Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 776

November 26, 2018

How to Manage Morale When a Well-Liked Employee Leaves

kumacore/Getty Images

kumacore/Getty ImagesIt’s a dreadful moment when a well-liked member of your team tenders their resignation. You experience a cocktail of emotions ranging from fear about how the rest of the team will react, to frustration at having to add recruiting to your already hectic calendar. The worst is the lingering feeling of being rejected. As with most difficult situations as a manager, how you handle the resignation will affect more than just you. How you respond will influence whether the person’s departure becomes a typical bump in the road or the inflection point to a downward trend for your team.

Before sharing the news with anyone, take some time to consider your response carefully. This allows you to grapple with your own reactions before you’re forced to manage those of your team members. If you move too quickly and try to communicate a positive message while harboring anxiety, frustration, or bitterness, those potent emotions will show through in your body language. When your words are positive but your body language telegraphs concern, your team will notice the incongruence and infer your intent from what you’re showing rather than what you’re saying.

Once you’ve reflected on your own reaction, you can work through a process that will minimize the damage of a well-liked team member resigning.

Start by helping everyone celebrate the person who is leaving. It’s understandable if you feel like downplaying the person’s departure, in hopes that no one will notice. It just isn’t likely to work. Losing a well-liked colleague will create concern and even grief for your team and invalidating that grief removes an important part of the process. Letting the person slip out the door unheralded will suggest that you don’t care. Don’t make the mistake of minimizing the moment.

You and Your Team Series

Retention

How to Lose Your Best Employees

Whitney Johnson

To Retain New Hires, Make Sure You Meet with Them in Their First Week

Dawn Klinghoffer et al.

Why Great Employees Leave “Great Cultures”

Melissa Daimler

Instead, be at the front of the “we’ll miss you” parade. Throw a party to wish the person well. Say a few words about some of the great things the person contributed to the team. Laugh about inside jokes and shared experiences because, as you do, you’ll not only make the person who’s leaving feel good about your team, you’ll strengthen the bond among the people who remain.

Recalling these stories will also put a smile on your face, which is much better than the look of terror that might be associated with your inner voice that’s saying, “What will we do without her?” or “What if others start to follow suit?” That face will only make your team more nervous when they’re looking to you for reassurance. Your words and body language should convey that it’s normal and natural for people to move on.

Once you’ve thrown the party the person deserves, ask them for a favor in return — their candor about what you need to learn from their departure. Even if your organization has a formal third-party exit interview process, conduct your own interview. Ask the person to be honest with you as part of the legacy they can leave in making you and the team better in the future. Prepare your questions carefully and get ready to take the lumps.

You’ll need to have good questions and follow-up prompts to get past the pat answers such as “I was offered higher compensation” and “It’s an opportunity I couldn’t refuse.” You need to identify what factors contributed to the person taking the call from the recruiter in the first place. You can make these questions less pointed by asking, “What advice would you give me to prevent another great person like you from taking a call from a recruiter?” “What do I need to know that people aren’t telling me?” “How could I improve the experience of working here?” By making the questions more generic and less personal, the departing employee might feel more inclined to share any uncomfortable truth.

You can also seek feedback about things beyond your control, such as, “What other messages does the company need to hear?” “What factors would contribute to a better experience here?” Throughout the discussion, your emphasis should be on asking great questions. Do as little talking as possible and instead, listen carefully and objectively.

After the exit interview, your head will be full of powerful, sometimes conflicting thoughts and feelings. Give yourself a night to sleep on it and then start the process of putting your insights into action. First, lean into the uncomfortable conversations. Whether one-on-one or in team meetings, dig into any themes that have merit. Share your hypotheses and ask people to clarify, refine, validate, or challenge how you’re thinking.

For example, you could say, “I’m coming to understand that the biggest problem is not the workload, but the lack of focus. What do you think? Is it true, false, or only half the picture?” This process of generating and testing hypotheses will not only help you make the most targeted changes, it will also help you strengthen the connection with your remaining team members.

As you listen to their responses, go beneath the facts and information they’re sharing with you and watch and listen for what they are feeling and what they value. Where does their language become stronger (e.g., “we always do this,” or “never do that”), suggesting that they are frustrated or angry. Where does it become weaker (e.g., “I guess we…, or “I think sometimes we might”), hinting that they might feel hesitant or powerless. What is their body language telling you? When you spot an emotional reaction, ask a few more questions to understand what’s beneath their feelings.

Through all of these conversations, try to discern whether one great person resigning was a single point or the start of a pattern. Be open about what you can do differently and advocate for the changes from other stakeholders that will make your team a better one to work on.

The insights you glean from conducting your own exit interview and testing your hypotheses will be valuable, but don’t lose sight of the most important ways that you contribute to the morale of your team — by positioning them to do meaningful work. Double down on the management essentials. Make sure everyone is clear on your expectations, especially on the highest (and lowest) priorities for the team. Have frank conversations to ensure people feel like they have the requisite skills and resources to do their jobs well. And pay more attention to the feedback, coaching, and celebrations that will motivate them and keep them engaged.

If there was a problem on your team you were unaware of (or trying to ignore) it might take losing a well-liked employee for you to recognize the severity of the issue. Work through your emotions and then start a virtuous cycle by celebrating the departing employee, seeking their candid feedback in an exit interview, forming and testing hypotheses about how to improve your workplace, and making meaningful changes that make your team feel heard and valued. Losing one team member might end up being a relatively low price to pay if it leads to better morale all around.

November 23, 2018

What Sales Teams Should Do to Prepare for the Next Recession

Photographer is my life./Getty Images

Photographer is my life./Getty ImagesThe current economic expansion is long by historical standards, and thus the risk of recession rises with each passing month. Recessions catch many companies by surprise, with predictable results. In the 2001 recession, total sales for the S&P 500 declined by 9% from its pre-recession peak to its trough 18 months later—almost a year after the recession officially ended. But these periods also present opportunities for well-prepared companies to take advantage of the turmoil and gain share.

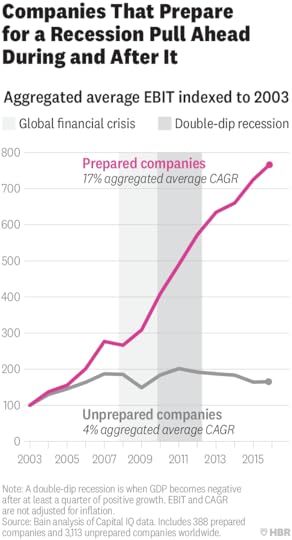

The best time to undertake major changes that will strengthen a company during recession is before it hits. Prior to the past recession, both eventual winners and eventual losers in a group of 3,500 companies worldwide experienced double-digit growth rates. Once the recession struck, however, performance began to diverge sharply – the winners continued to grow while losers stalled out. The performance gap widened during the recovery (see chart below). What did the winners do that losers didn’t? They pursued a variety of tactics before the recession that were designed to fortify the firm when the downturn hit – moves both within sales and beyond like adding a low-cost channel to serve small accounts or simplifying the product assortment.

We’ll focus here on what the sales organization should be doing now to prepare for the next recession, with an eye toward using new digital tools. The starting point, of course, must be to make sure you have the basics squared away: aligning sales capacity with the market opportunity (capacity tends to get rusted in place, leaving companies over- or under-resourced); sweating the details of daily execution (things like putting controls around discounting); and getting the back of the house in order (a nimble commercial operations groups is critical).

Digital tools and analytic techniques that have flourished in recent years can help make sure those basics are taken care of. Our recent benchmarking of nearly 900 B2B companies underscores the importance of these tools. On average, roughly four times as many winners – defined in this case as those companies that grew absolute revenue at a significant rate and gained market share within their industry over the previous two years – as losers have digital tools embedded into their core commercial capabilities. Digital tools can also open new go-to-market approaches.

Zero-base sales capacity. Too many sales teams use outdated practices in making account and territory assignments. They rely on backward-looking sales data and broad-brush reports to calculate overall market size and gauge how many reps they need and where to assign them. Digital tools can help make more accurate matches. Case in point: Vertiv, a provider of digital infrastructure to data center and communications networks companies, has built an opportunity calculator using a heuristic model powered by a few salient data points such as the number of server racks a facility can hold. The calculator quantifies the total spending for three main product lines within each of the top 100 accounts and estimates the market for smaller accounts in each territory. With this new process, Vertiv recalculated the potential market of its top five customers, discovering that the potential market was 50% bigger than it had previously estimated ($1.8 billion vs. $1.2 billion). Armed with the revised estimate, Vertiv revised their account coverage to capture the newly discovered opportunity.

Know when to walk away. Many sales teams lose track of which accounts consume most of their time and how they spend the time they do have with customers. Worse, most don’t have a quantified view of profitability by customer, product line and transaction.

To counter this problem, one cloud services provider went through a data-intensive effort to quantify transaction-level profitability and concluded that, no matter how it cut the data, deals under $2,000 were unprofitable. This analysis gave executives a rationale for prohibiting the smaller deals, and, with the sales team focused on closing larger deals, the company hit its sales plan one quarter later, after several quarters of misses.

Amplify low-cost sales channels. In other situations, rather than walking away from smaller revenue streams, some companies devise a channel that can close small deals profitably. It’s a myth that a field sales rep always needs to touch the customer in order to make a sale; in some cases an inside sales group is the cost-effective way to pursue a sale.

Consider the case of an online advertising and software company serving car dealers. After a series of acquisitions, the company’s sales force was underperforming. In particular, selling to and servicing smaller dealers became so costly that it led to low or negative margins for those customers, and consumed too much sales rep time. For smaller dealers, the company shifted to an inside sales center that not only reduced costs but also improved the dealer experience by increasing the attention paid to a typically underserved segment. Sales reps, meanwhile, were freed up to spend more time on larger project sales. As a result, the company increased its new customer acquisition threefold over the prior year and reduced its customer attrition by a healthy margin.

A shift to inside sales usually requires better digital marketing capabilities. New data sources and predictive analytics software can help inside sales organizations identify target accounts and allocate marketing and sales resources in real time. For example, an IT services company uses DiscoverOrg to mine organizational data that might indicate intent to purchase, such as job postings for a vice president of network. After deploying this and other digital tools, the company’s sales team doubled its rate of scheduling a first meeting with a prospective customer.

Detect and reinforce effective behaviors. To understand what separates top performing sales reps from the rest, companies have increasingly turned to analytics engines that mine online calendars and email traffic in order to help identify exactly which behaviors correlate with superior performance. Those behaviors can serve as the basis of training, reinforced daily by front-line managers.

A B2B technology supplier used Microsoft Workplace Analytics and other digital tools to track the behaviors of its sales reps. The data highlighted that top performers were three times as likely to interact with multiple groups inside the company, twice as likely to collaborate with peer reps, and 50% more likely to have weekly pipeline reviews with direct managers. Training on such behaviors, consistently reinforced by managers, can lift the productivity of lower performers.

Automate account management. Strong account managers keep an up-to-date view of the opportunity, share of wallet, decision makers and influencers, and actions needed in each account. Software applications such as Revegy and Altify automate this process and plug into a firm’s customer relationship management platform, turning a tactical opportunity-tracking tool into a powerful strategic planning tool.

Analytics can also support retention and cross-selling efforts. An industrial equipment distribution company uses artificial intelligence powered by Lattice Engines to identify the right products to cross-sell to customers. In their pilot, sales reps with the AI recommendations achieved 3% to 4% higher sales than those without. Since adoption, the distributor has seen revenue lift across all of its reps.

Streamline and digitize the back office. Commercial operations groups tend to be early targets for cuts in a recession. It pays to get ahead of cost pressures here by digitizing and automating large portions of the work, which reduces the need for employees to pull reports and manually reconcile numbers. The best commercial operations groups use their staff to execute analytics that produce valuable insights, such as mining the installed customer base for cross-selling opportunities.

Another digital opportunity involves the bid desk or “configure, price, quote” process. For instance, one telecom company uses an iPad application to support executives’ review of deals. The app pulls in the level of risk, commercial viability, and strategic opportunity for deals of similar size, plus margin and expected win rate, making it easy to access the information in one place.

Raise the game in pricing. Almost all B2B companies could do better on pricing. Bain’s recent survey of sales and marketing leaders at more than 1,700 companies found that 85% of companies believe that their pricing decisions could be improved, yet only 15% believe they have the right tools and dashboards to do this. Even high performers on pricing see opportunities to unlock additional value through digital approaches including:

Dynamic deal scoring. By mining past transactions, current customer segmentation and preference data, win rates, and competitive pricing data, new software tools can create statistically derived pricing guidance tailored to each deal.

Algorithmic pricing. With external market, customer, and macro data on current supply and demand, competitor pricing or weather, analytic tools can determine the optimal price for a moment in time.

Iterative machine learning. AI-supported A/B testing in fast cycles can determine best price points at a SKU level to achieve margin and volume goals.

Start small, fail fast

The vast number of digital sales tools can be overwhelming. Where should sales executives start?

We have seen commercial organizations successfully work through these questions with small teams that test and learn as they go. Many use Agile principles, setting up sprints to produce real business results, not just an improved process. Their sole measures of success are incremental sales and profit margin. Starting small allows the team to quickly work out kinks in the process and try things that might not work, because the consequence of failure is also small. And successes can be scaled up quickly.

There’s little point trying to predict a recession with any precision, because most often you’ll be wrong. But winning companies focus on controlling what they can control well before and during the recession, including their sales organization and go-to-market tactics. And becoming more proficient at digital sales technologies gives companies an upper hand over competitors that lag in digital adoption. Armed with the right digital tools, sales teams might almost look forward to the coming recession rather than fearing it.

The Subtle Stressors Making Women Want to Leave Engineering

Luis Alvarez/Getty Images

Luis Alvarez/Getty ImagesFemale retention in engineering remains a persistent problem. Even after overcoming hurdles to enter the profession, women leave at much higher rates than men, often because of the stress that comes with being female in a male-dominated field. This stress can be quite overt, like when women face instances of gender discrimination or harassment; but our research shows that it can also be subtle, like when women feel that their contributions are less valued than their male peers’ because tasks and roles have been gendered. When experienced daily, this kind of subtle stress can become depleting.

To build a deeper understanding of these experiences and how women deal with them, we interviewed and surveyed more than 330 engineers in the U.S. (43% female, 57% male) from 2013-2017, and spoke with more than 20 female engineers at professional conferences in the U.S. and Canada. These engineers varied in age from 22 to 50 and came from multiple engineering subfields.

Our data provides insight into engineers’ professional identity and experiences of work – their approaches to work, career path decisions, work stressors, and intentions to leave the field. Our findings, combined with our other research on identity and resilience, suggest that female engineers experience stress from subtle and not so subtle cues that their skills and their work are not valued within the profession. This stress increases feelings of not fitting in and made women more likely to think about leaving. But we also identified important resilience strategies women can use to overcome it.

Stress from Gendered Tasks and Career Paths

Early in their training, engineers learn that there are two sets of skills required in engineering: “hard” engineering skills (such as technical ability and problem solving) and softer “professional” skills (such as communication, relationship building, and teamwork). They also learn that these skills are gendered, with the former viewed as more masculine, more revered and higher status; and the latter viewed as more feminine and lower status.

Our research shows that many female engineers felt drawn to tasks that were not purely technical. Indeed, many of the engineers we talked to described enjoying and excelling at tasks involving people, communication, and organization skills, in addition to technical skills. As one female engineer noted:

I knew I didn’t want to sit in front of a computer and run model and do calculations all day. That’s just not my personality, even though I have that engineering background. Also, I’m a good people person, and that has often drawn me to working with other people, instead of being an individual contributor and just outputting work, submitting it to someone, and sitting on my own all day every day.

While some women gravitated toward these tasks based on their interests, mentors also encouraged women to take on tasks and roles that are consistent with the “professional” side of engineering. One male engineer described how he witnessed this happening to a female colleague:

They had her assigned to non-technical things, arranging things, putting things together, and representing the team in team meetings. She did very well at that, and I’d have to say being there, she brings strong communication skills to the table. And as a result, they kind of want to put her in a position full time because she’s done so well.

However, as one woman noted, others tended to view these skill sets as less aligned with what it means to be a “real engineer.” Because there is a tendency to define “real” engineers in terms of technical skills and values tied to being a technical specialist, many women felt that their unique skills were not always valued or recognized. For example, one told us:

It seems like these things, these skills, these traits that I’ve honed for a very long time…one might label as soft skills maybe…are not really the kinds of things that get rewarded as much on day to day. Or are being recognized.

Our interviews with male engineers confirm these beliefs. Men said that their female co-workers are often drawn to the “less valuable” tasks at work. Specifically, they pointed out that their female coworkers’ tended to excel at the social aspects of the job (like relationship management and multitasking), but that these aspects were merely “peripheral” to the real, technical work.

Research also shows that women are disproportionately likely to move away from the most technical career paths and toward roles that involve technical supervision or management as their careers progress. We found that while some women pursued these technical supervisor or management roles based on their preferences, some were also mentored into these roles. Other evidence shows that this can happen as a result of diversity initiatives and stereotypes about women being more skilled at communication and coordination than men.

One female engineer told us she was encouraged by her boss to take on a managerial role because she was perceived “to be extroverted” and “to have good people skills.” A male engineer we interviewed echoed the idea that women are particularly suited for managerial roles:

Women do better at managerial roles…a lot of them display the traits to be a good manager, they care about their people, they care about how they communicate, how they develop products…If you have 10 engineers in a room, from our company, they’re all going to be smart, but it’s the one who can communicate well, the one that can get people behind them…they’re stereotypically female.

The problem is that managerial roles are less valued in engineering. Engineering firms often have a prestige hierarchy, where the most technical career paths are perceived as the highest status and most valuable, and the less technical career paths, including project or product management, are seen as less critical and even less desirable. In fact, many of our interviewees – especially men – described managerial roles as undesirable, saying: “I don’t like to be a called a manager” or “Maybe they get rewards out of it, but I don’t see how I could do that.”

When women disproportionately occupy roles that are less valued or unwanted, it can reinforce stereotypes about female engineers being less technically skilled, make them feel less respected, and create the illusion that they are not a “real engineer.” Decades of social psychological research shows that feeling like you and your work aren’t valued by others in your organization creates chronic and persistent psychological stress. This stress may challenge female engineers’ ability to cope with other stressors, such as high work demands and persistent bias in the workplace, leading them to burn out and consider exit.

However, though some of the engineers we sampled reported intending to leave the profession, many persevered in the face of these obstacles and lead fulfilling careers. We gained some insight into how these women effectively deal with this stress. They did “professional identity work” to minimize the rift between their gender and professional identities; and their experiences may help other women in engineering become more resilient and lead fulfilling and authentic careers.

Building Resilience Through Professional Identity Work

Ask yourself what you want. Given the bias in engineering to prize technical skills and specialization above all else, it is easy to feel pressured to privilege external expectations over your own voice and values, creating a sense of being inauthentic. Many women we spoke with described feeling “different from other engineers” or like they need to be “a different person at work.” Try privileging your own dissenting inner voice, rather than fighting to re-program your own motivations to become aligned with the majority perspective.

One way to feel more authentic is to reflect on your personal and professional values. Engineers should ask themselves: What is important to me, and what is not? What experiences are most appealing and how can I get them? What support do I need and from whom? What are my strengths and weaknesses and what do I want to change?

Being introspective about your aspirations, proficiencies, and sources of energy helps silence the external noise that undermines the sense that your work is devalued, and creates a sense of being true to oneself. This in turn, helps build confidence in your career choices, and reduces stress from deviating from the norm. It can also help you to recognize when you have been silently led astray – pursuing tasks and roles that you have been tracked into rather than the ones you enjoy – and help you get back to what is most important to you.

Female engineers also need to be conscious about decisions to take on certain tasks, roles and career paths. When presented with a career or task “opportunity,” it is critical for women to develop a habit of asking themselves: “Am I taking on this role because I like it and it fits with my career goals?” or “Am I taking on a task because someone else thinks it fits my skill set?” One engineer who had been encouraged by her superior to pursue a managerial path told us:

I recently had a one-year stint in the managerial path. It was something my management and our portfolio managers really pushed for because they felt I had skills – I am articulate, good with people, have excellent presentation skills – that would really allow me to succeed. I hated it, switched back to a technical path, and disappointed most of my champions. Now I’m thankful that I know myself better not to do it again.

This doesn’t mean you should turn down roles without exploring them; rather you want to tune into yourself for feedback on what tasks and roles suit you. Another engineer we talked to found her niche in engineering through a process of reflecting on her managerial interests. She said:

I think it’s a matter of finding out what you are cut out for…Now I’m feeling like ‘Yeah, turns out I do know what I’m doing, and I’m pretty damn good at it’…Go find what you are cut out for, what are you passionate about.

Embrace your complexity. Female engineers also need to learn to embrace their identity complexity — the fact that they may hold both feminine and scientific values — rather than trying to force themselves into socially constructed gender or engineering boxes. This complexity will allow you to embrace the uniqueness you bring to the profession, thus reducing feelings of dissonance and tension.

Focus on the synergies between your identities (gender, profession, role), rather than the conflict. What are the benefits of being a woman in engineering or a female engineering manager? What are the benefits to the company of someone who has technical, organizational, and communication proficiencies? How can you articulate these benefits? Indeed, the qualities that women bring to engineering, such as effective communication and management skills, and the ability organize the work of teams, are suggested to be critical to the future of engineering.

Embracing and helping others to understand the advantages of your complexity can help you express your unique and important “brand” in the engineering workforce, as someone who possesses a broad set of skills, interests, and aptitudes. When you’re in a role that embraces your unique combination of skills and abilities, it can increase satisfaction and lower stress. As one woman explained:

If you get that my interests are not traditional and they’re not textbook thermodynamics, there’s no way I could not do a role like that. [The role I have chosen] is more of an untraditional engineering career path and its fun. And it’s very technical [but]…it’s outside the box. It’s creative. It’s kind of a combination…The balance between having the technical expertise and the business understanding puts me in unique place in engineering and the technical community…I’m a happy woman.

Our research shows that women engineers experience hidden stress stemming from the gendering of tasks and roles in engineering, and subsequently the ways in which female engineers perceive that their work and roles are devalued within the profession. By reflecting more on what they want out of work and embracing their complex identities, women in engineering may become more resilient in the face of stress to create long, meaningful careers.

November 22, 2018

Green Bonds Benefit Companies, Investors, and the Planet

Monalyn Gracia/Corbis/VCG/Getty Images

Monalyn Gracia/Corbis/VCG/Getty ImagesThe past five years have seen explosive growth in “corporate green bonds” issued to finance climate-friendly projects. While investors bought just $3 billion of these bonds in 2013, they scooped up $49 billion worth in 2017, bringing the total sold since 2013 to $113 billion at an average of $308 million per offering. A wide range of companies including Apple, Unilever, and Bank of America have issued green bonds in recent years, and the trend is likely to continue. Despite this boom, little is known about the impact of these bonds. Have they delivered positive environmental results? Do they contribute to the issuing companies’ financial performance? The answer to both questions is a resounding yes.

In a recent analysis of the 217 corporate green bonds issued by public companies globally from January 1, 2013 to December 31, 2017, I show that they yield a positive stock market reaction, improvements in financial and environmental performance, an increase in green innovations, and an increase in stock ownership by long-term and green investors.

How the stock market responds

The issuers’ stock price increases around the announcement of green bond offering, indicating that investors expect the bonds to contribute to shareholder value. (New information is provided to the market on the announcement date, as opposed to the issue date. Further, the analysis includes the announcement date and the previous trading day to account for the possibility that some information may have been known to the public prior to the announcement). In this two-day event window the average cumulative abnormal return (CAR)—that is, the stock return in excess of the “normal” market return was 0.67%. So, if the stock market (say, the S&P500 index) goes up by 1% over these two days, the stock of the green bond issuer increases, on average, by about 1.67%. All other periods before and after the two-day event window yield insignificant CARs, which confirms that the results are not driven by unrelated trends around the time of the announcement.

These results hold virtually steady even when adjusted for industry-specific performance and potentially confounding events like the announcement of equity issues, regular bond issues, or quarterly earnings. Results do differ, however, depending on several variables.

First, the stock price increase around the announcement of the bond issue is about twice as large for green bonds that have been certified by independent third parties such as Sustainalytics, Vigeo Eiris, Ernst & Young, and CICERO. Some 69% of corporate green bonds were certified by independent third-parties to establish that the proceeds are funding projects that generate environmental benefits. Certification is rigorous and costly, so certified green bonds likely represent a more credible commitment toward the environment, which could explain the stronger stock market response.

Second, the stock price increase is larger for companies operating in industries where the natural environment is financially material to the firms’ operations. For those companies, green projects contribute more substantially to financial performance.

Third, the announcement returns are larger for first-time issuers, compared to seasoned issuers. Arguably, first-time green bond issues, compared to seasoned issues, are more likely to provide new information to the investor community about the firm’s environmental commitment going forward. The second and third time around investors are already aware of the firm’s commitment to sustainability, which is reflected in a weaker stock market reaction.

Improvements in financial performance

Green bond offerings are also associated with a 2.4% increase in long-term value, measured by the ratio of the firm’s market value to the book value of its assets. (All results are averages across all green bond issues.) Moreover, issuers of green bonds, compared to a control group of companies that issue bonds but not green bonds, saw an improvement in operating performance as measured by the return on assets (ROA). In the long run (two years after the green bond issue), ROA increases by 0.6 percentage points. Because investments in green projects take time to pay off, higher operating profits only appear after two years, while no effect is found in the short run.

Better environmental performance and more green innovations

Several measures suggest that after issuing green bonds companies improve their environmental performance. Their environmental score rose 6.1 percentage points on the Thomson Reuters’ ASSET4 scale, which is based on more than 250 key performance indicators such as CO2 emissions, hazardous waste, recycling, and so on. They reduced their emissions by 17 tons of CO2 per $1 million of assets. Moreover, they increased their green innovations―measured by the ratio of the number of “green” patents filed to the total number of patents they filed in a given year― by 2.1 percentage points.

Increase in ownership by long-term and green investors

Companies that issue green bonds also appear to adopt longer time horizons—which is particularly important given rising concerns about corporate short-termism. The long-term index (a measure of long-term orientation based on a textual analysis of the firms’ annual reports) of green bond issuers increases by 3.9 percentage points. Corporate green bonds also help attract investors who care about the long term and the environment. The share of long-term investors increases from 7.1% to 8.6% (a 21% increase), and the share of green investors from 3% to 7% (a 75% increase).

Taken together, the findings that green bonds trigger a positive market response, improve financial and environmental performance, and attract long-term and green investors, suggest that this relatively recent innovation in impact investing holds significant promise for fighting climate change globally—whether governments act or not.

Making Kindness a Core Tenet of Your Company

Hiroshi Watanabe/Getty Images

Hiroshi Watanabe/Getty ImagesScan the newspaper headlines, or switch on cable news for a few minutes, and it’s easy to conclude that we are living through harsh, mean, divisive times. But a recent column in the Washington Post reminded me of a truth that is even easier to overlook: Just as bad behavior tends to spread, so too does good behavior. Kindness, it turns out, is contagious. The column highlighted the work of Stanford psychologist Jamil Zaki, who documents what he calls “positive conformity.” In his research, “participants who believed others were more generous became more generous themselves.” This suggests that “kindness is contagious, and that it can cascade across people, taking on new forms along the way.”

Zaki’s insight is vital for improving society, but it applies to companies too. Almost every leader I know wants his or her colleagues to go above and beyond normal standards of service, to impress customers with their kindness. Many of these leaders also believe that achieving this goal is largely a matter of policies and procedures — kindness as a directive. Actually, the way to unleash kindness in your organization is to treat it like a contagion, and to create the conditions under which everybody catches it.

Consider one instructive case study. I recently immersed myself in the customer-service transformation of Mercedes-Benz USA, the sales-and-service arm of the German automaker. When Stephen Cannon became president and CEO of Mercedes-Benz USA, he recognized that success was about more than just his vehicles. It was about how much the people who sold and serviced the cars cared and how generously they behaved. “Every encounter with the brand,” he declared, “must be as extraordinary as the machine itself.” And almost every encounter with the brand, he understood, came down to a personal encounter with a human being in a dealership who could either act in ways that were memorable, or could act the rote way most people in most dealerships act.

Cannon also understood that if he wanted to influence the behavior of more than 23,000 employees at Mercedes dealerships, there was no rule book he could write to engineer a culture of connection and compassion. Instead, he had to convince dealers and their staffers to join a grassroots “movement” that treated kindness like a contagion.

“There is no scientific process, no algorithm, to inspire a salesperson or a service person to do something extraordinary,” Cannon told me. “The only way you get there is to educate people, excite them, incite them. Give them permission to rise to the occasion when the occasion to do something arises. This is not about following instructions. It’s about taking a leap of faith.”

Over the last few years, this leap of faith unleashed all sorts of everyday acts of kindness. There was one dealer who’d closed a sale and noticed from the documents that it was the customer’s birthday. So he ordered a cake, and when the customer came in to pick up the car, had a celebration. Then there was the customer who got a flat tire on the way to her son’s graduation. She pulled into a Mercedes dealership in a panic and explained the problem. Unfortunately, there were no replacement tires in stock for her model. The service manager ran to the showroom, jacked up a new car, removed one of its tires, and sent the mother on her way. “We have so many stories like this,” Cannon says. “They’re about people going out of their way because they care enough to do something special.”

There was another ingredient to the Mercedes-Benz contagion. It’s more natural for front-line employees to show kindness towards customers, it turns out, if they are motivated by genuine pride in what they do. Harry Hynekamp, a 15-year veteran of Mercedes-Benz USA, became the first-ever general manager for customer experience. As Hynekamp and his team traveled across the country, they discovered that “pride in the brand was not quite as strong as we thought, the level of engagement with the work not as deep as we thought.” What really shocked them is that nearly 70 percent of front-line employees had never driven one of the cars outside the dealership lot. They’d repaired them, ordered parts for them, but they’d never been behind the wheel on the open road.

How could people take genuine pride in the brand, Hynekamp wondered, if they’d never themselves experienced the thrill of driving a Mercedes-Benz vehicle? So he created a program through which all 23,000 dealership employees got to drive a new Mercedes-Benz for 48 hours. The company put close to 800 cars in the field, at a cost of millions of dollars. Employees often timed their turns behind the wheel to correspond with important events — picking up grandma on her 90th birthday, driving a daughter and her friends to a Sweet 16, bringing a newborn baby home from the hospital. The participants took photos, made videos, and in one case, even wrote a rap song, to chronicle their 48 hours.

“The reactions were out of this world,” Hynekamp told me. He created an internal website to collect and share the stories. “Sure, people got to know the cars very well. But the biggest piece was the pride piece.”

This bottom-up, peer-to-peer commitment to customers at Mercedes-Benz USA is a powerful case study in service transformation. It’s also a reminder for leaders in all sorts of field: You can’t order people to be kind, but you can spark a kindness contagion.

November 21, 2018

Will Wall Street Be Able to Earn the Trust of Younger Investors?

Image Source/Getty Images

Image Source/Getty ImagesUber and Netflix have fundamentally shifted consumer behavior and disrupted incumbent firms. In our research, we’re beginning to see signs that Wall Street is being threatened by similar forces.

Uber and Netflix’s success were generated through two critical strategies. First, they created a combination of breakthrough product innovation and breakthrough business model innovation—the definition of category creation. Second, Uber and Netflix appealed to a younger superconsumer before they entered the category, which caught the market leaders flat-footed.

In financial services, there are signs that traditional products like mutual funds are beginning to wane. Higher-fee, actively managed funds lost $500 billion in assets since 2015, with much of it flowing to much lower cost passive funds (e.g. index funds). But total net inflows of money into all mutual funds and exchange traded funds is at its lowest levels since 2014.

Meanwhile, new investment exchanges and IRA accounts are emerging that provide alternative investments versus traditional stocks, bonds and mutual funds, that have similar liquidity but greater transparency, and were previously only available to the ultra-wealthy.

One next-generation example already available today is YieldStreet, which offers a wide variety of debt investments—including real estate, marine finance, and litigation finance–that have generated an internal rate of return in excess of 12.5% on half a billion dollars invested on the platform to date. Similarly, access to the world of startup investing was limited to “exclusive clubs” like venture capital funds and high net worth angel networks. Now, platforms like AngelList, WeFunder, and Republic enable ordinary retail investors to participate in this stage of a company’s growth. According to a survey we conducted with Research Now/SSI on investing and retirement of 2,000 nationally representative households, 15% of total households are extremely interested in this. Through these platforms, Main Street investors can screen startups by industry, review business plans, and ask questions of founders directly.

Perhaps the biggest sign of future disruption to traditional Wall Street incumbents is how young these alternative investment superconsumers are. Our data shows that the consumer that is ‘extremely interested’ in alternative investments is very young and high income, with an average age of 35 and average annual income over $130,000. In contrast, the consumers least interested in alternative investments is in the mid-fifties with average income. It’s clear more money could go to investments: according to a survey of 3,000 Americans aged 18-44, one in three spent more money on coffee than they invested in a year. This is not surprising, since 67% find investing scary and confusing and 52% believe the ‘investment market is rigged against people like me.’

Remember that many younger investors grew up in the 2008 recession and perhaps never trusted the stock market. Growing more investors (especially younger ones) by getting more of them off the sidelines is key; the question is how to do so?

Disruptors show the way by bringing investments that are easier to understand and more purpose- and passion-driven, both of which are highly appealing to millennial investors. You can now invest in ‘fix and flip’ real estate investments via companies like Groundfloor, Lending Home, and PeerStreet. They allow investors to lend money to ‘fix and flippers’ who buy a home, renovate it and sell it at a higher price. WeFunder, a startup exchange, focuses on finding high-purpose-driven and high-passion investments, has found that many of its investors are themselves superconsumers of the companies they were investing in. They found their superconsumers were excited to invest, as they clearly had a stake in ensuring the company’s long-term viability, much like Kickstarter does with product innovation but with the added benefit of investment growth potential.

How much disruption could Wall Street be facing? It depends on how prepared and proactive they are. The alternative investment superconsumer represents about 20 to 25 million households who have approximately $25 trillion dollars in investable assets and nearly $8 trillion in retirement assets. These consumers are willing to shift 20 to 25% of their retirement assets—nearly $2 trillion dollars—into an IRA that specializes in investing into alternative assets. Eric Satz, CEO of AltoIRA says, “Retirement dollars are the jet fuel for democratizing alternative investments.”

The youth of these superconsumers is perhaps the most critical insight. Incumbent Wall Street firms never had a relationship with these younger superconsumers, so it was much harder for them to anticipate the disruption.

Consumers who don’t enter the category at the normal point are particularly scary for traditional firms. By not entering at the expected age, they may never enter the category and show subsequent generations a different way.

ESPN was conducting business as usual until it peaked at 100 million subscribers in 2011; it’s declined to 87 million subscribers today, largely due to cord cutters who never had cable. New York City taxi struggles have been even more dramatic – taxi cab medallions there trade today at approximately $200,000 per medallion, down from as much as $1.3 million just five years ago, because young people adopted Uber instead of taxis, hurting taxi revenues.

The average age of a traditional wealth management firm’s customer is in the mid 50’s. Much like the threat that millennial cord cutters pose to cable TV companies, traditional financial institutions are not likely to see this coming and will face similar disruption challenges unless they take action now.

Building More Trust Between Doctors and Patients

pchyburrs/Getty Images

pchyburrs/Getty ImagesHealth care practitioners have traditionally relied on clinical heuristics to select, encode and process information from the patient. When a patient is presenting with multiple and complex issues, these heuristics reduce the patient’s difficult question of “what’s wrong with me” to easier ones, such as “is this person presenting with depression”? The use of heuristics is then reinforced by operationalizing evidenced-based care into protocols, procedures and checklists designed to increase efficiency and reduce variation in process.

The trouble with this approach is that medical professionals are so busy looking for what they’re trained to find that they can often completely ignore information staring them in the face. When Harvard Medical School famously conducted research in this area, 83% of radiologists studied did not see a gorilla superimposed on an X-ray, even when it was 48 times the size of the nodule they were looking for. Optical tracking devices showed the radiologists had all looked directly at the gorilla.

Insight Center

The Future of Health Care

Sponsored by Medtronic

Creating better outcomes at reduced cost.

While the heuristics-based approach is logical at one level – given the operational and cost pressures faced by health services – the impact on patients is that too many receive multiple diagnoses and treatments, without recovering. When Monash Health (an integrated health care provider based in Melbourne, Australia) gathered data, both quantitative and qualitative, in the form of patient journey maps and admissions and diagnostic information, we found that re-presentation among mental health patients was rising, even though the percentage of new patients presenting had fallen over the previous 10 years.

What’s more, over 50% of the most frequent presenters have had over four different psychiatric diagnoses and have received the recommended treatment for the conditions concerned. Further analysis revealed that the reason for this failure was the fact that underlying trauma issues in the patients concerned had not been treated. Because we had not been primed to attend to the significance of trauma in our patient’s lives, it was hiding in plain sight from us, like Harvard’s gorilla.

How could we avoid missing the gorilla in future?

Learning to see what lies beneath

The answer, our research told us, was to build strong trust-based patient relationships with our patients, in which clinicians could work more responsively with patients to uncover and eventually treat their traumas. This would require building a feedback loop in the treatment process to ensure the system could adapt and change.

To pilot this new approach, Monash Health established the new Agile Psychological Medicine Clinics (aPM Clinics). At each interaction, the clinician requests feedback from patients on treatment outcomes and their experiences of interaction with Monash professionals. This builds in an opportunity for patients to air their concerns and provide data in their own way, which takes clinicians out of their heuristic box. And although the process creates extra work on the spot, it also enables the therapist to respond and adapt promptly to what the patient is telling them and ensures that a patient is treated in the context of their culture and preferences.

The results from the experiment are encouraging. Patients visiting the clinics have on average reported high overall satisfaction levels (96%) with their work, dialogue, and relationship with their therapist. The patients receiving trauma treatment have experienced a 52% improvement in their trauma symptoms and a 39% improvement in depressive symptoms (from severe to mild). And, significantly, the proportion of patients in the group re-presenting themselves during treatment has decreased by 30%. All are clinically significant results.

Let’s turn to look at an example of what the new process is delivering

A Case in Point

In January 2016, Ash (not her real name) turned up in Emergency for pain and severe difficulty walking. She was admitted into the neurological ward for assessment; but no biological origin was identified. This was not her first visit to Emergency. Over a period of eight years, Ash had already received several psychiatric diagnoses from different specialists – PTSD, depression, and other disorders – and had remained on anti-psychotics all that time.

After the neurological admission in 2016, Ash was referred to the Agile Psychological Medicine Clinic. The clinic established that Ash’s first diagnosis for schizophrenia, which was treated with anti-psychotics, had been given after the traumatic birth of a son who turned out to have severe developmental issues. Through the years following she was not only her son’s primary caregiver, she was also in an abusive relationship.

Although Ash had been asking for treatment for her trauma since that traumatic birth and had repeatedly complained that the medication turned her from a smart woman to someone who could not make a sandwich without following written instructions, she had been caught up in a pattern of clinical activity that largely ignored the information she volunteered, and the question of her trauma was almost completely ignored

After just 14 sessions of treatment at the Clinic targeted on the trauma of her son’s birth, Ash no longer met the criteria for schizophrenia, PTSD, depression, or any of the other diagnoses she had received. She is off all antipsychotic medication, feels she has her life back and has been studying at university for the last two years.

Building empathetic, patient relationships is not only proving effective in treating seemingly intractable mental health sufferers such as Ash. We are finding that many chronic patients presenting with physical symptoms also benefit from the approach.

Keeping an Eye on Our Most Vulnerable Patients at Home

This is the motto of Monash Watch, a service that focuses on the small number of people who are identified as being at high risk of three or more admissions in the subsequent 12 months using an algorithm based on administrative and routinely collected clinical coding data. Since these “top 2%” of acute hospital presenters in any year are responsible for 25% of direct health care costs, the program aimed to reduce patients’ reliance on acute hospital services by helping them improve wellness.

Based on the Patient Journey Record System (PaJR), an analytics software developed by Carmel Martin, an expert in chronic illness and patient-centered care and an adjunct professor at Monash Health, the service offers patients lay telecare guides, who call participants one or more times per week. The same guide calls the same person each time, the goal being to build a relationship of trust with the patient.

After running through a simple script of health questions the guides discuss the patient’s responses with them and engage them generally in a relatively unstructured dialogue that is driven by the patient and which is recorded and analysed by PaJR. The software generates alerts if responses suggest health decline, and if a change in condition is confirmed, the patient is handed off to a clinician for follow-up.

The telecare guides can also detect changes in health status by listening carefully to the words in the responses, the change in intonation, and pauses, because they have come to know their patients as people, not just as anonymous check-a-box responses to questions. As they have grown into their jobs, they have become skilled at observing and communicating the signals and messages that patients give them. We call our tele-care guides “professional good neighbours” and that is exactly what they have turned out to be.

Over time Monash guides and coaches have observed a number of common features among their patients: many had lost a sense of purpose, had become depressed and/or anxious, and were experiencing pain. Some had resorted to self-medication with pills, opioids, and alcohol. By delving more deeply into the stories trusting patients told their tele-care guides, the Monash Watch team found that once again a history of prior trauma often lay at the roots of the conditions presented.

Most Monash Watch patients recognize that treatment – even for trauma – will be unable to significantly undo the physical impact of their past on their health but they also report that having someone lay who is in regular contact and is willing to listen to anything on their mind reduces anxiety and restores hope – and that itself has a positive impact over time, and helps reduce the frequency of unsettling visits to Emergency.

The general lesson that we have learned from these experiences is that building an empathetic, trust-based relationship with patients is not a nice-to-have but a must-have. It creates the possibility of identifying underlying hidden conditions whose treatment prevents the occurrence of overt symptomatic conditions that cause distress to patients and place huge strains on the capacity of healthcare services. Empathy saves not only lives but also money and time. It’s time to build a place for it in the clinical process.

Don’t Let Lazy Managers Drive Away Your Top Performers

Ricardo Lima/Getty Images

Ricardo Lima/Getty ImagesMany people believe that being a good manager only requires common sense, and that it is therefore easy to be one. If this were true, good managers would be commonplace at all levels of more organizations, and as a result, employee engagement and retention would be high. However, only 13% of workers worldwide are engaged at work, and employee turnover rates in the United States are at a 17-year high. As these statistics suggest, either most managers lack common sense, or good management is, in fact, quite challenging in practice.

As social scientists who study organizational behavior, we know that even in theory, being a good manager and retaining employees is difficult. Indeed, researchers have sought to understand how to cultivate a happy and productive workforce for more than 100 years. When we consider this body of work, it is evident that there are a multitude of factors that influence employee retention. In both theory and in practice, engaging and retaining employees is a complex endeavor, and it takes hard work to do it well.

When managers subscribe to the “common sense” view of management, they see little value in exerting effort when it comes to leading their teams. In turn, they become lazy managers. As explained below, we have observed at least two symptoms associated with lazy management: 1) a tendency for managers to blame low performance and turnover on employees, rather than on oneself or on the organization, and 2) a tendency for managers to look for quick fixes to complex retention problems.

You and Your Team Series

Retention

How to Lose Your Best Employees

Whitney Johnson

To Retain New Hires, Make Sure You Meet with Them in Their First Week

Dawn Klinghoffer et al.

Why Great Employees Leave “Great Cultures”

Melissa Daimler

Psychologists have long recognized that people often overestimate the role of personality and underestimate the power of the situation in shaping human behavior. When managers become lazy, they tend to make this fundamental attribution error more frequently and on a larger scale, believing that employees act the way they do because of who they are. By blaming employees for performance problems or retention issues, lazy managers free themselves from doing the hard work of considering how their own management style affects employee satisfaction, performance, and turnover.

Also, because lazy managers believe that good management is simple, when things go wrong, they are drawn to simple solutions that are easy to find. For example, when employee retention becomes a problem, lazy managers may be quick to suggest pay raises or bonuses as the antidote — a costly solution that may fail to address the underlying issue(s). The latest management fads may also be more appealing to lazy managers. Indeed, the sheer volume and availability of solutions to employee engagement and retention problems through blogs, books, podcasts, and other sources is greater than ever, and the reality is that much of it targets lazy managers seeking quick fixes.

Even though most managers realize that their employees want to be treated fairly, have meaningful work, feel a sense of accomplishment, and so forth, the extent to which employees feel these needs are being satisfied can vary on a daily basis. Thus, effortful management requires that leaders be more thoughtful and persistent in trying to understand why their employees may be thinking of leaving and what time, energy, and other resources are needed to increase their engagement. Given that even good managers can sometimes fall into this trap, what can you do if you and your management team are showing signs of lazy management?

First, when employees are disengaged, rather than asking what is wrong with them, managers should instead start by considering the possibility that management is doing something wrong. After opening their minds to this possibility, managers can determine whether this is the case by collecting data. For instance, quick, frequent “pulse surveys” may be useful for keeping tabs on how employees feel about their own jobs and the job that management is doing; likewise, self-development tools, such as the Reflected Best Self exercise, a tool that helps people understand and leverage their individual talents, may provide leaders with feedback that can help them use their strengths more effectively. In short, managers need to take the uncomfortable and intentional step of gathering evidence from others to inform what they can be doing to re-engage their employees. The good news is that by simply signaling to employees that a manager is willing to work hard and make meaningful changes, some employees will feel more supported and inclined to stay.

Second, managers who are willing to make the effort will find that there are ongoing advances in the practice and study of management which offer an ever-expanding set of tools for diagnosing and addressing employee retention challenges. Not every tool fit a given manager’s style and the organization’s circumstances. Therefore, good managers must not only continually learn, but also must have the discipline to verify whether the advice they do receive, even when based on strong evidence and best practices, will apply to their team. It can be useful, then, for managers to see themselves as behavioral scientists, and become comfortable pilot testing retention-targeted changes before fully implementing them. For example, before providing employees with customer feedback in order to stoke their prosocial motivation — that is, their interest in helping customers for altruistic, unselfish reasons — a trial run with a subset of employees can provide evidence regarding whether it will improve employee attitudes and performance, and if so, by how much. Fortunately, there are resources available to managers who want to learn more about “people analytics” and how to use it to improve their organizations.

Finally, when retention issues crop up, organizational leaders should consider whether lazy management is contributing to the problem. If managers are just going through the motions when it comes to employee engagement and retention, it could indicate that they lack the necessary time, resources, and motivation to do more. Since effortful management requires energy in the short-term, but does not pay off until down the road, some managers forgo their responsibilities to their people because they are too focused on meeting short-term objectives. To discourage lazy management, then, managers must be given the support, incentives, and direction needed to motivate them to dedicate time and energy toward more actively managing their teams. In addition, rather than blaming lazy managers for retention issues, leaders should take a critical look at their selection and promotion processes to determine why these individuals were placed into managerial positions in the first place. If they were promoted to manager because they have excellent technical skills, they may have turned into a lazy manager because they were taken away from what they do best. If managerial promotion processes do not focus on identifying those who are most likely to embrace the challenge of managing well, lazy management may spread throughout the organization.

Management is not easy, and it takes a lot more than common sense to develop and retain a highly motivated workforce these days. By abandoning the “just common sense” mentality associated with lazy management, managers can learn how their actions influence employees, stop looking for easy fixes, and exert the thought and effort that is uncommon in too many workplaces.

November 20, 2018

How to Set Up an AI R&D Lab

Paper Boat Creative/Getty Images

Paper Boat Creative/Getty ImagesThe moment a hyped-up new technology garners mainstream attention, many businesses will scramble to incorporate it into their enterprise. The majority of these trends will splutter and die out by Q4. Artificial intelligence (AI) is unlikely to be one of them.

AI is a transformative series of tools that can accelerate productivity, drive insight, and open up unexplored revenue streams. It’s poised to revolutionize the way we do business and everyone in a leadership role should be thinking about it.

But few organizations are set up to do AI properly.

There’s a common misconception that rebranding as an AI company is as simple as having data, infrastructure, and off-the-shelf data and analytics. The reality is that AI is complex, high-risk, expensive, and often requires significant business transformation. Most importantly, though, it demands an ultra-specialized talent pool that, according to latest reports, currently stands at only 22,000 PhD-level experts worldwide — a remarkably small pool.

When you consider that the annual market value predictions for AI techniques range between $3.5 trillion and $5.8 trillion, it’s clear why the battle to recruit from this scarce group has become the industry’s defining challenge. Right now, the biggest companies in the world are scooping up these experts to populate their teams because they understand that the key to building a robust, successful AI practice is to find and retain the right talent.

So, when the Royal Bank of Canada (RBC) approached me three years ago to help them grow their AI capabilities, this is what I advised: To go beyond data science and do real AI, you need to hire the right people, embrace research, and adapt your culture.

At the moment, AI is more of an open frontier than an industry-friendly space. Its applications are new enough that actual practitioners of AI don’t yet exist at scale. This makes finding, retaining, and nurturing talent the field’s most pressing challenge. If you want this capability in your organization, you have to hire the people with the perfect balance of data intuition and state-of-the-art knowledge. These people are almost all academics.

It’s impossible to overstate the importance of this expertise level. Machine learning models run on mathematics whose subtlety requires a deep understanding of data domains. Simple tasks can be daunting to those without the right experience. Mistakes in the machine learning space are extremely common, but when applied to business they can have real-life consequences too – up to and including life-and-death.

Here’s a textbook example of how easily these mistakes can occur. In 1973, the University of California at Berkeley compiled their graduate school admissions figures and discovered what appeared to be a significant bias against women applicants. The numbers were right there on the page: 44% of male applicants were admitted to graduate programs, versus 35% of female applicants.

Fearing a lawsuit, school officials shipped the data to their statistics department for a closer look. A team led by Peter Bickel, now the school’s professor emeritus of statistics, was able to decode the figures by parsing individual departments. When analyzed this way, the data didn’t provide evidence of bias; the issue was that women were applying to harder, more competitive programs with lower admission rates than their male counterparts. In fact, women had slightly higher admission rates than men per department. (This doesn’t mean there was no gender bias at play; it simply means the evidence that was being used to allege that bias – lower admissions rates for women – was not itself an indication of bias.)

Researchers will be familiar with this phenomenon, known as Simpson’s paradox. Machine learning challenges have significantly increased in complexity since then and it takes years of training and experience to develop a well-honed intuition that can sniff these problems out. In the case of Berkeley, the administration had access to an in-house team of top-flight statisticians. But it’s easy to see how inexperienced analysis could have tied the university up in a costly, lengthy legal battle. Instead, the university emerged with a more nuanced understanding of its admissions process.

In a knowledge-based economy, research becomes the means of production. This recognition should put an end to any misconception that as an AI-enabled business you can “get away” with not conducting in-house research. What leaders tend to miss here is that the scientific progress we’ve made in AI does not automatically render the technology ready for any environment. Each business carries its own unique challenges and requirements, from proprietary data types to operational constraints and compliance requirements, which may require additional customization and scientific progress.

This makes AI an extremely high-risk, high-return pursuit. To pursue research may, in this moment, seem like a novel and bold act. But it should be the norm. There is a vast competitive advantage that comes from owning these solutions for your industry. The companies that invest in research that adapts machine learning to their industry will generate extremely valuable intellectual property (IP).

One way to de-risk this pursuit is to pair fundamental research (pure science) and applied research practices together. The scientific pursuit is by definition open-ended: you can go on forever, pushing boundaries and conquering knowledge. (This is why universities will never go out of business.) Applied research, on the other hand, is designed to solve specific real-world problems. What applied researchers bring to the table is knowing when to stop researching and to focus on delivering a solution. Each practice serves to influence the other. It’s a simultaneous push forward that is less likely to end up with no payoff.

For instance, one of the areas we’re focused on at Borealis AI (the R&D arm of RBC) is natural language processing (NLP), the field of AI that can understand language. So far, NLP has proved most powerful for parsing and analyzing bodies of text in order to extract meaningful patterns. Our particular interest in this type of machine learning involves training NLP on news datasets to predict how global events can affect the trajectories of companies. The ultimate goal is to build software that can direct financial analysts in real-time toward relevant information within their respective industries.

It’s important to note that the state-of-the-art in machine learning has not yet reached the level where it can solve every aspect of this problem. NLP algorithms perform best in constrained environments, such as question and answer systems, where a user can ask a computer questions from a finite list of possible queries. Since the computer knows what to anticipate in language form, the program can respond accordingly.

But when the goal is to understand something as dynamic as news and apply that information to the relationship between companies and world events, it requires the ability to contextualize, then track the evolution of very complex and time-dependent entities. This is where the marriage between fundamental and applied research comes into play. In our case, fundamental research aims to advance NLP to a place where it can independently perform high-level language-based reasoning and grasp complex relationships at the same level as humans do. Our applied researchers then ensure these solutions can become immediately applicable to financial services. This is how we build products while pushing the boundaries of science.

The last step to building an AI practice is to create the right environment. The world is an AI researcher’s proverbial oyster right now. In an uncertain economy, they’re among the rare few whose opportunities continue to become more fruitful and multiply. Offering potential talent a dynamic, comfortable, and unique workspace is a good start. You also need to be able to offer compelling datasets and interesting problems to work on. Computational power and a strong team to provide research mentorship are also required. But the ability to pursue curiosity-driven research is the real draw.

When you hire from academia, you’re inviting a group of people into your organization who come from a very specific culture. They share values that are built on both the ethos of solving big, meaningful problems and having the ability to publish the results of their efforts. Researchers take pride in contributions they make, so these factors must be in place. This translates into reproducing some of the working conditions they’ve brought from academia while allowing the transparency of collaboration and open publication that serves to advance their community as a whole. Businesses working in closed environments need to reconsider that approach. If you are operating in this arena, it is up to you to prove your credentials and not the other way around.

Operating a business at the moment of this technological shift is a rare opportunity to seize upon an economic turning point. While we can’t yet predict how it will re-shape the market, the prevalence with which AI is already embedded into our core technologies favors early adoption.

Unlike the last industrial revolution, however, investing in big machinery won’t cut it. To truly have impact and remain relevant in the market, it’s up to executive leaders to build the bridge between research and commercialization. Only in this collaborative vein will AI’s true impact flourish.

How Your Identity Changes When You Change Jobs

Herminia Ibarra, a professor at the London Business School, argues that job transitions — even exciting ones that you’ve chosen — can come with all kinds of unexpected emotions. Going from a job that is known and helped define your identity to a new position brings all kinds of challenges. Ibarra says that it’s important to recognize how these changes are affecting you but to keep moving forward and even take the opportunity to reinvent yourself in your new role.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers