Kathleen Jones's Blog, page 23

March 14, 2016

Poetry, Politics and Ben Okri

It's been a lively weekend. On Friday I caught a train to London to take part in the Magma poetry magazine prize celebration at Keats House in Hampstead. The weather was beautiful - clear blue skies - and the trees were coming into bud and the birds were singing. London at its best. The poetry was good too; Daljit Nagra was this year's judge and the winners for 2 categories of prize - from USA and UK - included Lucy Ingrams, Maya Popa, Soul Patel, Maggie Smith, Paul Bregazzi and Barbara Hickson. The special mentions also got to read their work, and they included some stunning poems. Daljit Nagra was honest enough to say that out of the huge number of poems submitted, the 8 poems eventually selected for each prize could have been in any order - the ordering was entirely subjective. But I don't think I could have disagreed with his decisions. Among the special mentions for both categories were Robert Hamberger, Mario Petrucci, Lesley Saunders, Rebecca Watts, Neil Ferguson, Simon Richey, Catherine Edmunds, Polly Atkin, and Louise Vale, as well as myself. 3 of the UK poets came from Cumbria - Barbara, Polly and me, so there must be something special in the air! These are some of the prize-winners (not intentionally ordered by height).

Neil Fergusson, Robert Hamberger, Daljit Nagra, Barbara Hickson, Paul Bregazzi, Lesley Saunders, Kathleen JonesSaturday I was back on the train for a series of events at the Words by the Water Festival in Keswick. On Sunday morning novelist Salley Vickers was giving the Royal Literary Fund lecture on Shakespeare. I didn't think that there was anything left to say about the Bard, but Salley had the audience riveted and I learned a lot. She was very impressive. Business and Economics editor at Channel 4, Paul Mason, recently resigned because of the politics of broadcast media, was terrifying as he talked about a Future after Capitalism. He gave a damning view of the press as it is at present, in the hands of oligarchs and a political elite, all pursuing their own agendas rather than serving the public with information. Another crisis is inevitable, he said, and conditions will get much worse than we could ever imagine. Our future is in co-operation and a much more local outlook. And don't trust the banks (or the government!) with your money.

Neil Fergusson, Robert Hamberger, Daljit Nagra, Barbara Hickson, Paul Bregazzi, Lesley Saunders, Kathleen JonesSaturday I was back on the train for a series of events at the Words by the Water Festival in Keswick. On Sunday morning novelist Salley Vickers was giving the Royal Literary Fund lecture on Shakespeare. I didn't think that there was anything left to say about the Bard, but Salley had the audience riveted and I learned a lot. She was very impressive. Business and Economics editor at Channel 4, Paul Mason, recently resigned because of the politics of broadcast media, was terrifying as he talked about a Future after Capitalism. He gave a damning view of the press as it is at present, in the hands of oligarchs and a political elite, all pursuing their own agendas rather than serving the public with information. Another crisis is inevitable, he said, and conditions will get much worse than we could ever imagine. Our future is in co-operation and a much more local outlook. And don't trust the banks (or the government!) with your money.

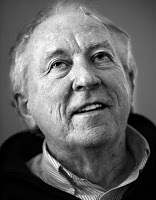

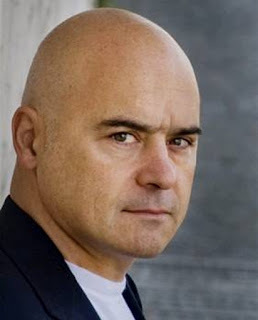

Paul Mason (whatever it says on the board) and a long queue to sign books. Photo Gwenda Matthews at BookendsBut the final event of the day, at the end of the Festival, was Ben Okri talking about storytelling. It is, he said, fundamental to the human psyche, pre-dating, perhaps, even our use of tools and technologies. As soon as human beings had language, they had story. He talked about the 'transgressive' quality of stories and the mysteries at the heart of them. "Stories are never what they seem. They are whispers from beyond the invisible screen of existence." He talked about the importance of the imagination and allowing children creative play. "Imagination dreams that which knowledge makes real . . . A people can only create what they can imagine."

Paul Mason (whatever it says on the board) and a long queue to sign books. Photo Gwenda Matthews at BookendsBut the final event of the day, at the end of the Festival, was Ben Okri talking about storytelling. It is, he said, fundamental to the human psyche, pre-dating, perhaps, even our use of tools and technologies. As soon as human beings had language, they had story. He talked about the 'transgressive' quality of stories and the mysteries at the heart of them. "Stories are never what they seem. They are whispers from beyond the invisible screen of existence." He talked about the importance of the imagination and allowing children creative play. "Imagination dreams that which knowledge makes real . . . A people can only create what they can imagine."

The magical Ben Okri - photo Gwenda Matthews at Bookends

The magical Ben Okri - photo Gwenda Matthews at Bookends

Neil Fergusson, Robert Hamberger, Daljit Nagra, Barbara Hickson, Paul Bregazzi, Lesley Saunders, Kathleen JonesSaturday I was back on the train for a series of events at the Words by the Water Festival in Keswick. On Sunday morning novelist Salley Vickers was giving the Royal Literary Fund lecture on Shakespeare. I didn't think that there was anything left to say about the Bard, but Salley had the audience riveted and I learned a lot. She was very impressive. Business and Economics editor at Channel 4, Paul Mason, recently resigned because of the politics of broadcast media, was terrifying as he talked about a Future after Capitalism. He gave a damning view of the press as it is at present, in the hands of oligarchs and a political elite, all pursuing their own agendas rather than serving the public with information. Another crisis is inevitable, he said, and conditions will get much worse than we could ever imagine. Our future is in co-operation and a much more local outlook. And don't trust the banks (or the government!) with your money.

Neil Fergusson, Robert Hamberger, Daljit Nagra, Barbara Hickson, Paul Bregazzi, Lesley Saunders, Kathleen JonesSaturday I was back on the train for a series of events at the Words by the Water Festival in Keswick. On Sunday morning novelist Salley Vickers was giving the Royal Literary Fund lecture on Shakespeare. I didn't think that there was anything left to say about the Bard, but Salley had the audience riveted and I learned a lot. She was very impressive. Business and Economics editor at Channel 4, Paul Mason, recently resigned because of the politics of broadcast media, was terrifying as he talked about a Future after Capitalism. He gave a damning view of the press as it is at present, in the hands of oligarchs and a political elite, all pursuing their own agendas rather than serving the public with information. Another crisis is inevitable, he said, and conditions will get much worse than we could ever imagine. Our future is in co-operation and a much more local outlook. And don't trust the banks (or the government!) with your money. Paul Mason (whatever it says on the board) and a long queue to sign books. Photo Gwenda Matthews at BookendsBut the final event of the day, at the end of the Festival, was Ben Okri talking about storytelling. It is, he said, fundamental to the human psyche, pre-dating, perhaps, even our use of tools and technologies. As soon as human beings had language, they had story. He talked about the 'transgressive' quality of stories and the mysteries at the heart of them. "Stories are never what they seem. They are whispers from beyond the invisible screen of existence." He talked about the importance of the imagination and allowing children creative play. "Imagination dreams that which knowledge makes real . . . A people can only create what they can imagine."

Paul Mason (whatever it says on the board) and a long queue to sign books. Photo Gwenda Matthews at BookendsBut the final event of the day, at the end of the Festival, was Ben Okri talking about storytelling. It is, he said, fundamental to the human psyche, pre-dating, perhaps, even our use of tools and technologies. As soon as human beings had language, they had story. He talked about the 'transgressive' quality of stories and the mysteries at the heart of them. "Stories are never what they seem. They are whispers from beyond the invisible screen of existence." He talked about the importance of the imagination and allowing children creative play. "Imagination dreams that which knowledge makes real . . . A people can only create what they can imagine." The magical Ben Okri - photo Gwenda Matthews at Bookends

The magical Ben Okri - photo Gwenda Matthews at Bookends

Published on March 14, 2016 13:23

March 9, 2016

Kirsty Gunn: My Katherine Mansfield Project

Yesterday was International Women's Day and I spent it at the

Words by the Water Festival

of 'words and ideas' in the beautiful Theatre by the Lake looking out over Derwentwater in Keswick.

Skiddaw from Derwentwater. Photo copyright David Welham, 'I Love the Lake District' FBI had the real pleasure of chairing an event by the New Zealand writer

Kirsty Gunn,

who was talking about her latest book from Notting Hill Editions, called 'My Katherine Mansfield Project'.

Skiddaw from Derwentwater. Photo copyright David Welham, 'I Love the Lake District' FBI had the real pleasure of chairing an event by the New Zealand writer

Kirsty Gunn,

who was talking about her latest book from Notting Hill Editions, called 'My Katherine Mansfield Project'.

It is a patchwork of fiction, memoir and reflection, written over the several months she recently spent in Wellington, New Zealand - the city where both she and Katherine were born and brought up - the city they both left as young women to come to England to become writers.

The resulting book is completely unclassifiable, in terms of genre, and is beautiful to read. The reflective sections are perhaps closest to the essay format - journeys of exploration through Kirsty's thoughts and feelings as she confronts both her past and Katherine Mansfield's, as well as her responses, in fiction, to some of Mansfield's most seminal stories.

It's one of my favourite books by Kirsty Gunn, partly because of the Mansfield link, but also because it is a wonderful piece of writing.

I also like her novella The Boy and the Sea and I'm an admirer of her most recent - Scottish - novel, The Big Music .

Kirsty is currently living between London and Scotland, where she is Professor of Creative Writing at Dundee University, so her reflections on the idea of Home and Belonging were very interesting. She knows very well the feeling of returning 'home' only to find that you are a stranger in your own country.

Notting Hill Editions are a wonderful 'boutique' publisher - I met the managing editor after the event and was very impressed with the passion and the dedication. They produce beautiful books. Take a look.

The Words by the Water Festival is on until Sunday with a wide variety of writers talking about their work. There's something for everyone. I'll be back on Sunday introducing novelist Sally Vickers, who is giving the Royal Literary Fund lecture this year.

Skiddaw from Derwentwater. Photo copyright David Welham, 'I Love the Lake District' FBI had the real pleasure of chairing an event by the New Zealand writer

Kirsty Gunn,

who was talking about her latest book from Notting Hill Editions, called 'My Katherine Mansfield Project'.

Skiddaw from Derwentwater. Photo copyright David Welham, 'I Love the Lake District' FBI had the real pleasure of chairing an event by the New Zealand writer

Kirsty Gunn,

who was talking about her latest book from Notting Hill Editions, called 'My Katherine Mansfield Project'.

It is a patchwork of fiction, memoir and reflection, written over the several months she recently spent in Wellington, New Zealand - the city where both she and Katherine were born and brought up - the city they both left as young women to come to England to become writers.

The resulting book is completely unclassifiable, in terms of genre, and is beautiful to read. The reflective sections are perhaps closest to the essay format - journeys of exploration through Kirsty's thoughts and feelings as she confronts both her past and Katherine Mansfield's, as well as her responses, in fiction, to some of Mansfield's most seminal stories.

It's one of my favourite books by Kirsty Gunn, partly because of the Mansfield link, but also because it is a wonderful piece of writing.

I also like her novella The Boy and the Sea and I'm an admirer of her most recent - Scottish - novel, The Big Music .

Kirsty is currently living between London and Scotland, where she is Professor of Creative Writing at Dundee University, so her reflections on the idea of Home and Belonging were very interesting. She knows very well the feeling of returning 'home' only to find that you are a stranger in your own country.

Notting Hill Editions are a wonderful 'boutique' publisher - I met the managing editor after the event and was very impressed with the passion and the dedication. They produce beautiful books. Take a look.

The Words by the Water Festival is on until Sunday with a wide variety of writers talking about their work. There's something for everyone. I'll be back on Sunday introducing novelist Sally Vickers, who is giving the Royal Literary Fund lecture this year.

Published on March 09, 2016 05:49

March 4, 2016

Travelling to the Edge of the World

It's nearly a year since I set off for the remote islands of Haida Gwaii off the northernmost coast of British Columbia. I thought I was going to write a few poems, hug some ancient trees, enjoy some profound peace and quiet, learn more about Haida mythology, and get in touch with the soul I'd lost in corporate Britain. What happened was quite different. The people I met, and the stories they told me, led me to write another book - part travel journal, part history.

Some books just demand to be written, and Travelling to the Edge of the World was one of them. It was written out of passion and commitment. Like most First Nation people of north America the Haida were the victims of cultural genocide, perpetrated by a colonial government, on an almost unbelievable scale. It was referred to as the 'Great Dying' and it reduced a population of more than twenty thousand down to only five hundred. Bill Reid - one of the most famous Haida artists - wrote that 'It is one of the world's greatest tributes to the strength of the human spirit that most of those who lived, and their children after them, remained sane and adapted.'

One of the rotting totems at SkedansI was taken to see the abandoned villages of the south islands, with their fallen houses and rotting totems and I met the young people who spend weeks voluntarily living in primitive conditions to protect their heritage from looting and vandalism. The Haida have survived and today they are one of the most prominent First Nation people leading the environmental movement in Canada to prevent their homelands from being exploited and polluted by oil companies and large corporations who don't have to live in the environments they destroy.

One of the rotting totems at SkedansI was taken to see the abandoned villages of the south islands, with their fallen houses and rotting totems and I met the young people who spend weeks voluntarily living in primitive conditions to protect their heritage from looting and vandalism. The Haida have survived and today they are one of the most prominent First Nation people leading the environmental movement in Canada to prevent their homelands from being exploited and polluted by oil companies and large corporations who don't have to live in the environments they destroy.

The Haida have produced what they call their 'Land Use Vision' - a document which embodies the principle of Yah'guudang, which is about 'respect and responsibility, about knowing our place in the web of life, and how the fate of our culture runs parallel with the fate of the ocean, sky and forest'. The 'Land Use Vision' is a blueprint for our survival. The Haida still know how to live in harmony with the world around them without destroying it. They have important things to teach us.

A wild and beautiful place - Inner Passage from Cormorant IslandAnd I met some wonderful people - a nonagenarian still running his own business, helped by a twelve year old boy; a poet married to a bank robber; an ex coastguard turned environmental activist; as well as artists and artisans, loggers and fishermen. British Columbia is a wild and wonderful place. But beware - there are bears in the woods!

A wild and beautiful place - Inner Passage from Cormorant IslandAnd I met some wonderful people - a nonagenarian still running his own business, helped by a twelve year old boy; a poet married to a bank robber; an ex coastguard turned environmental activist; as well as artists and artisans, loggers and fishermen. British Columbia is a wild and wonderful place. But beware - there are bears in the woods! A black bear I encountered on the beach

A black bear I encountered on the beachTravelling to the Edge of the World is available as an ebook, for an introductory offer. The paperback and i-book will be released at the end of March. You can buy it here.

Published on March 04, 2016 15:30

March 3, 2016

Words on World Book Day

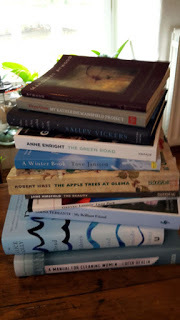

It’s World Book Day and this is what is in the TBR pile beside my bed. I have another one on Kindle!

There’s non-fiction - Alice Jolly’s Dead Babies and Seaside Towns; poetry - Jane Hirshfield’s The Beauty, Grevel Lindop’s Luna Park, as well as collections by Margaret Atwood and Robert Hass; fiction includes Elena Ferrante (I’m half way through), Anne Enright, Tove Jansson and the wonderfully named ‘Manual for Cleaning Ladies’ by Lucia Berlin. My favourites so far are the Margaret Atwood poems; 'Morning in the Burned House', Tove Jansson's 'Winter Book', and a series of memoirs and reflections by NZ writer Kirsty Gunn; 'My Katherine Mansfield Project', which is really about exile and belonging. But as I read through the pile my preferences may change!

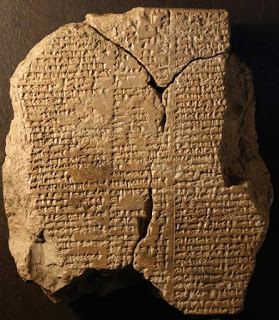

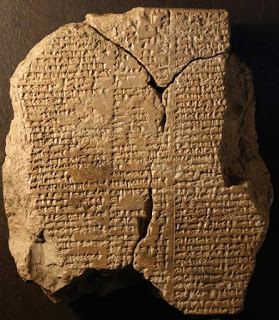

New text from the Epic of Gilgamesh discovered in Iraq - one of our earliest written stories.Books are my life - I’m surrounded by them, and I earn my living from them. I can’t think of a world without poems or stories. Recently I was intrigued to

find scholars admitting that the fairy tales

they sometimes scoff at were many thousands of years old. It's taken them all that time to admit what was evident

even to the Brothers Grimm?

Archaeologists have long found evidence of major historical and geological events in our mythologies. Noah and the Flood is just one of them; the legend of Atlantis another. Telling stories is as old as human history, as old as language.

New text from the Epic of Gilgamesh discovered in Iraq - one of our earliest written stories.Books are my life - I’m surrounded by them, and I earn my living from them. I can’t think of a world without poems or stories. Recently I was intrigued to

find scholars admitting that the fairy tales

they sometimes scoff at were many thousands of years old. It's taken them all that time to admit what was evident

even to the Brothers Grimm?

Archaeologists have long found evidence of major historical and geological events in our mythologies. Noah and the Flood is just one of them; the legend of Atlantis another. Telling stories is as old as human history, as old as language.

Tomorrow sees the launch of the Words by the Water festival of ‘Words and Ideas’ in Keswick. I’ve been invited to the launch party and look forward to meeting up with friends and fellow wordsmiths. Ten days of indulgent bookishness at the beautiful Theatre by the Lake. A glorious wallow in words - and scenery! If you can, do come - the Lake District needs every extra tourist it can find.

Lake Derwentwater from the Theatre by the Lake

Lake Derwentwater from the Theatre by the Lake

There’s non-fiction - Alice Jolly’s Dead Babies and Seaside Towns; poetry - Jane Hirshfield’s The Beauty, Grevel Lindop’s Luna Park, as well as collections by Margaret Atwood and Robert Hass; fiction includes Elena Ferrante (I’m half way through), Anne Enright, Tove Jansson and the wonderfully named ‘Manual for Cleaning Ladies’ by Lucia Berlin. My favourites so far are the Margaret Atwood poems; 'Morning in the Burned House', Tove Jansson's 'Winter Book', and a series of memoirs and reflections by NZ writer Kirsty Gunn; 'My Katherine Mansfield Project', which is really about exile and belonging. But as I read through the pile my preferences may change!

New text from the Epic of Gilgamesh discovered in Iraq - one of our earliest written stories.Books are my life - I’m surrounded by them, and I earn my living from them. I can’t think of a world without poems or stories. Recently I was intrigued to

find scholars admitting that the fairy tales

they sometimes scoff at were many thousands of years old. It's taken them all that time to admit what was evident

even to the Brothers Grimm?

Archaeologists have long found evidence of major historical and geological events in our mythologies. Noah and the Flood is just one of them; the legend of Atlantis another. Telling stories is as old as human history, as old as language.

New text from the Epic of Gilgamesh discovered in Iraq - one of our earliest written stories.Books are my life - I’m surrounded by them, and I earn my living from them. I can’t think of a world without poems or stories. Recently I was intrigued to

find scholars admitting that the fairy tales

they sometimes scoff at were many thousands of years old. It's taken them all that time to admit what was evident

even to the Brothers Grimm?

Archaeologists have long found evidence of major historical and geological events in our mythologies. Noah and the Flood is just one of them; the legend of Atlantis another. Telling stories is as old as human history, as old as language.

Tomorrow sees the launch of the Words by the Water festival of ‘Words and Ideas’ in Keswick. I’ve been invited to the launch party and look forward to meeting up with friends and fellow wordsmiths. Ten days of indulgent bookishness at the beautiful Theatre by the Lake. A glorious wallow in words - and scenery! If you can, do come - the Lake District needs every extra tourist it can find.

Lake Derwentwater from the Theatre by the Lake

Lake Derwentwater from the Theatre by the Lake

Published on March 03, 2016 06:14

March 1, 2016

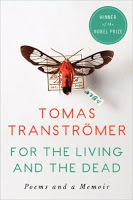

‘Six Winters,’ Tomas Tranströmer

1

In the black hotel a child is asleep.

And outside: the winter night

where the wide-eyed dice roll.

2

An élite of the dead became stone

in Katarina Churchyard

where the wind shakes in its armour from Svalbard.

3

One wartime winter when I lay sick

a huge icicle grew outside the window.

Neighbour and harpoon, unexplained memory.

4

Ice hangs down from the roof edge.

Icicles: the upside-down Gothic.

Abstract cattle, udders of glass.

5

On a side-track, an empty railway-carriage.

Still. Heraldic.

With the journeys in its claws.

6

Tonight snow-haze, moonlight. The moonlight jellyfish itself

is floating before us. Our smiles

on the way home. Bewitched avenue.

(trans. © Robin Fulton)

From 'För Levande och Döda', 1989.

Swedish poet Tomas Tranströmer loved writing haiku, and the three line poems above, though they don’t exactly fit the Japanese form, are clearly linked to it. Like much of Tranströmer’s work, the lines are stripped down to essentials and some of the images and ideas have to be teased out like riddles. They leave a huge space for the reader's imagination.

These winter memories are a child’s eye view of the world near the Arctic circle. The wind from one of the most northern inhabited islands - Svalbard - 'shakes in its armour' of immobilising cold. Icicles dangle from the gutters like harpoons or cow’s udders, ‘upside-down Gothic’; the poet wanders down a ‘bewitched avenue’ transformed by winter. I love the image of the moon as a jellyfish floating in the dark ocean of space. And the idea of the ‘elite dead’ also resonated with me; in England only the rich could afford headstones. The poor were buried either in unmarked graves, or with a wooden cross which quickly rotted away.

There’s an alternative translation of this sequence, by John F. Deane , but because Tranströmer writes in such a pared down way, there are only minor differences. He's a good poet to translate because he’s so precise and leaves little room for a translator’s personal interpretation. A couple of year's ago I translated a few of his poems, including 'Midwinter', and it was an instructive exercise. My favourite translations are by Robert Bly, who was a friend of the poet.

In the black hotel a child is asleep.

And outside: the winter night

where the wide-eyed dice roll.

2

An élite of the dead became stone

in Katarina Churchyard

where the wind shakes in its armour from Svalbard.

3

One wartime winter when I lay sick

a huge icicle grew outside the window.

Neighbour and harpoon, unexplained memory.

4

Ice hangs down from the roof edge.

Icicles: the upside-down Gothic.

Abstract cattle, udders of glass.

5

On a side-track, an empty railway-carriage.

Still. Heraldic.

With the journeys in its claws.

6

Tonight snow-haze, moonlight. The moonlight jellyfish itself

is floating before us. Our smiles

on the way home. Bewitched avenue.

(trans. © Robin Fulton)

From 'För Levande och Döda', 1989.

Swedish poet Tomas Tranströmer loved writing haiku, and the three line poems above, though they don’t exactly fit the Japanese form, are clearly linked to it. Like much of Tranströmer’s work, the lines are stripped down to essentials and some of the images and ideas have to be teased out like riddles. They leave a huge space for the reader's imagination.

These winter memories are a child’s eye view of the world near the Arctic circle. The wind from one of the most northern inhabited islands - Svalbard - 'shakes in its armour' of immobilising cold. Icicles dangle from the gutters like harpoons or cow’s udders, ‘upside-down Gothic’; the poet wanders down a ‘bewitched avenue’ transformed by winter. I love the image of the moon as a jellyfish floating in the dark ocean of space. And the idea of the ‘elite dead’ also resonated with me; in England only the rich could afford headstones. The poor were buried either in unmarked graves, or with a wooden cross which quickly rotted away.

There’s an alternative translation of this sequence, by John F. Deane , but because Tranströmer writes in such a pared down way, there are only minor differences. He's a good poet to translate because he’s so precise and leaves little room for a translator’s personal interpretation. A couple of year's ago I translated a few of his poems, including 'Midwinter', and it was an instructive exercise. My favourite translations are by Robert Bly, who was a friend of the poet.

Published on March 01, 2016 05:00

February 28, 2016

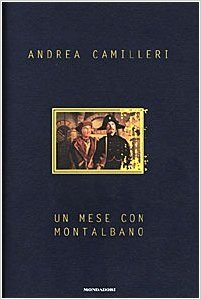

The Magic of Montalbano and Andrea Camilleri

I was addicted to the Sicilian detective before I ever went to Italy. What’s not to like? The scenery, the food, the characters, the complex plots - a detective torn always between the love of an unattainable woman and his own independence. Salvo Montalbano would like to be a faithful partner to the forceful Livia, who lives at the opposite end of the country, but he is an Italian man, an obsessive and morally driven policeman, both a cynic by experience and a romantic by nature (which probably sums up the entire national character of Italy).

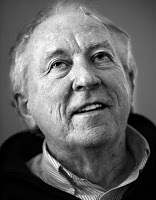

And then I love the covers - particularly the Italian ones with their matt black format. I’m OCD enough to long for a whole matching shelf of them! But for practicality I have them on my Kindle.

I recently watched the documentary about their author Andrea Camilleri (literary royalty in Italy) with great interest. He’s now 88 and has already written the last Montalbano book “just in case I get Alzheimers” and locked it in the vault. It was his grandmother who taught him to love stories, apparently, but he didn’t write his first novel until late, to keep a promise he made to his father just before he died. Montalbano's complicated relationship with his father in the novels, is rooted in Camilleri's relationship with his own father.

Camilleri was originally an actor, then a theatre director, then a lecturer in drama. All good training in the art of scene setting, creating dramatic tension and storytelling. His book shelves are lined with the greats of Italian drama, including a lot of Pirandello. Salvo Montalbano, Camilleri’s main character, is named after another great contemporary writer, Spanish poet, gastronome and detective author Vazquez Montalban, who died in 2003.

The TV adaptation of the novels (made by RAI in Italy) has been so successful because they have faithfully recreated the Sicilian world in which Montalbano operates, where crime solving is a case of the Art of the Possible, and ordinary people have to live beyond the law to survive. It is powerful families who control their communities and you have to be artful and cunning just to get by.

Luca Zingaretti, who plays Montalbano was a student of Camilleri’s and was coached by him when he auditioned for the role. Perfect casting for this particular reader. As is Fazio and the comic character Cattarella. I’ve always thought the screen character of Augello was a bit over-played, though he’s true to many Italian men I’ve met.

The Montalbano novels are a very happy addiction for me - they take me to a special place and into a world I love. Sicily, on a scorching summer day, the smell of dust, a whiff of goats, the dazzle of the Mediterranean, anchovies grilled in Parmesan, a glass of chilled white wine ....... Or, watching the sun go down and the lights begin to come on in one of those hill towns that seem hardly real.

Instead, on a cool February day in the Lake District, fuelled by English tea, I’ve been trying to reconstruct my flood-wrecked garden before the spring growth begins. Every shrub has been shrouded in debris from the river - dead leaves, fibrous material, string from hay bales, pieces of cloth, plastic. . . It feels good to be freeing them from their cauls. The fences have been torn down, so every shrub, every rose bush has to be pruned down almost to the ground so that they can be re-established once the fences have been rebuilt. The days are beginning to lighten, the sun is stronger when it shines. I can smell spring!

Published on February 28, 2016 08:09

February 16, 2016

Tuesday Poem: a Valentine's Day antidote - Margaret Cavendish, 1673

Oh Love, how thou art tired out with rhyme!

Thou art a tree whereon all poets climb;

And from thy branches every one takes some

Of thy sweet fruit, which Fancy feeds upon.

But now thy tree is left so bare and poor,

That they can hardly gather one plum more.

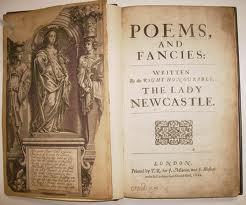

Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle, 1673

Not a great Romantic, our Margaret. But then, she had a tough life. Her family lost everything (including her brothers' lives) in the English Civil War. She married one of the most famous Cavaliers, the notorious womaniser William, Duke of Newcastle, and lived in exiled poverty until the Restoration of Charles II.

Margaret spent her time writing books - which was enough in the 17th century to ruin a woman's reputation. The King is reported to have said of her; 'Her Grace is an entire raree-show in her own person - a universal masquerade - indeed a sort of private Bedlam-hospital, her whole ideas being like so many patients crazed upon the subjects of love and literature . . .' Known as Mad Madge, or the Whore of Welbeck, she was a spectre to frighten clever, bookish girls with.

But she persevered and ignored her critics. 'It is also a great delight and pleasure to me, as being the only pastime which employs my idle hours insomuch that, were I sure nobody did read my works, yet I would not quit my pastime for all that, for although they should not delight others, yet they delight me.'

I found her a wonderful personality and a great inspiration. Her views were so ardently feminist, in an age when women had no freedom at all, I couldn't help but admire her audacity. 'True it is,' she wrote, anticipating Germaine Greer by several hundred years, 'that men from their first creation, usurped a supremacy to themselves, although we were made equal by nature, which tyrannical government they have kept ever since so that we could never come to be free, but rather more and more enslaved, using us either like children fools or subjects . . . and will not let us divide the World equally with them . . . which slavery hath so dejected our spirits, as we are become so stupid that Beasts are a degree below us, and men use us but a degree above beasts, whereas in Nature we have as clear an understanding as men; if we were bred in schools to mature our brains and to manure our understandings that we might bring forth the fruits of knowledge.'

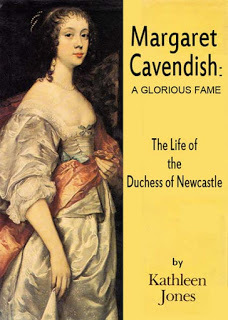

A Glorious Fame: The Life of Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle

Thou art a tree whereon all poets climb;

And from thy branches every one takes some

Of thy sweet fruit, which Fancy feeds upon.

But now thy tree is left so bare and poor,

That they can hardly gather one plum more.

Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle, 1673

Not a great Romantic, our Margaret. But then, she had a tough life. Her family lost everything (including her brothers' lives) in the English Civil War. She married one of the most famous Cavaliers, the notorious womaniser William, Duke of Newcastle, and lived in exiled poverty until the Restoration of Charles II.

Margaret spent her time writing books - which was enough in the 17th century to ruin a woman's reputation. The King is reported to have said of her; 'Her Grace is an entire raree-show in her own person - a universal masquerade - indeed a sort of private Bedlam-hospital, her whole ideas being like so many patients crazed upon the subjects of love and literature . . .' Known as Mad Madge, or the Whore of Welbeck, she was a spectre to frighten clever, bookish girls with.

But she persevered and ignored her critics. 'It is also a great delight and pleasure to me, as being the only pastime which employs my idle hours insomuch that, were I sure nobody did read my works, yet I would not quit my pastime for all that, for although they should not delight others, yet they delight me.'

I found her a wonderful personality and a great inspiration. Her views were so ardently feminist, in an age when women had no freedom at all, I couldn't help but admire her audacity. 'True it is,' she wrote, anticipating Germaine Greer by several hundred years, 'that men from their first creation, usurped a supremacy to themselves, although we were made equal by nature, which tyrannical government they have kept ever since so that we could never come to be free, but rather more and more enslaved, using us either like children fools or subjects . . . and will not let us divide the World equally with them . . . which slavery hath so dejected our spirits, as we are become so stupid that Beasts are a degree below us, and men use us but a degree above beasts, whereas in Nature we have as clear an understanding as men; if we were bred in schools to mature our brains and to manure our understandings that we might bring forth the fruits of knowledge.'

A Glorious Fame: The Life of Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle

Published on February 16, 2016 13:37

February 15, 2016

Reasons to be cheerful!

It's Valentine's Day, the sun is shining, the snowdrops are blooming ...... Time to smile, after a long and difficult winter. In my flood-wrecked garden, things are beginning to push upwards towards rumours of spring.

The moles have managed to survive being under 20 feet or more of raging flood water, and are digging themselves out again. This is one hell of a mole hill! It's a couple of feet across and a foot high.

Meanwhile, I've had another round of the Were-Wolf coughing virus, requiring days in bed and the ministrations of my lovely neighbour and the doctor. Currently a medical drug addict, but hoping to get out of rehab shortly! Life is too short to spend indoors with day-time TV (I have even watched Ice Road Truckers!). And I have a book to finish. 'Travelling to the Edge of the World' is now being trans-mogrified into html code, having illustrations added to it, and undergoing the painful process of editing to make it fit for Readers. It will soon, I hope, be ready to go out into the world, a couple of months later than scheduled, but I didn't allow for the power of the weather, or subversive viruses!

The moles have managed to survive being under 20 feet or more of raging flood water, and are digging themselves out again. This is one hell of a mole hill! It's a couple of feet across and a foot high.

Meanwhile, I've had another round of the Were-Wolf coughing virus, requiring days in bed and the ministrations of my lovely neighbour and the doctor. Currently a medical drug addict, but hoping to get out of rehab shortly! Life is too short to spend indoors with day-time TV (I have even watched Ice Road Truckers!). And I have a book to finish. 'Travelling to the Edge of the World' is now being trans-mogrified into html code, having illustrations added to it, and undergoing the painful process of editing to make it fit for Readers. It will soon, I hope, be ready to go out into the world, a couple of months later than scheduled, but I didn't allow for the power of the weather, or subversive viruses!

Published on February 15, 2016 13:56

February 9, 2016

Margaret Forster - a very private life

Saddened yesterday to learn of the death of Cumbrian author Margaret Forster. She had been looking cancer in the eye for more than forty years, after being diagnosed with breast cancer as a young mother. Although Margaret kept the diagnosis strictly private, the subject found its way, as writers' lives do, into her novels.

'Is there anything you want?'

is the story of a group of very different women who meet at a cancer clinic in a northern hospital that closely resembles the old Cumberland Infirmary in Carlisle. She didn't tell the full story, publicly, until her most recent book, a memoir, '

My Life in Houses

', written when secondary cancer had already invaded her spine.

Saddened yesterday to learn of the death of Cumbrian author Margaret Forster. She had been looking cancer in the eye for more than forty years, after being diagnosed with breast cancer as a young mother. Although Margaret kept the diagnosis strictly private, the subject found its way, as writers' lives do, into her novels.

'Is there anything you want?'

is the story of a group of very different women who meet at a cancer clinic in a northern hospital that closely resembles the old Cumberland Infirmary in Carlisle. She didn't tell the full story, publicly, until her most recent book, a memoir, '

My Life in Houses

', written when secondary cancer had already invaded her spine.

Margaret had no time for euphemisms. A spade was very definitely a spade, and her honesty sometimes terrified other people. No talk of 'passing away', or 'kicking the bucket' - 'What's wrong with the word "dead"?' Margaret asked. And she ridiculed those who talked about her brave 'battle' with cancer. 'There is no fighting that can be done,' she observed. 'and being positive not only has no proven effect but it creates another psychological burden for the patient.' She saw the illness as a 'touch of woodworm, or dry rot' in the house of the body - an insidious invasion that might never properly be eradicated. It takes courage to see things with such ruthless clarity.

It was a novel, a film, a musical and a hit single!Born and brought up in Cumbria, not far from where I was born, Margaret belonged to an older generation and her work was inspirational for younger writers. 'Georgy Girl' was a huge hit, both as a novel and a film. It was a big influence - I even have a daughter called Meredith Jones! Margaret and her husband Hunter Davies were, like myself, like Melvyn Bragg and many others, the product of a state education system that gave scholarships to working class children and enabled them to go on to university and enter the careers they dreamed of. Margaret's parents lived in a council house in one of the poorer areas of Carlisle. But she went to Oxford and became one of the UK's most successful novelists.

It was a novel, a film, a musical and a hit single!Born and brought up in Cumbria, not far from where I was born, Margaret belonged to an older generation and her work was inspirational for younger writers. 'Georgy Girl' was a huge hit, both as a novel and a film. It was a big influence - I even have a daughter called Meredith Jones! Margaret and her husband Hunter Davies were, like myself, like Melvyn Bragg and many others, the product of a state education system that gave scholarships to working class children and enabled them to go on to university and enter the careers they dreamed of. Margaret's parents lived in a council house in one of the poorer areas of Carlisle. But she went to Oxford and became one of the UK's most successful novelists.Margaret refused to compromise. Her life revolved around her family and her writing. She wasn't interested in the trappings of literary fame, though she did enjoy the financial benefits it brought. Publishers resigned themselves to the fact that she wouldn't go to literary festivals to promote her books. A little radio, magazine and newspaper articles, some photo-shoots and that had to be enough. Margaret didn't do literary dinner parties either and many thought her sharp-tongued and reclusive. As a new, rather self-conscious writer, I was terrified of her reputation. I remember being struck dumb on a public platform where I was supposed to be giving a talk, because someone told me that Margaret was sitting in the back row of the audience. When I actually met her, on another occasion, I was so tongue-tied I could barely stammer 'hello'. She must have thought me a complete idiot.

But the friends who knew her well loved her incisive mind (Hunter Davies says that she was the most intelligent woman he had ever known) and she was extraordinarily generous. I certainly found her so. She gave my book 'A Passionate Sisterhood' such a rave review, I still blush when I read it. When I asked for permission to re-write the short critical biography I had originally been commissioned by the Arts Council to write, to bring it up to date, she gave me unqualified permission and her only worry was that it might cost me money, since she wasn't a sufficiently famous author (in her eyes) to merit such a work. But it wasn't a question of money, more of recognition for a Cumbrian writer I had always believed to be critically under-rated.

Her best work, in my opinion, is her memoir writing - Hidden Lives and Precious Lives - the stories of her own family. They reveal, more expertly than anything else I have ever read, the difficulties and tragedies, and the sheer waste of talent, of what used to be called 'the servant class' in the days before the welfare state, when women in particular were at the mercy of unscrupulous employers. As we slide towards social inequality once more, books like this are worth reading as an awful reminder of what happens when we lose health care and education as a basic human right.

Margaret Forster will be much mourned by family, friends and readers alike. Our thoughts go out to her husband, Hunter Davies - a partnership both literary and personal that has lasted for more than 50 years - and to her three children.

Margaret Forster: A Life in Books

is published by The Book Mill

Published on February 09, 2016 06:32

February 4, 2016

Technical Hitches and Other Glitches

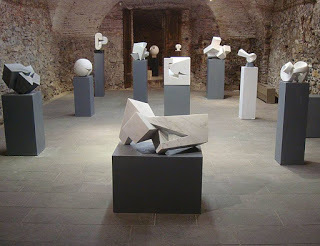

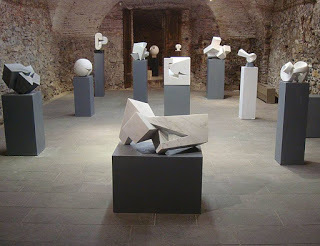

Jonah Jones does it again! No sooner do I arrive in Italy than the gas boiler takes one look at me and expires. 4 days without heating or hot water. I managed to endure that with reasonable fortitude (okay so I swore and used a lot of deodorant), but when I switched my computer on and it refused to obey, it was a major incident. Writers are dependent on technology; needing to work, committed to a monthly blog for Authors Electric, I was reduced to the basic communications of my mobile phone. I missed a couple of deadlines, but there was nothing I could do. Rural Italy is not the world centre of IT. It wasn't all doom and gloom though. Neil's exhibition looked wonderful and the opening party was spectacular. The President of the Commune made a speech and called him Maestro Ferber, celebrating a lifetime of skill and knowledge.

Who cares about technology when there's wine and music? And friends. The first diagnosis on the computer was that it was the boot drive - the screen flickered for a couple of seconds when I pressed the start button but then went blank. Nothing worked. There didn't seem to be a way to get into anything to even do a diagnostic test. I normally work on 'the cloud' so all my files were safe, but there's always a lot of things, mainly photographs, that you haven't backed up. I resigned myself to the loss. The culprit turned out to be a Windows update which had failed to load properly and corrupted the hard drive. Windows 10 is a nightmare - you have no control over what happens. It's Thursday night now (almost a week) and I'm back in the UK and up and running again, thanks to a partner who is not just a gifted sculptor, but a computer geek as well. Thank you Neil!

Neil and I before the hordes arrived, plus wine, minus computer.

Neil and I before the hordes arrived, plus wine, minus computer.

Who cares about technology when there's wine and music? And friends. The first diagnosis on the computer was that it was the boot drive - the screen flickered for a couple of seconds when I pressed the start button but then went blank. Nothing worked. There didn't seem to be a way to get into anything to even do a diagnostic test. I normally work on 'the cloud' so all my files were safe, but there's always a lot of things, mainly photographs, that you haven't backed up. I resigned myself to the loss. The culprit turned out to be a Windows update which had failed to load properly and corrupted the hard drive. Windows 10 is a nightmare - you have no control over what happens. It's Thursday night now (almost a week) and I'm back in the UK and up and running again, thanks to a partner who is not just a gifted sculptor, but a computer geek as well. Thank you Neil!

Neil and I before the hordes arrived, plus wine, minus computer.

Neil and I before the hordes arrived, plus wine, minus computer.

Published on February 04, 2016 13:31