Kathleen Jones's Blog, page 19

August 13, 2016

Gone AWOL - Normal service to be resumed soon

I'm on holiday - having a much needed break. No beach, I'm afraid. This is a stay-cation with children and grandchildren coming to me for a big family party. So I won't be around much over the next couple of weeks. Have a great summer holiday everyone!

Thanks to Julia Smith, librarian, at Cover to Cover for the pic - it's a great YA site from KeriKeri High School in New Zealand and has an E-book library. Take a look !

Thanks to Julia Smith, librarian, at Cover to Cover for the pic - it's a great YA site from KeriKeri High School in New Zealand and has an E-book library. Take a look !

Published on August 13, 2016 14:40

August 4, 2016

Haida Gwaii and the Masters of the Pacific Coast

I've thoroughly enjoyed the BBC4 documentary programme on the First Nation people of the Pacific Coast of the US, Canada and Alaska. The British Museum's Dr Jago Cooper made the same journey, both physical and historical, that I made last year in search of a people who have managed to survive for more than 10,000 years in the same environment without destroying it. Very few other cultures have succeeded in doing that - most of them have been wiped out by Western 'incomers' who regarded their own cultures as 'advanced' and superior. That's a viewpoint that has succeeded in polluting and exploiting the entire planet.

The Mortuary and Memorial poles of Ninstints, Haida GwaiiWatching Jago Cooper canoeing round the coastal inlets and tramping through ancient woodlands made me very nostalgic for Haida Gwaii, Cormorant Island and the many other places I visited. I longed to go back. He met many of the people I met too - Haida artists and carvers, museum curators. But he stayed well clear of the politics. The daily fight for their landrights against oil companies and forestry corporations was barely touched on. But he did, in Programme 2, confront the genocide perpetrated by the government of British Columbia which left only 500 out of 30,000 people on Haida Gwaii alive. It is a tribute to the strength of their culture that they survived. As their declaration in the preamble to the Haida Constitution affirms:

The Mortuary and Memorial poles of Ninstints, Haida GwaiiWatching Jago Cooper canoeing round the coastal inlets and tramping through ancient woodlands made me very nostalgic for Haida Gwaii, Cormorant Island and the many other places I visited. I longed to go back. He met many of the people I met too - Haida artists and carvers, museum curators. But he stayed well clear of the politics. The daily fight for their landrights against oil companies and forestry corporations was barely touched on. But he did, in Programme 2, confront the genocide perpetrated by the government of British Columbia which left only 500 out of 30,000 people on Haida Gwaii alive. It is a tribute to the strength of their culture that they survived. As their declaration in the preamble to the Haida Constitution affirms:

'Our culture is born of respect and intimacy with the land and sea and the air around us. Like the forest, the roots of our people are intertwined such that the greatest troubles cannot over come us.'

Jago CooperThere's a very good review of the programme over at

The Arts Desk

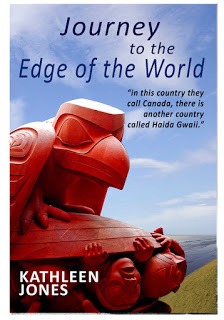

. I will be watching the repeats too, feeding my longing to return to the lands of the Haida Nation, the Tlingit and the Coastal Salish. For anyone who wants to read more (with full colour illustrations) about the people of the Pacific Coast, my book,

Travelling to the Edge of the World,

is available through Amazon and to be ordered from all good bookshops. It can also be purchased by emailing thebookmill@ferberjones.com for £9.00 + P&P

Jago CooperThere's a very good review of the programme over at

The Arts Desk

. I will be watching the repeats too, feeding my longing to return to the lands of the Haida Nation, the Tlingit and the Coastal Salish. For anyone who wants to read more (with full colour illustrations) about the people of the Pacific Coast, my book,

Travelling to the Edge of the World,

is available through Amazon and to be ordered from all good bookshops. It can also be purchased by emailing thebookmill@ferberjones.com for £9.00 + P&P

The Mortuary and Memorial poles of Ninstints, Haida GwaiiWatching Jago Cooper canoeing round the coastal inlets and tramping through ancient woodlands made me very nostalgic for Haida Gwaii, Cormorant Island and the many other places I visited. I longed to go back. He met many of the people I met too - Haida artists and carvers, museum curators. But he stayed well clear of the politics. The daily fight for their landrights against oil companies and forestry corporations was barely touched on. But he did, in Programme 2, confront the genocide perpetrated by the government of British Columbia which left only 500 out of 30,000 people on Haida Gwaii alive. It is a tribute to the strength of their culture that they survived. As their declaration in the preamble to the Haida Constitution affirms:

The Mortuary and Memorial poles of Ninstints, Haida GwaiiWatching Jago Cooper canoeing round the coastal inlets and tramping through ancient woodlands made me very nostalgic for Haida Gwaii, Cormorant Island and the many other places I visited. I longed to go back. He met many of the people I met too - Haida artists and carvers, museum curators. But he stayed well clear of the politics. The daily fight for their landrights against oil companies and forestry corporations was barely touched on. But he did, in Programme 2, confront the genocide perpetrated by the government of British Columbia which left only 500 out of 30,000 people on Haida Gwaii alive. It is a tribute to the strength of their culture that they survived. As their declaration in the preamble to the Haida Constitution affirms:'Our culture is born of respect and intimacy with the land and sea and the air around us. Like the forest, the roots of our people are intertwined such that the greatest troubles cannot over come us.'

Jago CooperThere's a very good review of the programme over at

The Arts Desk

. I will be watching the repeats too, feeding my longing to return to the lands of the Haida Nation, the Tlingit and the Coastal Salish. For anyone who wants to read more (with full colour illustrations) about the people of the Pacific Coast, my book,

Travelling to the Edge of the World,

is available through Amazon and to be ordered from all good bookshops. It can also be purchased by emailing thebookmill@ferberjones.com for £9.00 + P&P

Jago CooperThere's a very good review of the programme over at

The Arts Desk

. I will be watching the repeats too, feeding my longing to return to the lands of the Haida Nation, the Tlingit and the Coastal Salish. For anyone who wants to read more (with full colour illustrations) about the people of the Pacific Coast, my book,

Travelling to the Edge of the World,

is available through Amazon and to be ordered from all good bookshops. It can also be purchased by emailing thebookmill@ferberjones.com for £9.00 + P&P

Published on August 04, 2016 10:53

August 1, 2016

Tuesday Poem: No News by Kathleen Jones

On this day

the sun shone on Eden

and the river gave back the light.

On this day

there were eight ducklings

instead of twelve. A feathered flotilla

under the willows where the hooked jaws

of the pike dapple in deep water.

On this day

a politician confessed

to falsifying his accounts and another

to being unfaithful to the electorate.

I have sinned, he said. It will never happen again.

On this day

a trillion dollars

found its way into a secret account

on a distant island where there are no politics

that are not to do with money.

On this day

six fighter jets, twenty tanks and

a hundred assault rifles were delivered

across an unmarked border.

On this day

two football teams escaped relegation

and a banker was cleared of corruption.

The real ale in the pub had the regulation amount of froth.

On this day

four hundred men, women and children drowned

in the Mediterranean, fleeing conflict.

On this day

the magnolia opened its white petals

for the first time and there is a wren nesting

above the door in the hole I drilled

for a lamp bracket. I called my mother.

She was not at home.

Copyright Kathleen Jones, 2016

Every now and then I try to make sense of things - this contradictory, tragic, beautiful, upside-down world we live in. I wrote this poem on one of those days - just an ordinary day. Out shopping I overheard someone say there was 'no news today', meaning presumably that there was nothing new on the news that hadn't been on before. It made me angry and set me thinking. It's times like this I miss my mother - she and I would talk for hours on the phone about life and politics and how we felt and how could we deal with the kind of emotions aroused by the terrible scenes beamed into our living rooms by the media. I still know her telephone number by heart and occasionally I give in to the temptation to ring it, though I know there is no-one there. Anyone else do crazy things like this?

the sun shone on Eden

and the river gave back the light.

On this day

there were eight ducklings

instead of twelve. A feathered flotilla

under the willows where the hooked jaws

of the pike dapple in deep water.

On this day

a politician confessed

to falsifying his accounts and another

to being unfaithful to the electorate.

I have sinned, he said. It will never happen again.

On this day

a trillion dollars

found its way into a secret account

on a distant island where there are no politics

that are not to do with money.

On this day

six fighter jets, twenty tanks and

a hundred assault rifles were delivered

across an unmarked border.

On this day

two football teams escaped relegation

and a banker was cleared of corruption.

The real ale in the pub had the regulation amount of froth.

On this day

four hundred men, women and children drowned

in the Mediterranean, fleeing conflict.

On this day

the magnolia opened its white petals

for the first time and there is a wren nesting

above the door in the hole I drilled

for a lamp bracket. I called my mother.

She was not at home.

Copyright Kathleen Jones, 2016

Every now and then I try to make sense of things - this contradictory, tragic, beautiful, upside-down world we live in. I wrote this poem on one of those days - just an ordinary day. Out shopping I overheard someone say there was 'no news today', meaning presumably that there was nothing new on the news that hadn't been on before. It made me angry and set me thinking. It's times like this I miss my mother - she and I would talk for hours on the phone about life and politics and how we felt and how could we deal with the kind of emotions aroused by the terrible scenes beamed into our living rooms by the media. I still know her telephone number by heart and occasionally I give in to the temptation to ring it, though I know there is no-one there. Anyone else do crazy things like this?

Published on August 01, 2016 15:30

Climate Change and Katherine Mansfield

In 1907, more than a hundred years ago, Katherine Mansfield's father, Harold Beauchamp, bought what is called in New Zealand a 'bach' (pronounced batch) beside the sea. It was a plain, wooden building without any creature comforts, described as having a 'small poverty stricken sitting room . . . A cabin-like bedroom fitted with bunks, and an outhouse with a bath, and wood cellar, coal cellar, complete.' Behind it, oddly at the back of the original house, the sea lapped over the rocks, and at the front wild bush grew down to the narrow track that served as a road.

The bach is in a beautiful hamlet called Days Bay. It's one of the inlets across the water from Wellington and you can visit it using the ferry that takes commuters and school children from village to city every day. In 1907 it was more a summer retreat for weekends and the children's holidays. Katherine loved being there, and her story 'At The Bay' conveys the atmosphere of holiday, of being close to the wilderness, ocean and sky, and the influence of that release from the usual disciplines of polite behaviour on her characters. The opening of the story describes the place and the atmosphere, perfectly.

‘Very early morning. The sun was not yet risen, and the whole of Crescent Bay was hidden under a white sea mist. The big, bush-covered hills at the back were smothered. You could not see where they ended and the paddocks and bungalows began. The sandy road was gone and the paddocks and bungalows the other side of it; there were no white dunes covered with reddish grass beyond them; there was nothing to mark which was beach and where was the sea.’

It was at Day's Bay, in the little chalet, that Katherine had what was possibly her first experience of female sexuality. She was staying there with an older woman, an artist, Edith Bendall, and Katherine was in love with her and hoped that it would be reciprocated. 'I cannot lie in my bed and not feel the magic of her body . . . She enthrals, enslaves me.' Katherine suffered from night terrors and terrible dreams. Outside the darkness and the bush beyond set her imagination racing 'until the very fence became terrible.' The fence posts became 'hideous forms' gesticulating and taking on human appearance. Edith takes her into her bed to comfort her and then, Katherine writes, 'a thousand things which had been obscure' become plain. It was her 'Oscar Wilde' moment. But Edith was unresponsive, perhaps aware that Katherine's parents were relying on her to look after the younger girl. Katherine was attracted by both men and women for the rest of her short life.

Wellington, despite being in a sheltered harbour, is famous for its storms, but Days Bay and the beach-side houses have always been safe. The worst storm in 117 years had only broken a window. But in 2013 a mega-storm wreaked unprecedented destruction. The little cottage, now altered for modern use, but still a site of pilgrimage for Mansfield readers, was almost completely destroyed. The current owners described a night of terror. "My dad got up at about 12.45am after he heard a window smash. He went to the front door to get a piece of plywood and saw there was a lot of water building up around the house. He went back inside to get Mum, and a huge wave took out the dining room window, so they grabbed the dogs and made a run for it to the neighbours." When they came back next morning, “pretty much everything had been washed out by the sea.” This is what it looked like.

For a long time it was thought that the cottage would just be bulldozed. I visited in 2014 and it looked too damaged to be viable. But there was a big campaign to raise money for one of Wellington's historic buildings to be rebuilt, and it has now been restored, though with an altered beach-front to help it withstand more big storms.

Despite that, there are a lot of people in Wellington who feel that, with the increasing frequency of mega-storms, the cottage remains vulnerable. Climate change, and projected sea-level increase, could make such properties uninhabitable.

Katherine Mansfield's story 'At the Bay' (pdf)

If you like Katherine Mansfield you might also be interested in ' Katherine Mansfield - The Storyteller' by Kathleen Jones

The Katherine Mansfield Society has a wonderful website, full of photographs and information, well worth a visit.

My friend Gerri Kimber has a biography of Katherine Mansfield's early years in New Zealand coming out in October 2016.

The bach is in a beautiful hamlet called Days Bay. It's one of the inlets across the water from Wellington and you can visit it using the ferry that takes commuters and school children from village to city every day. In 1907 it was more a summer retreat for weekends and the children's holidays. Katherine loved being there, and her story 'At The Bay' conveys the atmosphere of holiday, of being close to the wilderness, ocean and sky, and the influence of that release from the usual disciplines of polite behaviour on her characters. The opening of the story describes the place and the atmosphere, perfectly.

‘Very early morning. The sun was not yet risen, and the whole of Crescent Bay was hidden under a white sea mist. The big, bush-covered hills at the back were smothered. You could not see where they ended and the paddocks and bungalows began. The sandy road was gone and the paddocks and bungalows the other side of it; there were no white dunes covered with reddish grass beyond them; there was nothing to mark which was beach and where was the sea.’

It was at Day's Bay, in the little chalet, that Katherine had what was possibly her first experience of female sexuality. She was staying there with an older woman, an artist, Edith Bendall, and Katherine was in love with her and hoped that it would be reciprocated. 'I cannot lie in my bed and not feel the magic of her body . . . She enthrals, enslaves me.' Katherine suffered from night terrors and terrible dreams. Outside the darkness and the bush beyond set her imagination racing 'until the very fence became terrible.' The fence posts became 'hideous forms' gesticulating and taking on human appearance. Edith takes her into her bed to comfort her and then, Katherine writes, 'a thousand things which had been obscure' become plain. It was her 'Oscar Wilde' moment. But Edith was unresponsive, perhaps aware that Katherine's parents were relying on her to look after the younger girl. Katherine was attracted by both men and women for the rest of her short life.

Wellington, despite being in a sheltered harbour, is famous for its storms, but Days Bay and the beach-side houses have always been safe. The worst storm in 117 years had only broken a window. But in 2013 a mega-storm wreaked unprecedented destruction. The little cottage, now altered for modern use, but still a site of pilgrimage for Mansfield readers, was almost completely destroyed. The current owners described a night of terror. "My dad got up at about 12.45am after he heard a window smash. He went to the front door to get a piece of plywood and saw there was a lot of water building up around the house. He went back inside to get Mum, and a huge wave took out the dining room window, so they grabbed the dogs and made a run for it to the neighbours." When they came back next morning, “pretty much everything had been washed out by the sea.” This is what it looked like.

For a long time it was thought that the cottage would just be bulldozed. I visited in 2014 and it looked too damaged to be viable. But there was a big campaign to raise money for one of Wellington's historic buildings to be rebuilt, and it has now been restored, though with an altered beach-front to help it withstand more big storms.

Despite that, there are a lot of people in Wellington who feel that, with the increasing frequency of mega-storms, the cottage remains vulnerable. Climate change, and projected sea-level increase, could make such properties uninhabitable.

Katherine Mansfield's story 'At the Bay' (pdf)

If you like Katherine Mansfield you might also be interested in ' Katherine Mansfield - The Storyteller' by Kathleen Jones

The Katherine Mansfield Society has a wonderful website, full of photographs and information, well worth a visit.

My friend Gerri Kimber has a biography of Katherine Mansfield's early years in New Zealand coming out in October 2016.

Published on August 01, 2016 09:38

July 26, 2016

Tuesday Poem: 'A Whole Day Through from Waking', by Jacci Bulman

A whole day through from waking -

allowing love.

Halt has been called,

by whom? we forget.

It came like a heron to the river.

My bitch is set free,

(barked as far as Mars,

bit the air like a jackal).

His rats are scattered.

Now we sit quiet by the water,

he watches the deep pool for fish,

I look at his lips and

watch only that part of him.

Copyright Jacci Bulman 2016

A Whole Day Through From Waking , Cinnamon Press, 2016

This is the title poem of Jacci Bulman's first collection. It seems to describe the quiet moment after a quarrel. Rats and terriers have gone, the heron has glided into place beside the river and the two lovers sit watching it, but with a new awareness of each other. This is how the poem feels to me, but it may resonate differently with other people.

This is the title poem of Jacci Bulman's first collection. It seems to describe the quiet moment after a quarrel. Rats and terriers have gone, the heron has glided into place beside the river and the two lovers sit watching it, but with a new awareness of each other. This is how the poem feels to me, but it may resonate differently with other people.

These poems celebrate the small epiphanies of everyday living. 'Last night we watched a film,/ you stroked my feet,/ we ate peppermint creams', sounds very ordinary, but the memory is recalled in a hospital waiting room - a context that gives it a very different meaning. Life is precarious - in the midst of the ordinary, we are pitched into the extraordinary. Context and hindsight change our perspective. Small domestic tasks bring relief to the chaos of life because of their very ordinariness. A poem titled 'Evening after a disaster at work' begins: 'The fat tadpoles are a relief./ She peers down/ at their attempts to grab pond-weed,/ new legs taking a rest on submerged reed.' The surface of the poem, like the 'skin of the pond', has secret depths. The dangers that the frogs and tadpoles have to cope with - life and death issues - put the poet's own tribulations into perspective. These are deceptively simple poems. Jacci Bulman is one of the north's new voices and her take on life is informed by her own private struggle with a brain tumour while a student at Oxford University. She writes obliquely about darkness, obeying Emily Dickinson's advice:

Tell all the truth but tell it slant —

Success in Circuit lies

Too bright for our infirm Delight

The Truth's superb surprise . . .

These aren't wildly intellectual poems, but the quiet narratives of everyday. I like that.

A Whole Day Through from Waking

by Jacci Bulman £8.99

Cinnamon Press 2016

Quotes from reader reviews:

"This is poetry that is open-hearted, that reaches out to its audience with open arms. It is the kind of poetry which poets and non-poets alike can appreciate; it doesn’t buy into poetry snobbery or elitism, but also it never shies away from looking life full in the face."

" The work is sometimes an ode to the every day, the things we take for granted that retrospectively we may yearn for. This is the poetry of staying in the present, recognising the blissful beauty of life itself be it strewn with pain, sorrow, worry or joy. It is a generous book offering the reader a glimpse into the world of the author in whom we recognise aspects of our secret selves."

"Reading this book was like drinking a sparkling elderflower champagne, light and airy, yet born of earth. It is wonderful. I always enjoy poems that are taken from the lives we live, which offer every kind of subject imaginable."

"Jacci Bulman's work addresses the big questions and issues in life. It is shot through with love"

allowing love.

Halt has been called,

by whom? we forget.

It came like a heron to the river.

My bitch is set free,

(barked as far as Mars,

bit the air like a jackal).

His rats are scattered.

Now we sit quiet by the water,

he watches the deep pool for fish,

I look at his lips and

watch only that part of him.

Copyright Jacci Bulman 2016

A Whole Day Through From Waking , Cinnamon Press, 2016

This is the title poem of Jacci Bulman's first collection. It seems to describe the quiet moment after a quarrel. Rats and terriers have gone, the heron has glided into place beside the river and the two lovers sit watching it, but with a new awareness of each other. This is how the poem feels to me, but it may resonate differently with other people.

This is the title poem of Jacci Bulman's first collection. It seems to describe the quiet moment after a quarrel. Rats and terriers have gone, the heron has glided into place beside the river and the two lovers sit watching it, but with a new awareness of each other. This is how the poem feels to me, but it may resonate differently with other people.These poems celebrate the small epiphanies of everyday living. 'Last night we watched a film,/ you stroked my feet,/ we ate peppermint creams', sounds very ordinary, but the memory is recalled in a hospital waiting room - a context that gives it a very different meaning. Life is precarious - in the midst of the ordinary, we are pitched into the extraordinary. Context and hindsight change our perspective. Small domestic tasks bring relief to the chaos of life because of their very ordinariness. A poem titled 'Evening after a disaster at work' begins: 'The fat tadpoles are a relief./ She peers down/ at their attempts to grab pond-weed,/ new legs taking a rest on submerged reed.' The surface of the poem, like the 'skin of the pond', has secret depths. The dangers that the frogs and tadpoles have to cope with - life and death issues - put the poet's own tribulations into perspective. These are deceptively simple poems. Jacci Bulman is one of the north's new voices and her take on life is informed by her own private struggle with a brain tumour while a student at Oxford University. She writes obliquely about darkness, obeying Emily Dickinson's advice:

Tell all the truth but tell it slant —

Success in Circuit lies

Too bright for our infirm Delight

The Truth's superb surprise . . .

These aren't wildly intellectual poems, but the quiet narratives of everyday. I like that.

A Whole Day Through from Waking

by Jacci Bulman £8.99

Cinnamon Press 2016

Quotes from reader reviews:

"This is poetry that is open-hearted, that reaches out to its audience with open arms. It is the kind of poetry which poets and non-poets alike can appreciate; it doesn’t buy into poetry snobbery or elitism, but also it never shies away from looking life full in the face."

" The work is sometimes an ode to the every day, the things we take for granted that retrospectively we may yearn for. This is the poetry of staying in the present, recognising the blissful beauty of life itself be it strewn with pain, sorrow, worry or joy. It is a generous book offering the reader a glimpse into the world of the author in whom we recognise aspects of our secret selves."

"Reading this book was like drinking a sparkling elderflower champagne, light and airy, yet born of earth. It is wonderful. I always enjoy poems that are taken from the lives we live, which offer every kind of subject imaginable."

"Jacci Bulman's work addresses the big questions and issues in life. It is shot through with love"

Published on July 26, 2016 05:15

July 25, 2016

Masters of the Pacific Coast - the BBC travels to the Edge of the World

The BBC are finally devoting 2 programmes to the First Nation people of the northernmost coastline of British Columbia and Alaska, including Haida Gwaii. Dr Jago Cooper is the narrator for

Masters of the Pacific Coast,

the first of 2 programmes beginning on Wednesday 28th July at 9pm (British Summer Time). Worth watching, I hope. (And if you're really interested you could just

read my book

which is now out in paperback!)

You can get it new in paperback for as little as £9.83 via Amazon.

Kindle edition £3.99

You can get it new in paperback for as little as £9.83 via Amazon.

Kindle edition £3.99

Published on July 25, 2016 04:47

July 24, 2016

Summer Reading: The Trysting Tree by Linda Gillard

I've been saving some good reads for the summer - books to lose yourself in - books for a good wallow, and

The Trysting Tree

is one of them. I've long been a fan of

Linda Gillard's

fiction - they're beautifully constructed, intelligent, well-written novels with unusual plots and stunning locations. If I had to categorise them, I suppose I'd have to put them into the romantic literary fiction genre. But, although there is always a love story (in this case more than one) in the novel, there is often a great deal of psychological angst too. She has written about post-traumatic-stress disorder, grief, depression, incest and the difficulties of dysfunctional families. Some of her novels stray towards the Gothic - dilapidated Scottish castles with ghosts, or crumbling mansions. I've enjoyed them all.

I've been saving some good reads for the summer - books to lose yourself in - books for a good wallow, and

The Trysting Tree

is one of them. I've long been a fan of

Linda Gillard's

fiction - they're beautifully constructed, intelligent, well-written novels with unusual plots and stunning locations. If I had to categorise them, I suppose I'd have to put them into the romantic literary fiction genre. But, although there is always a love story (in this case more than one) in the novel, there is often a great deal of psychological angst too. She has written about post-traumatic-stress disorder, grief, depression, incest and the difficulties of dysfunctional families. Some of her novels stray towards the Gothic - dilapidated Scottish castles with ghosts, or crumbling mansions. I've enjoyed them all.We've just passed the anniversary of the Battle of the Somme, and The Trysting Tree has, at the centre of the book, a tragedy born from World War I. Part of the plot involves the unraveling of letters and family history to solve a mystery. But the heroine, Ann de Freitas, also has a mystery at the heart of her own life, concerning her absent father - why did he leave so abruptly? Where is he now? And why will her mother not talk about it?

I knew from Linda's Facebook page that she was working on this book, but what I didn't know was that Linda had chosen a portrait by a very good friend of mine, Norwegian painter Dora Bendixon, for her 'prompt' for the character of one of the protagonists - Ann's mother, the difficult, egotistical, complicated artist Phoebe Flint.

When Linda loaded the image onto Facebook it was the most astonishing coincidence, as I'd just been standing beside that painting in Dora's living room in Italy (artists do get about a bit!). The portrait is, by another strange coincidence, that of a famous Brazilian-born sculptor called Eugenia Wolfowicz, who was every bit as eccentric as Phoebe Flint.

The Trysting Tree is a very good novel to read beside the pool on a warm summer afternoon - or in any other location for that matter. I read it on the sofa on a grey, rainy day in what passes for summer in the Lake District. All Linda's novels come highly recommended, though I have to confess that House of Silence is still my all-time favourite!

The Trysting Tree in only available as an e-book at the moment - paperback out in September.

Linda Gillard's website

Published on July 24, 2016 13:42

July 19, 2016

Tuesday Poem: In Parenthesis, by David Jones

In Parenthesis – Part 7,

pages 183-186

It’s difficult with the weight of the rifle.

Leave it–under the oak.

Leave it for a salvage-bloke

let it lie bruised for a monument

dispense the authenticated fragments to the faithful.

It’s the thunder-besom for us

it’s the bright bough borne

it’s the tensioned yew for a Genoese jammed arbalest and a

scarlet square for a mounted mareschal, it’s that county-mob

back to back. Majuba mountain and Mons Cherubim and

spreaded mats for Sydney Street East, and come to Bisley

for a Silver Dish. It’s R.S.M. O’Grady says, it’s the soldier’s

best friend if you care for the working parts and let us be ‘av-

ing those springs released smartly in Company billets on wet

forenoons and clickerty-click and one up the spout and you

men must really cultivate the habit of treating this weapon with

the very greatest care and there should be a healthy rivalry

among you–it should be a matter of very proper pride and

Marry it man! Marry it!

Cherish her, she’s your very own.

Coax it man coax it–it’s delicately and ingeniously made

–it’s an instrument of precision–it costs us tax-payers,

money–I want you men to remember that.

Fondle it like a granny–talk to it–consider it as you would

a friend–and when you ground these arms she’s not a rooky’s

gas-pipe for greenhorns to tarnish.

You’ve known her hot and cold.

You would choose her from among many.

You know her by her bias, and by her exact error at 300, and

by the deep scar at the small, by the fair flaw in the grain,

above the lower sling-swivel–

but leave it under the oak.

Slung so, it swings its full weight. With you going blindly on

all paws, it slews its whole length, to hang at your bowed neck

like the Mariner’s white oblation.

You drag past the four bright stones at the turn of Wood

Support.

It is not to be broken on the brown stone under the gracious

tree.

It is not to be hidden under your failing body.

Slung so, it troubles your painful crawling like a fugitive’s

irons.

(1937)

David Jones

There is nothing else like David Jones' epic poem of war 'In Parenthesis'. It was written in 1937, looking back at the horrors of WWI, as WW2 loomed ahead. David Jones was wounded in the Battle of the Somme, so I thought it appropriate to post a fragment of a much neglected poem just as we are all remembering the anniversary.

David Jones was both a poet and a painter and he was one of the wartime proteges of a wealthy philanthropist called Helen Sutherland who owned a mansion overlooking Lake Ullswater and at various times hosted poets and artists such as Norman Nicholson, Winifred and Ben Nicholson (no relation), Kathleen Raine, Elizabeth Jennings and David Jones. David was in poor health; he suffered from 'nerves' and apparently almost had a breakdown over a bottle of spilt ink in the bedroom of Sutherland's dauntingly exquisite house.

In Parenthesis was broadcast on the BBC Third Programme in 1946. Recently is has been made into an opera for the Welsh National Opera, broadcast by the BBC, which also made a documentary film about it. You can just catch it on iPlayer if you click here. And the poet Owen Sheers made a magical documentary about the poem he calls 'the greatest poem of WWI', which is also available on iPlayer here.

pages 183-186

It’s difficult with the weight of the rifle.

Leave it–under the oak.

Leave it for a salvage-bloke

let it lie bruised for a monument

dispense the authenticated fragments to the faithful.

It’s the thunder-besom for us

it’s the bright bough borne

it’s the tensioned yew for a Genoese jammed arbalest and a

scarlet square for a mounted mareschal, it’s that county-mob

back to back. Majuba mountain and Mons Cherubim and

spreaded mats for Sydney Street East, and come to Bisley

for a Silver Dish. It’s R.S.M. O’Grady says, it’s the soldier’s

best friend if you care for the working parts and let us be ‘av-

ing those springs released smartly in Company billets on wet

forenoons and clickerty-click and one up the spout and you

men must really cultivate the habit of treating this weapon with

the very greatest care and there should be a healthy rivalry

among you–it should be a matter of very proper pride and

Marry it man! Marry it!

Cherish her, she’s your very own.

Coax it man coax it–it’s delicately and ingeniously made

–it’s an instrument of precision–it costs us tax-payers,

money–I want you men to remember that.

Fondle it like a granny–talk to it–consider it as you would

a friend–and when you ground these arms she’s not a rooky’s

gas-pipe for greenhorns to tarnish.

You’ve known her hot and cold.

You would choose her from among many.

You know her by her bias, and by her exact error at 300, and

by the deep scar at the small, by the fair flaw in the grain,

above the lower sling-swivel–

but leave it under the oak.

Slung so, it swings its full weight. With you going blindly on

all paws, it slews its whole length, to hang at your bowed neck

like the Mariner’s white oblation.

You drag past the four bright stones at the turn of Wood

Support.

It is not to be broken on the brown stone under the gracious

tree.

It is not to be hidden under your failing body.

Slung so, it troubles your painful crawling like a fugitive’s

irons.

(1937)

David Jones

There is nothing else like David Jones' epic poem of war 'In Parenthesis'. It was written in 1937, looking back at the horrors of WWI, as WW2 loomed ahead. David Jones was wounded in the Battle of the Somme, so I thought it appropriate to post a fragment of a much neglected poem just as we are all remembering the anniversary.

David Jones was both a poet and a painter and he was one of the wartime proteges of a wealthy philanthropist called Helen Sutherland who owned a mansion overlooking Lake Ullswater and at various times hosted poets and artists such as Norman Nicholson, Winifred and Ben Nicholson (no relation), Kathleen Raine, Elizabeth Jennings and David Jones. David was in poor health; he suffered from 'nerves' and apparently almost had a breakdown over a bottle of spilt ink in the bedroom of Sutherland's dauntingly exquisite house.

In Parenthesis was broadcast on the BBC Third Programme in 1946. Recently is has been made into an opera for the Welsh National Opera, broadcast by the BBC, which also made a documentary film about it. You can just catch it on iPlayer if you click here. And the poet Owen Sheers made a magical documentary about the poem he calls 'the greatest poem of WWI', which is also available on iPlayer here.

Published on July 19, 2016 14:55

July 17, 2016

Sunday Book: Dead Babies and Seaside Towns by Alice Jolly

This book arrived on my doorstep (literally – it was too big to go through the letterbox) months ago, at a time when I was overwhelmed with work. Then the floods wrecked the house and interrupted my life and it is only recently that I have finally opened the covers to read Alice Jolly’s memoir,

Dead Babies and Seaside Towns

. Since then the book has begun to win awards, including most recently the prestigious

PEN Ackerley Prize

, beating AA Gill and Adam Mars Jones to the money.

This book arrived on my doorstep (literally – it was too big to go through the letterbox) months ago, at a time when I was overwhelmed with work. Then the floods wrecked the house and interrupted my life and it is only recently that I have finally opened the covers to read Alice Jolly’s memoir,

Dead Babies and Seaside Towns

. Since then the book has begun to win awards, including most recently the prestigious

PEN Ackerley Prize

, beating AA Gill and Adam Mars Jones to the money. This is a book I’ve been close to. Alice and I both tutored for the Open University’s creative writing degree course and became friends. There was other shared experience; I have two stillborn grandchildren and, observing the pain and darkness my children went through with their beautiful dead babies, gave me some tiny morsel of understanding of the rage and grief that Alice was experiencing as she longed for the child she could not have. No one, who has not experienced it (and even some women claim not to have done so), can imagine the power of the biological urge to have a child, the consuming, savage desire to hold a baby in your arms, feel its soft skin against your own, smell the arresting odour of the newborn. The pain of loss is crippling, mentally and physically. It destroys relationships with partners, siblings, relatives and friends. Alice quotes the poet W.S. Merwin:

‘Your absence has gone through melike thread through a needle.Everything I do is stiched with its color.’

Alice Jolly chronicles the stillbirth of her daughter, subsequent recurrent miscarriages, failed IVFs, the attempts to deal with the mess that is the adoption process in the UK, with great beauty and insight. I imagined it might be too tragic to read, but it is written with such compassion, and sometimes humour, that it is compulsive. Yes, sometimes I cried, but often I smiled. The overwhelming message of the book is Hope, both the abstract emotion and the small, blonde girl whose name it is. Alice and her husband eventually went to America where surrogacy is both legal and regulated. Hope’s birth certificate has three names on it; that of the woman who carried her, the woman who donated the egg and Alice herself. The process was not easily entered into and there was a great deal of legal (and personal) searching by both Alice and her husband before Hope became their daughter. It probably helped that Alice’s husband, Stephen, is an international lawyer because they were breaking new ground when they brought Hope back to England. Not until Hope was several months old, and a High Court judge signed off the papers, could Alice and Stephen really be sure that she was legally and absolutely theirs.

Alice is interesting on the subject of memoir; “Although I’m a writer by profession, I have always felt sure that I would never write a memoir. I do not trust them, never have. Me-me-me, moi-moi-moi.” Alice has already written two very accomplished novels published by Simon and Schuster, but distrusts the techniques of fiction in the service of truth. “When you write a novel you work with chains of cause and effect, moments of resolution where meaning might briefly and brilliantly dazzle through. Will it be the same if I write a memoir?” But she has written more than a memoir. It is a blazing, courageous analysis of motherhood and (almost as an aside) daughterhood. Alice spares herself nothing. Another of her quotes is from Nietzsche: ‘We have art in order not to die of the truth’.

It is obvious why this book won the PEN Ackerley award – there is nothing else like it. Which was one of the reasons why her agent (who was also mine) and mainstream publishing in general were too nervous to take it on. Dead Babies and Seaside Towns was crowd-funded through Unbound, which had Paul Kingsnorth's prize-winning, Man Booker listed The Wake last year. It seems clear that Big Publishing had better get its act together when it comes to new directions in contemporary literature or it will find when it eventually gets to the harbour that the tide has gone out and the boat has long gone.

Alice Jolly is crowd-funding her 3rd novel 'Between the Regions of Kindness' which you subscribe to via Unbound by clicking here. I've read the manuscript and, believe me, it's brilliant!

Published on July 17, 2016 09:47

July 12, 2016

Tuesday Poem: Serena Williams reads Maya Angelou 'And Still I Rise'

On the big, emotional occasions it seems that only poetry can properly express how we feel. Weddings, funerals, births, love affairs, despair and disaster all merit a verse or two - even team sports find a rousing chant useful to get the adrenaline flowing. People who might never read a volume of poetry themselves will trawl the internet and find one particular poem that says exactly the emotions they can’t express. Or they might write one, discovering a creativity they didn’t know they had. So it was particularly wonderful to hear Serena Williams, one of the greatest athletes in sport today (perhaps ever), read a moving and highly political poem by Maya Angelou, when she won the Wimbledon singles championship for the 7th time (and the doubles for the sixth) at the age of 35. It’s a very beautiful poem, and particularly relevant for everything that is going on in the USA at the present time.

On the big, emotional occasions it seems that only poetry can properly express how we feel. Weddings, funerals, births, love affairs, despair and disaster all merit a verse or two - even team sports find a rousing chant useful to get the adrenaline flowing. People who might never read a volume of poetry themselves will trawl the internet and find one particular poem that says exactly the emotions they can’t express. Or they might write one, discovering a creativity they didn’t know they had. So it was particularly wonderful to hear Serena Williams, one of the greatest athletes in sport today (perhaps ever), read a moving and highly political poem by Maya Angelou, when she won the Wimbledon singles championship for the 7th time (and the doubles for the sixth) at the age of 35. It’s a very beautiful poem, and particularly relevant for everything that is going on in the USA at the present time.You may write me down in history

With your bitter, twisted lies,

You may tread me in the very dirt

But still, like dust, I'll rise.

Does my sassiness upset you?

Why are you beset with gloom?

'Cause I walk like I've got oil wells

Pumping in my living room.

Just like moons and like suns,

With the certainty of tides,

Just like hopes springing high,

Still I'll rise.

Did you want to see me broken?

Bowed head and lowered eyes?

Shoulders falling down like teardrops.

Weakened by my soulful cries.

Does my haughtiness offend you?

Don't you take it awful hard

'Cause I laugh like I've got gold mines

Diggin' in my own back yard.

You may shoot me with your words,

You may cut me with your eyes,

You may kill me with your hatefulness,

But still, like air, I'll rise.

Does my sexiness upset you?

Does it come as a surprise

That I dance like I've got diamonds

At the meeting of my thighs?

Out of the huts of history's shame

I rise

Up from a past that's rooted in pain

I rise

I'm a black ocean, leaping and wide,

Welling and swelling I bear in the tide.

Leaving behind nights of terror and fear

I rise

Into a daybreak that's wondrously clear

I rise

Bringing the gifts that my ancestors gave,

I am the dream and the hope of the slave.

I rise

I rise

I rise.

© Maya Angelou

And Still I Rise, 1978, Random House USA

Want to hear Serena Williams read it?

Published on July 12, 2016 14:18