Jeff Posey's Blog

January 12, 2017

What I Learned About Animal Time Solo Hiking 3,000 Miles

On the third day, seconds and minutes and hours are meaningless.

On the fifth day, now is the only moment, and time is marked by a soft droning hum like the subliminal base notes of a wide and deep river.

This is animal time, as distinct from human time as jet airliners are from the flight of birds, as lines of automobile traffic are from the march of ants, as the flicker of fluorescent lights from midday sunlight.

In animal time, when I stop for a break, the background drone reaches a relative crescendo in the absence of the staccato cadence of walking. When I look at the sun, I do not know if it is late morning, or noon, or early afternoon, and not knowing has no significance.

Jeff Posey at Penasco Blanco, Chaco Canyon National Historic Park. Photo by Jason Myers.

In animal time, there is no urgency beyond the physical movement required to find a good spot for the night or to return to base camp if I am day hiking without my full backpack.

Hunger comes of its own accord rather than by the artificial metronome of breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

The count of days loses clarity. Is it Thursday or Friday? Have I been out six days or seven? If I am to meet someone to pick me up at the exit trailhead, I go over and over the daily events to try and construct the number of days I have been out: When the dozing elk burst from a tangle of scrub oak as I approached, like a flushed covey of quail, a function of nature that threatens heart failure to a marauding human; the day two wolverines loped across a mountain meadow below me, gamboling like two misshapen golden retrievers; the first full day of my journey walking through a cathedral of white-barked aspen trees in the high angle of morning light when a tiny bird on a high-speed descent from the cliffs above nearly flew into my face, backpedaling in a frantic flutter of wings and a series of panic peeps, my eyes snapped shut in involuntary protective mode, the puffs and eddies of braking wing strokes cooling my sweaty face, and yet, even with such milestones, the number of days I have been walking—seeing and speaking not once to a human soul—is an unsolvable mystery.

Jeff Posey at Chaco Canyon National Historic Park. Photo by Jason Myers.

If my car is at the exit trailhead (always my preference), I cease to care. A day late or a day early to return does not matter.

Time, Einstein discovered, is relative, and while he meant that in relationship to speed, it also holds true to the mechanics of human time relative to the flow of animal time.

In nature, time is not a grid that defines or constrains or even compels behavior, but merely a dimension across which things change from one place or state to another.

In the absence of the metronome of a clock, time is an infinitely variable flow without momentum or resistance, without deadlines or artificial urgency, without any meaning whatsoever on the scale of seconds, minutes, and hours. There is only the relevancy of time in the macro: day and night, the progression of seasons, the changes of weather. In nature, the only time unit less than those larger macro times is measured in moments, with only the barest relation to the drone of now.

In static animal time, when you do not move through the world but remain still, time takes on a new flow, the slow progression of shadows across the landscape, the equally slow movement of stars and planets across the blue-black firmament in the absence of overhead sunlight, and the singular state of the moon, which moves to its own otherworldly cadence, a sundial of sorts across its face, the closest thing to a global timepiece of nature.

Jeff Posey approaching the summit of 14,065-foot Mount Humboldt in Southern Colorado. Photo by Jason Myers.

Returning to human time is difficult, a time lag the body resists, a grogginess that accompanies the loss of the temporary subhuman spirit cultivated during the long days of animal time, and getting back on schedule feels like a form of blasphemy against the rhythms of the real world, of real humanity, of real life.

Living on animal time makes me remember who and what I am, that my normal daily world is a mental construct that rides atop my human-animal body. Even when it fades beneath perception, I know that, given time, I can coax my animal self back into full-blown existence merely by walking a few days, a few dozen miles, alone in the wilderness.

I have solo hiked and backpacked more than 3,000 miles over a couple of decades, without timepiece or flashlight or weapon or campfire. People ask me, “Weren't you afraid?”

“Yes,” I say.

“Of wild animals?”

I shake my head. “Of people.”

I have been mortally terrified on my long walks only three times. The first was coming out of the white-columned cathedral of aspen I mention above, the trail crossing an exposed shoulder of rock, when I heard a zip and crack of a bullet, followed by drunken laughter. I crabbed backward and climbed up and around the shooters, never letting them know of my presence, never giving them a clear shot at me. “Hey!” I imagined them saying to each other, “See if you can hit that idiot walking out here all by himself!”

Another was after I crossed the spring-swollen Gila River, sitting beside the roaring water on a rock drying my reddened legs and feet in sunlight. Two men appeared suddenly behind me, having walked up the creek bank from behind. They looked like human animals, bedraggled and unkempt with low-tech hiking gear and boots made for working and not hiking, each with a rifle and holstered pistol. They regarded me like I imagined a predator might see me, nodded without a word, and continued slowly downstream, occasionally looking back as if keeping tabs on me. When they were out of sight, I skedaddled, quietly bushwhacking a mile off the main trail, careful to leave little evidence of my passing. I did not see them again.

And finally once near tree line hiking the continental divide trail in Southern Colorado when I caught a whiff of sweet pipe smoke. I stopped and turned a slow three-sixty, seeing nothing in the first two times, but then on the third I saw movement, a swish of the tail of a horse that had been led into a tumble of boulders among a tangled nest of Gambel oak. The hairs on the back of my neck prickled as I walked the open ground, imagining a pipe-smoking hunter watching me through his scope, hoping he did not succumb to a homicidal twitch of his trigger finger.

There were dozens, maybe hundreds, of other times I experienced lower-intensity terror not related to humans other than myself, but those are the stuff of other stories.

The Next Skywatcher by Jeff Posey at Upper South Colony Lake, elevation about 12,000 feet, below Crestone Needle, in Southern Colorado.

See Books by Jeff Posey at Hot Water Press.

The post What I Learned About Animal Time Solo Hiking 3,000 Miles appeared first on Jeff Posey.

August 30, 2016

Chaco Canyon Peñasco Blanco Trail: Double Anasazi Payoff

Peñasco Blanco is the westernmost Anasazi great house ruin in Chaco Canyon National Historic Park, New Mexico. I highly recommend experiencing the two big (and very different) payoffs of walking to Peñasco Blanco.

It’s hard to beat Wikipedia’s introductory description of the place:

Peñasco Blanco (“White Bluff” in Spanish) is a Chacoan Ancestral Puebloan great house and notable archaeological site located in Chaco Canyon, a canyon in San Juan County, New Mexico, United States. The pueblo consists of an arc-shaped room block, part of an oval enclosing a plaza and great kiva, along with two great kivas outside the great house. The pueblo was built atop the canyon’s southern rim to the northwest of the great houses in the main section of the canyon. The building was constructed in five distinct stages between AD 900 and 1125. A cliff painting (the “Supernova Pictograph”) nearby may record the sighting of a supernova on July 5, 1054 AD. —From Wikipedia

The Peñasco Blanco Trail leads you on an eight-mile round-trip hike that rewards you with two big payoffs, one obvious and well-signed, the other much more subtle.

This Post is Brought to You By

The Next Skywatcher by Jeff Posey

"You will never see the Anasazi the same way again."

If you like historical fiction, download your free ebook now

(No signup. No hassle. No price!)

Big Payoff #1: Peñasco Blanco's Infamous Supernova Pictograph

The infamous supernova pictograph is just across Chaco Wash at the base of West Mesa, at the top of which is Peñasco Blanco. A sign marks the spot, so it's hard to miss. If you cross Chaco Wash at the wrong place, though, you could miss it, and when it's dry, it can be tempting to just bull through the growth along the wash and cross where you wish. It's best to stay on the trail as best you can (it can be a little indistinct at times near the wash), and aim for the cliff overhang in the second photo below.

The red paint is surprising. All other rock art I've seen in the canyon is pecked, not painted.

It's not as high as I had imagined it would be, about twenty feet from the base of the cliff. With a tall home utility ladder, I could have touched it, although footing for the ladder would be dicey and touching such an iconic ancient artifact is a no-no. (And anyone who carried a twenty-foot ladder four miles across the Chaco Canyon floor would be...well, both strong and crazy.)

I've twice tried to get to this place, and each time a flooded Chaco Wash prevented me from getting to the supernova pictograph and Peñasco Blanco. But this time, the wash was dry and we crossed easily without getting our feet wet.

We saw dozens, hundreds maybe, of similar overhangs with flat or suitable surfaces on the bottom side. But we noticed no markings of any kind.

Why did the Chaco Anasazi choose this place? Why did they use red paint, when all other rock art in the park is pecked into desert varnish? Does this really depict the Crab Nebula Supernova of 1054, or is it of something else?

Like most things Anasazi, we will never know for sure. But we're modern humans, which means...we like to speculate and pretend that we know.

Strong circumstantial evidence points to the pictograph being a depiction of the 1054 supernova. The crescent is the Moon, the star shape to its left the supernova, and the hand (life-size) is taken to indicate that the site is sacred. Calculations of the Moon's orbit back to 5 July 1054 have shown that the moon was waning, just entering first quarter. These calculations also indicate that at dawn on 5 July 1054 in the American Southwest, the moon was within 3 degrees of the supernova, and its crescent oriented as on the pictograph (provided the pictograph is viewed looking up with one's back to the cliff, as the authors of the pictograph most likely did). With the apparent width of the moon being about half a degree, this pictograph comes basically as close as it possibly could to being a true scale rendition of the 1054 supernova seen in conjunction with the waning moon. —From "Solar Astronomy in the Prehistoric Southwest," High Altitude Observatory, by by P. Charbonneau, O.R. White, and T.J. Bogdan.

What I failed to see (and photograph) below the paintings was a faint image of concentric rings with flames erupting from one side. This photo shows it, though it's faint (bottom of the photo on the vertical face below the three red images):

Photo by Ron Lussier courtesy Astronomy Pomona.edu

On the nearly vertical cliff face below the supernova a Sun-symbol can be seen, painted in pale yellow over a much faded red background. This, combined with a clear view on the mesa top to an eastern horizon suitable for calendrical purposes, might well indicate that the site was also a solar-observing station. From there, the Peñasco Blanco Sun-priest perhaps first noticed the supernova prior to a sunrise observation. Given how rare such an event must have been, it is then conceivable that he might have wanted to record the event. —From "Solar Astronomy in the Prehistoric Southwest," High Altitude Observatory, by by P. Charbonneau, O.R. White, and T.J. Bogdan.

Here's a great field sketch of the Halley's comet portion of the pictograph by Peter Faris.

Field sketch of Halley's comet pictograph, Peñasco Blanco trail, Chaco Canyon, NM. Peter Faris, 1997.

I recommend The "Rock Art Blog" by Peter Faris, especially his post from 2010 titled "Halley's Comet Pictured in Chaco Canyon," where I found this sketch.

Note that everyone is not convinced this shows the Crab Nebula Supernova event of 1054. Richard L. Dieterle of the University of Minnesota believes it depicts a different alignment of celestial objects on another date that was only a few months before a flyby of Haley's Comet (and the Battle of Hastings in England).

June 21, 1066, when Morning Star aligns with the radial image, the moon aligns with the crescent, and the Pleiades align with the hand. —"Is the Chaco Canyon Rock Art a Star Map Showing SN 1054?" by Richard L. Dieterle on HotcakEncyclopedia.com (a collection of Winnebago history and legends).

Regardless of how you interpret this pictograph, combined with the second big payoff, this strongly suggests some really powerful people in the Chaco Anasazi world built and lived in the Peñasco Blanco complex.

(RELATED Author Note by Jeff Posey: "Mysteries of the Chimney Rock Anasazi Observatory")

Big Payoff #2: Skybox View of Downtown Chaco

The second big payoff is this grand view of "downtown" Chaco from the Peñasco Blanco ruin atop of the mesa above the supernova pictograph. You can see all the way from Pueblo Alto on the the left (north) to South Gap on the right, with the downtown complex in the center and Tsin Kletsin on the far horizon:

The ruins in the distance are hard to see at first. I didn't realize they were visible at all until I used my binoculars, and then I could pick them out with my naked eye. Under each red arrow are dark-brown structures that are the remnants of the Anasazi buildings (except for South Gap, which is a canyon, not a ruin).

A thousand years ago, these buildings would have been plastered with a sand mixture that gave them a buff-white color. They would have shone like moonbeams.

Can you imagine the power of the person or clan that commissioned Peñasco Blanco? They were like the rich family that buys the private box on the fifty yard line of the Super Bowl. Except, in addition to friends and relatives, they would have been accompanied by astronomers who watched and recorded (even if only in their memories) celestial events. And instead of football, they would have watched the comings and goings of participants in all kinds of ceremonies and special events.

From this vantage point, if you had good eyesight, you could see the processions of pilgrims arriving and departing through South Gap, and the lines of people marching from the north along the Great North Road to Pueblo Alto, and thence down into the canyon by way of the staircases cut into the cliff stone.

Given this impressive view and the supernova marking beneath it, Peñasco Blanco must have been a particularly powerful place.

Of all the sights I have seen in Chaco Canyon, this is the one that made the biggest impression on me. If you can walk eight miles through occasionally rugged territory, I highly recommend it.

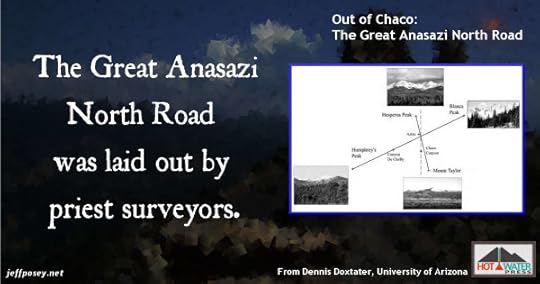

(RELATED Author Note by Jeff Posey: "Out of Chaco: The Great Anasazi North Road")

Peñasco Blanco: A Trail Guide

It's usually best to start with a map:

Courtesy National Park Service

The trail profile:

Courtesy Hiking & Walking

I hiked this trail with my buddy Jason Myers, and while it is only modestly difficult at times, it is eight miles round trip or more (especially if you thoroughly explore the Peñasco Blanco ruin) and takes four to six hours to fully enjoy. As the trail profile shows, the stretch from the Supernova Pictograph to Peñasco Blanco is the steepest and most rugged.

In the summer, when we did it, essentials are: sun hat, sunglasses, sunscreen, lots of water, a few trail snacks, and good boots. We both wore shorts, and that worked fine. Rain threatened the afternoon we were there, so it's a good idea to have a rain shell handy. Other than that, you will likely want binoculars and a camera.

Petroglyph Spur

A side-spur to the Peñasco Blanco trail that adds only a few steps to your journey takes you along a low cliff face that is sporadically covered with rock art.

Rabbits! More than I've ever seen before in the canyon. I kept watching for rattlesnakes thinking they would be feasting on them. But I didn't see or hear a single rattle.

Wait, the book says.... Jason kept looking at the book and then at the petroglyphs. "I can see them better in the book," he said. For many (most) of them, he's right. They can be rather faint, and many are easy to miss.

Sometimes Anasazi rock art looks like kids were just playing around. Why is it they could paint such wonderfully advanced images on their pottery, but their rock art so often looks as if it's made by a kid with Attention Deficit Disorder who didn't take their medicine?

There may be a genuine answer: Women did the pottery, while men tended to such important tasks as tapping rocks against cliffs.

What if a gifted Anasazi potter girl decided to try her hand at making cliff art? What if that is why the Supernova Pictograph is so much better? Is the red hand female?

Do you think the Anasazi saw themselves as lizards without tails? That's what many of their humanoid pictographs look like.

Or...what if the Anasazi themselves did not make these images? What if, say, the Navajo or Ute did, and they thought of the Anasazi as magical lizards? As usual, we will never really know because you can't precisely date rock art.

More lizard people. And one five-toed Bigfoot.

I get the impression that when one person started banging on a cliff to make these marks, everybody else around joined in, cramming as much as they could into one little area, and ignoring perfectly good similar places just feet away.

That's a pretty fine spiral there right of center. This panel looks more professionally done than some of the others. A more skilled rock-tapper must have done this one (a woman?).

In case you get turned around, the Park Service gives you a reminder.

Second Half of the Trail to Peñasco Blanco

Just when you begin to tire of childish Anasazi rock art, you look ahead and see the dark ruins of Peñasco Blanco on the horizon, though it's still quite a long walk to get to them.

The Peñasco Blanco ruin reveals itself high on West Mesa. Notice it's not just those dark piles to the right...they continue for quite a ways to the left, too, though they are just barely visible here.

After you cross Chaco Wash, you see the supernova petroglyph. And then the trail starts climbing....

Some bizarre rock foundations in the cliff below the ruins. The trail goes right up and through them.

Sometimes you do indeed need those rock cairns to show the way when the trail is hard to see.

In the middle of the day, the light reflecting from the light-colored stone is blinding (wear sunglasses and a good hat).

Even when you can see it really well looming above you, there is a lot of walking left to do. I got the impression they designed it this way, forcing you to look up at it for a long time before you actually get there. It builds anticipation, which increases the payoff of getting to it.

I knew Pueblo Alto lies due east on the horizon from Penasco Blanco, but we weren't yet high enough to see it.

The ruins of Penasco Blanco rise like a dark memory from the past.

A wide-angle view. It's surprisingly large and is hard to get a full appreciation of the layout and scale once you get closer than this.

See Jason in the doorway? He hid in the shadows like a lizard while I clambered around like a rabid coyote.

This remnant of a wall with a buttress hints at the fine stone work and strong architecture of the Anasazi.

Jason in the shade.

I kept looking at that doorway or window where he stood. You can see the intentional squaring-off at the bottom. But the top? It looks like the Hulk went blasting through there.

But there was no sign or scent of a big green man. "Smells like rock," said Jason.

Notice the stone work here. It's much more chaotic and haphazard than in other places.

What does that mean? Did the head of construction get sick, and his incompetent apprentice took over for a while? Or was a different clan in charge of building this section, and they didn't care as much about the design?

Ignore Jason's back. He's there only for scale, anyway (hey, something has to justify his existence).

What I really like about this photo is that it shows the curvature of the Peñasco Blanco structure. Unlike any other complex in Chaco Canyon, Peñasco Blanco is oval-shaped (see aerial photo toward the bottom of this post).

What that tells me is that this was a master-planned building. Somebody with the whole building design in mind was in charge.

Most of Peñasco Blanco is rubble. You can put your hands on the fallen building stones and feel the shaped faces and imagine the rough hands that worked them.

This also gives you an idea of what most Anasazi ruins look like: mounds of unorganized stone with a remnant spine that hasn't fallen over in a thousand years.

Look how impressively square these walls are. How they tie together. How straight they are. The courses of stones of different sizes.

This proves a very high degree of building skill. The master stone workers who built this section were at the top of their profession.

This long wall gives a hint of the majestic nature of what this looked like in its prime.

And these holes gave me long pause. I studied them from both sides. I have an impression than they were not intentional doorways or openings, but that someone had breached the wall by dismantling these little sections. A sign of warfare?

Violence certainly happened at Peñasco Blanco. There is compelling evidence of murder and mayhem, including cannibalism at the site. (See in particular Man Corn: Cannibalism and Violence in the Prehistoric American Southwest, by Christy G. Turner II, pages 95-111.)

Knowing of such extreme violence lends a somber air to the ruins, though, throughout most of its history, it must have been a relatively peaceful place, just as it is now.

(RELATED Author Notes by Jeff Posey: "Were the Anasazi Cannibals?" and "Were the Anasazi Nazis?")

If you like historical fiction,

Try The Next Skywatcher by Jeff Posey

"You will never see the Anasazi the same way again."

Download your free ebook now

(No email signup. No download hassle. No price!)

You can see two stories at least. When you reconstruct that in your mind across all the ancient foundations, you begin to feel overwhelmed by how large this place was.

There's another suspicious hole knocked into the wonderful Anasazi stone work. Could more recent pot-hunters have caused this kind of damage?

Look at the different stone style, from small stones of the same size along the layer with the hole, to alternating layers of large and small stones up top. Do you think they started building before the guys with the large stones arrived? Maybe they were delayed along the way...diverted to Pueblo Bonito, perhaps, by the big man in charge, or they stopped to harvest a seasonal explosion of rabbits.

This is where you get that spectacular view looking east toward "downtown" Chaco. I kept looking away from the nearby ruins and gazing into the distance, imagining that view when Chaco was at its peak.

At night, could you have seen the light of fires at each of those places? During the day, would plumes of smoke from cooking fires have marked the spots? Would the fields of crops along the canyon floor and even up on the mesa tops have stood out a darker green during the growing season?

Might the big man in charge of Peñasco Blanco have employed a few sharp-eyed boys to watch and notify him of anything worthy of seeing with his own eyes?

When it's time to go and you descend only a short distance, all of those "downtown" Chaco structures go out of sight.

But you're rewarding by this collection of broken pottery pieces, or sherds. This looks to me like a pile made by recent visitors. It's so tempting to take such a thing, but the guilt of responsibility rises hard in the chest, and even if you pick one up and put it into your pocket, most of them probably wind up back in this pile.

Even in this tiny sample of pottery pieces, you can see the skill of the artists. Why didn't they do more spectacular rock art? They were certainly capable.

Walk with care. The trail back can be treacherous.

On the way down, the canyon opens up. For quite a ways, no Anasazi sites are readily visible.

It's a long and sandy trail home.

Much of the trail is loose sand, like walking on a beach. Prepare yourself for that. It can be exhausting more quickly than you expect.

Casa Chiquita: Hidden Little House

The sign is clear, so you know when you've found it. But step back and eyeball back toward Peñasco Blanco, and the other direction toward Pueblo Bonito. You can see those places when you walk out into the canyon...but not when you stand close to Casa Chiquita's walls.

Who built this place? The Chaco Research Archive dates the Casa Chiquita site at A.D. 1100-1130, meaning it was built in one stage, one big effort over a single generation.

Did they have something to hide from the prying eyes of the big leaders at Peñasco Blanco or Pueblo Bonito?

Casa Chiquita has never been formally excavated. Any chance we would find evidence of the Chaco Canyon black market here? The place to go when you didn't want to be seen? Did visitors wear disguises? Was corn beer involved? How about pretty ladies?

As a historical novelist, I strongly suspect so. Human nature demands it.

Perhaps this was the headquarters of The Fat Man from The Next Skywatcher, or built in his honor. You know one of the fattest men in such a calorie-starved environment would be the guy in charge of selling vice.

End of Day Hike; Beginning of Daydream

This ends my trail guide. I highly recommend taking the time and calories to walk back a thousand years and be Anasazi in your mind for a few hours. It's great fun.

Jeff Posey at Peñasco Blanco, Chaco Canyon. Photo by Jason Myers.

This is how I spend most of my time at any Anasazi ruin—stare at things far longer than most other people. In my mind's eye, there are dozens of competing dramas going on, echoes from the past, or my own projections back onto the old ones. They ring in my ears like tinnitus. There are stories to tell.

At the end of the trail, there are scattered showers....

Fajada Butte in a summer rainstorm, Chaco Canyon National Historic Park. Photo by Jason Myers. Why is it crooked? I think he snapped it from the truck as we were driving back to camp.

"You will never see the Anasazi the same way again."

The Next Skywatcher by Jeff Posey

If you like historical fiction,

Download your free ebook now

(No email list to join. No confusing download instructions. No monetary price!)

More About Peñasco Blanco

Here's what it looks like from the air:

Courtesy Wikipedia

What did it look like when it was at its peak? Dennis R. Holloway, architect, did this digital reconstruction:

Reconstruction by Dennis R. Holloway Architect

Recommended Resources

For more information about Peñasco Blanco Trail, I highly recommend these sites:

Official Chaco Canyon National Historic Park Peñasco Blanco Trail page, so scanty it's just barely worth a page visit, but it's a good place to start.

Hiking & Walking, a wonderful collection of trail descriptions and photographs.

Wikipedia entry for Peñasco Blanco, a fair place to begin research on the ruin itself.

Slideshow by Rex Nye on YouTube, with a nice selection of photographs that scroll a little too fast for my tastes.

Chaco Research Archive entry for Peñasco Blanco, with lots of detailed information that gets pretty esoteric.

The "Rock Art Blog" by Peter Faris, especially his post from 2010 titled "Halley's Comet Pictured in Chaco Canyon."

The post Chaco Canyon Peñasco Blanco Trail: Double Anasazi Payoff appeared first on Jeff Posey.

December 3, 2015

Memoir of a Rookie Anasazi Potter

A few summers ago, I had the incredible experience of a three-day Anasazi pottery workshop taught by Gregory S. Wood, ArchæoCeramist, at Chimney Rock National Monument near Pagosa Springs, Colorado.

Wood is renowned for using only materials, tools, and techniques available to the local Anasazi at the time they fired their own pottery in the area. He further specializes in recreating the exterior painting styles. All of which together makes him the greatest living Anasazi potter.

I had never taken a pottery class or attempted working in clay other than the typical childhood obsessions with mud pies and unspectacular attempts at making adobe bricks for Cub Scout projects.

In fact, for this workshop, I really only wanted to watch and take notes.

Click on the cover to learn more.

Instead, as you’ll see, Greg and my buddy, Raymond, insisted I get my hands far too messy for note-taking.

That’s also a disclaimer: What I write here is from memory and memory alone (when external citations aren’t given). One should never trust the undocumented memory of a novelist. But I promise to try my best, with an aim more toward accuracy than precision.

When I searched for and signed up for this workshop, I knew I wanted to write a historical novel based on an extraordinary Anasazi potter. As I write this Author Note, I’m in the final editorial stages for Thirteen Spiral Stars, first book in The Last Skywatcher Triple Trilogy Series.

In the story, Sooveni, a young Anasazi potter in the year 1094, fires thirteen pots each with thirteen symbols of spiral shooting stars, with apparent magical properties. These pots, as you can imagine, cause enormous troubles for Old Tuwa, Master Skywatcher at the Twins, and Vingta and Uva who have to do all the dirty work of protecting everyone from the rampaging warriors of the High Priest in the sacred canyon—who, of course, wants the mystical pots for himself and his wives.

It’s a continuation of The Next Skywatcher, prequel to the The Last Skywatcher Triple Trilogy Series.

The first three books of the triple trilogy are historical thrillers with a hint of romance, the second trilogy will be murder mysteries, and the last three will be a subtle reflection of the first trilogy and reveal the true Last Skywatcher.

Modern Anasazi pottery camp

These shade tents were our home base for three days near the visitor’s center at Chimney Rock National Monument as we started the process of making Anasazi-style pottery from, literally, scratch.

The first morning, the workshop class of about twenty people followed Master Greg to a place where coarse clay had been exposed by erosion. He instructed us to scratch up a few pinches, spit in our hands, and see if we could work the resulting clay into tiny worm shapes. When you can make good wiggle worms from any dirt, it’s potential pottery clay.

In geological and soil-science terms, it needs to contain the right proportion of clay, sand (filler), and feldspar (a common but complex mixture of metal oxides that are the main vitrifying or fluxing agent of the ceramic). My first degree is in geology, so I can kind of geek out on this, but I’ll spare you.

Gregory S. Wood, modern master Anasazi potter

This is Master Greg demonstrating the basic tools of Anasazi pottery making: yucca-leaf paintbrushes, twigs for use like toothpicks, and smooth river stones for polishing away imperfections.

Other than fingers and fingernails, those are about all you need to work directly on the clay that becomes pottery.

Circle of influence on Anasazi pottery

Being an ArchæoCeramist, Greg likes to overthink things in the ways of both theoretical and practical master of the craft.

In other words, we think as much as we simply do and feel in his workshop.

This diagram by Greg shows the major influences on Anasazi pottery. It’s worth rewriting in outline form (helps me think about it).

Cultural versus Natural

I like the implication of the two big divisions. To the Anasazi, or any native ancient tribes or groups, their only direct clear and true outside influencers are natural forces external to them: Weather and food sources and rockslides and thunderstorms and animals and rivers. Each of these affected them greatly, yet none were animated by human spirits. So they must have their own, non-human origins of power.

The way they interpreted and understood the natural world of those non-human sources of power became their cultural world.

There must have been constant power interplay between what would appear to some as merely the physics of the universe and to others as intentional acts of the gods.

There would be those who believed the sun would come up the next day only if they performed the necessary daily rituals, and others who knew it would come up anyway.

Cultural

Soul

Society

Craft

Art

Fire

Technology

Fuels

Kilns

Natural

Earth

Geology

Clay

Temper

Water

Environment

Mountains

Desert

The primary technologies of making Anasazi pottery were the fuels they could use to reach temperatures hot enough to fire clay, and the kilns they built to concentrate and retain that heat.

In the Chimney Rock area, the choices of fuel are: juniper, piñon, Ponderosa pine limbs, scrubby Gambel oak, alder and cottonwood if you’re willing to follow a stream long enough to collect a load, other shrubs such as rabbitbrush and mountain mahogany, and any remnants of agriculture, such as corn cobs.

Expert potters know which types of fuel burn hottest and longest, or start the firing process most efficiently for their circumstances.

In our fire, most fuel came from juniper with about a third oak, and less than 10 percent from other scrap wood easily at hand.

The technology of the kiln is what would take the most practice, experimenting, and skill apart from shaping and painting the pots themselves. Almost anyone could gather wood. But to build a trench kiln and manage the firing took great skill.

But I get ahead of myself. In the workshop itself, after we gathered a few samples of local clay, we actually worked material Greg brought with him. I believe he said he had collected it in the vicinity of Mesa Verde National Park, eighty miles to the west.

Only a deranged Anasazi potter would haul clay that far back in their day. Not that it didn’t happen. It could have. A deranged potter could be very entertaining in a good novel.

Grinding clay the Anasazi way

Grinding clay is tedious. It doesn’t go quickly. There’s not really much technique involved. It’s just rocking and dragging a grinding stone over hard fragments of clay, pulverizing them into powder.

I can imagine an Anasazi potter spending days, weeks, maybe the first half of each moon cycle just grinding clay into a consistency that would make good pots.

A lump of wet clay

Add a little water, and you’ve got a lump of clay. Anyone who made mud pies as a child will know the feeling.

Potters, I learned, add water not so much by formula as by feel. Add a little water, and mash it up with the clay. If it’s too dry, add more water. If it’s too wet, let it sit a while and dry off. (We were above 7,000 feet elevation in the summer, and the humidity was very low, in spite of some afternoon sprinkles. We constantly battled clay that dried faster than we could work it.)

Making a thin layer of clay

Most of the workshop class chose to attempt mugs, and I followed their majority lead. As I said, I’ve never worked clay in my life.

First, Master Greg said, mash out a layer of clay to make the base of the mug. It had to be thin, but not too thin (try getting a master potter to explain that to you—I just showed him and he shook his head: “Thinner.”)

So, of course, I made mine too thin and had to start over again.

A vessel bottom cut to shape

Using my best freehand skill of dragging a toothpick-like pine splinter in a perfect circle, I boldly cut out the base of my mug on a small, flat working stone. Not bad, except for that little pointy pooch on the right.

What’s next? I had to ask because by now, everyone else was way ahead of me.

Scoring the vessel base

This time I cheated and used a modern toothpick to make scores around the edges of my mug. These help the first row of clay that becomes the side of the cup stick firmly to the bottom.

Rolling out the clay

Remember the tiny wiggle-worm dirt I mentioned in the opening? This is the same thing, but at snake-size scale.

This part of the assignment: Roll out a consistently textured and sized log about double thumb thickness.

Making clay rings to stack into vessels

And then you make a bagel or donut shape by connecting the ends of that snake of clay.

I’m worried mine are too skinny at this point. I have no idea what I’m doing. I’m just watching and following along.

Of course, I end up having to start over and make a thicker ring. At this rate, everyone else will be firing their pots while I’m still working with mud.

Rookie Anasazi potter at work

After I scored the bottom of my first bagel and mashed it onto the base, I ran my hands round and round, squeezing and shaping to make the bottom sides of the cup.

Going around and around like this, dipping your fingers into mud (it started as clear water for dipping, but soon turned into soupy mud) to keep it wet and workable, you feel and gently work the whole piece into the right shape and thickness.

Stacking rings of clay to make a vessel

Another bagel of clay makes the second tier of the mug sides.

Being so bad at it, I could appreciate the skill of those who could shape symmetrical, smooth, wonderful little bowls and mugs. I felt more like a kid making a mess.

Anasazi Jeff potter hands

This is why I have no notes from that day.

For a word guy like me, it felt like being in handcuffs.

Getting a handle on it

See how thick my mug is? And how variable the thickness and irregular the container? That is a sure sign you’re not seeing a master potter at work.

But look at my handle! I’m proud of that. I mean, it really looks like a mug handle!

I got lucky. And then kind of mashed it out of shape trying to get it to stick to the body of my mug because I’d let the surface of the clay dry too much.

Sigh…this is not easy.

I can already see that only masters of the craft could do it well and keep the process going at the right pace to end up with a quality product.

Applying the slip coat

To the raw or main body of the pot, we covered it with a soupy mixture of extra-fine clay called “slip,” because it kind of slips right over it, fires to a glaze, and gives you a much better base for applying the final artistic layer of paint.

Drying the slip coat

Did every Anasazi potter do this? Apply the slip, and then walk around with their hand in the pot or mug while it dried enough to be able to set it down without sticking to anything?

My arm got tired. A fly discovered I was vulnerable and enjoyed terrorizing my left side. Everybody else already had theirs sitting and drying while I walked around like a mute ventriloquist with a mug-shaped puppet.

The old Anasazi potters would have laughed at me. I would have been valuable to them only for entertainment. Maybe they would have given me scraps of food to teach their children how not to make pots.

The Master burnishing a dried pot

When you’ve applied slip the right way and let it dry, you get a milky, even color like Master Greg shows here. In this photo, he’s demonstrating how to “burnish” it with a river-polished stone.

Burnishing smooths and evens out where the slip has clumps or drip marks.

To get mine to look this smooth would take months of burnishing. Maybe years.

Anasazi Lunch!

Yay, lunch!

Everyone knows Anasazi potters’ preferred foods are Kalamata olives, bean sprouts, and humus. And pita bread, not shown (you know how it can be shy sometimes).

So that’s what I had for lunch.

Making a yucca-leaf paintbrush

While our pots are air drying, it’s time to make paintbrushes. From dried yucca leaves, we stripped away long pieces of fiber, splitting them into several thicknesses.

Then we soaked the ends in water while we burnished the slip-covered pots and mugs, and then used this tool—an elk horn cut and polished smooth from use—to mash the soaked ends of the yucca to make them pliable enough to use as tiny paintbrushes.

Testing a new yucca-leaf paint brush

When they’re ready, you have a long, limp piece on the end like this, and then you can cut it to make a stiff brush, or to ensure the ends aren’t ragged.

Anasazi black paint source: Rocky Mountain Bee Plant

We did not gather the plants and make our own Anasazi ink from the Rocky Mountain Bee Plant.

Cleome serrulata Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Cleome serrulata Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

It’s a beautiful plant that can become a wide bush as tall as a person under the right conditions.

Because it takes so long, Greg harvested and boiled the whole plant down to a paste that became genuine Anasazi paint.

When it’s first applied, it has a deep purple color, but after it’s fired, it’s charcoal black.

An Anasazi paint pot

With a few drops of water and some dried Bee Plant paint, Master Greg mixes it in what would have been a highly valued paint pot hollowed into a flat river stone.

When a potter moved, this is something they would likely have deemed worth the effort of carrying.

The master’s steady hand

Master Greg demonstrates the careful and tedious application of paint using a thin yucca paintbrush to make genuine-style Anasazi patterns.

Mistakes are hard to fix and essentially cannot be tolerated. You have to be like jazz guitar legend B.B. King, who I heard once say in a radio interview that he never made what he considered mistakes because he would repeat the “mistake” and incorporate it into the design of his music.

Anasazi pot painters had to have a philosophy much like that.

Basic tools of the Anasazi potter

I mentioned these before, but here they are in close-up, the basic tools for working and preparing a pot.

There is a smooth burnishing stone, a thin stick for scraping and poking, and straw-like yucca paintbrushes. I flagged my paintbrushes with tabs of masking tape to make them easier to find when they blow away, which they’ll do in the lightest of wind.

Toolkit of the Anasazi Master Potter

These images are of Master Greg’s Anasazi potter toolkit, a mishmash of modern and ancient goods. The modern materials are mostly for teaching, and the ancient materials are what he uses for making pots.

I won’t even attempt to list all that’s here, but I will point out the scrapers made of dried gourd in the bottom image, slightly right of center. These are used to scrape out the inside of bigger pots or ollas. We didn’t use them for mere mugs.

Anasazi Jeff’s pottery workbench

This was my open-air pot-painter’s workshop. Greg instructed us to find a place where we could work quietly while painting our mugs, and I wanted to be away from the group and take my time.

View of Chimney Rock from my workbench

As you can see, I faced the columns of Chimney Rock from where I sat painting my mug. When I squinted and ignored the sound of modern humans nearby, I felt like an Anasazi. Sort of.

Anasazi Jeff’s beginner potter’s painting style

I decided to make my own design rather than attempting to recreate genuine Anasazi styles.

As usual, I had no idea what I was doing. I overheard others refer to this as “those not-smiley faces.”

I didn’t explain myself, but I wanted my own rendition of Másaw, traditional god of the underworld, caves and dark places, from the legends of Anasazi descendant cultures and the Maya.

Másaw is described as having slits for eyes and mouth, no nose, and has a flayed head—meaning it’s been skinned. Not pleasant, I know.

If it offends you, look away.

Superior craftsmanship of the Master’s Anasazi pottery

Compared to mine, this mug and its painted design is a work of genius. Which, of course, it is, being by Master Greg.

Mine, on the other hand, is the work of a beginner. I’m not ashamed in the least. But I do recognize the stark differences in quality between the work of a master and the work of a first-timer.

True Anasazi pottery shards

A fragment of genuine Anasazi pottery with an enduring design, a tentacle curling into a spiral.

After painting my own mug, it’s easy to see and imagine the individual strokes of the painter.

This fragment is much whiter in background (better slip?) and the paint is much darker (better paint?).

The interlocking spiral design reminds me of a neural synapse, where biological nerve cells come together but don’t quite touch, and neurotransmitters must diffuse across the boundary.

The Anasazi likely would not have made that connection.

I wonder what this meant to them?

The pit of the first fire

The firing of Anasazi pots is as painstaking a process as creating the pots to be fired.

First, a small trench or pit is dug, measured here to accommodate a cross-log to be used in the second firing.

The first firing is simply like a campfire in a pit lined with stones to create a deep bed of coals.

Fire pit at Chimney Rock

This is the pit-kiln location below Chimney Rock. A thousand years ago, this scene might have looked much the same. Without the white bucket, of course.

Drying the “green” pots

While the fire burns into a bed of coals that Master Greg says needs to be six- to eight-inches deep and not smoking, we further dry the pots sitting on small flagstones that will be used as “furniture” in the kiln.

Furniture is the flagstones that will be placed directly onto the coals with the green pots set on top without touching the smoldering wood below.

Preparing the bed of coals

This is Master Greg placing the flagstones onto the coals to be the furniture that supports the pots.

Notice his thick gloves. The Anasazi would not have had such a thing. It’s a hot job. That fire is radiating heat at a very high temperature. But you have to work fast. When the coal bed is ready, it’s ready.

The Master placing the first pot to be fired

Master Greg places the first pot.

No pot or mug can touch the coals or other pots or mugs.

Protecting the pots with pieces of old pottery

After all the pottery to be fired is stacked onto the furniture, they are carefully covered with large, old pottery shards.

Another fire, as you’ll see, will be built over the top of these pots, and the shards protect the new pots from collapsing firewood.

Again, I can appreciate how much goes into doing this correctly, and how much labor is involved in working directly over a very hot fire. Timing is still crucial.

The lower bed of coals must still be burning very hot when the second fire is built over it.

Old pottery shards over new pots

This how the pit-kiln looks prior to stacking wood over it for the second fire.

The Master honoring the spirit of the pottery

In honor of the ancient spirits of both the place and the activity of making pots like the Anasazi, Master Greg waves an owl wing over the pit, still emanating extreme heat.

A small pile of corncobs will be incorporated into the second fire to honor the spirits of the grain that sustained the Anasazi.

The center pole of the second fire

This is the center structural pole that will hold up the overburden of firewood for the second firing and protect the pots below. My buddy Raymond is helping Master Greg.

Structure of the second fire

This is the structure of sticks and wood for the second fire, carefully engineering to prevent sudden collapse onto the pots below.

The second fire is ready to light

Adorned with sacred corncobs and strips of piñon wood and tufts of grass, the second fire is ready to be lit.

The second fire is lit at Chimney Rock

The first rush of flames from the second fire. The wood is dry and hot from the layer of coals from the first fire below the furniture on which the pots being fired sit.

This must look much as it would have a thousand years ago in Anasazi time at Chimney Rock.

Anasazi Jeff’s and Raymond’s hot new mugs

Jumping ahead to the dramatic end, this is me (left) and my buddy Raymond (right) holding our mugs still scalding hot out of the fire.

We were too busy to take photos while we uncovered the pots and extracted them from the fire.

The sounds were interesting. Occasionally there would be a loud crack, and Master Greg would say, “Something blew.” He meant a piece of pottery had too much water in the interior of the clay and it exploded.

Both mine and Raymond’s mugs had such pockets of too-moist clay and parts were blown out. My lovely handle lost some of the bottom part.

But I’m still proud of it. It’s my one and only Anasazi mug made entirely by my own non-Anasazi hands.

This is my mug today (with local native sand lovegrass in the background).

This is my mug today (with local native sand lovegrass in the background).

The color of the paint before we fired it was much richer, dark purple and glistening. Firing makes it fade. But I still like my mug. It’s one of those things I’ll keep and treasure forever.

Anasazi Jeff with the Twins at Chimney Rock

I carry that damned leather journal everywhere I go. People think I’m a Bible-toter. But my good book is the hundreds of notebooks I’ve filled in my lifetime. When my hands aren’t too dirty from making pots, that is.

This perspective of Chimney Rock, my Twins in the stories I write, is what was so special to the Anasazi skywatcher. Every 18.6 years, the full moon rises for a few months precisely between these two columns.

Near where I am standing would have been the skywatcher’s platform, or observatory, and they would have noticed and recorded in some way the slow progression of the moon and wandering stars (planets) and longhair stars (comets) against the unchanging background of fixed stars.

In the sky to the upper right would have been the location of the Supernova of 1054, the Crab Nebula exploding into a light so bright it was visible during the day for a month, and at night for a couple years—recorded by Chinese and Mesopotamian scholars and skywatchers.

All of that must have seemed like magic to the Anasazi.

Just as potters who could make perfect pots and mugs might have been regarded as purveyors of a sort of magic.

And so ends this workshop of trying to make pots like the Anasazi. If you get the chance, I highly recommend the classes by Gregory S. Wood, ArchæoCeramist, at Chimney Rock National Monument near Pagosa Springs, Colorado.

The post Memoir of a Rookie Anasazi Potter appeared first on Jeff Posey.

October 30, 2015

Pagosa 2015 Snapshots and Notes

Ah, Pagosa Springs, Colorado. I’ve been in love with this place since driving through with my parents on a family vacation in high school. At first, the attraction was cool mountains, lush forests, noisy streams, and thousands of miles of some of the best hiking trails in North America.

I’ve visited more than a hundred times since. I’ve solo backpacked more than 2,000 trail miles in nearby wilderness, and I’ve hiked another 500 or more with other people.

Now when I return to Pagosa, I see it through the foggy lens of time. A thousand years ago, this was the farthest northeast corner of the Anasazi Empire.

Twenty miles due east of Pagosa is Chimney Rock National Monument, home base of my historical novels about master skywatcher Tuwa and his astronomical observatory using a complex circle of stones and a record of events in knots and fringe in a long string record.

The mother hot spring of what is now Pagosa Springs must have been an active place (Pah-go-sah is a Ute word for “hot water”) a thousand years ago. The Anasazi outpost at Chimney Rock had line-of-sight communication with Chaco Canyon (via signal bonfires on Huerfano Mesa and Pueblo Alto), and the stone construction there is unmistakably of Chaco Canyon style.

The hot springs, a long day’s walk due east of the Twins (my historical fictional name for the dual spires of Chimney Rock), would have been a natural gathering place. Farmers from the foothills of the South San Juan Mountains—likely insulated from the rule of any High Priest in Chaco Canyon—would have known of it, bathed in its sulfur water, plastered themselves with its mineral mud.

New arrivals, ancestors of the Utes and their mountain-dwelling offshoots, would have come down to trade and take the waters.

And, of course, the elite of Chimney Rock, the master skywatcher and his monk-like acolytes and their wives and husbands would likely have made forays to the hot springs.

Pagosa Springs back in the day of the Anasazi would have been a Wild West town on the fringe between the hard-fisted rule of Chaco Canyon and surrounding wild tribes and clans.

When I tour Anasaziland, mostly desert and dry plateaus and canyonlands to the south and west, I’m struck by how foreign and different the Anasazi outpost of Chimney Rock must have been. Did emissaries of the High Priest in Chaco Canyon lobby to be assigned there? If not, what was wrong with them?

I’m not much of a photographer. I tend to get lost in moments and forget to snap the shot. I also use only a phone for pictures because I like to carry as little as possible. My buddy Mike supplements my photo collection here. He uses a real camera.

These are from my 2015 trips. I’ll add more from time to time as I dig through the digital brain of my phone from our trip in June. And I’ll add photos by others as they come in.

River, Marsh, Spring, and Ridge

The San Juan River flows like an overgrown mountain stream through Pagosa Springs and then runs west to the Four Corners area, where it turns southwest and ultimately joins the Colorado River that (sometimes) flows into the Gulf of California (also known as the Sea of Cortez) after cutting through the Grand Canyon.

San Juan River

Looking north on the San Juan River toward Pagosa Peak (highest on the left) and the Weminuche Wilderness.

When I hike back into that area, it feels like I’m returning home. I’ve made at least fifty backpacking trips into those mountains, and more than double that many day hikes.

I’m a glutton for the punishment of hard wilderness walking, though five knee surgeries have slowed me down. My two-week-long, 100-plus-mile hikes are over.

I sure love looking up into that area from the river, though. I’ve been all up and down the Rocky Mountain spine from New Mexico to Montana. I’ve found places as pretty and appealing. But nothing more pretty and appealing than the San Juan Mountains of southern Colorado.

Why go anywhere else? Even in my mind, when I’m dreaming up my novels, my characters always end up somewhere in or around Pagosa Springs.

Warm River Marsh

Like pearls strung alongside the San Juan River downstream of the Mother Hot Spring in Pagosa Springs, a series of ponds begin with this one.

Faint steam rises in tendrils from the water, warm to the touch. As you walk along the concrete pathway, part of the town of Pagosa Springs River Walk, the downstream ponds cool until a finger plunged into the water detects no warmth at all and no steam tendrils rise from the surface.

Imagine the way this would stand out in winter, a haven for wildlife seeking warmth. In October, when I took this photo, a ring of green surrounded this pond, but the cooler ones to the west were already brown, giving in early to coming winter. A chorus of redwing blackbirds sang from the cattails, and the slip-trails of muskrat crisscrossed the marsh grass.

It’s a magical place.

The Ridge from the Marsh

From the river and its marshes rises this ridge of fractured shale. The river bends away to the left, eroding this black cliff. The warm marsh is also to the left.

From the top of this ridge, the view of downtown Pagosa Springs, the river, and the mountains to the north and east is spectacular.

In my mind it’s a place of drama. Because it overlooks….

The Mother Hot Spring

This is a shot (by Mike) from the ridge looking east. Just to the right of that fancy brown-topped building is the mother hot spring. The warm marshes and river are down and to the right.

Close-up of the modern Mother Hot Spring

This is what the mother hot spring at Pagosa Springs now looks like. In the old days, it was muddy marsh all around, hard to get to.

Now it’s easy to stare into the bubbly depths of what is advertised as the deepest hot springs in the world.

I like to stand on this ridge

This is the top of the ridge as it slopes west. This photo is facing the same direction as the earlier one that looks down on the mother hot spring.

That’s me at the top looking down the steep meadow that leads up to the cliff edge (just behind me).

Danielle and Vicki tuckered out before they got to the top and had to take a rest. I’ve never understood flatland lungs. I’ve always been able to go like a steam engine, thin air be damned.

But look at this place. Peeking over the ridge along which I’m standing you can see the mother hot spring and the flatland around it. That’s a powerful place to be if you want to spy on people down there.

I’ve got some imaginary drama planned for this place in The Last Skywatcher Series.

Reservoir Hill

The Pagosa Springs River Walk connects to a large town park called Reservoir Hill (as far as I can tell, it’s named that because they put a big water tank for town water up on the hill—I suppose I should give town leaders credit for not naming it Tank Hill), with miles of hiking and mountain bike trails, a meadow with a pavilion for concerts and outdoor gatherings, and a disc golf course that always seems to have at least a few people playing in good weather.

You can see it as the forested hill rising behind the mother hot spring in the photo taken from the ridge.

Cougar Bench of Pagosa Springs

This carved bench, by artist Chad Haspels, is always a pleasant surprise.

Here’s a close-up in rather poor lighting.

The bench and carving has been recently restored, with a new coast of varnish applied. I’m glad they did that. It was getting rather worn and faded.

More here: Artwork Refurbished on PagosaSprings.com.

I wonder what artwork in wood the Anasazi and their contemporaries made in this area. Every culture, given wood and tools harder than wood (stone), has made carvings of their world. They certainly would have been familiar with the cougars (a.k.a. mountain lion and puma) in the area, some of the largest in the state.

The ancient ones would have appreciated this bench and its art.

Pagosa Peak from Reservoir Hill

From the top of Reservoir Hill is this panorama looking north to the cluster of mountains around the Fourmile Creek drainage, Pagosa Peak (12,640’) prominently to the left. I’ve climbed it twice. Failed on one other attempt.

On yet another venture, I climbed around it above tree line to get a line-of-sight to Chimney Rock National Monument (the Twins in my historical fiction parlance). I wanted to test whether a scene I’d already written could actually happen: Would a bonfire on the southwestern slops of Pagosa Peak above tree line be visible from the Twins? Yes, absolutely.

I sat for more than an hour imagining how a group of adolescent boys would do such a thing to surprise their grandfather skywatcher back at the Twins. If it didn’t happen, I would be surprised. In my fictional world, it definitely did.

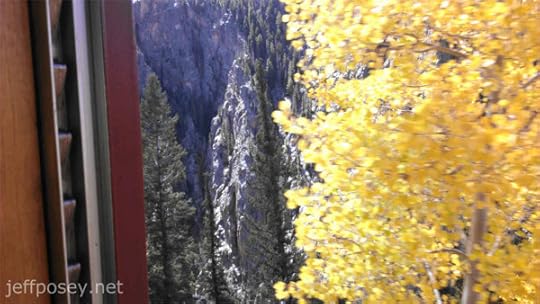

Cumbres & Toltec Scenic Railroad

The name of this railway is mystifying. Toltec? Really? They were a culture more or less contemporaneous with the Anasazi, but centered 2,500 miles to the south near Mexico City. It’s highly unlikely that any true Toltec ever walked the line that became this railway.

We rode it at the perfect time to see spectacular fall foliage color, the first week of October.

Beginning of the Line

The steam engine of the Cumbres & Toltec Scenic Railroad sits ready to haul a long string of cars up the narrow-gauge line over a high pass between Antonito, Colorado, and Chama, New Mexico.

There’s a competing narrow-gauge railway (narrow to better navigate the tight twists and loops and turns necessary to find a grade up and down which a steam engine can haul people and lumber and minerals) that runs from Durango to Silverton, the Durango & Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad Museum (yes, it’s a museum on iron wheels and rails).

I’ve ridden both, and given a choice, I’d take the Cumbres & Toltec line, though by a bare margin. When in doubt, take both!

My lovely wife Danielle and I are ready for the ride!

(No, I’ve never been to Alaska, despite the advertisement on my cap. My mother took an Alaska cruise this summer. She got to see glaciers and whales. I got the hat.)

Sagebrush Plains and Train

Before we climb into the mountains and spot our first fall foliage, the train loops through a high plateau of sagebrush as it gains elevation.

Top speed on the train is in the neighborhood of fifteen miles per hour. And the loops are so wide and get so close to each other at the necks of the loops, it’s often tempting to jump off the train, hike up a few dozen yards to the higher track, and wait for the slow train to come along again.

But I didn’t do that. The seats are comfortable. The clacking and swaying of the train is mesmerizing. I feel for the Anasazi who never had a chance to experience such a thing.

Color in Hiding

Ah, the first plume of hidden color among the evergreens.

Tufts of Color

And we begin to see more, with hints of reddish colors.

Blur of Fall Foliage

An aspen in full color close to the train seems to zoom by in a blur of bright yellow.

But we’re the ones “zooming” along at fifteen miles per hour.

Out the Train Window

After that flash-blur of color, you begin to pay more attention and look ahead to find scenes like this.

Fiery Red!

It almost looks like a smokeless forest fire.

Hoodoo and Fall Colors

Beyond the hoodoo standing guard beside the tracks is a deep valley braced by mountains covered in fall color.

This is the kind of view that makes your eyes go dry because you don’t want to blink and miss even a microsecond of gorgeousness.

Train Hanging Over Valley

Don’t look down. Look out. The deciduous trees are completely segregated by color.

Vista of Color

Again, without the train.

Man, what a view.

Waves of Mountain Color

They’re like giant frozen waves of rocks and trees with shocks of yellow and orange.

Cliff and Train

It’s not all color, even at peak times in the fall. Sometimes it’s cliffs, which oblige viewers at any time of year.

Noe the people hanging out the window. The back of my head is probably in hundreds of photos from people in cars father back.

This is a classic shot along this railway.

End of the Line

Finally, back in Chama, New Mexico, the engine gets to take a rest in the afternoon sun.

I’ve no photos, but the rail yard works, with all the mechanical maintenance and repair buildings and barns, is as fascinating as the train itself. The people who keep these relics running are smart, hard workers. (And they’re all covered in soot and grime—offer to shake the hand of any of them, and they back away with their hands up. “You’ll never get it off you,” I overheard one of them say.)

Piedra River Canyon Day Hike

Piedra River Trail Head

If you are ever in or around Pagosa Springs, Colorado, this is the best short day hiking trail around, according to me and my wife, Danielle.

Why? Short walk, a shade over two miles round trip (though you can go much farther if you want). Grade is easy. Trail is clear. And you cut through a wonderful little canyon.

Read more about it on TripAdvisor.

Meadow of Piedra River Trail

Your walk begins in a tilted meadow with the river (a big mountain stream, really) to the left.

A faint trail soon splits off to the right, up to some cracks in the rocks that have ice in them year-round. If you need more exercise, that’s not a bad side-trip.

Down the Canyon

This is your first good view looking down the canyon. The stream rushes, the sun is warm, and river otters are said to ply the waters (I’ve never laid eyes on one).

Cliff Across the Way

I like this photo. The cliffs across the Piedra River from the trail, before you get down into the depths of the canyon.

Always walk slowly and look around a lot. Seeing is high-quality living.

Canyon of the Piedra River

This is the big payoff view of the Piedra River Canyon.

It’s not the only payoff view. There are hundreds more. Heck, every step gives you a slight variation on yet another payoff view.

The first time we walked this, we both kept saying, “Wow.”

It’s easy to see why the big blocks fall, with the river eroding them from the base like this.

The last time we were there in the spring of 2015, the water was maybe three feet higher. That adds a lot of background noise, let me tell you.

Dark Cliff of the Piedra River

Not a good photo, I know. Bad lighting. But it’s the most massive cliff profile you see on this walk.

From the road, there’s a short trail from a pull off that leads to the top of this cliff, so you’ll sometimes see people up there looking down on you.

When I see human figures up there, I set up for a picture and call up to them, “Step a little closer!”

Sometimes they do.

“Just a little closer!”

When they bite and come closer, I switch to video hoping to catch some visual drama.

(Note: I’m kidding, I’m kidding. I’d never do such a thing. Especially with my wife around.)

Girls Looking for Pretty Stones

Below that dark looming cliff, there’s a wonderful little sitting area beside the river. When you look down at the beach and into the cold, clear shallow water, there are countless colorful pebbles and stones.

Danielle and Vicki began picking out their favorites and setting them out to dry.

Warning: Be prepared to carry out a few more pounds than you carried in. Little blue and reddish pebbles still hide in the nooks and crannies of our car and fanny packs. We’ll never get them all back out again. We always travel with the tiny souvenirs of the Piedra River Canyon.

Cliff over wife and friends

Cliffs on the way out with Danielle, Vicki, and Mike for scale.

Would you climb those cliffs?

Me either, but people do. Climbing pitons for tying off the ropes of climbers cover this and other cliff faces. You’ll often see climbers making their way up, a partner on belay below, and an inevitable nervous dog or two looking up at their insane masters.

Cliff over Mike

More towering cliff, with Mike for scale.

Cliff over Danielle and Vicki

A typical view walking out, with Danielle and Vicki for scale.

Big blocks of the canyon wall have fallen over time toward the riverbed, and the trail winds in and out of them. It’s a magical place.

Cliff over Jeff

Now it’s my turn. When I take pictures, I’m never in them. I have to rely on the cameras of others to get a glimpse of me. Thanks, Mike!

Big Tree

That’s one big tree that dwarfs Vicki and Danielle. Look how it’s growing from that boulder. So, the boulder obviously has not shifted in the what, hundred-plus years it’s taken for this tree to grow?

I’ve spent the equivalent of years in deep back-country wilderness. It’s my experience that, while most people think the wilderness is a “wild” and active place, most of the time, very little happens. Bounders fall and sit the way they landed for hundreds of years.

And then another boulder falls.

My father, a World War II B-17 Flying Fortress veteran, says flying, even in war, is boring most of the time because nothing happens but getting there or getting back. But then there are the long moments of sheer terror.

When this big boulder finally rolls, will this tree feel the terror?

Treasure Falls Trail

This is one of the shortest hikes in the area, on the main highway (160) about halfway between Pagosa Springs and Wolf Creek Pass.

But the payoff is a wonderful waterfall.

Treasure Falls Sign

Note the “no restrooms.” There used to be one here, but they took it out, I don’t know why. It’s also so heavily used, it’s hard to find a private place to do your business. So it’s best to start this walk with an empty bladder.

Treasure Falls

This is not at the Piedra River Canyon, which is west of Pagosa Springs.

This is Treasure Falls, just off Highway 160 between Pagosa and Wolf Creek Pass, which crosses the continental divide.

A couple of years ago I solo hiked up and over Treasure Mountain from near these falls in a soaking rain. People think I’m crazy. But I loved it.

At the top, wet and bedraggled, an eagle flew low over me clutching a small animal, mouse or vole or chipmunk, and careened into the trees. I moved sideways and kept my binoculars on the spot and finally found the mass of sticks that must have been the nest.

No one else in the world saw that. Just me.

Have I mentioned how much I love hiking in deep wilderness? Moments like these stay with me forever. I have thousands of them, so many I’ve forgotten most. But they come back to me when I need them.

Treasure Falls from Afar

It’s just plain pretty no matter how you look at it.

Pagosa Lodging

We’ve rented more than a dozen homes through VRBO (Vacation Rentals By Owner). This is our favorite.

The Lewis Street Treehouse

This is the most comfortable place we’ve stayed in and around Pagosa Springs. Find out more on the VRBO listing.

See my review here: Our Favorite Pagosa Springs Rental! Mine shows as “Anonymous” for some reason. It’s signed —Jeff & Danielle. So it’s not really anonymous at all. The VRBO system seems to think I want to hide my identity.

Rainbows

I’ve seen more rainbows in and around Pagosa Springs than anywhere else. They must have a good contract with whoever controls the weather.

Rainbow from the Treehouse

From the front deck of the Lewis Street Treehouse. It’s a double rainbow, though you can’t see the double in the photo.

So Long!

Goodbye from Danielle & Jeff

If you ever visit Pagosa Springs, Colorado, I hope you enjoy it as much as we do!

The post Pagosa 2015 Snapshots and Notes appeared first on Jeff Posey.

September 8, 2015

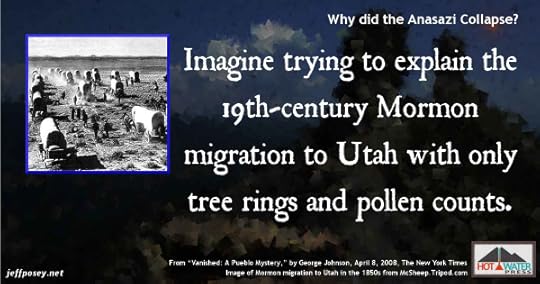

Why Did the Anasazi Collapse?

This is the single most enduring question about the Anasazi culture. Why did they abandon the Four Corners of the American Southwest by about A.D. 1300?

There are several competing and commingling theories about what drove (or attracted) them away. Drought, or climate change, is the most commonly believed cause of the Anasazi collapse. But recent ideas include extremist politics and religion, and an unsustainable stratification between the rich and poor—the ancient equivalent of income inequality that so infuriated the masses, they couldn’t take it anymore and left.

Climate change and drought is easy to understand. If your farmers can no longer grow enough food to feed your own people, and the drought lasts longer than the food stores you have set aside, then your culture collapses. The game is over. Those who can move, do. Those who can’t, perish.

Indeed, the Anasazi Great Drought of 1275 to 1300 is commonly cited as the last straw that broke the back of Anasazi farmers, leading to the abandonment of the Four Corners.

Extremist politics and religious zeal can be anything from external forces that invaded the Anasazi lands and took over like occupying Nazis, or internal strife over which priests to follow, erupting like a series of Mafia turf battles that became so intolerable everyone decides to escape.

The end of the Anasazi heyday was characterized by widespread violence, especially in the Chaco Canyon outliers, and social-control cannibalism, a subtle form of warfare and an outrageous form of political control, seemed to be a mechanism for the elites of Chaco Canyon to ensure the outlying farmers continued to supply them with food, even when times were tough.

But even this fails if the farmers can’t grow enough food to even sustain themselves.

Religious zeal, most interestingly, can also mean a high-powered belief system that sprang up somewhere else and attracted all the remaining Anasazi to a new holy land. The most likely candidate for this is the Kachina cult, which appeared around A.D. 1325, about a generation after the Anasazi disappeared from the Four Corners region.

But religion can also be highly political, and can be related to the religious-political power structure of an elite minority of governor-priests who hastened the Anasazi collapse with their policies and practices that failed to adapt to changing environmental and social conditions—such as the extreme building sprees that characterized Chaco Canyon in the generation or two preceding its collapse.

Most likely, it’s a complex combination of two or three (or more) of these simplistic causes. It’s easy to imagine an overbearing class of leaders who used cannibalism and violence to coerce the surrounding communities into providing food and laborers for their frenzied public works programs in Chaco Canyon, combined with climate change that reduced the surplus calories farmers could provide, creating a volatile cultural environment that would make a new and distant religion look very appealing as a way to salvation.

And finally, when a culture has more rich people to support than poor people to sustain them, then whole system collapses for everything. There is ample evidence of this as contributing to the Anasazi collapse.

The Anasazi culture is not the only one in human history to have collapsed, unfortunately, and the patterns are similar. Even today, we can see in our own American culture an upper class supported by increasingly extreme income inequality (the growing “surplus” productivity of average workers flows entirely to a tiny ultra-rich minority), a climate that is changing (exacerbated by our own actions), and a rise of religious fervor (marked by increasing rejection of science and rational thought).

This line of inquiry, research, and thinking led directly to my contemporary thriller, Price on Their Heads: A Novel of Income Inequality and Mayhem.

For now, let’s look at evidence for why the Anasazi collapsed. In subsequent Author Notes, we’ll examine how Anasazi wealth and productivity was distributed, and similarities of modern trends in income inequality with Anasazi inequality.

Drought, or climate change

The Anasazi were amazingly successful in a difficult environment for a very long time

Environmental problems, especially major droughts and episodes of streambed erosion, tend to recur at intervals much longer than a human lifetime or oral memory span. Given those severe difficulties, it’s impressive that Native Americans in the Southwest developed such complex farming societies as they did. Testimony to their success is that most of this area today supports a much sparser population growing their own food than it did in Anasazi times. —Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed, by Jared Diamond

The Anasazi flourished from A.D. 900 to 1300, which is nearly twice as long as the United States has been in existence. (And the Puebloans who descended from them, in much reduced numbers, have 700 years under their belt.)

So even though the Anasazi culture ultimately collapsed, it was extraordinarily successful for a very long time in a very difficult environment.

Will we last as long?

The U.S. Southwest is a marginal environment for agriculture at best

Favorite single-factor explanations [for the Anasazi collapse] invoke environmental damage, drought, or warfare and cannibalism. Actually, the field of U.S. southwestern prehistory is a graveyard for single-factor explanations. Multiple factors have operated, but they all go back to the fundamental problem that the U.S. Southwest is a fragile and marginal environment for agriculture. —Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed, by Jared Diamond

If farming were easy and productive in spite of drought, the Anasazi would likely not have collapsed, but would have remained in place in one political form or another until the arrival of the Spanish in Pueblo country in 1539.

Living and thriving in a precarious environment, especially in a complex culture, requires a system that can react efficiently to changing conditions. That means a hierarchical structure that is prescient, wise, and flexible, or a flat structure that rewards individual or small collectives of farmers for innovation and best practices.

The Anasazi had neither.

Chaco Canyon couldn’t grow enough food to support itself