John A. Heldt's Blog, page 20

August 1, 2015

Review: The Finest Hours

As I noted in a review of Timothy Egan’s

The Big Burn

more than two years ago, I don’t read many non-fiction books. And, when I do, I tend to gravitate toward stories about disasters.

My latest venture into non-fiction was no exception. Last month I finished the audiobook of The Finest Hours . Written by Michael J. Tougias and Casey Sherman and narrated by Malcolm Hillgartner, it is the riveting account of the “U.S. Coast Guard’s most daring sea rescue” -- a historic event that I had never heard about.

The book is much more than a tale about the Pendleton and the Fort Mercer, two oil tankers that split in half in heavy seas off Massachusetts in February 1952. It is a tribute to an often overlooked and unappreciated branch of the U.S. military.

Tougias and Sherman tell the story from the perspective of the participants and, in doing so, give the reader a feel for what it was like to be there. The book is much like Sebastian Junger’s The Perfect Storm , which chronicled the last voyage of the doomed fishing boat Andrea Gail.

Like Junger’s work, Tougias and Sherman’s book will be adapted to the big screen. Walt Disney Pictures will release a film account of The Finest Hours in January.

I recommend the book for anyone who likes stories about the sea and about the unsung heroes of the Coast Guard who take risks that many of us could not even imagine. Rating: 4/5.

My latest venture into non-fiction was no exception. Last month I finished the audiobook of The Finest Hours . Written by Michael J. Tougias and Casey Sherman and narrated by Malcolm Hillgartner, it is the riveting account of the “U.S. Coast Guard’s most daring sea rescue” -- a historic event that I had never heard about.

The book is much more than a tale about the Pendleton and the Fort Mercer, two oil tankers that split in half in heavy seas off Massachusetts in February 1952. It is a tribute to an often overlooked and unappreciated branch of the U.S. military.

Tougias and Sherman tell the story from the perspective of the participants and, in doing so, give the reader a feel for what it was like to be there. The book is much like Sebastian Junger’s The Perfect Storm , which chronicled the last voyage of the doomed fishing boat Andrea Gail.

Like Junger’s work, Tougias and Sherman’s book will be adapted to the big screen. Walt Disney Pictures will release a film account of The Finest Hours in January.

I recommend the book for anyone who likes stories about the sea and about the unsung heroes of the Coast Guard who take risks that many of us could not even imagine. Rating: 4/5.

Published on August 01, 2015 07:10

July 28, 2015

Finding a place in Princeton

When you write historical fiction, you are immediately confronted with at least two challenges. The first is to describe a time. The second is to capture a place.

Writing about a time long before your own requires research. Writing about a place a thousand miles from home requires a visit. At least it does in my book. Literally.

Writing about a time long before your own requires research. Writing about a place a thousand miles from home requires a visit. At least it does in my book. Literally.

Though research can accomplish a lot, it is no substitute for an on-site inspection. I rediscovered that basic truth this week when I visited Princeton, New Jersey, the setting for Mercer Street, the second novel of the American Journey series.

I’m no stranger to college towns, particularly in the West. I’ve spent quality time in places like Eugene, Iowa City, Corvallis, Lafayette, Pullman, and Missoula. But nothing quite beats visiting a community with an Ivy League college.

I’m no stranger to college towns, particularly in the West. I’ve spent quality time in places like Eugene, Iowa City, Corvallis, Lafayette, Pullman, and Missoula. But nothing quite beats visiting a community with an Ivy League college.

For one thing, everything is old. Very old. Princeton, founded in 1683, is no exception. Whether on campus or off, it is not difficult to find a building that is at least two hundred years old. One, Nassau Hall, built in 1756, once housed the entire United States government.

Other buildings are younger but, for me, far more relevant. I went to Princeton to see what it might have looked like in 1938 and 1939, the setting of the book. And though much has obviously changed in eight decades, much has stayed the same.

I know this from comparing what I saw in books and online with what I saw in person. Georgian and Greek Revival houses still dominate plush residential neighborhoods. Albert Einstein’s last home, on Mercer Street, looks much as it did in the 1930s.

I know this from comparing what I saw in books and online with what I saw in person. Georgian and Greek Revival houses still dominate plush residential neighborhoods. Albert Einstein’s last home, on Mercer Street, looks much as it did in the 1930s.

As I did on earlier visits to Wallace, Idaho, and Galveston, Texas, the primary settings for The Fire and September Sky , I took notes, snapped photos, visited the local library, and tried to get a sense of place.

I think I succeeded -- or at least succeeded enough to proceed with the book. In Mercer Street, three women, representing three generations of the same family, travel from 2016 to 1938, where they find love, intrigue, and danger on the eve of World War II.

The novel is now in the draft stage and making its way through the first of many revisions. I still plan to publish by Thanksgiving.

Writing about a time long before your own requires research. Writing about a place a thousand miles from home requires a visit. At least it does in my book. Literally.

Writing about a time long before your own requires research. Writing about a place a thousand miles from home requires a visit. At least it does in my book. Literally.Though research can accomplish a lot, it is no substitute for an on-site inspection. I rediscovered that basic truth this week when I visited Princeton, New Jersey, the setting for Mercer Street, the second novel of the American Journey series.

I’m no stranger to college towns, particularly in the West. I’ve spent quality time in places like Eugene, Iowa City, Corvallis, Lafayette, Pullman, and Missoula. But nothing quite beats visiting a community with an Ivy League college.

I’m no stranger to college towns, particularly in the West. I’ve spent quality time in places like Eugene, Iowa City, Corvallis, Lafayette, Pullman, and Missoula. But nothing quite beats visiting a community with an Ivy League college.For one thing, everything is old. Very old. Princeton, founded in 1683, is no exception. Whether on campus or off, it is not difficult to find a building that is at least two hundred years old. One, Nassau Hall, built in 1756, once housed the entire United States government.

Other buildings are younger but, for me, far more relevant. I went to Princeton to see what it might have looked like in 1938 and 1939, the setting of the book. And though much has obviously changed in eight decades, much has stayed the same.

I know this from comparing what I saw in books and online with what I saw in person. Georgian and Greek Revival houses still dominate plush residential neighborhoods. Albert Einstein’s last home, on Mercer Street, looks much as it did in the 1930s.

I know this from comparing what I saw in books and online with what I saw in person. Georgian and Greek Revival houses still dominate plush residential neighborhoods. Albert Einstein’s last home, on Mercer Street, looks much as it did in the 1930s.As I did on earlier visits to Wallace, Idaho, and Galveston, Texas, the primary settings for The Fire and September Sky , I took notes, snapped photos, visited the local library, and tried to get a sense of place.

I think I succeeded -- or at least succeeded enough to proceed with the book. In Mercer Street, three women, representing three generations of the same family, travel from 2016 to 1938, where they find love, intrigue, and danger on the eve of World War II.

The novel is now in the draft stage and making its way through the first of many revisions. I still plan to publish by Thanksgiving.

Published on July 28, 2015 18:30

July 8, 2015

Giving animals their due

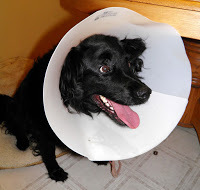

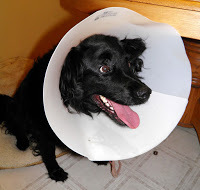

I admit I’m not very good at keeping track of these things. Had I not seen an obscure Internet reference yesterday, I would have never known that I had missed National Frog Month (April) and International Hug Your Cat Day (June 4) but could still participate in National Deaf Dog Awareness Week (September 20-26). My hard-of-hearing dog, Mocha (photo), has already circled the dates.

Groups create these observances because they love animals. So do many authors, including some who have turned stories about animals into celebrated works. These range from classics like

Charlotte’s Web

,

The Call of the Wild

, and

Black Beauty

to contemporary novels like

The Art of Racing in the Rain

.

Groups create these observances because they love animals. So do many authors, including some who have turned stories about animals into celebrated works. These range from classics like

Charlotte’s Web

,

The Call of the Wild

, and

Black Beauty

to contemporary novels like

The Art of Racing in the Rain

.

As an author of six novels, I haven't done much with four-legged friends. Max, a two-year-old Abyssinian cat, follows Joel Smith out a door in The Mine . In The Show , Grace Vandenberg gives a belly rub to a golden retriever named Killer. Kevin Johnson and Sadie Hawkins ride Spirit, a gentle Appaloosa, in Chapter 44 of The Fire .

Most other animals in my books are unnamed or unappreciated. When Justin Townsend spots a West Texas pronghorn from the window of a passenger train in September Sky , he admires it for a moment and then moves on to other things.

I plan to do better in the future. In the second book of the American Journey series, due this fall, a pork-chop-loving German shepherd named Fritz will play the part of a temperamental gatekeeper.

I recently finished the rough draft of that novel and sent it to my editor for a first read. That freed me up to do other things this month, such as properly recognize some toothy and misunderstood creatures. Shark Awareness Day is July 14.

Groups create these observances because they love animals. So do many authors, including some who have turned stories about animals into celebrated works. These range from classics like

Charlotte’s Web

,

The Call of the Wild

, and

Black Beauty

to contemporary novels like

The Art of Racing in the Rain

.

Groups create these observances because they love animals. So do many authors, including some who have turned stories about animals into celebrated works. These range from classics like

Charlotte’s Web

,

The Call of the Wild

, and

Black Beauty

to contemporary novels like

The Art of Racing in the Rain

.As an author of six novels, I haven't done much with four-legged friends. Max, a two-year-old Abyssinian cat, follows Joel Smith out a door in The Mine . In The Show , Grace Vandenberg gives a belly rub to a golden retriever named Killer. Kevin Johnson and Sadie Hawkins ride Spirit, a gentle Appaloosa, in Chapter 44 of The Fire .

Most other animals in my books are unnamed or unappreciated. When Justin Townsend spots a West Texas pronghorn from the window of a passenger train in September Sky , he admires it for a moment and then moves on to other things.

I plan to do better in the future. In the second book of the American Journey series, due this fall, a pork-chop-loving German shepherd named Fritz will play the part of a temperamental gatekeeper.

I recently finished the rough draft of that novel and sent it to my editor for a first read. That freed me up to do other things this month, such as properly recognize some toothy and misunderstood creatures. Shark Awareness Day is July 14.

Published on July 08, 2015 19:25

June 9, 2015

Book Seven: A midterm report

Of all the rules Stephen King has laid down for writers, none gets my attention like this one:

"You have three months."

That’s not three months to create an outline or write a prologue but rather three months to complete an entire first draft. Whether the book is 30,000 words or 300,000 makes no difference.

Three months.

Last week, I began month three in my quest to write book seven. I am now more than 72,000 words and fifty chapters into a novel that I hope will be my best.

Along the way, I’ve learned a few things. I’ve learned a lot about 1938, 1939, and Princeton, New Jersey, the setting of the novel, and even more about a central truth of fiction.

You don’t control the story or the characters. They control you.

When I outlined the second novel of the American Journey series in March, I had a time-travel romance in mind. What has emerged is a more sophisticated work, a book that takes a few risks and views two critical years from a fresh perspective.

I probably won't beat King’s ninety-day deadline. There are lawns to mow, fish to catch, vacations to take, and a summer to enjoy. But I probably will come close.

I hope to have that all-important first draft out by the third week of July. I expect to publish by Thanksgiving.

"You have three months."

That’s not three months to create an outline or write a prologue but rather three months to complete an entire first draft. Whether the book is 30,000 words or 300,000 makes no difference.

Three months.

Last week, I began month three in my quest to write book seven. I am now more than 72,000 words and fifty chapters into a novel that I hope will be my best.

Along the way, I’ve learned a few things. I’ve learned a lot about 1938, 1939, and Princeton, New Jersey, the setting of the novel, and even more about a central truth of fiction.

You don’t control the story or the characters. They control you.

When I outlined the second novel of the American Journey series in March, I had a time-travel romance in mind. What has emerged is a more sophisticated work, a book that takes a few risks and views two critical years from a fresh perspective.

I probably won't beat King’s ninety-day deadline. There are lawns to mow, fish to catch, vacations to take, and a summer to enjoy. But I probably will come close.

I hope to have that all-important first draft out by the third week of July. I expect to publish by Thanksgiving.

Published on June 09, 2015 12:58

May 8, 2015

Breaking through the 'block'

Oxford defines writer’s block as "the condition of being unable to think of what to write or how to proceed with writing."

It is a malady that torments many writers, challenges most, and prompts others to deny its very existence. It also inspires some to provide creative remedies.

I investigated some of these remedies today after reaching a point in the second American Journey book that demanded at least a pause. The pop-culture site Flavorwire compiled advice from more than a dozen famous writers.

Most of the writers advised doing something specific, such as taking a walk or making a pie (Hilary Mantel) or writing "the cat sat on the mat, that is that, not a rat" for two weeks (Maya Angelou).

Mark Twain suggested breaking "complex overwhelming tasks into small manageable tasks, and then starting on the first one."

I have found one of Mantel’s approaches useful. When I reach a dead-end point in the writing process, I take a walk — a long walk in a natural setting, away from noise and electronic distractions.

Like Twain, I also break the complex into the manageable. I will often set up a scene on Tuesday, describe it on Wednesday, and revise it the next week. When tackling complex parts of a novel, I’ve discovered that two (or three) chapters are better than one.

I am currently seventeen chapters into my latest work, a tale about a grandmother, daughter, and granddaughter who venture back to New Jersey on the eve of World War II. I am making good progress and expect to complete a first draft by the end of August.

With or without writer’s block.

It is a malady that torments many writers, challenges most, and prompts others to deny its very existence. It also inspires some to provide creative remedies.

I investigated some of these remedies today after reaching a point in the second American Journey book that demanded at least a pause. The pop-culture site Flavorwire compiled advice from more than a dozen famous writers.

Most of the writers advised doing something specific, such as taking a walk or making a pie (Hilary Mantel) or writing "the cat sat on the mat, that is that, not a rat" for two weeks (Maya Angelou).

Mark Twain suggested breaking "complex overwhelming tasks into small manageable tasks, and then starting on the first one."

I have found one of Mantel’s approaches useful. When I reach a dead-end point in the writing process, I take a walk — a long walk in a natural setting, away from noise and electronic distractions.

Like Twain, I also break the complex into the manageable. I will often set up a scene on Tuesday, describe it on Wednesday, and revise it the next week. When tackling complex parts of a novel, I’ve discovered that two (or three) chapters are better than one.

I am currently seventeen chapters into my latest work, a tale about a grandmother, daughter, and granddaughter who venture back to New Jersey on the eve of World War II. I am making good progress and expect to complete a first draft by the end of August.

With or without writer’s block.

Published on May 08, 2015 09:15

April 9, 2015

Review: Second Honeymoon

There was a time when I went through James Patterson novels like some people go through newspapers. In a stretch of five years, I read thirty-four Patterson books. This past week, I read — or rather listened to — Number 35. Like those that preceded it,

Second Honeymoon

was worth the time and effort.

In the 2013 thriller, co-written by Howard Roughan, FBI agents John O’Hara and Sarah Brubaker hunt two serial killers, including one who targets honeymooners. As with many Patterson novels, this one features romance, intrigue, and enough twists to make even a detail-oriented reader like me pay close attention.

Listening to the downloadable audiobook was an experience in itself. Music, sound effects, and the alternating voices of readers Jay Snyder and Ellen Archer gave the work a “radio mystery” feel.

I thought Snyder and Archer did a fair job and found their presentation preferable to the standard single-reader approach. Few readers, in my opinion, have the range to convincingly represent characters of both genders.

As for the novel itself, I liked it. I didn't care for the numerous cliches, product name-dropping, and occasionally silly dialogue, but I did like the story. Patterson is still the king of suspense. If nothing else, he gave me a reason to read Book 36. Rating: 3/5.

In the 2013 thriller, co-written by Howard Roughan, FBI agents John O’Hara and Sarah Brubaker hunt two serial killers, including one who targets honeymooners. As with many Patterson novels, this one features romance, intrigue, and enough twists to make even a detail-oriented reader like me pay close attention.

Listening to the downloadable audiobook was an experience in itself. Music, sound effects, and the alternating voices of readers Jay Snyder and Ellen Archer gave the work a “radio mystery” feel.

I thought Snyder and Archer did a fair job and found their presentation preferable to the standard single-reader approach. Few readers, in my opinion, have the range to convincingly represent characters of both genders.

As for the novel itself, I liked it. I didn't care for the numerous cliches, product name-dropping, and occasionally silly dialogue, but I did like the story. Patterson is still the king of suspense. If nothing else, he gave me a reason to read Book 36. Rating: 3/5.

Published on April 09, 2015 08:16

March 2, 2015

My go-to place for info

I have sought its assistance when writing every book.

When preparing The Mine and The Mirror , I asked it for information on the peacetime military draft in 1941 and 1964.

When researching The Fire , I inquired about the price of pearls in 1907, public reaction to Halley's comet in 1910, the workings of the National Forest Service, and the incubation period for polio.

When planning September Sky , I requested turn-of-the-last-century fire insurance maps of Galveston, write-ups on Pullman porters, and a primer on U.S. copyright law.

The Library of Congress delivered every time.

It delivered again last week. Mere days after I requested news articles on the cherry blossom festival in Washington, D.C, in 1939, the LOC sent two Washington Post stories directly to my in-box.

I expect that these articles and others will prove useful when I write the second novel in the American Journey series later this year.

I point all this out not only to praise the LOC — a national treasure if there was one — but also to draw attention to libraries in general.

In today’s digital world, where information can be obtained and shared with lightning speed, many believe that libraries are not necessary. They believe they are obsolete and needlessly expensive. As a result, many of these institutions for forced to scrap for funds and continually justify their existence.

As a former reference librarian who knows the difference between the first answer from a search engine and the best answer from a book, I hope this kind of thinking passes. A strong society depends on information that is not only timely but also accurate, relevant, and accessible. It needs information that is free.

As an author of historical fiction, I can’t count on life experience to fill every void or answer every question in a novel. I must depend on others to provide facts, materials, and guidance.

Libraries, including that treasure in the nation’s capital, continue to do just that. For that reason alone, I will always have their back.

When preparing The Mine and The Mirror , I asked it for information on the peacetime military draft in 1941 and 1964.

When researching The Fire , I inquired about the price of pearls in 1907, public reaction to Halley's comet in 1910, the workings of the National Forest Service, and the incubation period for polio.

When planning September Sky , I requested turn-of-the-last-century fire insurance maps of Galveston, write-ups on Pullman porters, and a primer on U.S. copyright law.

The Library of Congress delivered every time.

It delivered again last week. Mere days after I requested news articles on the cherry blossom festival in Washington, D.C, in 1939, the LOC sent two Washington Post stories directly to my in-box.

I expect that these articles and others will prove useful when I write the second novel in the American Journey series later this year.

I point all this out not only to praise the LOC — a national treasure if there was one — but also to draw attention to libraries in general.

In today’s digital world, where information can be obtained and shared with lightning speed, many believe that libraries are not necessary. They believe they are obsolete and needlessly expensive. As a result, many of these institutions for forced to scrap for funds and continually justify their existence.

As a former reference librarian who knows the difference between the first answer from a search engine and the best answer from a book, I hope this kind of thinking passes. A strong society depends on information that is not only timely but also accurate, relevant, and accessible. It needs information that is free.

As an author of historical fiction, I can’t count on life experience to fill every void or answer every question in a novel. I must depend on others to provide facts, materials, and guidance.

Libraries, including that treasure in the nation’s capital, continue to do just that. For that reason alone, I will always have their back.

Published on March 02, 2015 17:56

February 18, 2015

Review: Winter of the World

To say that Ken Follett is one of my favorite authors is a serious understatement. I have read eighteen of his novels, including four of his massive historical tomes, and loved them all.

I still consider The Pillars of the Earth, Follett’s epic about twelfth-century England, to be the best book I have ever read. So I didn’t need much incentive to return to his works when I finally had the chance to do so.

This time the treat of choice was Winter of the World, the second book of the Century Trilogy. The series includes Fall of Giants, which I read following its release in 2010, and Edge of Eternity, which I will devour at the earliest opportunity.

Winter follows the lives of five interrelated families — English, Welsh, Russian, German, and American — from the rise of the Third Reich in 1933 through the beginnings of the Cold War in 1949. Though there are far too many characters to name in a single review, there were not too many to leave an impression.

Follett tells the story of the time from several perspectives: young and old, male and female, rich and poor, civilian and military, and good and evil. He gives readers a front-row seat of the Spanish Civil War, Pearl Harbor, Midway, D-Day, the development of atomic weapons, and the political drama in Britain, Germany, and the U.S. Few stones from the era are left unturned.

Though I gravitated toward the riveting descriptions of major historical events, I also loved the many personal narratives. I became quickly invested in Lloyd Williams, the principled and daring English soldier; Daisy Peshkov, the plucky American socialite; and Carla von Ulrich, the young German nurse who gave new meaning to courage and sacrifice.

In Winter of the World, Follett doesn’t make readers choose between big-picture history and small. He gives us both — and a whole lot more. I look forward to completing the trilogy and returning to the author's earlier works. It’s time to catch up. Rating: 5/5.

I still consider The Pillars of the Earth, Follett’s epic about twelfth-century England, to be the best book I have ever read. So I didn’t need much incentive to return to his works when I finally had the chance to do so.

This time the treat of choice was Winter of the World, the second book of the Century Trilogy. The series includes Fall of Giants, which I read following its release in 2010, and Edge of Eternity, which I will devour at the earliest opportunity.

Winter follows the lives of five interrelated families — English, Welsh, Russian, German, and American — from the rise of the Third Reich in 1933 through the beginnings of the Cold War in 1949. Though there are far too many characters to name in a single review, there were not too many to leave an impression.

Follett tells the story of the time from several perspectives: young and old, male and female, rich and poor, civilian and military, and good and evil. He gives readers a front-row seat of the Spanish Civil War, Pearl Harbor, Midway, D-Day, the development of atomic weapons, and the political drama in Britain, Germany, and the U.S. Few stones from the era are left unturned.

Though I gravitated toward the riveting descriptions of major historical events, I also loved the many personal narratives. I became quickly invested in Lloyd Williams, the principled and daring English soldier; Daisy Peshkov, the plucky American socialite; and Carla von Ulrich, the young German nurse who gave new meaning to courage and sacrifice.

In Winter of the World, Follett doesn’t make readers choose between big-picture history and small. He gives us both — and a whole lot more. I look forward to completing the trilogy and returning to the author's earlier works. It’s time to catch up. Rating: 5/5.

Published on February 18, 2015 20:10

February 1, 2015

A plotter, not a pantser

E.L. Doctorow once said, “Writing is like driving at night in the fog. You can only see as far as your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way.”

I must say that, for the most part, I can’t relate. When it comes to producing novels, I'm a "plotter" and not a "pantser." A pantser is someone who writes by the seat of his (or her) pants -- a person who can reach a destination without looking too far ahead.

Writing for me is not a spontaneous process that begins by opening a blank page on my laptop. It is a process that is so clear and ordered, it’s like driving all day in sunshine on a flat, straight, traffic-free highway with my GPS navigator activated.

My outline takes the form of detailed chapter summaries that can run from twenty words to two hundred. If there’s something I want to mention in Chapter 26, I’ll leave myself a reminder. Often I will add entire quotes or passages to a summary.

By the time I’m ready to start Chapter 1, I know not only which roads I will take to get to my destination but also which ones I’ll avoid. Virtually every twist, turn, and potential obstacle will be identified well in advance.

I say virtually because, like most authors, I like to leave some room to depart from the script and do something entirely different.

When I wrote The Mine , my first novel, I added a Japanese-American character about a third of the way in. The character, a college senior named Katie, became one of the most instrumental figures in the book. In three other novels, I added two lengthy chapters after the first draft was “finished.”

I’ve found that this approach works well. By outlining a novel in advance, I reduce the chances of writing myself into a corner. By leaving myself wiggle room, I leave open the possibility of heading down a better road.

In the twentieth of his twenty-two lessons on writing, Stephen King advises writers to take a break from their finished draft. He suggests six weeks, in fact, so that they can return to their manuscript with fresh eyes and see the proverbial forest among the trees.

I think this is sound advice. Good writing is a process that requires not only discipline and perseverance but also patience and perspective. What may seem a great idea in the planning stages may seem downright dumb in the end.

As I jump into the second novel of my second series, I plan to drive during the day with a map handy. But I’m going to keep an eye on the signs. Last-minute detours can to more than make a trip more interesting. They can make it better.

I must say that, for the most part, I can’t relate. When it comes to producing novels, I'm a "plotter" and not a "pantser." A pantser is someone who writes by the seat of his (or her) pants -- a person who can reach a destination without looking too far ahead.

Writing for me is not a spontaneous process that begins by opening a blank page on my laptop. It is a process that is so clear and ordered, it’s like driving all day in sunshine on a flat, straight, traffic-free highway with my GPS navigator activated.

My outline takes the form of detailed chapter summaries that can run from twenty words to two hundred. If there’s something I want to mention in Chapter 26, I’ll leave myself a reminder. Often I will add entire quotes or passages to a summary.

By the time I’m ready to start Chapter 1, I know not only which roads I will take to get to my destination but also which ones I’ll avoid. Virtually every twist, turn, and potential obstacle will be identified well in advance.

I say virtually because, like most authors, I like to leave some room to depart from the script and do something entirely different.

When I wrote The Mine , my first novel, I added a Japanese-American character about a third of the way in. The character, a college senior named Katie, became one of the most instrumental figures in the book. In three other novels, I added two lengthy chapters after the first draft was “finished.”

I’ve found that this approach works well. By outlining a novel in advance, I reduce the chances of writing myself into a corner. By leaving myself wiggle room, I leave open the possibility of heading down a better road.

In the twentieth of his twenty-two lessons on writing, Stephen King advises writers to take a break from their finished draft. He suggests six weeks, in fact, so that they can return to their manuscript with fresh eyes and see the proverbial forest among the trees.

I think this is sound advice. Good writing is a process that requires not only discipline and perseverance but also patience and perspective. What may seem a great idea in the planning stages may seem downright dumb in the end.

As I jump into the second novel of my second series, I plan to drive during the day with a map handy. But I’m going to keep an eye on the signs. Last-minute detours can to more than make a trip more interesting. They can make it better.

Published on February 01, 2015 08:02

January 25, 2015

Review: The English Girl

A few years ago, before I began writing novels of my own, I used to jump on every thriller that hit the bestsellers list. Vince Flynn became a fast favorite, as did James Patterson, Joel Rosenberg, Lincoln Child, and Tess Gerritsen. But only Flynn captured my attention like Daniel Silva.

This month I returned to Silva by reading The English Girl and found it every bit as riveting as The Messenger, Moscow Rules, and The Rembrandt Affair. Centered around Israeli intelligence officer Gabriel Allon, the novel, Silva’s sixteenth, is perhaps his best.

When the English girl in question, the mistress of the prime minister, goes missing in Corsica, Allon is called in by his British counterpart to assist with her return. Before long, he finds himself racing around France and Britain to beat a seven-day deadline imposed by the victim’s abductors.

As in his earlier books, Silva weaves a tale that is both intricate and straightforward. Old friends and adversaries meet in familiar places to resolve a mystery that kept me on edge almost to the very end.

Silva also takes an extra step in humanizing his sometimes colorless and mechanical protagonist. We see Allon not only as a master spy but also as a friend and a family man.

Though sometimes drawn-out, particularly in the middle, the book held my interest throughout. I am glad to see that Silva has not lost his touch and look forward to reading his latest work. Rating: 4/5.

This month I returned to Silva by reading The English Girl and found it every bit as riveting as The Messenger, Moscow Rules, and The Rembrandt Affair. Centered around Israeli intelligence officer Gabriel Allon, the novel, Silva’s sixteenth, is perhaps his best.

When the English girl in question, the mistress of the prime minister, goes missing in Corsica, Allon is called in by his British counterpart to assist with her return. Before long, he finds himself racing around France and Britain to beat a seven-day deadline imposed by the victim’s abductors.

As in his earlier books, Silva weaves a tale that is both intricate and straightforward. Old friends and adversaries meet in familiar places to resolve a mystery that kept me on edge almost to the very end.

Silva also takes an extra step in humanizing his sometimes colorless and mechanical protagonist. We see Allon not only as a master spy but also as a friend and a family man.

Though sometimes drawn-out, particularly in the middle, the book held my interest throughout. I am glad to see that Silva has not lost his touch and look forward to reading his latest work. Rating: 4/5.

Published on January 25, 2015 09:56