the many benefits of the unschooling lifestyle: our children have the time and space to think more about their experiences (not to mention more free time to have interesting experiences in the first place).

Through this time they also come to more deeply understand themselves and their world. Their minds wander around why they like what they like, why they got frustrated last week, why their friend reacted that way yesterday, why the majority of posters in their favourite forum have a certain opinion about that thing that happened. Their self-awareness grows.

Now, that all sounds good. And makes sense. But it can be hard to trust that it’s happening in our own lives when our child seems to be doing “nothing” for days on end.

How do we start to see the learning in this quiet space?

Because yes, this learning is less noticeable. But if we are patient and pay attention over time, we can see the connections they are making.

I expect that, over time, you’ll begin to notice a pattern. After a period of quieter time, they’ll say or do unexpected things. They’ll make a comment and you’ll be struck by the depth of understanding behind it. They’ll act or react in a new way, a way that seems a bit more mature than before. They’ll add something to a conversation and you’ll wonder where they learned it.

In my experience, these bursts of growth often follow a time of pulling inward, sometimes even outright cocooning.

Even my kids themselves have noticed the pattern. I remember a time, after Lissy’s first 365 project, when she put her camera down for about six months. When she eventually picked it up again, she was expecting to pick up her skills where she left off, but soon discovered that her eye, her sense of composition and style had continued to grow during that time. She realized that the “time off” she had spent decompressing—looking at photos in magazines, books, online—had given her mind the time and space to synthesize and connect many of the pieces of knowledge and experience she had gathered over the previous year. She discovered she had continued to learn and grow, even in the quiet time. I remember that conversation well.

But it takes work on our part to allow these moment to unfold. Patience during the quiet times to give them space. Though that doesn’t necessarily mean hands off. You can bring them food or drinks or comfy blankets. Hang out and watch with them for a while. Be available if they want to chat. About whatever. Even without words you can be supportive, by being around and receptive.

The other piece is attentive observation. Noticing what is going on in their lives before, during, and after these times helps you make the connections that show you the learning and growth that is happening. That is how you can really see the immense value of these moments. And build even more trust in unschooling.

This depth of understanding, especially during the teen years, helps you deeply connect with them, maintaining the strong relationships you’ve built. Eventually it becomes even more clear that your relationships—your trust and connection—are key to living and learning joyfully together. And it occurs to you that your relationships will outlast their childhood, their compulsory school years.

And your understanding and appreciation will grow even deeper as it hits you, again, that unschooling is about learning how to live in the world, by really living in the world.

It doesn’t end. It’s life.

Here are some more posts that might connect with you:

1. Ways to Build Trust in Unschooling

2. Ways to Build Trust in Each Other

3. Five Unconventional Ideas About Relationships With Teens

December 18, 2014

Seeing the Learning in All Their Activities

Coming to unschooling, how do we begin to see the learning in everyday moments?

It’s there, but when we’re used to seeing learning through the filter of conventional school, it can be hard to spot at first. We might still be looking for someone playing the role of teacher—showing our children the “right” way to do something. Maybe we’re still looking for a studious expression of intent (“I want to learn how to do X”) and a standardized path to that end (the gathering books and videos for research and worksheets for practice). We’re probably still looking for subjects: math and reading and science. But what we’re seeing just looks like play.

And that’s not learning, right? Learning is work; the opposite of play.

Seeing the learning is our work to do, not theirs—they’re already busy doing the learning! When I began looking for the learning in my children’s everyday moments, I would ask myself questions to help me dig more deeply into their activity, past the superficial view of “just playing.” Let’s look at some of those questions.

What are they doing?

This is the most basic question. Chances are, they are probably learning something from the activity itself.

Even with a simple activity like tossing a ball back and forth, they are exploring force and gravity and physics and movement. How far can they throw it? How high? What happens with a heavier ball? Lighter? How do they adjust their throwing technique to increase their aim? Underhand? Overhand? All stuff they may try out as they play, and all experimentation that will increase their understanding of basic physics in the world.

But be careful to note: just because they aren’t analyzing and systematizing their learning, doesn’t mean they aren’t learning. So, when they are playing catch, don’t expect to walk up and ask them what they’re learning and get “physics” for an answer. Learning doesn’t need to be labelled to happen. In fact, that can get in the way. This is our work, remember? (And eventually we’ll get so comfortable knowing that they are always learning that the need to label it will fade.)

Let’s try another activity. What about a child playing a video game? Let’s dig into the possibilities:

Money management—through the game economy, they gain experience evaluating the usefulness of purchase options, making choices, and seeing how well they work out;

Map reading—through using game maps they gain familiarity with how coordinate systems work;

Reading—many unschooling kids have learned to read for the tangible purpose of being able to better play games;

Strategy—from RPGs to platformers to puzzle games to sports, they all involve strategy and each time the player gains more experience with the process of strategic thinking: (a) come up with a strategy; (b) implement it; (c) evaluate its effectiveness; and incorporate all that they’ve learned as they tweak their strategy and start the process all over again;

Facts about the world—many games include tidbits about the game topic itself to round out the world (history, mythology etc);

Art and music—some games are absolutely beautiful to watch and/or listen to, and over time players develop an appreciation for the styles they like;

Critique—whether with you, among friends, or online in forums and blogs, players share their opinions on which games they enjoyed overall, detailing the aspects they loved or felt could be improved (the battle system, the subject, the dialog, the art etc).

Really see what your children are doing. Have conversations and really listen. Don’t just gloss over it, with preconceived notions firmly in place.

What do they do next?

By noting the next step in their activity, and their next activity, you begin to see the particular path of learning connections they are following. In other words, you can watch their train of thought play out in their actions.

For example, say your child has been playing Age of Mythology, a computer game, quite a bit lately. You wonder what’s up with that. You ask and she says “it’s fun!” Then a couple weeks later when you go to the library, she picks up a book about Zeus. Interesting, you think. That’s new. It seems like part of the fun of the game is the mythology aspect. Better understanding what she’s enjoying and learning from the game can help you bring more things into her world that she’ll find really interesting. Maybe another mythology-based game. Or a movie or documentary. Or a fun website.

When you more clearly see the connections between the things they choose, you are more able to bring things into their lives that they will truly enjoy. And in turn, better support their learning.

What are they feeling?

Are they happy? Interested? Going through the motions? In the flow?

These are clues to how engaged they are with their activity, and hence their learning. If they seem bored, maybe bring out that new game or movie or trip you were saving for an opportunity. Maybe now is it.

If they are interested in something, maybe bring them more of that. More supplies so they don’t run out. Or more books/movies/games with similar content so they can continue to immerse themselves.

If they are so engaged in their activity that they are in the flow and they don’t notice much going on around them? Maybe don’t disturb them. Even discourage others from distracting them. Help them stay in the flow as long as the activity sustains it. There is so much learning in there!

How are they reacting?

Beyond the feedback about the activity itself, this is where they are also developing self-awareness and trying out different tools for different situations to see which work well for them.

Are they curious for more? Bored and ready to move on to something else? Are they getting frustrated because things aren’t going as they hoped or expected? That emotion is direct feedback about how to accomplish whatever it is they are attempting—what they’re trying isn’t working so well. In those moments, not only are they learning what works or doesn’t work in activity, they are also exploring (i.e. learning about) ways to cope with frustration.

Maybe they push through, their perseverance paying off as they finally accomplish what they set out to do. Another experience to add to their repertoire of tools to consider when things get challenging. Maybe they take a break, for an hour, or a day and when they get back to it with fresh eyes things go smoothly. Maybe they don’t. Maybe you unobtrusively bring them a glass of water to initiate a short break and some needed hydration. Whatever approach, it nets them more experience to incorporate as they build their understanding of themselves.

There are some moments that stand out in my memory.

I remember the time Joseph walked up and handed me a video game cartridge, asking me to hide it for a while. He said he was getting very frustrated with it, but whenever he saw it he kept wanting to try again. It was a few months before he asked for it back, and things we’re fine from there. It wasn’t really about the game—he was exploring and learning about himself.

And there was the time Lissy was determined to learn how to dive. It was just before dinner time when she started. After a few diving attempts of varied success, the boys were done swimming and went into the house and I believe I said something like, “A couple more then let’s go in so I can make dinner.” She did a couple more dives, and kept going. Dive. Swim to the ladder. Back to the diving board. Belly flop. Swim to the ladder. Back to the diving board. She was resolute. I thought about it, and decided not to insist she get out. Through her actions, she was telling me how important it was to her in this moment. I chose to instead make peace with dinner being later than our routine. I think she kept going for forty-five minutes! And her dives were consistently clean by the end.

I recall it was a huge aha moment for me. Her dedication and perseverance, trying again and again and again, was a shining example to me that an intense dedication to learn something could actually be internally motivated by their own goals. I was in awe. It was also an example to me at how important it was to follow their lead when possible—look where it went! True, maybe sometimes I won’t have the option to let her continue to do something as long as she wants. But by asking myself “why not?” in moments like these over the years I’ve found that, more often than not, I really can.

Taking the time to dig into the roots of your children’s every day activities can help you discover the learning that is happening All. The. Time. And the conventional school filter will soon melt away as you see them explore and engage with the world around them.

It’s really a beautiful thing to witness.

Want to dig more into these ideas? Try these posts:

1. Unschooling Doesn’t Look Like School At All

2. Learning to Read Without Lessons

3. Math is More Than Arithemetic

November 30, 2014

The Search for Meaningful Work

As we’ve looked at this month, coming to unschooling as adults is a fascinating journey. Chances are we’ll revisit our childhood and realize that play isn’t “just for kids.” We’ll discover that learning isn’t something you do in preparation for adulthood—at its best, it’s a lifelong activity. We’ll reawaken our curiosity, eagerly pursuing what we don’t yet know, rather than trying to hide our lack of understanding in shame.

So what’s left?

For me, it was to take my new perspective on learning and living and apply it to that other significant chunk of my life: work. Or more exactly, what I choose to do with my time, woven in with earning money for food, shelter, and the necessities—and joys—of life. Once we break away from the societal imperative of school, it’s not long before the “9-5 job to earn money to buy more things” paradigm comes under our scrutiny.

As the principles of unschooling begin to spread into every nook and cranny of our lives, we discover the joy and power of making our own choices. Of doing what is important to us, rather than what we’ve always been told to do. We begin to ask those questions of all areas of our lives. Is what we are choosing to do with our lives meaningful? Does it bring us a sense of purpose? If not, what will?

And we want to find the answer to that question. Now.

But here’s the challenge: that’s still conventional thinking clouding our thoughts, that there is a “right” answer. “What is my dream job?” The job that will bring fulfilment and meaning to my life and make every day a joy to get up and go to work. Not to mention the need for immediate gratification: “I need to figure out what my passion is asap.”

Another thing that might trip us up is that I think sometimes we conflate joy with ease. The work that brings us joy—a deep sense of purpose and meaning—may be some of the most challenging work we do.

One of the most significant things I’ve learned over the years is that I will grow and change. It dawned on me that making a different choice today does not mean that my earlier choice was wrong. And the awesome thing is, I learned this from watching my unschooling children live with the freedom of choice. I saw their choices change over time—yet each time it was the best choice for them in the moment. What happened was that their perspective, understanding, and/or goals changed over time.

And I realized this was just as applicable to me as it was to them. It’s a human thing, not a kid thing. Looking back, I saw my perspective, understanding, and goals changing over time. I wasn’t wrong before; things are different now. And projecting that understanding into the future, I realized that the choices I’m making today may not fit forever. That was a huge piece of the puzzle for me! It released some of the expectation and pressure on my current choices; they no longer have to be “the answer.” Changing my course doesn’t mean I failed. I was learning more about the world, and myself. It’s a journey, not a destination.

I love the idea of thinking of our lives as a body of work, and recently enjoyed reading Body of Work by Pamela Slim. Here’s her definition: “Your body of work is everything you create, contribute, affect, and impact. For individuals, it is the personal legacy you leave at the end of your life, including all the tangible and intangible things you have created.” (And as an aside, I smiled as I read her dedication, “And for my mom, who has taught me that cultivating a happy, healthy, secure family is a work of art, and a revolutionary act.”)

Let’s branch here. It’s pretty typical in unschooling families (ha!) for one adult to take on the day-to-day parenting and unschooling tasks while the other takes on a job to earn money. Both are work. Both are what we are choosing to do with our time. So now I’m going to talk about each of these roles. Granted, especially with unschooling families, the brilliant thing is that there can be all sorts of machinations around work: maybe both parents have jobs with alternating hours, taking turns at home; or maybe one or both parents work from home, or mostly from home; or there’s only one parent actively involved. Whatever a family’s approach, there will be some combination of these two roles.

the money-earning job role

I think one of the most helpful things to do when you start looking more deeply at this role, is to shift your perspective away from “have to” toward “choose to.” Like we shifted away from the conventional idea that “kids have to go to school.” Really, it’s a choice. We can think so much more clearly and creatively when we take back control. When we aren’t feeling trapped by circumstances.

For example, if you’re feeling trapped by your job, it can help to go to the extreme end of the spectrum for a little wake-up jolt: yes, your family probably has fixed expenses for shelter and food and transportation etc, but you’re choosing to stay, choosing to go to work. You could theoretically wake up and leave tomorrow. No? Still choosing to stay? Great!

With choice firmly back in play, next it can help to take a moment to think about the positives of the time you spend at your job. Enjoying the work itself is only one reason why a person might choose to work at a particular job. What are you getting out of your job? Are you learning new skills that will help you later in your career? Is the product or service provided by the company you work for satisfying a need of its customers? Can you see value in that? Are you earning money that supports your family? Can you see value in that?

Find the value in what you are doing now. It’s a great starting point when you’re searching for meaningful work. It gets you digging into your values, into your goals. You’re building a body of work. Look back and find the common threads that run through the different jobs and interests you’ve had up to now. What drew you to them? Those will be clues to help you define what is meaningful for you.

And going back to the idea of a “perfect” job, whether you want to work for yourself or someone else, I think that the search for “perfect” can paralyse us. Remember, it’s a journey. Take a step forward that seems to be in alignment with your goals and see what happens. Still look good? Take another step. Not so much? That’s not failure, it’s learning. (That’s what you tell your children, right? It applies to you too.) Change direction a bit.

Take small, meaningful actions and stay open to the possibilities. It’ll bring you more information to play with and help tease out the next step to help your work align with your goals. In my experience, after a couple of steps, we often discover something wonderful that we couldn’t even have imagined two steps back.

One other thing to note: there’s nothing wrong with choosing your most meaningful time to be when you’re away from your job. Maybe, at least right now, your job is a means to an end: it’s about earning money to support your family and enjoying the time you get to spend with them. Nothing wrong with that. The point is that it’s your choice.

By choosing an unschooling lifestyle you’ve already shown yourself to be an independent thinker, someone not tethered to convention for convention’s sake. Bring that creative and open perspective with you into the world of work.

the stay-at-home parenting and unschooling role

The at-home parent has likely done, or is in the midst of doing, a lot of soul-searching to be at peace with making what is currently a very unconventional choice: staying home to raise a family.

Before I left my job, I did a lot of soul searching, a lot of digging deep to truly understand what my goals in life were. Who was I without my job? And what was the job without me? Who was I if I didn’t have a nice, pat, and impressive answer to that ubiquitous question, “What do you do?” Were all those years at university “wasted”? Was I “throwing away” my degree? All those guilt-inducing phrases that get tossed around.

To summarize those many hours of turmoil, I came to see that just because I was changing course, didn’t mean those years down a different path were wasted. In fact, those experiences were tightly woven into the person I was today. The person who was now seeing leaving my job as a viable, and fantastic, choice for me and my family, one in alignment with my personal goals.

As I dug into my concept of work, I realized the measure of work is not salary. It’s in meeting my needs and goals. Actually, it’s meeting my family’s needs and goals. Earning money is not a goal in itself—money is a tool to help us meet our needs and goals.

And in the end, I realized that choosing to stay home and actively be a part of my children’s lives did not mean I “wasn’t working.” I am choosing to spend my time, energy, and talents being intimately involved in my children’s lives and learning—that is meaningful work.

And doing it well is my goal.

Remember above when I was talking about taking small, meaningful steps and staying open to the possibilities as you move toward aligning your work with your personal goals? That process works very well for the stay-at-home, unschooling-focused parent as well! And Sandra Dodd’s mantra just popped into my head: “Read a little, try a little, wait a while, watch.” Sound familiar? I love when these ideas mesh so well. Don’t rush, move forward with intention. Keep learning. Keep observing. Re-align your next steps to incorporate your new level understanding of your goals and ways you might meet them.

As my children have gotten older and parenting and unschooling take up less of my time, my meaningful work is morphing again—my body of work expanding. For example, here, with this blog. Unschooling has had a profound impact on my life, and sharing my thoughts and experiences surrounding unschooling with other people interested in exploring this lifestyle feels meaningful to me. And being open to the possibilities, through writing about unschooling I’ve unearthed a deep love for writing itself. Now I’m also starting to play with fiction. A few years ago I could hardly have imagined that. Did I mention it’s a journey? Definitely.

So how is your unschooling journey unfolding?

November 28, 2014

Excavating Our Curiosity

I touched on this a bit last week, in the childhood we wish we had, discussing a couple of solid reasons to play with our children now, as adults. But that’s just a start at excavating our buried curiosity.

How did it get buried? Most of us grew up enmeshed in conventional schooling and parenting, where our learning at school was directed by curriculum and teachers, and living at home was directed by our parents. We didn’t have time to discover and pursue the many things in the world that we were potentially curious about—our interests were far down the family’s list of priorities. We were promised that “we could do what we want when we were adults.”

So we grew up. We began questioning the conventional wisdom surrounding parenting and schooling and now, as unschooling parents, our days are focused on nurturing our children’s curiosity, not burying it. We delight in helping them discover the joy and wonder that accompanies an inquisitive mindset, and the incredible learning that inevitably follows.

What does that look like?

When our kids are younger, they need more of our immediate attention and ongoing care. We are with them, their extra set of capable and reliable hands. We build that tower over and over and over, and bask in their delight as they knock it down … over and over and over. We answer their seemingly unending stream of questions. “What is that?” “Why does that happen?” “How does that work?” “Let’s find out!” Learning at this stage is a joy to watch. It’s unfolding before our eyes, visible for anyone to see—if they pay attention.

As our children get older, their learning becomes more internal, less immediately visible. Now it sometimes takes a different kind of effort for us to nurture their curiosity. We fall back on our intellectual understanding of the value of curiosity, using that as our motivation. We remind ourselves to help them gather supplies for their project instead of discouraging them from making messes; to drive them to their activities or host their friends rather than hitting the couch. It’s a mental exercise we do to convince ourselves to keep going. But, in my experience, that only gets us so far. We’re just playing the part.

But when we become curious creatures? Then things really start to shine!

I remember when we first came to unschooling and I mustered an interest in everything that came along—but that wasn’t sustainable because it wasn’t me. Over time I noticed that when I was truly interested in something, my curious and engaged attitude was deeper and more joyful than I could ever “fake.” It was fun! I wanted more of that. So I began to more widely explore the world, and myself. To follow my curiosity and see where it led me.

It took some time. This wasn’t something I was used to doing. I was used to staying in what I already knew, my “areas of expertise.” That’s what I learned growing up: gain compentence and stay there. To be a beginner at things was painful at first! We are so accustomed to being shamed for not being good at something, or not knowing something. But unschooling is an entirely different way of life—the discovery that you don’t know much about something is full of possibilities, not shame. “Do I want to know that?” “How can I figure it out?”

But remember, don’t do this in a vacuum—share! Not necessarily the knowledge (though by all means that too if your kids are interested in the same topic), but the process. This exploration is what your children are doing as well! Mention how you find new information. What you do when things get challenging. The fun you’re having. What you find so interesting about it. How it connects to other things you know and love.

As curious adults, we exemplify the joy of digging into things we don’t yet know or understand. When your child comes to you to share their excitement over figuring out something new in their game or how they fixed their toy, your connection with them isn’t just over “cool, you did it!” but a deeper, stronger connection surrounding the joy of discovering new knowledge or skills. And that doesn’t happen unless you are discovering new stuff too.

Side by side, you and your kids will discover that some interests come and go, while others may show no signs of abating. You’ll explore the many ways to gather information and connect with others who share the same interest. You’ll examine different ways to handle challenges and frustration. You’ll unearth the connections between different interests, learning more about what makes each of you, uniquely you.

I bet you’ll also come upon times of restlessness, as an interest wans while nothing else has yet grabbed your attention to take its place. Sometimes in those moments we might describe ourselves as bored. I like Leo Tolstoy’s definition of boredom: “The desire for desires.” Yet as we and our children cycle through those times over the years, we learn more about ourselves yet again. We learn to trust, to know, that something will appear in time. That those moments are as much a part of the ebb and flow of life as those times when we are intensely focused. That though we may not be actively pursing something, our minds are still processing and connecting and growing.

For example, sometimes the passage from childhood into the teen years is accompanied by a transition of interests—the games and activities that engaged them for so long are no longer as interesting, while they have yet to find new interests and passions to absorb their attention and engage their expanding view of the world. There may be a period of listlessness, or cocooning, as our children move through this time. When we’ve experienced these transitions ourselves, we can often be more understanding, more supportive.

Here’s the question: Who do you want to be today?

Deeper than your role as parent or adult—fundamentally, as a person. Do you find the world interesting? Do you want to better understand the pieces of it that catch your fancy? Are you apt to pursue that tug of curiosity? To engage in exploration and discovery? The zest and passion for life that we see in our unschooling children is ours for the taking too!

We share things with our children. They share things with us. It becomes part of our family culture.

It’s unschooling.

It’s life.

Related Posts

2. “Who Am I and What Makes Me Tick?”

3. “If You’re Bored I’ll Give You Something to Do”

4. Curious and Engaged—HSC conference talk

November 17, 2014

The Childhood We Wish We Had

As part of exploring and understanding unschooling, we think long and hard about our own childhood:

our learning experiences (in which situations did we learn more? remember more?);

our school experiences (how much long-term learning? how much stress? did we use what we learned?);

the atmosphere in our home growing up (rules? punishments? pressure? control?);

how supportive our parents were (who chose what we did day in and day out?);

and generally, how do we feel it turned out for us?

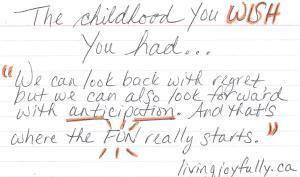

Sometimes there’s a pretty stark difference between the childhood we lived and the childhood we envision for our own children with unschooling. And as that realization dawns, we can be left feeling sad, mourning for the childhood we wish we had.

Then maybe the thought occurs to us that, certainly for most of us, our parents were doing the best they knew. Which is what we are doing now. And what our children will do in the future, if they choose to become parents.

Certainly we can look back with regret, but we can also look forward with anticipation.

Certainly we can look back with regret, but we can also look forward with anticipation.

And that’s where the fun really starts.

We can incorporate our adult understanding of our childhood experiences into the environment we choose to cultivate for our children. We can re-experience childhood, not only seeing it in a new way through our children’s eyes, but engaging in it alongside them.

We can play with child-like wonder with them. It’s not just for kids!

You will learn so much.

Lifelong Learning

So here was my opportunity to get my fill of those childhood activities I loved but didn’t have enough time to explore. Colouring. Building with Legos. Kicking a ball around. Playing catch. Making goop! Cartwheels. Games, games, games. I still haven’t figured out the hula hoop.

If there’s an activity or a game you remember wishing you had played as a child, bring it into your lives now. Not only will you guys probably have lots of fun with it, it will help you explore the idea of lifelong learning. You’ll discover that there really are few things that are strictly “for children only.” Height restricted rides at the amusement park come to mind.

We have a lifetime to experience, well, life. Does it really matter that we didn’t shoot baskets to our heart’s content until we were in our thirties? Will it really matter if our child isn’t interested in the periodic table until their thirties?

See what I did there? Your understanding of the principles of unschooling will deepen as you play with your children and observe what happens. So don’t spend your time wishing you had done X when you were a child—do it now. Give that younger version of you a virtual hug and invite them along.

Engagement and Flow and Play

For me, as I watched my children in action, I found their deep engagement in whatever they were doing stunningly beautiful. That was something I was keen to get back, even though I was no longer a child.

I lost that capacity pretty early. School bells told us to stop and move on, at arbitrary times. Parents told us to stop what we were doing and do what they wanted us to do, on their schedule. With a conventional childhood, we learned early that our time was not ours to control and without wide swaths of it to sink into our exploration, we stopped losing ourselves in the deep engagement and flow of our activities.

But playing alongside my children helped me re-awaken that sense of immersion in a task. The ability to sink into the flow of an activity where an hour feels like minutes. It’s like the fun house mirror of time.

Eventually I began to realize the deep, soul-crushing impact of the seemingly simple message we absorbed growing up: work is work (and school is work) and work is not fun. I began to see that “play” is NOT a dirty word. That I could approach work, and life, with a sense of play, a sense of exploration and discovery. That work could be fun.

When we approach our work—our day—with a playful attitude, it’s amazing what happens. We feel more imaginative, more engaged. Lighter. Our minds are more receptive and agile and creative. And not only is the time more enjoyable, what we accomplish is often better than when we approach our tasks with adult-like seriousness and expectations.

“Work and play are words used to describe

the same thing under differing conditions.”

~ Mark Twain

It’s hard to remember that when I’m embroiled in a never-ending to do list, but it’s such a revelation each time I do.

So instead of feeling stuck mourning the childhood you wish you had, have it now! Just because you’re an adult doesn’t mean you have to toss the playful and engaged approach to each day that marks childhood—and that conventional society works so hard to drum out of them. Play isn’t just something kids do.

It’s life.

November 11, 2014

Can You Teach an Old Dog New Tricks?

A few months ago I was in conversation with someone and we ended up at the old saying, “you can’t teach an old dog new tricks.” Us adults being the “old dogs,” of course. It was someone I enjoy speaking with and during the course of our conversation, a couple of light bulbs went off for me about learning and how our unschooling lifestyle may be perceived by others.

Are adults set in their ways?

Well, it’s likely we have some pretty established habits—thoughts and actions we’re comfortable with and return to—if for no other reason than we’ve been doing them that way for so long. We probably have beliefs we haven’t challenged in a while: what’s the point of re-visiting something we’ve already figured out? Besides, change is hard. So I can understand what she was implying when she used the phrase.

But I think we can continue to learn throughout our lives—if we’re interested. I continue to learn new things as I approach my fifties. The list of topics I’m excited to learn more about at some point is long! And I find questioning my beliefs and habits once in a while a refreshing exercise: do they align with the image I have of the person I’d like to be?

Being curious about the world and engaged in the lives of those we love is an invigorating way to wake up every morning, young and old.

What’s the difference between supporting someone’s learning and coercion?

Another piece of the conversation I found absolutely fascinating was the implication that by trying to support change in another adult, I was really trying to coerce them, because adults are set in their ways.

It was interesting to see that the actions I was talking about were assumed to be motivated by me, instead of by the other person. Oops. Though I shouldn’t have been surprised by that conclusion—trying to change others to match our own expectations is pretty common practice. So often adults try to sculpt not only their children, but their spouse and their extended family members as well, trying to match the “perfect” picture of those roles in their mind.

Yet people are individuals, not the roles they happen to inhabit. And they grow and change. As unschooling parents, we can support both our children and our spouse/partner as they explore and decipher the person they want to be and ways they might move closer to their own ideal.

I know we often see things quite differently as we look at life through the lens of unschooling, but it can still surprise me when the motivations attributed to our actions by more conventional onlookers are almost diametrically opposed to our reality. To conclude I’m coercing others to learn or act in certain ways against their wishes? “No way!” is my first thought. Yet that feels dismissive, uncomfortable. My curiosity soon bubbles up. It doesn’t hurt to take a moment to recheck my motivations, nor to confirm that my support isn’t being felt as manipulative, and that it’s still wanted. All good?

These moments do remind me that helping my family do things they want to do, can sometimes look on the outside like I’m “making” them do them. Take something as simple as a teen hugging a parent good bye. The typical conclusion from onlookers? Obviously the parent expects/requires it and is using some level of guilt to receive it because no teen wants to do that. So much of our unschooling lifestyle looks like one thing to outsiders while the actual motivation behind the actions is entirely different.

In those instances of misinterpretation, what seems to have worked best for me over the years is to not react defensively. If asked, a quick answer will do. “Nah, she doesn’t have to hug me good-bye, she wants to.” To not get pulled into trying to explain myself, even if I see disbelief written all over their face. Of course they see it the way they do. Instead, I let time work its magic. Show, don’t tell. Over time they see the action repeated in different contexts and their understanding of the real motivation behind them grows.

That’s real learning, real understanding, rather than me blabbering in their ear.

Moving to unschooling as adults

For adults, us “old dogs,” moving to unschooling can mean a lot of personal work. We sift through so many of the conventional messages about learning and parenting and relationships we’ve absorbed over the years, seeing how they hold up against our own experiences and goals. We re-visit our beliefs, our habits, our vision of the person we want to be. This deschooling is not easy work.

But it’s worth the effort because it’s those deep roots of understanding, along with the strong and connected relationships we develop with our family as a result, that carry us through those moments of disappointment when our lives are misinterpreted by those around us.

And in the end, which is more important: that an acquaintance or extended family member gives us the thumbs up, or that we live our lives the way that makes the most sense to us?

October 31, 2014

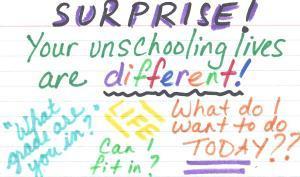

When Unschooling Children Discover Their Lives Are Unconventional

As unschooling parents, we’ve chosen this unschooling lifestyle for our family. In doing so, we decided that although it’s unconventional, the benefits outweigh the challenges. Or else we’d have chosen to stay on the conventional path, so well-trodden by those before us.

Yet at some point as our children get older, they will realize that their lives are quite different from many of the kids and families around them. In my experience, for the most part, they’re pretty cool with that! They have real control over their lives and can choose what to do with their time. Yet there can be times when living an unconventional lifestyle can feel frustrating and burdensome.

What can we do if our children express disappoint or fear as they discover their lives are outside convention?

The feeling of being an outsider

Sometimes living outside the majority can feel lonely. Maybe they join a local activity but soon find themselves out-of-step with the other kids after answering “I’m homeschooled” to the ritualistic “what school do you go to” question.

And, whereas an unschooling child is there by choice and interested in learning, it’s not unusual for many of the other kids to be participating in the activity at their parent’s behest. Which usually means they aren’t particularly keen to pay attention or participate. Yet another way unschooling children may feel out-of-step with mainstream attitudes.

You can help your child feel more in control, and less fearful, of these moments by doing some prep work beforehand. You could chat about typical questions and come up with possible answers they can use. Maybe you work out what grade they’d be in based on their age to answer that other seemingly universal question: “What grade are you in?”

“I’m homeschooled, but in school I’d be in grade five.” Help them find ways to build a quick bridge of connection with kids who are living more conventional lives so they can ease into activities and feel less like an outsider.

“I’m homeschooled, but in school I’d be in grade five.” Help them find ways to build a quick bridge of connection with kids who are living more conventional lives so they can ease into activities and feel less like an outsider.

It can also help to remember that many children living a conventional lifestyle feel like outsiders sometimes too. Maybe chat about TV shows or movies you’ve watched together where a child character, who most likely goes to school, has felt like an outsider. It’s not something that’s precisely defined by the choice to go, or not go, to school.

And as moments arise in conversations, as they inevitably do, you can mention some of the reasons why you chose not to “play it safe.” What it was—what it is—that makes this unconventional lifestyle so important to you. Connect these bits and pieces of the world as you see them out loud in a sentence or two, and see where it leads. Maybe further conversation in the moment; maybe a connection they make on their own next time they’re listening to music on the swing, or next time they see a similar situation play out around them.

See the world through their perspective so you can better support them as they play with the idea of conventional and unconventional and dig into what the roots of “feeling like an outsider” are for them.

And don’t forget to remind them that it’s absolutely okay to be different!

The challenge of running our lives

Though unschooling children will definitely appreciate the freedom to learn in their own ways and to choose how they spend their days, at some point(s), they may start to feel overwhelmed with it all. Every so often the thought of someone else telling them what to do can be comforting. To be able to just do, rather than having to think and analyze and decide before doing.

It’s the same for us adults! Now and again, don’t you wish someone would just give you a foolproof plan to follow so you don’t have to figure out yet another thing for yourself? “Do steps 1 through 5 and I guarantee you will accomplish your goal!”

That feeling of overwhelm is a very human thing to experience. Regardless of age.

The bonus is, as unschoolers, we have the time to help our children work through these feelings; we don’t have to quickly sweep them away so they can get their homework done. We can listen. Validate. Commiserate. Share our own experiences. Show compassion. Let them know it’s okay to feel sad or disappointed or overwhelmed.

And when that happens it doesn’t mean that unschooling has failed. Unschooling isn’t about life being “perfect.” It won’t be. But I’ve come to see that the time we spend with our children working through their hurts and fears and sadness is such valuable time! Certainly just as worthwhile as the time spent discussing facts and developing skills. Gaining experience and learning the ways that work for each of us individually to process the myriad of emotions that a full life has to offer is priceless.

Unschooling is life.

October 28, 2014

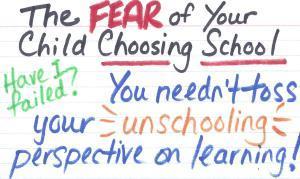

The Fear of Your Child Choosing School

What if my child wants to go (back) to school?

What if my child wants to go (back) to school?

It’s a fear I’ve seen come up online pretty regularly, and one I experienced myself a couple of times in our first few years.

I still remember it clearly, that rush of fear and adrenaline when one of my kids mentioned they were considering school. All of a sudden, questions were spinning through my mind like a tornado: Why are they interested in school? Is our unschooling home not good enough? Is this a judgement of me? Have I failed them? Will those who thought I was crazy to take them out of school see it as proof they were right? What if they go to school and don’t fit in? What if they are really behind? Will teachers and other parents look down on me as an bad parent?

I had enough presence of mind left to realize that when I’m feeling judged and defensive is not a good time to try to have a conversation (“What?! Why?”) or to make snap decisions (“You’re not allowed to go to school!”).

But it is a good time to breathe. Deeply. Slowly. Have a glass of water or a cup of tea. Let some time pass. Do the things that work for me to dissipate the adrenaline and move into a clearer frame of mind.

And then, when I had a moment here and there, I asked myself, “What was I really scared of?”

It wasn’t easy, or pretty, to tease out the many knots that were woven into my fear, but eventually the thought stopped sending me into a tailspin (although sometimes I still needed to talk myself through a knot or two again, and again). So I thought we could dig into some of those knots together.

One knot was the fear of being judged by others

Even though choosing unschooling for my family was pretty easy (it made sense to us and my kids were excited to be home), it was sometimes challenging once I stepped outside. It takes a lot of thought and energy and commitment to choose an unconventional lifestyle. Extended family and friends directly question your choice to keep your children out of school. And then there’s the ever-present societal messages, like “children need to stay in school or they’ll never amount to anything,” wafting around you. With that added pressure, we can often feel like we have something to prove to our naysayers, and that can pull our focus away from our family.

Most of us have been conventionally raised to see a reversal as a condemnation of our initial decision: If you make a choice, and then in the future make the seemingly opposite choice, those around you are apt to conclude that your first choice must have been wrong. That you were wrong. You made a mistake. You failed this unschooling experiment. We feel transported right back to our childhood where mistakes were a bad thing.

In that rush of shame and fear of feeling judged as “wrong,” we often forget what we’ve discovered about learning since starting our unschooling journey: that judgement deeply interferes with real learning (our learning too). That when things take an unexpected turn (most often a much better description of a situation than “wrong”), we can learn so much. And our experience is incorporated into our future choices. Real and lasting learning. I realized maintaining that atmosphere is my goal. Not being “right” in the eyes of others.

Then I asked myself, do extended family and friends—people observing, but not living, our lives—really know what’s going on? Is it as black and white, as right and wrong, as they seem to think? Soon I realized the reality I see is much different. Putting myself in their shoes I can see why they might draw the conclusions they do, but that doesn’t mean they are right. I understand the bigger picture of the learning that is happening in our family, and how my child potentially choosing to go to school isn’t a mark of unschooling failure so much as an extension of the learning lifestyle we have chosen.

So again, as when we first chose unschooling, I could choose to be strong in my family’s choices.

Another knot was the fear of failing my children

Was I failing at unschooling?

It’s good to regularly ask ourselves if we are doing all we can to support our children. Just remember to ask the question from their perspective—it’s not, “Do I think I’m supporting my children?” but “Do my children feel supported?” A subtle but important distinction.

So if your child expresses an interest in school, what if you chose to explore your child’s curiosity about school with them?

Over the years I’ve heard stories where what the children were actually interested in was riding a bus, or eating from a cool lunchbox, or playing with friends at recess, or doing workbooks etc. In their mind, those activities were associated with going to school, so that’s what they asked for. School might just be the answer they’ve jumped to, not the root of the interest itself.

If that’s the case, you may discover ways to satisfy those interests without resorting to registering for school, like taking bus rides around town (have fun figuring out maps and bus schedules together), letting them pick out a lunch box and filling it with fun food (play with finger foods, bento boxes etc), making more regular play dates with friends (maybe host weekly game drop-ins, or plan a fun themed party), taking them to the bookstore to pick out some interesting workbooks (and letting them use them however they’d like).

Whenever I became concerned that one of my children may want to go to school, instead of wallowing in my fear of failure, I used it as a trigger to ask myself if our unschooling lives were as interesting as they could be. That helped me shift my perspective from negative to positive, reminding me of this lovely quote from Anne Ohman:

How can I connect with my children today, expand their worlds, bring joy into their lives, nurture and encourage what they love to do?

A third knot was the fear of bringing school into our lives

As I dove into this fear, I realized that even if they do choose to try out school, they would be going with a very different perspective than the vast majority of students. The school experience is so different when our children choose to be there because, for them, school isn’t compulsory. We can let them know that if they find it’s not for them, they can choose to stay home again.

The question for me became, how much does school need to permeate our lives?

If they make the choice to be there, we can support them in getting out of the experience what they are looking for. Our perspective on the experience can stay firmly in sync with them—we don’t need to “shift allegiances.” We can continue to see the whole world as our learning playground. We don’t need to become the school system’s eyes in our own home.

If you think you might feel a pull to do that, to begin nudging your child to finish their homework and judging their test marks, ask yourself why.

Maybe you feel that your unschooling will be judged by how well your child now does in school. That teachers will look down on your child for not being at “grade level.”

Well, maybe they aren’t at grade level as per the school’s curriculum, but that doesn’t mean they haven’t been learning. I bet they know lots of things that, even though they aren’t part of the curriculum, are important pieces of their world, of their life. They probably already know things that will come up in the next grade, or the next. You don’t need to buy into the attitude that what’s in the curriculum is far more important than what isn’t.

Just because school is in the mix, you don’t need to toss the philosophical perspective on learning you’ve developed on your unschooling journey.

For example, the idea of lifelong learning. That learning can happen at any age, that all learning is valuable in building our understanding of the world. With unschooling, the parameters of your child’s learning were wide—much wider than a curriculum. That doesn’t have to change.

If you think of school as a tool your child is trying out as they pursue their goals, you can keep the lifelong learning perspective rather than zeroing in on learning defined by grade. Curriculum is just a tool the school system chooses for efficiency, it’s not the definitive word on what to learn. That constellation of knowledge and skills is unique to each of us.

Or maybe you’re feeling a tug to make school as unhappy an experience as possible in hopes they’ll choose to come back to unschooling. If I recall, that was my first reaction to the thought of one of my kids returning to school. For example, nagging them to do homework with the ulterior motive of making school seem annoying isn’t being very supportive nor considerate of your child’s choices. If not doing homework has consequences, those are school consequences, they needn’t be yours.

It didn’t take long for me to realize that my urge to emphasize school’s unpleasant side was a reactionary stance rooted in the feeling that their choice would somehow be an explicit rejection of our unschooling lives up to that point. Would that be helpful? No, that would make their choice all about me, not about them. I would be the one adding judgement to the mix.

Why might we tempted to do that? Because that’s what we grew up with. But our unschooling children don’t live every day in a pervasive cloud of judgement. They feel in control of their own lives, not manipulated through judgement and shame by those around them. Instead, their choice to try school will be rooted in their current perspective, their goals, and the various ways they might meet them.

And adding school to your lives, with its system of grading and sorting, needn’t shift your perspective on judgement—it’s not about going back to old ways. Especially if you’re concerned that school may not a be supportive environment for your child, keeping the judgement out of your conversations and the communication channels open is key. If you make the choice to try out school about anything more than them exploring their options, it can quickly get tangled up in a power struggle.

If your child gets the impression that you consider their school choice as them choosing school over you, you set up any future choice of theirs to leave school and return home as your “win” and their “failure.” And it’s so much harder to make a choice that feels like failure, isn’t it? Don’t do that.

My youngest is seventeen and in a few months, school of some sort (public, private, or home) will no longer be compulsory, so it feels pretty safe to say that in the end, none of my children chose to return to school.

But digging into these fears and understanding their roots meant that I spent the last bunch of years not stressed about the possibility.