Chiara C. Rizzarda's Blog, page 27

September 23, 2024

SAFe, LeSS and DAD

I don’t know who picks acronyms for Agile frameworks, but I know I’d like to keep my distance from them.

Anyway, in my effort to propose methods and techniques that aren’t old enough to drink, today I’d like to show you these three frameworks, all born around 2011.

What do they have in common?They’re all trying to scale up and discipline Agile, which might be counterintuitive but addresses two of the main concerns in adopting the method:

“My Project is Just Too Big and Complex and Projecty For Your Puny Tools” (even if we saw that Agile is born in situations where waterfall was failing because the project was… well… too big and complex, this concern often comes from the project manager’s own sense of superiority);“People Who Aren’t Controlled Do Not Work” (see above).Regardless of my personal criticism towards the attitude, the frameworks have merit, so let’s see them one by one.

The Frameworks1. Scaled Agile Framework (SAFe)The Scaled Agile Framework (SAFe) is a structured approach designed to help large organizations implement Agile practices across multiple teams and departments. It was developed to address the challenges of scaling Agile methodologies beyond individual teams, promoting alignment, collaboration, and delivery across large numbers of groups.

SAFe was introduced in 2011 by Dean Leffingwell, a software development methodologist, and Drew Jemilo, an executive-level enterprise consultant and now retired co-founder. It evolved from Leffingwell’s earlier work resulting in The Agile Enterprise Big Picture, a chart which aimed to provide a comprehensive view of how Agile practices could be integrated into larger organizational structures. Since its inception, SAFe has undergone several revisions, with the latest version, SAFe 6.0, released in March 2023. The framework has gained widespread adoption across various industries, including software development, finance, and healthcare, becoming one of the most popular frameworks for scaling Agile practices.

Version 3 of the Big Picture.

Version 3 of the Big Picture.SAFe operates at three primary levels:

Team Level: individual Agile teams work using frameworks like Scrum or Kanban;Program Level: multiple teams collaborate on larger initiatives, coordinated through an Agile Release Train (ART);Portfolio Level: aligning strategy and execution, managing investments and ensuring that initiatives align with business goals.The Agile Release Train (ART) is a key component of SAFe, where multiple Agile teams work together to deliver value in a synchronized manner. ARTs typically operate on a fixed schedule, delivering increments of value every few weeks. To do so, it introduces various roles, such as Release Train Engineer, Product Manager, and System Architect, which help define responsibilities at different organizational levels.

Specifically, an Agile Release Train is essentially a long-lived, self-organizing team of Agile teams, typically consisting of 50 to 125 individuals. These teams collaborate to develop, deliver, and often operate one or more solutions within a defined value stream. The ART operates on a fixed schedule, delivering incremental value through a series of Program Increments (PIs), which are time-boxed periods typically lasting 8 to 12 weeks.

ARTs are composed of cross-functional teams that encompass all the necessary skills and expertise required to define, build, test, and deliver solutions. This cross-functional structure not only promotes collaboration but also minimizes dependencies between teams, fostering a more seamless workflow. One of the defining features of an ART, however, is the alignment around a common vision and set of goals. All teams within the ART share a unified Program Backlog and strategic objectives, ensuring that their collective efforts are directed toward achieving the same overarching goals. This alignment is crucial for maintaining focus and cohesion across the teams.

Operating on a fixed cadence provides a predictable schedule for delivering increments of work. This regular cadence helps synchronize the activities of multiple teams, facilitating systematic planning and execution. Key roles within the ART play vital roles in ensuring the success of this process. The Release Train Engineer (RTE) serves as a servant leader, facilitating ART events, managing dependencies, and driving continuous improvement across the teams. The Product Manager is responsible for defining the vision and prioritizing the features within the Program Backlog, ensuring that the most valuable work is being addressed. The System Architect oversees the architectural integrity of the solution, ensuring that both functional and non-functional requirements are met. Business Owners, who are key stakeholders, hold accountability for the business outcomes of the ART.

A critical component of ARTs is Program Increment (PI) Planning, a collaborative event at the start of each PI where teams come together to define objectives and commit to delivering specific features. This planning event fosters collaboration, provides clarity on priorities, and aligns the teams on what needs to be achieved.

Implementing an ART involves:

Identifying Value Streams: as usual, the first step is to identify the value streams within the organization that the ART will focus on;Launching the ART: this includes assembling the teams, defining roles, and conducting initial training on SAFe principles;Executing Program Increments: teams work together to deliver features during the PI, with regular checkpoints to assess progress and adjust plans as needed;Continuous Feedback and Adaptation: after each PI, teams reflect on their work and make adjustments to improve future performance.Continuous improvement is a foundational principle of ARTs. Regular retrospectives and inspect-and-adapt sessions are conducted to evaluate performance, identify areas for improvement, and ensure that the ART continually evolves and adapts to changing needs. This commitment to continuous improvement helps ARTs maintain high levels of performance and effectiveness over time.

The latest versions of SAFe emphasize the importance of business agility, encouraging organizations to respond quickly to changing market conditions and customer needs. It can be tailored to different organizational needs through four configurations:

Essential SAFe: the foundational elements necessary for successful implementation;Large Solution SAFe: for managing complex solutions that require coordination across multiple ARTs;Portfolio SAFe: aligning strategy with execution at the portfolio level;Full SAFe: integrating all aspects of the framework for comprehensive scaling.2. Large Scale Scrum (LeSS)As you know if you’ve been following me throughout the years, Scrum is possibly my favourite Agile framework, and I have talked about it multiple times.

Large Scale Scrum (LeSS) is a again framework designed to extend the principles of Scrum to multiple teams working on a single product. It aims to maintain the simplicity and effectiveness of Scrum while addressing the complexities that arise when scaling Agile practices across larger organizations.

LeSS was developed by Craig Larman and Bas Vodde in 2005 while they were working at Nokia Siemens Networks (so yeah, at least in Europe it’s old enough to drink). They sought to apply Agile and Scrum methodologies to large, multi-site product development environments. Over time, they refined their approach and published their findings in the book Large-Scale Scrum: More with LeSS, which outlines the framework’s principles, practices, and guidelines.

LeSS emphasizes a “barely sufficient” framework, meaning it aims to reduce complexity and overhead while retaining the core elements of Scrum. This approach encourages teams to focus on delivering value and trim unnecessary bureaucratic processes.

One of the key differentiators in LeSS is the use of a joint Product Owner for the entire group of teams. Unlike traditional Scrum, where each team might have its own Product Owner, LeSS employs a single Product Owner to ensure a unified vision and consistent prioritization across all teams. This centralized role helps to maintain a clear direction and alignment with the overall product goals.

LeSS also emphasizes the importance of cross-functional teams. In this structure, teams are equipped with all the necessary skills to deliver a complete product increment, we minimize dependencies between teams and enhance collaboration, enabling teams to work more efficiently and independently.

The sprint planning and review processes in LeSS are adapted to support large-scale efforts. Sprint planning begins with a group-wide planning meeting, where all teams gather to discuss the overarching goals and strategy for the sprint. This is followed by individual team planning sessions, allowing each team to detail its specific tasks and contributions. Sprint reviews in LeSS involve all teams and stakeholders, promoting transparency and enabling collective feedback, which is essential for continuous improvement. Retrospectives, however, go beyond the team level and encourage an overall review at the end of each sprint. This group-wide retrospective focuses on identifying improvements for the entire group rather than just individual teams. This is a way to foster a culture of continuous improvement and shared growth, ensuring that the organization as a whole can evolve and adapt more effectively.

LeSS is guided by ten principles that inform decision-making and practices within the framework:

Large-Scale Scrum is Scrum, as opposed to the “Scrum But” principle stating that, when you make exceptions or modifications that deviate from the core principles and practices of Scrum, you’re losing value altogether;Empirical process control;Transparency;More with less, emphasising the idea that complex product development does not require complex solutions;Whole product focus;Customer-centric approach;Continuous improvement towards perfection;Systems thinking;Lean thinking;Queuing theory stating that, especially in software development, we often build up invisible queues, such as requirements documents, untested code, or features waiting for integration, and these queues can significantly increase cycle times and introduce delays.3. Disciplined Agile Delivery (DAD)Disciplined Agile Delivery (DAD) is a hybrid Agile framework that provides guidance to optimize the delivery process. It was created by Scott Ambler and Mark Lines, with its foundational concepts first introduced in Ambler’s 2013 white paper, “Going Beyond Scrum: Disciplined Agile Delivery.” This paper laid the groundwork for a more flexible and comprehensive approach to Agile, one that could adapt to a variety of project types and organizational needs.

The primary reference for understanding and implementing DAD, however, is the subsequent book Choose Your WoW! by Ambler and Lines, with the acronym standing for Way of Working. This book serves as a detailed guide for Agile practitioners, offering a toolkit of practices and strategies to tailor Agile methodologies to specific project contexts. The Project Management Institute (PMI) acquired the rights to the framework in 2019 as a part of PMI’s broader strategy to get their hands on Agile and provide project managers with a set of tools that wasn’t covered in mold.

DAD is based on eight core principles, some of which are taken from the Agile manifesto:

People-first: people and interactions are the primary determinants of success;Goal-driven: production should focus on clear goals and outcomes;Hybrid Agile: practices are chosen from various Agile frameworks and methodologies;Learning-oriented: continuous learning and improvement are emphasized;Full delivery lifecycles: address the entire delivery lifecycle from ideation to deployment;Solution-focused: deliver consumable solutions, not just finished products;Risk-value lifecycle: explicitly manage risk and value;Enterprise aware: understand the organizational context and dependencies.One of the distinguishing features of DAD is its support for multiple lifecycles. Depending on the nature of the project, teams can choose from six different lifecycles: Agile, Lean, Continuous Delivery, Exploratory, and specialized versions for large teams. This adaptability allows teams to select the most appropriate lifecycle for their project’s goals and constraints.

The Frameworks comparedWhile all three frameworks share the common goal of scaling Agile practices to meet the needs of larger organizations with multiple teams and incorporate principles from Lean and Agile methodologies, they get there proposing significantly different structures, prescriptives, focuses across the project lifecycle, and adoption patterns.

SAFe is known for its structured and prescriptive nature. It provides detailed roles, ceremonies, and artifacts that are designed to coordinate work across multiple teams, making it particularly appealing to large enterprises that are looking for a clear, comprehensive roadmap to guide their Agile transformation. In contrast, LeSS emphasizes simplicity and transparency. It retains the core practices of Scrum while adapting them for larger, multi-team environments. LeSS is ideal for organizations that prioritize simplicity and wish to stay closely aligned with Scrum’s original principles, even as they scale. DAD, on the other hand, takes a more flexible, context-driven approach. It allows teams to tailor Agile practices based on their unique needs, making it particularly well-suited for organizations that require a customized approach to Agile, depending on the specific demands of their projects and teams.

When it comes to lifecycle focus, SAFe extends its influence beyond just the team level, focusing on the program and portfolio levels to align strategic objectives with execution. This ensures that work at the team level is closely connected to broader business goals. LeSS, in contrast, focuses on scaling Scrum across multiple teams while maintaining a single Product Owner and Product Backlog, preserving the integrity of Scrum practices even in a larger context. DAD takes a comprehensive view, addressing the entire delivery lifecycle from ideation to deployment. It includes aspects like solution architecture and portfolio management, making it suitable for organizations that need to consider the full spectrum of delivery, not just team-level practices.

In terms of adoption, SAFe is the most widely adopted framework, especially among large enterprises that benefit from its structured approach and extensive guidance. LeSS tends to be better suited for organizations with a strong Agile foundation that prefer simplicity and decentralization. Its focus on maintaining core Scrum principles appeals to those looking to scale without losing the essence of Scrum. DAD, due to its need for customization, is particularly valuable for organizations undergoing traditional-to-Agile transitions or those managing complex projects. However, this customization often requires experienced consultants to tailor the framework to specific organizational contexts, particularly in large projects.

September 22, 2024

Endogenous vs. Exogenous Thinking in Organisational Improvisation

The theory of Organizational Improvisation focuses on responsive processes and how understanding them provides an alternative to the idea of an opposition between “strong” (endogenous) and “weak” (exogenous) ways of thinking about processes in human action.

This dichotomy originally related to how actions are initiated and controlled and stemmed from cognitive psychology and neuroscience:

Strong (Endogenous) Thinking is considered internally driven, meaning that actions are guided by internal plans, intentions, or goals. This type of thinking emphasizes the role of cognitive processes in determining behavior, suggesting that individuals actively construct their actions based on internal representations and decisions. In the context of attention, strong endogenous control is characterized by sustained attention that is maintained through effortful cognitive processes, which can be influenced by factors such as motivation and task relevance, and its characteristics are:Being Goal-Oriented: actions are based on personal goals and intentions;Involving Controlled Processing and higher cognitive functions such as planning, decision-making, and self-regulation;Flexibility: it allows for adaptation to changing circumstances based on internal assessments.Weak (Exogenous) Thinking is externally driven, where actions are influenced by external stimuli in the environment. This perspective suggests that behavior can be automatically triggered by external cues, often bypassing conscious thought. In terms of attention, weak exogenous control refers to how individuals can be drawn to stimuli in their environment, often leading to quick shifts in focus that are not necessarily aligned with their current goals. Its characteristics are:Being Stimulus-Driven: actions are initiated in response to external events or cues, often without deliberate intention;Involving Automatic Processing and reflexive responses to stimuli, which can happen rapidly and unconsciously;Limited Control: actions may not be easily altered by internal goals or plans once triggered by external factors.In cognitive sciences, Daniel Kahneman expressed this concept by talking about slow and fast thinking, and the whole apparatus is rooted in Kant and his idea that humans gain knowledge of phenomena via the scientific method, acting as objective observers who formulate and test hypotheses. This involves taking an objective observer’s stance, formulating hypotheses, and testing them experimentally, and laying one’s belief in two fundamental assumptions:

Human action follows rationalist causality;Nature follows either efficient or formative causality.Kant described a system as a self-organizing entity where parts interact to create both themselves and the whole, developing over time in a purposive sequence from embryonic to mature stages, driven by formative causality.

Hegel argued fiercely against Kant’s dualisms and developed a notion of deeply social human processes involving the interaction of humans in responsive processes of struggling for mutual recognition as participants.

Come to San Diego, and you’ll see where I stand.

September 21, 2024

Organisational Improvisation

One of the key topics of my upcoming class at Autodesk University revolves around Organisational Improvisation. I already talked about it on the blog here, back from the 2021 International LEGO Serious Play Conference in Billund, but today’s let’s dive a bit into the concept, its origin and why is it relevant for planning.

When it comes to dealing with the unexpected, one can’t address the subject without mentioning Dr. Lukas Zenk, associated professor at the Danube University of Krems and co-founder of the Organizational Improvisation project which deals specifically with how to “help experts think on their feet.”

“We live in a world that is currently undergoing major changes,” argues Zenk and his team. “Many of our previous plans can no longer continue in this form, and we are faced with the challenge of acting in the here and now. Improvisation means dealing with the unforeseen (“improvisus” – the unforeseen).” In this context, improvisation is about being able to roll with different inputs in an unplanned situation, planning and acting at the same time.

“Organizational Improvisation” is an applied research project where the group of studies investigated the mindset and skills of experts in the arts, science, and business – and research on improvisation as a general behaviour – with the aim to better understand the ability to improvise in different contexts, including improvisational theatre, jazz, creativity and innovation, entrepreneurship, as well as emergency forces. The approach is similar to how Csikszentmihalyi worked while developing the flow theory, rooted in a fascination with the psychological states of artists and athletes who became deeply immersed in their activities and involving extensive qualitative research, including interviews and observations of individuals across various fields to understand their optimal experiences and the conditions that fostered such states.

I’m sure you’ve heard about it: people are “in the flow” when there’s a correct balance between the challenge level and their perceived skills.

I’m sure you’ve heard about it: people are “in the flow” when there’s a correct balance between the challenge level and their perceived skills.But the concept of Improvisation goes way beyond the individual. As Ralph.D. Stacey and Chris Mowles articulate in their masterpiece on Strategic Management and Organizational Dynamics, a new method of scientific modeling of organizations, known as cellular automata within a field called the natural complexity sciences, has been developed throughout the last 50 years of the 21st Century. In these models, the basic interaction rules followed by each part of a larger system, like a coral polyp in a coral reef, are simulated on a computer to observe the global patterns.

This modeling approach helps tackle large-scale problems with many interacting components, showing that complex global patterns can emerge from local interactions without any centralized control or global design principles. The complexity seen in species behavior is generated by simple, repeated local interactions of base units, leading to emergent patterns that can endure over time. These models reveal that complex behaviors can arise from local processes that are not directed by any overarching global rules, as theorized by Stephen Wolfram as early as 1986.

Following in the Organizational Change theories, it’s noteworthy how much continuous change is happening in the world, while at the same time, some organizations and knowledge structures experience very little change. On the other hand, organizations rise and fall, forming patterns that can be studied. The concept of “populations of organizations” refers to the dynamic collection of various organizations that exist, emerge, and dissolve over a specific time period within a certain geographic region. This population is characterized by constant flux, with numerous new organizations being established and many others dissolving. Most of these dissolutions involve small organizations, though occasionally large ones also disappear. While some organizations, like the Roman Catholic Church, have existed for millennia, the average lifespan of commercial organizations in Western countries, according to Stacey and Mowles, is about 40 years.

Organizations to be more durable need to leverage more than innovation strategies, and we might not want to engage in some of them.

Organizations to be more durable need to leverage more than innovation strategies, and we might not want to engage in some of them.This indicates that organizational populations are highly dynamic. Dynamics imply movement and focus on the evolving patterns of phenomena over time. Dynamic phenomena showcase change patterns, and the study of dynamics explores the factors generating these patterns and their properties of stability, instability, regularity, irregularity, predictability, and unpredictability.

Within any given period, organizations can merge, split, acquire others, or sell parts of themselves. They engage in supplying goods and services to each other and some hold regulatory power over others. Surviving organizations continuously evolve by altering their structures and activities, thereby affecting and creating opportunities for other organizations. The emergence of new technologies spawns entire new industries, offering niches for both new and existing organizations, while some industries vanish. Organizational strategies also involve downsizing, relocating activities across countries, and varying their operational scope from local to global.

The population includes a variety of organization types such as private, public, commercial, charitable, governmental, and industrial, all interacting in numerous ways. These interactions and transformations illustrate the highly dynamic nature of organizational populations. One key feature distinguishing different strategy and organizational change theories is their treatment of dynamics.

In addition to this element of dynamics, organizational populations undergo changes that simultaneously show stability and instability, predictability and unpredictability, creation and destruction. These contradictory tendencies complicate the understanding of organizational changes, and how one addresses these contradictions also influences the development of organizational change theories. Some theories aim to resolve contradictions, whereas others accept them as paradoxes that highlight human thought’s ability to simultaneously hold conflicting ideas.

The core focus of strategy and organizational change ultimately revolves around interactions. How interaction and interconnection are conceptualized differentiates various theories of strategy and organizational change. Most theories consider interactions as forming networks or systems – for example, an individual mind can be viewed as a system of interacting concepts, a group as a system of interacting individuals, and an organization as a system of interacting groups – but any industry can also be seen as a supra-system of interacting organizations, creating hierarchically nested systems. Different strategies and organizational change theories are based on different system theories.

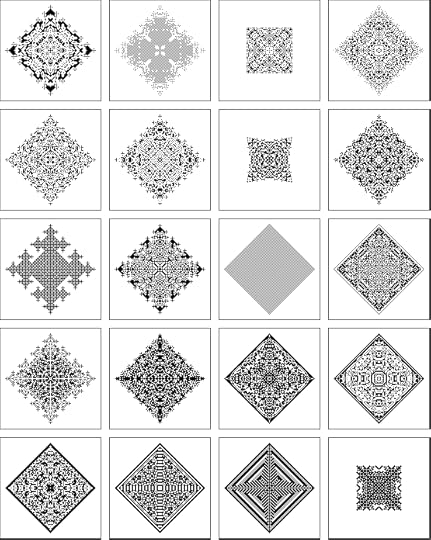

Patterns generated by two-dimensional cellular automata in Stephen Wolfram, A New Kind of Science. Wolfram Media, 2002.

Patterns generated by two-dimensional cellular automata in Stephen Wolfram, A New Kind of Science. Wolfram Media, 2002.The theory of Organizational Improvisation focuses on responsive processes and how understanding them provides an alternative to the idea of an opposition between “strong” (endogenous) and “weak” (exogenous) ways of thinking about processes in human action. But more about that tomorrow.

September 20, 2024

5+1 Games that Teach you Perspective

…and I don’t mean it metaphorically; I mean it literally. I recently discovered that many young artists either struggle with the rules and concepts of perspective or find that boring, as they’re more oriented towards character and creature design, so here’s a list of games that use either perspective or axonometric representation as a really clever narrative device and might give you the kick you’re missing.

5. EchochromeProbably the father of all that will follow, Echochrome is a puzzle video game developed by Japan Studio and published by Sony Computer Entertainment in 2008 for the PlayStation 3, and later for the PlayStation Portable. The game is among the firsts to make an innovative use of perspective and optical illusions, drawing inspiration from the artwork of M.C. Escher. Players control a character known as the “Echo,” navigating through a series of levels that are designed around impossible geometries. The core mechanic of the game involves manipulating the camera angle to change the perspective of the environment and create paths that would otherwise be inaccessible, effectively turning impossible structures into navigable spaces.

4. FezFez is a 2012 indie puzzle-platform game developed by Polytron Corporation and created by designer Phil Fish. Celebrated for its innovative gameplay mechanics, unique visual style, and rich exploration elements, it features Gomez, a 2D creature living in a platform-like 2D world, who receives a magical fez that allows him to perceive his environment in three dimensions. Akin to Abbott’s novel Flatland, the character gains consciousness of a dimension numerically superior to its own, and this enables players to rotate the game world, revealing new paths and connections between platforms that were previously inaccessible.

3. AntichamberA first-person puzzle game developed by Australian game designer Alexander Bruce, Antichamber was released in 2013 and it involves a unique, non-euclidean setting for puzzles created through what has been defined as an unconventional approach to game design. Players must explore these environments, solving puzzles by manipulating the world in unexpected ways, often involving hidden paths, laser beams, and using a special weapon to create and manipulate colored blocks. As players progress, they gain access to new abilities and tools, allowing them to access previously inaccessible areas. The game’s free-flowing, non-linear structure encourages experimentation and lateral thinking. Players have defined this experience with expressions like “my neurons hurt.”

2. Manifold GardenManifold Garden is a 2019 critically acclaimed first-person puzzle game developed by American artist William Chyr, and it’s known for its unique visual style and innovative gameplay that explores themes of infinity, recursion, and the nature of reality. Players navigate a surreal, geometric world again inspired by Escher, in a “universe with a different set of physical laws” where the player can manipulate gravity, being able to “turn walls into floors”. The goal is to solve puzzles by interacting with the world’s architecture and devices, using the game’s gravity-flipping mechanic to access new areas. Environments frequently appear to repeat into infinity in all directions, with abstract, fractal-like structures in shades of blue, white, and yellow.

The game was called “beautifully hypnotic” by Rock, Paper, Shotgun’s Philippa Warr and a “surreal masterpiece” by Polygon’s Nicole Carpenter.

1. Monument ValleyAt the top of my list, this 2014 mobile puzzle game by Ustwo Games and its two sequels see the silent protagonist, Princess Ida, wandering through a surreal, geometric world inspired by what M.C. Escher did with geometry and staircases. The game involves manipulating the world to uncover hidden paths and solve puzzles within optical illusions and impossible architecture to tell a story about Ida’s journey.

Monument Valley and its sequel have received numerous accolades, including the Apple Design Award and BAFTA awards for Best British Game and Best Mobile Game. The series has significantly influenced mobile gaming, encouraging developers to create shorter, more artistic experiences prioritising beauty and storytelling over obsessing with traditional gaming mechanics.

Bonus Feature: Pathfinder, Wrath of the RighteousIf you’re surprised, it means you didn’t play it.

This glorious isometric role-playing game developed by Owlcat Games and published by META Publishing features a chapter, around the middle of the game, in which you and your companions are stuck in a realm called Midnight Isles, and you travel between the lower city and the upper city trying to negotiate (or trick) your way out of there. The only problem is that the whole world rotates and morphs every time you turn the camera, creating actual passages where you thought there were only illusions.

They did a kick-ass job that can hardly be explained. And the game is delightful too. I suggest you go and play it.

September 19, 2024

8+1 Games that Teach you Math

Yesterday, we saw 12 video games that teach you how to code, but what if you’re dealing with people who need a motivational boost with a foundational concept like math? Well, look no more. Here’s a selection of 8+1 games that might do the trick.

1. DragonBoxDragonBox is an award-winning series of educational math games developed by WeWantToKnow AS, a Norwegian studio. The series aims to teach children various mathematical concepts, including algebra, number sense, and geometry, through engaging and interactive games designed to make learning math enjoyable and intuitive, helping children understand complex concepts without the frustration often associated with traditional teaching methods. Players engage in activities that involve organizing cards or manipulating colourful characters called Nooms, which represent numbers, and the games cater to various age ranges, with specific titles designed for younger children (ages 4-8) and more advanced players (ages 8 and up). Each game focuses on different aspects of math, such as basic arithmetic, algebra, and geometry. It received multiple awards for its innovative approach to education, including the Games for Change award for “Best Learning Game” in 2016.

In detail, the main programs are:

DragonBox Numbers, which focuses on developing foundational skills in number recognition, counting, and basic addition and subtraction. It uses characters called Nooms to help children understand how numbers work in a playful environment, and it’s suitable for ages 4-8.DragonBox Algebra 5+ and 12+, that introduces players to algebraic concepts such as solving equations, understanding variables, and manipulating expressions, and gradually progresses from simple to more complex algebraic ideas, including addition and subtraction of variables, multiplication and division, understanding and applying the order of operations, working with parentheses and factorization.DragonBox Elements, which teaches geometric concepts, including the properties and relationships of shapes. Players engage with Euclidean proofs and explore the characteristics of various geometric figures, enhancing their spatial reasoning skills;DragonBox BIG Numbers, focusing on long addition and subtraction like carrying over in addition. It helps children develop a deeper understanding of larger numbers and the operations involved in manipulating them.There are also DragonBox Algebra games that cover more advanced topics for older students, such as solving linear equations, understanding inequalities, working with functions, and graphing.

2. Slice FractionsSlice Fractions is an educational video game developed by Ululab, designed to help children aged 5 to 12 learn and understand fractions through engaging gameplay when they are just beginning to grasp the concept at traditional school. Players navigate a colourful prehistoric world where they must solve physics-based puzzles to free a woolly mammoth trapped in blocks of ice. The core mechanic involves slicing through ice and lava blocks, which introduces and reinforces fraction concepts. It includes over 140 innovative puzzles that gradually introduce more complex fraction concepts as players progress.

The game’s development involved collaboration with educational experts and researchers, ensuring that it aligns with educational standards and effectively teaches mathematical concepts. If you want to know more, you can read this paper.

3. Moose MathMoose Math is an educational video game developed by Duck Duck Moose, specifically designed for children aged 3 to 7. Released on October 15, 2013, it provides an interactive approach to learning foundational math concepts suitable for kindergarten and first-grade students.

The game features an adaptive learning system that tailors content based on each child’s progress, ensuring a personalized experience that meets individual learning needs. As children complete activities, they earn rewards that allow them to build and decorate their own city, adding an element of creativity and motivation to the learning process.

Activities include:

Moose Juice, in which Players make smoothies while practising counting, addition, and subtraction;Pet Bingo, a bingo game where children solve math problems to win;Paint Pet, where Kids match pets by counting dots;Lost & Found, which Involves sorting shapes and colours;Dot to Dot, where players help a character find its way home by connecting dots.Moose Math covers essential math topics aligned with Common Core State Standards, including:

Number Sense: understanding the relationship between numbers and quantities and solving word problemsMastering Counting by 1s, 2s, 5s, and 10s, and counting up to 100;Addition and Subtraction up to 20 using various methods, including dice and visual aids;Geometry: identifying and recognizing simple shapes appropriate for kindergarten and first-grade levels;Understanding and comparing lengths to aid their spatial thinking.4. Tami’s TowerNot strictly about math but worth a mention anyway, Tami’s Tower is an educational game developed by the Smithsonian Science Education Center, aimed at teaching engineering design principles to young learners, particularly those in kindergarten through second grade. Players help Tami, a golden lion tamarin, reach delicious fruit by building a stable tower. The challenge lies in designing the tower with different shapes and materials, in such a way that it can withstand various obstacles and prevent it from toppling over. Tami’s Tower introduces players to basic engineering concepts, such as stability, weight distribution, and the importance of shape in design, it encourages students to reflect on their design choices and assesses their confidence in their solutions. In addition to the main gameplay, there is a Sandbox mode where students can experiment with different designs without the constraints of the main game, allowing for creative exploration.

5. MathmateerMathmateer is another educational video game standing between math and engineering, as it teaches math concepts through the fun of building and launching rockets. Players start by selecting from over 90 colourful rocket parts, and once the rocket is built, they watch it launch into space, where math missions take place. During 56 unique math missions with increasing difficulty levels, players must solve math problems involving numbers, fractions, decimals, counting, time, shapes, patterns or arithmetic operations. Players earn bronze, silver or gold medals based on their performance and can try to beat their high scores.

6. Toon MathToon Math is an educational video game designed to help young children aged 5 to 12 improve their math skills. The game is structured as an endless runner, where players navigate through various levels while solving math problems. The objective is to rescue friends who have been kidnapped and taken to Halloween Town, adding a narrative element to the gameplay.

7. Math LandMath Land is an educational video game developed by Didactoons, and it combines a pirate adventure theme with various mathematical challenges. Players take on the role of Ray, a pirate tasked with retrieving sacred gems that have been stolen by the evil pirate Max, and the game involves navigating through various islands filled with obstacles and traps, where players must solve math problems to progress. Math topics covered include addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, sorting numbers from higher to lower and understanding negative numbers. It features over 25 levels, each presenting unique challenges and puzzles.

8. Prodigy Math

8. Prodigy MathProdigy Math is an educational video game designed to help students in grades 1 through 8 (6-14 years old) improve their math skills through interactive gameplay. Developed by Prodigy Education Inc., the game combines elements of role-playing games (RPGs) with curriculum-aligned math content. Players create their own wizard and embark on a journey through a fantasy world filled with quests, battles, and challenges. As they progress, they encounter various monsters and other players, engaging in math duels to advance. The game features an adaptive algorithm that tailors math questions to each student’s individual learning level.

9. MathigonMathigon is an educational platform designed to make learning math engaging and interactive for students of all ages. It offers a variety of tools and resources that cater to different mathematical concepts such as algebra, geometry, calculus, and statistics, making it suitable for both classroom use and independent learning. One of the standout features of Mathigon is Polypad, a virtual math tool that allows students to manipulate shapes, create graphs, and explore mathematical concepts visually. Polypad supports activities related to geometry, algebra, and number theory, making it a versatile resource for hands-on learning.

Have you ever used any of these tools? Do you know any that I missed? Tell us in the comments.

September 18, 2024

12 Games that Teach you How to Code

Yesterday we saw how I prefer game thinking to create new processes, if compared to the mere gamification of an existing process, and quoted some examples. Today let’s make a focus at a specific category, which is games that teach you how to code.

Here’s my personal list of favourites.

1. CodeMonkeyCodeMonkey is an online game-based learning platform that teaches kids aged 5-14 how to code using real programming languages like CoffeeScript, Python, and Scratch, and allows players to build their own games in HTML5. Courses are designed to align with today’s educational standards and develop computational thinking, collaboration, and problem-solving skills, and CodeMonkey’s Classroom Dashboard makes it easy for teachers to manage students, track progress, and access detailed lesson plans. CodeMonkey offers webinars, documentation, and video tutorials to support teachers in implementing the curriculum.

Courses include:

Grades K-2: CodeMonkey Jr. and Beaver Achiever introduce block coding concepts using Scratch;Grades 2-5: Dodo Does Math and Coding Adventure teach text-based coding in CoffeeScript;Grades 6-8: Banana Tales and Coding Chatbots cover Python programming fundamentals and advanced concepts;Game Builder is the environment where students can create, share, and modify their own games using CodeMonkey elements.

2. CodinGameCodinGame is designed for developers to enhance their coding skills through increasingly difficult puzzles and multiplayer programming contests, timed challenges, artificial intelligence competitions, and code golf challenges. It supports over 25 programming languages, including Python, Java, C++, JavaScript, Ruby, making it accessible for learners at various levels, from beginners to experienced programmers.

For organizations, CodinGame offers customizable coding assessments, allowing employers to evaluate candidates’ skills through tailored tests and challenges.

3. CSS Diner

CSS Diner is an interactive game designed to teach users about CSS selectors in a fun and engaging way, particularly beneficial for beginners looking to grasp the basics in a practical context.

Players navigate through various levels, each presenting a unique challenge that requires the use of CSS selectors to select specific elements from a virtual dinner table. The game consists of 32 levels, each progressively increasing in complexity. As players advance, they learn how to apply different CSS selectors, including class selectors, ID selectors, and attribute selectors. Each level provides a visual representation of a dinner setting, where players must write CSS code to select items like plates, fruits, and utensils based on given instructions. For example, a level might ask players to select all apples or to select items based on their position relative to other elements.

4. Flexbox FroggyCSS selectors are patterns used in Cascading Style Sheets (CSS) to select and style HTML elements on a webpage. They are fundamental to web design, allowing developers to apply specific styles to desired elements based on various criteria.

Again in the realm of CSS, Flexbox Froggy is an interactive web-based game designed to teach users about CSS Flexbox, a powerful layout module in CSS. The game is ideal for beginners and provides a fun way to learn how to position and align elements on a webpage using Flexbox properties.

Players help Froggy and his friends reach their respective lily pads by writing CSS code. Each level presents a unique challenge that requires the application of different Flexbox properties, gradually increasing in difficulty. The game provides a visual layout of the flex container and its items, making it easier for players to understand how different Flexbox properties affect the positioning and alignment of elements.

5. CodeCombatCSS Flexbox, short for “Flexible Box Layout,” is a layout model in CSS that provides a way to arrange and align elements within a container. It was introduced in CSS3 and is particularly useful for creating responsive web designs that adapt to different screen sizes.

Aimed at students from grades 3 to 12 and their teachers, CodeCombat teaches Python, JavaScript, and other languages through a fantasy adventure where players write code to control their characters. Players solve puzzles and challenges that require coding skills to progress in the game.

The platform offers a structured curriculum that aligns with computer science education standards. It provides a comprehensive learning path, making it suitable for both beginners and those looking to enhance their programming skills, and it’s designed to be accessible to teachers with no prior programming experience, enabling them to introduce coding to their students effectively while they learn it themselves.

6. UntrustedUntrusted is a meta-JavaScript adventure game where players guide the character Dr. Eval through a mysterious Machine Continuum. To progress, players must literally edit and re-execute the JavaScript code running the game in their browser to alter reality and find freedom.

The game presents a roguelike-like playing environment and a console window with the JavaScript code generating each level. As loaded, each level is unbeatable and most of the JavaScript is blocked from editing: the challenge is to open a path to the next level using only the limited tools left open for editing. It was created by Alex Nisnevich and Greg Shuflin, and uses the rot.js library for the game engine and CodeMirror for the code editor.

7. RobocodeRobocode is a programming game in which players create and control virtual robots in a competitive battle arena. Players act as programmers who write the AI for their robots, which will autonomously navigate a battlefield and engage in combat with other robots. The gameplay emphasizes strategy and coding skills, as players must develop algorithms that dictate their robots’ movements and actions. The primary goal is to code a robot that can outsmart and defeat other robots in Java or .NET, providing a fun and interactive way to learn programming.

The game can run on any operating system that supports Java, including Windows, macOS, and Linux.

Initially developed by Mat Nelson and later taken over by Flemming N. Larsen, Robocode is an open-source project that allows for continuous improvements and contributions from the community, ensuring the game remains up-to-date and relevant.

8. CheckIOCheckIO is an online strategy game platform that teaches to solve problems using Python or JavaScript through engaging coding games and collaborative challenges. Players write code to solve puzzles and progress through different levels, while encouraging collaboration and knowledge sharing. It provides several learning paths, each focusing on a specific aspect of programming:

Elementary: introduces basic programming concepts and syntax;Home: covers more advanced topics and problem-solving techniques;Incinerator: challenges players with complex coding problems;Polygon: allows users to create and share their own coding challenges.It offers a free version with limited access to missions and features. Premium plans are available for individuals and organizations, providing access to more missions, classroom tools, and priority support.

9. VIM AdventuresVIM Adventures is an online game designed to teach players how to use the VIM text editor through a Zelda-like adventure, focusing on keyboard shortcuts and commands. Players navigate through a 2D world, interacting with characters and solving puzzles to progress through the game, gradually increase in complexity, introducing new VIM concepts and challenges. As players advance, they encounter obstacles that can only be overcome by using specific VIM commands. Players can view their collected VIM keys and their corresponding functions by accessing an in-game keyboard. This feature serves as a quick reference for the commands learned so far.

It was developed by Doron Linder.

10. Elevator SagaVim, short for “Vi IMproved,” is a highly configurable and powerful text editor that is widely used in programming and text editing. Developed by Bram Moolenaar and released in 1991, Vim is an enhanced version of the original Unix text editor, vi. It is available across multiple platforms, including Unix, Linux, Windows, and macOS.

Elevator Saga is an interactive programming game that challenges players to write JavaScript code to control elevators in a simulated environment with the objective to efficiently transport passengers to their desired floors while optimizing for time and wait conditions. The game requires writing functions that dictate how elevators should behave based on various scenarios, and consists of multiple levels, each presenting unique challenges that increase in complexity. Players must adapt their code to meet specific criteria and write JavaScript code to define two main functions: init (to set up the elevators and floors) and update (to manage the elevators’ movements during the game). The game runs simulations based on the provided code, allowing players to see the results of their logic in real time. As players apply their code, they receive immediate feedback on performance metrics, such as the number of transported passengers, elapsed time, and average wait time.

11. Cyber DojoCyber Dojo is an online platform that provides a web-based environment for practising coding and test-driven development (TDD). It allows users to write code and tests directly in the browser, submit their solutions, and receive immediate feedback on whether the tests pass or fail. Cyber Dojo supports collaboration by allowing multiple users to work on the same coding problem simultaneously. It displays the status of all participants’ tests, promoting a shared understanding of the problem. Every 5 minutes, Cyber Dojo automatically prompts users to rotate to a different computer, encouraging collaboration and knowledge sharing among the entire group.

The platform currently supports a wide range of programming languages, including C#, C++, C, Java, JavaScript, Objective-C, Ruby, Perl, Python, and PHP.

Cyber Dojo can be used in the following contexts:

Coding Dojos, which are collaborative coding events where developers practice programming techniques together;Pair Programming, where two developers work together on the same coding problem;Coding Interviews, as it provides a standardized environment for candidates to write and test code.Learning and Practice, for Individual developers who wish to practice coding exercises, learn new programming languages and improve their test-driven development skills.12. Code WarsCodewars is an online platform designed for software developers to improve their coding skills through practice and competition. It features a wide array of coding challenges known as “kata,” which are designed to help users ranging from beginner (8 kyu) to expert (1 kyu): each kata includes a problem statement, input data, and expected output, challenging users to write a function that meets the requirements. After solving a kata, users can compare their solutions with those of others, including “Best Practice” solutions that highlight optimal coding techniques. This feature encourages learning from peers and exploring different coding approaches.

Codewars supports over 55 programming languages, allowing users to practice in the language of their choice or learn new ones. Popular languages include Python, JavaScript, Ruby, Java, and C#.

Do you know any other games that teach programming? Tell us in the comments!

September 17, 2024

Game Thinking: Motivational Aspects

Motivation is at the heart of both gamification and game thinking, yet the way each approach taps into user motivation is fundamentally different: while both aim to encourage user engagement, they do so by leveraging different types of motivation, as gamification primarily targets extrinsic motivation, while game thinking focuses on intrinsic motivation. Let’s see how.

2.1. Extrinsic vs Intrinsic MotivationGamification is largely centred around extrinsic motivation, which means engaging users through external rewards or incentives. These external motivators are typically tangible or measurable outcomes that drive behaviour like the infamous points, badges, leaderboards, rewards, and achievements. These elements should encourage users to participate in activities or complete tasks to gain recognition, earn rewards, or compete with others. The external nature of these motivators means that users are driven by what they will receive as a result of their actions, rather than the actions themselves.

Take for example an educational platform that uses gamification to encourage students to complete assignments. By awarding points for each task completed and offering badges for reaching certain milestones, the platform provides clear external incentives, but students are motivated to engage with the platform not necessarily because they enjoy the learning process: they want to earn rewards, see their name on the leaderboard, or unlock achievements… and they will find a way to cheat.

Research shows that while extrinsic rewards can effectively drive behaviour initially and kick-start change, they may not sustain long-term engagement. Once the external rewards are removed or they lose their appeal, users may lose interest in the task. Additionally, in some cases, reliance on extrinsic motivation can diminish intrinsic motivation, as users may begin to associate the task solely with the reward rather than finding inherent value or enjoyment in the activity itself.

Game thinking, in contrast, seeks to trigger intrinsic motivation, which arises when individuals are motivated to engage in an activity because they find it inherently satisfying, enjoyable, or meaningful. In other words, the activity itself becomes the reward. Game thinking aims to create experiences that naturally appeal to users’ internal desires, such as the need for mastery, autonomy, purpose, and a sense of accomplishment.

Intrinsic motivation is more powerful and sustainable over the long term because it taps into fundamental human needs and desires. When a system or experience is designed with game thinking, users are motivated to participate because they find the process itself engaging, challenging, or meaningful. They don’t need external rewards to keep them going; the experience itself provides a sense of fulfillment.

2.2. The Interplay Between Extrinsic and Intrinsic MotivationFor example, in the context of professional development, a platform designed with game thinking might not just award points for completing training modules. Instead, it could incorporate elements of storytelling and create a journey where employees are encouraged to take on progressively challenging tasks, develop new skills, and see their growth over time.

While gamification and game thinking can be seen as distinct in their focus on extrinsic and intrinsic motivation, the relationship between these two types of motivation is more complex. In many cases, extrinsic and intrinsic motivation can work together to enhance user engagement.

As we’ve seen, bagdes and such can be effective in quick-starting a new wave of different behaviours, and this is good through the first stages of change management when, for instance, you need to encourage people to participate in the assessment stages. Over-reliance on extrinsic motivation, however, can sometimes undermine intrinsic motivation. This is known as the “overjustification effect,” where the introduction of external rewards can reduce a person’s intrinsic interest in a task. Game thinking steps in to avoid this pitfall by designing systems that align with users’ internal drives from the outset, experiences that are enjoyable, meaningful, and challenging.

2.3. Long-Term vs. Short-Term EngagementThe distinction between extrinsic and intrinsic motivation, thus, has implications for the sustainability of user engagement. Gamification, with its reliance on extrinsic motivators, can be highly effective in driving short-term engagement, as users are drawn to the immediate gratification of earning points, rewards, or recognition. However, as mentioned earlier, this type of motivation can be fleeting, and without careful design, it may not lead to long-term behaviour change which is what we seek to achieve.

Game thinking, by fostering intrinsic motivation, is often better suited for creating long-term engagement. When users are motivated by the experience itself, they are more likely to continue participating over time. This approach encourages a deeper connection with the task or system, leading to sustained engagement that is less dependent on external factors.

3. Success Cases and ExamplesClasscraft is a platform that transforms the classroom into a role-playing game. Students create characters and earn experience points by completing assignments and collaborating with peers. This approach not only motivates students but also encourages teamwork and social interaction, demonstrating the effectiveness of game thinking in fostering a positive learning environment.

The World Bank also utilized a game-based approach to engage stakeholders in urban planning. By simulating city management scenarios, participants could explore the consequences of various policies in a controlled environment. This method not only facilitated understanding but also encouraged innovative thinking about complex urban issues.

In the health sector, game thinking has been applied to encourage healthier lifestyles. For instance, platforms like Zombies, Run! gamify exercise by integrating storytelling and missions into running. Users must complete tasks while running, which increases motivation and engagement with physical activity, and the approach has shown promising results in improving fitness levels among participants. The best however happens when healthier behaviours spring as a byproduct of an actual game, without it being a serious game or specifically designed as educational. But that’s a story for a different time.

September 16, 2024

Game Thinking: Approach and Depths

The concepts of gamification and game thinking represent two distinct approaches when it comes to the depth of engagement you’re seeking for your users. At their core, both aim at creating more compelling and enjoyable experiences in non-game contexts, but they differ in nature, specifically in terms of how they are implemented and the philosophical underpinnings of each.

1.1. Surface-Level Engagement vs. Holistic DesignI know I won’t make many friends by saying this, but gamification is often characterized by a surface-level approach, as it tends to focus on adding game-like mechanics to existing systems. These mechanics are layered onto a pre-existing framework to make it more engaging and create bursts of motivation by tapping into competitive instincts, reward-seeking behaviour, or the desire for recognition, which are all good and fine except I’m kidding, they’re not, and they often thrive into toxic environments where explorers aren’t encouraged and managers wish to foster people’s killer/achiever instincts. Morever, gamified elements do not fundamentally alter the system’s underlying structure or logic, as we’ve seen. Instead, they enhance engagement by incorporating external incentives, providing users with reasons to complete tasks that might otherwise feel mundane or repetitive.

Game thinking, by contrast, delves into a deeper, more holistic approach to design. It is not simply about adding game mechanics to a system but about reimagining the entire experience through different lenses. It draws on a comprehensive understanding of what makes games inherently compelling and uses that understanding to build systems from the ground up that naturally motivate and engage users. The experience is designed to be meaningful, where engagement arises not just from external rewards but from the experience itself.

Consider the difference between adding a points system to an employee task management tool (gamification) versus designing a workflow process that feels like a quest, with built-in challenges, opportunities for mastery, and a sense of progression (game thinking). The latter requires a deeper level of design, as it transforms the nature of the work itself, rather than simply incentivizing the completion of tasks.

Are you going to the office, my little hobbit? Nope.1.2. Extrinsic vs. Intrinsic Motivation

Are you going to the office, my little hobbit? Nope.1.2. Extrinsic vs. Intrinsic MotivationA key aspect of the difference in approach and depth between gamification and game thinking lies in their relationship with motivation. Gamification often relies on extrinsic motivation, which involves encouraging users to engage in an activity because of an external reward, such as earning points or winning a prize. This approach can be practical in short bursts or in contexts where the task itself isn’t likely to provide satisfaction naturally.

Game thinking, however, seeks to tap into intrinsic motivation, where users engage with a system because they find the activity itself rewarding and fulfilling. This deeper level of engagement is achieved by creating an experience that resonates with the user’s internal drives, such as the desire for mastery, autonomy, purpose, or a sense of accomplishment. In game thinking, the task is designed to be inherently engaging, so users are motivated by the challenge, the journey, or the satisfaction of solving problems. The focus shifts from merely completing a task for a reward to enjoying the process of achieving something meaningful. So you might see why I like it more.

1.3. Incremental Changes vs. Systemic OverhaulAnother distinction between the two approaches is the level of change they introduce to the system. Gamification typically involves incremental changes: it enhances an existing process by adding game elements to make it more engaging, it can be a relatively low-cost and it’s seen as a quick way to boost user engagement, as it does not require a complete overhaul of the system.

Game thinking, on the other hand, often requires a systemic overhaul. It involves rethinking the entire user experience from the ground up, applying the principles of game design to create a system that is inherently engaging and motivating. This approach demands a deeper understanding of user psychology, behavior, and the emotional impact of the experience, but also requires a complete understanding of the values we bring to the users, which might be tricky when our users are our employees and managers just expect to squeeze value out of them without giving anything back in return. Game thinking does not just add a layer of engagement; it transforms the very nature of the system to make it more like a game in its structure, progression, and user experience.

Tomorrow we’ll see what’s the focus on motivation.

September 15, 2024

Game Thinking vs Gamification (and where do I stand)

Why are you interested in games?

I’ve been asked this question a lot, lately, partially because of my upcoming class on LEGO Serious Play at Autodesk University and partially for my growing involvement with the Event Horizon School of Digital Arts. A friend recently asked if they could introduce me at a conference as a “gamification expert”. And I had to answer “no”. Not because I don’t consider myself an expert (which is true, but it’s also my imposter syndrome speaking), but because the g-word carries a lot of baggage, and personally I prefer to say I work through game thinking. What’s the difference, you ask? Well, I’m glad you did.

Gamification vs. Game ThinkingGamification and game thinking are two approaches that draw inspiration from games, yet they have different goals, methods, and applications. While both concepts utilize elements of game design to engage and motivate people, they operate in distinct ways, often leading to different outcomes.

Gamification refers to the application of game elements in non-game contexts to increase user engagement, motivation, and participation. These elements can include badges, leaderboards, rewards, levels, challenges, and progress tracking. Gamification is often used in marketing, education, productivity apps, and employee engagement initiatives, and it’s tricky because it will fall flat or backfire if it isn’t introduced within the correct company culture. The goal is to make mundane tasks more enjoyable by introducing incentives and competition, but people won’t enjoy themselves if the company is toxic, no matter how many badges you create for them.

For example, fitness apps often use gamification by allowing users to earn points for completing workouts, compete against friends on leaderboards, and unlock badges for reaching milestones. By incorporating these elements, the app encourages users to exercise more regularly, turning a routine task into a rewarding and engaging experience.

Game thinking, on the other hand, is a broader and deeper concept that involves designing systems, products, or experiences with the principles and psychology of game design at their core. Rather than merely adding game-like elements to an existing system, game thinking focuses on creating an experience that intrinsically motivates users through a journey, challenges, and mastery. While gamification tweaks and fine-tunes (and often just embellishes), game thinking is about understanding what makes games so compelling and then applying that understanding to solve problems or create innovative solutions in non-game contexts. It encompasses things like behavioral psychology and user-centered design (more on that later), and places its emphasis is on creating meaningful and engaging experiences that resonate with users on an emotional level.

For example, in the context of a learning platform, game thinking would not simply add badges or points to motivate students but would involve designing an experience where students feel a sense of autonomy, mastery, and purpose, much like players do in a well-designed game. The platform might include adaptive challenges, narrative-driven content, and a sense of progression that keeps students intrinsically motivated to continue learning.

In these following days we’ll see some key difference between gamification and game thinking, and I’ll try to articulate why I like the latter better.

September 14, 2024

Enquiry by Design (EbD) Step-by-Step: Transitioning to Implementation

It might be tough to hear, but the hardest part of activities such as Equiry by Design is ensuring that the work done by the groups is… actually used.

The success of the activity in fact is measured not only by the creativity and collaboration it fosters during the event but also by the real-world impact it generates afterward. Transitioning from the activity to implementation is a critical phase, where the design proposals developed by participants move from ideas to actionable plans. Ensuring that the work done by the groups is actually used requires careful planning, strong communication, and sustained engagement with stakeholders. This transition is about building momentum and ensuring that the energy and innovation from the event continue to drive the project forward.

Let’s see how.

1. Documenting and Synthesizing the OutcomesThe first step in transitioning from the activity to implementation is to thoroughly document and synthesize the outcomes of the event. This includes capturing all design proposals, key insights, stakeholder feedback, and any decisions made during the final presentations and discussions. Proper documentation is essential to ensure that nothing is lost in translation as the project moves forward.

A comprehensive report should be created that outlines each group’s design concepts, the rationale behind their proposals, and the feedback received, ideally through rich visual elements (such as maps, sketches, and renderings), written explanations that clearly articulate the key ideas and comparative tables. The documentation should also highlight the main themes that emerged during the event, showing how different proposals align with broader strategic goals or address specific challenges.

Eg: the report might include a section summarizing how the various proposals collectively address the need for improved connectivity in a redevelopment area, or how they integrate sustainability principles.

Once the report is compiled, it should be distributed to all participants, stakeholders, and decision-makers. Sharing this documentation helps to maintain transparency and ensures that everyone involved in the project has access to the full scope of work produced during the activity. It also serves as a reference point for future discussions, ensuring that the ideas generated during the event are consistently referenced and built upon in the implementation phase.

2. Engaging Decision-Makers and Securing CommitmentTo ensure that the work done by the groups is actually used, it’s crucial to engage decision-makers early and secure their commitment to moving forward with the proposals. This means involving key stakeholders—such as local government officials, developers, community leaders, and funding agencies—in the transition process and ensuring that they understand the value of the designs produced during the EbD activity.

One way to engage decision-makers is to organize follow-up meetings or workshops where the outcomes of the activity are presented and discussed in more detail. These sessions should focus on how the design proposals align with existing policies, plans, and strategic objectives, and how they can be integrated into ongoing or future projects. By framing the proposals within the context of broader development goals, the organizing team can make a compelling case for why the ideas generated during the event should be implemented.

Eg: if the activity focused on revitalizing a downtown area, the follow-up meeting might involve local government planners and economic development officials who can discuss how the design proposals align with the city’s long-term goals for economic growth and community revitalization. The discussion could explore how the proposals can be integrated into the city’s master plan or capital improvement program, ensuring that the ideas are supported by policy and funding.

It’s also important to identify champions within the decision-making bodies—individuals who are particularly enthusiastic about the outcomes of the EbD activity and who can advocate for the implementation of the proposals. These champions can help to push the ideas forward, ensuring that they remain a priority as the project moves into the next phases of planning and development.

3. Creating an Action PlanTo move from ideas to implementation, it’s essential to create a clear action plan that outlines the steps needed to turn the design proposals into reality. This action plan should break down the implementation process into manageable phases, with specific tasks, timelines, and responsible parties assigned to each phase.

The action plan should start by identifying any additional work that needs to be done to further develop the design proposals. This might include detailed engineering studies, environmental impact assessments, or cost-benefit analyses. The plan should also identify any regulatory approvals or permits that need to be secured, as well as any funding sources that need to be pursued.

It’s important to ensure that the action plan is realistic and achievable. This means setting clear priorities and focusing on the most critical elements of the design proposals that can be implemented in the short term, while also outlining longer-term goals that will require more time and resources to achieve. By breaking down the process into clear, actionable steps, the organizing team can maintain momentum and ensure that progress continues after the activity concludes.

The action plan should also include regular check-ins and progress updates, ensuring that all stakeholders remain engaged and that any challenges or obstacles are addressed promptly. This continuous monitoring helps to keep the implementation process on track and ensures that the ideas generated during the EbD activity are not sidelined or forgotten.

4. Leveraging Partnerships and ResourcesEg: if one of the proposals involves creating a new public park, the action plan might outline the steps needed to secure land ownership or zoning changes, develop detailed landscape designs, and apply for grants or public funding to cover the costs of construction. The plan would assign these tasks to specific team members or external partners and establish a timeline for completing each step.

Successful implementation often requires collaboration with a range of partners, including government agencies, private developers, non-profit organizations, and community groups. Leveraging these partnerships is key to turning the design proposals into reality, as different stakeholders bring different resources, expertise, and influence to the table.

The organizing team should identify potential partners who can help support the implementation of the proposals. This might include engaging with local businesses that could sponsor or invest in certain elements of the project, partnering with non-profits that specialize in community development, or working with government agencies to secure funding or regulatory support.

Eg: if one of the design proposals involves creating affordable housing, the organizing team might engage with housing authorities, non-profit developers, and financial institutions to explore funding opportunities, land acquisition strategies, and regulatory incentives. These partnerships can help to ensure that the project moves forward and that the ideas generated during the activity are not just theoretical but are backed by the resources needed to implement them.

It’s also important to explore different funding sources that can support implementation. This might involve applying for grants, securing public funding, or attracting private investment. The organizing team should work closely with financial experts and stakeholders to identify the most appropriate funding mechanisms for each element of the project.

5. Maintaining Stakeholder Engagement and CommunicationSustained stakeholder engagement is critical to ensuring that the work done during the activity is actually used in the implementation phase. This means maintaining regular communication with all participants, keeping them informed about progress, and providing opportunities for ongoing involvement. These updates help to maintain transparency and ensure that participants feel connected to the project as it moves forward.

Eg: the organizing team might send out regular email updates or newsletters that keep participants informed about key milestones, upcoming meetings, and any challenges that have arisen.

In addition to communication, it’s important to continue involving stakeholders in the decision-making process. This could involve organizing follow-up workshops or working groups where stakeholders can provide input on specific aspects of the implementation, such as refining the design details, addressing community concerns, or exploring new opportunities that arise as the project progresses.

By keeping stakeholders engaged and involved, the organizing team ensures that the implementation process remains collaborative and that the ideas generated during the activity continue to reflect the needs and aspirations of the community.

6. Tracking Progress and Measuring SuccessFinally, it’s important to track progress and measure success throughout the implementation phase. This involves setting clear benchmarks for what successful implementation looks like and regularly assessing whether the project is meeting those benchmarks.

The organizing team should establish key performance indicators that can be used to measure progress, with all the needed caution for Key Performance Indicators (more on that in the following days). These might include metrics related to project milestones, such as the completion of design documents or the securing of funding, as well as longer-term outcomes, such as improved public spaces, increased community engagement, or economic growth. By regularly reviewing these metrics and making adjustments as needed, the organizing team can ensure that the implementation process remains aligned with the goals of the EbD activity and that the work done by the groups is actually used to create real-world impact.

Eg: if one of the design proposals involves creating a new public park, the KPIs might include securing land ownership, completing construction, and tracking park usage and community satisfaction after the park opens. These metrics help to ensure that the project stays on track and that the outcomes of the EbD activity are actually realized in the community.

That’s all for now! If you’ve witnessed, organized or participated into a similar activity, please don’t forget to share your experience in the comments.

The picture in the header comes from the article “Participatory Urban Planning and Design”